Abstract

Background:

The Multiple Source Method (MSM) and the National Cancer Institute Method (NCI) are methods that estimate usual dietary intake from short-term dietary assessment instruments, such as 24-hour recalls (24HR). Their performance varies according to sample size and nutrients distribution. A comparison of these methods among a multi-ethnic youth population, for which nutrient composition and dietary variability may differ from adults, is a gap in the literature.

Objective:

To compare the performance of the NCI method relative to MSM in estimating usual dietary intakes in Hispanic/Latino adolescents.

Design:

Data derived from the cross-sectional population-based Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latino Youth (HCHS/SOL Youth), an ancillary study of offspring of participants in the adult HCHS/SOL cohort. Dietary data were obtained by two 24HR.

Participants/setting:

1,453 Hispanic/Latino youth (8–16y) living in 4 urban US communities (Bronx-NY, Chicago-IL, Miami-FL, San Diego-CA) in 2012–2014.

Main outcome measures:

The NCI method and the MSM were applied to estimate usual intake of total energy, macronutrients, minerals and vitamins, added sugar, and caffeine.

Statistical analyses:

Mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, coefficient of variation, variance ratio, and differences between NCI and MSM methods and the two-day-mean were estimated in several percentiles of the distribution, as well as concordance correlation coefficients and Bland-Altman plot analysis.

Results:

The distributions of all nutrients studied were very similar between NCI and MSM. The correlation between NCI and MSM was >0.80 for all nutrients (p<0.001), except dietary cholesterol, vitamin C and omega-3 fatty acids. In individual estimations, NCI method predicted higher estimates and lower variance than the MSM. The lowest level of agreement was observed in the values at the tails of the distribution, and for nutrients with high variance ratio.

Conclusions:

Overall, both MSM and NCI method provided acceptable estimates of the usual intake distribution using 24HR, and they better represented the usual intake compared with two-day mean, correcting for intra-individual variability.

Keywords: Diet, usual intake, 24-hour dietary recall, Multiple Source Method, National Cancer Institute method

Introduction

In nutritional epidemiology, the usual dietary intake of individuals, represented by the long-term average of daily intake, is the exposure of interest when the relationship between diet and chronic diseases is investigated1,2.

Short-term dietary assessment methods, such as dietary records and 24-hour recalls (24HR), describe the actual intake of individuals, and they provide rich detail about the types and amounts of foods, beverages and meals consumed, allowing considerable flexibility for data analysis1. They also capture cultural nuances of the diet (such as traditional ingredients, brands and cooking methods), making assessment applicable for studies with multi-ethnic populations3. However, a single dietary assessment day leads to a poor approximation of the usual intake, owing to the day-to-day variation of the human diet4.

If a sufficient number of days is collected per individual, the average intake can be a good estimate of usual intake1, but, for practical reasons, such as the time spent, cost, and high respondent burden, collection of multiple days of intake may be infeasible in most epidemiological studies. To overcome this challenge, different statistical methodologies have been proposed for estimating usual intake distributions using a few repeated short-term measurements2,5–13. Their rationale is to handle skewed data and to estimate and remove the day-to-day variation of intake, also called within-person variation14. Despite the common framework, the methods may differ in relation to the numerical methods used, differences in underlying assumptions regarding the measurement characteristics, statistical complexity, and software implementation14,15.

The Multiple Source Method (MSM) and the National Cancer Institute method (NCI method), for example, share the assumption that the short-term measurement obtained by the 24HR provides unbiased measurements for usual intake14,16 and they link the probability to consume with the amount of consumption12,16. The methods also share similar steps to assess usual intake distributions of nutrients and foods (including those episodically consumed) if at least two repeated measurements for some participants are provided. For these, they estimate the probability of intake and the amount of consumption and combine both estimations. In addition, both methods allow for adjustment of covariates in the modeling, including food propensity questionnaire (FPQ) information to improve the power to detect relationships between dietary intakes as predictor variables and other variables particularly for episodically consumed foods10,17. On the other hand, they differ in terms of modeling procedures: in the NCI method, the usual intake distribution is estimated based on parameters defined in the model, such as within- and between-person variance, the power of Box-Cox transformation and population mean; while in MSM, parameters of the usual intake distribution are calculated directly from the estimated distribution of individual’s usual intake18. While the MSM estimates the population’s usual intake distribution by providing first estimates of individual usual intakes, the NCI method estimates first the population usual intake and thereafter the individual’s usual intake17. They also differ in terms of handling non-consumers, inclusion of external information on the proportion of non-consumers, coping with correlations, allowing the use of survey weights, and platforms for users to run the models17.

Although the performance of these methods has been investigated by previous studies10,15,17–19, the findings varied according to the sample size and the distribution of the food groups or nutrients of interest, leading to different conclusions. In general, the estimation bias is larger when there is low frequency of consumption, large between-day variance, highly skewed distribution, and small sample sizes17,19. For example, in simulated scenarios of daily-consumed nutrients with a Box-Cox distribution and small sample sizes, the MSM achieved more accurate estimates than the NCI method, particularly for the 10th and 90th percentiles15.

In this context, this study aimed to compare the performance of the NCI method20 with the performance of the MSM16 for estimating the usual energy and nutrient intakes among Hispanic/Latino adolescents. To our knowledge, a comparison of methods for usual intake estimation among a multi-ethnic child and adolescent population, for which nutrient composition and dietary variability may differ from adults, has not been previously reported in the literature.

Methods

This study analyzed dietary data from the Hispanic Community Children’s Health Study/Study of Latino Youth (SOL Youth), an ancillary study with the offspring of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL), the largest population-based cohort study of Hispanic/Latino adults living in four regions of the United States: Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; Bronx, NY; and San Diego, CA. HCHS/SOL recruited 16,415 adults (18–74 yr) between 2008–2011 of self-identified Hispanic/Latino heritage using a probability sample design21,22. Children aged 8 to 16 years living with at least one parent or legal guardian who participated in HCHS/SOL were invited to participate in SOL Youth. The SOL Youth aimed to investigate the influence of youth acculturation and parent-child differences in acculturation; the influence of youth’s psychosocial functioning; and the associations of parenting strategies, family behaviors and parent lifestyle behaviors on youth’s lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic risk profiles. SOL Youth data collection occurred between 2012–2014 and obtained data from 1,466 participants.

Socioeconomic and demographic data as well as clinic examination were obtained during a baseline visit to one of the field centers. Details about the methodology and protocol of SOL Youth have been published elsewhere23,24. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, with approval from the institutional review boards of each of the institutions involved in the study. Written informed consent and assent were obtained from parent/caregivers and their children, respectively.

Dietary Intake Assessment

Dietary intake was assessed from each child/adolescent, with parental assistance if needed, by two non-consecutive 24-hour dietary recalls (24HR). The first 24HR was administered in-person by a trained interviewer at the field center and the second 24HR was mostly telephone administered (some of them were administered in-person) with a time-interval ranging from five to 45 days after the first collection and following the initial examination interview. Both 24HR were collected using the software Nutrition Data System for Research25, which uses the multi-pass method and contains over 18,000 foods, 8,000 brand name products, many ethnic foods, supplements and vitamins. Participants were instructed to describe the food intake as detailed as possible, including eating occasions, meal time, cooking methods, seasonings and brand names. Food models and amounts booklet were provided for aiding the estimation of portion sizes in the first and second 24HR, respectively. The participants were also asked about the intake amounts reported in the 24HR, indicating if the amount consumed was considered more, same, or less than the usual amount consumed.

For analysis, recalls that were deemed unreliable by the interviewer (n=106) or whose energy intake reported was below the 1st or above the 99th percentile by sex (n=55) were excluded. Data cleaning was done separately for each dietary recall, since intake from the first 24HR tends to be higher than intake from the second recall26,27. Thus, from among the 1,466 children and adolescents in SOL Youth with dietary information, the final analytical sample for the current study consisted of 1,453 children and adolescents, of which 90% (n=1,304) had both 24HR and 10% (n=149) had only one 24HR.

Statistical Analysis

The NCI method20 and the MSM16 were used to estimate the usual intake of total energy, macronutrients (total carbohydrate, protein, and total fat, in grams), omega-3 fatty acids (i.e., eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DHA), mg), dietary cholesterol (mg), minerals (calcium, iron, and potassium, in mg), vitamins (A, B12, C, and D), added sugar (g), and caffeine (mg). These nutrients were chosen for analysis because they present different distributions and scales, and are frequently assessed 28–31. Moreover, because some of these nutrients are consumed at sub-optimal levels, they are considered to be of high public health concern. These include vitamin D for which almost 100% of children and adolescents in U.S.A. showed inadequate intake)29, or added sugar, for which 88% of adolescents presented intake above recommendation32. For comparison, the two-day mean of the 24HR was calculated for each dietary component. When the participant did not have two days of intake, the value of one day was used.

In the NCI method, the usual energy and nutrient intakes were estimated through MIXTRAN, DISTRIB and INDIVINT macros, version 2.1, for a single dietary component in the SAS software33. In brief, the MIXTRAN macro fits a nonlinear mixed effects model to obtain parameter estimates and allows for adjusting for covariates; while DISTRIB macro uses parameter estimates from MIXTRAN and a Monte Carlo method to estimate the distribution of usual intake for a food or nutrient, and INDIVINT macro uses parameter estimates from MIXTRAN to predict individual food or nutrient intake for use in a disease model. For most dietary components evaluated, only the amount model was run (one-part model), because the probability of consumption for these components is assumed to be equal to one. As recommended, the zero intake values were replaced with one-half the minimum amount consumed before running the amount-only model34. For omega-3 fatty acids and caffeine, which presented higher percentage of zero intake, the two-part nonlinear mixed effects measurement error model with correlated random effects, used for episodically consumed dietary components, were performed in all the macros. The macros and further details about the NCI method are available at http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/.

The MSM was accessed online at http://msm.dife.de to perform the analyses. As in the NCI analysis, it was assumed a probability of consumption equal to one (i.e., by assuming that all adolescents were habitual consumers) for all nutrients evaluated. For both methods, covariates in the usual intake models included age (in years), sex (female/male), day of the week of dietary recall weekend/weekday), self-perception about intake amounts (more, same, or less than usual amount), and interview sequence of the dietary recall (first 24HR or second 24HR).

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation of the mean, minimum and maximum values, coefficient of variation (CV), variance ratio (VR), as well as percentile distribution were calculated for the NCI DISTRIB macro, MSM, and the two-day-mean estimates. Concordance correlation coefficients (CCC) proposed by Lin35 were also calculated to evaluate the agreement between NCI INDIVINT macro and MSM estimates. The CCC estimate the agreement between variables measured by two different methods on a continuous scale36. The CCC evaluate both measures of precision and accuracy of the methods37. Additionally, the Bland-Altman plot analysis38 was conducted to graphically depict the agreement between estimates from NCI INDIVINT macro and MSM methods. By Bland-Altman plot analysis, the difference of the two paired measurements (i.e., NCI – MSM estimate) is plotted against the average of the measurements. Limits of agreement between measures were also constructed within which 95% of the differences between measurements are included39.

Results

The mean age of the analyzed sample was 11.9 years (SD=2.5) and 50.6% were girls. The percent of households with income ≤ $20,000 per year was 52.8%, and 38.5% of the parents had an education level < high school, while 33% had > high school. Forty-nine percent of the children were overweight or obese, according to the 2000 CDC Growth Charts40 (data not shown).

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of usual intake distributions of total energy, macronutrients, added sugar, and caffeine from MSM and NCI method (DISTRIB macro) as well as the distribution of energy and the same components from the two-day average intake; and Table 2 presents these estimates for selected micronutrients. In general, the percentiles estimated using NCI DISTRIB macro produced the largest estimates of mean and median values and the lowest estimates for standard deviations (except for omega-3 mean, which was lower than two-day average intake, but higher than MSM). Mainly, at values until the median (i.e., 50th percentile), both MSM and NCI method produced estimates higher than those obtained from two-day average intake and values lower than those obtained from two-day average intake for percentiles above the median, indicating a narrowing of the tails of the distribution toward the mean with the MSM or NCI method. There are some exceptions, for omega-3 fatty acids, percentiles for both MSM and NCI distributions were higher than two-day average intake until the 75th percentile. The same occur for caffeine and vitamin A only for NCI method.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics of usual intake distributions of total energy, macronutrients, added sugar, and caffeine from Multiple Source Method (MSM) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) method as well as the two-day average intake among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014 (n=1,453).

| Nutrient | Mean | SDa | CV%b | VRc | Mind | Pct 1e | Pct 5e | Pct 10e | Pct 25e | Pct 50e | Pct 75e | Pct 90e | Pct 95e | Pct 99e | Maxf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy, kcal | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 1657.1 | 513.4 | 31.0 | 2.60 | 478.2 | 685.3 | 919.8 | 1042.2 | 1290.8 | 1600.2 | 1985.6 | 2328.2 | 2563.9 | 3015.7 | 3716.5 |

| MSM | 1658.2 | 368.9 | 22.2 | - | 773.6 | 912.8 | 1112.6 | 1207.8 | 1392.9 | 1621.2 | 1891.1 | 2138.9 | 2327.0 | 2622.1 | 3077.0 |

| NCI | 1718.8 | 273.2 | 15.9 | - | 529.9 | 963.8 | 1145.8 | 1254.6 | 1450.2 | 1689.7 | 1965.0 | 2220.2 | 2387.2 | 2729.8 | 4019.4 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 1.1 | 156.7 | - | - | 295.4 | 227.4 | 192.9 | 165.6 | 102.1 | 21.0 | −94.4 | −189.3 | −236.9 | −393.5 | −639.5 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 33.1 | 285.2 | - | - | 51.7 | 278.5 | 226.0 | 212.4 | 159.4 | 89.5 | −20.5 | −108.0 | −176.8 | −285.9 | 303.0 |

| NCI minus MSM | 32.0 | 138.3 | - | - | -243.8 | 51.1 | 33.1 | 46.8 | 57.3 | 68.5 | 73.9 | 81.3 | 60.1 | 107.7 | 942.4 |

| Total Carbohydrate, g | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 220.2 | 73.0 | 33.2 | 2.73 | 33.3 | 82.9 | 113.9 | 135.2 | 169.3 | 211.4 | 262.2 | 319.2 | 354.2 | 422.5 | 509.5 |

| MSM | 220.4 | 50.7 | 23.0 | - | 81.7 | 121.5 | 143.9 | 159.2 | 185.4 | 215.2 | 250.6 | 287.3 | 312.9 | 358.1 | 413.7 |

| NCI | 227.6 | 35.4 | 15.6 | - | 65.6 | 125.1 | 150.1 | 164.9 | 191.7 | 224.0 | 259.8 | 294.7 | 316.7 | 361.5 | 541.9 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.2 | 23.8 | - | - | 48.4 | 38.6 | 29.9 | 24.0 | 16.1 | 3.8 | −11.6 | −31.8 | −41.3 | −64.5 | −95.9 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 4.1 | 43.0 | - | - | 32.3 | 42.3 | 36.2 | 29.7 | 22.3 | 12.6 | −2.4 | −24.4 | −37.6 | −61.0 | 32.4 |

| NCI minus MSM | 3.9 | 20.6 | - | - | -16.0 | 3.6 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 128.2 |

| Total Protein, g | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 66.3 | 23.4 | 35.3 | 3.34 | 8.6 | 23.8 | 33.3 | 39.3 | 50.4 | 63.1 | 79.2 | 97.7 | 108.5 | 136.9 | 184.6 |

| MSM | 66.4 | 15.2 | 22.9 | - | 26.1 | 37.1 | 44.0 | 48.3 | 56.0 | 64.7 | 75.6 | 86.8 | 93.0 | 108.5 | 136.1 |

| NCI | 68.3 | 11.0 | 16.1 | - | 19.8 | 37.1 | 44.6 | 49.1 | 57.2 | 67.2 | 78.1 | 88.8 | 95.6 | 109.4 | 166.8 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.1 | 9.0 | - | - | 17.5 | 13.2 | 10.7 | 9.0 | 5.6 | 1.6 | −3.6 | −10.9 | −15.5 | −28.3 | −48.6 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 1.2 | 14.9 | - | - | 11.2 | 13.3 | 11.3 | 9.8 | 6.8 | 4.1 | −1.1 | −8.9 | −12.9 | −27.5 | −17.8 |

| NCI minus MSM | 1.2 | 6.4 | - | - | -6.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 30.8 |

| Total Fat, g | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 58.8 | 23.6 | 40.0 | 3.92 | 3.0 | 16.1 | 24.8 | 31.6 | 42.0 | 55.9 | 72.1 | 89.6 | 102.2 | 128.3 | 158.7 |

| MSM | 58.9 | 15.4 | 26.1 | - | 18.4 | 28.3 | 36.0 | 40.4 | 48.1 | 57.6 | 68.2 | 79.1 | 85.3 | 103.9 | 118.1 |

| NCI | 61.5 | 10.7 | 17.4 | - | 15.2 | 30.9 | 38.1 | 42.4 | 50.4 | 60.1 | 71.2 | 82.5 | 89.7 | 104.7 | 160.3 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.1 | 8.9 | - | - | 15.4 | 12.3 | 11.2 | 8.8 | 6.1 | 1.6 | −3.9 | −10.6 | −16.9 | −24.4 | −40.6 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 1.7 | 15.0 | - | - | 12.2 | 14.8 | 13.3 | 10.7 | 8.4 | 4.1 | −0.9 | −7.1 | −12.5 | −23.6 | 1.6 |

| NCI minus MSM | 1.6 | 6.7 | - | - | -3.2 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 42.2 |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 67.1 | 136.6 | 203.5 | 7.44 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 15.5 | 35.0 | 62.5 | 125.0 | 240.5 | 676.5 | 1837.0 |

| MSM | 59.9 | 44.0 | 73.5 | - | 2.8 | 15.6 | 22.9 | 27.0 | 35.6 | 49.7 | 68.4 | 99.7 | 132.2 | 225.4 | 568.9 |

| NCI | 64.1 | 36.9 | 57.6 | - | 4.6 | 14.9 | 22.2 | 27.2 | 38.4 | 55.7 | 80.2 | 111.0 | 133.8 | 190.9 | 641.6 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | -7.2 | 99.9 | - | - | 2.8 | 15.6 | 20.4 | 21.5 | 20.1 | 14.7 | 5.9 | -25.3 | -108.3 | -451.1 | -1268.1 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | −3.0 | −99.7 | - | - | 4.6 | 14.9 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 22.9 | 20.7 | 17.7 | −14.0 | −106.7 | −485.6 | −1195.4 |

| NCI minus MSM | 4.2 | -7.1 | - | - | 1.8 | -0.7 | -0.7 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 6 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 1.6 | -34.5 | 72.7 |

| Dietary Cholesterol, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 215.8 | 134.4 | 62.3 | 5.81 | 0.0 | 37.1 | 68.6 | 82.6 | 121.7 | 180.9 | 278.3 | 398.3 | 472.2 | 656.0 | 1114.5 |

| MSM | 216.4 | 72.9 | 33.7 | - | 49.3 | 92.2 | 119.0 | 134.8 | 162.9 | 203.8 | 256.4 | 315.6 | 354.1 | 418.4 | 614.7 |

| NCI | 223.8 | 43.4 | 19.4 | - | 39.7 | 95.5 | 122.9 | 140.1 | 172.9 | 215.4 | 265.7 | 317.9 | 352.4 | 425.8 | 783.1 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.5 | 68.2 | - | - | 49.3 | 55.1 | 50.3 | 52.2 | 41.2 | 22.9 | −21.9 | −82.8 | −118.1 | −237.6 | −499.9 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 5.4 | 102.3 | - | - | 39.7 | 58.5 | 54.3 | 57.4 | 51.2 | 34.5 | −12.6 | −80.4 | −119.7 | −230.2 | −331.5 |

| NCI minus MSM | 4.8 | 39.8 | - | - | -9.6 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 9.3 | 2.4 | -1.7 | 7.4 | 168.4 |

| Added Sugar, g | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 63.8 | 38.2 | 59.9 | 3.07 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 12.4 | 22.2 | 38.0 | 56.9 | 82.7 | 111.3 | 135.3 | 191.0 | 321.0 |

| MSM | 63.8 | 25.8 | 40.4 | - | 1.9 | 17.3 | 26.4 | 34.2 | 46.1 | 60.8 | 78.3 | 96.8 | 110.9 | 143.6 | 210.8 |

| NCI | 66.7 | 17.7 | 26.6 | - | 3.8 | 20.3 | 30.0 | 36.0 | 47.9 | 63.6 | 82.2 | 101.6 | 114.1 | 140.8 | 251.9 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.0 | 13.9 | - | - | 1.9 | 14.8 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 8.2 | 3.8 | −4.4 | −14.5 | −24.4 | −47.4 | −110.3 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 1.5 | 23.0 | - | - | 3.8 | 17.9 | 17.5 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 6.6 | −0.5 | −9.7 | −21.2 | −50.2 | −69.2 |

| NCI minus MSM | 1.5 | 10.3 | - | - | 1.9 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 3.2 | -2.8 | 41.1 |

| Caffeine, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 18.0 | 29.3 | 162.8 | 1.95 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 6.8 | 22.8 | 49.3 | 71.0 | 141.3 | 314.6 |

| MSM | 17.7 | 17.2 | 97.3 | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 6.6 | 12.1 | 22.2 | 39.0 | 49.9 | 83.5 | 172.6 |

| NCI | 19.2 | 16.1 | 84.6 | - | 0.12 | 1.45 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 8.2 | 14.7 | 25.2 | 39.2 | 50.2 | 78.5 | 252.8 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | −0.3 | 13.3 | - | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 5.4 | −0.6 | −10.3 | −21.0 | −57.8 | −142.1 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 1.2 | −13.2 | - | - | 0.12 | 1.45 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 2.4 | −10.1 | −20.8 | −62.8 | −61.8 |

| NCI minus MSM | 1.5 | -1.1 | - | - | 0.12 | 1.45 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | -5 | 80.2 |

SD = Standard Deviation

CV% = Coefficient of Variation

VR = Variance Ratio (within-to-between-person variance)

Min = Minimum

Pct = Percentile

Max = Maximum

Table 2:

Descriptive statistics of usual intake distributions of selected micronutrients from Multiple Source Method (MSM) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) method as well as the two-day average intake among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014 (n=1,453).

| Nutrient | Mean | SDa | CV%b | VRc | MInd | Pct 1e | Pct 5e | Pct 10e | Pct 25e | Pct 50e | Pct 75e | Pct 90e | Pct 95e | Pct 99e | Maxf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 1936.8 | 721.0 | 37.2 | 2.29 | 291.2 | 645.5 | 924.0 | 1098.5 | 1447.6 | 1840.6 | 2345.1 | 2879.8 | 3212.8 | 4027.4 | 5477.7 |

| MSM | 1938.7 | 503.7 | 26.0 | - | 691.1 | 969.2 | 1206.4 | 1343.9 | 1588.0 | 1889.9 | 2233.2 | 2592.5 | 2829.3 | 3299.5 | 4267.6 |

| NCI | 1985.4 | 347.5 | 17.5 | - | 486.5 | 1003.7 | 1238.2 | 1377.9 | 1632.9 | 1946.9 | 2296.7 | 2642.3 | 2858.9 | 3300.4 | 5350.2 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 1.9 | 230.4 | - | - | 400.0 | 323.8 | 282.4 | 245.4 | 140.3 | 49.2 | −112.0 | −287.3 | −383.5 | −727.9 | −1210.1 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 25.1 | 413.8 | - | - | 195.3 | 358.2 | 314.2 | 279.4 | 185.3 | 106.3 | −48.4 | −237.5 | −353.8 | −727.0 | −127.5 |

| NCI minus MSM | 23.2 | 195.1 | - | - | −204.7 | 34.5 | 31.8 | 34.0 | 45.0 | 57.0 | 63.6 | 49.8 | 29.6 | 1.0 | 1082.6 |

| Calcium, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 915.3 | 409.2 | 44.7 | 2.96 | 67.4 | 178.0 | 332.9 | 433.7 | 627.4 | 865.0 | 1157.2 | 1449.2 | 1655.3 | 2113.9 | 2955.9 |

| MSM | 916.7 | 273.5 | 29.8 | - | 288.9 | 378.8 | 504.2 | 587.2 | 721.2 | 890.7 | 1089.9 | 1271.9 | 1383.7 | 1661.4 | 2073.2 |

| NCI | 935.8 | 181.6 | 19.4 | - | 168.4 | 414.0 | 535.7 | 608.9 | 743.4 | 912.4 | 1103.4 | 1293.4 | 1414.6 | 1659.8 | 2733.4 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 1.4 | 144.8 | - | - | 221.5 | 200.8 | 171.3 | 153.5 | 93.8 | 25.8 | −67.2 | −177.3 | −271.6 | −452.6 | −882.7 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 12.1 | 247.3 | - | - | 101.0 | 236.0 | 202.7 | 175.3 | 116.0 | 47.4 | −53.8 | −155.9 | −240.7 | −454.1 | −222.5 |

| NCI minus MSM | 10.7 | 110.2 | - | - | -120.5 | 35.2 | 31.5 | 21.7 | 22.2 | 21.7 | 13.4 | 21.4 | 30.9 | -1.5 | 660.2 |

| Iron, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 13.6 | 6.1 | 44.6 | 3.75 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 9.4 | 12.4 | 16.6 | 20.9 | 25.0 | 35.5 | 44.8 |

| MSM | 13.6 | 3.7 | 27.5 | - | 5.3 | 6.9 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 15.8 | 18.4 | 20.7 | 24.8 | 29.2 |

| NCI | 13.9 | 2.3 | 16.8 | - | 3.9 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 13.5 | 16.1 | 18.6 | 20.3 | 23.9 | 44.3 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.0 | 2.6 | - | - | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.6 | −0.8 | −2.5 | −4.3 | −10.7 | −15.6 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 0.2 | 4.2 | - | - | 1.4 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.1 | −0.6 | −2.3 | −4.6 | −11.6 | −0.6 |

| NCI minus MSM | 0.1 | 1.8 | - | - | −1.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.4 | −0.9 | 15.1 |

| Vitamin D (calciferol), mcg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 6.2 | 3.6 | 58.0 | 2.73 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 8.2 | 10.8 | 12.6 | 17.0 | 29.0 |

| MSM | 6.2 | 2.4 | 38.2 | - | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 12.9 | 19.6 |

| NCI | 6.2 | 1.6 | 25.5 | - | 0.3 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 12.6 | 22.7 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.0 | 1.3 | - | - | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −1.5 | −2.2 | −4.1 | −9.4 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 0.0 | 2.2 | - | - | 0.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −1.5 | −2.2 | −4.4 | −6.3 |

| NCI minus MSM | 0.0 | 0.9 | - | - | −0.5 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 3.1 |

| Total Vitamin A Activity (RAE), mcg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 589.2 | 409.9 | 69.6 | 2.08 | 4.3 | 67.8 | 171.6 | 237.8 | 345.0 | 514.7 | 718.2 | 1012.7 | 1239.8 | 1778.7 | 8047.5 |

| MSM | 589.1 | 240.6 | 40.8 | - | 133.9 | 196.4 | 283.4 | 340.1 | 431.0 | 556.4 | 691.5 | 870.5 | 1007.6 | 1301.3 | 3716.2 |

| NCI | 600.7 | 142.3 | 23.7 | - | 71.1 | 216.1 | 297.3 | 348.5 | 446.3 | 574.5 | 727.6 | 886.1 | 992.1 | 1211.5 | 2303.0 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | -0.1 | 189.9 | - | - | 129.6 | 128.6 | 111.8 | 102.2 | 86.0 | 41.6 | -26.6 | -142.2 | -232.2 | -477.4 | -4331.3 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 5.0 | 294.1 | - | - | 66.8 | 148.4 | 125.7 | 110.6 | 101.3 | 59.8 | 9.4 | −126.6 | −247.7 | −567.2 | −5744.5 |

| NCI minus MSM | 5.2 | 116.0 | - | - | −62.9 | 19.8 | 13.9 | 8.4 | 15.3 | 18.1 | 36.1 | 15.6 | −15.5 | −89.8 | −1413.2 |

| Total Vitamin C, mg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 77.3 | 61.8 | 79.9 | 3.59 | 0.1 | 4.8 | 12.5 | 18.1 | 33.2 | 62.7 | 104.4 | 151.2 | 192.6 | 292.4 | 563.3 |

| MSM | 78.0 | 36.0 | 46.2 | - | 12.6 | 24.4 | 33.1 | 39.3 | 51.4 | 71.3 | 96.5 | 125.3 | 143.0 | 197.1 | 303.5 |

| NCI | 80.2 | 19.9 | 24.8 | - | 6.4 | 24.1 | 34.8 | 41.7 | 55.7 | 74.9 | 99.1 | 125.4 | 143.5 | 182.0 | 392.2 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.6 | 28.5 | - | - | 12.5 | 19.6 | 20.6 | 21.2 | 18.2 | 8.6 | −7.9 | −25.9 | −49.6 | −95.4 | −259.8 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 1.7 | 44.9 | - | - | 6.3 | 19.2 | 22.3 | 23.6 | 22.5 | 12.2 | −5.4 | −25.8 | −49.1 | −110.4 | −171.1 |

| NCI minus MSM | 1.0 | 18.5 | - | - | −6.2 | −0.3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | −15.1 | 88.7 |

| Total Vitamin B12, mcg | |||||||||||||||

| Two-day mean | 4.7 | 3.0 | 62.7 | 2.33 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 7.8 | 9.3 | 13.1 | 60.1 |

| MSM | 4.7 | 1.8 | 37.8 | - | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 28.8 |

| NCI | 4.8 | 1.1 | 23.1 | - | 0.6 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 17.1 |

| MSM minus Two-day mean | 0.0 | 1.3 | - | - | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 | −0.3 | −0.9 | −1.6 | −3.5 | −31.3 |

| NCI minus Two-day mean | 0.0 | 2.1 | - | - | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | −0.2 | −0.9 | −1.7 | −3.9 | −43.0 |

| NCI minus MSM | 0.0 | 0.8 | - | - | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.3 | -11.7 |

SD = Standard Deviation

CV% = Coefficient of Variation

VR = Variance Ratio (within-to-between-person variance)

Min = Minimum

Pct = Percentile

Max = Maximum

MSM estimates of mean, percentiles, minimum, and maximum values were similar to NCI estimate of distribution of usual intake. The minimum values of the distribution predicted by NCI method were usually lower than those predicted by MSM (they were higher for omega-3, added sugar, and caffeine, and the same for vitamin B12), and the maximum values of the distribution predicted by NCI were higher than MSM (except for vitamins A and B12). Except for vitamins D and B12 (where the estimated median and mean values were the same), NCI method estimated higher values of the mean and median than MSM.

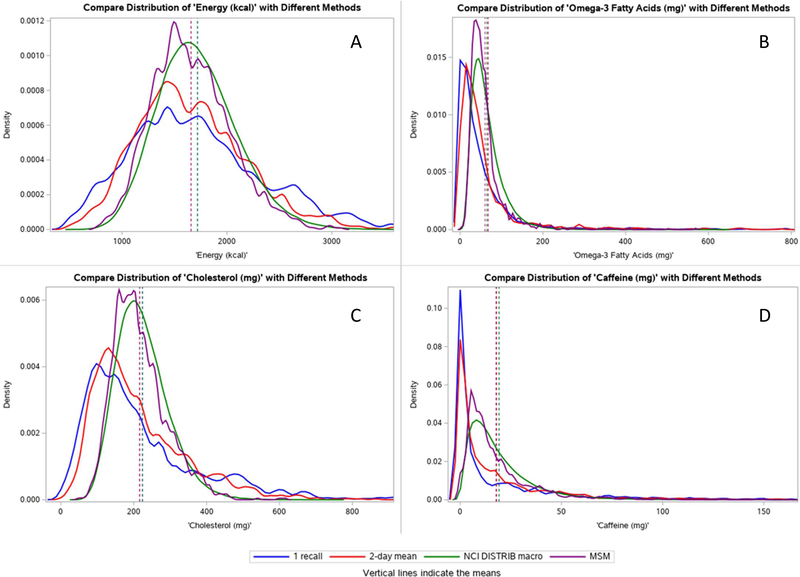

Figure 1 presents the distribution curve of examples of the dietary components (energy, omega-3, cholesterol, and caffeine) using one 24-hour recall, two-day mean, NCI (DISTRIB macro), and MSM. Figure 2 online only presents the distribution for all the evaluated components. The mean values were approximately the same irrespective of the method used and the NCI method and MSM distributions were very similar.

Figure 1:

Usual intake distributions of (A) total energy, (B) omega-3, (C) cholesterol, and (D) caffeine from Multiple Source Method (MSM) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) method (DISTRIB macro) as well as the distribution using one 24HR and the two-day average intake among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014. Usual intake distributions of all the nutrients evaluated are available in Figure 2 online only.

Figure 2 online only:

Usual intake distributions of total energy, macronutrients, added sugar, caffeine, and selected micronutrients from Multiple Source Method (MSM) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) method (DISTRIB macro) as well as the distribution using one 24HR and the two-day average intake among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014.

Regarding the individual predicted values, the concordance correlation coefficient between NCI and MSM was higher than 0.8 for all the components (p<0.001), except for dietary cholesterol (CCC = 0.78; SE = 0.07), vitamin C (CCC = 0.798; SE = 0.04), and omega-3 fatty acids (CCC = 0.59; SE = 0.10) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Concordance correlation coefficient of usual intake of selected nutrients estimated using the Multiple Source Method (MSM), and National Cancer Institute (NCI) method among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014 (n=1,453).

| Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total Energy, kcal | NCI | SEa |

| MSM | 0.905*** | 0.03 |

| Total Carbohydrate, g | ||

| MSM | 0.886*** | 0.04 |

| Total Protein, g | ||

| MSM | 0.881*** | 0.04 |

| Total Fat, g | ||

| MSM | 0.867*** | 0.05 |

| Potassium, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.897*** | 0.03 |

| Calcium, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.886*** | 0.03 |

| Dietary Cholesterol, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.777*** | 0.07 |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.592*** | 0.10 |

| Vitamin D, mcg | ||

| MSM | 0.891*** | 0.03 |

| Vitamin A, mcg | ||

| MSM | 0.827*** | 0.04 |

| Caffeine, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.808*** | 0.06 |

| Added sugar, g | ||

| MSM | 0.890*** | 0.03 |

| Iron, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.824*** | 0.05 |

| Vitamin C, mcg | ||

| MSM | 0.798*** | 0.04 |

| Vitamin B12, mg | ||

| MSM | 0.840*** | 0.04 |

p<0.001

SE = Standard Error

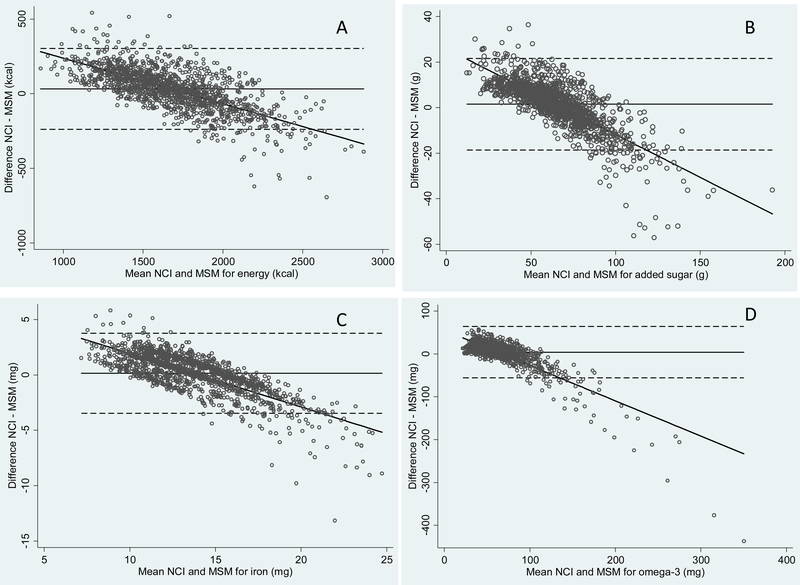

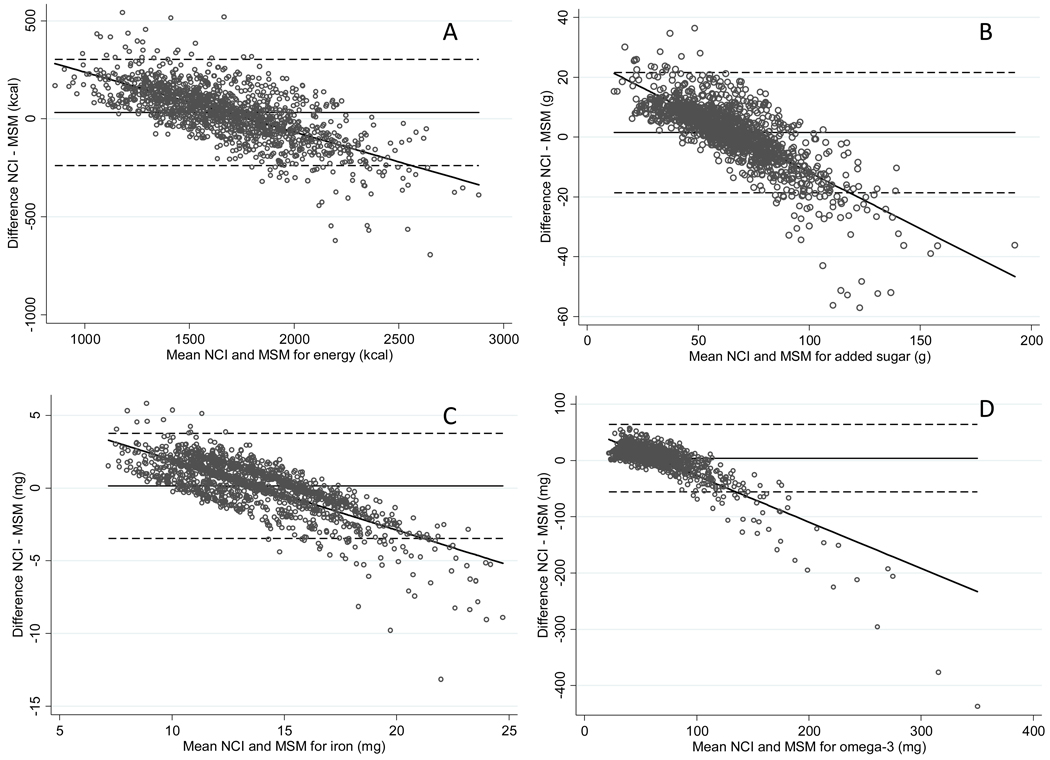

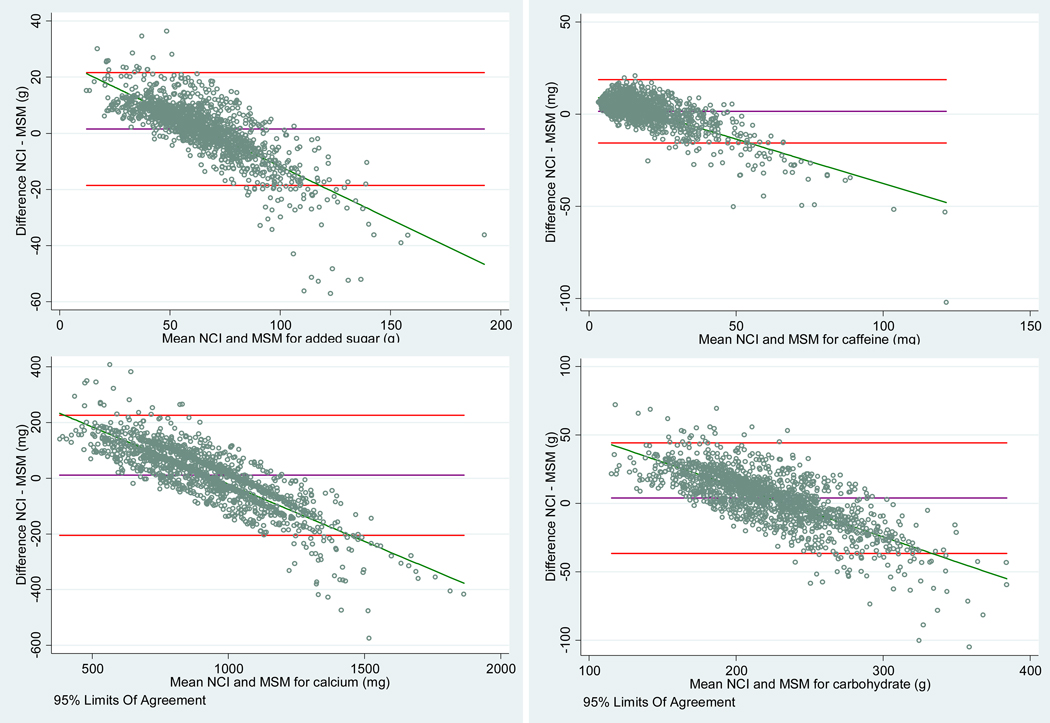

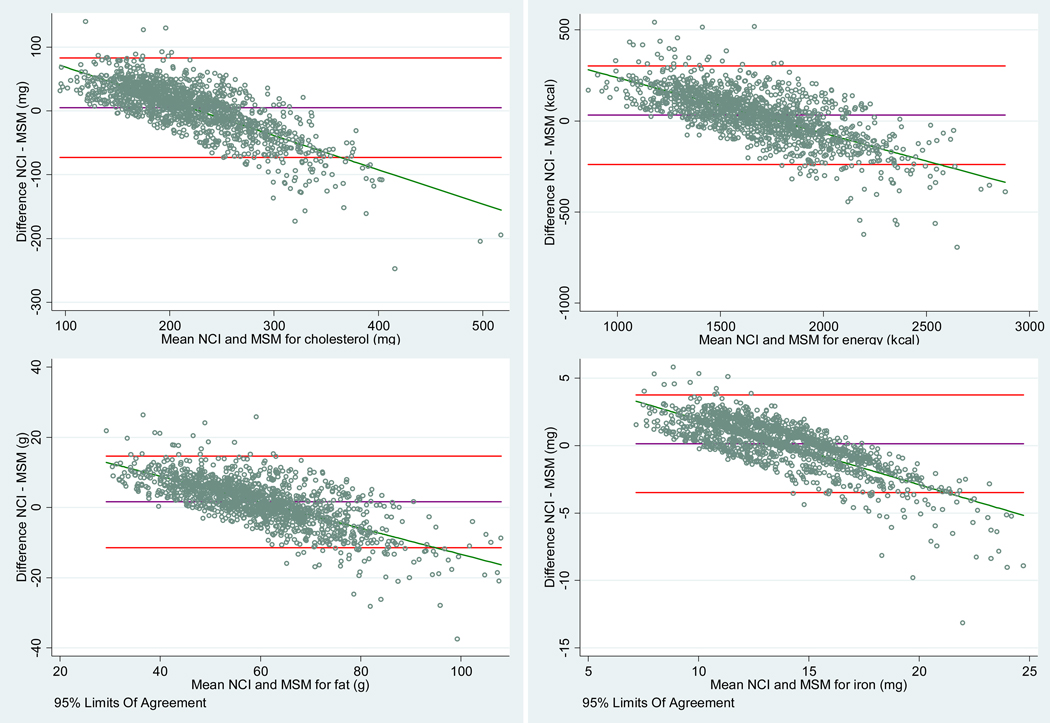

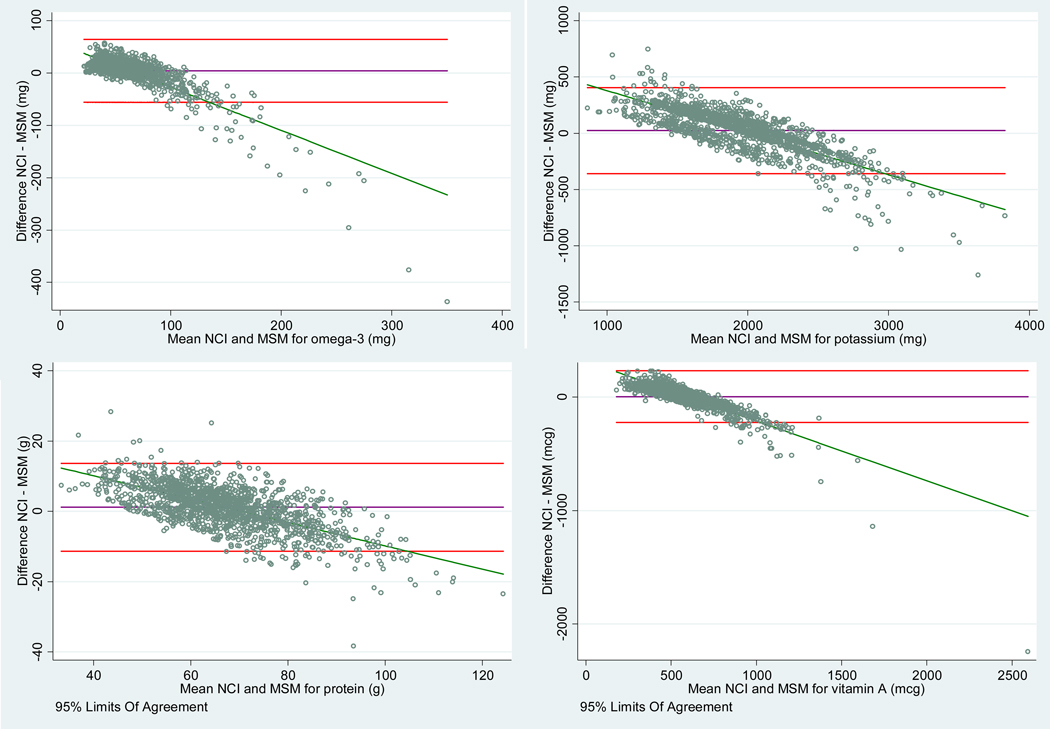

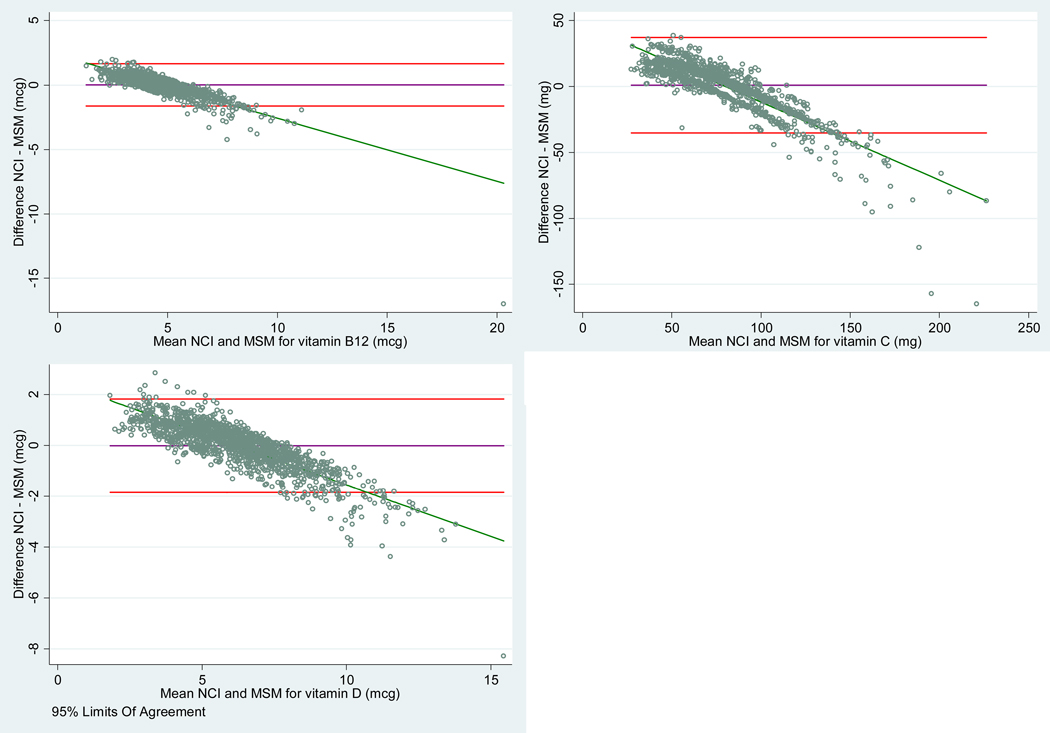

The graphical display of the agreement between individual estimations for four examples energy, added sugar, iron, and omega-3) with MSM and NCI (INDIVINT macro) method is shown in Figure 3. The results for all the dietary components are presented in Figure 4 online only. The Bland-Altman plot presents in the Y axis the difference between the two paired measurements (NCI-MSM) and the X axis presents the average of these measures ((NCI+MSM)/2). The average of the differences was higher than zero for all the components, which means that the first method (NCI) tends to produce higher estimates than the second one (MSM). A negative trend of differences was observed in the plots, indicating that the variance of the data estimated by the NCI (INDIVINT macro) is lower than the variance of the data estimated by the MSM. Moreover, the lowest agreement between the estimations occurred in the extreme values of the distribution.

Figure 3:

Bland-Altman plots comparing the agreement of individual estimates between National Cancer Institute (NCI) method (INDIVINT macro) and MSM method for (A) total energy, (B) added sugar, (C) iron, and (D) omega-3 among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014. The difference between the methods was plotted as NCI method minus MSM. The center solid line represents the mean difference between NCI method and MSM. The upper and lower dashed lines represent the 95% limits of agreement between methods. The inclined thick line represents the regression line to the limits-of-agreement plot fitting the paired differences to the pair-wise means. Bland-Altman plots for all the nutrients evaluated are available in Figure 4 online only.

Figure 4:

Bland-Altman plots comparing the agreement of individual estimates between National Cancer Institute (NCI) method (INDIVINT macro) and MSM method for total energy, macronutrients, added sugar, caffeine, and selected micronutrients among children and adolescents of the SOL-Youth Study 2012–2014. The difference between the methods swas plotted as NCI methosd minus MSM. The center purple line represents the mean difference between NCI method and MSM. The upper and lower red lines represent the 95% limits of agreement between methods. The inclined green line representssssss the regression line to the limits-of-agreement plot fitting the paired differences to the pair-wise means.

Discussion

This study compared two commonly used methods to evaluate usual intake from repeated measurements of 24-hour recalls in a large sample of Hispanic/Latino children and adolescents aged 8 to 16 years living in USA. Overall, the usual intake distribution using MSM and NCI method were similar, but NCI presented lower standard deviation values.

When comparing the mean intake estimated using the two-day mean, the MSM and the NCI method, the values are not expressively different. The similar means occur because the population mean estimated using the MSM and NCI method was designed to be consistent with estimates using a single 24-hour recall per individual16,34. However, when the extreme individual values are compared, the differences become more salient, such as for total fat, added sugar, and vitamin C, in which individual points presented in extreme values in Figure 3 and Figure 4 online only are distant from expected using NCI (INDIVINT macro) versus MSM. When the comparison occurs at the population level, the MSM and NCI (DISTRIB macro) presented similar results, which is useful, for example, to estimate the percentage of the population that have inadequate intake of nutrients.

The NCI method in general narrows the distribution by accounting for the large within-person variability inherent of a short-term instrument like the 24hr dietary recall4,14. A simulation study with samples sizes ranging from 150 to 500 showed that both methods seemed to shrink the intake distributions more than expected, resulting in overestimation of the low percentiles and underestimation of the high percentiles15. Similar results were observed in a simulation study that compared the distribution of usual food intake of 302 individuals with twenty 24HR per individual: both methods overestimated the low percentiles, specifically up to about the 15th and 20th percentile; however, the MSM resulted in higher overestimation of the lower percentiles (percentiles up to 20th30th) followed by a higher underestimation (percentiles 30th to 40th)18. In the present study, in general, the minimum values predicted by NCI method (DISTRIB macro) were lower than those predicted by MSM, and the maximum values were higher, indicating a larger range of the predicted values. However, the lower standard deviation for NCI indicates a narrower curve. Nevertheless, the differences between methods were very subtle, which would not justify choosing one method rather than the other.

One important issue when estimating usual intake arises when reported intake is very low for some nutrients19. In this study, some components presented values of zero for the two-day mean: omega-3 fatty acids (until percentile 1st), caffeine (until percentile 10th), vitamins B12 and D, dietary cholesterol, and added sugars (less than percentile 1st). These zero values could influence the estimated intake distribution by each method. When adolescents were considered habitual consumers, the usual intake for caffeine estimated by the MSM resulted in zero value (until percentile 1st); however for estimation using the NCI method (INDIVINT macro), no zero estimates were predicted for caffeine. When less than 5% of the population had zero intake of a dietary component, the recommendation of the NCI method is to use the amount-only model, replacing the zero intake values with one-half the minimum amount consumed before running the model34, as performed in the present analysis. However, when more than 5% of the population report zero intake of the component (i.e., nonconsumption on a given day), then it is considered episodically consumed41, and the use of the two-part model is indicated42. In the present study, the two-part models were run for omega-3 and caffeine, which presented a better prediction than running the amount model (data not shown). The greatest contributors to caffeine intake in this population were soft drinks with cola, and in smaller proportion, coffee and tea (data not shown). When these foods were not consumed, the intake of caffeine was zero. In the present sample, 20% of the population (n=292) did not consume any food source of caffeine in both 24HR. In the case of nutrients or other components, the compilation of the information from more than one food group may be necessary to account for the food contributors of these components. For MSM, the zero value until 10th percentile of caffeine observed in the two-day mean values does not appear to have significantly compromised the usual intake distribution, and zero values were assigned in the first percentile, even considering all usual consumers in the model, and the NCI method also performed well when running the two-part model, even though no zero values were predicted. Despite the differences in predicting zero values, neither the NCI method nor MSM can be used to identify non-consumers using 24HR information. For this purpose, it is necessary to have additional long-term information from, for example, a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)12,16.

Another important issue to be considered when estimating the usual intake is the variance ratio15. In the present study, omega-3 fatty acids presented a variance ratio of 7.4, and the distribution pattern estimated using MSM was similar to NCI method (NCI predicted the distribution curve slightly shifted to the right); however, the individual estimates presented the lower concordance correlation coefficient of all the dietary components (CCC = 0.592; SE = 0.10)(Table 3). Previous studies have observed that NCI method provided larger bias in intake distribution when the within-person variation was much higher than the between-person variation (e.g., sw2 /sb2=9)15,17,18.

One limitation of this study is that in order to compare the data between both methods, the survey weights of SOL-Youth study could not be used because the MSM does not allow their inclusion. Therefore, in surveys with large sample size and low variance ratio where the differential weighting of individuals and the correlation of individuals within primary sampling units (PSU) and strata must be taken into account, the NCI may be the only option. Another limitation is that the use of FPQ for episodically consumed components, which is not available in the present study, could help MSM to identify non-consumers in the estimation of zero values16. For NCI method, studies indicate a small effect of FPQ information in the correlated model12,17, however the use of the frequency of consumption data adds information when modeling a diet-disease relationship43. Also, the comparison of predicted values with the true usual intake of the population could not be performed due to the lack of a gold standard method.

Important strengths of the study included the evaluation of several dietary components in a large sample of Hispanic/Latino children and adolescents living in the USA. Also, dietary data was collected according to a standardized protocol that minimized as much as possible the bias inherent to the self-reported nature of 24HR. Another strength is that 24HR are better at capturing cultural nuances of diet in ethnically diverse populations such as the one used for this study3.

There is evidence indicating that the usual intake can be estimated using only one replication of the 24HR in a subsample of the study population18,44. Important epidemiological surveys, such as NHANES34, use the NCI as the default method to evaluate usual intake, while other studies, such as The European “Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence” (HELENA)45, use the MSM. Therefore, based on the results of this and previous studies, when choosing which method to use, researchers should consider the sample size, the normality of the distribution, the variance ratio, the access to the method, and whether weights and complex survey design must be included in the appropriate estimation method15,17.

Conclusions

In the present study, both MSM and NCI method provided acceptable estimates of the usual intake distribution using 24HR, and they better represented the usual intake compared with two-day mean, correcting for intra-individual variability. In addition, both provided estimates of individual usual intake, which might be important for epidemiological studies. The smallest agreement was observed in the extremes percentiles of the distribution and for nutrients with high variance ratio. Among this multi-ethnic child and adolescent population, the nutrient composition and dietary variability did not preclude the performance of MSM or NCI method, which performed similarly.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT.

Research Question:

Do the National Cancer Institute method and the Multiple Source Method perform similarly when estimating the usual energy and nutrient intakes among Hispanic/Latino adolescents, for which nutrient composition and dietary variability may differ from adults and other populations?

Key Findings:

MSM estimates of mean, percentiles, minimum, and maximum values were similar to the NCI estimate of distribution of usual intake, with slightly higher values estimated by NCI method. In individual estimations, NCI tends to produce higher estimates and lower variance than the MSM. The lowest agreement between the estimations occurred in the extreme values of the distribution and for nutrients with high variance ratio.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their important contributions.

Funding

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latino Youth was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; Grant K01-HL120951). Youth participants are drawn from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos, which was supported by contracts from the NHLBI to the University of North Carolina (Grant N01HC65233), University of Miami (Grant N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Grant N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (Grant N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (Grant N01-HC65237). The following contribute to this study through a transfer of funds to NHLBI: National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, and the Office of Dietary Supplements. Additional support was provided by São Paulo Research Foundation – FAPESP (J.L.P., grant number 2017/02480–0). The study sponsors did not have any role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jaqueline L. Pereira, Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. CEP: 01246-904..

Michelle A. de Castro, Department of School Feeding Program, Secretariat of Education of São Paulo, Brazil. CEP: 04038-003..

Sandra P. Crispim, Department of Nutrition, Federal University of Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. CEP: 80210-170..

Regina M. Fisberg, Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil..

Carmen R. Isasi, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY. 10461..

Yasmin Mossavar-Rahmani, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY. 10461..

Linda Van Horn, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL. 60611..

Mercedes R. Carnethon, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL. 60611..

Martha L. Daviglus, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL. 60611. Phone: 312-908-7967.

Krista M. Perreira, Department of Social Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. 27599-7240..

Linda C. Gallo, Department of Psychology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA. 92110.

Daniela Sotres-Alvarez, Collaborative Studies Coordinating Center, Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. 27516..

Josiemer Mattei, Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA. 02115..

References

- 1.Willett W Nutritional epidemiology. 3rd edn (Oxford University Press, New York, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusser SM, Carriquiry AL, Dodd KW, Fuller WA. A semiparametric transformation approach to estimating usual daily intake distributions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996; 91: 1440–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subar AF, Freedman LS, Tooze JA, Kirkpatrick SI, Boushey C, Neuhouser ML, et al. Addressing current criticism regarding the value of self-report dietary data. J Nutr. 2015; 145(12): 2639–2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prentice RL, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Huang Y, Van Horn L, Beresford SA, Caan B, et al. Evaluation and comparison of food records, recalls, and frequencies for energy and protein assessment by using recovery biomarkers. Am J Epidem. 2011; 174: 591–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Research Council SiCfDE. Nutrient Adequacy: Assessment Using Food Consumption Surveys. (National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slob W Modeling long-term exposure of the whole population to chemicals in food. Risk Anal. 1993; 13: 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace LA, Duan N, Ziegenfus R. Can long-term exposure distributions be predicted from short-term measurements? Risk Anal. 1994; 14: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck RJ, Hammerstrom KA, Ryan PB. Estimating long-term exposures from short-term measurements. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1995; 5: 359–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann K, Boeing H, Dufour A, Volatier JL, Telman J, Virtanen M, et al. Estimating the distribution of usual dietary intake by short-term measurements. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002; 56: S53–S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haubrock J, Nöthlings U, Volatier JL, Dekkers A, Ocké M, Harttig U, et al. Estimating usual food intake distributions by using the Multiple Source Method in the EPIC-Potsdam Calibration Study. J Nutr. 2011; 141: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slob W Probabilistic dietary exposure assessment taking into account variability in both amount and frequency of consumption. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006; 44: 933–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tooze JA, Midthune D, Dodd KW, Freedman LS, Krebs-Smith SM, Subar AF, et al. A new statistical method for estimating the usual intake of episodically consumed foods with application to their distribution. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106: 1575–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waijers PM, Dekkers AL, Boer JM, Boshuizen HC, van Rossum CT. The potential of AGE MODE, an age-dependent model, to estimate usual intakes and prevalences of inadequate intakes in a population. J Nutr. 2006: 136; 2916–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodd KW, Guenther PM, Freedman LS, Subar AF, Kipnis V, Midthune D, et al. Statistical methods for estimating usual intake of nutrients and foods: a review of the theory. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106: 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laureano GH, Torman VB, Crispim SP, Dekkers A, Camey S. Comparison of the ISU, NCI, MSM, and SPADE methods for estimating usual intake: A simulation study of nutrients consumed daily. Nutrients. 2016; 8: 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartig U, Haubrock J, Knüppel S, Boeing H. The MSM program: web-based statistics package for estimating usual dietary intake using the Multiple Source Method. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011; 65: S87–S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souverein OW, Dekkers AL, Geelen A, Haubrock J, De Vries JH, Ocké MC, et al. Comparing four methods to estimate usual intake distributions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011; 65: S92–S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verly E Jr, Oliveira DC, Fisberg RM, Marchioni DML. Performance of statistical methods to correct food intake distribution: comparison between observed and estimated usual intake. Br J Nutr. 2016; 116: 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goedhart PW, Voet H, Knüppel S, Dekkers AL, Dodd KW, Boeing H, van Klaveren J. A comparison by simulation of different methods to estimate the usual intake distribution for episodically consumed foods. EFSA Support Publ. 2012; 9: 299E. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tooze JA, Kipnis V, Buckman DW, Carroll RJ, Freedman LS, Guenther PM, et al. A mixed-effects model approach for estimating the distribution of usual intake of nutrients: The NCI method. Stat Med. 2010; 29: 2857–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, et al. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010; 20: 642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, et al. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010; 20: 629–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isasi CR, Carnethon MR, Ayala GX, Arredondo E, Bangdiwala SI, Daviglus ML, et al. The Hispanic Community Children’s Health Study/Study of Latino Youth (SOL Youth): design, objectives, and procedures. Ann Epidemiol. 2014; 24: 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayala GX, Carnethon M, Arredondo E, Delamater AM, Perreira K, Van Horn L, et al. Theoretical foundations of the Study of Latino (SOL) Youth: implications for obesity and cardiometabolic risk. Ann Epidemiol. 2014; 24: 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutrition Data System for research - NDSR [computer program]. Version 2010. Minneapolis, MN: Nutrition Coordinating Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casagrande SS, Sotres-Alvarez D, Avilés-Santa L, O’Brien MJ, Palacios C, Pérez CM, et al. Variations of dietary intake by glycemic status and Hispanic/Latino heritage in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018; 6: e000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattei J, Sotres-Alvarez D, Daviglus ML, Gallo LC, Gellman M, Hu FB, et al. Diet Quality and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors Vary by Hispanic and Latino Ethnic Background in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Nutr. 2016; 146: 2035–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keast DR, Hill Gallant KM, Albertson AM, Gugger C, Holschuh N. Associations between yogurt, dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and obesity among US children aged 8–18 years: NHANES, 2005–2008. Nutrients. 2015; 7: 1577–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berner LA, Keast DR, Bailey RL, Dwyer JT. Fortified foods are major contributors to nutrient intakes in diets of US children and adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014; 114: 1009–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branum AM, Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC. Trends in caffeine intake among US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014; 133 (3): 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velázquez-López L, Santiago-Díaz G, Nava-Hernández J, Muñoz-Torres AV, Medina-Bravo P, Torres-Tamayo M. Mediterranean-style diet reduces metabolic syndrome components in obese children and adolescents with obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2014; 14: 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Gillespie C, Welsh JA, Hu FB, Yang Q. Usual intake of added sugars and lipid profiles among the US adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2010. J Adolesc Health. 2015; 56: 352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SAS software Version 9.3. Copyright © 2018. SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrick KA, Rossen LM, Parsons R, Dodd KW. Estimating usual dietary intake from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data using the National Cancer Institute method. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2018; 178: 1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin L A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989; 45: 255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrasco JL, Jover L. Estimating the generalized concordance correlation coefficient through variance components. Biometrics. 2003; 59: 849–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnhart HX, Haber M, Song J. Overall concordance correlation coefficient for evaluating agreement between multiple observers. Biometrics. 2002; 58: 1020–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bland JM, Altman DG. Comparing methods of measurement: why plotting difference against standard method is misleading. Lancet. 1995; 346: 1085–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giavarina D Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochemia Medica. 2015; 25: 141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuczmarski RJ. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States; methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002; 11: 246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Cancer Institute. Measurement error webinar series: Webinar 3, estimating usual intake distributions for dietary components consumed episodically. Available from: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/events/measurement-error/#session. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 42.National Cancer Institute. Usual dietary intakes: Food intakes, U.S. population, 2007–10. Available from: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/#national. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- 43.Kipnis V, Midthune D, Buckman DW, Dodd KW, Guenther PM, Krebs Smith SM, et al. Modeling data with excess zeros and measurement error: application to evaluating relationships between episodically consumed foods and health outcomes. Biometrics. 2009; 65: 1003–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verly-Jr E, Fisberg RM, Cesar CLG, Marchioni DML. Sources of variation of energy and nutrient intake among adolescents in São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2010; 26: 2129–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreno LA, Gottrand F, Huybrechts I, Ruiz JR, González-Gross M, DeHenauw S, HELENA Study Group. Nutrition and Lifestyle in European Adolescents: The HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Adv Nutr. 2014; 5: 615S–623S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.