Abstract

Objective

To identify pertinent clinical variables discernible on the day of hospital admission that can be used to assess risk for hospital-acquired-VTE (HA-VTE) in children.

Study design

The Children’s Hospital Acquired Thrombosis (CHAT) Registry is a multi-institutional registry for all hospitalized participants aged 0-21 years diagnosed with a HA-VTE and non-VTE controls. A risk assessment model (RAM) for the development of HA-VTE using demographic and clinical VTE risk factors present at hospital admission was derived using weighted logistic regression and the least absolute shrinkage and selection (Lasso) procedure. The models were internally validated using 5-fold cross-validation. Discrimination and calibration were assessed using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit, respectively.

Results

Clinical data from 728 HA-VTE cases and 839 non-VTE controls, admitted between January 2012 and December 2016, were abstracted. Statistically significant RAM elements included: age <1 year and 10-22 years, cancer, congenital heart disease, other high-risk conditions (inflammatory/autoimmune disease, blood-related disorder, protein-losing state, total parental nutrition dependence, thrombophilia/personal history of VTE), recent hospitalization, immobility, platelet count >350 K/uL, central venous catheter, recent surgery, steroids, and mechanical ventilation. AUROC was 0.78 (95% CI 0.76-0.80).

Conclusion

Once externally validated, this RAM will identify those who are at low-risk as well as the highest-risk groups of hospitalized children for investigation of prophylactic strategies in future clinical trials.

Keywords: Venous thromboembolism, risk assessment model, risk factor, children, risk prediction

The incidence of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (HA-VTE), defined as a VTE that develops while hospitalized, has increased in children by 70-200% (1, 2). Due to the rise in medically complex pediatric patients, the incidence of HA-VTE is expected to continue being a significant hospital-associated comorbid condition. This increase is largely driven by more effective, although more invasive treatments in children with serious and life-threatening disorders, such as placement of central venous catheters (CVCs) and prolonged survival in children with chronic diseases (1, 3).

The first critical step in reducing the incidence of HA-VTE is identifying risk of HA-VTE using a risk assessment model (RAM), a calculated combination of variables shown to predict a particular medical outcome such as VTE (4). In hospitalized, adult medical patients, VTE RAMs are regularly administered at hospital admission (5-7). Available pediatric RAMs have mostly been developed in a single center, using retrospective data and/or have not been thoroughly validated (8-13). Most of the currently available pediatric RAMs showed poor calibration when external validation was assessed (14). For adults, the recommendation is to assess HA-VTE and HA-bleeding risk and provide pharmacologic prophylaxis to those for whom the benefits outweigh the risks. This strategy has led to millions of individuals exposed to anticoagulants to prevent thousands of VTE events (15, 16). In order to limit unnecessary anticoagulant exposure in children and inform risk-stratified clinical trials of VTE prevention, RAMs must be rigorously derived, informed by broadly-representative multicenter data, and validated.

In an effort to overcome current gaps in knowledge on risk factors and RAMs for HA-VTE in children, the multicenter Children’s Hospital Acquired Thrombosis (CHAT) Registry was established (17). Using the Registry, the goal of this study was to derive and internally validate a pediatric RAM that will accurately predict the risk of developing a HA-VTE at hospital admission and help guide future trials of thromboprophylaxis in high-risk patients. Specifically, our primary objective was to identify demographic and clinical variables present and knowable on the day of hospital admission that increase HA-VTE risk. The secondary objective was to use these risk factors to derive a RAM that is applicable to hospitalized children on the day of admission, toward the determination of HA-VTE risk.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a multicenter, retrospective case-control study from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2016 using participants from six of the nine participating institutions within the CHAT Registry. Participants admitted from 2012 to 2016 were included from four of the hospitals (Children’s Hospital Colorado, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Children’s Mercy Kansas City and CHOC Children’s Hospital) and two hospitals (Boston Children’s Hospital and Akron Children’s Hospital) included data from 2012-2015 or 2014-2015. All participating institutions are large, tertiary care, children’s hospitals with separate units for critically ill children and neonates as well as dedicated teams caring for various pediatric subspecialties. The institutional review board at each of the participating hospitals approved the study and a waiver of consent was granted. The coordinating center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles performed all data quality checks for accuracy and completeness for each institution. TRIPOD reporting guidelines for prognostic studies were followed (18).

Study participants

Eligible participants for development of the risk model were hospitalized children aged 0-21 years within the CHAT Registry. The eligibility criteria for participant inclusion within the CHAT Registry has been previously published and presented under Statistical Analysis (17). Briefly, all cases of a HA-VTE that occurred over a full calendar year were entered into the CHAT Registry from each institution. HA-VTE cases required an imaging-confirmed VTE diagnosed during hospitalization and they were excluded if they had signs or symptoms of VTE upon hospital admission. Non-VTE controls were hospitalized patients without a diagnosis of VTE and matched on institution and admission year to HA-VTE cases. The analytical cohort for the RAM development was restricted to the hospitals that entered a full years’ worth of HA-VTE cases and sampled non-VTE controls into the CHAT Registry. HA-VTE cases were excluded from RAM development if they were diagnosed with an asymptomatic VTE identified during radiographical imaging for other reasons.

Predictors

Only variables within the CHAT Registry present and knowable at admission, or within 24 hours of admission, were assessed for inclusion in the RAM. Data collected from participants’ medical records and entered into the CHAT Registry included demographics, past medical history, hospital course details such as placement of a central venous catheter, surgeries, procedures, laboratory values, infections, and medications. For HA-VTE cases, details regarding VTE type, diagnosis and treatment were also collected. A description of data elements collected within the CHAT Registry has been previously described and based on previous studies evaluating HA-VTE in children (8-12, 17, 19-23). Data were collected and managed using standardized case report forms within Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a free, secure, web-based software platform (24, 25). Access to the case report forms was provided to each participating center with detailed data dictionaries to ensure reproducible data collection. Data in the CHAT Registry were routinely screened to identify missing or inconsistent data entries.

Definitions

The diagnosis of a VTE required a confirmatory radiology report from each institution based on the final attending radiologist interpretation of diagnostic imaging at each institution. Imaging consisted of Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography scan, venography, echocardiogram or magnetic resonance imaging. VTE symptoms were defined as change in limb temperature or color, pain, limb swelling, change in mental status, hypoxemia, shortness of breath, vomiting, malfunction of CVC, or use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) for malfunction of CVC. CVC-associated VTE was defined as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) found in the same vein where a CVC was inserted or attempted to be inserted. Immobility was defined as a Braden mobility score of 1 or 2 (completely immobile or very limited immobility) (26). An autoimmune or inflammatory condition was defined as rheumatological disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile rheumatoid arthrosis, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease. A recent hospitalization was defined as admission to any hospital within 30 days prior to the current hospitalization, and recent surgery was any surgical procedure lasting >60 minutes within 2 weeks of hospital admission.

Statistical Analyses

The analytical goal was to identify demographic and clinical variables that could significantly predict risk of HA-VTE using data from the CHAT Registry. The cohort for this study comprised cases who developed HA-VTE and non-VTE controls. The non-VTE controls were randomly sampled from a complete list of children without HA-VTE at each participating institution and admitted in the same year as that institution’s HA-VTE cases. A large proportion of pediatric patients from the participating hospitals in the CHAT Registry had a hospital length of stay <48 hours, so the sampled non-VTE controls were enriched for patients with longer hospital stay to improve estimation (17), specifically the sampling proportion of non-VTE controls with hospital length of stay less than 48 hours was set to 20% (Appendix 1; available at www.jpeds.com).

Chi-square test was used to analyze participant demographic variables. Weighted logistic regression was utilized to examine the association between baseline variables (prior to admission and at day of admission) and development of HA-VTE after admission. Non-VTE controls were weighted by the inverse sampling probability to recapitulate the population from which the controls were sampled (Appendix 2; available at www.jpeds.com). Participant demographics, past medical history, and other baseline data that pertained to the participant’s hospitalization, such as platelet count, Braden score, steroid use, and history of surgeries, placement of a CVC, and other medical procedures leading up to the day of admission, that had frequency of greater than five cases were initially individually assessed in a univariable analysis of HA-VTE, with year of admission and the hospital sites also included as covariates in each univariable model to adjust for effects of time and the treating hospital. Variables that met the threshold of P < .20 in univariable analysis were included in multivariable analysis. Specific interaction effects that were biologically plausible were tested separately (main effects and interaction term only) and considered among the candidate predictors when the p-value of the interaction term was less than 0.10. Low frequency variables (determined as those with 5 or fewer encounters) were not included in the analysis.

The least absolute shrinkage and selection (Lasso) method (as implemented in the GLMNET procedure in R) was used to build the multivariable weighted logistic regression model of HA-VTE incidence (27), starting with a model that included all of the key predictors and interactions that had sufficient frequency and were significant in the univariable analysis. Year of admission and hospital site were not included in the multivariable model as these would not be relevant in a generally applicable risk assessment model. Variables remaining after the Lasso procedure were included in a standard weighted logistic regression analysis to obtain the final model.

Internal validation of the RAM was performed by dividing the sample into five random, equal size subsets each comprising a full year’s case/control dataset for the selected hospital site and admission year (28). The method above for developing the multivariable predictor model was performed independently on samples comprising four of the five subsets and tested on the left-out subset, for each of the five subsets in turn. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve derived from this internal cross-validation was used to assess the prediction model performance.

As the usual Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit (GOF) test (29) was not applicable to our complex sampling setting, we applied an analogous method to assess goodness of fit to assess calibration. The hoslem.test procedure in R was used to divide the sample into 10 groups with approximately homogeneous prediction probabilities. This decile group variable was then added as a factor along with the linear predictor as a covariate in a weighted logistic regression analysis. The significance test of the null hypothesis that the added factor does not improve the model thereby essentially serves as a test of goodness of fit of the original model, with rejection indicating lack of fit. There was a statistically significant (p<0.001) systematic deviation between the model predictions with versus without the additional decile factor, which was nevertheless small in magnitude. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14 and R version 3.5.1 statistical software packages (30, 31).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

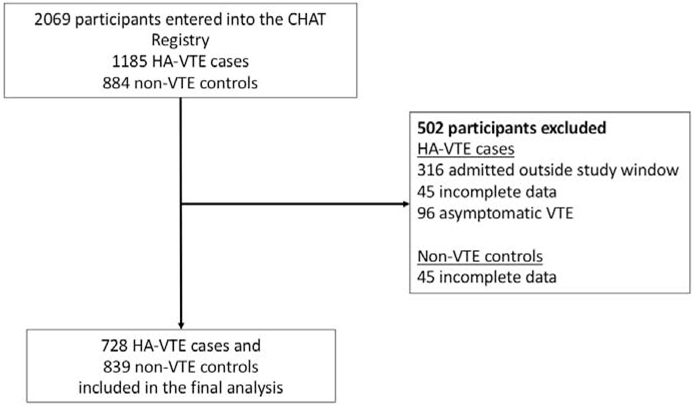

From January 2012 to July 2019, 1185 HA-VTE cases and 884 non-VTE controls were enrolled into the CHAT Registry. For risk variable analysis and RAM development, 728 HA-VTE cases and 839 non-VTE controls were eligible for inclusion during the January 2012 to December 2016 study period (Table 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Exclusion of participants was predominantly due to Registry participants being outside the 2012-2016 RAM development study window (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Number of participants from each institution included in the CHAT risk assessment model development.

| Institution | HA-VTE cases included | Non-VTE controls included | Hospital admissions 2012-2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCH* | 48 | 73 | 54, 936 |

| CHCO | 210 | 255 | 92, 635 |

| CHLA | 260 | 274 | 72, 653 |

| CMH** | 12 | 11 | 28, 872 |

| CHOC | 119 | 131 | 54, 939 |

| CMHC | 79 | 95 | 54, 473 |

Reflects participants and admission data from 2012-2016 only

Reflects participants and admission data from 2014-2015 only

BCH, Boston Children’s Hospital; CHCO, Children’s Hospital Colorado; CHLA, Children’s Hospital Los Angles; CMH, Akron Children’s Hospital; CHOC, CHOC Children’s Hospital; CHMC, Children’s Mercy Kansas City

Figure 1.

Reasons for exclusion of participants from the CHAT Registry to include in the risk assessment model development.

The median age at hospital admission for HA-VTE cases was 2.7 years (IQR 0.23-13.6 years) versus 6 years (IQR 1.7-13.0 years) for controls (p<0.0001) (Table 2). The majority of participants were male in both the HA-VTE case (n=416, 57%) and control (n=438, 52%) groups. Sex and ethnicity were not associated with HA-VTE risk, and association of VTE risk with race was not performed due to 45% of cases listed as “other”. Congenital heart disease was the predominant medical diagnosis for HA-VTE cases, 158 (22%) and controls, 53 (6%).

Table 2.

Demographics summary by participant type.

| Variable | Participant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA-VTE n (%) 728 (46.5) |

Non-VTE n (%) 839 (53.5) |

Total n (%) 1567 (100) |

||

| Age at admission (median, range) | 2.7 (0, 21.7) | 6.0 (0, 21. 4) | 5.0 (0, 21.7) | |

| Age at admission | < 1 years | 287 (39) | 160 (19) | 447 (29) |

| 1 - 10 years | 193 (27) | 390 (46) | 583 (37) | |

| 10 - 22 years | 248 (34) | 289 (34) | 537 (34) | |

| Sex | Male | 416 (57) | 438 (52) | 854 (54) |

| Female | 312 (43) | 401 (48) | 713 (46) | |

| Race | White | 368 (51) | 278 (33) | 646 (41) |

| Asian | 53 (7) | 33 (4) | 86 (5) | |

| Black or African American | 71 (10) | 53 (6) | 124 (8) | |

| Other | 236 (32) | 475 (57) | 711 (45) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 236 (32) | 301 (36) | 537 (34) |

| White/Non-Hispanic | 414 (57) | 438 (52) | 852 (54) | |

| Other | 78 (11) | 100 (12) | 178 (11) | |

| Past Medical history | Cancer non-hematologic | 28 (4%) | 48 (6%) | 76 (5%) |

| Cancer hematologic | 50 (7%) | 39 (5%) | 89 (6%) | |

| Congenital heart disease | 158 (22%) | 53 (6%) | 211 (13%) | |

| Other high-risk disease* | 84 (12%) | 44 (5%) | 128 (8%) | |

Other high-risk diseases refer to: inflammatory/autoimmune disease, hematologic disease, thrombophilia/history of VTE, total parental nutrition dependence and protein losing state

Hospital-Acquired Venous Thromboembolism Participants

At the time of HA-VTE diagnosis, 214 (29%) were in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), followed by the cardiac unit 161 (22%), and the general pediatric unit, 145 (20%) (Table 3). The median time from hospital admission to HA-VTE diagnosis was 9 days (IQR 4.5-20.0 days) and the median total hospital admission length of stay was 30 days (IQR 15-61 days).

Table 3.

Summary of characteristics of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (HA-VTE) cases, n=728.

| Variable | Summary statistics n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median Age of patient at HA-VTE diagnosis, years, median (range) | 2.9 (0-21.7) | |

| Inpatient location at the time of VTE diagnosis | Pediatric intensive care unit | 214 (29) |

| Cardiac intensive care unit | 161 (22) | |

| General pediatric | 145 (20) | |

| Hematology/Oncology | 95 (13) | |

| Neonatal intensive care unit | 37 (5) | |

| Surgical unit | 23 (3) | |

| Gastroenterology | 16 (2) | |

| Pulmonary | 15 (2) | |

| Emergency room | 10 (1) | |

| Neurology unit | 3 (0) | |

| Other | 9 (1) | |

| Type of VTE | DVT of the upper/lower extremity | 632 (87) |

| Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis | 32 (4) | |

| DVT of an abdominal vein | 23 (3) | |

| Pulmonary embolus | 20 (3) | |

| Other | 21 (3) | |

| Method of VTE detection | Ultrasound | 644 (88) |

| CT angiogram or venogram | 32 (4) | |

| MRI angiogram or venogram | 29 (4) | |

| Echocardiogram | 16 (2) | |

| X-ray venogram | 4 (1) | |

| Other | 3 (0) | |

PE, CT, computerized tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Over 80% of the HA-VTE events had a CVC-associated VTE (n=588, 81%), and the most common type of CVC associated with a VTE was a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC, n=361, 61%). Most HA-VTE cases had a DVT of an extremity, 632 (87%), followed by 32 (4%) with a cerebral sinus venous thrombosis (Table 3). Doppler ultrasonography was used to diagnose 644 (88%) cases with a HA-VTE.

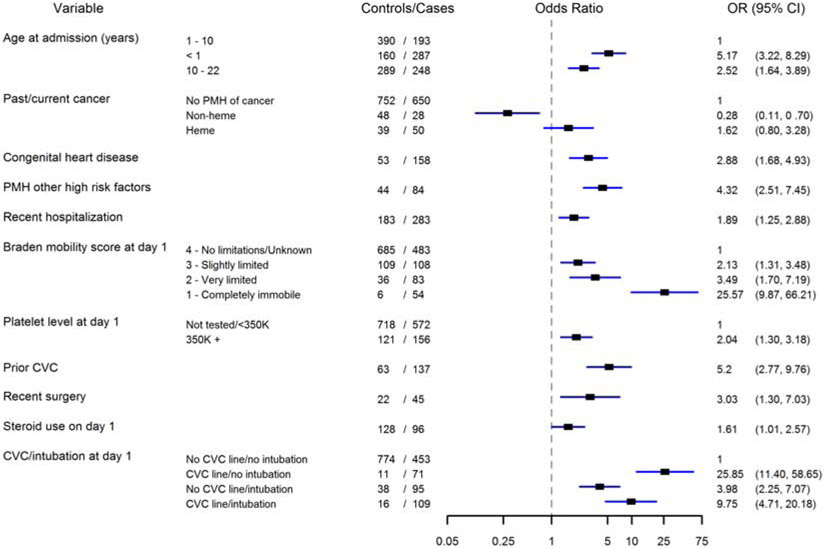

Risk Assessment Model

Over 100 individual data elements were initially screened for VTE risk, but most were not further assessed due to the low frequency of the characteristic. Thirty-five variables with p<0.20 in the univariable analysis were further assessed via multivariable analysis to identify high-risk VTE variables present in participants at or within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. Eleven clinically relevant and statistically significant variables were identified as predictors for HA-VTE using weighted logistic regression and the Lasso procedure (Figure 2). These included: (1) age less than 1 year or between 10-22 years, (2) diagnosis of cancer, (3) diagnosis of congenital heart disease, (4) diagnosis of other high risk diseases, which includes inflammatory/autoimmune disease, blood-related disorder, protein-losing state, total parental nutrition dependence, thrombophilia/history of VTE, (5) recent hospitalization, (6) immobility based on the mobility component of the Braden Scale, (7) platelet count >350 K/uL (8) CVC in place prior to hospital admission, (9) recent surgery, (10) steroids given at admission, and (11) the interaction of intubation and placement of a CVC at admission (Figure 2). Intubation and CVC placement at admission were both independent predictors of VTE with a significant interaction. CVC or intubation alone were identified to increase risk of VTE, however the presence of both did not further increase the risk of VTE. The calculation for the linear predictor of the RAM is provided in Appendix 3 (available at www.jpeds.com). Internal validation of the RAM gave an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.78 (CI 0.76-0.80%) (Figure 3; available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure 2.

Forest plot from Weighted Logistic Regression (variable selection from Lasso procedure).

*PMH, past medical history

**Other high risk factors include: inflammatory/autoimmune disease, hematologic disease, thrombophilia/history of VTE, total parental nutrition dependence and protein losing state

DISCUSSION

Due to the growing awareness and frequency of pediatric HA-VTE and associated complications, there is need for effective risk assessment and prevention strategies. This study, using data from over 700 HA-VTE cases from the CHAT Registry, has addressed this knowledge gap by developing a HA-VTE RAM with an AUC of 0.78 and goodness of fit assessment indicating that the model-based HA-VTE probability is accurate. Significant variables identified to predict increased risk of HA-VTE in children at hospital admission included age less than one year or adolescent/young adult; having cancer, congenital heart disease, or other identified high-risk diseases; recent hospitalization or surgery; receipt use of steroids; immobility; presence of a CVC; an elevated platelet count; or tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Some of the VTE risk variables in our RAM, such as age less than one year, immobility, CVC, and mechanical ventilation, have been identified with previous pediatric HA-VTE RAM development (8-10, 12, 13). Many of the remaining risk variables in our model have been shown to be significant risk factors for HA-VTE development in children, but this is the first time many of them have withstood the rigor of risk model development. One risk variable in our RAM, an elevated platelet count, has not been identified in previous pediatric RAM development or analysis of HA-VTE risk factors. Therefore our model may provide new insights into pediatric thrombosis risk and provide a relatively easy biomarker to obtain upon hospital admission to assess VTE risk.

Infants and adolescents were confirmed as high-risk in our RAM, which is consistent with younger children, especially those under 1 year of age, being the most common age group for developing a HA-VTE, along with adolescents (23, 32). Other previously known at-risk pediatric populations, that are included in are RAM are those with cancer, congenital heart disease, autoimmune diseases, hematological disease, history of a VTE, thrombophilia, and recent surgery (23, 33-35). Cancer is a well-known risk for VTE, due to requiring prothrombotic chemotherapeutic agents such as asparaginase and steroids, surgeries, CVCs, and the hypercoagulable state of cancer itself (36-40). Children with congenital heart disease are at high-risk for HA-VTE due critical illness, requiring CVCs, and surgeries as well as cardiopulmonary bypass, which can lead to activation of the coagulation system (13, 41-43).

In contrast to four of the previous pediatric RAMs, results from this study did not include length of hospital stay or the association of infection with HA-VTE risk (8-10, 12, 13). This is due to our RAM assessing HA-VTE risk on day one of hospital admission, thus prolonged hospital stay was not included. The risk of infections may be an underestimation, given that some infections that may be present on admission are diagnosed only after the first day of hospitalization. Future RAMs from the CHAT Registry will address knowledge gaps on HA-VTE risk re-assessment at 3-4 days post-admission. Of note, over 50% of the HA-VTE cases in our study were critically ill and admitted to an intensive care unit, whether cardiac, neonatal, or pediatric. Critical illness and admission to an ICU was not a variable in our RAM, in contrast to a previous RAM as well as a systematic review and meta-analysis of pediatric HA-VTE risk factors (11, 12). Variables in our model, such as intubation and mechanical ventilation, presence of a CVC, and/or immobility most likely represent the critically ill population.

HA-VTE RAMs developed for adult patients share many of the same risk variables as our RAM. These include having cancer, a history of VTE or known thrombophilia, inflammatory disease, an elevated platelet count, immobility, and a recent surgery (15, 44-46). Other variables are more characteristic of the adult population, such as being elderly, obese, having congestive heart failure or myocardial infarction, and the lack of a CVC as a risk factor, emphasizing the importance of creating a pediatric specific model. The risk factors that are similar between populations (cancer, immobility, inflammation/elevated platelet count, and surgery) are indicative of the underlying causation of thrombosis based on Virchow’s triad (venous stasis, activation of coagulation, and intimal damage of the vein) (47, 48).

The pediatric VTE risk models created previously have been single center, created for specific patient populations, such as those who are critically ill, or have not been externally validated (8-10, 12, 49). Strengths of our study include larger size, multi-institutional design, and the exclusion of asymptomatic HA-VTE. Recent studies have shown asymptomatic thrombosis development in patients may not be clinically significant and these patients may not require anticoagulation treatment (50, 51). Therefore by including only symptomatic VTE cases to build the RAM, we may identify a higher risk group at the time of admission who might benefit from prophylactic measures. Additionally, a larger sample size provided us with better power to identify risk factors of HA-VTE. Another strength of our model is the applicability toward assessing HA-VTE risk on day 1 of hospital admission, which in the future may permit investigation of early intervention strategies. These interventions, such as mechanical and pharmacological prophylaxis, need to be considered at admission in order to permit ample time to prevent HA-VTE. Both of these prophylactic measures are routinely used in the adult populations and are efficacious in preventing VTE, but their utility and proper patient selection are as yet unknown in children (52-54).

One limitation of the study is the proportion of neonates represented in our study cohort, which may have skewed the data towards risk factors more predominant for this age group. Previous studies have shown the majority of HA-VTE cases occur in children under one year of age, therefore even if the data are skewed this may be a true representation of VTE risk in children (23, 55). After external validation of our model, we will determine if these neonatal factors are overrepresented and if model adjustment is necessary. In addition, not all risk factors are necessarily causal and over time this model can be refined. Another limitation is this study included large children’s hospitals for the RAM derivation, therefore this RAM may not be valid in all types of hospitals caring for children, representing a broader spectrum of case-mix index. To overcome this limitation, we will investigate the external validity of the RAM in multiple centers across the U.S. including large tertiary care centers and smaller community hospitals. A third limitation was the inability to analyze race as a risk factor for HA-VTE risk, due to 45% of cases having their race identified as “other”. Lastly, we did not perform routine screening for HA-VTE, thus some VTE events may have been missed or symptoms may have been poorly documented in the medical record.

A population-specific RAM, as well as weighting of RAM components and exploration of potential enhanced prognostic utility of biomarkers, are aims of an ongoing, grant-funded prospective validation study. In addition, future studies may examine (1) addition of dynamic variables to this current RAM to enable reassessment of VTE risk throughout hospitalization, and (2) assessment of bleeding risk in hospitalized children receiving prophylactic and treatment dosing of anticoagulation.

In conclusion, VTE continues to be a serious problem for hospitalized pediatric patients for whom risk could not previously be assessed. In order to better identify the at-risk patient population, a pediatric HA-VTE risk model was developed through the large, multi-institutional CHAT Registry. Eleven risk factors were found to be statistically significant predictors of HA-VTE and included in our final RAM with an acceptable AUC. Validation in other centers is needed and, once externally validated, our RAM can define populations for whom the benefit of thromboprophylaxis outweighs the risks. This approach will also allow the lower risk population to be spared prevention strategies with potential adverse events in terms of bleeding, medication reactions, discomfort, and additional cost.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Cecilia Patino-Sutton, MD (University of Southern California) and Ernest Amankwah, PhD (Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital) for their review of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the time and efforts of the clinical research coordinators who supported the execution of this study: Jill Bradisse (CMH), Kim Cattivelli (BCH), Allaura Cox (CHCO), Marissa Erickson (CHOC), Lori Sahakian (BCH) and Natalie Laing Smith (CHCO). We also acknowledge the faculty and supporters of the American Society of Hematology Clinical Research Training Institute for the mentorship provided through this program to J.J. in her work on this study.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (UL1TR001855 [to J.J.]); The Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society Mentored Research Award, supported by an independent educational grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. (to A.M. and J.J.); the CHOC Children’s Hospital and University of California Irvine Physician-Scientist Research Award program (to A.M.); the Children’s Hospital Saban Research Mentored Career Development Award (to J.J.). Funding sources did not have a role in study design, data analysis, writing or submission of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CHAT

Children’s Hospital Acquired Thrombosis

- CVC

Central venous catheter

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- HA-VTE

Hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism

- RAM

Risk assessment model

- VTE

Venous thromboembolism

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of this study were presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting, << >>, 2019, << >>.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children's hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1001–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter SL, Richardson T, Hall M. Increasing rate of pulmonary embolism diagnosed in hospitalized children in the United States from 2001 to 2014. Blood Adv. 2018;2(12):1403–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moons KG, Kengne AP, Woodward M, Royston P, Vergouwe Y, Altman DG, et al. Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart. 2012;98(9):683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decousus H, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, Chong BH, Froehlich JB, Kakkar AK, et al. Factors at admission associated with bleeding risk in medical patients: findings from the IMPROVE investigators. Chest. 2011;139(1):69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha AT, Paiva EF, Lichtenstein A, Milani R Jr., Cavalheiro CF, Maffei FH. Risk-assessment algorithm and recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical patients. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3(4):533–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, Lloyd JF, Evans RS, Aston VT, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):947–54 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arlikar SJ, Atchison CM, Amankwah EK, Ayala IA, Barrett LA, Branchford BR, et al. Development of a new risk score for hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in critically-ill children not undergoing cardiothoracic surgery. Thromb Res. 2015;136(4):717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atchison CM, Arlikar S, Amankwah E, Ayala I, Barrett L, Branchford BR, et al. Development of a new risk score for hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in noncritically ill children: findings from a large single-institutional case-control study. J Pediatr. 2014;165(4):793–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branchford BR, Mourani P, Bajaj L, Manco-Johnson M, Wang M, Goldenberg NA. Risk factors for in-hospital venous thromboembolism in children: a case-control study employing diagnostic validation. Haematologica. 2012;97(4):509–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahajerin A, Branchford BR, Amankwah EK, Raffini L, Chalmers E, van Ommen CH, et al. Hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in pediatrics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors and risk-assessment models. Haematologica. 2015;100(8):1045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharathkumar AA, Mahajerin A, Heidt L, Doerfer K, Heiny M, Vik T, et al. Risk-prediction tool for identifying hospitalized children with a predisposition for development of venous thromboembolism: Peds-Clot clinical Decision Rule. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atchison CM, Amankwah E, Wilhelm J, Arlikar S, Branchford BR, Stock A, et al. Risk factors for hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in critically ill children following cardiothoracic surgery or therapeutic cardiac catheterisation. Cardiol Young. 2018;28(2):234–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahajerin A, Jaffray J, Branchford B, Stillings A, Krava E, Young G, et al. Comparative validation study of risk assessment models for pediatric hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(3):633–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darzi AJ, Karam SG, Charide R, Etxeandia Ikobaltzeta I, Cushman M, Gould MK, et al. Prognostic factors for VTE and Bleeding in Hospitalized Medical Patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schunemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, Kahn SR, Beyer-Westendorf J, Spencer FA, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffray J, Mahajerin A, Young G, Goldenberg N, Ji L, Sposto R, et al. A multi-institutional registry of pediatric hospital-acquired thrombosis cases: The Children's Hospital-Acquired Thrombosis (CHAT) project. Thromb Res. 2018;161:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Network E. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement 2019. [Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/tripod-statement/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Carter JH, Langley JM, Kuhle S, Kirkland S. Risk Factors for Central Venous Catheter-Associated Bloodstream Infection in Pediatric Patients: A Cohort Study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(8):939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revel-Vilk S, Yacobovich J, Tamary H, Goldstein G, Nemet S, Weintraub M, et al. Risk factors for central venous catheter thrombotic complications in children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(17):4197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amankwah EK, Atchison CM, Arlikar S, Ayala I, Barrett L, Branchford BR, et al. Risk factors for hospital-sssociated venous thromboembolism in the neonatal intensive care unit. Thromb Res. 2014;134(2):305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Greenup RA, Liu H, Sato TT, Havens PL. Incidence and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68(1):52–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemoto CM, Sohi S, Desai K, Bharaj R, Khanna A, McFarland S, et al. Hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in children: incidence and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergstrom N, Braden BJ. Predictive validity of the Braden Scale among Black and White subjects. Nurs Res. 2002;51(6):398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tibshiranu R Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1996;58:267–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braga-Neto UM, Dougherty ER. Is cross-validation valid for small-sample microarray classification? Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, Lemeshow S. A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med. 1997;16(9):965–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. StataCorp. College Station, TX: Stata Statistical Software; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Team RC. A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Core Team; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrew M, David M, Adams M, Ali K, Anderson R, Barnard D, et al. Venous thromboembolic complications (VTE) in children: first analyses of the Canadian Registry of VTE. Blood. 1994;83(5):1251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffray J, Witmer C, O'Brien SH, Diaz R, Ji L, Krava E, et al. Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters Lead to a High Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Children. Blood. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Ommen CH, Heijboer H, Buller HR, Hirasing RA, Heijmans HS, Peters M. Venous thromboembolism in childhood: a prospective two-year registry in The Netherlands. J Pediatr. 2001;139(5):676–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowak-Gottl U, Junker R, Kreuz W, von Eckardstein A, Kosch A, Nohe N, et al. Risk of recurrent venous thrombosis in children with combined prothrombotic risk factors. Blood. 2001;97(4):858–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caruso V, Iacoviello L, Di Castelnuovo A, Storti S, Mariani G, de Gaetano G, et al. Thrombotic complications in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis of 17 prospective studies comprising 1752 pediatric patients. Blood. 2006;108(7):2216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaffray J, Mahajerin A, Croteau S, Silvery M, Krava E, Stillings A, Young G, Branchford B Central Venous Catheters, a Major Culprit for Pediatric Venous Thrombosis: A Report from the Children's Hospital Acquired Thrombosis (CHAT) Project. Blood. 2017;130:3706. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Journeycake JM, Buchanan GR. Catheter-related deep venous thrombosis and other catheter complications in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rickles FR. Mechanisms of cancer-induced thrombosis in cancer. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2006;35(1-2):103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paz-Priel I, Long L, Helman LJ, Mackall CL, Wayne AS. Thromboembolic events in children and young adults with pediatric sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Christensen MA, Ghanayem NS, Kuhn EM, Havens PL. Incidence and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in critically ill children with cardiac disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33(1):103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silvey M, Hall M, Bilynsky E, Carpenter SL. Increasing rates of thrombosis in children with congenital heart disease undergoing cardiac surgery. Thromb Res. 2018;162:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thom KE, Hanslik A, Male C. Anticoagulation in children undergoing cardiac surgery. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37(7):826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zakai NA, Callas PW, Repp AB, Cushman M. Venous thrombosis risk assessment in medical inpatients: the medical inpatients and thrombosis (MITH) study. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(4):634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caprini JA. Thrombosis risk assessment as a guide to quality patient care. Dis Mon. 2005;51(2-3):70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menendez JJ, Verdu C, Calderon B, Gomez-Zamora A, Schuffelmann C, de la Cruz JJ, et al. Incidence and risk factors of superficial and deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in children. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(11):2158–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nifong TP, McDevitt TJ. The effect of catheter to vein ratio on blood flow rates in a simulated model of peripherally inserted central venous catheters. Chest. 2011;140(1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Setty BA, O'Brien SH, Kerlin BA. Pediatric venous thromboembolism in the United States: a tertiary care complication of chronic diseases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(2):258–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faustino EV, Spinella PC, Li S, Pinto MG, Stoltz P, Tala J, et al. Incidence and acute complications of asymptomatic central venous catheter-related deep venous thrombosis in critically ill children. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):387–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones S, Butt W, Monagle P, Cain T, Newall F. The natural history of asymptomatic central venous catheter-related thrombosis in critically ill children. Blood. 2019;133(8):857–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zayed Y, Kheiri B, Barbarawi M, Banifadel M, Abdalla A, Chahine A, et al. Extended duration of thromboprophylaxis for medically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Intern Med J. 2020;50(2):192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horner D, Stevens JW, Pandor A, Nokes T, Keenan J, de Wit K, et al. Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with temporary lower limb immobilization after injury: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(2):422–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ho KM, Tan JA. Stratified meta-analysis of intermittent pneumatic compression of the lower limbs to prevent venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Circulation. 2013;128(9):1003–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monagle P, Adams M, Mahoney M, Ali K, Barnard D, Bernstein M, et al. Outcome of pediatric thromboembolic disease: a report from the Canadian Childhood Thrombophilia Registry. Pediatr Res. 2000;47(6):763–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.