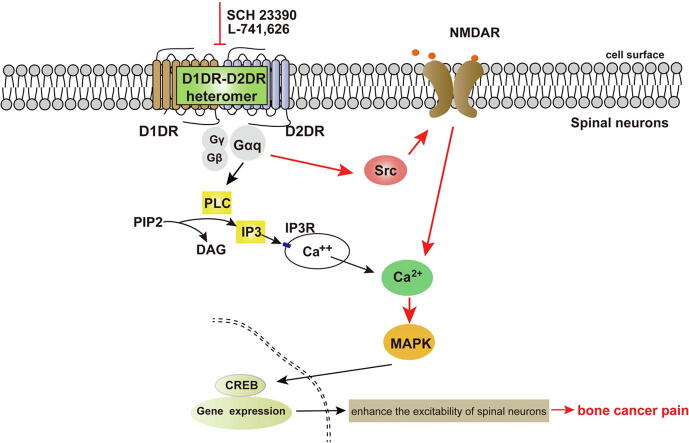

Graphical abstract

Keywords: NMDA receptor, Dopamine D1 receptor, Dopamine D2 receptor, Bone cancer pain, Src kinase, Gαq protein

Abstract

Introduction

Spinal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is vital in chronic pain, while NMDAR antagonists have severe side effects. NMDAR has been reported to be controlled by G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), which might present new therapeutic targets to attenuate chronic pain. Dopamine receptors which belong to GPCRs have been reported could modulate the NMDA-mediated currents, while their exact effects on NMDAR in chronic bone cancer pain have not been elucidated.

Objectives

This study was aim to explore the effects and mechanisms of dopamine D1 receptor (D1DR) and D2 receptor (D2DR) on NMDAR in chronic bone cancer pain.

Methods

A model for bone cancer pain was established using intra-tibia bone cavity tumor cell implantation (TCI) of Walker 256 in rats. The nociception was assessed by Von Frey assay. A range of techniques including the fluorescent imaging plate reader, western blotting, and immunofluorescence were used to detect cell signaling pathways. Primary cultures of spinal neurons were used for in vitro evaluation.

Results

Both D1DR and D2DR antagonists decreased NMDA-induced upregulation of Ca2+ oscillations in primary culture spinal neurons. Additionally, D1DR/D2DR antagonists inhibited spinal Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) and c-Fos expression and alleviated bone cancer pain induced by TCI which could both be reversed by NMDA. And D1DR/D2DR antagonists decreased p-NR1, p-NR2B, and Gαq protein, p-Src expression. Both Gαq protein and Src inhibitors attenuated TCI-induced bone cancer pain, which also be reversed by NMDA. The Gαq protein inhibitor decreased p-Src expression. In addition, D1DR/D2DR antagonists, Src, and Gαq inhibitors inhibited spinal mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) expression in TCI rats, which could be reversed by NMDA.

Conclusions

Spinal D1DR/D2DR inhibition eliminated NMDAR-mediated spinal neuron activation through Src kinase in a Gαq-protein-dependent manner to attenuate TCI-induced bone cancer pain, which might present a new therapeutic strategy for bone cancer pain.

Introduction

Chronic bone cancer pain is one of the most common pains in cancer patients with metastatic bone disease, and it has a severe impact on their life quality [1]. Common tumors like breast, kidney, prostate, and lung cancers easily metastasize to multiple bones to promote bone cancer pain [2]. Chronic bone cancer pain is complicated, and the mechanism is still not fully illuminated. The cancer cells can invade and destroy the bone, and release a variety of products with other inflammatory cells, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to activate the nociceptors [3], [4]. The noxious stimuli could also transmit to the spinal cord to promote the presynaptic neurons to release a variety of excitatory neurotransmitters, leading to the development of central sensitization, which contributes to chronic bone cancer pain [3], [4]. Glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter, acts on its receptors to exert its postsynaptic effect in the central nervous system (CNS) [5]. Among them, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) exerts critical effects in modulating the plasticity of neurons and excitatory synaptic transmission [6]. It is widely accepted that activated spinal NMDAR could promote the development of chronic pain [7]. However, the mechanisms by which NMDAR is regulated in bone cancer pain are still not fully elucidated, and the use of NMDAR antagonists like ketamine and MK801 result in very severe side effects that limit their clinical use [8], [9].

NMDAR has been reported to be regulated by GPCR stimulation. The dopamine receptors are GPCRs and have been reported to regulate NMDAR in different brain regions [10], [11], [12], [13]. It has been reported that D1DR couples to Gs/olf proteins to activate cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and that D2DR couples to Gi/o proteins to inhibit adenylyl cyclase (AC) [14]. D1DR and D2DR might enhance or decrease the NMDAR-mediated currents in a G-protein-dependent or independent manner through different pathways in the brain. However, the effects and mechanisms of D1DR and D2DR modulation of bone cancer pain also have not been elucidated.

D1DR and D2DR have been reported to form heteromers in brain, which in turn couple to Gαq protein [15]. Our previous research also indicated that spinal D1DR and D2DR could form complexes and promote chronic bone cancer pain through Gαq protein. The activation of Gαq protein has been reported to increase NMDAR function through Src protein-tyrosine kinase [16], [17]. Src kinase is a tyrosine kinase, and a Src inhibitor was reported to inhibit NMDAR function [18] and attenuate bone cancer pain [19]. Herein, D1DR and D2DR were hypothesized can activate NMDAR to promote bone cancer pain through Src kinase in a Gαq-reliant manner. For this purpose, intra-tibia inoculation of Walker 256 mammary gland carcinoma cells was used to induce bone cancer pain, which could mimic well the key features of human bone cancer pain [20], [21]. And this study may present a new strategy for attenuating chronic bone cancer pain.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was performed in accordance with the Interdisciplinary Principles and Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research, Testing, and Education issued by the New York Academy of Sciences Adhoc Committee on Animal Research. The animal testing was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (SYXK (Su) 2016–0011).

Materials

B-27, L-glutamic acid, deoxyribonuclease (DNase), fluorescent dye, anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), soybean trypsin inhibitor, fluo-8, and poly-l-lysine (PLL) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-p-p38 MAPK (p-p38), anti-p-JNK, anti-p-p44/42 MAPK (p-ERK1/2), anti-p38 MAPK, anti-JNK, anti-ERK1/2, and anti-rabbit/mouse IgG antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Donkey anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488 were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., (PA, USA). Fetal bovine serum, neurobasal medium, RPMI 1640 medium, and trypsin were purchased from Gibco (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The Gαq inhibitor YM 254,890 was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). L-741,626, SCH 23390, NMDA, and PP2, LY 23,959 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, UK). YM 254,896 and PP2 were dissolved in 2% DMSO, L-741,626 was dissolved in 25% DMSO, SCH 23390, NMDA and LY2359549 were dissolved in sterilized saline.

Experimental animals

Sprague-Dawley female rats (60–80 g and 180–220 g) were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center at Yangzhou University (Jiangsu, China). The rats were housed three per cage in a temperature and humidity controlled environment (24 ± 2 °C; 45% to 50% humidity) on a 12 h light/dark cycle (9:00 to 21:00) and randomly allocated to different groups based on their weight. Behavioral test was performed during the light cycle (9:00 to 17:00). Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.). There are several groups: Sham + Vehicle; TCI + Vehicle; TCI + NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + SCH 23,390 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL, i.t.) + SCH 23,390 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + L-741,626 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL, i.t.) + L-741,626 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + SCH 23,390 (5 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + LY 2,359,549 (5 ng/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + L-741,626 (5 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + SCH 23,390 (5 μg/20 μL, i.t.) + LY 2,359,549 (5 ng/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + L-741,626 (5 μg/20 μL, i.t.) + LY 2,359,549 (5 ng/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + PP2 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL, i.t.) + PP2 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + YM 254,890 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.); TCI + NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL, i.t.) + YM 254,890 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.). The experimental unit is the unit of experimental material which is randomly assigned to receive a treatment [22]. For each test, the experimental unit was an individual animal. And for behavioral test, n = 6 for each group, and for molecular test, n = 4 for each group. In experiments for behavior test and pharmacological studies, animals were randomized into treatment groups by picking numbers out of a hat. The investigators are blinded during the test.

Bone cancer pain induced by intra-tibial inoculation of Walker 256 cells

An intra-tibial bone cavity administration of Walker 256 mammary gland carcinoma cells was used to generate bone cancer pain [21]. Walker 256 mammary gland carcinoma cells were purchased from Cell Culture Center of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For this procedure, 0.5 mL Walker 256 cells (5 × 106 cells/mL) were intraperitoneally injected to rats weighting 60–80 g to result in ascites. The ascites containing more Walker 256 cells were removed from the abdominal cavities of the rats and centrifuged (450 g, 6 min). After washing 3 times with ice cold 0.01 M PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4), the cells were kept on ice at 1 × 105 cells/μL. Rats weighing 180–220 g were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.); after that, the hairs of the tibia were removed. The cells (1 × 105 cells/μL, 5 μL) were then injected into the tibia of the left leg. In the vehicle group, 5 μL PBS were injected instead. Finally, the bone wax and dental materials were used to plug the injection hole. Each rat was intramuscularly injected with 40,000 units penicillin for the prevention of infection.

Behavioral assays for pain

Before testing, rats were acclimated to the environment, and they were placed in separated clear plastic boxes for at least 15 min. Then, the hind paw of the rats was stimulated with Von Frey hairs (1.4–15 g) (Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, USA). A valid response was indicated by a quick licking or withdrawal of hind paw after Von Frey stimulation. The exact force that induced a positive response was recorded; if not, the next higher or lower Von Frey was applied. At least 3 positive responses were tested for each rat to obtain the average threshold.

Intrathecal injection method

The rat was anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.), and the fur around L4-L6 region of the spinal cord was shaved. The rat was placed in a prone position, and a stainless steel needle (30 gauge) was used for a lumbar puncture injection. The injection was conducted in the L4-L6 region of the spinal cord, and a tail flick accompanied a proper injection [23].

Primary cultures of spinal neurons

On the 13th day of pregnancy, the embryo was removed in a sterile environment, their spinal cords were separated and the meninges were removed according to previous research [7], [24]. Then, 0.15% trypsin was used to digest the spinal cords for 25 min at 37℃. After termination of the digestion, the spinal cords were centrifuged (4 min, 200 g). And the supernatant was removed and the sediment was resuspended in solution containing DNase and soybean trypsin inhibitor. Then, a solution containing MgCl2 and CaCl2 was added to the cells. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged (4 min, 200 g) at RT to obtain the cells 15 min later. The cells were resuspended with a neurobasal plating medium that contains 1% l-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were plated at of 2.5 × 106 cells/well onto 96-well clear-bottomed black plates that were pre-coated with 0.1 mg/mL PLL for 1.75–2 h.

Determination of intracellular Ca2+ concentration

The cells were incubated in 96-well plates with 4 μM fluo-8 (100 μL/well, diluted in warm Locke’s buffer (8.6 mM HEPES, 5.6 mM KCl, 5.6 mM D-Glucose, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 2.3 mM CaCl2, 154 mM NaCl, 0.0001 mM glycine, pH 7.4) at 37℃ for 1 h on the 9th day. Then, the dye buffer was replaced with warm (37℃) Locke’s buffer to wash 5 times. Finally, for the group that was given only one drug, 175 μL Locke’s buffer were left in each well, and for the group that received two drugs, 150 μL Locke’s buffer were finally left. Then, 25 μL of 8 × compounds were added to the corresponding cells. The first compound was added at 300 s after the fluorescence was measured with fluorescent imaging plate reader (FLIPR) (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and the second compound was added at the 600 s after the fluorescence was taken; after that, another 600 s is needed for further fluorescence reading [7].

Western blotting

In brief, after the rats were anesthetized, the spinal cords (L4-L6) of rats were removed out and were lysed with RIPA (50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate). Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels were used to separate the proteins according to their different molecular weights. After that, the proteins were transferred onto 0.22 μm polyvinylidenedifluoride membranes and incubated with different primary antibodies (1:1000) for 24 h at 4 ℃ and 3 h at RT after blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After the secondary antibodies (1:3000) were incubated at RT for approximately 2 h, the membranes were incubated with ECL reagents. The signals were detected and analyzed with Quantity One-4.6.5 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA), then divide the test proteins by GAPDH correspondingly and finally normalize it by the control protein.

Immunofluorescence

After the rats were anesthetized, they were perfused with 200 mL 0.01 M PBS and 200 mL 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After that, the spinal cords of the rats were collected and placed in the 4% PFA at 4 ℃ for another 24 h. Then, the spinal cords were dehydrated in 30% sucrose for 3–5 days until they sank to the bottom. After they were cut into 25 μm thick slices, they were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies after they were blocked with 10% donkey serum (containing 3‰ Triton-X-100). The signals were detected with laser-scanning microscopy (Carl Zeiss LSM700, Germany) and analyzed with Image Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Rabbit IgG was used as an isotype control. The expression of c-Fos was counted with its numbers in the field of the same size in the superficial layer (lamina I and II) of different groups.

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimation was determined by G*Power 3.1 [25] and the powers (1-β err prob) were greater than 0.9 which was sufficient to detect differences between two different groups. Data is analyzed by SPSS Rel 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software. Alteration of expression of the proteins detected and the behavioral responses were tested with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the differences in latency over time among groups were tested with two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests. The results are expressed as mean ± standard error, and the behavior test has been repeated for 3 times. Results described as significant are based on a criterion of P < 0.05 was considered significant. The amendments are highlighted using yellow highlights in the revised manuscript.

Results

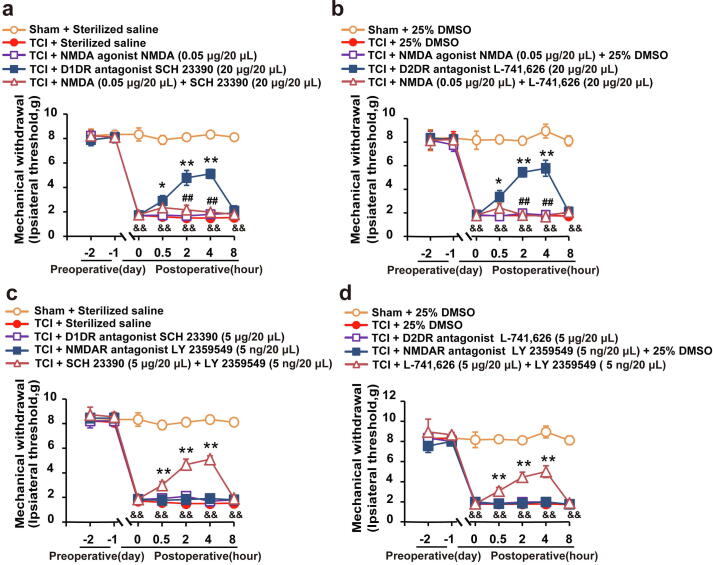

D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced antinociception in TCI rats was mediated by NMDAR

The behavior test was conducted on the 14th day after the transplantation of Walker 256 cells into the tibia bone. Herein, the intrathecal administration of the NMDAR agonist (0.05 μg/ 20 μL) was found to abolish both the D1DR antagonist SCH 23,390 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.) (Fig. 1a) and D2DR antagonist L-741,626 (20 μg/20 μL, i.t.) (Fig. 1b) production of antinociception in TCI rats. The intrathecal administration of the D1DR antagonist SCH 23,390 (5 μg/20 μL), D2DR antagonist L-741,626 (5 μg/20 μL) and NMDAR antagonist (5 ng/20 μL) had no effect on the thresholds of mechanical allodynia (Fig. 1c, d), while the combined administration of D1DR/D2DR antagonists (5 μg/20 μL) with NMDAR antagonist (5 ng/20 μL) could also attenuate TCI-induced bone cancer pain, which might suggest that D1DR/D2DR might exert antinociception synergistically with NMDAR.

Fig. 1.

The D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced antinociception in TCI rats was mediated by NMDAR. (a, b) The mechanical thresholds of TCI rats after coadministration of SCH 23390/L-741,626 with NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL, i.t.) (NMDA was administered 30 min before SCH 23390/L-741,626 treatment). (c, d) The mechanical thresholds of TCI rats after coadministration of SCH 23390/L-741,626 SCH 23,390 with LY359549 (n = 6, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with TCI + SCH 23390/L-741,626 group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with 0 h, &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, D1DR antagonist SCH 23390, D2DR antagonist L-741,626, NMDAR antagonist LY 359549, and NMDAR agonist NMDA, Vehicle: 25% DMSO).

D1DR/D2DR antagonists abolished NMDA-triggered Ca2+ up-regulation and inhibited the expression of p-NR1, p-NR2B in the spinal cord, and D1DR/D2DR antagonists induced inhibition of spinal neurons could be reversed by NMDA

The NMDA agonist NMDA (10 μM) was found to induce an obvious increase in Ca2+ oscillations, and the D1DR/D2DR antagonists (10 μM) could suppress the Ca2+ oscillations in spinal neurons (Fig. 2a, trace 2,3 and 4, Fig. 2b). Pretreatment with the D1DR/D2DR antagonists could suppress the NMDA induced up-regulation of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 2a, trace 5–6, Fig. 2b). Herein, the spinal inhibition of D1DR/D2DR with antagonists (20 μg/20 μL) was also found inhibited the expression of CGRP and c-Fos. Additionally, the intrathecal administration of NMDA could reverse the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of c-Fos and CGRP, suggesting that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of spinal neurons activation was mediated by NMDAR (Fig. 2f, g and h). It has been reported that NMDAR subunits, p-NR1 and NR2B were upregulated in chronic bone cancer pain, this article confirmed the upregulated expression of p-NR1 and p-NR2B in the spinal cord of TCI rats, and D1DR/D2DR antagonists could inhibit the upregulated p-NR1 and p-NR2B in the spinal cord (Fig. 2c, d and e).

Fig. 2.

D1DR/D2DR antagonists abolished NMDA-triggered Ca2+ up-regulation and inhibited the expression of p-NR1, p-NR2B in the spinal cord, and D1DR/D2DR antagonists induced inhibition of spinal neurons could be reversed by NMDA. (a, b) Representative traces and AUCs of SCH 23,390 (trace 2)/L-741,626 (10 μM) (trace 3), NMDA (trace 4) of the Ca2+ oscillations and the effect of SCH 23390/L-741,626 on NMDA (trace 5, 6)-induced upregulation of Ca2+ in spinal neurons (n = 3, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with Vehicle group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with NMDA group, Vehicle: Locke’s buffer). (c, d, e) The expression of p-NR1 and p-NR2B in TCI rats after administration of SCH 23,390 and L-741,626 (n = 4, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Vehicle group, p-NR1/NR1 is the expression of (p-NR1/GAPDH)/(NR1/GAPDH), p-NR2B/NR2B is the expression of (p-NR1/GAPDH)/(NR1/GAPDH)). (f, g, h) Immunofluorescence results indicated spinal CGRP and c-Fos expression in TCI rats after SCH 23390/L-741,626 was administrated for 2 h or after the coadministration of NMDA with SCH 23390/L-741,626, respectively (NMDA was administrated 15 min before SCH 23,390 or L-741,626) (n = 4, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Vehicle group, & P < 0.05, && P < 0.01, compared with TCI + SCH 23390/L-741,626 group).

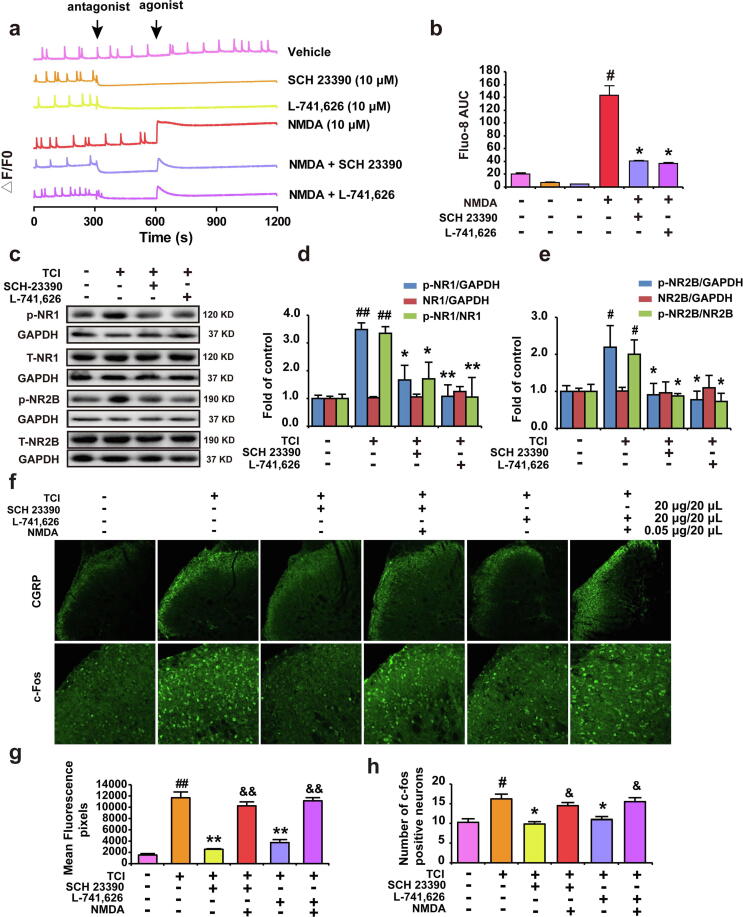

D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced down-regulation of phosphorylated MAPK expression could be reversed by NMDAR agonist

Intrathecal administration of the D1DR/D2DR antagonists (20 μg/20 μL) was confirmed to decrease spinal p-p38, p-JNK, and p-ERK1/2 expression in TCI rats. Herein, NMDA was also found could abolish the inhibitory effects of D1DR (Fig. 3a, b, and c) and D2DR antagonists (Fig. 3d, e and f) on the expression of p-ERK1/2, p-p38, and p-JNK, suggesting that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of spinal MAPKs was mediated by NMDAR.

Fig. 3.

D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced down-regulation of phosphorylated MAPKs expression could be reversed by NMDAR agonist. (a, b, and c) The expression of p-p38, p-ERK, and p-JNK in TCI rats after coadministration of SCH 23,390 with NMDA. (d, e, and f) The expression of p-p38, p-JNK, and p-ERK in TCI rats after coadministration of L-741,626 with NMDA (n = 4, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Vehicle group, & P < 0.05, && P < 0.01, compared with TCI + SCH 23390/L-741,626 group, p-MAPKs/MAPKs is the expression of (p- MAPKs/GAPDH)/(MAPKs/GAPDH)).

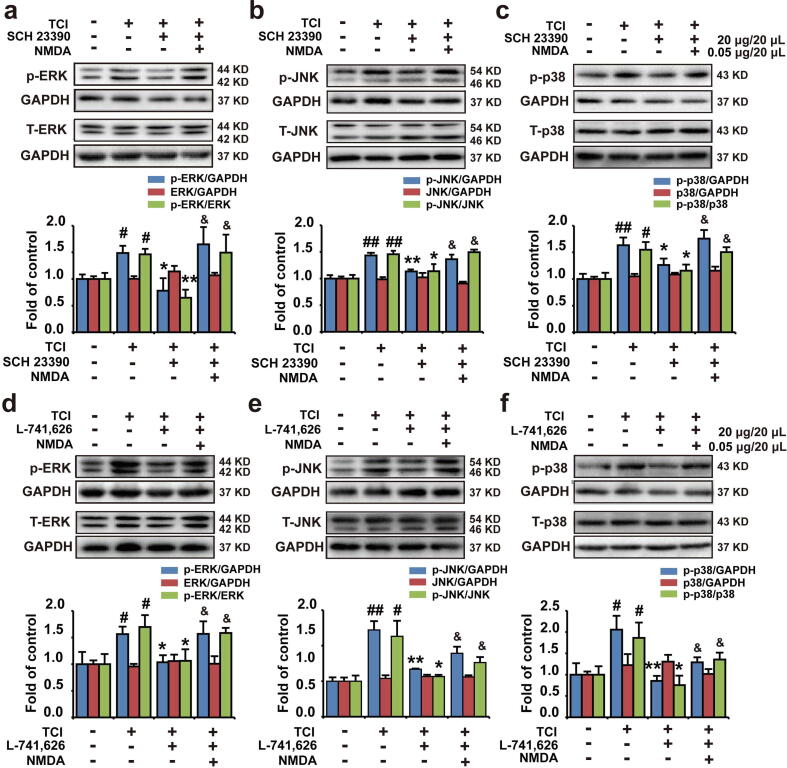

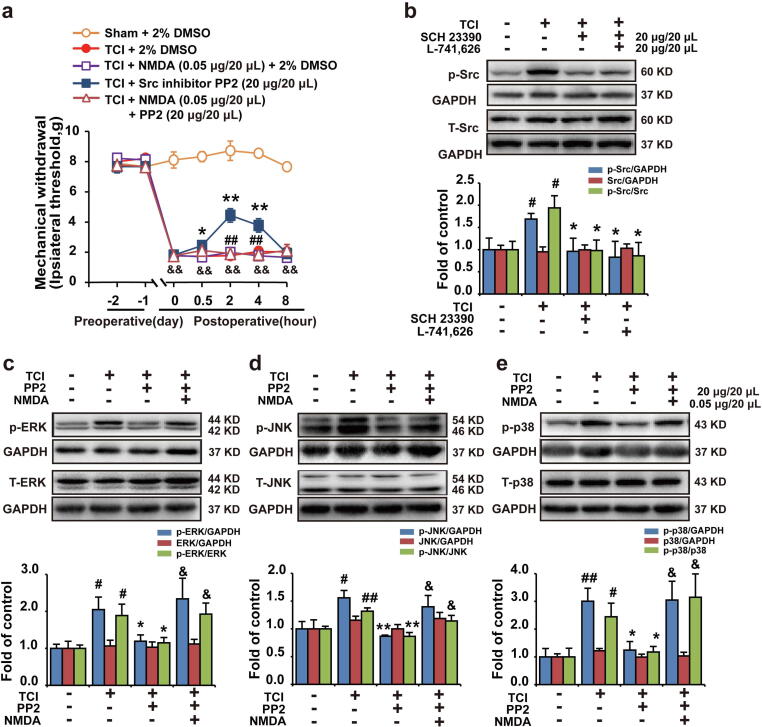

D1DR/D2DR antagonists inhibited Src to suppress NMDAR and downstream MAPKs to attenuate bone cancer pain

The D1DR/D2DR antagonists were found to suppress the expression of spinal p-Src in TCI rats (Fig. 4b). And an intrathecal injection of Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (20 μg/20 μL) could attenuate chronic bone cancer pain in TCI rats (Fig. 4a). PP2 was also found to inhibit the expression of spinal p-p38, p-JNK, and p-ERK1/2 in TCI rats (Fig. 4c, d, and e). In addition, intrathecal administration of NMDA could reverse PP2-induced antinociception and inhibition of spinal MAPKs in TCI rats.

Fig. 4.

D1DR/D2DR antagonists inhibited Src to suppress NMDAR and downstream MAPKs to attenuate bone cancer pain. (a) The mechanical thresholds of TCI rats after administration of Src inhibitor PP2 or coadministration of Src inhibitor PP2 with NMDA (n = 6, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with 0 h, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Src inhibitor group, & P < 0.05, && P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, Vehicle: 2% DMSO) (NMDA was administered 30 min before PP2 treatment). (b) The p-Src expression in TCI rats after administration of SCH 23390/L-741,626. (c, d, e) The p-p38, p-ERK, and p-JNK expression in TCI rats after coadministration of Src inhibitor PP2 with NMDA. (n = 4, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with control group, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Vehicle group, & P < 0.05, && P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Src inhibitor group, p-Src/Src is the expression of (p-Src/GAPDH)/(Src/GAPDH), p-MAPKs/MAPKs is the expression of (p- MAPKs/GAPDH)/(MAPKs/GAPDH)).

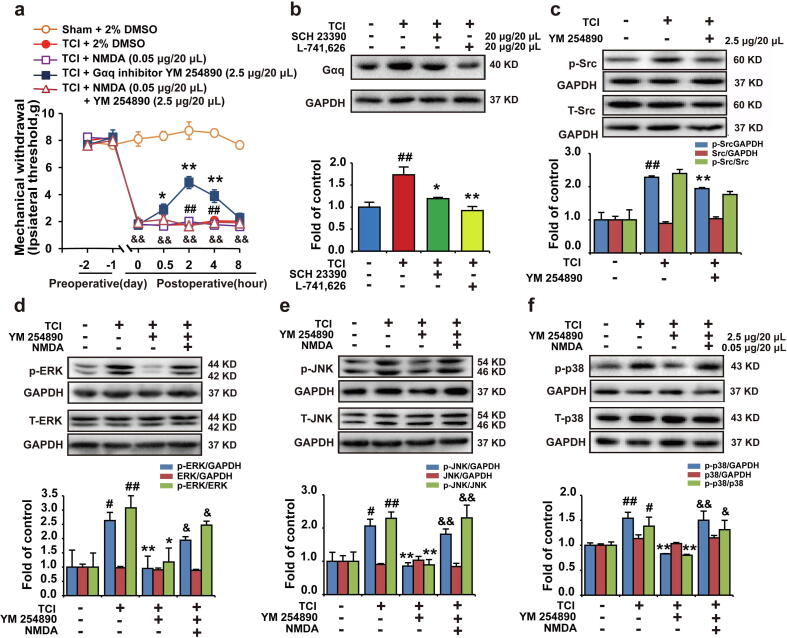

D1DR/D2DR activated NMDAR-MAPKs to promote bone cancer pain through Src kinase in a Gαq protein-dependent manner

This research found that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists could also inhibit the expression of Gαq protein (Fig. 5b). The intrathecal administration of the Gαq inhibitor YM 254,890 could attenuate TCI-induced bone cancer pain (Fig. 5a) and inhibit p-JNK, p-p38, p-ERK1/2 expresison in TCI rats, which could both be reversed by NMDA (0.05 μg/20 μL) (Fig. 5d, e, f). Additionally, further results indicated that Gαq inhibitor YM 254,890 also suppressed the expression of p-Src (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

D1DR/D2DR activated NMDAR-MAPKs to promote bone cancer pain through Src in a Gαq protein-dependent manner. (a) The mechanical thresholds of TCI rats after administration of Gαq inhibitor YM 254,890 or co-administration of YM 254,890 with NMDA (n = 6, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with 0 h, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Gαq inhibitor group, &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, Vehicle: 2% DMSO) (NMDA was administered 30 min before PP2 treatment). (b) Gαq protein expression in TCI rats after administration of SCH 23390/L-741,626. (c) p-Src expression in TCI rats after administration of Gαq inhibitor YM 254890. (d, e, f) The expression of p-p38, p-ERK, and p-JNK in TCI rats after co-administration of the Gαq inhibitor YM 254,890 with NMDA. (n = 4, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, compared with Sham + Vehicle group, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with TCI group, &P < 0.05, && P < 0.01, compared with TCI + Gαq inhibitor group, p-Src/Src is the expression of (p-Src/GAPDH)/(Src/GAPDH), p-MAPKs/MAPKs is the expression of (p- MAPKs/GAPDH)/(MAPKs/GAPDH)).

Discussion

This article indicated that (1) D1DR/D2DR antagonists could inhibit the NMDAR-induced Ca2+ upregulation in spinal primary cultures neurons; (2) the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of activated spinal neurons in TCI rats was mediated by NMDA; (3) D1DR/D2DR antagonists could inhibit NMDAR mediated spinal neurons activation to alleviate bone cancer pain in TCI rats through Src kinase in a Gαq-dependent manner.

NMDAR is vital in chronic pain, and spinal NMDAR inhibition was reported to attenuate bone cancer pain [7]. NMDAR antagonists such as ketamine and MK801 have been used in clinical practice; however, their severe side effects limit their clinical use [8], [9]. The modulation of NMDAR by dopamine receptors has been reported in different parts of brain. D1DR activation might increase NMDAR activities in a Gαs dependent manner through the cAMP/ PKA pathways in different brain regions [10], [11], [12]. D1DR activation also increased NMDAR function in acutely isolated PFC pyramidal neurons via protein kinase C (PKC) activation [26]. However, D1DR activation also could inhibit NMDAR by a direct protein–protein interaction [27] or through Src tyrosine kinase inhibition in a G protein-independent manner [28]. In contrast to the enhancing effect of D1DR on NMDAR mediated responses, D2DR activation might lead to the inhibition of NMDAR function in the brain [13]. The mechanism might be through the inhibition of cAMP production through the Gαi protein. However, the effects and mechanisms of D1DR and D2DR in the modulation of NMDAR in chronic pain have not been explored.

It has been reported that a change in Ca2+ concentration is important in the regulation of the plasticity of neurons [29]. The activation of NMDAR has been reported to induce an obvious upregulation in Ca2+ oscillations to increase the sensitivity of spinal neurons and promote chronic pain [7], [8]. This research indicated that the administration of NMDA could induce an obvious rise in Ca2+ concentration in spinal neurons, and both D1DR and D2DR antagonists could decrease the NMDA-induced upregulation of Ca2+ oscillations in spinal neurons. In addition, c-Fos and CGRP, which are markers of spinal neurons [30], [31], were upregulated in the spinal cord, indicating the activation of spinal neurons in TCI rats. The D1DR/D2DR antagonists could suppress the expression of CGRP and c-Fos, which could be reversed by NMDA, indicating that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of spinal neurons was mediated by NMDA in TCI rats. The subunits of NMDAR, p-NR1 and p-NR2B which have been reported to play an important role in bone cancer pain [32], [33] also were detected. It turned out that D1DR/D2DR antagonists both could inhibit the upregulated p-NR1 and p-NR2B in the spinal cord of TCI rats. Although D1DR/D2DR antagonists were found could inhibited the upregulated expression of NMDA subunits p-NR1 and p-NR2B, the way of D1DR/D2DR affected NMDA function and the specific assemnlies of NMDA subunits regulated by D1DR/D2DR also need further exploration. Further in vivo results indicated that the intrathecal administration of D1DR/D2DR antagonists induced the attenuation of bone cancer pain could be reversed by NMDA indicating that blocking the NMDAR does unmask the analgesic effect of inhibition of D1 or D2 receptors. Additionally, the combined administration of the D1DR/D2DR antagonists with a NMDAR antagonist at nonanalgesic doses could remit the bone cancer pain that was induced by TCI. These results suggested that D1DR/D2DR agonists might activate NMDAR to promote chronic bone cancer pain.

Our previous research indicated that in TCI rats, D1DR and D2DR could form heterodimers in the spinal cord that in turn couple to Gαq protein (unpublished data). Furthermore, the activation of Gαq-coupled receptors could enhance NMDAR function [16], [17]. It has been reported that the activation of Gαq-coupled receptors in brain, such as the metabotropic glutamate receptors 5 (mGlu5) [34], and pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide (PACAP) [16] could enhance NMDAR-mediated function via PKC/cellular adhesion kinase β (CAKβ)/Src signaling. The activation of Gαq could also activate NMDAR via proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2)/CAKβ/Src signaling in a PKC-independent manner [35]. The activation of Gαq coupled receptor postsynaptic adenosine A2A receptor could activate the G protein/Src pathway to increase NMDAR function [36]. Herein, D1DR/D2DR antagonists inhibited the expression of Gαq protein and that the Gαq inhibitor-induced antinociception could be reversed by NMDAR agonists, which suggested that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of NMDAR was mediated by Gαq protein. However, Gαq protein was also found could promote the Ca2+ release from intracellular stores to elevate cytosolic Ca2+ which also could promote the development of chronic bone cancer pain. So D1DR and D2DR were supposed that could on one side active Gαq to directly active spinal neurons and on the other side to activate NMDAR to activate spinal neurons to promote chronic bone cancer pain.

Src kinase is part of the NMDAR complexes in neurons and could phosphorylate NMDAR to activate NMDA [37]. GPCR ligands like muscarine and lysophosphatidic acid have been reported to potentiate NMDAR function and trafficking by activating Src kinase [17]. Additionally, D1DR was also reported to modulate NMDAR function through Src [38]. Inhibiting Src has been reported could attenuate TCI induced bone cancer pain. Oral gavage with Src inhibitor Saracatinib [39], [40], dasatinib [19] could attenuate intra-tibial injection of rat mammary cancer cells induced bone cancer pain, and PP2 was also reported could reduce cancer metastasis [41], [42]. Herein, D1DR/D2DR antagonists and Gαq inhibitors were also found could inhibit spinal p-Src expression. Furthermore, the Src inhibitor induced attenuation of chronic bone cancer pain could be reversed by an NMDAR agonist. These results suggested that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of NMDAR function was mediated by Src kinase.

The activation of NMDAR has been reported to increase Ca2+ oscillations in spinal neurons, which could activate calcium-regulated proteins like MAPKs, which include p-p38, p-ERK1/2, and p-JNK, to further activate spinal neurons in TCI rats [7]. This research indicated that the spinal injection of D1DR/D2DR antagonists, Src kinase and Gαq protein inhibitor could inhibit spinal p-JNK, p-p38, and p-ERK1/2 expression, while the NMDAR agonist could reverse this inhibition. These results indicated that MAPKs may be the downstream effectors of NMDAR of D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced analgesia in TCI rats.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the inhibition of spinal D1DR/D2DR could decrease the NMDAR-mediated activation of spinal neurons to remit bone cancer pain induced by TCI. Further results indicated that the D1DR/D2DR antagonists-induced inhibition of NMDAR function in spinal neurons was mediated by Gαq protein and Src kinase in TCI rats. This result may provide a new mechanism of bone cancer pain and suggests that D1DR/D2DR could be therapeutic targets to alleviate chronic pain, and they might reduce the side effects of NMDAR antagonist in chronic bone cancer pain.

Compliance with Ethics requirements

The study was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University and performed in accordance with the Interdisciplinary Principles and Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research, Testing, and Education issued by the New York Academy of Sciences Adhoc Committee on Animal Research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation Youth Fund project (Grant number, 81803752); “Double First-Class” University project (Grant number, CPU2018GY32, CPU2018GF06); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation program (Grant number, 1600020009); China Postdoctoral Special Funding program (Grant number, 1601900013).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2020.08.005.

Contributor Information

Bo-Yang Yu, Email: boyangyu59@163.com.

Ji-Hua Liu, Email: liujihua@cpu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kane C.M., Hoskin P., Bennett M.I. Cancer induced bone pain. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman R.E. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–6249s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantyh P.W., Clohisy D.R., Koltzenburg M., Hunt S.P. Molecular mechanisms of cancer pain. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:201–209. doi: 10.1038/nrc747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantyh P. Bone cancer pain: causes, consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. Pain. 2013;154(Suppl 1):S54–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelamangalath L., Dravid S.M., George J., Aldrich J.V., Murray T.F. kappa-Opioid receptor inhibition of calcium oscillations in spinal cord neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:1061–1071. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen K.B., Yi F., Perszyk R.E., Menniti F.S., Traynelis S.F. NMDA Receptors in the Central Nervous System. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1677:1–80. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7321-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai W.L., Yan B., Jiang N., Wu J.J., Liu X.F., Liu J.H. Simultaneous inhibition of NMDA and mGlu1/5 receptors by levo-corydalmine in rat spinal cord attenuates bone cancer pain. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;141:805–815. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleakman D., Alt A., Nisenbaum E.S. Glutamate receptors and pain. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bredlau A.L., Thakur R., Korones D.N., Dworkin R.H. Ketamine for pain in adults and children with cancer: a systematic review and synthesis of the literature. Pain Med. 2013;14:1505–1517. doi: 10.1111/pme.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stramiello M., Wagner J.J. D1/5 receptor-mediated enhancement of LTP requires PKA, Src family kinases, and NR2B-containing NMDARs. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder G.L., Fienberg A.A., Huganir R.L., Greengard P. A dopamine/D1 receptor/protein kinase A/dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein (Mr 32 kDa)/protein phosphatase-1 pathway regulates dephosphorylation of the NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10297–10303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10297.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuchi M., Tabuchi A., Kuwana Y., Watanabe S., Inoue M., Takasaki I. Neuromodulatory effect of Galphas- or Galphaq-coupled G-protein-coupled receptor on NMDA receptor selectively activates the NMDA receptor/Ca2+/calcineurin/cAMP response element-binding protein-regulated transcriptional coactivator 1 pathway to effectively induce brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in neurons. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5606–5624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3650-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cepeda C., Buchwald N.A., Levine M.S. Neuromodulatory actions of dopamine in the neostriatum are dependent upon the excitatory amino acid receptor subtypes activated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1993;90:9576–9580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaulieu J.M., Gainetdinov R.R. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:182–217. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasbi A., Fan T., Alijaniaram M., Nguyen T., Perreault M.L., O'Dowd B.F. Calcium signaling cascade links dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer to striatal BDNF production and neuronal growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:21377–21382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903676106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macdonald D.S., Weerapura M., Beazely M.A., Martin L., Czerwinski W., Roder J.C. Modulation of NMDA receptors by pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide in CA1 neurons requires G alpha q, protein kinase C, and activation of Src. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11374–11384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3871-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W.Y., Xiong Z.G., Lei S., Orser B.A., Dudek E., Browning M.D. G-protein-coupled receptors act via protein kinase C and Src to regulate NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:331–338. doi: 10.1038/7243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salter M.W., Pitcher G.M. Dysregulated Src upregulation of NMDA receptor activity: a common link in chronic pain and schizophrenia. FEBS J. 2012;279:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appel C.K., Gallego-Pedersen S., Andersen L., Blancheflor Kristensen S., Ding M., Falk S. The Src family kinase inhibitor dasatinib delays pain-related behaviour and conserves bone in a rat model of cancer-induced bone pain. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4792. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shenoy P.A., Kuo A., Vetter I., Smith M.T. The Walker 256 Breast Cancer Cell- Induced Bone Pain Model in Rats. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:286. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao-Ying Q.L., Zhao J., Dong Z.Q., Wang J., Yu J., Yan M.F. A rat model of bone cancer pain induced by intra-tibia inoculation of Walker 256 mammary gland carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1292–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Festing M.F., Altman D.G. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 2002;43:244–258. doi: 10.1093/ilar.43.4.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Njoo C., Heinl C., Kuner R. In Vivo SiRNA Transfection and Gene Knockdown in Spinal Cord via Rapid Noninvasive Lumbar Intrathecal Injections in Mice. Journal of visualized experiments: JOVE. 2014 doi: 10.3791/51229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langlois S.D., Morin S., Yam P.T., Charron F. Dissection and culture of commissural neurons from embryonic spinal cord. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2010 doi: 10.3791/1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faul F., Erdfelder E., Buchner A., Lang A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y.C., Liu G., Hu J.L., Gao W.J., Huang Y.Q. Dopamine D(1) receptor-mediated enhancement of NMDA receptor trafficking requires rapid PKC-dependent synaptic insertion in the prefrontal neurons. J Neurochem. 2010;114:62–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee F.J., Xue S., Pei L., Vukusic B., Chery N., Wang Y. Dual regulation of NMDA receptor functions by direct protein-protein interactions with the dopamine D1 receptor. Cell. 2002;111:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong H., Gibb A.J. Dopamine D1 receptor inhibition of NMDA receptor currents mediated by tyrosine kinase-dependent receptor trafficking in neonatal rat striatum. J Physiol. 2008;586:4693–4707. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.158931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer N.C., Olson E., Gu X. Spontaneous calcium transients regulate neuronal plasticity in developing neurons. J Neurobiol. 1995;26:316–324. doi: 10.1002/neu.480260304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos P.L., Brito R.G., Matos J., Quintans J.S.S., Quintans-Junior L.J. Fos Protein as a Marker of Neuronal Activity: a Useful Tool in the Study of the Mechanism of Action of Natural Products with Analgesic Activity. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:4560–4579. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalin S., Miller K.R., Kalin R.E., Jendrach M., Witzel C., Heppner F.L. CNS myeloid cells critically regulate heat hyperalgesia. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128:2774–2786. doi: 10.1172/JCI95305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S., Liu W.T., Liu Y.P., Dong H.L., Henkemeyer M., Xiong L.Z. Blocking EphB1 receptor forward signaling in spinal cord relieves bone cancer pain and rescues analgesic effect of morphine treatment in rodents. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4392–4402. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu S., Wang C., Han Y., Song C., Hu X., Liu Y. Sigma-1 Receptor Antagonist BD1047 Reduces Mechanical Allodynia in a Rat Model of Bone Cancer Pain through the Inhibition of Spinal NR1 Phosphorylation and Microglia Activation. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/265056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotecha S.A., Jackson M.F., Al-Mahrouki A., Roder J.C., Orser B.A., MacDonald J.F. Co-stimulation of mGluR5 and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors is required for potentiation of excitatory synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27742–27749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heidinger V., Manzerra P., Wang X.Q., Strasser U., Yu S.P., Choi D.W. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1-induced upregulation of NMDA receptor current: mediation through the Pyk2/Src-family kinase pathway in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5452–5461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05452.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebola N., Lujan R., Cunha R.A., Mulle C. Adenosine A2A receptors are essential for long-term potentiation of NMDA-EPSCs at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2008;57:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salter M.W., Kalia L.V. Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1038/nrn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Socodato R., Santiago F.N., Portugal C.C., Domith I., Encarnacao T.G., Loiola E.C. Dopamine promotes NMDA receptor hypofunction in the retina through D1 receptor-mediated Csk activation, Src inhibition and decrease of GluN2B phosphorylation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40912. doi: 10.1038/srep40912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Felice M., Lambert D., Holen I., Escott K.J., Andrew D. Effects of Src-kinase inhibition in cancer-induced bone pain. Mol. Pain. 2016;12 doi: 10.1177/1744806916643725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danson S., Mulvey M.R., Turner L., Horsman J., Escott K., Coleman R.E. An exploratory randomized-controlled trial of the efficacy of the Src-kinase inhibitor saracatinib as a novel analgesic for cancer-induced bone pain. J. Bone Onco. 2019;19 doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2019.100261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nam J.S.I.Y., Sakamoto M., Hirohashi S. Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 restores the E-cadherin/catenin cell adhesion system in human cancer cells and reduces cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fizazi K. The role of Src in prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1765–1773. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.