The spillover of the coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 placed the relationship between humans and wildlife under a global spotlight. The subsequent fallout of the COVID‐19 pandemic is now affecting wild animal populations and habitats through multiple pathways, with feedbacks that further impact human health and livelihoods. By disentangling these complex and interacting pathways, we can better understand the socio‐ecological dynamics linking the people, wildlife, and ecosystems experiencing this shock. Such an understanding will facilitate the development and implementation of more effective responses to the current crisis, in part by informing the design of targeted policy interventions.

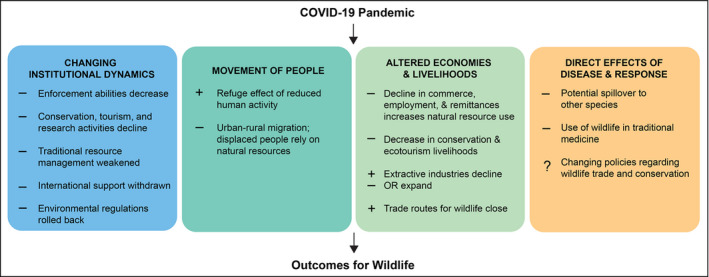

In a study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (Gaynor et al. 2016), we developed a framework for understanding how armed conflict affects wildlife populations and habitats through myriad pathways. While producing a range of unique environmentally destructive outcomes, armed conflicts can also create dynamics similar to those which have been seen during the COVID‐19 pandemic: namely, profound disruptions to human communities, wildlife populations, and their interconnections. Here, we revisit our findings on these pathways, emphasizing relevant analogs and lessons that may be transferrable from war to the current COVID‐19 pandemic, including the limitations of pathways leading to positive wildlife outcomes, concerns regarding weakened institutional support, and impacts of shifting wildlife use (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diverse pathways link the COVID‐19 pandemic, and its political, economic, and social fallout, to outcomes for wildlife. While some pathways benefit wildlife (+), most have detrimental consequences (–). Adapted from Gaynor et al. (2016).

Positive outcomes of the COVID‐19 pandemic for wildlife may occur when people cease their normal activities, as wild animals often flourish in areas that people avoid. This “refuge effect” has been documented in areas of armed conflict, such as North Korea's demilitarized zone (Kim 1997). During the current pandemic, media accounts have documented cases of increased wildlife activity in national parks and urban green spaces as people have remained indoors (Zellmer et al. 2020), and there is evidence of reductions in wildlife–vehicle collisions in several states in the US (Nguyen et al. 2020). However, as we found in the case of armed conflict, the effects of the pandemic's widespread institutional, social, and economic disruption on wildlife are likely to be overwhelmingly negative in most contexts. While benefits to wildlife are often transient, many of these negative impacts can persist over extensive temporal and geographic scales, compounded by interactions across pathways.

The COVID‐19 pandemic is already weakening institutional support for conservation by interrupting funding streams, eroding protection of parks and vulnerable species, and forestalling vital monitoring and research activities that make these impacts visible (Lindsey et al. 2020). As people reduce activity (including travel) to avoid or minimize transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2, reductions in tourism have led to critical revenue losses for parks around the world (Knorovsky 2020), and reductions in enforcement and human presence in protected areas have contributed to a rise in illegal activities like logging and hunting (Humphrey 2020). Conservation efforts may be further hampered by the economic downturn and associated withdrawal of governmental and philanthropic financial support, alongside the weakening and dismantling of environmental regulations under the guise of economic recovery (Davenport and Friedman 2020; Gonzales 2020). In our 2016 study, this weakening of conservation institutions represented the most important set of pathways linking armed conflict to wildlife, leading to marked wartime declines in animal populations (Daskin and Pringle 2018). The pandemic has reiterated – in the starkest terms – the lessons learned from previous catastrophes, including armed conflict: conservation and natural resource management efforts that invest in locally managed institutions are best situated to mitigate the negative impacts of the pandemic and foster resilience to future shocks.

Patterns of human migration and economic disruption associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic are also likely to shift patterns of natural resource use, as observed in wartime (Gaynor et al. 2016). The pandemic and associated lockdowns have precipitated an exodus of urban populations to rural areas (Srivastava and Nagaraj 2020; Yacila and Turkewitz 2020), widespread job losses and declines in remittances, and disruption of food systems at multiple scales (Gunia 2020). The resulting economic and food insecurity, compounded by weakened enforcement of anti‐poaching laws and interruptions in domestic meat supply chains, is likely to increase local demand for wild meat (Bowlin 2020), as found among people affected by armed conflict. While many policies proposed to forestall future pandemics seek to limit wildlife consumption (Yang et al. 2020), sweeping criminalization of the sale and consumption of wild meat may harm vulnerable human populations and weaken trust in institutions, as observed in West Africa after the 2013–2016 Ebola outbreak (Bonwitt et al. 2018). Policies that also provide food and livelihood alternatives, rather than primarily criminalizing consumers of wild meat, will likely be more effective and equitable than universal bans.

As we have seen after devastating armed conflicts, governments and other institutions now face difficult decisions about how to simultaneously promote economic recovery and public health. While conservation and environmental regulation may take a backseat, decision makers must remember that biodiversity and ecosystem health are closely tied to human well‐being, and deprioritizing conservation may ultimately heighten socioeconomic woes (Brashares et al. 2014). Instead, decision makers and the public can choose to transform this disruption into a catalyst for major policy reforms that promote the well‐being of people and wildlife, such as strengthening localized food supply chains and bottom‐up conservation efforts and institutions (Evans et al. 2020), which have proven successful in post‐conflict scenarios (Bruch et al. 2016). As the pandemic continues to unfold, highlighting the pathways through which it is affecting wildlife and habitats may inform more holistic and context‐dependent approaches to recovery that address the interlinked health of wildlife and people.

Front Ecol Environ 2020; 18(10):542–543, 10.1002/fee.2275

References

- Bonwitt J, Dawson M, Kandeh M, et al 2018. Unintended consequences of the “bushmeat ban” in West Africa during the 2013–2016 Ebola virus disease epidemic. Soc Sci Med 200: 166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin N. 2020. Hunting and fishing provide food security in the time of COVID‐19. High Country News 29 Apr. [Google Scholar]

- Brashares JS, Abrahms BA, Fiorella KJ, et al 2014. Wildlife declines and social conflict. Science 25: 376–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch C, Muffett C, and Nichols S. (Eds). 2016. Governance, natural resources and post‐conflict peacebuilding. London, UK: Routledge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daskin JH and Pringle RM. 2018. Warfare and wildlife declines in Africa's protected areas. Nature 553: 328–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport C and Friedman L. 2020. Trump, citing pandemic, moves to weaken two key environmental protections. New York Times 4 Jun. [Google Scholar]

- Evans KL, Ewen JG, Guillera‐Arroitra G, et al 2020. Conservation in the maelstrom of COVID‐19 – a call to action to solve the challenges, exploit opportunities and prepare for the next pandemic. Anim Conserv 23: 235–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor KM, Fiorella KJ, Gregory GH, et al 2016. War and wildlife: linking armed conflict to conservation. Front Ecol Environ 14: 533–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales J. 2020. Brazil minister advises using COVID‐19 to distract from Amazon deregulation. Mongabay Environmental News 26 May. [Google Scholar]

- Gunia A. 2020. How coronavirus is exposing the world's fragile food supply chain – and could leave millions hungry. Time 8 May. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey C. 2020. Under cover of COVID‐19, loggers plunder Cambodian wildlife sanctuary. Mongabay Environmental News 31 Aug. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC. 1997. Preserving biodiversity in Korea's demilitarized zone. Science 278: 242–43. [Google Scholar]

- Knorovsky K. 2020. Madagascar's tourism drought could fuel another crisis. National Geographic 20 May. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey P, Allan J, Brehony P, et al 2020. Conserving Africa's wildlife and wildlands through the COVID‐19 crisis and beyond. Nat Ecol Evol; 10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Saleh M, Kyaw MK, et al 2020. Special report 4: impact of COVID‐19 mitigation on wildlife–vehicle conflict. Davis, CA: Road Ecology Center, University of California–Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R and Nagaraj A. 2020. No way back: Indian workers shun city jobs after lockdown ordeal. Thomson Reuters Foundation News 28 May. [Google Scholar]

- Yacila RC and Turkewitz J. 2020. Highways of Peru swell with families fleeing virus. New York Times 30 Apr. [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Liu P, Li W, and Zhang L. 2020. Permanently ban wildlife consumption. Science 367: 1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellmer AJ, Wood EM, Surasinghe T, et al 2020. What can we learn from wildlife sightings during the COVID‐19 global shutdown? Ecosphere 11: e03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]