In a recent Gruppo Italiano Malattie EMatologiche dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) survey published in Leukemia, most Italian haematologists declared to have temporarily adopted telephone or video consultations in patients with Philadelphia‐negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. They also shared a certain propensity to expand the use of telemedicine after pandemic resolution. 1 MPNs includes essential thrombocythaemia (ET), polycythaemia vera (PV) and myelofibrosis (MF), and are chronic cancers with increased infectious risk compared to the normal population. 2 , 3 Analogously, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an auto‐immune disorder that may require prolonged and severe immunosuppressive therapy. 4 During the pandemic, the indication to move outpatient clinics to telephone‐ or video‐conferencing appointments was suggested in MPN or ITP. 5 , 6 , 7

To reduce the inflow of patients and the risk of contagion at our Centre during the pandemic, we developed a telemedicine project that switched specific patients from in‐person visits to telephone appointments, performed by haematologists who already knew the patients. The Hospital Information Technology (IT) system was rapidly implemented to record in‐person and telephone visits.

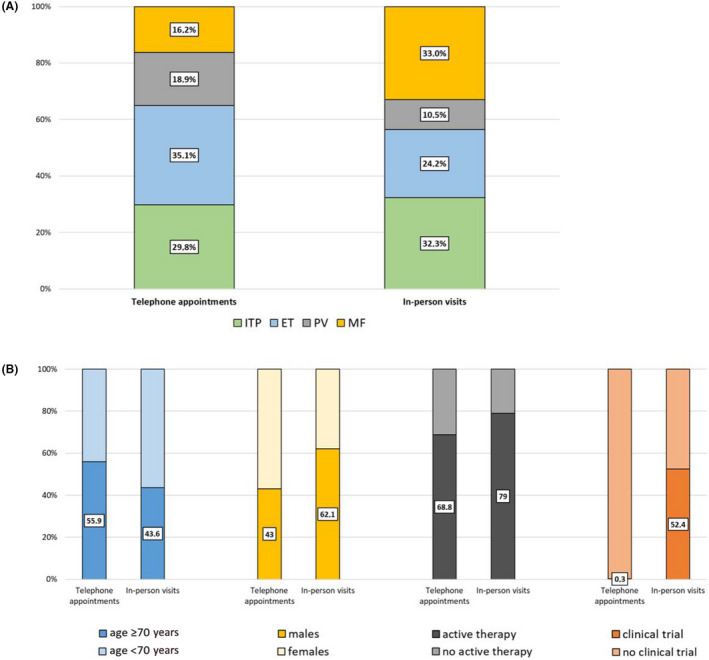

Between 9 March and 4 May 2020, 489 haematological visits were planned for ITP (30·5%), ET (32·3%), PV (16·8%) and MF (20·4%). In 349 (71·4%) visits, patients were under active pharmacological therapy for their disease, and in 66 (13·5%) visits, patients were enrolled into an investigational clinical trial. A total of 365 (74·6%) visits were converted to telephone appointments. Compared to patients receiving a telephone contact, the patients who required in‐person visits were more frequently affected by MF (P < 0·001), were under active therapy (P = 0·03) and enrolled into a clinical trial (P < 0·001). Also, these patients were more frequently males (P = 0·001) and younger (median age: 67 vs. 72 years, P = 0·006) Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Percentages of patients who received telephone appointments or in‐person visits stratified by type of haematological disease (A) or categorised according to patients’ and treatments’ characteristics (B). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To explore the level of satisfaction of patients towards telemedicine, we developed a 16‐questions questionnaire. Patients could score each question from 0 (total disagreement) to 10 (total agreement); answers were finally grouped in two categories (low–intermediate or high agreement, score 0–6 and 7–10 respectively).

Overall, 87 (23·8%) of the 365 patients who were involved in the telemedicine project responded to the satisfaction questionnaire Table S1. Questions were clustered into four groups according to their main focus: (i) adequacy of medical care (questions 1–5); (ii) psychological impact of telemedicine (questions 6–10); (iii) adequacy of IT system (questions 11–12); (iv) possible advantages and future use of telemedicine (questions 13–16). Within each cluster of questions, responses showed an overall high internal consistency and significance of correlation coefficients Table S2.

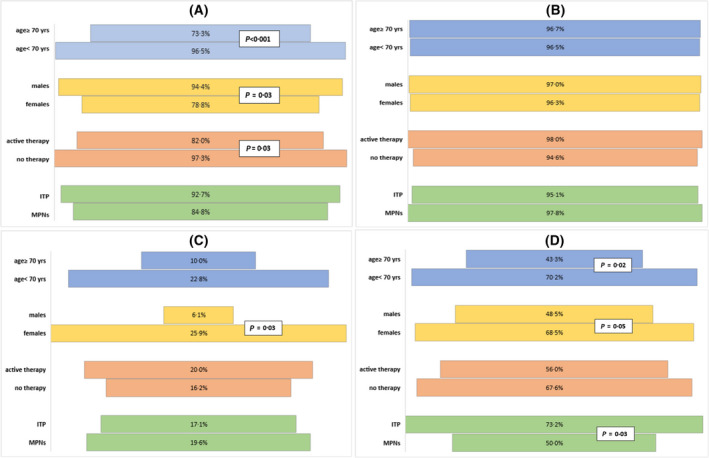

Concerning the adequacy of medical care (questions 1–4), the questionnaire showed a good degree of satisfaction of the respondents, with a score of ≥7 in 88·5% of the cases. However, the percentage of patients with high scores was significantly lower in the elderly (P = 0·001) and in males (P = 0·03) Fig 2A. Conversely, question 5, that investigated the relevance of the lack of physical contact, obtained low levels of agreement regardless of age, sex, type of therapy and disease Table S1. Notably, most patients used high scores also to describe their psychological experience during the telephone visit, indicating an overall good emotional acceptance of telemedicine Fig 2B. The use of video calls was of little relevance for most patients. However, the implementation of secure IT networks for rapid sharing of laboratory tests was indicated as a strategic asset to facilitate telemedicine, particularly by females Fig 2C. Finally, there were significant differences in the willingness to continue with telephone visits between elderly and younger patients (P = 0·02) and between male and female patients (P = 0·05). Most importantly, the continuation of telemedicine was better embraced by patients with ITP than by patients with MPNs (P = 0·03) Fig 2D. Among the latter, patients with MF showed the least appreciation of telemedicine as a routine mode of haematological evaluation, with only 33·3% of patients assigning high scores, compared to 41·2% and 65% of patients with PV and ET respectively.

Fig 2.

Percentage of patients who were assigned high (≥7) scores according to main patient and disease characteristics. Responses are shown for each cluster. Cluster 1: adequacy of medical care (A); cluster 2: psychological impact of telemedicine (B); cluster 3: adequacy of information technology system (C); cluster 4: possible advantages and future use of telemedicine (D). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The COVID‐19 pandemic highlighted how healthcare facilities can spread the virus, and focussed attention on new models of care that reduce in‐person contacts. 8 , 9 We converted more than 75% of the visits into telephone contacts, that were reserved for patients with active and/or resistant disease, particularly MF, and for patients enrolled into investigational clinical trials. To date, no complaint has been raised from patients involved in the telemedicine project, and no COVID‐19 infection has originated within our Centre.

Although telemedicine resulted in an overall good level of patients’ satisfaction, the lack of physical interaction was perceived as a strong limitation by all patients, emphasising how much haematological care moves beyond the technical evaluation of blood tests, and instead involves a global patient–doctor relationship. Patients who were more critical of telemedicine were typically older, possibly due to a greater difficulty in adopting innovations and in managing IT tools. Also, we observed gender‐based specificities, with female patients showing a lower appreciation of telemedicine, a greater need of IT tools improvement, and a reduced willingness to continue telemedicine beyond the pandemic. Whether this finding depends on a higher propensity of women to express their complaints, or a different female sensitivity to the patient–doctor relationship, remains to be clarified.

Compared to ITP, we found that patients with MPN (particularly, MF), were less eager to reduce in‐person visits in the future, and gave very little consideration to the economic, work and time benefits of telemedicine. This difference reflects the increased physical and psychological impact exerted by neoplastic (MPNs) compared to non‐neoplastic (ITP) diseases and also how the disease burden is different among MPNs. 10

The success of the telemedicine project during the COVID‐19 at out Institution was probably linked to multiple factors, including a rapid implementation of internal procedures, the presence of a dedicated medical team, and the nature of these diseases, characterised by a chronic course and outpatient care. Whether this experience may pave the way for a future expansion of telemedicine will have to be evaluated in a multidisciplinary way, taking into account not only the quality of medical care, but also the implementation of healthcare IT tools, the protection of medical‐legal aspects, patients consent, and the satisfaction with the patient–doctor relationship.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Table S1. Questionnaire of satisfaction that was responded to by 87 patients who were included in the telemedicine project during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The questionnaire was administered to patients by telephone, by health professionals who were not directly involved in the haematological management.

Table S2. Correlation matrices. The two values reported in the cells are, respectively, the pairwise correlation coefficients between the attribution of high scores of the corresponding questions of each cluster and the significance level of each correlation coefficient. Q, question.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana contro Leucemie, Linfomi e Mieloma (AIL), Bologna.

References

- 1. Palandri F, Piciocchi A, De Stefano V, Breccia M, Finazzi G, Iurlo A, et al. How the coronavirus pandemic has affected the clinical management of Philadelphia‐negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms in Italy‐a GIMEMA MPN WP survey. Leukemia. 2020;34:2805–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hultcrantz M, Wilkes SR, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM, Derolf ÅR, Eloranta S, et al. Risk and cause of death in patients diagnosed with myeloproliferative neoplasms in Sweden Between 1973 and 2005: a population‐based study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2288–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polverelli N, Breccia M, Benevolo G, Martino B, Tieghi A, Latagliata R, et al. Risk factors for infections in myelofibrosis: role of disease status and treatment. A multicenter study of 507 patients. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooper N, Ghanima W. Immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:945–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mesa R, Alvarez‐Larran A, Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Rambaldi A, Tefferi A, Vannucchi A, Verstovsek S, De Stefano V, Barbui T. COVID‐19 and myeloproliferative neoplasms: frequently asked questions. 2020. American Society of Hematology, COVID‐19 Resources, Version 3.0; May 4, 2020. https://www.hematology.org/covid‐2019/covid‐2019‐and‐myeloproliferative‐neoplasms [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pavord S, Thachil J, Hunt BJ, Murphy M, Lowe G, Laffan M, et al. Practical guidance for the management of adults with immune thrombocytopenia during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:1038–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Willan J, King AJ, Hayes S, Collins GP, Peniket A. Care of haematology patients in a COVID‐19 epidemic. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395:859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C. Video consultations for covid‐19. BMJ. 2020;368:m998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mesa R, Miller CB, Thyne M, Mangan J, Goldberger S, Fazal S, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a significant impact on patients' overall health and productivity: the MPN Landmark survey. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Questionnaire of satisfaction that was responded to by 87 patients who were included in the telemedicine project during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The questionnaire was administered to patients by telephone, by health professionals who were not directly involved in the haematological management.

Table S2. Correlation matrices. The two values reported in the cells are, respectively, the pairwise correlation coefficients between the attribution of high scores of the corresponding questions of each cluster and the significance level of each correlation coefficient. Q, question.