Abstract

This paper examines the governance of the COVID‐19 crisis in Spain. The main thesis is that the central reason for the pandemic's devastating outcomes was the relatively poor governance of the crisis as manifested by the country's lack of preparedness and its slow and delayed response. If we measure the three dimensions of governance (Mimicopoulos 2006), Spain came way short in efficiency: The lack of predictability in the institutional and policy environment hurt the response to the pandemic; in transparency: The lack of available and reliable data and the absence of information provided to the general public deeply undermined confidence and trust in the government as well adequate rand timely responses to the pandemic; and finally, in participation: The government rarely encouraged public input into decision making and failed to engage the opposition in a timely and constructive way.

Keywords: Spain, pandemic, governance, crisis, COVID‐19

1. INTRODUCTION

The first recorded case of COVID‐19 in Spain was a German tourist on vacation in the remote island of La Gomera in the Canary Islands at the end of January 2020. The patient was hospitalized and released after 2 weeks. At the time, the Spanish government took a complacent approach to the spread of COVID‐19, comfortable in the belief that the coronavirus was an external threat that was being imported by tourists from other countries, particularly Italy, rather than manifesting as a domestic public health problem. This all changed on February 26th when a citizen from Seville—who had not traveled abroad—tested positive. This was followed by the first recorded death of an individual with COVID‐19 in Valencia a week later on March 1st. This was the beginning of what would become a nightmare: According to data from the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), as of September 9th, 2020, the death toll from the virus in Spain had reached 29,594 (9th in the world in terms of deaths) and 534,513 confirmed cases (9th in the world in terms of numbers of confirmed cases).

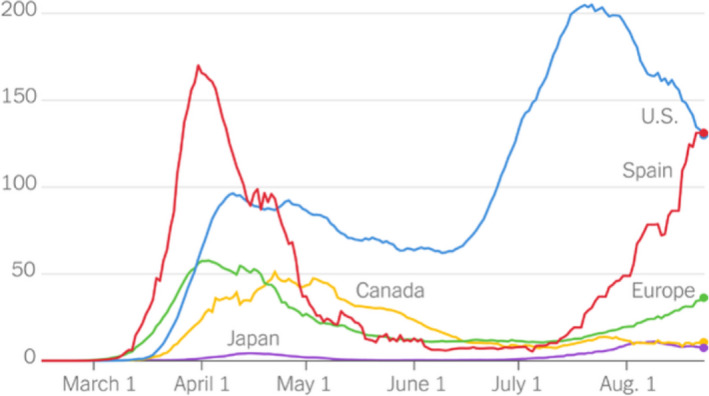

The lethality of the coronavirus and the high death toll are the first elements that stand out in the Spanish case. As of May 3rd, Spain already had the second highest death rate from the virus in Europe (10.1% of the people who were infected), behind only Italy, with 13.7%, and well ahead of the United States with 5.8%, as well as the third highest number of total deaths in Europe with 26,299 (behind Italy with 29,070 deaths and the United Kingdom with 28,809). The number of deaths peaked on May 24th with 28,752, and during the following weeks, there was a flattening of the curve and a deceleration in the number of cases and deaths. By early June, new confirmed infections fell to under 300 a day, from a peak in March of nearly 8,000 daily cases. By mid‐summer, however, there was a new surge of cases in many parts of the country as the virus bounced back with more than 5,000 cases a day detected on average. On the week of August 17th, the country's per capita rate of new cases has been five times larger than France's, six times larger than Portugal's, and 15 times larger than Japan's. Adjusted for population, Spain's outbreak even surpassed the US outbreak that week (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

New Cases Daily, per million residents. Moving averages of new daily cases for the most recent 7‐day period. By The New York Times | Sources: Johns Hopkins University and World Bank.

Several factors have been put forward to account for this grim outcome. First, Spain has a significant older population that is more vulnerable to the disease: 19.1% of the population are 65 years old or older, although it is worth noting that this figure is well below the likes of Portugal and Greece (both at 21.8%); Germany (21.4%); or France (20.3%), which all had significantly fewer deaths than Spain. Second, the country is well known for its particularly sociable way of life and socializing among people has been a major source of infections in the country.

Third, the country's healthcare system had been weakened by a decade‐long financial crisis. Indeed, the post‐2008 financial crisis had a profound effect on the country's public healthcare system because it forced the authorities to adopt deep spending cuts at a time when there was an increase in demand for healthcare services. The national health budget was cut in 2012 by 13.65%, making the Spanish healthcare budget one of the lowest in the European Union. The cuts particularly affected the elderly: In 2013, new cuts were implemented in the dependency programs for the country's elderly and disabled (€1,108 million), which are the parts of the population that are more vulnerable to COVID‐19 (Legido‐Quigley et al., 2013). The cuts from the crisis pushed a healthcare system that was already facing significant challenges due to demographic changes, as well as growing demands, poor resource management, and rising costs, to the brink (Morero et al., 2009; Pavolini & Guillén, 2013). Indeed, the COVID‐19 crisis has exposed the deficits of the Spanish health system, which is comparatively underfunded with only 6.4% of GDP, which is well behind other European countries and clearly lacks the capacity to handle major crises.

Furthermore, the governance of the pandemic in Spain, which is defined as the way that Spanish society managed policymaking and policy implementation during the COVID‐19 crisis, has left much to be desired. For the purpose of this paper, governance is understood as the process whereby a society makes important decisions, and determines who should be involved in decision making and how they will be held accountable (Graham et al., 2003). It looks at the Spanish state's ability to serve its citizens and other actors during the pandemic, as well as the manner in which public functions were managed. If “good” governance takes place when states efficiently allocate and manage resources to respond to collective problems (DESA, 2007), the management of this crisis does not meet those criteria. Indeed, if we measure the three dimensions of governance, namely: efficiency (predictability in the institutional and policy environment), transparency (availability and clarity of information provided to the general public), and participation (encouraging public input into decision making) (Mimicopoulos, 2006), the governance of the COVID‐19 crisis has been very deficient. This article seeks to explain why.

The main thesis of the paper is that a central reason for the pandemic's devastating outcomes in Spain was the relatively poor governance of the crisis as manifested by the country's lack of preparedness and its slow and delayed response. While Spain was not the only country that responded too late or was woefully unprepared to deal with the crisis, the lack of preparedness and the delayed response were not inevitable, as many other countries were far better prepared for the onset of the pandemic, responded earlier, and had much better outcomes. This article seeks to explain the causes that contributed to the lack of readiness and the delayed response in Spain. It focuses on the quality of governance and the political factors (e.g., a new coalition government, the polarization of Spanish politics, and the politization of the crisis) and constitutional and structural factors (e.g., the decentralized nature of the Spanish state) which hampered the government's response.

Indeed, contrary to other countries, the Spanish government was asleep at the wheel and turned a blind eye to the rising cases of the virus in the first weeks of the crisis. 1 While the private sector acted earlier (e.g., the Mobile World Congress which was scheduled to take place in Barcelona on February 13 was canceled, to which Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez responded on Twitter that the cancelation did not respond to reasons of public health in the country), the government insisted that there were no cases of local contagion and acted too late, even allowing mass gatherings to continue to take place as the number of deaths accelerated. The public statements of government officials that sought to downplay the risk of the pandemic until March 9th were a blunt testament of how woefully unprepared and unwilling the authorities were to deal with the crisis. On January 30th, Salvador Illa, Minister for Health, claimed that “we do not minimize anything…The System is prepared to confront this situation and we will follow it daily with transparent communications.” 2 .

Data from Our World in Data 3 and the Government Response Stringency Index 4 show that Germany and France acted more rapidly to impose restrictive measures which resulted in far fewer cases being recorded. The first reported death in Spain was on March 1st, and the Stringency Index that day was at 11.11. It took the government over a week until March 9 to ramp up the stringency measures (by March 9th the Stringency Index increased to 25), and it did not reach 80 until March 30th. In contrast, in France, where fewer deaths had occurred, it reached 87 by March 17th, in Germany with even fewer death it reached the highest level (76) on March 22. On March 22 with only 67 deaths, Germany's index was 76.85, and France's 87.96 with 562 deaths, while Spain was at 71.76, with far more recorded deaths (1,326).

The government has been widely criticized for not acting earlier and not stockpiling medical equipment when conditions deteriorated in Italy throughout February. On February 13th, Fernando Simón, the Director of the Center for Coordination of Health Alerts and Emergencies of the Ministry of Health, declared that “I am surprised by this excess of concern.” 2 On February 23rd, he further remarked that “in Spain there is no virus, the disease is not being transmitted, and there are no cases.” 2 By February 28th, the number of cases in Spain had reached 25, doubling in a single day. Yet, Simon still declared that “right now, this stage does not pose a situation of suspension of public acts,” 2 and also that “there is no [need for] measure of social distancing.” 2 On March 3rd, the Minister for Health Salvador Illa, recommended holding sporting events behind closed doors (after a Champions League soccer game between Valencia and Atalanta of Italy had taken place in Milan, where thousands of Valencia's fans travelled to Italy to support their team, many of whom returned to the country infected with COVID‐19). On March 4th, only 10 days before the government eventually declared the state of emergency, the National Security Council, the prime minister's highest advising institution on issues of national security, approved a report that ranked the risk that Spain would suffer a pandemic in 2020 as the most improbable of the 15 risks that were included in the National Security Strategy. A pandemic was ranked the sixth less dangerous risk, behind the risk of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

As late as March 8th, the government allowed massive demonstrations to mark International Women's Day to take place, which saw over 120,000 people gather in Madrid at an event that was blamed for propelling the spread of the virus in the city, and which saw three government ministers who had led the march testing positive. Meanwhile, Simon declared that “If my son asks me, [I would tell him] do what you want.” 2 On March 9th, Prime Minister Sanchez was confident enough to declare that [we have a] “shock plan that we are going to implement as soon as possible… We have a robust health system.” 2 That day the Madrid regional government closed schools and places of education. On March 13th, two days after the World Health Organization had declared the COVID‐19 crisis a global pandemic, and when Spain recorded 2,218 infections and 54 deaths, the government finally announced that they were looking into declaring a state of emergency. That same day also the number of infections reaches 4,209, with 128 deaths associated with the virus. Finally, the government declared the state of emergency and imposed a nationwide lockdown on March 14th. That day there were 7,793 cases and 292 deaths in the country. Two precious weeks when the coronavirus was stealthily spreading throughout the country were crucially lost. And despite the government claims, with Minister for Health Salvador Illa declaring on February 25th that “where masks are needed and where other medical devices are needed they will be available. In this case we do not have a shortage problem” 2 the country was severely lacking in personal protective equipment (PPE). By spring 2020, Spain had the highest number of health professionals infected anywhere in the world (out of Spain's 40,000 confirmed coronavirus cases, 5,400—nearly 14 percent —were medical professionals by the end of March 5 ), and there were persistent problems with the quality and reliability of the data the country could gather about the pandemic.

The state of emergency was initially established for 15 days. However, conditions continued to deteriorate, and by March 28th, the number of cases had hit 72,248, while deaths had risen to 5,690. The government was forced to increase the severity of the state of emergency on March 28th, banning all non‐essential activities for 2 weeks, which was vocally contested by many employers. The state of emergency was extended with parliamentary support multiple times and lasted through to June 20th. What explains this?

First, governance problems played a critical role in the crisis. As argued elsewhere and shown in international surveys from the likes of the World Economic Forum, the World Justice Project's Rule of Law, the World Bank's World Governance, and Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index, the institutional degradation that took place in the country in the years prior to the 2008 crisis led to the emergence of a Spanish version of crony capitalism, characterized by the misgovernment of the public, an outdated and inadequate policymaking process, an inefficient state, and an often corrupt and inefficient political class (Royo, 2014). All these data seemed to confirm a decline in institutional quality.

The government's response was further hampered by the decentralized nature of the Spanish political system. The 1978 Constitution established 17 autonomous regions with very significant powers, including as regards responsibility for the health systems and for the management of hospitals. As a result, Spain had become one of the most decentralized countries in the world in just over three decades. While the process has been largely marked by successes (Moreno, 2002), the literature has also shown how the country's decentralized system has been a key factor for income distribution and national/regional income inequality (İrepoğlu Carreras, 2016). The healthcare system was fully decentralized in 1991, and since then, it has been administered by 17 autonomous regional authorities, covering some 99.8% of the population. The national health authorities are responsible for coordinating health policy and for regulating pharmaceutical products, and all other health programs are managed by the regional authorities, with the exception of public health and sanitation functions, which are run by the municipalities. Over the years there have been concerns about the shortcomings and inefficiencies of the system, as well as calls for more coordination from central government to ensure the equality of care throughout the country and to minimize waste and overlap (Pavolini & Guillén, 2013). For instance, the central government assigned the responsibility for collecting statistics to the Autonomous Communities, which left the country without a central data source, making accurate performance comparisons between regions essentially impossible to undertake. The COVID‐19 crisis brought these shortcomings to the fore.

The tensions and inadequate coordination between the central government and the regional authorities became manifest very early on when the Madrid government decided to close schools and universities on March 9th, while the central government remained essentially idle. In the four precious days that passed until the central government issued the state of emergency and restricted the movement of people, many citizens left Madrid for their second homes, many likely bringing with them the virus and helping to spread it across the country. And one of the regional leaders, the president of Catalonia, a regional government that has been seeking independence from Spain and which was immersed in a simmering conflict with the central Spanish state, refused to sign a joint declaration with the central government to coordinate the country's lockdown measures.

Another factor that intensified the challenges of decentralization was the politization of the crisis, within the country which also hindered an effective and rapid response. This was manifested by constant differences and bickering between the central government and many of the regions (notably with the two most affected, Madrid and Catalonia, with the first ruled by a conservative PP/Ciudadanos coalition, and the second by a pro‐independence coalition), as well as by the lack of solidarity among regions. These differences were often played out in public, and they continued throughout the crisis, right until the end of the first phase of the crisis when the central government rejected the request from the Madrid regional government to be allowed to move to Phase I of the de‐escalation process scheduled for May 11th. Moreover, whereas in countries like France patients were evacuated from the most affected regions and taken to hospitals in other regions, in Spain there was, particularly at the beginning, only limited shift of medical equipment or movement of patients from one region to another, despite an early pledge for solidarity from the Minister for Health, Salvador Illa. Indeed, solidarity has been sorely missing as regions have largely acted independently to protect their own citizens, which stands in contrast with the outpouring of solidarity from Spanish citizens for the country's doctors and nurses. The crisis may have brought citizens together, but it has certainly further eroded the already fragile trust many citizens had for its government and politicians. Unsurprisingly, polls have shown that two‐thirds of the people believed that the government hid information about the pandemic from public view. 6

Furthermore, the crisis arrived on the heels of a period of political instability in Spain, when the country had held two general elections within a year that had resulted in a fragmented parliament, and a new coalition government formed in January 2020 between the Socialist Party and the far‐left Unidas Podemos (the first government coalition since the 1930s) that lacks a majority in Parliament, and survives with the support of a group of small parties with often divergent agendas. The literature has shown how divided party government is powerfully associated with fragmentation in policy implementation, and how legislative coalitions are more likely to cause political fragmentation in the face of greater uncertainty about sustaining a majority in parliament (Farhang & Yaver, 2016). In Spain, divisions between the two coalition parties regarding how to respond to the economic crisis caused by the pandemic emerged early on and played out in public view and had a clear impact on the government's policy responses.

When the government declared the state of emergency, the Basque and Catalan parties, part of the group of parties that has supported the election of Pedro Sánchez as Prime Minister, accused him of using the crisis to make a centralizing power grab. This was the paradox of an administration which had been elected on the promise of dialogue with Catalonia's pro‐independence government but that was since been forced by the pandemic to make an unprecedented intervention into the autonomous regions. This reliance on the nationalist parties made any parliamentary actions, including successive renewals of the estate of emergency, very difficult to establish throughout the crisis.

The fragile coalition government, particularly in the initial stages of the crisis, lacked the strength to take decisive action and seemed paralyzed from its internal divisions and competing agendas. Differences within the government itself also played out publicly. First, there were differences over the declaration of the state of emergency. While many members of the government from both PSOE and Podemos pushed for a swift declaration of a state of emergency when the number of confirmed cases in Madrid doubled on March 9, this move was opposed by one of the Government vice presidents, Nadia Calviño, on economic grounds, fearing the economic consequences of the decision, claiming that it would “spook the markets.” Sánchez remained on the fence until later that week, and was unwilling to commit to such drastic action as events overtook him. The lost days of inaction were decisive for the country as the number of cases continued growing and as Spain leapfrogged France and Germany to become the European country with the second highest number of cases.

Furthermore, these differences extended to the economic response to the crisis. After a 7‐hr cabinet meeting on Saturday March 14th, PSOE and Podemos were unable to reach an agreement on economic measures to respond to the crisis that would be designed to protect workers from loss of income. Many Socialists, led by Calviño, refused to accept the economic measures proposed by Podemos and instead prioritized controlling the budget deficit. In response, the leader of Podemos, Pablo Iglesias, Tweeted that “nobody should be left behind as happened in 2008” thus using a strategy of making public the differences within the executive as a means of exercising pressure on PSOE. In the end, the government was able to agree on a package of measures a few days later—but the tone of what was to come was set.

A virus exploits any weaknesses and the coronavirus undoubtedly benefitted from the delay in taking forceful and decisive decisions in the early stages of the crisis. Government actions were also marred by public mistakes that eroded public confidence, like the purchasing of 640,000 faulty testing kits from a Chinese company, or given the opacity of the country's mortality figures and testing data. In addition, the coronavirus crisis further intensified the polarization that has ravaged Spanish politics for the last few years, further complicating the government's ability to act. Party polarization can be a pathway to accountable government, but it can also become a problem when it includes disagreement about the democratic rules of the game. While there is little evidence that party polarization has promoted ideologically extreme policy outcomes (Lee, 2015), it has associated with “drift,” or preventing policy changes (Hacker & Pierson, 2010). In Spain, polarization made decisions to address the pandemic much harder.

Contrary to other countries, like neighboring Portugal, where the pandemic pushed political rivalries to one side, and as opposition parties supported the country's minority Socialist government's response to the pandemic, in Spain the crisis has only deepened these divides. The government slogan “Este virus los paramos unidos” [“United, we will stop this virus”] has done little to prevent the resurgence of the politics of confrontation in the country. Political polarization in Spain had intensified in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, which also resulted in the emergence of new political parties and in the further fragmentation of the party system as citizens run away from the traditional parties and sought answers and solutions in the extremes of the political spectrum. The formation of a social‐communist coalition government in January 2020 further deepened those fissures. The leader of the conservative opposition Partido Popular (PP), Pablo Casado, routinely referred to Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez as a “liar” throughout the crisis, and he regularly accused the government of incompetence and worse, including allegations the government had issued orders to hide the true mortality rates. Moreover, the far‐right Vox party, the third largest party in Congress, has repeatedly demanded Sánchez's resignation, while the pro‐independence Catalan government has been upbraiding the central government almost daily for its incompetence and paralysis. Citizens have also mobilized by banging pots and pans in protest at the government (and even once against the royal family following news of former King Juan Carlos questionable financial dealings). While the government has made repeated calls for national unity, it has largely taken unilateral decisions with little consultation with other political parties or social actors, which has only deepened the divide. On May 7th, the fracture reached its peak when the PP, which up to that point had supported three of the government's requests to extend the state of emergency in Congress, abstained in a vote and refused to support the government's request for a new extension (although the government was able to pass it with the support of other small parties).

The consequences of the crisis for the economy have been devastating, particularly for a country that was just emerging from the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis. Unemployment was already 14 percent before the COVID‐19 crisis started, and total debt was hovering around 100 percent of GDP, thus limiting the country's ability to borrow. According to the government's forecast, the Spanish economy will contract by 9.2% in 2020, and the unemployment rate will reach 19 percent in a V‐shaped crisis that will begin to subside by the end of 2020, with a positive forecast of 6.8% growth predicted for 2021. In response to the crisis, on March 17th, the government announced a plan to inject the equivalent of 20 percent of GDP into the economy to combat the looming economic crisis, authorizing more that €4bn in funds to fight the disease. Prospects are dire: Even with the end of the lockdown, the Spanish economy remains very vulnerable given the importance of the tourism sector (which represents 12 percent of GDP), which has essentially ground to a halt, as well as other traditional weaknesses in the economy, including the high proportion of temporary contract, as more than a quarter of all labor contracts are temporary. This facilitates employers’ shedding of jobs rather than resorting to alternative measures like reduced working hours and/or salaries as has happened elsewhere. Low productivity growth, and the structure of a business sector, being largely comprised of small and medium enterprises, further undermines the county's prospects of a rapid economic recovery. 7

Unsurprisingly, the Spanish government has been very active at the European level in seeking help, by urging EU leaders to take on the mutualization of debt and the issuing of coronabonds. In the end, in addition to the three safety nets of €540 billion already put in place by the EU to support workers, businesses, and governments, on July 21st, EU leaders agreed on an overall budget of €1.824 trillion for 2021–2027 to help the EU rebuild after the COVID‐19 pandemic that includes €390 billion in grants and €360 billion in loans (Camous & Claeys, 2020).

At the time of writing, in October 2020, the daily death toll and number of confirmed cases in Spain continues to grow, and the country is facing a second wave of infections. The central government has largely delegated the response to the crisis to the regional authorities and has offered support if they decide to impose their own states of emergency. Yet the response of the regional governments has been hindered by legal challenges against some restrictions that have been overturned by the courts.

2. CONCLUSIONS

This article has examined the governance of the COVID‐19 crisis in Spain and has analyzed the political and constitutional factors that hindered the country's response to the pandemic. If we measure the three dimensions of governance (Mimicopoulos, 2006), Spain fell far short in terms of: efficiency, as the lack of predictability in the institutional and policy environment hurt the response to the pandemic; regarding transparency, as the lack of available and reliable data and the absence of information provided to the general public deeply undermined confidence and trust in the government; and finally, regarding participation, the government rarely encouraged public input into decision making and failed to engage the opposition in a timely and constructive way.

The crisis exposed the weaknesses within Spain's new coalition government that operated in a very polarized political environment, but also failed to approach the crisis in an inclusive and transparent way. At the same time, the crisis also exposed major weaknesses in the Spanish decentralized system of public health governance, which divides powers among the central and autonomous regions’ governments. A virus that is highly transmissible, and crosses internal (and external) borders efficiently, would have required strong decisive national action from the outset (Haffajee & Mello, 2020). In Spain, however, the government's response was alarmingly slow and there was a significant lack of interjurisdictional coordination. This contributed to the fostering of confusion regarding the impact of the virus and the steps that were required to address it.

The imposition of the estate of emergency on March 14th was instrumental in addressing some of these issues, but by the time it happened the virus had already been spreading, and precious time had been lost. The difficulties that the government subsequently encountered in Congress when seeking to extend the estate of emergency (which led to horse‐trading and questionable concessions to small parties) further hampered its efforts, eroded trust, and undermined its response to the pandemic. In the end, in Spain (and many other countries like Italy and the United States) the opportunity to contain the pandemic through swift and unified national action was lost. The crisis has shown that a pandemic needs a nationally (and internationally) coordinated response. Countries like Germany (a federal country), South Korea, and Taiwan, which have prevented widespread community transmission, have been more successful because they were prepared before the pandemic hit them and they rapidly implemented a centralized national strategy based on widespread social distancing, mask wearing, testing, contact tracing, quarantines, limitations on social gatherings, and, when necessary, lockdowns. When Spain followed that strategy, in the spring of 2020, it was successful in sharply reducing the rates of new infections (Figure 1).

Indeed, the surge in cases in Spain in the summer of 2020, further, illustrates the difficulties of an ad hoc and decentralized approach to virus suppression. Since the lifting of the state of emergency in June, the responsibility to deal with COVID‐19 was largely transferred to the 17 regional governments. This has led to a mosaic of different rules (for instance, some authorities closed nightclubs again within weeks of reopening, imposed earlier closing times for bars, and banned smoking in public spaces, while others did not go that far), and wide disparities in the levels of testing and tracing. And many of these rules had to be changed when they failed to arrest the advance of the virus.

The summer surge also showcased the perils of premature reopening. Spanish officials, like those of many other countries, wanted to return to normalcy as soon as possible and made the mistake of thinking they could help the economy by prioritizing it over public health. They moved too quickly once the state of emergency was lifted to reopen bars and nightclubs, and to allow tourists back into the country without restrictions. Indeed, looking at the Government Response Stringency Index to illustrate the timing of the loosening of stringency measures, Spain loosened much more rapidly than many of its neighbors. For example, in mid‐June the Stringency Index was at 39.35, whereas France was still at 72 and Germany at 63. This resulted in the consequent rapid increase in cases that subsequently led to the introduction of more stringent measures (the country scored 62.5 by August 31st). By this time, it had become clear to the government that the best way to support the economy was to try to control the virus. 8

Moreover, in contrast with other European countries like Portugal, Germany, Italy, France, or the Netherlands where the pandemic brought together the main parties and reduced the level of political confrontation, in Spain, the polarization and lack of cooperation between the government and the main opposition party made the response to the crisis even harder to manage. The lack of dialogue (e.g., as the Spanish Prime Minister spent 2 weeks early in the crisis without reaching out to the leader of the opposition) is rooted in the polarization that has characterized Spanish politics for the last few years, and was another unfortunate feature of the response to the crisis.

Spain's lack of preparation also speaks to the country's governance problems. The deficits of the health system, as well as the lack of PPE and the persistent problems with the quality and reliability of the data about the epidemic, should lead to profound reforms of the country's healthcare system and in particular its health information and purchasing systems. This has been a systemic problem that requires urgent action in order to be prepared for any further surges of the pandemic and future health crises. The country urgently needs a strong alert and management system with emergency operational centers and also a public health agency with real executive powers. Finally, Spain has world renowned scientists and research centers but their transmission channels with global decision making processes and supply chains are not well developed. The country now demands technical audits at all levels to understand what has happened and to address the problems that these audits will uncover.

One of the main consequences of all this has been the further erosion of public trust in government. Indeed, the pandemic has already affected Spaniards’ views on politics, society, and Europe's place in the world. According to a June 2020 poll from the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR, 2020), 58 percent of Spanish voters have less confidence in the power of government than they previously did and they believe that their government performed poorly (only the French government with 61 percent fared worse among the nine countries polled). Furthermore, the poll also shows that only 21 percent of Spanish citizens trust experts and the authorities. Indeed, a “key finding of the [ECFR] poll [is] that many citizens view experts as bound up in the political process – subject to manipulation and instrumentalization – rather than as independent, standing apart from the political fray and providing objective truth.” Spaniards also believe that the EU responded poorly to the crisis: Only 16 percent of Spanish citizens strongly agree or agree that the EU lived up to its responsibilities during the pandemic. Yet, the overwhelming majority of Spaniards (80 percent) still want more EU cooperation.

All these speak to a growing loss in trust and confidence in politics in Spain. The crisis has also laid bare the weakening of the country's civic strength, and the social compact seems to be broken. For a political community to acquire and sustain legitimacy, over time requires a common purpose. The growing polarization and the conflict with and within Catalonia were already symptoms of the erosion of that common purpose. The pandemic seems to have accelerated it further. The COVID‐19 crisis has shown us, yet again, that in order to regain public trust and legitimacy, our governments must produce satisfactory outcomes, while providing appropriate voices to citizens in decision making.

We do not know when or how the pandemic will end, and it is still too early to predict how radically it will change our societies. In this regard, the pandemic may still have ramifications for Spanish politics and society that are not yet possible to anticipate. In the long term, Spain, with its large number of infected people, may benefit from a degree immunity within its population if new waves of the virus hit the country. It may well be that when the history of the pandemic is written, that Spain may not come across as a country with such a flawed response. For now, the pain is too deep and recent, and the consequences too devastating, to accept. More importantly, the crisis has exposed the absence of a national unifying purpose in Spain. At a time in which all hands should be on deck to fight the virus and to deal with its dramatic consequences, the crisis has intensified the search for scapegoats and has only worsened the country's political divide. That alone does not bode well for the future.

Royo S. Responding to COVID‐19: The Case of Spain. Eur Policy Anal. 2020;6:180–190. 10.1002/epa2.1099

NOTES

“As other nations struggled to contain virus, Spain turned a blind eye,” in The New York Times, Wednesday April 8, 2020.

From “No olvidar lo inolvidable” [Not forgetting the unforgettable], in Libertad Digital, May 5th, 2020.

The Government Response Stringency Index is a composite measure based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest). If policies vary at the subnational level, the index is shown as the response level of the strictest sub‐region.” See: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid‐stringency‐index?tab=chart&year=2020‐05‐07&time=2020‐01‐22..2020‐08‐31&country=~ESP

From “Virus Knocks Thousands of Health Workers Out of Action in Europe,” in The New York Times, March 24, 2020.

From “Spain's Coronavirus Crisis Accelerated as Warnings Went Unheeded,” in The New York Times, April 7th, 2020.

“Spain on course to be worst‐hit EU economy,” in Financial Times, April 13, 2020; and “Europe's drive to save jobs risks fueling north‐south inequality,” in Financial Times, April 13, 2020.

See “Virus Laggards,” in The New York Times, August 25th 2020, and “Spain Caught Off Guard by Resurgent Coronavirus,” in the Wall Street Journal, August 23rd, 2020.

REFERENCES

- Camous, A. , & Claeys, G. (2020). The evolution of European economic institutions during COVID‐19 crises. European Policy Analysis, 6(2), 328–347. 10.1002/epa2.1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreras İrepoğlu, Y. (2016). Fiscal decentralization and inequality: The case of Spain. Regional Studies Regional Science, 3(1), 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- DESA (Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat) (2007) Public governance indicators: A literature review. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- ECFR (European Council on Foreign Relations) (2020) Europe’s pandemic politics: How the virus has changed the public’s worldview. European Council on Foreign Relations; Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/europes_pandemic_politics_how_the_virus_has_changed_the_publics_worldview [Google Scholar]

- Farhang, S. , & Yaver, M. (2016). Divided Government and the fragmentation of American Law. American Journal of Political Science., 60(2), 401–417. 10.1111/ajps.12188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J. , Amos, B. , & Plumptre, T. (2003) Principles for good governance in the 21st century, Policy brief No. 15, Institute on Governance. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, J. , & Pierson, P. (2010). Winner Take‐All‐Politics. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee, R. L. , & Mello, M. M. Thinking globally, acting locally — The U.S. response to Covid‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(22), e75 10.1056/NEJMp2006740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, F. (2015). How party polarization affects governance. Annual Review of Political Sciences, 18, 261–282. 10.1146/annurev-polisci-072012-113747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legido‐Quigley, H. , Otero, L. , Parra, D. L. , Alvarez‐Dardet, C. , Martin‐Moreno, J. M. , & McKee, M. (2013). Will austerity cuts dismantle the Spanish healthcare system? BMJ, 346, f2363 10.1136/bmj.f2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐Moreno, J. M. , Alonso, P. , Claveria, A. , Gorgojo, L. , & Peiro, S. (2009) Spain: A Decentralized Health System in Constant Flux. BMJ, 338, b1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimicopoulos, M. G. (2006). Presentation to the United Nations world tourism organization knowledge management international seminar on global issues in local government: Tourism policy approaches, Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, L. (2002). Decentralization in Spain. Regional Studies, 36(4), 399–408. 10.1080/00343400220131160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavolini, E. , & Guillén, A. M. (2013). Healthcare systems in Europe under Austerity: Institutional reforms and performance. Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Royo, S . (2014) Institutional Degeneration and the Economic Crisis in Spain In Anna Z.‐K., & Coller X. (Eds.), Special issue of American Behavioral Scientist. The Economic Crisis from Within: Evidence from Southern Europe (Vol. 58, 1568–1591). [Google Scholar]