This commentary is an abridged version of a June 2020 submission from the Public Health Association of Australia to the Australian Parliamentary Senate Inquiry into Australia's response to COVID‐19. In many ways, Australia's response, especially in the early phase, has been exemplary – led by medical and scientific advice, and prioritising the health of the community as evidenced by our relatively low case numbers and fatality rates. Moving into the COVID‐19 recovery phase, it is essential to keep a broad perspective and recognise the contribution of public health, and the importance of resourcing public health expertise and capacity to learn from this pandemic and prepare for similar future emergencies.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) was notified about cases in Wuhan, in the People's Republic of China, of what would become known as COVID‐19, on 31 December 2019.1 The first case was recorded in Australia on 25 January 2020, less than a month later,2 and by 30 January 2020, the WHO had declared COVID‐19 to be a global public health emergency.1

Australia's cases in the first wave peaked at over 400 cases per day in late March 2020,2 and on 8 April 2020, the Australian Senate established the Select Committee on COVID‐19 to inquire into the Australian Government's response to the pandemic. PHAA's submission (number 448) to that Inquiry was the result of extensive consultation with PHAA's members and public health experts and was made in June 2020. The full submission and appendix are available from the PHAA website (https://www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/4622; https://www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/4623).

The Senate Inquiry will hear evidence from across the Australian community and make findings and policy and legislation recommendations.

Public health practice is about ‘Protecting Health, Saving Lives – Millions at a Time’.3 Public health is built on prevention activities, rather than health care and treating illness. Optimal health is about more than just not being unwell, it is also about the ways in which whole populations behave and interact and stay healthy. Public health responses during a pandemic are therefore critical to the maintenance of health in whole populations.

The initial response to the pandemic was on reducing the immediate health and economic impact, based on information available at the time. This included a portfolio of action across all 11 public health intervention types – public policy development, legislation and regulation, resource allocation, engineering and technical interventions, incentives, service development and delivery, education, communication, collaboration and partnership building, community and organisational development, and advocacy.

The Australian response and efforts of community members; health, community and service workers; and national advisory group and governments should be recognised and celebrated; they have demonstrated the extraordinary capacity of the community to deal with a significant health threat.

Compared with international rates, Australia has maintained low population and case‐fatality rates and has contributed only a very small number of cases and deaths to the international burden of disease. Whilst in part this may be due to being geographically remote (unlike European countries, for example), the efforts made by Australia's public health advisors and the ministers who operationalised their advice is to be acknowledged. Distancing has clearly worked so far – some of the best evidence being the huge reduction in influenza and other seasonal communicable diseases cases this year. However, we must be mindful that this is far from over. Globally, the virus is spreading faster now than early on in the pandemic, and there are many conditions under which Australia would encounter a second wave.

Prior to this pandemic, we are aware that major outbreak exercises had been conducted and response plans formulated and updated as a result. We know that this had made Australia as prepared for an outbreak as other countries (such as the UK and the USA), the major difference being that when the outbreak happened, the plans were activated. This is very much to Australia's credit. PHAA has recognised this through our special PHAA President's Award for Members of the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) on 12 May 2020.4

However, Australia's relative success has come at the expense of other public health activities as every available public health professional was pulled into the pandemic response. This reflects the capacity constraints brought about by years of inadequate investment in public health and disease prevention. Sustained increases in funding are needed to support building capacity and skilled public health workforces at federal and state and territory levels.

PHAA supports the efforts and response of the World Health Organization (WHO) within its limited remit and resources.5 We note that the WHO has produced a COVID‐19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan Monitoring and Evaluation Framework, which we hope was used in the Commonwealth COVID‐19 Senate Inquiry.6

Economic and social recovery from this world health crisis will depend on securing, protecting and improving population health. The broader public health impacts of the pandemic, and the responses to them, must be considered and given a higher priority than was initially possible or necessary. This submission provides an overview of some of these issues, highlighting examples of existing health issues and inequities being exacerbated and unforeseen consequences of the response, and forecasting longer‐term impacts.

Context

Public health responses during a pandemic are critical to the maintenance of health in large populations. There are a number of tools we have to assist us in this, which are briefly described here.

Assessing the response through the WFPHA lens

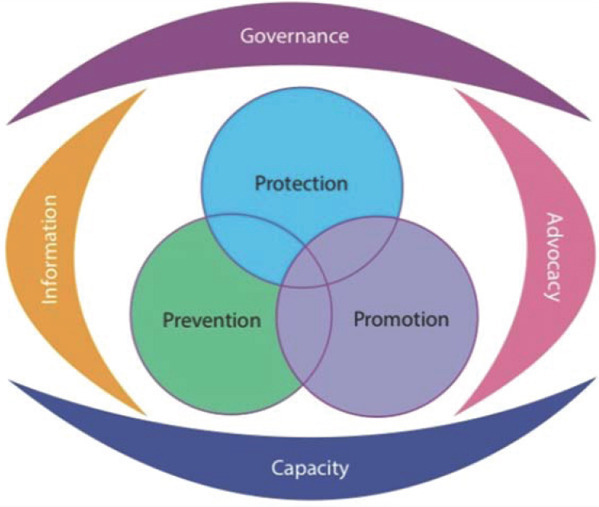

The World Federation of Public Health Associations (WFPHA) has developed a Charter, endorsed by the World Health Organization.7 A helpful lens through which to examine public health activities, all Charter elements were relevant to Australia's response to COVID‐19, although some elements were better activated than others. Core prevention–protection–promotion elements were activated quickly using pre‐existing mechanisms including standard public health surveillance notification and contact tracing, public education and more. Our laboratories and notification systems performed well.

Internationally, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Johns Hopkins University provided excellent and timely international information, and Australia utilised these sources at all stages. National and local information was updated in a timely way. Australian public health legislation was activated to good effect; nationally, public health unit capacity was upgraded; and advocacy for many constraining aspects of emergency management was disseminated effectively.

Figure 1.

The WHO‐endorsed WFPHA Charter for the Public's Health.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The United Nations Sustainable Development agenda is the internationally shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for our peoples and planet, now and into the future.8 The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an urgent call for action by all countries as part of the global partnership. They recognise the linkages between ending poverty, improving health and education, reducing inequality, protecting the environment, and encouraging economic growth.

Most SDGs, each of which has several target indicators, are relevant to the issue of COVID‐19 and the response, particularly those relating to:

-

•

No. 1: No poverty

-

•

No 2: Zero hunger

-

•

No 3: Good health and well‐being

-

•

No 4: Quality education

-

•

No 5: Gender equality

-

•

No 8: Decent work and economic growth

-

•

No 10: Reduced inequalities

-

•

No 15: Life on land

-

•

No 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions

From a broad and immediate public health response perspective, the response to the pandemic cannot be de‐linked from the SDGs. Food security, income protection, and secure housing are directly relevant as determinants of health: this pandemic has generated some major negative changes for many people in the areas of income and work, food security, gender and safety issues, and has highlighted and exacerbated many inequities. Contracting COVID‐19 has had negative health consequences for some Australians, and the effects of separation from other people has generated mental health consequences for many.

There are also a number of positive outcomes that have been reported as a result of the lockdown and distancing measures taken by countries. For example, there has been a measurable reduction in many health conditions such as other communicable and infectious diseases and reductions in road traffic accidents. Other countries have reported a reduction in cardiac events directly linked to a reduction in air pollution, which might be repeated in Australia.

Training and role of public health professionals

The health of the public cannot be protected without an adequately skilled and qualified workforce. This workforce was called on to underpin Australia's COVID‐19 response – not only frontline clinicians, nurses and other allied health, but also epidemiologists and other public health professionals.

Federal investment in public health education has been eroded over the last decade, with the loss of Public Health Education and Research Program (PHERP) funding. The Federal Government invested in a set of Foundation Competencies for Master of Public Health Graduates in Australia;9 however, not all Australian public health degrees are based on these, and the lack of an accreditation scheme for public health degrees reduces academic content oversight.

Only a minority of state and territory Departments of Health run ongoing dedicated public health training programs. Training opportunities for medical and non‐medical public health specialists are not consistently offered and run. More of such programs in all state and territories, as well as at Commonwealth level, are essential to ensure the adequacy of the future public health workforce.

The Government could increase public health knowledge requirements by requiring all frontline public health staff to have relevant public health qualifications and experience. More investment in specialist public health medicine training is required for medical doctors, along with access to practical as well as academic public health training such as that given to other health professionals. Public health department surge capacity for an outbreak such as COVID‐19 should be built on people with public health training, including training in contact tracing. The value of public health expertise as a speciality urgently needs enhancement.

The global and regional nature of public health is also directly relevant to public health education. Australia provides a significant amount of public health education and training for our region. The impact on international student numbers and the longer‐term impacts of the reduction in international students is yet be seen, but if enrolments decrease so will the capacity to offer full public health degree programs and to adequately supervise research students.

Interruption to our public health teaching programmes will have ramifications for regional biosecurity with a reduction in public health education and expertise. Australia benefits from strong public health training for those in less‐developed countries (especially our neighbours) in terms of social justice but also our own country's vulnerability, as well as revenues accrued from training international postgraduate public health students.

Government should:

-

•

increase the number of practical public health training programs

-

•

ensure all public health staff, both employed and in surge capacity, should be formally trained in public health, rather than just a health‐related discipline

-

•

support expansion of higher degree training in public health, including international students.

Social equity

The systemic, unfair and avoidable health and social impacts experienced from policy responses (in this case to COVID‐19) underline the moral basis for health equity. Equity is about pre‐empting harms to society from policy decisions before they eventuate, just as much as identifying particular vulnerable communities and providing assistance.

National and international COVID‐19 policy responses highlight the multiple connections within and between societies that have had a profound and ongoing impact on social wellbeing and vulnerability for groups at all levels of society.

With one in three people in Australia reporting that their household finances have worsened due to COVID‐19,10 the impacts are broad, but not universal. An extensive list of some potentially affected population groups includes workers in, and suppliers to: food and groceries, transport, waste management, overseas students, delivery drivers, emergency services, self‐employed people such as people working in the arts, all workers in healthcare institutions and those who provide care for the elderly.

People with pre‐existing inequities who are likely to be further significantly adversely affected are also numerous, including homeless people, chronically unwell people, elderly and infirm people, socially isolated, low income and less educated people, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, asylum seekers and others with no social protections.

Government should:

-

•

undertake better identification and coordination of services to vulnerable groups for all emergencies

-

•

ensure more equitable income support for all groups, including those self‐employed, and in recent casual employment

-

•

ensure ongoing coordinated investment in equitable public welfare supports and other structural determinants to protect and promote public welfare services.

One Health

COVID‐19 demonstrates that human and animal health are interdependent and closely linked to the health of the ecosystems, and that a One Health approach recognising these links is paramount to prevent future pandemics.

COVID‐19 is caused by SARS‐CoV‐2, a molecularly similar virus to a bat coronavirus. It is plausible that the virus has been transmitted from animals and subsequently adapted to human‐to‐human transmission due to environmental pressures. Several years ago, researchers in China discovered many coronaviruses in bats.11 Closure of ‘wet markets’ involving live animals as well as reductions in deforestation and urban and farmland incursions into natural areas are possible policy interventions.

SARS CoV‐2 is also similar to the SARS‐1 virus that caused the 2003 SARS epidemic, and to the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) virus first detected in 2012 that colonises camels and can be transmitted to humans.12

With three out of every four emerging and re‐emerging infectious diseases originating from animals, especially wildlife,13, 14 the Australian Government should:

-

•

incorporate a One Health approach to disease risk, surveillance and response (see the full submission for detailed recommendations).

Response

Coordination between Governments

The Australian Government's response to the pandemic has, overall, shown solid leadership, with decisive action taken in early establishment of the National Cabinet, encouraging cooperation and coordination between Commonwealth and State‐ and Territory‐level Governments. An Australian National Audit Office review of the Commonwealth Department of Health's Coordination of Communicable Disease Emergencies in 2017 noted that state and territory governments are primarily responsible for managing communicable disease emergencies, with the Commonwealth becoming involved when a national response is required, and in a primary role of coordination.15

Existing emergency response and disaster response plans in place meant that the necessity for a whole‐of‐government approach to a national public health crisis was clear.16 Taskforces, information hubs and policy statements across the spectrum of policy portfolios in government demonstrate the wide‐ranging nature of the response from governments.17

Government response was based on four elements designed to ‘flatten the curve’ and increase the capacity to respond, and was based upon National Cabinet commitment to honour and act on public health advice:

-

•

domestic and international border control

-

•

personal protective and other equipment and testing capabilities

-

•

contact tracing

-

•

‘social distancing’.

Whilst at times coordination between levels of government led to confusion because of conflicting advice, in a country as geographically large as Australia some differences were to be expected because of effectively dealing simultaneously with multiple outbreaks, responses for each of which are context‐specific.

The mechanism established to achieve coordination through the National Cabinet is sound, and PHAA supports a model which achieves cooperation and coordination on other significant national issues.

Communication issues

Communication in a time of crisis is always complex especially when the situation in rare, global and evolving quickly. There will be elements of uncertainty, and mistakes are inevitable, but lessons can be learned from this experience to be better prepared for the next event. From COVID‐19 so far, there are two areas relating to communication from which lessons may arise – planning and consistency.

The Australian Health Sector Response Plan includes provisions for communication, but it has not been implemented in its entirety. Putting these into practice in real‐time has highlighted areas for improvement. Mechanisms for key stakeholder consultation are limited, demonstrating the need for a stronger set of mechanisms for consultation to be established pre‐pandemic, and rehearsed and refined. Policies adopted in the crisis phase and thereafter lack evidence of consultation, such as via stakeholder reference groups.

The notable exception to this has been the consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, where the communication and engagement has been much stronger, with positive results.18

Public health and medical information dissemination to the public has come from multiple official sources, with a Federal response from the Prime Minister with medical information provided by the Deputy Chief Medical Officer on public health and epidemiology and by the Chief Medical Officer on medical and logistical issues, followed by various State and Territory level leaders and chief health officers. There is definitely a logic to this, as people ask both “What is Australia doing about this?” and “How does it affect me?” Managing differences in advice from these various sources is the challenge, to ensure it is not disjointed and confusing.

Improved internal Australian coordination of messages would have been helpful. It may have been better to have one national information source and set of rules, with allowances for different circumstances, especially in the early stages when everyone was trying to understand and adjust to the rapidly evolving situation. Clear explanations of variations in response and restrictions may have eased concerns and confusion, and increased confidence in the overall response.

Pre‐existing tested plans made the escalating outbreak response rapid and easy to follow for authorities. In terms of communication, in the future, it would be helpful for general information about planning exercises to be circulated as minor news items, so that the general public knows that emergency response is something that has been thought about and is ready to activate if needed, not a reflex reaction to evolving events.

The importance of crisis communication is highlighted here. Communication and behaviour change are central components of pandemic management.

Government should:

-

•

provide urgent funding for research in communication and behavioural insights into aspects of public health management, to inform and improve future communications.

-

•

ensure coordinated national communication strategy and information, with clear and logical explanations for differences where they exist.

Recovery

Australian CDC

The establishment of an Australian version of a centre for disease control (CDC) or its equivalent has been sought by public health experts for many years, but long resisted by Australian Governments. This would lead to a coordinated approach to both communicable disease control and environmental health problems, working together with the emerging evidence as emergencies unfold.

In 2018, the Australian Government released its response to the 2013 House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing report: Diseases have no Borders: Report on the Inquiry into Health Issues across International Borders. Following the COVID‐19 crisis, the Government may wish to review some of the responses to recommendations in that report. Recommendations regarding workforce development (13), and an audit of agency roles and responsibilities (14) were noted rather than supported. Significantly, a recommendation for an independent review to assess the case for establishing a CDC in Australia was not agreed, citing the development of the National Communicable Disease Framework to improve coordination and integrated response “without changing the responsibilities of government”.19

The COVID‐19 crisis has renewed calls for a designated public agency to provide scientific advice on communicable disease control. Australia is the only country in the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) without such an agency.20 The apparent success of Australia in minimising the number of cases and deaths from COVID‐19 may be interpreted by some as evidence that we have no need for a CDC, but many serendipitous factors worked in our favour in controlling COVID‐19, including our geography and the dominance of travel‐related cases as opposed to community transmissions. While the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) mechanism was pre‐existing and able to be activated quickly, our response would have benefitted from having a centralised agency to support and advise the AHPPC.

A CDC can provide:

-

•

a source of technical leadership and coordination

-

•

proficient communication of technical information and direction to the public and healthcare providers

-

•

training and mentoring to support workforce development

-

•

independent, expert‐led investigation of emerging health issues

-

•

ongoing analysis and interpretation of national data

-

•

engagement and co‐ordination with like agencies in the Asia Pacific region and internationally

-

•

scenario planning relating to future possible pandemics

-

•

development of new surveillance methods

-

•

routine review of international findings

-

•

evaluation of policy and program impact

-

•

assistance with the provision of surge capacity to the public health and other workforces.20

An independent agency to provide advice and education to the public about major emergencies and to coordinate relevant health advice would assist with protecting against inconsistent information and misinformation.

The Office of Health Protection was established in 2005 within the Federal Department of Health as an alternative but less well‐resourced approach, and it too has had to endure significant resourcing constraints and loss of specific expertise in public health.15 This can in turn impact upon the quality and adequacy of support to other key national advisory groups and networks such as CDNA or enHealth (the cross‐jurisdictional Environmental Health Committee that also reports to AHPPC). Nevertheless, calls for an Australian CDC continue.21, 22

PHAA recommends the Government establishes an independent Australian public agency to provide scientific advice and education, and coordination assistance on communicable disease control, including all diseases of public health importance.

Advisory bodies to Government

The PHAA commends the Government on the establishment of the National Cabinet for key decision making during the COVID pandemic. While not perfect, the cooperation and coordination between the Federal and State and Territory Governments have been key to Australia's successful response to date. The bipartisanship and decision making based on scientific evidence that National Cabinet involves is strongly commended. We hope to see a continuation of this on other issues into the future in Australia.

The PHAA is aware that two main bodies advise Government and the National Cabinet regarding the COVID‐19 response: one for health and the other for business.

The Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) “is the key decision‐making committee for health emergencies and is comprised of all state and territory Chief Health Officers and chaired by the Australian Chief Medical Officer.”23 Also on the AHPPC, is the chair of the Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA), which is the key advisory body regarding communicable disease control across jurisdictions in Australia. Members of the CDNA (State and Territory and Australian Government representatives, plus a representative from the Public Health Laboratory Network of Australia) have significant expertise in diagnosis, notification systems, monitoring, epidemiology and evidence‐informed implementation of public health responses.

This network has operated efficiently under immense pressure due to the many roles members also carry within their jurisdictions. In recent years, resourcing of basic public health infrastructure has not been maintained across most jurisdictions, leaving important shortfalls in the capacity to undertake basic public health functions, particularly when surge capacity is needed.

The Government established on 25 March 2020 the National COVID‐19 Coordination Commission. However, there are serious questions about this Commission which was appointed without any consultation and is right now considering project proposals.

-

•

Who are and what was the selection process for the membership?

-

•

What are the declarations of conflicts of interest and how are those conflicts being addressed?

-

•

What are the processes by which a proposal is put before the Commission?

-

•

What are the guidelines they are operating under to make recommendations on particular project proposals?

-

•

What accountability and transparency measures are in place for the important tasks of this Commission?

-

•

What will be the impacts on our recovery from COVID‐19 of this opaque and unilateral decision?

According to the Commission's website, it aims to “coordinate advice to the Australian Government on actions to anticipate and mitigate the economic and social impacts of the global COVID‐19 pandemic…The Commission is advising the Prime Minister on all non‐health aspects of the pandemic response”. PHAA has concerns that this Commission, as currently established, will not be able to achieve this aim, and is not focused across all aspects implied in the ambitious aim to begin with.

A quote from the Chair, Mr Neville Power, listed on the website says the Commission is to “help minimise and mitigate the impact of COVID‐19 on jobs and businesses, and to facilitate the fastest possible recovery of lives and livelihoods once the virus has passed”.24 This provides a clear and concise focus on the economic impacts but does not adequately reflect or reference the social impacts, which will be substantial.

Another indication that the focus is clearly on economic rather than the social impacts is the membership of the Commission. The members include former CEOs and senior executives of Fortescue Metals, Smorgens Steel Group, Telstra, IBM, Toll Holdings, EnergyAustralia, Shell, BHP Billiton, Dow Chemical Company, DowDuPont, and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. While this creates a particular economic focus, there do not appear to be any members whose experience and expertise suggest a community and social focus.

The Commission membership does not appear to constitute expertise to allow it to fulfil its designated purpose. The members lack apparent experience and expertise in a broad range of non‐economic issues upon which the Government will need advice. The issues raised in this submission are an example of these types of issues, for which a clear channel of advice of Government is severely lacking. The current Commission is an inappropriate vehicle for that advice.

PHAA strongly recommends that:

-

•

the stated purpose and terms of reference of the existing Commission are amended to reduce the focus to economic issues, and to provide clear and transparent processes and guidelines.

-

•

a reduced emphasis on fossil fuels and a greater emphasis on economic stimulus that reflects the urgent need for action in relation to the climate crisis. This will require additional members with that expertise and interest.

-

•

another Commission be established to provide advice on non‐economic issues. This new Commission should be comprised of members with a diverse range of backgrounds in social policy and programs, to provide advice on impacts on particular sectors of society, and how to ‘build back better’.

Conclusion

The response from Australia to the COVID‐19 pandemic has in many ways been exemplary – unashamedly led by medical and scientific advice, bipartisan, cooperative and decisive. And we have relatively low incidence and fatality rates to show for it.

However, there are always lessons to be learned from the details, particularly in relation to communication, and the impacts of both the pandemic and the response on particular population groups. There has been evidence of significant increases in health‐related investment due to COVID‐19. However, there is no clear evidence or even active discussion of an increase in the resourcing of public health expertise and capacity. Given this has been a public health crisis, which is yet to fully play out, and which many experts suggest will not be the last, this is not a sustainable situation.

Several months since the pandemic was declared, we must retain the sensible decision‐making and think more holistically and long term than a simple snap back to business as usual. This involves:

-

•

sustained increased funding for public health at federal and state and territory levels

-

•

supported training and capacity building for the public health workforce

-

•

establishment of an Australian independent designated public agency to provide scientific advice and education, and coordination assistance on communicable disease control, including all diseases of public health importance

-

•

the real living wage provided through social welfare supplementary payments being retained to allow recipients to focus on attaining new jobs as the recovery progresses, instead of being plunged into poverty requiring a full‐time focus on basic survival needs

-

•

services provided in recognition of the likely longer‐term impacts of the pandemic

-

•

a healthy recovery that recognises the links between human, economic and planetary health

-

•

strong action on climate change, led by scientific advice, which is required to address underlying vulnerabilities to pandemics including deforestation (making pandemics more likely to occur), and air pollution (making people more vulnerable to the effects of coronavirus).

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; Genva (CHE): 2020. Timeline of WHO's Response to COVID‐19 [Internet]https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/29‐06‐2020‐covidtimeline [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duckett S, Stobart A. Grattan Institute; Melbourne (AUST): 2020. Australia's COVID‐19 Response: The Story So Far [Internet]https://grattan.edu.au/news/australias‐covid‐19‐response‐the‐story‐so‐far/ [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomberg School of Public Health . Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore (MD): 2020. What is Public Health? [Internet]https://www.jhsph.edu/about/what‐is‐public‐health/ [cited 2020 Jun 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health Association of Australia . PHAA; Canberra (AUST): 2020. PHAA President's Award to be Given to the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee [Press Release] May 12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . 5th ed. WHO; Geneva (CHE): 2005. Constitution of the World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva (CHE): 2020. COVID‐19 Strategic Preparedness and Response (SPRP) Monitoring and Evaluation Framework. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomazzi M. A global charter for the public's health—the public health system: Role, functions, competencies and education requirements. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(2):210–212. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations . UN; New York (NY): 2020. Sustainable Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somerset S, Robinson P, Kelsall H, editors. Foundation Competencies for Public Health Graduates in Australia. 2nd ed. Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australia; Canberra (AUST): 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Bureau of Statistics . ABS; Canberra (AUST): 2020. 4940.0. ‐ Household Impacts of COVID‐19 Survey, 14–17 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams S. Where Coronaviruses Come From. TheScientist. 2020;24(67011) [Internet]. January. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan Y, Zhao K, Shi ZL, Zhou P. Bat Coronaviruses in China. Viruses. 2019;11(3):210. doi: 10.3390/v11030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolhouse MEJ, Gowtage‐Sequeria S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(12):1842–1847. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian National Audit Office . ANAO Report No.: 57 2016–17 Performance Audit. Government of Australia; Canberra (AUST): 2017. Department of Health's Coordination of Communicable Disease Emergencies. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elphick K. Research Paper Series 2019–20. Australian Department of Parliamentary Services; Canberra (AUST): 2020. Australian COVID‐19 Response Management Arrangements: A Quick Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parliamentary Library Research Branch . Research Paper Series 2019–20. Australian Department of Parliamentary Services; Canberra (AUST): 2020. COVID‐19 Australian Governent Roles and Responsibilities: An Overview. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crooks K, Casey D, Ward JS. First Nations peoples leading the way in COVID‐19 pandemic planning, response and management. Med J Aust. 2020 doi: 10.5694/mja2.50704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Australian Department of Health . Government of Australia; Canberra (AUST): 2018. Australian Government Response to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing Report: Diseases have No Borders: Report on the Inquiry into Health Issues Across International Borders. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCall BJ, Young MK, Cameron S, Givney R, Hall R, Kaldor J, et al. The time has come for an Australian Centre for Disease Control. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(3):300–303. doi: 10.1071/AH13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Medical Association . AMA; Canberra (AUST): 2017. Australian National Centre for Disease Control (CDC): AMA Position Statement. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes P, Bergin A. In: After COVID‐19: Australia and the World Rebuild. Coyne J, Jennings P, editors. Vol 1. Australian Strategic Policy Institute; Canberra (AUST): 2020. Risk, Resilience and Crisis Preparedness; pp. 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Department of Health . Government of Australia; Canberra (AUST): 2020. Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) [Internet]https://www.health.gov.au/committees‐and‐groups/australian‐health‐protection‐principal‐committee‐ahppc [cited 2020 Jun 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet . Government of Australia; Canberra (AUST): 2020. National COVID‐19 Coordination Commission [Internet]https://www.pmc.gov.au/nccc [cited 2020 Jun 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]