Dear Editor,

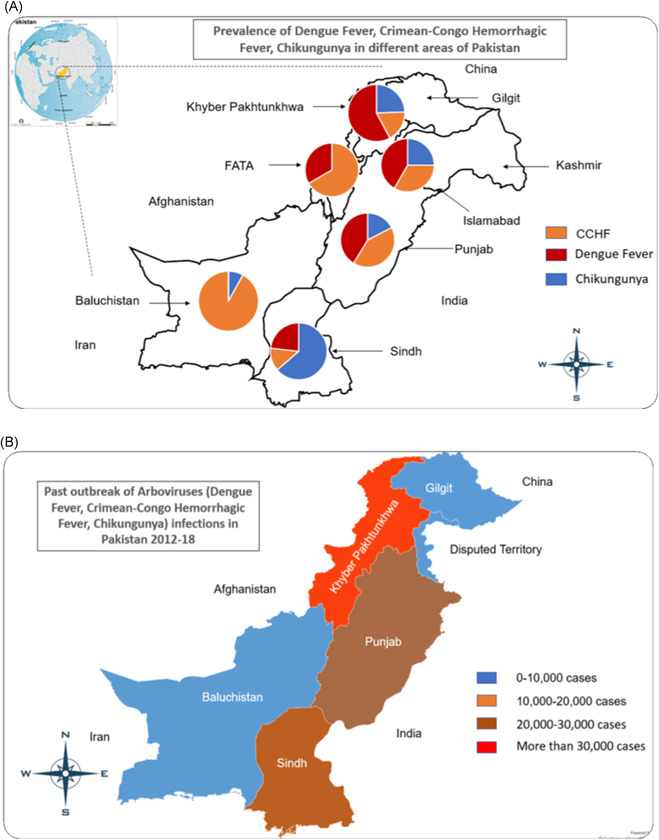

The impact of the co‐epidemics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and other infectious diseases 1 , 2 , 3 on an already delipidated healthcare system in Pakistan has been highlighted recently in a few studies 4 , 5 ; this enormous decimation continues to rise. The current pandemic of COVID‐19 caused by novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), as of October 30, 2020, has reached 219 countries, taken more than 1 million lives, and has 44.5 million confirmed cases around the globe. 6 , 7 In Pakistan, the number of COVID‐19 cases is escalating rapidly (328,602 cases), with the death toll crossing 6000 so far. 7 Simultaneously with the devastating effect of COVID‐19 on health facilities, co‐concurrence of other viral infections, including dengue, chikungunya, and Zika, might become a significant public health issue in Pakistan in the coming days. However, it has been confirmed that Pakistan is endemic to arboviral infection, as shown in Figure 1A,B, 8 Catastrophic effects were reported in Latin America 9 , 10 and Asia, 5 , 11 , 12 where SARS CoV‐2 outbreaks occurred during the dengue seasonal transmission period. The latest study from Brazil indicates that dengue, chikungunya, and Zika have undergone a major upsurge during the COVID‐19 pandemic season. 13

Figure 1.

(a) Prevalence of Arbovirus Infections in different localities of Pakistan. (b) Overall prevalence of Arbovirus Infections including Dengue Fever, Crimean‐Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) and Chikungunya from past few year in Pakistan (Data is retrieved from National Insitutue of Health, Pakitstan (From 2012 to 2018)).

In the early stage of the disease, arbovirus infection (dengue, chikungunya, Zika) and COVID‐19 exhibit similar clinical and laboratorial manifestations, thereby rendering the diagnoses more difficult. 14 Dreadfully, in serological testing, false‐positive results have been identified as dengue fever, later verified as COVID‐19. 14 , 15 , 16 Consequently, the misdiagnosis has impaired appropriate management and treatment of patients, thus increasing the prevalence of the disease with adverse clinical outcomes. 17

Pakistan is the world's fifth most populated country with a population of over 216 million; surprisingly, since 1995, its population has grown by 176 million. 18 As a result of an abrupt growth rate of 2.04%, 19 the demand for resources has also risen. This led to rapid unplanned urbanization along with potential health risks, stagnant water, drainage blocks, and waste dumps. These are the most favorable conditions for the propagation of multiple arboviral infections. 20

Pakistan's healthcare sector is currently faced with chronic low‐funding problems, massive workforce shortage, ineffective operational coordination, and medical equipment constraints. Appallingly, Pakistan has never planned to deal with major public health crises, which have doubled in response to COVID‐19 outbreaks. Quarantine and lockdowns, an essential prevention measure for the pandemic, may have contributed to an upsurge in outbreaks of arboviruses. During this lockdown, the population lives close together for a long time, which facilitate breeding for arthropods/mosquitoes in and around houses. 17 The high prevalence of arboviruses in developing and low‐income countries such as Pakistan, which have insufficient access to sanitation, closed water supply, and hygiene, raises the risk of vector reproduction and, therefore, increased arboviral infections, which is of grave concern while concomitant with COVID‐19. 21

In view of this trend of arboviral infections worldwide, Pakistan's healthcare sector is now at high risk for potential outbreaks. Provincial public health authorities must also not overlook other emergent arboviral pathogens already present in Pakistan before the arrival of co‐epidemics. The authorities must actively enforce vector control programs and segregation of patients to avoid further upswings of vector‐borne disease. Failure to continue screening programs for concurrent diseases and sensible allocation of new funding and facilities to COVID‐19 could have severe ramifications for Pakistan due to the healthcare system's downturn.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ding Q, Lu P, Fan Y, Xia Y, Liu M. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1549‐1555. 10.1002/jmv.25781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gayam V, Konala VM, Naramala S, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes of patients coinfected with COVID‐19 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the USA. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2181‐2187. 10.1002/jmv.26026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ribeiro VST, Telles JP, Tuon FF. Arboviral diseases and COVID‐19 in Brazil: Concerns regarding climatic, sanitation and endemic scenario. J Med Virol. 2020;92(11):2390‐2391. 10.1002/jmv.26079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haqqi A, Khurram M, Din MSU, et al. COVID‐19 and Salmonella Typhi co‐epidemics in Pakistan: a real problem. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.26293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haqqi A, Awan UA, Ali M, Saqib MAN, Ahmed H, Afzal MS. COVID‐19 and dengue virus co‐epidemics in Pakistan: a dangerous combination for overburdened healthcare system. J Med Virol. 2020:jmv.26144. 10.1002/jmv.26144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. COVID‐19 Coronavirus Pandemic . 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 7. COVID‐19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-27-october-2020. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- 8. Badar N, Salman M, Ansari J, Ikram A, Qazi J, Alam MM. Epidemiological trend of chikungunya outbreak in Pakistan: 2016–2018. PLOS Neglect Trop Dis. 2019;13(4):e0007118. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Magalhaes T, Chalegre KDM, Braga C, Foy BD. The Endless Challenges of Arboviral Diseases in Brazil. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. Vol 5; 2020:75. 10.3390/tropicalmed5020075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Silva NM, Santos NC, Martins IC. Dengue and Zika viruses: epidemiological history, potential therapies, and promising vaccines. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020;5(4):150. 10.3390/tropicalmed5040150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lam LT, Chua YX, Tan DH. Roles and challenges of primary care physicians facing a dual outbreak of COVID‐19 and dengue in Singapore. Fam Pract. 2020;37(4):578‐579. 10.1093/fampra/cmaa047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rahman MT, Sobur MA, Islam MS, Toniolo A, Nazir KNH. Is the COVID‐19 pandemic masking dengue epidemic in Bangladesh? Journal of Advanced Veterinary and Animal Research. 2020;7(2):218‐219. 10.5455/javar.2020.g412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. do Rosário MS, Siqueira IC. Concerns about COVID‐19 and arboviral (chikungunya, dengue, Zika) concurrent outbreaks. Braz J Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1016/j.bjid.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yan G, Lee CK, Lam LTM, et al. Covert COVID‐19 and false‐positive dengue serology in Singapore. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):536. 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30158-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Waterman SH, Paz‐Bailey G, San Martin JL, Gutierrez G, Castellanos LG, Mendez‐Rico JA. Diagnostic laboratory testing and clinical preparedness for dengue outbreaks during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1339‐1340. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lustig Y, Keler S, Kolodny R, et al. Potential antigenic cross‐reactivity between SARS‐CoV‐2 and dengue viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilder‐Smith A, Tissera H, Ooi EE, Coloma J, Scott TW, Gubler DJ. Preventing dengue epidemics during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(2):570‐571. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fatima Z. Dengue infection in Pakistan: not an isolated problem. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):1287‐1288. 10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30621-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Franklinos LH, Jones KE, Redding DW, Abubakar I. The effect of global change on mosquito‐borne disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(9):e302‐e312. 10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30161-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fatima Z, Afzal S, Idrees M, et al. Change in demographic pattern of dengue virus infection: evidence from 2011 dengue outbreak in Punjab, Pakistan. Public Health. 2013;127(9):875‐877. 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eder M, Cortes F, Teixeira de Siqueira Filha N, et al. Scoping review on vector‐borne diseases in urban areas: transmission dynamics, vectorial capacity and co‐infection. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):90. 10.1186/s40249-018-0475-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.