Graphical Abstract

Discussion on the observed association between unique populations of circulating monocytes and severity of COVID-19.

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its attendant pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has precipitated an enormous research effort into characterizing immune system responses to the virus. Given the public health and economic burdens of the pandemic, a great deal of this research has focused on efforts to produce immunogenic vaccines and develop effective antiviral treatments against SARS-CoV-2. Early in the pandemic, however, it was observed that a pronounced inflammatory cytokine storm associated with severe COVID-19,1 and as such, some effort has been made to characterize the etiology of this phenomenon.

Given their known prominent role in mediating early inflammatory responses in the innate immune system, monocytes and macrophages naturally have received considerable attention. In the early months of the pandemic, a variety of observational studies were published that noted alterations in circulating monocyte populations and functions during COVID-19 of varying severity. These changes have been somewhat inconsistent in the literature, but the general pattern includes increases in the population of pro-inflammatory and disease-associated phenotypes such as intermediate and nonclassical monocytes, as well as downregulation of monocyte HLA-DR expression and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6. For a fuller discussion of these early observations than is possible here, I point readers to my previous review on this topic,2 which surveyed the monocyte and macrophage literature relevant to COVID-19 through approximately mid-June of 2020. This editorial will primarily focus on more recent findings, including some limited empirical studies, relevant to monocyte biology and COVID-19 within the context of the featured article.

In this issue of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology, Zhang et al.3 report an observation of an unusual circulating population of monocytes with pronounced vacuolation under microscopy, and increased forward scatter by flow cytometry, in patients with COVID-19. These monocytes displayed elevated expression of the nonclassical monocyte marker CD16, as well as increased expression of M1 and M2 macrophage markers including CD80 and CD206, respectively. Additionally, monocytes from COVID-19 patients had increased intracellular staining for pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α and IL-6 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, providing further evidence for a heterogeneous monocyte response that encompasses aspects of both type 1 and type 2 innate immune responses.

In my opinion, it is likely that the most important observation from this study is the altered distribution of monocyte subpopulations during COVID-19. Human monocytes are most often grouped based on relative expression of CD14 and CD16 into classical (CD14+CD16―), intermediate (CD14+CD16+), and nonclassical (CD14lowCD16+) phenotypes.4 Monocytes expressing higher levels of CD16 (i.e., from the intermediate and nonclassical phenotypes) are often associated with increased disease severity. However, while this is a routine biomarker or predictor of disease severity in immunology research, whether these cells contribute directly to disease or are simply a by-product (and therefore convenient marker) of severe disease is not well understood.

Indeed, this is a question still unanswered by observational COVID-19 studies like Zhang et al. and other studies on monocyte distributions during this disease. The extent of the phenotypic changes reported by Zhang et al. is not known to occur in individuals with chronic diseases or pro-inflammatory conditions, and so SARS-CoV-2 infection likely does impact circulating monocyte populations. Nevertheless, preexisting differences in monocyte subpopulation distributions may also play a role in determining the severity of disease in COVID-19 patients. Advanced age and obesity are perhaps the two largest risk factors for severe COVID-19, and CD16+ monocyte subpopulations are well known to be increased by aging4 and obesity.5 While it is not yet entirely clear whether basal inflammation contributes to severity of COVID-19, the association between COVID-19 severity and CD16+ monocytes—as well as the link between these cells and risk factors such as age and obesity—suggest that altered monocyte subpopulations may be a causative factor in COVID-19 disease severity independent of the infection’s direct impact on circulating proportions of these cells. While there have been some high-profile attempts to characterize immune system kinetics during COVID-19 which have shown disease-related expansion of CD16+ monocytes,6 the lack of baseline pre-infection data in these studies makes this question currently unanswerable.

Moreover, while CD16+ monocyte increases during COVID-19 are supported by early observations by other groups (reviewed in Ref. 2), recent high-profile studies have also found decreases in these cell populations with increasing COVID-19 severity.7 The regulation of monocyte phenotype by SARS-CoV-2 is therefore probably multifactorial, and the contribution of the various subpopulations to COVID-19 may be dependent on immune or other responses that are not yet understood.

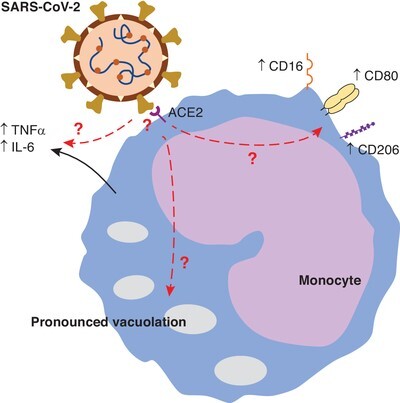

Zhang et al. additionally provide confirmatory (but nevertheless important) information that is essential for postulating a role for monocytes in COVID-19-associated cytokine storm. Namely, they have provided data demonstrating viremia in COVID-19 patients, as well as the expression of the virus receptor (ACE2) on monocytes. While others have described these as well, this remains important in that (a) the virus must be in the blood in order to encounter circulating monocytes, and (b) those monocytes must express a receptor for the virus in order to mount an inflammatory response. Increases in monocyte-derived macrophages in the lungs during COVID-19 has been described,8 so monocytes certainly have an important role to play as precursors to lung-infiltrating macrophages, but the role of undifferentiated monocytes in contributing to cytokine storm during COVID-19 remains controversial. However, the observations that monocytes express the cellular receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and that SARS-CoV-2 is detectable in the blood are key preliminary indicators that these cells may be important contributors to systemic pathology of COVID-19. Indeed, in vitro studies have confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 infection induces cytokine release and metabolic activation in isolated human monocytes,9 lending more credence to a role for monocytes in mediating cytokine storm. Nevertheless, while these are important observations, it remains to be determined whether the findings in this paper reflect direct stimulation of monocytes by SARS-CoV-2, or whether these changes are indirect resulting from a change in the monocyte milieu. A summary of Zhang et al.’s findings and important remaining questions is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Severe COVID-19 is associated with the presence of atypical monocytes. In a sample of COVID-19 patients, a population of monocytes is observed with high forward scatter by flow cytometry. A more extensive profiling of these cells demonstrated that they are highly vacuolated and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6. Additionally, they express the intermediate/nonclassical phenotype marker CD16 as well as mature macrophage markers CD80 and CD206. Finally, circulating monocytes are shown to express ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 receptor. Questions (marked with a red “?”) remain as to whether direct binding of SARS-CoV-2 to monocytes mediates these changes, or whether the mechanism of actions result from indirect stimulation

In summary, Zhang et al. have provided important data reflective of potential contributions of monocytes to viral cytokine storm during COVID-19, as well as observations reflecting a possible role of shifts in monocyte subpopulations in mediating severity of the disease. While important questions remain, and empirical evidence for these roles for monocytes is currently lacking, this paper adds to a growing body of literature reflecting the role of dysregulation in the myeloid cell compartment as a basis for COVID-19 severity.

Footnotes

See corresponding article on R 470R

References

- Huang C, Wang Y, Xingwang L, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BD. Severe COVID-19 and aging: are monocytes the key? Geroscience. 2020;42:1051-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Guo R, Lei L, et al. COVID-19 infection induces readily detectable morphological and inflammation-related phenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;109:13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BD, Yarbro JR. Aging impairs mitochondrial respiratory capacity in classical monocytes. Exp Gerontol. 2018;108:112-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poitou C, Dalmas E, Renovato M, et al. Cremer, I. CD14dimCD16+ and CD14+CD16+ monocytes in obesity and during weight loss: relationships with fat mass and subclinical atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2322-2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann ER, Menon M, Knight SB, et al. Longitudinal immune profiling reveals key myeloid signatures associated with COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Schrepping J, Reusch N, Paclik D, et al. Deutsche COVID-19 OMICS Initiative (DeCOI). Severe COVID-19 is marked by a dysregulated myeloid cell compartment. Cell. 2020;182:1419-1440.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, et al. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:842-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codo AC, Davanzo GG, Monteiro LB, et al. Elevated glucose levels favor SARS-CoV-2 infection and monocyte response through a HIF-1α/glycolysis-dependent axis. Cell Metab. 2020;32:437-446.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]