PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/dom.14269.

The world is currently grappling with a dual pandemic of diabetes and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Several articles published in the recent issues of Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism and elsewhere have raised concerns about a bi‐directional relationship between these two health conditions. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 It is now undoubtedly proven that diabetes is associated with a poor prognosis of COVID‐19. 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 On the other hand, COVID‐19 patients with diabetes frequently experience uncontrolled hyperglycaemia and episodes of acute hyperglycaemic crisis, requiring exceptionally high doses of insulin. 1 , 2 , 5 , 7 , 9 , 14 More intriguingly, recent reports show that newly diagnosed diabetes is commonly observed in COVID‐19 patients. 2 , 3 , 5 , 15 However, this has not been systematically studied before. Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis to examine the proportion of newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID‐19 patients.

This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) 16 and Meta‐analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) 17 guidelines (see Figure S1 and Table S1 for checklists), and is registered with PROSPERO (registration no. CRD42020200432). Two authors (TS and YC) independently searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase and Scopus databases and preprint servers (medRxiv and Research Square) until 2 November 2020. We considered observational studies providing data on the number or proportion of COVID‐19 patients (laboratory confirmed or clinically diagnosed) with newly diagnosed diabetes. We excluded observational studies that were conducted only among patients with diabetes, case reports, case series, letters, editorials, commentaries and review articles. Newly diagnosed diabetes was defined as new‐onset diabetes (no prior history of diabetes with fasting plasma glucose [FPG] ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or random blood glucose [RBG] ≥ 11.1 mmol/L and HbA1c < 6.5%) or previously undiagnosed diabetes (FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or RBG ≥ 11.1 mmol/L and HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% only). 18 We used the search terms ‘new‐onset diabetes’, ‘newly diagnosed diabetes’, ‘incident diabetes’, ‘transient hyperglycaemia’ and ‘secondary hyperglycaemia’ in conjunction with ‘COVID‐19’ (see the supporting information for search strategies). No language restrictions were applied. We also checked the reference list of relevant articles to identify additional eligible studies. If the study cohorts overlapped (i.e. patients from the same hospital with similar time periods of data collection), then the study with the largest sample size was selected. Data on first author name, country, study design, hospital name, study period, age, sex, total number of patients, number of patients with newly diagnosed diabetes, definition of newly diagnosed diabetes, time of diagnosis and type of diabetes were extracted independently by the same two authors (TS and YC) using a data extraction form that was adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration. 19 We did not contact the authors of the included studies to obtain missing data because of time constraints. The National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for observational studies was used to assess the quality of the included studies. 20 Disagreements in study selection, data extraction and quality assessment were resolved by consensus between the two authors (TS and YC) or by discussion with a third author (RJT).

We pooled the proportion of newly diagnosed diabetes across studies with the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model. 21 The variances of the proportions were stabilized with the Freeman–Turkey Double Arcsine Transformation method. 22 The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the proportion in individual studies was calculated using the exact method. Heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using the Cochranʼs Q Test (P < .01 for heterogeneity) and Higgins I2 statistic (low: <25%, moderate: 25%‐50% and high: >50%). 23 To investigate the sources of between‐study heterogeneity, we performed a subgroup analysis by the country of origin of studies, and univariate random effects meta‐regression models 19 were fitted for mean age (median age was used if mean was not reported), sex (proportion of males) and sample size of studies. We did not assess for publication bias, as there were fewer than 10 studies in this meta‐analysis. 19 , 24 Analyses were performed using Stata software version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

A total of 148 studies were retrieved during the search, of which 100 studies were duplicates, and 30 were case reports, case series, letters, commentaries or review articles. After full‐text review, a further 10 studies were excluded, including three overlapping cohorts, three studies that were conducted only among patients with diabetes, and four that did not satisfy the criteria of newly diagnosed diabetes. A total of eight studies were included in the final analysis 4 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 (see Figure S2 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

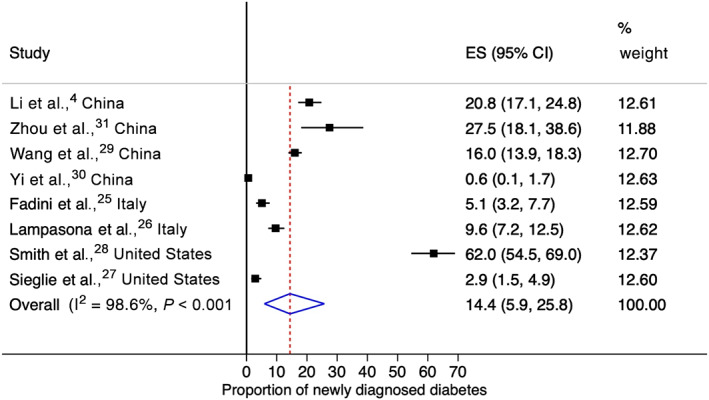

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies. All eight studies were retrospective cohort studies, consisting of four from China, 4 , 29 , 30 , 31 two from Italy 25 , 26 and two from the United States. 27 , 28 All studies were conducted during the first 5 months of the pandemic (i.e. January‐May 2020). The mean or median age of patients in these studies varied from 47 to 65.5 years. All the studies (except for two with no data on sex) 29 , 30 had more males than females, with the proportion of males ranging from 52.1% to 67.1%. Data on new‐onset diabetes were available in two studies 4 , 31 and three studies (or cohorts) had previously undiagnosed diabetes cases. 4 , 28 , 30 In six studies (or cohorts), 4 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 HbA1c was not performed for all participants, so it was not possible to differentiate between new‐onset and previously undiagnosed diabetes. In the majority of studies (n = 6), 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 the exact time of detection of newly diagnosed diabetes was not reported, whereas, in two studies, 4 , 29 the diagnosis was made within 24 hours to 3 days after hospital admission. Only one study reported on the type of diabetes (i.e. type 2 diabetes). 27 The quality of studies was either fair or good, with most (n = 6; 75%) studies being of good quality. With a total of 3711 COVID‐19 patients with 492 cases of newly diagnosed diabetes from eight studies, the random effects meta‐analysis estimated a pooled proportion of 14.4% (95% CI: 5.9%‐25.8%) with a high degree of heterogeneity (I2: 98.6%, P < .001) (Figure 1). The pooled proportion was non‐significantly lower in China than in other countries (13.4% vs. 15.4%, P = .87; Figure S3). Meta‐regression models found no significant association between the pooled proportion and mean study age (P = .84), the proportion of males (P = .89) and sample size (P = .81) (Table S2).

TABLE 1.

Study characteristics

| Author and country | Study design | Study period | Study setting | Age (y), mean (SD or range) or median (IQR) | Male, % | N a | n b (%) | Definition of newly diagnosed diabetes | Time of diagnosis | Type of diabetes | Study quality c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New‐onset diabetes | |||||||||||

|

Li et al., 4 China |

Retrospective cohort | 22 Jan‐17 Mar 2020 | Wuhan Union Hospital | 61 (49‐68) | 52.1 | 453 | 25 (5.5) | No prior diabetes history, FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L and HbA1c <6.5% | Within 3 d after hospital admission | NR | Good |

|

Zhou et al., 31 China |

Retrospective cohort | Jan‐Mar 2020 | Anhui Provincial Hospital | 47 (35‐56) | 60 | 80 | 22 (27.5) | No prior diabetes history, RBG ≥11.1 mmol/L and HbA1c<6.5% | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | NR | Good |

| Previously undiagnosed diabetes | |||||||||||

|

Li et al., 4 China |

Retrospective cohort | 22 Jan‐17 Mar 2020 | Wuhan Union Hospital | 61 (49‐68) | 52.1 | 453 | 38 (8.4) | No prior diabetes history, FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L and HbA1c ≥6.5% | Within 3 d after hospital admission | NR | Good |

|

Yi et al., 30 China |

Retrospective cohort | Jan‐Feb 2020 | Jinyintan Hospital in Wuhan, Ruijin Hospital in Shanghai, Tongren Hospital in Shanghai, and Tongling Peopleʼs Hospital in Anhui | NR | NR | 521 | 3 (0.6) | No prior diabetes history and HbA1c ≥6.5% | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | NR | Good |

| Smith et al., 28 United States | Retrospective cohort | 16 Mar‐2 May 2020 | Saint Barnabas Medical Center | 64.4 (range: 21‐100) | 53.3 | 184 | 85 (46.2) | No prior diabetes history and HbA1c ≥6.5% | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | NR | Fair |

| New‐onset or previously undiagnosed diabetes d | |||||||||||

|

Li et al., 4 China |

Retrospective cohort | 22 Jan‐17 Mar 2020 | Wuhan Union Hospital | 61 (49‐68) | 52.1 | 453 | 31 (6.8) | No prior diabetes history and FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L | Within 3 d after hospital admission | NR | Good |

| Wang et al., 29 China | Retrospective cohort | 24 Jan‐10 Feb 2020 | Wuhan Union West Hospital and Wuhan Red Cross Hospital | NR | NR | 1101 e | 176 (16.0) | No prior diabetes history and FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L | Within 24 h after hospital admission | NR | Fair |

| Fadini et al., 25 Italy | Retrospective cohort | Feb‐Apr 2020 | Hospital in North‐East Italy | 64.9 (15.4) | 59.3 | 413 | 21 (5.1) | No prior diabetes history, HbA1c ≥6.5% or RBG ≥11.1 mmol/L with signs and symptoms of hyperglycaemia | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | NR | Good |

| Smith et al., 28 United States | Retrospective cohort | 16 Mar‐2 May 2020 | Saint Barnabas Medical Center | 64.4 (range: 21‐100) | 53.3 | 184 | 29 (15.8) | No prior diabetes history, persistently elevated FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L and requiring insulin therapy | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | NR | Fair |

| Sieglie et al., 27 United States | Retrospective cohort | 11 Mar‐30 Apr 2020 | Massachusetts General Hospital | 63.9 (16.5) | 57.6 | 450 | 13 (2.9) | No prior diabetes history and HbA1c ≥6.5% or RBG ≥11.1 mmol/L | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | Type 2 diabetes | Good |

| Lampasona et al., 26 Italy | Retrospective cohort | 25 Feb‐19 Apr 2020 | IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital | 65.5 (55‐74.5) | 67.1 | 509 | 49 (9.6) | No prior diabetes history and mean FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L during hospitalization | Exact time of diagnosis not reported | NR | Good |

Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IQR, interquartile range; NR, not reported; RBG, random blood glucose; SD, standard deviation.

Number of COVID‐19 patients.

Number of newly diagnosed diabetes cases.

Study quality was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool.

HbA1c was not performed for all participants, so it was not possible to differentiate between new‐onset and previously undiagnosed diabetes.

157 patients who were transferred to another hospital were excluded.

FIGURE 1.

Forest plot for pooled proportion of newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID‐19 patients

While newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID‐19 patients could be attributed to the stress response associated with severe illness or treatment with glucocorticoids, the diabetogenic effect of COVID‐19 should also be considered. 3 This is supported by reports showing exceptionally high insulin requirements in severely or critically ill COVID‐19 patients with diabetes. These appear disproportionate when compared with critical illness caused by other conditions. 5 , 7 Further, it has been noted that diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state are unusually common in COVID‐19 patients with diabetes. 1 , 2 , 5 , 9 , 14 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the virus that causes COVID‐19, by attaching to angiotensin‐converting enzyme‐2 (ACE2) receptors in beta cells of the pancreas, could cause acute impairment in insulin secretion. 3 Indeed, an organoid study has shown that SARS‐CoV‐2 can enter and damage the pancreatic beta cells. 32 SARS‐CoV‐2 may also injure the beta cells by triggering a plethora of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin‐6) or by enhancing autoimmunity in genetically predisposed people. 3 In addition to defective insulin secretion, COVID‐19 patients also present with a high degree of insulin resistance, particularly those with severe illness. 5 It is not known whether this is because of insulin receptor defects in the key metabolic organs associated with glucose metabolism or interference with the insulin receptor signalling by the virus. ACE2 receptors are expressed in the liver, adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, and binding of SARS‐CoV‐2 to these receptors may impair responses to insulin. 3 The insulin receptor signalling could also be impaired by the pro‐inflammatory cytokines induced by SARS‐CoV‐2, or by enhanced actions of angiotensin II resulting from the downregulation of ACE2 after the virus enters the cells. 3 , 5 , 9 Similar mechanisms with other viral infections, such as hepatitis C, leading to type 2 diabetes, have been described previously. 33

This is the first systematic review and meta‐analysis to study the extent of newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID‐19 patients. We used robust and standard methods, and the search was comprehensive (including grey literature); the literature search, study screening, selection, data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by two researchers, and the quality of most studies was good. Finally, we removed overlapping cohorts from our analysis, a step not commonly performed in many other systematic reviews and meta‐analyses conducted in COVID‐19 patients. However, our study has some limitations. The true proportion is unknown as all studies were hospital‐based, and the patients were mostly severely or critically ill. Further, of the eight studies, 50% were from China, and the rest were from only two other countries, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the subgroup and meta‐regression analyses lack sufficient power to detect associations between variables, as they are limited to the use of study‐level data, and the number of studies was small. 19 , 24 These limitations clearly emphasize the need for more studies with larger samples, including those conducted in community settings where mild cases are treated, from several regions of the world.

In conclusion, this meta‐analysis of eight studies with more than 3700 patients shows a pooled proportion of 14.4% for newly diagnosed diabetes in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients. Recent reports have shown that newly diagnosed diabetes may confer a greater risk for poor prognosis of COVID‐19 than no diabetes or pre‐existing diabetes. 4 , 13 Therefore, COVID‐19 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes should be managed early and appropriately and closely monitored for the emergence of full‐blown diabetes and other cardiometabolic disorders in the long term.3, 34 In this regard, the establishment of the CoviDiab Registry (covidiab.e-dendrite.com) 2 is timely and should provide valuable insights into issues regarding COVID‐19‐related diabetes. We are now seeing a classic example of a lethal intersection between a communicable and a non‐communicable disease.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TS conceived the idea, conducted the literature search, screened, selected and assessed the quality of the articles, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NK reviewed and edited the manuscript. YC conducted the literature search and study screening, selection, data extraction and quality assessment; she also reviewed and edited the manuscript. RJT resolved any disagreements between TS and YC regarding the selection and quality assessment of the studies. RJT also helped TS in addressing the reviewersʼ comments and revising the manuscript. PZ conceived the idea along with TS and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supplementary file.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We deeply thank the reviewers for their time and valuable comments, which helped to improve this manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study

REFERENCES

- 1. Gentile S, Strollo F, Mambro A, Ceriello A. COVID‐19, ketoacidosis and new‐onset diabetes: are there possible cause and effect relationships among them? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:2507‐2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubino F, Amiel SA, Zimmet P, et al. New‐onset diabetes in Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(8):789‐790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sathish T, Tapp RJ, Cooper ME, Zimmet P. Potential metabolic and inflammatory pathways between COVID‐19 and new‐onset diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2020. 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li H, Tian S, Chen T, et al. Newly diagnosed diabetes is associated with a higher risk of mortality than known diabetes in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1897‐1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bornstein SR, Rubino F, Khunti K, et al. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID‐19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):546‐550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vas P, Hopkins D, Feher M, Rubino F, Whyte BM. Diabetes, obesity and COVID‐19: a complex interplay. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1892‐1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu L, Girgis CM, Cheung NW. COVID‐19 and diabetes: insulin requirements parallel illness severity in critically unwell patients. Clin Endocrinol. 2020;93:390‐393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Y, Li H, Zhang J, et al. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with diabetes and secondary hyperglycaemia with coronavirus disease 2019: a single‐centre, retrospective, observational study in Wuhan. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(8):1443‐1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Apicella M, Campopiano MC, Mantuano M, Mazoni L, Coppelli A, Del Prato S. COVID‐19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(9):782‐792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID‐19‐related mortality in England: a whole‐population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813‐822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh AK, Gillies CL, Singh R, et al. Prevalence of co‐morbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1915‐1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu J, Zhang J, Sun X, et al. Influence of diabetes mellitus on the severity and fatality of SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19) infection. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1907‐1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sathish T, de Mello GT, Cao Y. Is newly diagnosed diabetes a stronger risk factor than pre‐existing diabetes for COVID‐19 severity? J Diabetes. 2020. 10.1111/1753-0407.13125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li J, Wang X, Chen J, Zuo X, Zhang H, Deng A. COVID‐19 infection may cause ketosis and ketoacidosis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1935‐1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sathish T, Cao Y, Kapoor N. Newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID‐19 patients. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020. 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008‐2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Diabetes Association . 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical Care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S14‐S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.1 (updated September 2020). 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institutes of Health . Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- 21. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607‐611. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539‐1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta‐analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fadini GP, Morieri ML, Boscari F, et al. Newly‐diagnosed diabetes and admission hyperglycemia predict COVID‐19 severity by aggravating respiratory deterioration. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;168:108374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lampasona V, Secchi M, Scavini M, et al. Antibody response to multiple antigens of SARS‐CoV‐2 in patients with diabetes: an observational cohort study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(12):2548‐2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seiglie J, Platt J, Cromer SJ, et al. Diabetes as a risk factor for poor early outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2938–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith SM, Boppana A, Traupman JA, et al. Impaired glucose metabolism in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, and obesity is associated with severe COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.26227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang S, Ma P, Zhang S, et al. Fasting blood glucose at admission is an independent predictor for 28‐day mortality in patients with COVID‐19 without previous diagnosis of diabetes: a multi‐centre retrospective study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(10):2102‐2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yi H, Lu F, Jin X, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 infections among diabetics: a retrospective and multicenter study in China. J Diabetes. 2020;12:919‐928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou W, Ye S, Wang W, Li S, Hu Q. Clinical features of COVID‐19 patients with diabetes and secondary hyperglycemia. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang L, Han Y, Nilsson‐Payant BE, et al. A human pluripotent stem cell‐based platform to study SARS‐CoV‐2 tropism and model virus infection in human cells and organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27(1):125‐136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lecube A, Hernández C, Genescà J, Simó R. Glucose abnormalities in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(5):1140‐1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sathish Thirunavukkarasu, Cao Yingting. What is the role of admission HbA1c in managing COVID‐19 patients?. Journal of Diabetes. 2020. 10.1111/1753-0407.13140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supplementary file.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study