Abstract

Bipartisan governmental representatives and the public support investment in health care, housing, education, and nutrition programs, plus resources for people leaving prison and jail (Halpin, 2018; Johnson & Beletsky, 2020; USCCR, 2019). The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 banned people with felony drug convictions from receiving food stamps or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. Food insecurity, recidivism, and poor mental and physical health outcomes are associated with such bans. Several states have overturned SNAP benefit bans, yet individuals with criminal convictions are still denied benefits due to eligibility criteria modifications. COVID‐19 has impaired lower‐income, food‐insecure communities, which disproportionately absorb people released from prison and jail. Reentry support is sorely lacking. Meanwhile, COVID‐19 introduces immediate novel health risks, economic insecurity, and jail and prison population reductions and early release. Thirty to 50 percent of people in prisons and jails, which are COVID‐19 hotspots, have been released early (Flagg & Neff, 2020; New York Times, 2020; Vera, 2020). The Families First Coronavirus Response Act increases flexibility in providing emergency SNAP supplements and easing program administration during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights recommends eliminating SNAP benefit restrictions based on criminal convictions, which fail to prevent recidivism, promote public safety, or relate to underlying crimes. Policy improvements, administrative flexibility, and cross‐sector collaboration can facilitate SNAP benefit access, plus safer, healthier transitioning from jail or prison to the community.

Keywords: nutrition, equity, COVID, criminal justice

Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic has forcefully exposed the vast inequities that exist within our public health and social safety net systems.1 Scholars have traced how U.S. social welfare and criminal justice systems have governed socially marginal groups but also poverty itself (Sugie, 2012). The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that between 70 and 100 million adults in the United States have a criminal record (Goggins & DeBacco, 2018). People involved with the criminal legal system face significant health challenges prior to, during, and after incarceration, given that mass incarceration is a social‐structural driver of health inequity (Bowleg, 2020). These challenges are much more pronounced during a pandemic. Nearly 300,000 people in U.S. jails and prisons have been infected and 1,500 inmates and correctional officers have died due to COVID‐19 prior to the end of 2020 (New York Times, 2020). Some local and state decarceration efforts have included early release and jail and prison population reductions during the pandemic to decrease the risk of COVID‐19 transmission (Hawken, Mullins, Prueter, & Kulick, 2020; Vera, 2020).2 For instance, California and Kentucky reduced its jail population by 30 to 50 percent, whereas overall prison population reductions nationwide are less significant (Flagg & Neff, 2020; Vera, 2020). Postincarceration reentry is a vulnerable time when most people return to underresourced neighborhoods with limited means and dire needs for safety net programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) (Harding, Wyse, Dobson, & Morenoff, 2014; Western, 2018; Western, Braga, Davis, & Sirois, 2015).

Empirical evidence underscores the disproportionate effects of incarceration, food insecurity, and COVID‐19 among communities of color (Dickinson, 2019; Golembeski & Fullilove, 2008; Tai, Shah, Doubeni, Sia, & Wieland, 2020). Moreover, the intersecting and cumulative adverse consequences of these sociopolitical determinants affect individuals and households, which experience further material and emotional stress (Harding et al., 2014; Western, 2018; Dawes, 2020). Preincarceration factors, including poverty, structural racism, and health‐care access barriers; substandard health care within jails and prisons; and the health impacts of the carceral systems themselves compromise health and well‐being and facilitate the risk of further criminal legal system contact upon release. The increase in prisons and jails releasing or diverting populations combined with the economic, health, and social challenges of COVID‐19 may increase disproportionate health and economic burdens among communities with limited resources.

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) embodies the era's tough on crime and welfare reform ethos and welfare retrenchment alongside increases in incarceration (Sugie, 2012). PRWORA established a ban on states providing SNAP and TANF benefits to anyone with felony convictions related to drug use, possession, or distribution (NPHL, 2020; USCCR, 2019). Such collateral consequences of punishment, which impose burdens and barriers in the form of public benefit bans and restrictions based on a criminal conviction, compromise the health, well‐being, and safety of individuals and their communities, especially amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic (USCCR, 2019). Collateral consequences are: “formal legal and regulatory sanctions that the convicted bear beyond the sentence imposed by a criminal court; and the informal impacts of criminal [legal system] contact on families, communities, and democracy” (Kirk & Wakefield, 2018). The imposition of collateral consequences, which are often broad, vague, and subjective, on people with criminal convictions often fails to prevent recidivism, promote public safety, or relate to underlying crimes (Golembeski, 2020). Such is especially true regarding banning those with criminal convictions from receiving food assistance (NPHL, 2020; USCCR, 2019). This article focuses on the detrimental effects of denying SNAP benefits to individuals with felony convictions and the increased risks of food insecurity, which are especially heightened due to the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Food Insecurity and COVID‐19

The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life” (Gibson, 2012). Food insecurity is associated with increased risks for chronic disease and overall poorer health outcomes, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, depression, and iron deficiency, among pregnant people (Gregory & Coleman‐Jensen, 2017; Gundersen & Ziliak, 2015). Food insecurity decreases dietary intake quality and quantity and exacerbates stress, which can affect the immune system and contribute to overall poorer health outcomes (Gregory & Coleman‐Jensen, 2017; NPHL, 2020). As the severity of food insecurity increases, the likelihood of the development of chronic diseases also increases (Gregory & Coleman‐Jensen, 2017). Households near the federal poverty line, single‐parent households, individuals living alone, Black‐ and Latinx‐headed households, and formerly incarcerated individuals experience a higher prevalence of food insecurity (Coleman‐Jensen, Rabbitt, Gregory, & Singh, 2019; Testa & Jackson 2019, 2020). In 2015, the National Commission on Hunger reported populations with higher incarceration rates to experience higher rates of hunger and food insecurity (NCH, 2015).

Food insecurity rates are estimated to have more than doubled since the advent of the COVID‐19 pandemic when 11.1 percent of households (14.3 million households) were food insecure in 2018 (Bauer, 2020; Coleman‐Jensen et al., 2019). Data from the U.S. Census Bureau's 2020 COVID‐19 Household Pulse Survey from April 23 to June 30, 2020, reported that 25.2 percent of respondents experienced food insecurity, with differences based upon racial and ethnic groups with 34.8 percent of Black respondents, 33.3 percent of Hispanic/Latinx respondents, 22.2 percent of Asian respondents reported experiencing food insecurity compared with 21.2 percent of White respondents (Schanzenback & Tomeh, 2020).3 COVID‐19 conditions have stretched food bank lines for miles, with more U.S. households relying on food banks to meet nutritional needs (Charles, 2020). In addition, food system supply chain constraints have contributed to grocery store shortages, food waste, and rising food prices (Charles, 2020; Nestle, 2019; Nord, Coleman‐Jensen, & Gregory, 2014). Higher food prices are also associated with increased levels of food insecurity, particularly for SNAP benefit recipients (Nestle, 2019; Nord et al., 2014). COVID‐19 has exacerbated previously vast economic and food insecurities, which may also heighten the risk of COVID‐19‐related complications or death (Bauer, 2020; Laviano, Koverech, & Zanetti, 2020).

SNAP Policies

The federal government funds the SNAP program to address food insecurity and improve nutrition, while states contribute to the administrative costs and program administration (Dickinson, 2019). Despite the minimal support of $1.40 per person per meal on average (CBPP, 2019), the SNAP benefits not only support low‐income households in crisis but also expediently inject monetary resources into the economy as an effective form of economic stimulus (Bauer & Whitmore Schanzenbach, 2020; Nestle, 2019; Rosenbaum, Bolen, Neuberger, & Dean, 2020). The Families First Coronavirus Response Act provides emergency SNAP benefits as part of increasing food assistance for struggling families, managing rising administrative demands, and ensuring that participants maintain much‐needed benefits during the pandemic (CBPP, 2020). For instance, the Act enables states to verify eligibility and administer SNAP benefits without in‐person interviews in light of safety and health concerns and social distancing during the pandemic (CBPP, 2020).

Two SNAP policies contribute to collateral consequences for people with a criminal conviction: the SNAP ban and work requirements. During the 1990s, PRWORA established a ban on states providing SNAP and TANF benefits to anyone with felony convictions related to “fleeing” felons avoiding retribution from committing a felony or violating the terms of their probation or parole; those who have committed welfare fraud by applying for benefits in multiple states; and those convicted of felonies for possession, use, or distribution of illegal drugs (NPHL, 2020; USCCR, 2019).

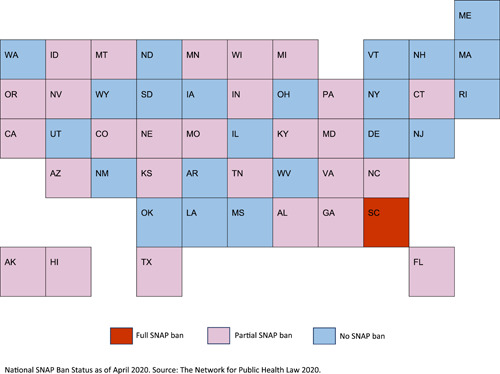

Some states recognize these policy relics of the War on Drugs have deleterious impacts, such as recidivism, food insecurity, and poor mental and physical health outcomes (Testa & Jackson 2019; Tuttle, 2019; Yang, 2017). In turn, several states have either overturned or modified these bans. South Carolina is the only remaining state to impose a lifetime ban on SNAP benefits for those convicted of drug‐related felonies (NPHL, 2020; Wolkomir, 2018). Twenty‐two states and Washington, DC have completely opted out of the ban, whereas 27 states have modified the ban so that qualifying people with drug felony convictions are still eligible to receive SNAP benefits (NPHL, 2020). Michigan, along with four other states, permanently deny anyone with two or more felony drug convictions SNAP benefits (NPHL, 2020). Moreover, Pennsylvania reverted to a modified ban in 2018 after a no‐ban phase as a reported effort to minimize perceived misuse of SNAP benefits (NPHL, 2020). In 2018, Governor Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania signed a bill banning those with felony drug convictions from receiving public benefits for ten years (Quinn, 2019) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

National SNAP Ban Status (U.S. Map).

The Trump administration's latest proposed rule in 2019, which was ultimately vacated by a federal judge, would have made it more difficult for states to waive a work requirement stipulating “able‐bodied” adults without children work at least 20 hours a week or else lose their SNAP benefits after 3 months (Chappell, 2020). SNAP benefit eligibility associated with time limits and work requirements renders the underemployed or informally employed people with prior convictions, especially vulnerable to food insecurity (Dickinson, 2019; Wolkomir, 2018). A weaker economy, a competitive labor market, parole and benefit eligibility requirements, employment barriers, such as stigma and discrimination, as well as physical and health challenges associated with incarceration combine to inordinately penalize people involved with the criminal legal system. Moreover, states may not provide individuals with work or training program opportunities and stop benefits regardless of how diligently individuals are looking for work.

Federal law allows states to exempt some individuals from the work requirements and suspend the three‐month limit, but states must proactively do so by drafting and submitting a waiver (Wolkomir, 2018). The work requirement will make it exceptionally challenging for people with felony convictions to receive SNAP benefits, especially with social distancing and fewer employment opportunities during the pandemic.

Previously, bipartisan members of Congress rejected similar cuts in the 2018 Farm Bill. Although a federal judge issued an injunction halting the Trump administration's SNAP proposed work requirement rule change in March 2020, the potential fate of this food safety net program is largely uncertain beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic (Dilawar, 2020). Policy experts advocate for increasing food and economic security and stimulus amidst COVID‐19 by increasing SNAP maximum benefit levels, waiving all work requirements, maintaining state flexibility for category eligibility, and expanding overall eligibility for some vulnerable populations (Bauer & Whitmore Schanzenbach, 2020; CBPP, 2020; Rosenbaum et al., 2020). Ingenuity is imperative during emergencies, such as economic depression and a pandemic, which renders millions vulnerable and deprives the economy of necessary stimulus. Such innovation and flexibility should also be seriously considered beyond the scope of these major events and in light of the increased need of individuals and populations, such as those recently released from prison and jail. Ultimately, offering supports for economic stability further upstream will reduce long‐term and exorbitant burdens on the health and social safety net.

Health, Social, and Economic Consequences of Criminal Legal System Involvement

The federal prison population has increased by 790 percent between the early 1980s and 2018, with a tenfold rise in the number of drug‐related convictions (The Sentencing Project, 2020). Black people have been incarcerated at rates five to seven times higher than Whites and face disproportionately punitive sentencing and collateral consequences (Carson & Sabol, 2012; Rosenberg, Groves, & Blankenship, 2017). Moreover, over 80 percent of women are in jail for nonviolent offenses and struggle with mental health and substance use challenges (Swavola, Riley, & Subramanian, 2016).

Incarceration itself contributes to malnutrition and poor health outcomes for an already medically vulnerable population due to poor nutrition and diet, an elevated risk of violence, and the mental health repercussions of crowding, poor sanitation, and prolonged isolation (Cloud, Drucker, Browne, & Parsons, 2015; Hannan‐Jones & Capra, 2016; Venters, 2019). Despite limited studies on the adequacy of diet and food practices within carceral contexts, nutritional standards at local and state institutions, which vary widely, are influenced by disparate laws, policies, and court outcomes (Hannan‐Jones & Capra, 2016; Santo & Iaboni, 2015). Within prisons, there are higher rates of obesity, which is associated with type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cancer, in comparison to the general population (CDC, 2020; Maruschak, Berzofsky, & Unangst, 2016). Notably, infectious and noncommunicable diseases that are adversely affected by inadequate nutrition are also more common among incarcerated people, including human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and neurological conditions (Herbert, Plugge, Foster, & Doll, 2012; Leach & Goodwin, 2014).

More than 10,000 individuals are released from federal and state prisons and 200,000 churns through jails weekly (Carson, 2020; Flagg & Neff, 2020). Nearly 95 percent of incarcerated individuals will return to their communities and face reentry challenges and stressors as part of restoring relationships, along with accessing health care, adequate food, safe housing, and financial security (Binswanger, Redmond, Steiner, & Hicks, 2012; Golembeski & Fullilove, 2008; Western, 2018). Over 44,000 collateral consequences of punishment involve health, employment, housing, debt, civic involvement, voting rights, families, and communities, which further limit self‐sufficiency absent of less healthy relationships (CSG, 2020; Hersch & Meyers, 2018; Kirk & Wakefield, 2018). Over 100 SNAP‐related bans, barriers, and restrictions, which are indirect consequences of a criminal conviction, exist nationwide (CSG, 2020). Moreover, many convicted individuals are not aware of such sanctions, given that judges and attorneys are not required to provide such information (USCCR, 2019). Numerous studies confirm the immediate aftermath of release is a particularly vulnerable period—a worsening of chronic medical conditions and substance use, plus a high risk of hospitalization and even death (Binswanger et al., 2012, 2014; Meyer et al., 2014).

Upon release from prison or jail, the majority of people return to underresourced neighborhoods in which poverty, violence, substance use, food insecurity, and criminal legal system contact are prevalent because of structural issues (Binswanger et al., 2011; Golembeski & Fullilove, 2008). The current COVID‐19 crisis intensifies the numerous health challenges and structural barriers, such as unemployment, facing poorer people and people of color, including individuals released from prison and jail (Tai et al., 2020; Wright & Merritt, 2020, Rosenbaum, Dean, & Neuberger, 2020). Unemployment rates have reached all‐time highs during COVID‐19, making financial security less obtainable for people with criminal convictions, thus increasing the risk of food insecurity. Prior to the pandemic, the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated individuals was 30 percent or five times higher than the general population, which surpassed U.S. unemployment rates during the Great Depression (Couloute & Kopf, 2018).

Research on whether Ban the Box policies are working as intended in removing hiring biases toward those with criminal records is mixed, yet most employers perform criminal background checks in hiring (Agan & Starr, 2018; Doleac & Hansen, 2020). Some suggest Ban the Box policies may be harmful to formerly incarcerated individuals but also people of color without convictions because employers may statistically discriminate and use other imperfect information to guess who might have a criminal record (Doleac & Hansen, 2020). Nevertheless, a seminal study revealed that Black men without criminal records were less likely than white men with records to receive callbacks after applying for jobs (Pager, 2003). Only 55 percent of individuals released from prison have any earnings, and those with employment often earn less than minimum wage (Looney & Turner, 2018). Black women, who have been formerly incarcerated, face even higher rates of unemployment and also bear greater income‐related burdens (Binswanger et al., 2011; Hersch & Meyers, 2018; Meyer et al., 2014). Approximately 60 to 80 percent of incarcerated women have minor children, and most are single parents (Hersch & Meyers, 2018; Owen, Wells, & Pollock, 2017; Swavola et al., 2016).

Several studies have established an association between SNAP‐related bans and increased risks of recidivism, poor mental and physical health outcomes, and food insecurity (Tuttle, 2019; Yang, 2017). Bruce Western's research on the first year after people were released from prison in Massachusetts found a median annual income of approximately $6,500 (2018). Significantly, the SNAP enrollment rate at two months was 70 percent but only 40 percent at year‐end, which Western attributes to SNAP's role as a crucial safety net supporting stabilization and successful entry into the labor market (Western, 2018). Food and economic safety nets and fair wage employment opportunities are critical to equitable reentry support systems (Gamblin, 2018). Low wage employers may benefit most from welfare reform since they may offer below subsistence salaries to a desperate labor pool forced to resort to SNAP benefits to supplement an inadequate income (Dickinson, 2019). Women and children constitute the greatest recipients of SNAP benefits as well as the greatest casualties of wage discrimination and policies that are overly punitive in contrast to those prioritizing treatment, care, and support (Dickinson, 2019; Herd & Moynihan, 2019; Western, 2018).

The pandemic has exacerbated the adverse social, economic, and health‐related effects associated with mass incarceration. Food insecurity, substandard housing and schools, a lack of paid leave, and a livable wage comprise hallmarks of an alternate form of social distancing that profoundly impacts individuals, families, and communities involved with the criminal legal system. Lower‐income individuals, families, and communities bear disproportionate burdens of punishment's collateral consequences, including limitations on accessing SNAP and other public benefits (Harding, Morenoff, & Wyse, 2019; Wolkimir, 2018, Williams, Mechanic, Rogut, Colby, & Knickman, 2005).

Criminal Legal System Involvement and SNAP Benefit Access

SNAP provides nutrition benefits to supplement the food budgets of people in need, so they may purchase healthy food for a nutritionally adequate diet (NPHL, 2020). A strong social safety net and reentry supports for formerly incarcerated people are important factors in decreasing food insecurity, particularly for people with lower capacities for traditional employment (Western, 2018). One study of recently released individuals in Texas, Connecticut, and California found 91 percent of formerly incarcerated people reported food insecurity with no variation based on time of release (Wang et al., 2013). Negative impacts of incarceration relate to employment and income, education outcomes, food security (Cox & Wallace, 2016; Turney, 2015). Moreover, an increased likelihood of food insecurity, as well as other negative behavioral and early life consequences, exists among children of incarcerated parents (Davison et al., 2019; Sugie, 2012; Testa & Jackson, 2020; Turney, 2015).

Analyzing Fragile Families data, Sugie (2012) finds that those children with parents who have been incarcerated have a 1.68 times higher odds of receiving SNAP or food stamps in comparison to those families without parental incarceration. Access to nutritious, healthy food is a serious concern for people recently released from prison or jail or under community supervision (Dong, Tang, Stopka, Beckwith, & Must, 2018; Middlemass, 2019; Testa & Jackson, 2019, 2020; Wang et al., 2013). Given the high rates of comorbid chronic conditions and malnutrition among incarcerated populations, good nutrition is critical for the short‐ and long‐term health and well‐being of people reentering society (Binswanger et al., 2011, 2012; Binswanger, Mueller, Beaty, Min, & Corsi, 2014; Meyer et al., 2014; Middlemass, 2019; Wolkomir, 2018). Ultimately, several studies have found that SNAP lifetime bans are associated with increased risks of recidivism, food insecurity, and poor mental and physical health outcomes (Testa & Jackson, 2019, 2020; Tuttle, 2019; Yang, 2017).

As a consequence of then‐President Clinton and Congress’ welfare reform priorities of the 1990s, many people with felony drug convictions still face lifetime or modified bans on SNAP benefits. The current SNAP‐related bans targeting certain felony convictions disproportionately affect people of color and with low incomes, yet do not relate to the primary crimes or public safety goals (Kirk & Wakefield, 2018; NPHL, 2020; Tuttle, 2019; Wolkomir, 2018). These bans, barriers, and punishments rely on nonstandardized assessments of moral character rather than economic need criteria and incur additional red tape. States are required to affirmatively enact legislation in order to opt‐out of the ban or modify time periods and other elements (USCCR, 2019). Additionally, lack of clarity regarding eligibility and benefit purchase allowances; in‐person interviews, recertification processes, drug tests; and stigma in accessing and using benefits contribute to additional psychological costs (Blair & Starke, 2017; Herd & Moynihan, 2019).

Three common modifications to the SNAP felony ban are drug treatment, drug testing, and parole compliance. Fifteen states require drug treatment, nine states necessitate drug testing, and 16 states require parole condition compliance (NPHL, 2020). Permanent disqualification after multiple convictions or distribution of felony convictions is in place in certain states. Additionally, Kentucky and Nevada have adopted novel modifications to the federal ban in creating an exception for otherwise eligible pregnant people (NPHL, 2020). Over half of female federal prisoners’ sentences involve drug trafficking, making women, who are often also mothers, extremely vulnerable to adverse consequences of SNAP bans (Turney, 2015; Zeng, 2020). Overall, research evidence supports the repeal of statutory bans from nutrition‐related federal support programs while people are reentering society after incarceration for positive population health outcomes (Davison et al., 2019; McDonough, Ian, & Millimett, 2019; Tuttle, 2019; USCCR, 2019; Yang, 2017).

Very few jails and prisons enable SNAP benefit enrollment prior to release, which may limit immediate food access upon reentry (Wolkomir, 2018). Moreover, people often leave jail and prison with inadequate identification necessary for obtaining public benefits and other services. Easing and expediting SNAP benefit access, including before one leaves prison and jail, allows individuals to address other priorities associated with reentry and may minimize stressors. In South Dakota and New York City, people in prison and jail may file their SNAP benefit applications prior to release and have them accepted and processed (Wolkomir, 2018). Furthermore, reentry support services are inadequate absent of COVID‐19, disproportionately endangering the safety and well‐being of people diverted or released from jail and prison (Binswanger et al., 2014; Meyer et al., 2014). Food and economic security infrastructure, namely SNAP and TANF, are critical to equitable reentry support systems. Amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic, which is a time of increased need, effective and quick responses in reducing administrative burdens and increasing SNAP supplements further protect families from hardship and hunger (CBPP, 2020; Dickinson, 2019; Herd & Moynihan, 2019).

People who may face SNAP benefit restrictions as a result of convictions deserve the same right to food and food security. Strengthening the social safety net and eliminating benefit restrictions affecting individuals with criminal convictions aligns with recognizing the right to food as binding international law in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Ayala & Meier, 2017). The bipartisan U.S. Commission on Civil Rights calls on Congress to eliminate TANF and SNAP benefit restrictions based on criminal convictions and to require courts to give comprehensive notice of federal restrictions on individuals’ rights before guilty plea entry, upon conviction, and upon release (USCCR2019).

The Food Safety Net and Collateral Consequences Amidst COVID

COVID‐19 continues to ravage communities globally. In the United States, this pandemic will indelibly compromise the health and well‐being of many, especially lower‐income people with involvement in the criminal legal system. As COVID‐19 sweeps across the nation, the unemployment rate has reached a record high of 14.7 percent (23.1 million) in April 2020, which is a 10.3 percent increase since the pandemic's onset (Bureau, 2020). People of color experience a higher burden of unemployment and face greater challenges in adequately quarantining at home, which may contribute to racial disparities in COVID‐19 mortality and morbidity rates (Bureau, 2020; Hooper, Anna Maria, & Perez‐Stable, 2020). These strikingly high rates of income loss, particularly for lower‐income people, are associated with a marked increase in food insecurity (Jordan, 2020; Nord et al., 2014). A more competitive job market, economic decline, and novel health risks will intensify challenges associated with securing employment, such as discrimination and stigma, particularly for people with a criminal conviction.

The majority of U.S. voters support policies that invest in economic security, including those focusing on people that have been incarcerated, and oppose recent Congressional proposals to reduce health care, housing, education, and nutrition programs (Halpin, 2018; Johnson & Beletsky, 2020). States might benefit in leveraging administrative flexibility to extend and sustain nutrition‐related federal support to all vulnerable constituents, given the underserved areas to which formerly incarcerated people return and the health, economic, and employment crises associated with the pandemic whereby more people are being diverted from or released from jail or prison. Moreover, congressional elimination of SNAP benefit restrictions based on criminal convictions, which fail to prevent recidivism, promote public safety, or relate to underlying crimes, can usher in standardized policy change designed to eliminate unnecessarily punitive burdens, barriers, and punishments. Indeed, future research will help elucidate the extent to which the COVID‐19 pandemic and associated policy decisions influence food security among people with criminal legal system contact.

States have recently leveraged the Families First Coronavirus Response Act's malleability to expand food assistance amidst novel health and economic crises associated with the epidemic (Rosenbaum et al., 2020). Such innovative and pliable policy adjustments might alleviate the inequities that contribute toward arrest and incarceration as well as susceptibility to COVID‐19 infection and food insecurity. States have the capacity to individually opt‐out of federally imposed SNAP‐related bans from the 1990s without any funding loss or reductions and Congress can repeal all “punitive mandatory consequences that do not serve public safety, bear no rational relationship to the offense committed, and impede people convicted of crimes from safely reentering and becoming contributing members of society” (USCCR, 2019).

Prohibiting people convicted of crimes from accessing nutritional assistance benefits conflicts with the goals of rehabilitation, successful reentry, and enhancing public safety. The COVID‐19 crisis intensifies the numerous challenges and barriers facing people being released from prison and jail. A strong social safety net, support for reentry, and reexamination of many of the unnecessary criminal conviction‐related penalties around public benefits are critical for safer, healthier transitions from prisons and jails to communities.

Conclusion

Incarceration, widely recognized as a cause and consequence of poverty, shapes structural aspects of racial and class inequities (Sugie, 2012; Western, 2018). Employment barriers, intergenerational effects, and related health and recidivism risks are associated with returning to communities upon release (Binswanger et al., 2012; Venters, 2019; Western, 2018). Although the relationship between incarceration and food insecurity may be complex, researchers provide further evidence that incarceration leads to an increase in food insecurity for individuals and their families (Cox & Wallace, 2016; McDonough et al., 2019; Middlemass, 2019; Turney, 2015; Wang et al., 2013; Western, 2018). A strong social safety net for people involved with the criminal legal system is key to improving health as well as economic outcomes, particularly for those most marginalized (Binswanger et al., 2011; Harding et al., 2014; Western, 2018). COVID‐19 and related health and economic strains, plus the restrictions faced by people released from prison and jail, necessitate greater expansion of safety net programs, such as SNAP (Bauer, 2020; Dilawar, 2020; Johnson & Beletsky, 2020; Testa & Jackson, 2019, 2020; Wright & Merritt, 2020).

Many policymakers, researchers, practitioners, politicians, and advocates support bipartisan criminal legal system reform efforts, such as alternatives to incarceration, drug policy reform, and decarceration, alongside addressing mass incarceration's collateral consequences, such as food insecurity (Johnson & Beletsky, 2020; USCCR, 2019). The flexibility of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act to provide emergency SNAP supplements and ease program administration during the pandemic combined with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights calls for Congress to eliminate SNAP benefit restrictions based on criminal convictions provide critical, timely guidance. Remaining SNAP bans and restrictions, which do not enhance public safety or rationally relate to original offenses, impede people with criminal convictions from safely and successfully reentering society. The COVID‐19 pandemic has opened the Overton Window in framing social safety net reforms as acceptable policy positions across the criminal legal system. Policy improvements, nondiscrimination, and cross‐sector collaboration are critical to ensure expedient access to SNAP benefits and to best support healthier, safer transitions from jail or prison to the community upon release.

Biographies

Cynthia A. Golembeski, MPH, is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholar pursuing a JD/PhD in Law and Public Administration at Rutgers University, who uses mixed methods to research how policy, law, public management, and citizen‐state relations operate at the intersection of criminal legal and health systems.

Ans Irfan, MD, MPH, FRSPH, is Director of Policy & Programming with the DrPH Coalition, an Adjunct Professor at the Milken Institute School of Public Health, and a Health Policy Research Scholar with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation with a focus on the translation of science into policy and programs for global health equity.

Kimberly R. Dong, DrPH, MS, RD, LDN, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine, conducts mixed methods research examining the causes and consequences of food insecurity and poor health‐care access among people with HIV and individuals involved with the criminal legal system.

SNAP and TANF restrictions provide a useful window into the insidious and spiteful nature of some collateral consequences of criminal convictions. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2019.

Notes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Corresponding author: Cynthia A. Golembeski, cag348@rutgers.edu

Criminal legal system‐people include adults serving sentences in prisons and jails, awaiting trial or sentencing, and people under community supervision, such as parole and probation. We try to use person first and nonstigmatizing or pejorative language (Tran et al., 2018; Broyles et al., 2014).

Jails are typically short‐term holding facilities under local jurisdiction for the newly arrested, those awaiting trial or sentencing, and those serving short sentences. State or federal prisons are institutional facilities where people who are convicted serve longer sentences.

Food insecurity in this survey was measured by food insufficiency asking respondents, “Getting enough food can also be a problem for some people. Which of these statements best describes the food eaten in your household before March 13, 2020?” with response options: “Enough of the kinds of foods (I/we) wanted to eat,” “Enough, but not always the kinds of foods (I/we) wanted to eat,” “Sometimes not enough to eat,” and “Often not enough to eat.”

References

- Agan, Amanda , and Starr Sonja. 2018. “Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A Field Experiment*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (1): 191–235. 10.1093/qje/qjx028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, Ana , and Mason Meier Benjamin. 2017. “A human rights approach to the health implications of food and nutrition insecurity.” Public Health Reviews 38 (1): 1–22. 10.1186/s40985-017-0056-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Lauren . 2020. The COVID‐19 Crisis Has Already Left Too Many Children Hungry in America. Washington, DC: Brookings; https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19-crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/. Accessed September 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Lauren , and Whitmore Schanzenbach Diane. 2020. Food Security is Economic Security is Economic Stimulus.” The Hamilton Project (March 09). [Online]. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/blog/food_security_is_economic_security_is_economic_stimulus?_ga=2.116815106.503659666.1595801945-193282667.1586742085

- Binswanger, Ingrid A. , Mueller Shane R., Beaty Brenda L., Min Sung‐joon, and Corsi Karen F.. 2014. “Gender and Risk Behaviors for HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections among Recently Released Inmates: A Prospective Cohort Study.” AIDS Care 26 (7): 872–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, Ingrid A. , Nowels Carolyn, Corsi Karen F., Long Jeremy, Booth Robert E., Kutner Jean, and Steiner John F.. 2011. “From the Prison Door Right to the Sidewalk, Everything Went Downhill. A Qualitative Study of the Health Experiences of Recently Released Inmates.” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 34 (4): 249–55. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, Ingrid A. , Redmond Nicole, Steiner John, and Hicks Le. Roi. 2012. “Health Disparities and the Criminal Justice System: An Agenda for Further Research and Action.” Journal of Urban Health 89 (1): 98–107. 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Robert F. , and Anthony M. Starke, Jr . 2017. “The Emergence of Local Government Policy Leadership: A Roaring Torch or a Flickering Flame?” State and Local Government Review 49 (4): 275–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, Lisa . (2020). Reframing Mass Incarceration as a Social‐Structural Driver of Health Inequity. American Journal of Public Health, 110, (S1), S11–S12. 10.2105/ajph.2019.305464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles, Lauren M. , Binswanger Ingrid A., Jenkins Jennifer A., Finnell Deborah S., Faseru Babalola, Cavaiola Alan, Pugatch Marianne, and Gordon Adam J.. 2014. “Confronting Inadvertent Stigma and Pejorative Language in Addiction Scholarship: A Recognition and Response.” Substance Abuse 35 (3): 217–21. 10.1080/08897077.2014.930372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2020. “The Employment Situation” April 2020. USDL‐20‐0815. [Online]. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

- Carson, E. Ann . 2020. “Prisoners in 2018.” U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 253516. [Online]. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p18.pdf

- Carson, E. Ann , and Sabol William J. 2012. “Prisoners in 2011.” U.S. Department of Justice: Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 239808. [Online]. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p11.pdf

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . 2019. “Chart Book: SNAP Helps Struggling Families Put Food On the Table.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. [Online]. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/chart-book-snap-helps-struggling-families-put-food-on-the-table. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . 2020. “Most States Are Using New Flexibility in SNAP to Respond to COVID‐19 Challenges.” [Online]. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/most-states-are-using-new-flexibility-in-snap-to-respond-to-covid-19

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . 2020. “The Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity.” [Online]. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html

- Chappel, Bill . 2020. “Court Vacates Trump Administration Rule That Sought to Kick Thousands Off Food Stamps.” National Public Radio National. https://www.npr.org/2020/10/19/925497374/court-vacates-trump-administration-rule-that-sought-to-kick-thousands-off-food-s. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Charles, Dan . 2020. “Food Banks Get the Love, But SNAP Does More to Fight Hunger.” National Public Radio The Salt (May 22). https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2020/05/22/859853877/food-banks-get-the-love-but-snap-does-more-to-fight-hunger

- Cloud, David H. , Drucker Ernest, Browne Angela, and Parsons Jim. 2015. “Public Health and Solitary Confinement in the United States.” American Journal of Public Health 105 (1): 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman‐Jensen, Alisha , Rabbitt Matthew P., Gregory Christian A., and Singh Anita. 2019. “Household Food Security in the United States.” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service; Economic Research Report No. (ERR 270). 270.

- Couloute, Lucius , and Kopf Daniel. 2018. “Out of Prison and Out of Work: Unemployment among Formerly Incarcerated People.” Prison Policy Initiative (July). https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html

- Cox, Robynn , and Wallace Sally. 2016. “Identifying the Link Between Food Security and Incarceration.” Southern Economic Journal 82 (4): 1062–77. 10.1002/soej.12080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, Karen M. , D'Andreamatteo Carla, Markham Sabina, Holloway Clifford, Marshall Gillian, Smye Victoria L., and Davison Karen M.. 2019. “Food Security in the Context of Paternal Incarceration: Family Impact Perspectives.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (5): 776 10.3390/ijerph16050776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, Daniel E. 2020. The Political Determinants of Health. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/political-determinants-health [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, Maggie . 2019. Feeding the Crisis: Care and Abandonment in America's Food Safety Net, Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dilawar, Arvind . 2020. “Trump's Cuts to Food Stamps Almost Made the Pandemic Worse.” The Nation (April 01). https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/trump-food-stamps/

- Doleac, Jennifer L. , and Hansen Benjamin. 2020. “The Unintended Consequences of ‘Ban the Box’: Statistical Discrimination and Employment Outcomes When Criminal Histories Are Hidden.” Journal of Labor Economics 38 (2): 321–74. 10.1086/705880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Kimberly R. , Tang Alice M., Stopka Thomas J., Beckwith Curt G., and Must Aviva. 2018. “Food Acquisition Methods and Correlates of Food Insecurity in Adults on Probation in Rhode Island.” PLoS One 13 (6): e0198598 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0198598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagg, Anna , and Neff Joseph. 2020. “Why Jails Are So Important in the Fight Against Coronavirus.” The New York Times (March 31). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/upshot/coronavirus-jails-prisons.html

- Gamblin, Marlysa D. 2018. “Mass Incarceration: A Major Cause of Hunger.” Briefing Paper. Washington, DC: Bread for the World Institute. February. https://www.bread.org/sites/default/files/downloads/briefing-paper-mass-incarceration-february-2018.pdf

- Gibson, Mark . 2012. “Food Security—A Commentary: What Is It and Why Is It So Complicated?” Foods 1 (1): 18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggins, Becki R. , and DeBacco Denis A.. 2018. “Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, 2016: A Criminal Justice Information Policy Report.” United States Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Online]. http://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/abstract.aspx?ID=273696

- Golembeski, Cynthia . 2020. “Being convicted of a crime has thousands of consequences besides incarceration – and some last a lifetime”. The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/being-convicted-of-a-crime-has-thousands-of-consequences-besides-incarceration-and-some-last-a-lifetime-139192

- Golembeski, Cynthia , and Fullilove Robert. 2008. “Criminal (In)justice in the City and Its Associated Health Consequences.” American Journal of Public Health 98 (9 Suppl): S185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Christian A. , and Coleman‐Jensen Alisha 2017. “Chronic Disease, and Health Among Working‐Age Adults.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, ERR No. 235.

- Gundersen Craig, Ziliak James P. (2015). Food Insecurity And Health Outcomes. Health Affairs, 34, (11), 1830–1839. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, John . 2018. “Ensuring Basic Living Standards for All: Voter Attitudes Toward Government Assistance and Social Insurance Programs in the Trump Era.” March 07. Center for American Progress. [Online]. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2018/03/07/447412/ensuring-basic-living-standards/

- Hannan‐Jones, Mary , and Capra Sandra. 2016. “What Do Prisoners Eat? Nutrient Intakes and Food Practices in a High‐Secure Prison.” British Journal of Nutrition 115 (8): 1387–96. 10.1017/S000711451600026X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, David J. , Wyse Jessica J. B., Dobson Cheyney, and Morenoff Jeffrey D.. 2014. “Making Ends Meet after Prison.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 33 (2): 440–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, David J. , Morenoff Jeffrey D., and Wyse Jessica J.. 2019. On the Outside: Prisoner Reentry and Reintegration, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, Angela , Mullins Sandy, Prueter Janelle, and Kulick Jonathan. 2020. “Recommendations for Rapid Release and Reentry During the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” New York University Marron Institute of Urban Management. https://marroninstitute.nyu.edu/papers/recommendations-for-rapid-release-and-reentry-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- Herbert Katharine, Plugge Emma, Foster Charles, Doll Helen (2012). Prevalence of risk factors for non‐communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. The Lancet, 379, (9830), 1975–1982. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60319-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd, Pamela , and Moynihan Donald P.. 2019. Administrative Burden: Policymaking By Other Means, New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hersch, Joni , and Meyers Erin H.. 2018. “The Gendered Burdens of Conviction and Collateral Consequences on Employment.” Journal of Legislation 45: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, Monica Webb , Anna Maria Napoles, and Perez‐Stable Eliseo J.. 2020. “COVID‐19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” Journal of the American Medical Association 323: 2466 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sterling , and Beletsky Leo. 2020. “Helping People Transition From Incarceration to Society During a Pandemic. Health in Justice Action Lab.” Data for Progress, and Justice Collaborative Institute. May. [Online]. https://tjcinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/challenges-of-reentry-during-coronavirus.pdf

- Jordan, Rob . 2020. “COVID‐19 Could Exacerbate Food Insecurity Around the World.” Stanford Expert Warns. Stanford News https://news.stanford.edu/2020/05/05/covid-19-related-food-insecurity/

- Kirk, David , and Wakefield Sara. 2018. “Collateral Consequences of Punishment: A Critical Review and Path Forward.” Annual Review of Criminology 1 (1): 171–94. [Google Scholar]

- Laviano, Alessandro , Koverech Angela, and Zanetti Michela. 2020. “Nutrition Support in the Time of SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19).” Nutrition 74: 110834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach, B. , and Goodwin S.. 2014. “Preventing Malnutrition in Prison.” Nursing Standard (2014+) 20: 50–6, 10.7748/ns2014.01.28.20.50.e7900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looney, Adam , and Turner Nicholas. 2018. Work and Opportunity Before and After Incarceration. The Brookings Institute; https://www.brookings.edu/research/work-and-opportunity-before-and-after-incarceration/ [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak, Laura M. , Berzofsky, Marcus , and Unangst, Jennifer . 2016. “Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates” 2011‐2012 (No. NCJ 248491). Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Online]. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf

- McDonough, Ian. K. , and Millimet Daniel L.. 2019. “Criminal Incarceration, Statutory Bans on FoodAssistance, and Food Security in Extremely Vulnerable Households: Findings from a Partnership with the North Texas Food Bank.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 41 (3): 351–69. 10.1093/aepp/ppz011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Jaimie P., Zelenev Alexei, Wickersham Jeffrey A., Williams Chyvette T., Teixeira Paul A., Altice Frederick L. (2014). Gender Disparities in HIV Treatment Outcomes Following Release From Jail: Results From a Multicenter Study. American Journal of Public Health, 104, (3), 434–441. 10.2105/ajph.2013.301553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlemass, Keesha . 2019. “Hungry and Marginalized: The Intersection of Mental Health and Food Insecurity in the Returning Prison Population.” November 13. National Conference of Black Political Scientists (NCOBPS) Annual Meeting. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3283494

- National Commission on Hunger . 2015. “Freedom from Hunger: An Achievable Goal for the United States of America.” [Online]. https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/hungercommission/20151216222324/; https://hungercommission.rti.org/Portals/0/SiteHtml/Activities/FinalReport/Hunger_Commission_Final_Report.pdf

- Nestle, Marion . 2019. “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): History, Politics, and Public Health Implications.” American Journal of Public Health 109: 1631–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network for Public Health Law (NPHL) . 2020. “Food Security Issue Brief: Effect of the Denial of SNAP Benefits on Convicted Drug Felons.” April. https://www.networkforphl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Issue-Brief-Snap-Felon-Ban-Updated.pdf

- Nord, Mark , Coleman‐Jensen Alisha, and Gregory Christian. 2014. “Prevalence of U.S. Food Insecurity Is Related to Changes in Unemployment, Inflation, and the Price of Food.” ERR‐167, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Owen, Barbara , Wells James, and Pollock Jocelyn. 2017. In Search of Safety: Confronting Inequality in Women's Imprisonment. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pager, Devah . 2003. “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology 108 (5): 937–75. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Mattie . 2019. “Criminal Justice Reform Paves the Way for Welfare Reform.” Governing (January 22). https://www.governing.com/topics/health-human-services/gov-welfare-felons-states-federal-ban-tanf-snap-pennsylvania.html

- Rosenbaum, Dottie , Bolen Ed, Neuberger Zoe, and Dean Stacy. 2020. “USDA, States Must Act Swiftly to Deliver Assistance Allowed by Families First Act.” Center for Budget and Policy Priorities April 07. [Online]. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/usda-states-must-act-swiftly-to-deliver-food-assistance-allowed-by-families

- Rosenbaum, Dottie , Dean Stacy, and Neuberger Zoe. 2020. “The Case for Boosting SNAP Benefits in Next Major Economic Response Package.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- Rosenberg, Alana , Groves A. K., and Blankenship K. M.. 2017. “Comparing Black and White Drug Offenders: Implications for Racial Disparities in Criminal Justice and Reentry Policy and Programming.” Journal of Drug Issues 47 (1): 132–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santo, Alysia , and Iaboni Lisa. 2015. “What's in a Prison Meal?” The Marshall Project (July 07). [Online]. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/07/07/what-s-in-a-prison-meal

- Schanzenback, Diane , and Tomeh Natalie. 2020. “State Levels of Food Insecurity During the COVID‐19 Crisis.” Institute for Policy Research Rapid Research Report (July 14). [Online]. https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-rapid-research-reports-app-visualizes-food-insecurity-14-july-2020.pdf

- Sugie N. F. (2012). Punishment and Welfare: Paternal Incarceration and Families' Receipt of Public Assistance. Social Forces, 90, (4), 1403–1427. 10.1093/sf/sos055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swavola, Elizabeth , Riley Kristine, and Subramanian Ram. 2016. Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform. New York: Vera Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Tai Don Bambino Geno, Shah Aditya, Doubeni Chyke A, Sia Irene G, Wieland Mark L (2020). The Disproportionate Impact of COVID‐19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 10.1093/cid/ciaa815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa, Alexander , and Jackson Dylan B.. 2019. “Food Insecurity among Formerly Incarcerated Adults.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 46 (10): 1493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, Alexander , and Jackson Dylan B.. 2020. “Incarceration Exposure and Maternal Food Insecurity During Pregnancy: Findings from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2004–2015.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 24 (1): 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Council of State Governments Justice Center . 2020. National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction [Online]. https://niccc.csgjusticecenter.org/

- The New York Times . 2020. Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest Map and Case Count https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html. Accessed September 08, 2020.

- The Sentencing Project . 2020. Trends in U.S. Corrections Factsheet [Online]. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/trends-in-u-s-corrections/

- Tran, Nguyen Toan , Baggio Stéphanie, Dawson Angela, O'Moore Éamonn, Williams Brie, Bedell Precious, Simon Olivier, Scholten Willem, Getaz Laurent, and Wolff Hans. 2018. “Words Matter: a Call for Humanizing and Respectful Language to Describe People Who Experience Incarceration.” BMC International Health and Human Rights 18 (1): 41 10.1186/s12914-018-0180-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney, Kristin . 2015. “Paternal Incarceration and Children's Food Insecurity: A Consideration of Variation and Mechanisms.” Social Service Review 89 (2): 335–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle, Cody . 2019. “Snapping Back: Food Stamp Bans and Criminal Recidivism.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11 (2): 301–27. 10.1257/pol.20170490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Commission on Civil Rights . 2019. “Briefing Report: Collateral Consequences: The Crossroads of Punishment, Redemption and the Effects on Communities.”

- Venters, Homer . 2019. Life and Death in Rikers Island. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vera Institute of Justice . 2020. COVID‐19 and Criminal Justice: City and State Spotlights [Online]. https://www.vera.org/covid-19/criminal-justice-city-and-state-spotlights

- Wang, Emily A. , Zhu Gefei A., Evans Linda, Carroll‐Scott Amy, Desai Rani, and Fiellin Lynn E.. 2013. “A Pilot Study Examining Food Insecurity and HIV Risk Behaviors among Individuals Recently Released from Prison.” AIDS Education and Prevention 25 (2): 112–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western, Bruce . 2018. Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Western, Bruce , Braga Anthony A., Davis Jaclyn, and Sirois Catherine. 2015. “Stress and Hardship after Prison.” American Journal of Sociology 120 (5): 1512–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Mechanic D., Rogut R., Colby D., and Knickman J., eds. 2005. “Patterns and Causes of Disparities in Health” In Policy Challenges in Modern Health Care. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wolkomir, Elizabeth . 2018. How SNAP Can Better Serve the Formerly Incarcerated. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; March 16. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-6-18fa.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wright, James E. , and Merritt Cullen C.. 2020. “Social Equity and COVID‐19: The Case of African Americans.” Public Administration Review 80: 820–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Crystal S. 2017. “Does Public Assistance Reduce Recidivism?” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 107 (5): 551–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Zhen . 2020. Jail Inmates in 2018. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji18.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]