Abstract

Background

Previous studies have demonstrated the possibility of adverse effects of prolonged wearing of personal protective equipment in healthcare workers. However, there are a few studies about the effects on skin characteristics after wearing a mask for non‐healthcare workers. In this study, we evaluated the dermatologic effects of wearing a mask on the skin over time.

Materials and Method

Twenty‐one healthy men and women participated in the study. All participants wore masks for 6 hours consecutively. Three measurements were taken (a) before wearing the mask, (b) after wearing the mask for 1 hour, and (c) after wearing the mask for 6 hours. Skin temperature, skin redness, sebum secretion, skin hydration, trans‐epidermal water loss, and skin elasticity were measured.

Results

The skin temperature, redness, hydration, and sebum secretion were changed significantly after 1 and 6 hours of wearing a mask. Skin temperature, redness, and hydration showed significant differences between the mask‐wearing area and the non–mask‐wearing area.

Conclusion

Mask‐wearing conditions and time can change several skin characteristics. In particular, it is revealed that the perioral area could be most affected.

Keywords: COVID‐19, face mask, perioral area, skin characteristics, skin hydration, skin redness, skin temperature

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was observed since December 2019 that has spread worldwide. Because of the high transmission rate of COVID‐19 1 and propensity for airborne infection, 2 it has become a necessity to wear personal protective equipment (PPE), especially face masks. Wearing a mask is very important to prevent infectious disease transmission, but it may causes adverse effects on the skin. 3 Prolonged mask‐wearing can cause erythema, eruption, pustules, papules, pigmentation, and contact dermatitis along the areas of contact. 4 The adverse effects of prolonged PPE use by healthcare workers have been studied extensively. 5 , 6 Since the widespread and mandatory use of face masks has been implemented globally for all individuals, a recent study demonstrated the effects of face masks in non‐healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 7 The number of people affected by dermatologic conditions, such as increased skin sensitivity, irritation, and itching, has been increasing.

Several studies have demonstrated skin temperature changes or discomfort secondary to mask‐wearing, 2 , 7 but no study has been conducted about the changes in skin characteristics over time from wearing a mask. Other situations in which wearing a mask may continue to exist in the future. Because of the widespread need to wear a mask, it is necessary to study its dermatologic effects. Therefore, in this study, we investigated changes in skin characteristics from wearing the mask over time.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Subject recruitment, and environmental and mask‐wearing conditions

Twenty‐one healthy men and women in their 20s, 30s, and 40s participated in this study. Participants with skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and face mask allergies were excluded from the study. All participants were asked to wear a mask for 6 hours while working indoors. Participants were fully informed about the details and objectives of the study. Participation was voluntarily and a written informed consent was provided by the included subjects.

During the first hour, participants were instructed to wear a mask while staying in a controlled room to minimize environmental influences. The room temperature was controlled to 22 ± 2°C, and the relative humidity (RH) was maintained at 50 ± 5%. For the remaining 5 hours, participants were instructed to wear a mask while working as usual in their workplace. A Korea Filter 94 (KF94) mask was provided to all participants during the 6‐hour experimental period. The KF94 mask is a medical mask certified by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in Korea as having more than 94 percent dust collection rate. Measurement of skin characteristics was obtained (a) before wearing the mask (after washing the face), (b) after wearing the mask for 1 hour, and (c) after wearing the mask for 6 hours. The following skin characteristics were measured: temperature, redness, hydration, sebum level, elasticity, and trans‐epidermal water loss (TEWL). The areas measured for each skin characteristics are shown in Figure 1.

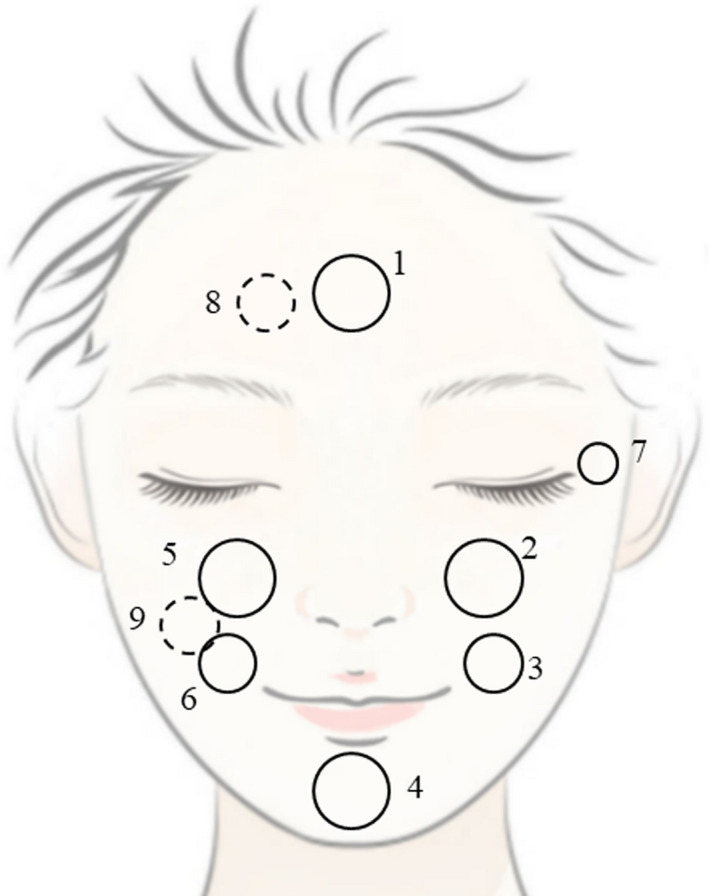

Figure 1.

Image of the measuring areas by skin characteristics. Mask‐wearing area: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9; non–mask‐wearing area: 1, 7, 8; skin temperature and sebum: 1, 2, 3, 4; trans‐epidermal water loss (TEWL): 4, 6; recovery of skin barrier: 8, 9; skin hydration: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7; skin redness: 1, 2; skin elasticity: 2, 7

2.2. Measurement of skin temperature and skin redness

Skin temperature was measured on the forehead, cheeks, perioral area, and chin using a thermal imaging camera (FLIR T640, Wilsonville, USA). Facial images were taken using VISIA‐CR (CANFIELD, Fairfield, USA). Analysis of skin redness was performed on the forehead and cheeks using the RBX red mode image of VISIA‐CR.

2.3. Measurement of skin hydration, sebum, and skin elasticity

Skin hydration, sebum, and skin elasticity were measured using the Corneometer®, Sebumeter®, and Cutometer® MPA580 devices (C + K, Köln, Germany), respectively. Skin hydration measurements were performed on the forehead, periorbita, cheeks, perioral area, and chin. Sebum secretion was measured on the forehead, cheeks, perioral area, and chin. Skin elasticity measurements were conducted on the periorbita and cheeks.

2.4. Measurement of trans‐epidermal water loss

TEWL was measured on the forehead, cheeks, perioral area, and chin using a Vapometer (Delfin Technology Ltd, Kuopio, Finland). We inflicted skin damage on the forehead and cheeks by tape‐stripping (TS) to evaluate the recovery of the skin barrier while wearing a mask. TS was performed until the value reached 1.4‐1.7 times compared with baseline.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM Corp., Chicago, USA). The changes in skin characteristics from mask‐wearing and wearing time were compared by RM‐ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

3. RESULTS

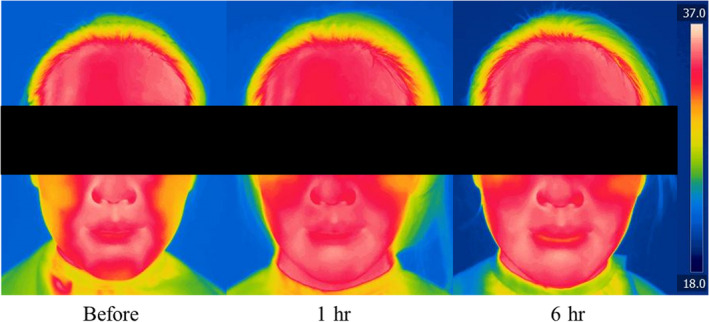

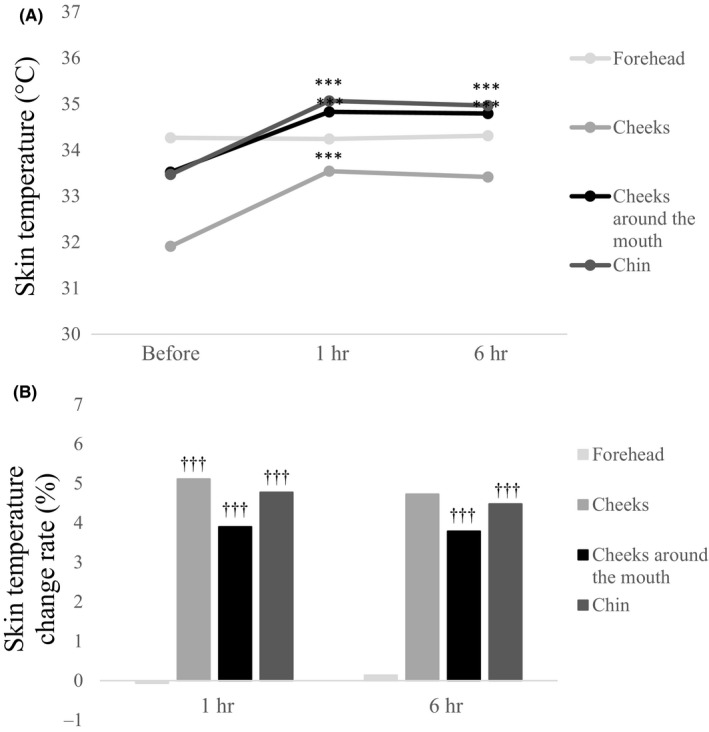

We included 21 healthy participants in this study. The effects of mask‐wearing on skin characteristics were varied. Skin temperature on the cheeks, perioral area, and chin was higher 1 hour after wearing the mask compared with before wearing the mask (cheeks: 1.633 ± 1.229°C; perioral area: 1.310 ± 1.064°C; chin: 1.600 ± 1.235°C). The skin temperature of the perioral area and chin was also higher 6 hours after wearing the mask compared with before mask‐wearing (perioral area: 1.271 ± 1.075°C; chin: 1.500 ± 1.034°C) (Figure 2). However, skin temperature did not increase proportionally to longer mask‐wearing time. There was no significant difference in skin temperature between 1 and 6 hours after mask‐wearing. The temperature remained constant after increasing to a certain level. The skin temperature of the cheeks, perioral area, and chin showed a significant difference than the non–mask‐wearing area of the forehead (Figure 3). The skin temperature of the forehead was similar to the temperature of the mask‐wearing area before and after wearing the mask.

Figure 2.

Image of the skin temperature variations after mask‐wearing over time

Figure 3.

The skin temperature measurements after wearing the KF94 mask. The skin temperature measurement before and after mask‐wearing for each measurement area (A). The rate of change in skin temperature according to the time of wearing the mask compared with before wearing the mask (B). *P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .001 1 or 6 h after wearing a mask vs before wearing a mask. †<.05, †† P < .005, ††† P < .001 non–mask‐wearing area vs mask‐wearing area

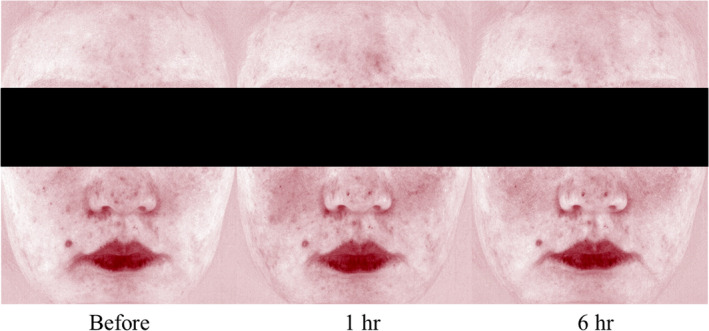

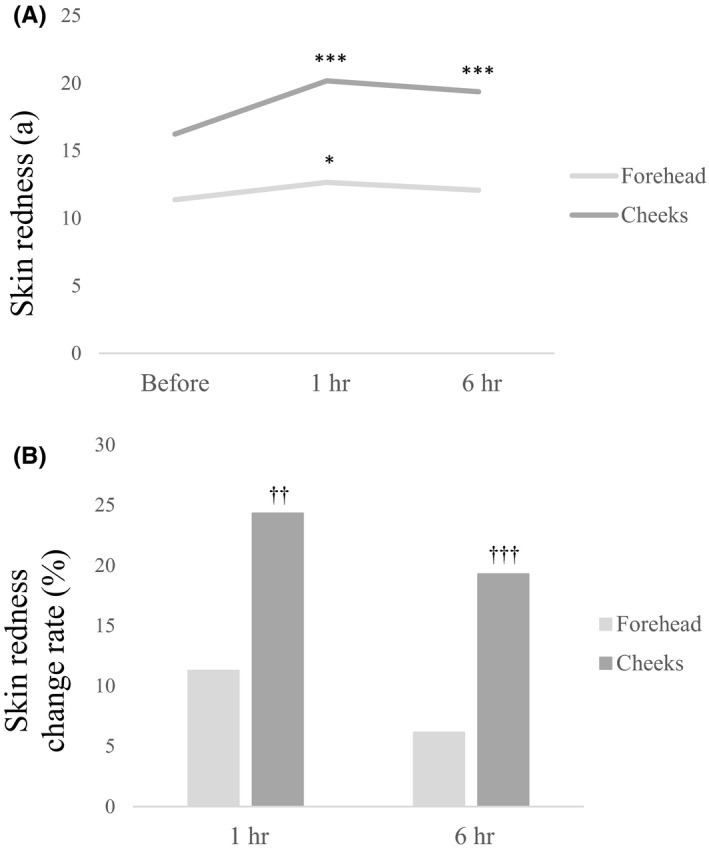

Skin redness of the cheeks was higher at 1 and 6 hours after wearing the mask than that before mask‐wearing. The skin redness of the forehead also increased after 1 hour of wearing the mask (Figure 4). The increase in skin redness of the cheeks was significantly higher than that of the forehead at both time points (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Image of the skin redness variations after mask‐wearing over time

Figure 5.

The skin redness measurement after wearing the KF94 mask. The skin redness measurements before and after wearing the mask for forehead and cheeks (A). The rate of change in skin redness according to the time of wearing the mask compared with before wearing the mask (B)

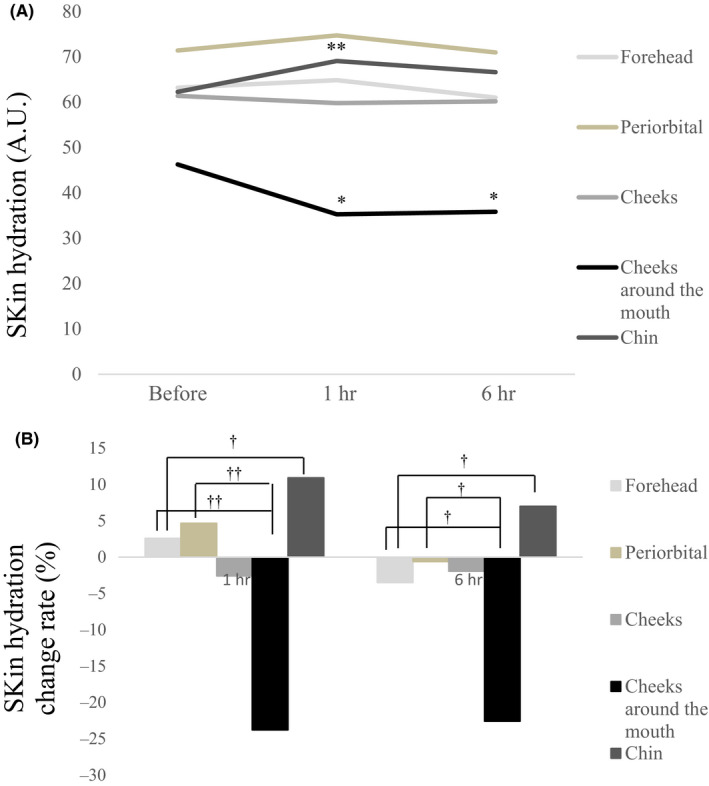

Skin hydration showed various results for each measurement area. Skin hydration of the perioral area was lower after 1 and 6 hours of mask‐wearing compared with before mask‐wearing. It also showed a significant difference compared with the non–mask‐wearing area (forehead and periorbita). Skin hydration of the chin and periorbita was higher 1 hour after wearing the mask compared with before (Figure 6). Measurements of skin hydration of the forehead and cheeks showed no significant changes.

Figure 6.

The skin hydration measurements after wearing the KF94 mask. The skin hydration before and after wearing of the mask for each measurement area (A). The rate of change in skin hydration according to the time of wearing the mask compared with before wearing the mask (B)

Sebum secretion of the forehead, cheeks, chin, and perioral area was higher after 1 and 6 hours of mask‐wearing than before mask‐wearing. There was no significant difference between the mask‐wearing area and non–mask‐wearing area.

The recovery of the skin barrier showed no significant difference between mask‐wearing and non–mask‐wearing areas. The TEWL increased 1.4‐1.7 times after TS on the forehead and cheeks. When compared to immediately after TS, TEWL decreased by about 7.571‐11.627% after 1 hour, and there was no significant difference. Alternatively, TEWL decreased by 22.896‐32.053% after 6 hours, and there was a statistically significant difference compared with immediately after TS. There was no significant difference between the forehead and cheeks at both time points. As a result, there was no difference in the skin recovery ability between the mask‐wearing area and non–mask‐wearing area. After 6 hours, both areas showed similar recovery rates. The TEWL of other areas, the perioral area and chin showed no significant difference. The skin elasticity of the cheeks and periorbita showed no significant difference.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we attempted to verify the dermatologic effects of wearing a mask and skin changes over time. We revealed that skin temperature, redness, and hydration showed dermatologic changes after mask‐wearing.

Because of COVID‐19, wearing a mask has become essential, even for non‐healthcare workers. There are some studies conducted on changes in skin temperature, discomfort, physiological factors, and microclimate of the mask when wearing a mask. 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 However, no studies are about the skin changes caused by mask‐wearing and changes over time. There is a possibility that prolonged mask‐wearing may be the norm even for non‐healthcare workers. Hence, studying skin characteristics during mask‐wearing is important.

Skin temperature, redness, and hydration were changed by face mask‐wearing over time. Skin temperature was higher in the perioral area and chin and after wearing the mask. It increased significantly even after 1 hour of wearing the mask. These results are thought to be due to the increased exposure to one's own hot breath and the simultaneously increasing internal temperature secondary to the sealing effect of the mask. The skin temperature of the cheeks increased after 1 hour of wearing the mask, but not after 6 hours. This is thought to be due to homeostasis to maintain temperature. 12 Although the cheeks are also within the mask‐wearing area, unlike the perioral region, it is not adjacent to the mouth. This may account for the slight difference in results. It may also be influenced by outside air because the mask does not completely seal this area. The forehead and non–mask‐wearing areas showed similar temperatures during the experiment.

Skin redness was measured on the forehead and cheeks, where redness can be readily observed due to more prominent blood vessels. An increase in skin redness was observed on both the forehead and cheeks after 1 hour of wearing the mask. Unlike other characteristics, the effect on blood vessels is difficult to localize, so there is a possibility that the effect on the mask‐wearing area also affected the forehead. After 6 hours of wearing the mask, only the redness of the cheeks increased significantly. The skin temperature and skin redness between the mask‐wearing area and non–mask‐wearing area were slightly different. The forehead was not directly affected by the sealing effect of the mask, so the skin surface (skin temperature) and the deeper layers of the skin (skin redness) may have been affected differently.

The perioral area is the closest measurement site to the mouth, thus, it was the most influenced by the direct effect of breathing. Skin hydration of the perioral area was lower after 1 and 6 hours after wearing the mask. On the other hand, other areas showed varying results for each area.

To compare the recovery capacity of the skin barrier, TS was performed on the forehead and cheeks. After 6 hours, the TEWL of the forehead and cheeks was significantly lower than that immediately after TS, and there was no difference between the two sites. The effect of wearing the mask on the ability of the skin barrier to recover could not be determined. In this experiment, TS was performed until the TEWL value increased by 1.4 times from baseline. However, the forehead and cheek may differ according to the area and individual differences. Therefore, multiple TSs may have produced more accurate results to measure the recovery capacity of the skin barrier than the method used in this study. There was no significant difference in TEWL on the perioral area and chin.

Sebum secretion significantly increased in all areas at all measurement time points. There is a possibility that increased sebum secretion was secondary to the higher temperature and humidity inside the mask. This environment might have an overall effect on the face. However, for a more accurate interpretation, it is necessary to compare our results to skin measurements devoid of a mask to assess natural sebum secretion during daytime, which may show variable results. 13

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we identified that wearing a mask may cause skin changes. Skin temperature and sebum increased on the cheeks, perioral area, and chin. Skin redness of the cheeks also increased. Alternatively, skin hydration of perioral area decreased. In particular, there was a significant difference after mask‐wearing in skin temperature, redness, and hydration compared with the non–mask‐wearing area. The effect of mask‐wearing on skin hydration was more visible on the perioral area. Importantly, we studied the dermatologic effects of wearing a mask on various skin characteristics across a 6‐hour duration. Our results show that skin changes may occur from wearing of a mask, which can occur after a relatively short amount of time. Wearing a mask during the COVID‐19 pandemic is essential, but at the same time preparing for expected skin changes is also important for skin health. In this respect, our findings suggest the skin covered with the face mask need to be treated extra carefully due to certain changes of skin characteristics.

Park S‐R, Han J, Yeon YM, Kang NY, Kim E. Effect of face mask on skin characteristics changes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Skin Res Technol.2021;27:554–559. 10.1111/srt.12983

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaihui HU, Fan J, Li X, et al. The adverse skin reactions of health care workers using personal protective equipment for COVID‐19. Medicine. 2020;99:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scarano A, Inchingolo F, Lorusso F. Facial skin temperature and discomfort when wearing protective face masks: thermal infrared imaging evaluation and hands moving the mask. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atzori L, Ferreli C, Atzori MG, et al. COVID‐19 and impact of personal protective equipment use: from occupational to generalized skin care need. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Das A, Kumar S, Sil A, et al. Skin changes attributed to protective measures against COVID‐19: a compilation. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al Badri FM. Surgical mask contact dermatitis and epidemiology of contact dermatitis in healthcare workers. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;30:183‐188. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foo CCI, Goon ATJ, Leow YH, et al. Adverse skin reactions to personal protective equipment against severe acute respiratory syndrome – a descriptive study in Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:291‐294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Szepietowski JC, Matusiak L, Szepitowska M, et al. Face mask‐induced itch: a self‐questionnaire study of 2,315 responders during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roberge RJ, Kim JH, Benson SM. Absence of consequential changes in physiological, thermal and subjective responses from wearing a surgical mask. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;181:29‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li Y, Tokura H, Guo YP, et al. Effects of wearing N95 and surgical facemasks on heart rate, thermal stress and subjective sensations. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2005;78:501‐509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherrie JW, Wang S, Mueller W, et al. In‐mask temperature and humidity can validate respirator wear‐time and indicate lung health status. J Eposure Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2019;29:578‐583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roberge RJ, Aitor Coca W, Williams J, et al. Physiological impact of the N95 filtering facepiece respirator on healthcare workers. Respir Care. 2010;55:569‐577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grahn D, Heller HC. The physiology of mammalian temperature homeostasis. ITACCS Crit Care Monogr; 2004:1‐21. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Le Fur I, Reinberg A, Lopez S, et al. Analysis of circadian and ultradian rhythms of skin surface properties of face and forearm of healthy women. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:718‐724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]