Abstract

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) is a rapidly evolving pandemic caused by the coronavirus Sars‐CoV‐2. Clinically manifest central nervous system symptoms have been described in COVID‐19 patients and could be the consequence of commonly associated vascular pathology, but the detailed neuropathological sequelae remain largely unknown. A total of six cases, all positive for Sars‐CoV‐2, showed evidence of cerebral petechial hemorrhages and microthrombi at autopsy. Two out of six patients showed an elevated risk for disseminated intravascular coagulopathy according to current criteria and were excluded from further analysis. In the remaining four patients, the hemorrhages were most prominent at the grey and white matter junction of the neocortex, but were also found in the brainstem, deep grey matter structures and cerebellum. Two patients showed vascular intramural inflammatory infiltrates, consistent with Sars‐CoV‐2‐associated endotheliitis, which was associated by elevated levels of the Sars‐CoV‐2 receptor ACE2 in the brain vasculature. Distribution and morphology of patchy brain microbleeds was clearly distinct from hypertension‐related hemorrhage, critical illness‐associated microbleeds and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which was ruled out by immunohistochemistry. Cerebral microhemorrhages in COVID‐19 patients could be a consequence of Sars‐ CoV‐2‐induced endotheliitis and more general vasculopathic changes and may correlate with an increased risk of vascular encephalopathy.

Keywords: COVID19, ACE2, Sars‐CoV‐2, endotheliitis

Clinically manifest central nervous system symptoms are common in COVID‐19 patients but their causes are still unknown. We present here four patients who tested positive for Sars‐CoV‐2 with cerebral haemorrhages which were most prominent at the grey and white matter junction of the neocortex and the brainstem. We present evidence of intracerebral endotheliitis in COVID‐19 patients which could predispose to more general vasculopathic changes and may correlate with an increased risk of vascular encephalopathy.

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19), caused by infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (Sars‐CoV‐2), has become a worldwide pandemic. 1 Symptoms of COVID‐19 vary widely and range from asymptomatic disease to severe pneumonia and multiorgan failure. 2 A severe disease course is more likely in older patients and patients with pre‐existing respiratory and cardiovascular conditions. 2 Patients with severe Sars‐CoV‐2 infection may present with ischaemic stroke 3 , 4 or even fatal intracerebral haemorrhage. 5 To date, little is known about the neuropathological sequelae of COVID‐19. The largest published autopsy series of COVID‐19 neuropathology reported microthrombi and acute haemorrhagic infarction in a significant number of patients 6 , while another more recent study found evidence of lymphocytic encephalitis and meningitis. 7 Endotheliitis of the brain and extraneural organs has been shown in Sars‐CoV‐infected patients. 8 Similarly, it is a recurrent feature in the lungs and other peripheral organs of Sars‐CoV‐2‐infected patients 9 but has not yet been reported in the central nervous system. We speculated that cerebrovascular pathology in COVID‐19 patients could be a direct consequence of hitherto unidentified cerebral endotheliitis caused by Sars‐CoV‐2.

We retrospectively analysed all brain autopsies from Sars‐CoV‐2‐infected patients referred to our department, for the presence of vasculopathic changes and cerebral haemorrhage (Table 1). We excluded two patients with overt disseminated intravascular coagulopathy 10 (DIC, one patient was described previously 11 ). Accordingly, we present a detailed neuropathological work‐up of four Sars‐CoV‐2‐infected patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 70 | 77 | 79 | 81 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Male |

| Pre‐existing disease; Cardiovascular risk factors | Hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, kidney transplantation 2013 | Hypertension, depression | Obesity, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, severe pulmonary hypertension, chronic renal failure, M. Waldenström | Hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency |

| Pre‐existing disease; medication | ASA, Tacrolimus, Mycophenolat, Bisoprolol, Amlodipin | Lithium sulfate, Bisoprolol | Verapamil, Tadalafil, Macitentan, Apixaban, Toresamid, Eplerenon | ASA, Losartan, Metolprolol, Ranolazin, Ezetimib. Rosuvastin |

| Clinical course | ||||

| Empirical COVID−19 treatment | Hydroxychloroquine | None | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine, Remdesivir |

| Pre‐intubation/worst SPO2 | 89% | No intubation/53% measured 2 days before death | No intubation/70% | 89% |

| Anticoagulation in the last 3 days before CNS disorder | ASA at admission, therapeutic anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin in ICU | Prophylactic Enoxaparine 40 mg/d | Apixaban | Prophylactic dosage with unfractionated heparin |

| CNS disorder | Confusion at admission, asymmetric reactive pupils, negative wake‐up | No CNS disorder | No CNS disorder | Negative wake‐up |

| Concomitant condition a |

Invasive mechanical ventilation, prone positioning CRRT, mesenteric ischaemia, myocardial injury |

O2‐Therapy via high flow mask/nasal cannula | O2‐Therapy | Invasive mechanical ventilation, pneumothorax |

| Relevant pathological laboratory values at time of CNS disorder | CRP 299 mg/L, lymphocyte count 0,29 G/L, IL‐63919 ng/L, fibrinogen 6,7 g/L, d‐dimer 2.42 mg/L, thrombocyte count 177 G/L | CRP 145 mg/L, lymphocyte count 0.78 G/L, thrombocyte count 427 G/L, fibrinogen 8.79 g/L | CRP 246 mg/L, lymphocyte count 0.52 G/L, IL‐6 NA, fibrinogen NA, d‐dimer NA, thrombocyte count 238 GLl | CRP 227 mg/L, lymphocyte count 0,82 G/L, IL‐6175 ng/L, fibrinogen 5,9 g/L, d‐dimer 11,1 mg/L |

| DIC score b | 3 | NA | NA | 3 |

| Time from disease onset to manifestations of CNS disorder, days | 2 | No CNS disorder | No CNS disorder | 14 |

| Neuroimaging |

CT Scan: unremarkable Post‐mortem brain MRI/SWI‐sequence: Multiple microbleeds/haemorrhages |

NA | NA | NA |

| Outcome at ICU discharge | Died from multi‐organ failure and mesenterial ischaemia | Died under palliative care | Died from hypoxaemia and severe pulmonary hypertension under palliative care | Died from cardio‐pulmonary failure under palliative care |

| Pathological findings | ||||

| Brain weight, g | 1374 | 1239 | 1364 | 1626 |

| Gross pathology | Diffuse oedema; punctuate haemorrhage (frontal and parietal cortex, basal ganglia, pons, corpus callosum) | unremarkable | unremarkable |

Mild, patchy atherosclerosis; mild diffuse atrophy; punctuate haemorrhage (corpus callosum, hypothalamus, frontal and temporal cortex) |

| Haemorrhages | ||||

| Neocortex | + | + | + | + c |

| Hippocampus | − | + | − | − |

| Basal ganglia | − | + | + | − |

| Thalamus/Hypothalamus | − | + | + | + |

| Stria olfactoria | + | + | − | − |

| Mesencephalon | + | + | + | − |

| Pons | + | + | + | − |

| Medulla oblongata | + | + | − | − |

| Cerebellum | − | + | − | − |

| Other microscopic findings | Endotheliitis, diffuse intravascular thrombosis, perivasal lymphocytic infiltrates, hypertensive microangiopathic changes, calcifications dentate gyrus | Intravascular microthrombi, hypertensive microangiopathic changes | Endotheliitis, a neuron with granulovacuolar degeneration in the hippocampus, hypertensive microangiopathic changes |

Brainstem‐predominant alpha synucleinopathy, hypertensive microangiopathic changes, subacute ischaemia frontal cortex |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (Congo red/beta amyloid) | − | − | − | − |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CNS, central nervous system; CRP, C‐reactive protein; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; CT, computed tomography; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, ICU, intensive care unit; IL‐6, Interleukine 6; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available, SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation; SWI, Susceptibility weighted imaging.

Concomitant condition: additional findings which occurred at the time of the neurological deficits.

DIC score according to International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.11

This patient harboured fresh juxtacortical haemorrhages and multiple subacute haemorrhages in the corpus callosum.

Detailed clinical information is provided in Table 1 and Data S1. Four patients (three males, one female, age range 70–81 years) presented with progressive respiratory symptoms, three were diagnosed with bilateral COVID‐19 pneumonia during hospitalisation. Patient 2 also presented with bilateral pneumonia, consistent with COVID‐19, and the lung specimen taken at autopsy tested positive for Sars‐CoV‐2, although two previous nasopharyngeal swabs were negative. None of the patients showed laboratory signs of overt DIC (Table 1). 10 Ante‐mortem cranial tomography studies performed in patient 1 were unremarkable. All patients died 5–15 days after admission.

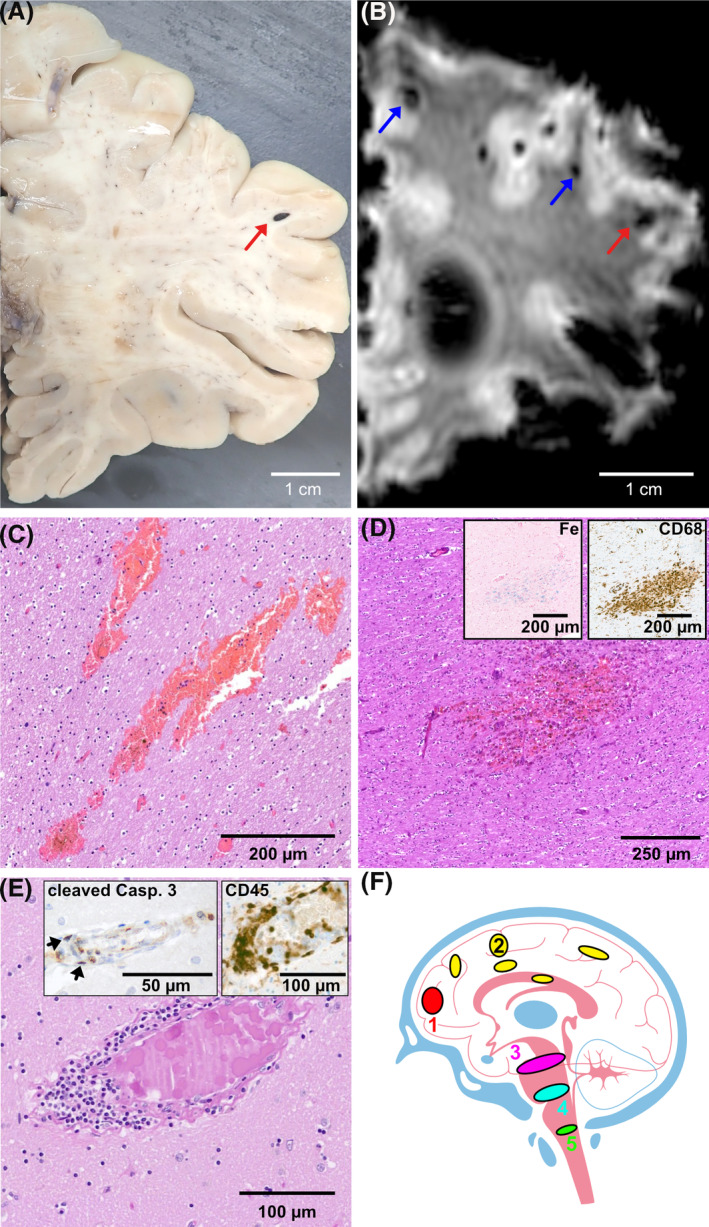

Endotheliitis in the lungs of patient 1 9 and inflammatory olfactory neuropathy in patients 1 and 3 have been described earlier. 12 Gross examination of the brains was unremarkable except in two cases (patients 1 and 4), which revealed diffuse petechial haemorrhage, most prominent at the grey‐white matter junction of the neocortex (Figure 1A, Table 1). Corresponding post‐mortem magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of one brain showed multiple cerebral petechial haemorrhages on susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) (patient 1, Figure 1B). On histology, the vast majority of the haemorrhages were fresh (Figure 1C), without evidence of haemoglobin breakdown products on Prussian blue stains. Juxtacortical microbleeds were observed in all patients, most conspicuous in the frontal lobe. Additionally, petechial haemorrhages were observed in the thalamus, mesencephalon and pons (Table 1). In one case, multiple intraparenchymal subacute haemorrhages were found in the corpus callosum (patient 4, Figure 1D). Fresh haemorrhages were both perivascular, as well as intraparenchymal without relation to vasculature. In all cases, there was evidence of diffuse intravascular thrombosis. In small veins of the basal ganglia of two patients (1 and 3), intra‐endothelial lymphocytic and monocytic inflammation with occasional apoptotic figures were observed, consistent with the previously reported “endotheliitis” in Sars‐CoV‐2‐infected patients 9 (patients 1 and 3, Figure 1E). Immunohistochemistry for ACE2 consistently revealed detectable expression in all but one patient diagnosed with COVID‐19 (Figure S1). Additional staining of three pre‐pandemic autopsy controls revealed very faint or absent ACE2 expression (Figure S1 and Data S1). To test whether the younger age of the controls confounded ACE2 expression, we compared ACE2 transcripts from basal ganglia from the Genotype‐Tissue Expression project (GTEx, total of n = 205 patients). We did not see increased gene expression during ageing (Data S1). Additional lymphocytic “cuffing” was observable in two cases (patients 1 and 3). Congo red stains and immunohistochemistry for beta‐amyloid were negative in all cases.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Gross examination was significant for multiple, mostly juxtacortical haemorrhages (patient 1). (B) Post‐mortem susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) of brain revealed multiple microbleeds/haemorrhages (patient 1). (C) H&E‐stained section showing fresh haemorrhages in the centrum semiovale (patient 2). (D) Subacute haemorrhage containing macrophages (CD68, right insert) and blood breakdown products (Prussian blue, Fe, left insert) in the corpus callosum of patient 4. (E) Diffuse intravascular microthrombosis and endotheliitis in the basal ganglia of patient 1. Elevated apoptosis, as demonstrated by cleaved caspase 3 immunohistochemistry, was observable in endothelial cells and intramural infiltrates but not in the adjacent parenchyma (cleaved casp. 3, left insert). Intra‐endothelial lymphocytes stained positive on CD45 immunohistochemistry (CD45, right insert). (F) Schematic localisation of the intracerebral haemorrhages: (1) frontal cortex (2) other isocortical areas, as well as deep grey matter (3) mesencephalon (4) pons (5) medulla oblongata

Cerebral petechial haemorrhages may represent a histological correlate of the neurological symptoms observed in the COVID‐19 patients described in this case series. Endothelial cell infection is a recurrent feature in the lungs and other peripheral organs of COVID‐19 patients 9 but has not yet been reported in the brain. 6 , 7 We report here for the first time the presence of intracerebral endotheliitis in two patients diagnosed with Sars‐CoV‐2 infection. The observed endotheliitis could be an autoimmune, late‐onset phenomenon or a direct effect of endothelial infection as angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the Sars‐CoV‐2 receptor, is expressed in the brain vasculature (Figure S1 and Ref. 13). Here, we found higher ACE2 expression in the brain vasculature of patients with endotheliitis than in COVID‐19 patients without endotheliitis or than in control patients (Figure S1). Although control patients were younger on average, comparison of publicly available gene expression data did not show increased ACE2 expression in the basal ganglia during ageing (Data S1). The small number of patients analysed, however, precludes a causal inference.

Recently, the concept of critical illness‐associated microbleeds (CRAM) was introduced. 14 The topology of the microbleeds described in this condition is somewhat similar, but not identical, to the patients in our cohort as well as in hypoxaemic patients after high‐altitude exposure. 14 Correspondingly, hypoxia was the cause of death in all patients from the present case series. The nosological distinction between microbleeds in critically ill patients and COVID‐19 patients is not entirely clear. CRAM show some predilection for the corpus callosum, while in our case series, this pattern was only observed in one patient. Similarly, three out of four patients in our series showed a marked involvement of the brainstem, in contrast to four out of 25 patients described by Fanou et al. 14 Still, haemorrhages might have been aggravated by concomitant acute respiratory distress syndrome.

All patients suffered from arterial hypertension and hypertensive microangiopathy, however, hypertensive microbleeds favour the deep grey matter and the infratentorial region. 15 Elevated risk for thrombosis and pulmonary embolism is well‐documented in COVID‐19 patients, and all the patients received prophylactic anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet therapy, which may have predisposed them to haemorrhagic events. Hydroxychloroquine, which was administered to three patients, has also been reported to cause bleeding. 16 On autopsy, no haemorrhage was seen at predilection sites such as the gastrointestinal tract, thus making solely drug‐induced haemorrhage unlikely. 16

In both patients suffering from prolonged coma and negative wake‐up attempts, intraparenchymal haemorrhages had already been observed grossly suggesting a positive correlation between the severity of the vasculopathy and acute sleep‐wake dysregulation. Accordingly, the distribution of microbleeds showed a neuroanatomical preference for central modulators of wakefulness (pons, mesencephalon and paramedian thalamus, Figure 1E). A similar distribution of brainstem lesions leading to disturbed sleep‐wake regulation can be observed in neurodegenerative diseases, traumatic brain injury and acute vascular events. 17 A major drawback of our study is the plethora of co‐morbidities, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, hypertension and prophylactic anticoagulation, all of which increase the risk of intracerebral haemorrhage. It seems likely that we investigated an at‐risk cohort, which may explain the unusually high occurrence of intracerebral bleeding in our case series compared to another recently published study. 18 Although it is tempting to deduce a causal connection between intracerebral haemorrhage, Sars‐CoV‐2‐induced endothelial inflammation and hypoxaemic damage, the retrospective nature of this study and the small number of patients allows for limited conclusions and necessitates further studies.

Neurological symptoms associated with COVID‐19 have been described with manifold aetiologies, such as ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic encephalopathy and others. 19 In contrast to a recently published case report, we did not observe signs of perivascular demyelination. 20 Cerebral microbleeds have been associated with increased risk for cardiovascular mortality 21 and cognitive deterioration. 22 Additionally, emerging evidence suggests rapidly waning humoral anti‐Sars‐CoV‐2 immunity might be associated with a risk of recurrent infection and subsequent cognitive dysfunction. 23 The temporal evolution of COVID‐19‐associated cerebrovascular pathology remains unclear. Future studies could clarify whether endothelial inflammation is self‐limiting or if similar pathological changes can be observed in COVID‐19 patients without neurological symptoms.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Informed consent for autopsy and publication was given by next‐of‐kin in all cases. Case series do not need institutional review board approval according to Swiss legislation.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/nan.12677.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Data S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express their grateful thanks to the patients’ families without whose contribution this case series would not have been possible. The authors would like to thank Daniela Meir and Fabian Baron for excellent technical assistance.

Peter Steiger, Adriano Aguzzi and Karl Frontzek have equal contributions.

Contributor Information

Peter Steiger, Email: peter.steiger@usz.ch.

Adriano Aguzzi, Email: adriano.aguzzi@usz.ch.

Karl Frontzek, Email: karl.frontzek@usz.ch.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

ACE2 stained slides and the detailed analysis pipeline for ACE2 gene expression comparison across age groups in R3.6.3 are made publicly available via Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13089383. All other pathological slides described in this manuscript are publicly available via Synapse (synapse ID: syn23532584). Pathological slides can be analysed with common open‐source software such as QuPath https://qupath.github.io.

REFERENCES

- 1. The L. COVID‐19: too little, too late? Lancet. 2020;395(10226):755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2268–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large‐vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid‐19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID‐19‐associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 2020;296:E119–E120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bryce C, Grimes Z, Pujadas E, et al. Pathophysiology of SARS‐CoV‐2: targeting of endothelial cells renders a complex disease with thrombotic microangiopathy and aberrant immune response. The Mount Sinai COVID‐19 autopsy experience. medRxiv. 2020. 2020.05.18.20099960 [Google Scholar]

- 7. von Weyhern CH, Kaufmann I, Neff F, Kremer M. Early evidence of pronounced brain involvement in fatal COVID‐19 outcomes. Lancet. 2020;395:E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202:415‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID‐19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor FB Jr, Kinasewitz GT. The diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Curr Hematol Rep. 2002;1(1):34‐40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keller E, Brandi G, Winklhofer S, et al. Large and small cerebral vessel involvement in severe COVID‐19. Stroke. 2020;51:3719–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kirschenbaum D, Imbach L, Ulrich S, et al. Inflammatory olfactory neuropathy in two patients with Covid‐19. Lancet. 2020;396(10245):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631‐637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fanou EM, Coutinho JM, Shannon P, et al. Critical illness‐associated cerebral microbleeds. Stroke. 2017;48(4):1085‐1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee SH, Park JM, Kwon SJ, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with cerebral microbleeds in hypertensive patients. Neurology. 2004;63(1):16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang S, Liu X, Cai L, Zhang J, Zhou C. Longitudinal melanonychia and subungual hemorrhage in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with hydroxychloroquine. Lupus. 2019;28(1):129‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Imbach LL, Valko PO, Li T, et al. Increased sleep need and daytime sleepiness 6 months after traumatic brain injury: a prospective controlled clinical trial. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 3):726‐735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matschke J, Lütgehetmann M, Hagel C, et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID‐19 in Germany: a post‐mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 19(11):919–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID‐19 in 153 patients: a UK‐wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020.7(10):875–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reichard RR, Kashani KB, Boire NA, Constantopoulos E, Guo Y, Lucchinetti CF. Neuropathology of COVID‐19: a spectrum of vascular and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)‐like pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benedictus MR, Prins ND, Goos JD, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM. Microbleeds, mortality, and stroke in Alzheimer disease: the MISTRAL Study. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(5):539‐545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Akoudad S, Wolters FJ, Viswanathan A, et al. Association of cerebral microbleeds with cognitive decline and dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(8):934‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emmenegger M, De Cecco E, Lamparter D, et al. Early plateau of SARS‐CoV‐2 seroprevalence identified by tripartite immunoassay in a large population. medRxiv. 2020;2020.05.31.20118554. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Data S1

Data Availability Statement

ACE2 stained slides and the detailed analysis pipeline for ACE2 gene expression comparison across age groups in R3.6.3 are made publicly available via Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13089383. All other pathological slides described in this manuscript are publicly available via Synapse (synapse ID: syn23532584). Pathological slides can be analysed with common open‐source software such as QuPath https://qupath.github.io.