COVID‐19 has caused the collapse of medical systems in metropolitan areas around the world. Medical personnel are at high risk of mental health problems. 1 Furthermore, they are also susceptible to deterioration of human relations and income reduction due to fear of contagion and stigma. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Some have been encouraged by their families to quit their jobs, some have been avoided by others due to their medical occupations, and some have been prevented from working in multiple facilities, thus leading to financial burdens. Such situations have negatively influenced the motivation of some personnel towards their work. For a stable medical system, the mental health and motivation of medical personnel are critical. Mental illness and voluntary absenteeism could lead to a collapse of medical systems. To date, there has been no tool to comprehensively assess the mental and social factors that potentially impact the mental health and motivation of medical personnel during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The purpose of this study was to develop a new scale, termed the Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP), which can concisely evaluate pandemic‐related mental health and social factors.

To this end, we used the data from a questionnaire to survey the mental health of medical personnel at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital after the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Participant characteristics of 260 medical personnel are provided in Table S1. The details of ethics, study cohort, and statistical analysis are described in Appendix S1.

We conducted a factor analysis of nine question items related to the COVID‐19 pandemic (Table S2). This revealed two factors, namely, concerns about infection (five items) and social stress (four items). Cronbach's α, factor loadings (pattern matrix), and unique variances for each item are shown in Table S3. The original nine‐item scale was named the TMDP (Table S2). The Japanese version is provided in Table S4.

Next, we conducted convergent validity analysis of the TMDP versus the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ‐9), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 Scale (GAD‐7), and the Perceived Stress Scale – 10 (PSS‐10). The TMDP demonstrated convergent validity with the PHQ‐9 (γ = 0.42, P < 0.0001), GAD‐7 (γ = 0.50, P < 0.0001), and PSS‐10 (γ = 0.44, P < 0.0001). Furthermore, Factor 1 and Factor 2 were also correlated with the PHQ‐9, GAD‐7, and PSS‐10 (Table S5).

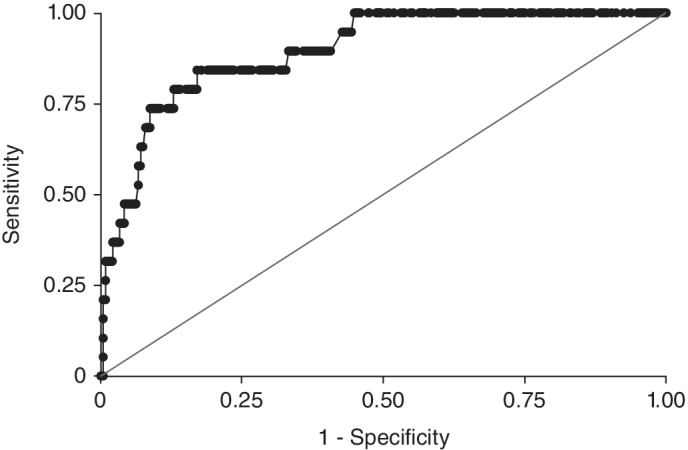

One of the purposes of developing the TMDP was the simultaneous and concise detection of the depressive state or anxiety. Thus, we first analyzed whether the TMDP could detect the depressive state or anxiety. We defined the depressive state and anxiety as PHQ‐9 ≥ 10 and GAD‐7 ≥ 10, respectively. Among the 260 participants, eight individuals had PHQ‐9 scores of 10 or higher. The TMDP's area under the receiver–operator curve (AUC) for depressive state was 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80–0.98; Figure S1A). Among the 260 participants, 17 individuals had GAD‐7 scores of 10 or higher. The TMDP's AUC for anxiety was 0.89 (95%CI, 0.79–0.95; Figure S1B). These results suggested that the TMDP can detect both depressive state and anxiety with high accuracy. Nineteen individuals had PHQ‐9 scores and GAD‐7 scores of 10 or higher. In fact, six of the subjects had PHQ‐9 and GAD‐7 scores above 10. The TMDP's AUC for either depressive state or anxiety was 0.90 (95%CI, 0.80–0.94; Fig. 1). The sensitivities and specificities for each of the cut‐offs are described in Tables S6–S8. A recommended cut‐off score is 14.

Fig. 1.

Receiver–operator curve (ROC) showing accuracy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) for either depressive state or anxiety (N = 260). Area under ROC = 0.90.

In addition to detecting depressive state and anxiety, the TMDP features other advantages, such as inclusion of the social stress factor. Aside from depressive state and anxiety, this is related to motivation, and it cannot be detected by the PHQ‐9 or GAD‐7. It should be noted that in a psychotherapeutic intervention screening with the TMDP, detection of these problems before interviews was helpful. It is reportedly important for medical personnel to feel that hospital organizations and public administrations protect them from infections, social stigma, and financial burden, which would represent effective factors to increase their motivation and reduce their hesitation to work. 7 Therefore, comprehensively understanding the situation of medical personnel with the TMDP and intervening at an early stage will lead to prevention of turnover and absenteeism due to decreased motivation.

In conclusion, we developed a novel scale for assessing the mental health and social stress of medical personnel during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Further long‐term analysis will be necessary to show the usefulness of the TMDP for early intervention to maintain the mental health and prevention of turnover and absenteeism of medical personnel.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1. (A) Receiver–operator curve (ROC) showing accuracy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) for depressive state as defined by the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ‐9) ≥ 10 (N = 260). Area under ROC = 0.90. (B) ROC showing accuracy of TMDP for anxiety as defined by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 Scale (GAD‐7) ≥ 10 (N = 260). Area under ROC = 0.89.

Table S1. Characteristics of respondents.

Table S2. Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP).

Table S3. Factor loadings (pattern matrix) and unique variances.

Table S4. Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP): Japanese version.

Table S5. Pearson correlation coefficients of the Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) with Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ‐9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 Scale (GAD‐7), and Perceived Stress Scale – 10 (PSS‐10).

Table S6. Operating characteristics of Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) against depression at different cut‐offs.

Table S7. Operating characteristics of Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) against anxiety at different cut‐offs.

Table S8. Operating characteristics of Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) against either depression or anxiety at different cut‐offs.

Appendix S1: Supporting information.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (16H06572). We would like to thank those who took part in this study. We would also like to thank the staff members for collaborating for mental health care during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

References

- 1. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020; 3: e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004; 185: 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McMahon SA, Ho LS, Brown H, Miller L, Ansumana R, Kennedy CE. Healthcare providers on the frontlines: A qualitative investigation of the social and emotional impact of delivering health services during Sierra Leone's Ebola epidemic. Health Policy Plan. 2016; 31: 1232–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: 228–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shiao JSC, Koh D, Lo LH, Lim MK, Guo YL. Factors predicting nurses’ consideration of leaving their job during the SARS outbreak. Nurs. Ethics 2007; 14: 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valdez C, Nichols T. Motivating healthcare workers to work during a crisis: A literature review. J. Manag. Policy Pract. 2013; 14: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Imai H, Matsuishi K, Ito A et al. Factors associated with motivation and hesitation to work among health professionals during a public crisis: A cross sectional study of hospital workers in Japan during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. (A) Receiver–operator curve (ROC) showing accuracy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) for depressive state as defined by the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ‐9) ≥ 10 (N = 260). Area under ROC = 0.90. (B) ROC showing accuracy of TMDP for anxiety as defined by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 Scale (GAD‐7) ≥ 10 (N = 260). Area under ROC = 0.89.

Table S1. Characteristics of respondents.

Table S2. Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP).

Table S3. Factor loadings (pattern matrix) and unique variances.

Table S4. Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP): Japanese version.

Table S5. Pearson correlation coefficients of the Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) with Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ‐9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 Scale (GAD‐7), and Perceived Stress Scale – 10 (PSS‐10).

Table S6. Operating characteristics of Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) against depression at different cut‐offs.

Table S7. Operating characteristics of Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) against anxiety at different cut‐offs.

Table S8. Operating characteristics of Tokyo Metropolitan Distress Scale for Pandemic (TMDP) against either depression or anxiety at different cut‐offs.

Appendix S1: Supporting information.