Abstract

We conducted an online consumer survey in May 2020 in two major metropolitan areas in the United States to investigate food shopping behaviors and consumption during the pandemic lockdown caused by COVID‐19. The results of this study parallel many of the headlines in the popular press at the time. We found that about three‐quarters of respondents were simply buying the food they could get due to out of stock situations and about half the participants bought more food than usual. As a result of foodservice closures, consumers indicated purchasing more groceries than normal. Consumers attempted to avoid shopping in stores, relying heavily on grocery delivery and pick‐up services during the beginning of the pandemic when no clear rules were in place. Results show a 255% increase in the number of households that use grocery pickup as a shopping method and a 158% increase in households that utilize grocery delivery services. The spike in pickup and delivery program participation can be explained by consumers fearing COVID‐19 and feeling unsafe. Food consumption patterns for major food groups seemed to stay the same for the majority of participants, but a large share indicated that they had been snacking more since the beginning of the pandemic which was offset by a sharp decline in fast food consumption.

Keywords: coronavirus, delivery, food consumption, grocery shopping, pandemic, pick‐up

1. INTRODUCTION

Consumer food shopping behaviors have undergone significant changes since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) in early 2020. The imminent threat of COVID‐19 that overwhelmed cities and neighborhoods encouraged panicked shopping behaviors that resulted in stock‐outs and purchasing limits on many food items (Schneeweiss & Murtaugh, 2020). These behaviors exposed a deep‐seated lack of confidence and distrust in our global food supply chain. Some speculate that once we emerge from the aftermath of COVID‐19, behaviors will return to normal, while others suggest that behaviors will stick and set a new trajectory for the future of the food industry. The purpose of this study is to highlight consumer food shopping and consumption patterns that were catalyzed by COVID‐19. In addition, we aim to summarize evidence regarding whether consumer‐shopping behaviors will return to pre‐COVID‐19 “norms.”

While much of the emerging research examines retail sectors for durable goods, few empirical studies have focused on changes in food purchases and consumption patterns during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We aim to close this gap in the literature. The significance of the coronavirus pandemic is that it highlights fundamental aspects of consumers' spending behavior in the face of uncertainty and risk. Yet, unlike other extreme events such as natural disasters, which seem similar on many levels, three parameters uniquely define the COVID‐19 pandemic—its reach, duration, and degree of ambiguity about the epidemiology of the virus itself. Therefore, developing a deeper understanding of consumers' food shopping and consumption patterns may provide key insights useful for food retailers and food manufacturers who must quickly adapt to a constantly changing environment. In addition, it is of interest to understand how consumption patterns might have changed during the crisis, for example, whether consumers shift towards (healthier) fresh and unprocessed foods or towards (unhealthier) processed foods. Moreover, we examine if these decisions may be influenced by other factors, such as changes in shopping routines.

In the days immediately preceding shelter‐in‐place and social distancing orders that kept consumers from shopping and dining out, consumer expenditures on certain household items increased significantly compared to the early months of 2020 (January–February). The anxiety induced by the pandemic perpetuated stockpiling behaviors (Hobbs, 2020). Analysis by DecaData shows that the panic‐buying behaviors of consumers began on March 10, as purchases of hand sanitizer, household cleaners, facial tissue, and toilet paper increased to nearly 30 times the rate from earlier weeks. Purchases of these items leveled off by the end of March. However, this may have been attributed to inventory stock‐outs rather than settled behaviors (DecaData, 2020). Furthermore, stock‐outs could effectively perpetuate negative consumer attitudes and contribute to greater levels of uncertainty, as shoppers arrived at the store only to find aisles of empty shelves, and were left without information about when essential items would become available again. These observations are not unlike those established in the literature that evaluates consumer‐purchasing behavior surrounding natural disasters like hurricanes, earthquakes, and floods (Dovarganes, 2005). Empirical studies have shown that a perceived lack of control contributes to predictable shopping patterns, such as compulsive buying or purchasing that is “repetitive and seemingly purposeful” (American Psychiatric Association, 1985, p. 234; Sneath et al., 2009). Victims of disaster engage in compulsive buying not as a rational response, but rather from a place of emotional distress to alleviate a deeply rooted sense of anxiety. The outbreak of COVID‐19 presented a perfect storm that ignited predictably irrational responses at supermarkets, mass merchandisers, and even dollar stores. Much of the information coming from the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), as well as federal, state, and local governments, was dubious. The rates of spread and risk of the contagion were incomplete as virus testing during the early stages of the outbreak was sparsely available. Finally, the unpredictability of the economy, including job insecurity and reduced income, all contributed to emotions rooted in a lack of control that likely fueled observed consumer‐purchasing behaviors (Furman, 2020).

By mid‐May, which marked the 2‐month milestone for most shelter‐in‐place orders, additional data on consumer trends showed that COVID‐19 both magnified and accelerated existing trends, while at the same time reversing others. The trend that was perhaps most apparent at the onset of the outbreak was consumers' channel shifting, which demonstrated consumers' willingness to switch between food retail formats. For years now, we have seen the proportion of consumers' food‐at‐home (FAH) budget spent at grocery stores diminish as expenditure shares at mass merchandisers and other nontraditional formats increase (Chenarides & Jaenicke, 2017; Ver Ploeg et al., 2015). The motivations during COVID‐19 that resulted in agnosticism between formats was likely driven by a variety of factors, such as inventory shortages. In this study, we provide further context surrounding places where consumers acquired food.

Another widely observed pattern throughout the stay‐at‐home period was the shift away from brick‐and‐mortar to online pick‐up and delivery (Offner, 2020; The Food Institute 2020). By the end of March 2020, additional constraints made shopping in‐person unfavorable. Not only was shopping in‐store considered high‐risk, but additional restrictions imposed by retailers themselves or by local mandates made it especially difficult to visit a single store and find it fully stocked. As a result, consumers turned to online services. As the demand for online food purchases surged, fulfillment, and distribution centers were left overwhelmed. Market leaders like Amazon, fulfilled by Whole Foods, were forced to suspend certain services, delivery times were in short supply, and delivery delays were to be expected (Herrman, 2020; Schoolov, 2020). In stark contrast was the demand for goods supplied by local food retailers whose logistics for fulfilling online orders had not been established pre‐COVID‐19. Before the outbreak, Nielsen and the Food Marketing Institute estimated that online grocery sales were expected to constitute 20% of the market by 2025 (Daniels, 2017). This event may have amplified these estimates, and omnichannel could be the incentive‐compatible outcome for both consumers and retailers. We address this in our survey by analyzing participation in online grocery shopping, and the use of both delivery and pick‐up services at grocery stores and other vendors. We also investigate which channels have been used since the outbreak, and begin to develop a consumer profile of those who made use of in‐store and online formats. While not all of those customers might continue using these channels, the results can be used to provide recommendations to food retailers who aim to strengthen their online/pick‐up presence.

The reallocation of food dollars across formats and shopping modes may have been expected. However, one trend that saw a near reversal was category migration. For the last 5–10 years, the “center of the store” aisles had been experiencing a significant drop in sales, while sales for fresh produce, dairy, and other perishable items located around the stores' “perimeter” increased (Gasparro, 2017; LaVito, 2017; Strom, 2012). In response, large food manufacturers began diversifying their product lines by either adding healthier brands or acquiring companies catering to the “Better For You” food trend. Declining sales for center‐aisle products were also concerning for food retailers, as these products come with higher price markups. Therefore, rebranding of the center aisles to make them more appealing to a growing number of health‐conscious consumers was a priority at the retail level (Vellani, 2015). We address this by examining which food groups households consumed more or less compared to their usual pre‐COVID‐19 consumption patterns. Accounting for determinants of this can provide an insight into whether consumers did so voluntarily or because of stock‐outs. This could then point towards potential long‐term trends.

Against this background, this study, which solicited responses from 861 respondents, was designed to examine trends around individuals' shopping habits and changes in consumption patterns during the novel Coronavirus pandemic. It focuses on two metropolitan areas in the United States to elicit key insights about food shopping patterns, purchasing behaviors, and consumption. We carried out this survey during the end of April 2020, after many of the initial tensions subsided, a stimulus package had been introduced, and conversations about reopening the economy were ongoing.

2. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

2.1. Study design

To analyze food consumption patterns during COVID‐19, we designed a survey to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: How have food purchasing behaviors changed?

RQ2: How have food acquisition methods changed?

RQ3: How has food consumption changed?

RQ4: What factors determine changes in food consumption?

To answer these questions, we began by collecting data in Detroit, MI, and Phoenix, AZ, using an online survey. We focused on these two metropolitan areas for the following reasons. First, both areas are similar in that they are two of the most populated metropolitan statistical areas, according to the U.S. Census, yet they are located in very different parts of the country. Second, we chose to interview urban shoppers, as their shopping patterns as well as internet access is crucial for delivery and pick‐up order placement yet very different from those in rural areas (Devadas & Lys, 2011, Hassan, 2015, Lennon et al., 2009, Mahmood et al., 2004, Patel et al., 2015, Sehrawet & Kundu, 2007). With regard to COVID‐19, during the time of the survey, both states in which the study sites are located (Arizona and Michigan) had a similar number of cases. On May 13, when the surveying started, Arizona had 414 new cases, while Michigan had 672. On May 30, when the survey closed, Arizona had 745 new cases, while Michigan had 164. In the meantime, on May 20, MI had 458 new cases, while AZ had 528 (AZDHS, 2020, Michigan, 2020). The survey was programmed by the researchers in the platform Qualtrics. Data were collected by the consumer panel company Dynata between May 13, 2020, and May 30, 2020. The study was approved by the IRB of Arizona State University. Data were analyzed using Stata version 14.

2.2. Survey instrument

In the survey, we asked a series of questions that sought to investigate how individuals' food shopping behaviors and consumption patterns changed during COVID‐19. Shopping behaviors included whether participants bought what they could due to empty shelves, whether they stockpiled food, and how often they went to the food store. We also investigated participation in grocery delivery and pick‐up services before and since COVID‐19. Our main focus, however, was on changes in dietary patterns and food consumption during COVID‐19. To measure dietary changes, we asked “How much has your diet changed since COVID‐19 started?” From a list of responses participants could select any of the following answer categories (multiple options allowed): eat more, eat less, eat about the same, eat less healthy, eat more healthy. To measure changes in food consumption, we asked “How much more or less have you consumed these foods since COVID‐19 started?” for 10 major food groups: fresh produce, dairy, meat, grains, snacks, fast food, frozen food, canned food, prepped food, and bottled water. The answer categories were based on a five‐point Likert scale: A lot more (5), A bit more (4), About the same (3), A little less (2), A lot less (1) and Do not consume. The five responses were recoded, such that “a lot more” and “a bit more” received a value of 3, “about the same” received a value of 2, and “a little less” and “a lot less” received a value of 1. Those who answered “Do not consume” were treated as missing.

2.3. Empirical framework

To answer the first three research questions, we rely on univariate statistical analysis, and the results are reported in Sections 3.1–3.4. To estimate the relationship between individual characteristics and the likelihood that a respondent made changes in their consumption during COVID‐19 (RQ4), we apply an ordered probit model to each food category. As described above, we ask how much respondents made changes to their diet across 10 food categories (fresh produce, dairy, meat, grains, snacks, fast food, frozen food, canned food, prepped food, and bottled water). We use the ordered probit model because it not only takes into account that the responses to our survey instrument are categorical and implicitly rank‐ordered, but that the alternatives are correlated, that is, an alternative (“eat less”) is more similar to one (“eat the same”) than the other (“eat more”). As is the case for other probit models, the ordered probit model assumes a linear functional form for each participant's indirect utility function. The unobserved preference obtained by consumer i to maintain the respective level of consumption during COVID‐19 is:

where is the vector of independent variables including, among others, socio‐demographics, such as age, gender, and education. is a vector of coefficients associated with , and an error term, , which is assumed to follow a standard normal distribution. is the observed ordinal variable, denoted as the consumption frequency following this equation:

where j = 0, …, M is the number of possible y outcomes where the “highest category is M. 's are unknown cut‐off values. In this study, M is equal to three. By assuming the error term to follow a standard normal distribution, the probabilities for are

where and are the standard normal probability density and cumulative distribution functions, respectively.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

The survey produced an eligible sample of 861 participants, with 47.9% of respondents (n = 412) residing in Phoenix and 52.1% (n = 449) in Detroit. Table 1 offers the summary statistics for the basic socio‐demographic characteristics of the sample. Approximately half of the participants (53%) are female, with 46% of the participants being male and 1% nonbinary gender. Participants are on average 53 years old (SD = 18). The average household size is 2.5, ranging from 1 to 10 persons, with about 19.3% of households having children. Regarding employment, 38.9% of the participants are employed full time and 7.8% are employed part‐time, while 31.2% are retired, 3.7% are students, and 4.1% are disabled. About 3.6% are unemployed not looking for work, and 4.8% either lost or furloughed their job due to COVID‐19. Several participants indicated multiple statuses, such as being employed and a student. Because we use a simple random sample design in collecting the data, our sample of respondents is subject to sampling bias. By comparison to U.S. population means, the sample collected tended to be older, higher educated, with a disproportionate percentage of White respondents, thus, the results we present are only generalizable insofar as the sample is representative of the population. Hence, rather than applying our findings more broadly, they should be interpreted with regard to this limitation.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | Survey sample | US populationa |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | ||

| Under 20 years | 0.4 | 24.9 |

| 20–24 years | 7.3 | 6.5 |

| 25–34 years | 12.3 | 13.9 |

| 35–44 years | 12.5 | 12.8 |

| 45–54 years | 16.8 | 12.4 |

| 55–59 years | 7.0 | 6.5 |

| 60–64 years | 11.5 | 6.4 |

| 65–74 years | 20.4 | 9.6 |

| 75–84 years | 10.7 | 4.9 |

| 85 years and over | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| Female | 53.0 | 50.8 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Less than high school | 1.5 | 11.4 |

| High school graduate | 13.7 | 26.9 |

| Some college | 22.5 | 20.0 |

| Two year degree | 10.6 | 8.6 |

| Four year degree | 31.9 | 20.3 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | 19.7 | 12.8 |

| White (alone) | 80.3 | 75.0 |

| Black (alone) | 11.3 | 14.2 |

| Household size (#) | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Children in household | 19.3 | 29.9 |

| Democrat | 36.9 | 27.0 |

| Republican | 29.5 | 28.0 |

| From Detroit | 52.1 | |

| From Phoenix | 47.9 | |

| Income and income shocks | ||

| Income | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 4.4 | 5.8 |

| $10,000–$49,999 | 28.4 | 32.6 |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 38.5 | 30.2 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 16.7 | 15.7 |

| More than $150,000 | 12.0 | 15.7 |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 3.6 | |

| Full time | 38.9 | |

| Part time | 7.8 | |

| Student | 3.7 | |

| Retired | 31.2 | |

| Disabled | 4.1 | |

| Furloughed due to COVID | 4.9 | |

| Received stimulus check | 69.8 | |

| Food assistance | ||

| On SNAP | 13.6 | |

| Visited food pantry within last 30 days | 8.1 | |

| Visited food pantry and on SNAP | 3.5 | |

| Shopping frequency | ||

| Shop less often | 66.0 | |

| Shop more often | 20.9 | |

| Shopping behaviors | ||

| Bought more | 46.7 | |

| Bought “what was there” | 75.0 | |

| Stockpiled | 32.7 | |

| Eating from stockpile and restocking | 55.1 | |

| Eating from stockpile without restocking | 28.3 | |

| Observations (N) | 861 | 328,239,523 |

Select categories available through the US Census American Community Survey 1‐year estimates.

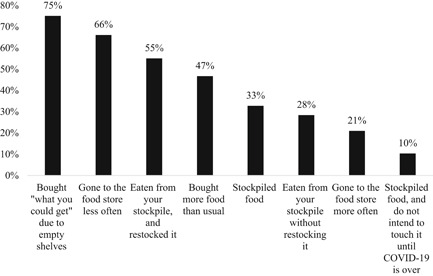

3.2. Changes in food purchasing behavior

We begin our analysis of how food shopping behaviors and patterns changed during COVID‐19, the time‐period from March until May 2020. As shown in Figure 1, 75% of the sample bought “what they can get due to empty shelves,” which is in line with reported out‐of‐stock situations at many retailers across the country. We also addressed whether people stockpiled food, or bought more than usual. Forty‐seven percent bought more food than usual and 33% stockpiled food, which is consistent with previous research conducted in March (Redman, 2020). Some 55% ate food they stockpiled but restocked it, while 28% ate from their stockpile without restocking it. Only 10% stockpiled food without the intention to touch it until the crisis is over. Aside from changes in general food shopping behavior, 66% stated to go less often to the store and 21% stated to go more often to the store. This finding is consistent with previous research which found that consumers rather not shop inside the grocery store when COVID‐19 is actively spreading (Grashuis et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Changes in food shopping behaviors during COVID‐19. Question: Since COVID‐19 started, have you… Participants could enter multiple answers. Participants could enter N/A

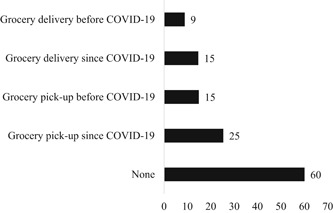

3.3. Changes in food acquisition methods

Given that two‐thirds of the sample went to the grocery store less often, the question arises whether shoppers replaced visits to the store with another shopping mode. To shed light on this, we asked respondents to indicate their level of participation in grocery delivery and pick‐up services before and since COVID‐19. Results show that, before the pandemic, 9% participated in grocery delivery and 15% in grocery pick‐up. These percentages rose to 15% and 25%, respectively, since the pandemic indicating that a fair share of consumers makes use of these services (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Participation in grocery delivery and pick‐up before and since COVID‐19 (%). Question: Have you participated in… Participants could enter multiple answers. Participants could enter N/A

Because shopping at the store was viewed as risky behavior, grocery pick‐up and delivery services saw a sudden spike in usage (Gray, 2020; Redman, 2020). To take a closer look at changes in utilization rates across pick‐up and delivery, Table 2 provides insight into the different user‐types, for instance, by differentiating whether respondents prefer pick‐up or delivery exclusively or at the same time.

Table 2.

Participation in grocery delivery and pick‐up, comparisons before and since COVID‐19

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| Households using grocery pick‐up services, only | |

| Grocery pick‐up before COVID‐19 | 4.5 |

| Grocery pick‐up before and delivery before and since COVID‐19 | 0.5 |

| Grocery pick‐up since COVID‐19 | 11.5 |

| Grocery pick‐up since and delivery before and since COVID‐19 | 0.6 |

| Percentage point increase in number of households using grocery pick‐up, only, since COVID‐19 | 7.1 |

| Households using grocery delivery services, only | |

| Grocery delivery before COVID‐19 | 2.4 |

| Grocery pick‐up before and since & delivery before COVID‐19 | 0.1 |

| Grocery delivery since COVID‐19 | 3.8 |

| Grocery pick‐up before and since and delivery since COVID‐19 | 1.2 |

| Percentage point increase in number of households using grocery delivery, only, since COVID‐19 | 1.4 |

| Households using both grocery pick‐up and delivery services | |

| Grocery pick‐up before and delivery before COVID‐19 | 0.9 |

| Grocery pick‐up since and delivery since COVID‐19 | 4.3 |

| Percentage point increase in number of households using both pick‐up and delivery, since COVID‐19 | 3.4 |

| Households who switched services | |

| Grocery pick‐up before and delivery since COVID‐19 | 0.7 |

| Grocery delivery before and pick‐up since COVID‐19 | 0.7 |

| Percentage of households who switched services | 1.4 |

| Households who remained using the same services | |

| Grocery pick‐up and delivery before and since COVID‐19 | 2.2 |

| Grocery pick‐up before and since COVID‐19 | 4.8 |

| Grocery delivery before and since COVID‐19 | 1.4 |

| Percentage of households who continued using same services | 8.4 |

| None | 60.1 |

Note: Participants could enter N/A.

Question: Have you participated in…

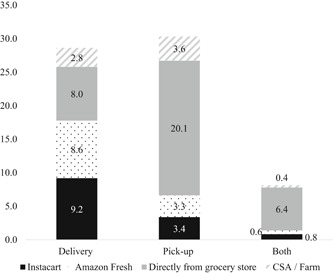

Continuing with those who use grocery delivery and/or pick‐up programs we investigated which services are most preferred (multiple answer question), shown in Figure 3. Results show a similar distribution across delivery platforms, about 8%–9% across Instacart, Amazon Fresh, and store‐direct, while only 3% indicated use of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) or farm delivery—most likely because CSAs and farms are less likely to offer delivery services. However, a stark contrast appears when looking at pick‐up programs. Twenty percent of respondents indicated they picked up groceries directly from the store, whereas only about 3% each use CSAs/Farms, Instacart, or Amazon Fresh when picking up their groceries suggesting that these options are still underutilized. For those who used both programs, over 6% preferred the grocery store over the other three services (all under 1%).

Figure 3.

Delivery and pick‐up programs used (%). Question: In which grocery delivery or grocery pick‐up programs are you participating? Participants could enter multiple answers

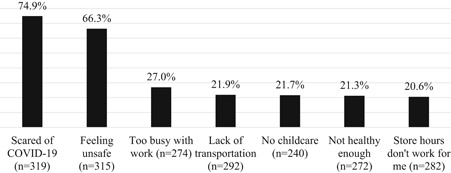

As a follow‐up question, we inquired about the reasons why shoppers participate in grocery pick‐up or delivery programs, and these responses are presented in Figure 4. Overwhelmingly, responses were related to anxiety. Some 75% stated they were scared of the pandemic and 66% said they were feeling unsafe. About one‐third mentioned that they were too busy with work. About 21% said they had no childcare or were not healthy enough. These two reasons are likely related to the virus, however, another 21% participate in the programs due to lack of transportation and store hours, which might be unrelated to COVID‐19.

Figure 4.

Reasons to participate in grocery pick‐up or delivery programs. Question: What are reasons that you participate in grocery pick‐up or delivery programs?. Participants could enter multiple answers. Participants could enter N/A. Note the category “other” (note specified) was chosen by 32.1% (n = 190)

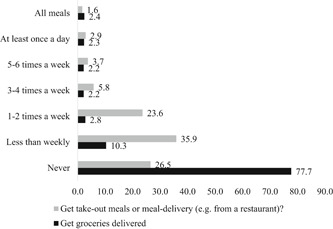

Before COVID‐19, most of those who used take‐out and delivery got meals or groceries once or twice a week or less often (see Figure 5). While more than two‐thirds of all respondents made use of take‐out meals or meal‐delivery, the opposite is true for grocery delivery, where more than two‐third never made use of these services.

Figure 5.

Take‐out and delivery usage before COVID‐19 (%). Question: Before COVID‐19, how often did you usually

As displayed in Table 3, over 50% of the sample uses grocery delivery more because of COVID‐19, the same is true for about 40% of participants when it comes to meals. Some 30% state that their usage level is about the same as before. While about 15% get fewer groceries delivered than before, over 30% get fewer meals. This is in line with the customer‐loss reported for restaurants.

Table 3.

Change in grocery delivery and take‐out during COVID‐19

| Change in | Get groceries delivered | Get take‐out meals or meal‐delivery (e.g., from a restaurant)? |

|---|---|---|

| Much less | 9.68 | 20.73 |

| Somewhat less | 4.11 | 12.1 |

| About the same | 35.19 | 27.08 |

| Somewhat more | 25.22 | 29.65 |

| Much more | 25.81 | 10.44 |

| Total n | 341 | 661 |

Note: Participants could enter N/A.

Question: How much has the following changed due to COVID‐19?

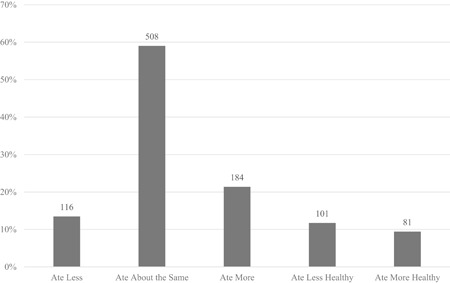

3.4. Changes in food consumption

While shifts in grocery shopping patterns during the pandemic had implications along the food supply chain, ultimately, we are interested in understanding the extent to which consumers' diets were shaped as a result. Anecdotally, many pre‐COVID‐19 consumption habits, for example, purchasing premade salads or other fresh meals and dining out, were affected because of food safety concerns and changes in working conditions. Therefore, in seeking to better understand shifts in consumption patterns, we asked respondents to indicate how the volume and quality of food consumed changed during the lockdown. When respondents were asked “How much has your diet changed since COVID‐19 started?” about 60% stated that they ate about the same amount of food as before, 13% said they ate less, and 21% said they ate more. Some 9% stated they eat healthier and 12% thought they eat less healthy (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Changes in dietary patterns during COVID‐19 (% of respondents). Question:How much has your diet changed since COVID‐19 started?. Participants could enter multiple answers. y‐axis indicates percentage of respondents who selected each response while data labels indicate number of respondents (total number of survey particiapnts = 861)

Next, we examine responses to the question “How much more or less have you consumed these foods since COVID‐19 started?” and present these results in Table 4, which shows the extent to which participants changed their volume of food consumption, ranging from eating a lot less to eating a lot more, across the 10 major food groups. Across most food groups, a majority of respondents stated that their consumption remained about the same, ranging between 50% and 70% of the sample, except for Snacks and Fast Food. Unsurprisingly, the majority of respondents (48.0%) indicated that meal take‐out decreased. However, snack consumption increased (41.9%), most likely because people were working from home more. Aside from respondents who indicated “about the same,” more people stated they ate less meat and prepped meals compared to those who stated they eat more; whereas more people stated they ate more fresh produce, dairy, grains, frozen food, canned food, and bottled water compared to those who stated they ate less.

Table 4.

Change in consumption since the beginning of COVID‐19

| (%) | Fresh produce | Dairy | Meat | Grains* | Snacks | Fast food | Frozen food | Canned food | Prepped meals | Bottled water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A lot less | 4.76 | 3.14 | 4.99 | 1.63 | 4.53 | 31.59 | 4.99 | 4.53 | 9.76 | 6.04 |

| A little less | 12.08 | 9.52 | 17.19 | 8.59 | 12.54 | 16.38 | 11.50 | 9.52 | 11.38 | 5.11 |

| About the same | 54.59 | 65.27 | 54.36 | 59.35 | 40.07 | 21.37 | 53.19 | 57.49 | 34.96 | 43.79 |

| A bit more | 16.84 | 12.54 | 13.12 | 21.02 | 28.69 | 11.61 | 17.07 | 16.72 | 11.27 | 13.36 |

| A lot more | 10.69 | 6.62 | 6.74 | 7.67 | 13.24 | 5.23 | 8.36 | 5.69 | 4.07 | 12.20 |

| Do not consume | 1.05 | 2.90 | 3.60 | 1.74 | 0.93 | 13.82 | 4.88 | 6.04 | 28.57 | 19.51 |

| Total (n) | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 | 861 |

Note: Italic denotes category with lowest share and bold denotes category with the highest share.

Question: How much more or less have you consumed these foods since COVID‐19 started?

Full description = Grains (bread, pasta, rice, etc.)

3.5. Determinants of changes in food consumption

Finally, we aim to shed light on what associations can be drawn between shopping behaviors and changes in consumption patterns during the COVID‐19 lockdown period. We estimate the ordered probit model from Section 2.3 using maximum‐likelihood, with separate models for each food category, where the dependent variable for each model is the change in consumption since the beginning of COVID‐19. In total, we estimate four model specifications, beginning with a model that only reflects demographics and income shocks due to COVID‐19, and ending with a model that includes those variables as well as shopping frequency and shopping behaviors. Ultimately, model selection was determined according to the following criteria: (1) the minimum value of the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), which scores the model based on the log‐likelihood of the model and the number of parameters in the model; and (2) comparing the predicted probabilities derived from the model and comparing them with the sample probability distributions across food categories. According to these criteria, two models best fit the data. Model 1—our “preferred” model—most closely predicted observable probabilities (see Table A1), whereas Model 4 resulted in the lowest BIC. Thus, we present the results of the preferred model in Table 5 with marginal effects presented in Table 6. The results of Model 4 are reported in appendix Tables A2 and A3.1

Table 5.

Determinants of changes in consumption since the beginning of COVID‐19 by food group

| Fresh produce | Dairy | Meats | Grains | Snacks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | −0.008*** | 0.003 | −0.005 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.003 |

| Female | −0.129 | 0.086 | −0.033 | 0.090 | −0.211** | 0.087 | 0.012 | 0.088 | 0.085 | 0.085 |

| High school graduate | 0.056 | 0.395 | −0.013 | 0.401 | −0.095 | 0.408 | 0.252 | 0.400 | −0.530 | 0.382 |

| Some college | 0.092 | 0.402 | −0.033 | 0.412 | 0.088 | 0.416 | 0.436 | 0.409 | −0.266 | 0.391 |

| Two year degree | 0.177 | 0.410 | −0.011 | 0.420 | −0.212 | 0.424 | 0.459 | 0.417 | −0.211 | 0.400 |

| Four year degree | 0.091 | 0.401 | −0.003 | 0.410 | 0.000 | 0.416 | 0.384 | 0.408 | −0.249 | 0.390 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | −0.067 | 0.407 | −0.041 | 0.417 | 0.079 | 0.421 | 0.265 | 0.414 | −0.452 | 0.396 |

| White, non‐Hispanic | 0.117 | 0.171 | 0.403** | 0.178 | −0.090 | 0.174 | 0.019 | 0.176 | 0.042 | 0.170 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 0.457** | 0.210 | 0.556** | 0.218 | 0.499** | 0.214 | 0.137 | 0.216 | 0.272 | 0.208 |

| Household size = 2 | 0.055 | 0.116 | −0.126 | 0.121 | −0.034 | 0.117 | 0.071 | 0.118 | −0.015 | 0.114 |

| Household size = 3 | −0.133 | 0.152 | 0.003 | 0.157 | 0.067 | 0.154 | −0.062 | 0.153 | 0.048 | 0.150 |

| Household size = 4 | −0.252 | 0.174 | −0.076 | 0.182 | −0.168 | 0.175 | −0.177 | 0.177 | 0.050 | 0.174 |

| Household size = 5 | −0.085 | 0.225 | 0.084 | 0.231 | 0.212 | 0.224 | −0.087 | 0.226 | −0.221 | 0.220 |

| Household size = 6 | 0.240 | 0.372 | 0.191 | 0.408 | 0.186 | 0.368 | −0.074 | 0.372 | 0.574 | 0.411 |

| Household size = 7 | −0.767 | 0.508 | −1.105** | 0.528 | 0.064 | 0.543 | −0.532 | 0.510 | −0.501 | 0.512 |

| Household size = 8 | −1.497 | 0.914 | 0.865 | 0.893 | −1.072 | 0.900 | 0.564 | 0.904 | −0.265 | 0.875 |

| Household size = 9 | −0.872 | 0.846 | −0.707 | 0.906 | −1.069 | 0.900 | −0.214 | 0.877 | −0.410 | 0.804 |

| Household size = 10 | 0.192 | 1.154 | 0.567 | 1.248 | 0.124 | 1.164 | −0.013 | 1.199 | 5.185 | 110.585 |

| Household with children | 0.559*** | 0.139 | 0.293** | 0.141 | 0.180 | 0.137 | 0.320** | 0.139 | 0.206 | 0.137 |

| Democrat | 0.067 | 0.100 | 0.047 | 0.105 | −0.095 | 0.102 | 0.034 | 0.102 | −0.059 | 0.100 |

| Republican | −0.036 | 0.103 | 0.087 | 0.108 | 0.011 | 0.103 | −0.182* | 0.105 | −0.198* | 0.102 |

| Phoenix Resident | −0.161* | 0.085 | −0.128 | 0.089 | 0.137 | 0.086 | −0.201** | 0.087 | −0.109 | 0.085 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | −0.814*** | 0.299 | −0.496 | 0.302 | −0.513* | 0.293 | 0.132 | 0.295 | 0.176 | 0.279 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | −0.603** | 0.287 | 0.030 | 0.288 | 0.063 | 0.281 | −0.097 | 0.277 | 0.122 | 0.265 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | −0.422 | 0.286 | −0.139 | 0.289 | 0.219 | 0.282 | 0.130 | 0.278 | 0.114 | 0.266 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | −0.478* | 0.281 | −0.130 | 0.286 | 0.400 | 0.279 | 0.125 | 0.274 | 0.218 | 0.263 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | −0.616** | 0.274 | −0.404 | 0.278 | 0.154 | 0.271 | −0.192 | 0.266 | 0.262 | 0.255 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | −0.418 | 0.289 | −0.078 | 0.293 | 0.126 | 0.286 | 0.147 | 0.282 | 0.515* | 0.273 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | −0.147 | 0.283 | 0.174 | 0.286 | 0.236 | 0.280 | 0.163 | 0.274 | 0.400 | 0.264 |

| $80,000–$89,999 | −0.547* | 0.300 | −0.227 | 0.306 | 0.129 | 0.297 | 0.372 | 0.294 | 0.403 | 0.281 |

| $90,000–$99,999 | −0.515* | 0.300 | −0.286 | 0.305 | −0.102 | 0.298 | 0.024 | 0.294 | 0.361 | 0.284 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | −0.320 | 0.272 | −0.002 | 0.274 | 0.234 | 0.269 | 0.170 | 0.263 | 0.561** | 0.254 |

| More than $150,000 | −0.252 | 0.280 | −0.018 | 0.283 | 0.534* | 0.278 | 0.414 | 0.273 | 0.257 | 0.261 |

| Furloughed due to COVID‐19 | −0.421** | 0.189 | 0.147 | 0.201 | 0.267 | 0.197 | 0.174 | 0.194 | 0.020 | 0.191 |

| Received stimulus check | −0.092 | 0.093 | 0.162* | 0.098 | 0.070 | 0.094 | 0.127 | 0.095 | 0.123 | 0.092 |

| On SNAP | 0.253 | 0.158 | 0.326** | 0.162 | 0.391** | 0.158 | 0.379** | 0.162 | 0.046 | 0.156 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days | 0.253 | 0.211 | 0.621*** | 0.218 | 0.215 | 0.210 | 0.308 | 0.213 | −0.330 | 0.205 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days and on SNAP | 0.516** | 0.261 | 0.543** | 0.256 | 0.185 | 0.248 | 0.082 | 0.249 | 0.192 | 0.252 |

| cut1 | −1.139*** | 0.430 | −0.783* | 0.441 | −1.050** | 0.448 | −0.982** | 0.443 | −0.977** | 0.419 |

| cut2 | 0.510 | 0.428 | 1.345*** | 0.442 | 0.652 | 0.447 | 0.920** | 0.443 | 0.209 | 0.418 |

| Pseudo R 2 | 0.049 | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.040 | 0.031 | |||||

| BIC | 1805.005 | 1553.071 | 1747.189 | 1675.747 | 1923.154 | |||||

| N | 824 | 809 | 804 | 819 | 828 | |||||

| Fast food | Frozen food | Canned food | Prepped Meals | Bottled Water | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | |

| Age | −0.012*** | 0.003 | −0.013*** | 0.003 | −0.004 | 0.003 | −0.007** | 0.003 | −0.008** | 0.003 |

| Female | 0.011 | 0.097 | −0.017 | 0.087 | −0.090 | 0.089 | −0.090 | 0.101 | −0.080 | 0.096 |

| High school graduate | −0.399 | 0.432 | −0.983** | 0.407 | −0.239 | 0.390 | −0.498 | 0.446 | 0.010 | 0.414 |

| Some college | −0.113 | 0.437 | −0.893** | 0.417 | −0.440 | 0.400 | −0.223 | 0.456 | −0.114 | 0.422 |

| Two year degree | −0.129 | 0.446 | −0.591 | 0.425 | −0.053 | 0.409 | −0.139 | 0.467 | −0.149 | 0.430 |

| Four year degree | −0.038 | 0.436 | −0.843** | 0.417 | −0.304 | 0.398 | −0.061 | 0.457 | −0.202 | 0.419 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | 0.013 | 0.445 | −0.819* | 0.422 | −0.240 | 0.404 | −0.231 | 0.463 | −0.393 | 0.427 |

| White, non‐Hispanic | −0.211 | 0.189 | 0.136 | 0.180 | 0.116 | 0.182 | −0.025 | 0.201 | 0.301 | 0.183 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 0.024 | 0.228 | 0.113 | 0.215 | 0.251 | 0.220 | 0.190 | 0.240 | 0.500** | 0.224 |

| Household size = 2 | −0.005 | 0.132 | −0.103 | 0.117 | 0.006 | 0.119 | 0.033 | 0.140 | 0.057 | 0.133 |

| Household size = 3 | 0.114 | 0.168 | −0.158 | 0.153 | −0.149 | 0.155 | −0.068 | 0.178 | 0.256 | 0.175 |

| Household size = 4 | 0.535*** | 0.190 | 0.029 | 0.178 | −0.008 | 0.178 | 0.342* | 0.202 | 0.018 | 0.195 |

| Household size = 5 | 0.143 | 0.241 | 0.093 | 0.227 | 0.244 | 0.231 | 0.370 | 0.249 | 0.535** | 0.246 |

| Household size = 6 | −0.404 | 0.439 | −0.017 | 0.360 | 0.215 | 0.379 | 0.990** | 0.468 | −0.022 | 0.420 |

| Household size = 7 | −0.163 | 0.546 | −0.934* | 0.519 | −0.894 | 0.557 | −1.007 | 0.694 | −1.007* | 0.556 |

| Household size = 8 | −5.292 | 211.596 | 0.335 | 0.965 | −0.775 | 0.872 | −0.073 | 0.827 | −0.198 | 0.932 |

| Household size = 9 | −5.128 | 304.090 | −0.380 | 0.847 | −0.336 | 0.865 | −0.736 | 1.210 | −0.885 | 0.858 |

| Household size = 10 | 5.861 | 256.711 | −0.192 | 1.157 | −0.021 | 1.185 | 0.457 | 1.137 | 0.034 | 1.173 |

| Household with children | −0.030 | 0.149 | 0.121 | 0.139 | 0.181 | 0.140 | 0.042 | 0.152 | 0.175 | 0.152 |

| Democrat | −0.159 | 0.112 | −0.006 | 0.101 | 0.243** | 0.103 | −0.111 | 0.117 | 0.275** | 0.114 |

| Republican | −0.109 | 0.116 | −0.203* | 0.105 | −0.064 | 0.106 | −0.188 | 0.121 | 0.107 | 0.114 |

| Phoenix resident | 0.282*** | 0.097 | 0.157* | 0.087 | 0.129 | 0.088 | 0.102 | 0.100 | 0.230** | 0.096 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | −0.090 | 0.310 | 0.319 | 0.290 | −0.091 | 0.293 | −0.255 | 0.320 | 0.201 | 0.319 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 0.416 | 0.290 | 0.423 | 0.278 | −0.206 | 0.283 | 0.003 | 0.304 | −0.339 | 0.300 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | −0.154 | 0.294 | 0.375 | 0.277 | −0.046 | 0.284 | −0.020 | 0.313 | −0.286 | 0.308 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 0.133 | 0.288 | 0.336 | 0.275 | −0.053 | 0.279 | −0.127 | 0.307 | −0.408 | 0.295 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | −0.056 | 0.279 | 0.450* | 0.266 | −0.177 | 0.271 | 0.151 | 0.300 | −0.361 | 0.288 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | 0.051 | 0.298 | 0.333 | 0.280 | 0.027 | 0.287 | −0.394 | 0.316 | −0.508* | 0.306 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | −0.058 | 0.289 | 0.326 | 0.272 | −0.064 | 0.279 | 0.003 | 0.306 | −0.339 | 0.295 |

| $80,000–$89,999 | −0.176 | 0.313 | 0.393 | 0.292 | 0.052 | 0.299 | −0.166 | 0.336 | −0.195 | 0.319 |

| $90,000–$99,999 | −0.402 | 0.320 | 0.323 | 0.291 | −0.135 | 0.299 | −0.300 | 0.336 | −0.549* | 0.327 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | −0.089 | 0.278 | 0.556** | 0.264 | −0.011 | 0.269 | 0.085 | 0.296 | −0.194 | 0.285 |

| More than $150,000 | −0.097 | 0.290 | 0.315 | 0.272 | −0.245 | 0.278 | −0.060 | 0.303 | −0.408 | 0.296 |

| Furloughed due to COVID‐19 | −0.018 | 0.220 | −0.049 | 0.204 | −0.066 | 0.203 | 0.355 | 0.232 | −0.121 | 0.244 |

| Received stimulus check | 0.089 | 0.105 | 0.020 | 0.094 | 0.089 | 0.096 | 0.084 | 0.108 | 0.147 | 0.106 |

| On SNAP | 0.378** | 0.163 | −0.072 | 0.159 | −0.023 | 0.159 | 0.142 | 0.174 | 0.068 | 0.171 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days | 0.070 | 0.237 | 0.006 | 0.209 | 0.368* | 0.214 | 0.301 | 0.232 | 0.513** | 0.233 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days and on SNAP | 0.049 | 0.269 | −0.344 | 0.244 | −0.133 | 0.263 | 0.715** | 0.282 | 0.488* | 0.272 |

| cut1 | −0.565 | 0.465 | −2.061*** | 0.444 | −1.367*** | 0.436 | −1.072** | 0.494 | −1.312*** | 0.457 |

| cut2 | 0.232 | 0.465 | −0.410 | 0.440 | 0.448 | 0.434 | 0.356 | 0.494 | 0.405 | 0.455 |

| Pseudo R 2 | 0.069 | 0.040 | 0.032 | 0.055 | 0.079 | |||||

| BIC | 1592.885 | 1751.941 | 1669.078 | 1424.556 | 1461.314 | |||||

| N | 719 | 791 | 782 | 595 | 673 | |||||

Note: Reference category: Male, Less than High School Educated, Hispanic (not White or Black), Single‐Person Household, Less than $10,000 Income, Employed, Did Not Receive Stimulus Check, Not Receiving Food Assistance (SNAP or Food Pantry).

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 6.

Marginal effects

| Fresh produce | Dairy | Meats | Grains | Snacks | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eat… | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| Female | 0.031 | 0.010 | −0.040 | 0.006 | 0.002 | −0.009 | 0.058 | −0.003 | −0.056 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.004 | −0.021 | −0.011 | 0.032 |

| High school graduate | −0.014 | −0.003 | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.027 | −0.003 | −0.024 | −0.056 | −0.015 | 0.071 | 0.122 | 0.078 | −0.200 |

| Some college | −0.022 | −0.006 | 0.028 | 0.006 | 0.002 | −0.009 | −0.024 | 0.000 | 0.024 | −0.088 | −0.042 | 0.130 | 0.054 | 0.049 | −0.102 |

| Two year degree | −0.041 | −0.015 | 0.056 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.063 | −0.012 | −0.051 | −0.092 | −0.047 | 0.138 | 0.041 | 0.040 | −0.081 |

| Four year degree | −0.022 | −0.006 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.080 | −0.033 | 0.113 | 0.050 | 0.046 | −0.096 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | 0.017 | 0.002 | −0.020 | 0.008 | 0.003 | −0.011 | −0.021 | 0.000 | 0.021 | −0.058 | −0.016 | 0.075 | 0.100 | 0.072 | −0.172 |

| White, non‐Hispanic | −0.029 | −0.007 | 0.036 | −0.089 | −0.004 | 0.093 | 0.024 | 0.000 | −0.024 | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0.006 | −0.010 | −0.005 | 0.016 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | −0.091 | −0.066 | 0.157 | −0.082 | −0.087 | 0.170 | −0.118 | −0.033 | 0.151 | −0.022 | −0.024 | 0.046 | −0.060 | −0.044 | 0.104 |

| Household size = 2 | −0.012 | −0.005 | 0.018 | 0.024 | 0.009 | −0.033 | 0.009 | 0.000 | −0.009 | −0.012 | −0.012 | 0.024 | 0.004 | 0.002 | −0.006 |

| Household size = 3 | 0.032 | 0.008 | −0.041 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.018 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.009 | −0.020 | −0.012 | −0.007 | 0.018 |

| Household size = 4 | 0.065 | 0.009 | −0.074 | 0.014 | 0.006 | −0.020 | 0.049 | −0.007 | −0.042 | 0.034 | 0.021 | −0.055 | −0.012 | −0.007 | 0.019 |

| Household size = 5 | 0.020 | 0.006 | −0.026 | −0.014 | −0.010 | 0.024 | −0.053 | −0.008 | 0.061 | 0.016 | 0.012 | −0.028 | 0.059 | 0.022 | −0.082 |

| Household size = 6 | −0.049 | −0.031 | 0.081 | −0.030 | −0.026 | 0.057 | −0.048 | −0.006 | 0.053 | 0.013 | 0.010 | −0.024 | −0.104 | −0.114 | 0.217 |

| Household size = 7 | 0.233 | −0.047 | −0.186 | 0.320 | −0.138 | −0.182 | −0.017 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.121 | 0.024 | −0.146 | 0.149 | 0.026 | −0.175 |

| Household size = 8 | 0.500 | −0.238 | −0.262 | −0.088 | −0.210 | 0.298 | 0.369 | −0.194 | −0.175 | −0.067 | −0.135 | 0.203 | 0.072 | 0.025 | −0.097 |

| Household size = 9 | 0.272 | −0.070 | −0.202 | 0.179 | −0.037 | −0.143 | 0.368 | −0.193 | −0.175 | 0.041 | 0.024 | −0.065 | 0.118 | 0.028 | −0.146 |

| Household size = 10 | −0.040 | −0.024 | 0.064 | −0.070 | −0.116 | 0.186 | −0.032 | −0.002 | 0.035 | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.004 | −0.169 | −0.405 | 0.574 |

| Household with children | −0.112 | −0.080 | 0.191 | −0.050 | −0.033 | 0.083 | −0.048 | −0.002 | 0.050 | −0.048 | −0.061 | 0.110 | −0.047 | −0.031 | 0.079 |

| Democrat | −0.016 | −0.005 | 0.021 | −0.009 | −0.003 | 0.012 | 0.026 | −0.002 | −0.025 | −0.006 | −0.005 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.008 | −0.022 |

| Republican | 0.009 | 0.003 | −0.011 | −0.016 | −0.007 | 0.023 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.026 | −0.058 | 0.050 | 0.024 | −0.074 |

| Phoenix resident | 0.038 | 0.012 | −0.050 | 0.025 | 0.009 | −0.033 | −0.038 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.031 | −0.066 | 0.027 | 0.014 | −0.041 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 0.192 | 0.061 | −0.254 | 0.110 | 0.006 | −0.115 | 0.179 | −0.089 | −0.090 | −0.025 | −0.017 | 0.042 | −0.052 | −0.010 | 0.062 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 0.129 | 0.071 | −0.200 | −0.005 | −0.004 | 0.009 | −0.019 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.008 | −0.028 | −0.037 | −0.006 | 0.043 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 0.082 | 0.064 | −0.146 | 0.025 | 0.012 | −0.038 | −0.064 | 0.009 | 0.055 | −0.024 | −0.017 | 0.041 | −0.034 | −0.006 | 0.040 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 0.096 | 0.068 | −0.163 | 0.024 | 0.012 | −0.035 | −0.110 | 0.003 | 0.107 | −0.023 | −0.016 | 0.039 | −0.063 | −0.015 | 0.078 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | 0.133 | 0.071 | −0.203 | 0.085 | 0.013 | −0.098 | −0.046 | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.043 | 0.012 | −0.054 | −0.075 | −0.019 | 0.094 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | 0.081 | 0.064 | −0.145 | 0.014 | 0.008 | −0.022 | −0.038 | 0.008 | 0.030 | −0.027 | −0.019 | 0.046 | −0.132 | −0.059 | 0.191 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | 0.024 | 0.029 | −0.054 | −0.026 | −0.027 | 0.053 | −0.069 | 0.009 | 0.059 | −0.030 | −0.022 | 0.052 | −0.108 | −0.039 | 0.147 |

| $80,000–$89,999 | 0.114 | 0.070 | −0.184 | 0.044 | 0.016 | −0.059 | −0.039 | 0.008 | 0.031 | −0.060 | −0.065 | 0.124 | −0.109 | −0.039 | 0.148 |

| $90,000–$99,999 | 0.105 | 0.069 | −0.174 | 0.057 | 0.016 | −0.073 | 0.033 | −0.011 | −0.022 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.007 | −0.099 | −0.033 | 0.132 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 0.059 | 0.055 | −0.113 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.068 | 0.009 | 0.059 | −0.031 | −0.023 | 0.054 | −0.141 | −0.068 | 0.209 |

| More than $150,000 | 0.044 | 0.046 | −0.090 | 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.005 | −0.139 | −0.011 | 0.150 | −0.065 | −0.075 | 0.140 | −0.073 | −0.019 | 0.092 |

| Furloughed due to COVID‐19 | 0.117 | −0.001 | −0.116 | −0.026 | −0.014 | 0.041 | −0.067 | −0.009 | 0.077 | −0.027 | −0.032 | 0.059 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.007 |

| Received stimulus check | 0.022 | 0.008 | −0.029 | −0.032 | −0.009 | 0.041 | −0.020 | 0.001 | 0.018 | −0.023 | −0.018 | 0.041 | −0.031 | −0.015 | 0.046 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days | −0.054 | −0.030 | 0.084 | −0.081 | −0.096 | 0.176 | −0.044 | 0.002 | 0.042 | −0.036 | −0.041 | 0.077 | 0.075 | 0.020 | −0.096 |

| On SNAP | −0.055 | −0.029 | 0.084 | −0.051 | −0.032 | 0.083 | −0.089 | −0.016 | 0.105 | −0.049 | −0.067 | 0.115 | −0.020 | −0.011 | 0.031 |

| Fast food | Frozen food | Canned food | Prepped meals | Bottled water | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eat… | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More | Less | Same | More |

| Age | 0.004 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.003 |

| Female | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.020 | 0.006 | −0.027 | 0.029 | −0.005 | −0.024 | 0.016 | 0.009 | −0.025 |

| High school graduate | 0.140 | −0.048 | −0.092 | 0.168 | 0.179 | −0.348 | 0.045 | 0.033 | −0.079 | 0.164 | −0.035 | −0.129 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.004 |

| Some college | 0.041 | −0.011 | −0.029 | 0.145 | 0.177 | −0.321 | 0.093 | 0.042 | −0.136 | 0.069 | −0.005 | −0.064 | 0.020 | 0.018 | −0.039 |

| Two year degree | 0.046 | −0.013 | −0.033 | 0.078 | 0.144 | −0.221 | 0.009 | 0.009 | −0.018 | 0.042 | −0.001 | −0.041 | 0.027 | 0.023 | −0.050 |

| Four year degree | 0.014 | −0.004 | −0.010 | 0.132 | 0.174 | −0.306 | 0.060 | 0.038 | −0.098 | 0.018 | 0.001 | −0.018 | 0.038 | 0.029 | −0.067 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | −0.005 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.126 | 0.172 | −0.298 | 0.046 | 0.033 | −0.079 | 0.071 | −0.005 | −0.066 | 0.081 | 0.044 | −0.125 |

| White, non‐Hispanic | 0.077 | −0.021 | −0.056 | −0.034 | −0.007 | 0.041 | −0.027 | −0.006 | 0.033 | 0.008 | −0.001 | −0.007 | −0.067 | −0.023 | 0.090 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | −0.009 | 0.003 | 0.006 | −0.026 | −0.010 | 0.036 | −0.051 | −0.028 | 0.079 | −0.059 | 0.005 | 0.054 | −0.083 | −0.089 | 0.172 |

| Household size = 2 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.024 | 0.008 | −0.033 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.009 | −0.012 | −0.006 | 0.018 |

| Household size = 3 | −0.042 | 0.014 | 0.028 | 0.038 | 0.011 | −0.049 | 0.036 | 0.007 | −0.042 | 0.023 | −0.006 | −0.017 | −0.050 | −0.035 | 0.085 |

| Household size = 4 | −0.197 | 0.043 | 0.155 | −0.007 | −0.003 | 0.010 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.002 | −0.105 | 0.006 | 0.100 | −0.004 | −0.002 | 0.006 |

| Household size = 5 | −0.053 | 0.017 | 0.036 | −0.020 | −0.011 | 0.031 | −0.048 | −0.031 | 0.079 | −0.113 | 0.004 | 0.109 | −0.089 | −0.095 | 0.184 |

| Household size = 6 | 0.138 | −0.060 | −0.079 | 0.004 | 0.002 | −0.005 | −0.043 | −0.026 | 0.069 | −0.239 | −0.095 | 0.334 | 0.005 | 0.002 | −0.007 |

| Household size = 7 | 0.058 | −0.023 | −0.036 | 0.295 | −0.080 | −0.216 | 0.280 | −0.098 | −0.182 | 0.367 | −0.210 | −0.157 | 0.312 | −0.095 | −0.217 |

| Household size = 8 | 0.419 | −0.247 | −0.172 | −0.063 | −0.054 | 0.118 | 0.235 | −0.068 | −0.167 | 0.025 | −0.007 | −0.018 | 0.048 | 0.010 | −0.058 |

| Household size = 9 | 0.419 | −0.247 | −0.172 | 0.102 | 0.009 | −0.110 | 0.088 | 0.001 | −0.089 | 0.271 | −0.139 | −0.132 | 0.267 | −0.066 | −0.201 |

| Household size = 10 | −0.581 | −0.247 | 0.828 | 0.047 | 0.012 | −0.059 | 0.005 | 0.002 | −0.006 | −0.136 | −0.002 | 0.138 | −0.007 | −0.003 | 0.011 |

| Household with children | 0.011 | −0.003 | −0.008 | −0.028 | −0.011 | 0.039 | −0.039 | −0.017 | 0.056 | −0.014 | 0.002 | 0.012 | −0.034 | −0.024 | 0.058 |

| Democrat | 0.057 | −0.018 | −0.039 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.002 | −0.053 | −0.021 | 0.074 | 0.036 | −0.007 | −0.030 | −0.054 | −0.037 | 0.090 |

| Republican | 0.039 | −0.012 | −0.027 | 0.051 | 0.011 | −0.062 | 0.015 | 0.004 | −0.019 | 0.062 | −0.013 | −0.049 | −0.021 | −0.013 | 0.034 |

| Phoenix resident | −0.102 | 0.031 | 0.071 | −0.038 | −0.012 | 0.049 | −0.029 | −0.009 | 0.038 | −0.033 | 0.005 | 0.028 | −0.047 | −0.027 | 0.073 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 0.033 | −0.010 | −0.023 | −0.091 | 0.006 | 0.086 | 0.020 | 0.008 | −0.028 | 0.085 | −0.020 | −0.065 | −0.025 | −0.048 | 0.073 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | −0.152 | 0.027 | 0.125 | −0.117 | −0.002 | 0.118 | 0.047 | 0.013 | −0.060 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.056 | −0.116 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 0.056 | −0.018 | −0.038 | −0.105 | 0.002 | 0.103 | 0.010 | 0.004 | −0.014 | 0.006 | −0.001 | −0.006 | 0.049 | 0.050 | −0.099 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | −0.049 | 0.012 | 0.036 | −0.096 | 0.005 | 0.091 | 0.011 | 0.005 | −0.016 | 0.041 | −0.007 | −0.034 | 0.075 | 0.063 | −0.138 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | 0.020 | −0.006 | −0.014 | −0.123 | −0.004 | 0.127 | 0.040 | 0.012 | −0.052 | −0.045 | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.064 | 0.058 | −0.123 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | −0.019 | 0.005 | 0.014 | −0.095 | 0.005 | 0.090 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 0.008 | 0.135 | −0.040 | −0.095 | 0.098 | 0.069 | −0.167 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | 0.021 | −0.006 | −0.015 | −0.093 | 0.005 | 0.088 | 0.014 | 0.006 | −0.020 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.056 | −0.116 |

| $80,000–$89,999 | 0.064 | −0.021 | −0.043 | −0.110 | 0.001 | 0.109 | −0.010 | −0.006 | 0.017 | 0.054 | −0.010 | −0.044 | 0.032 | 0.037 | −0.068 |

| $90,000–$99,999 | 0.142 | −0.053 | −0.089 | −0.093 | 0.005 | 0.087 | 0.030 | 0.011 | −0.041 | 0.101 | −0.026 | −0.075 | 0.108 | 0.071 | −0.179 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 0.032 | −0.010 | −0.022 | −0.146 | −0.017 | 0.163 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.004 | −0.026 | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.031 | 0.037 | −0.068 |

| More than $150,000 | 0.036 | −0.011 | −0.024 | −0.090 | 0.006 | 0.085 | 0.057 | 0.013 | −0.071 | 0.019 | −0.003 | −0.017 | 0.075 | 0.063 | −0.137 |

| Furloughed due to COVID‐19 | 0.006 | −0.002 | −0.004 | 0.012 | 0.003 | −0.015 | 0.015 | 0.004 | −0.019 | −0.104 | −0.002 | 0.106 | 0.026 | 0.012 | −0.038 |

| Received Stimulus Check | −0.032 | 0.010 | 0.022 | −0.005 | −0.001 | 0.006 | −0.020 | −0.006 | 0.026 | −0.027 | 0.005 | 0.022 | −0.031 | −0.015 | 0.046 |

| Visited Food Pantry in past 30 days | −0.005 | 0.006 | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.002 | −0.010 | −0.059 | −0.040 | 0.099 | −0.100 | −0.004 | 0.104 | −0.081 | −0.094 | 0.174 |

| On SNAP | −0.128 | 0.031 | 0.096 | 0.023 | 0.006 | −0.029 | 0.011 | 0.008 | −0.020 | −0.050 | 0.001 | 0.049 | −0.013 | −0.006 | 0.019 |

Note: Bold indicates significance at the 90% confidence level at least. Reference category: Male, Less than High School Educated, Hispanic (not White or Black), Single‐Person Household, Less than $10,000 Income, Employed, Did Not Receive Stimulus Check, Not Receiving Food Assistance (SNAP or Food Pantry).

3.5.1. Estimation results

The results in Table 5 describe the determinants of whether a consumer was more likely to move from one consumption amount to another since COVID‐19 across each food group. Results from Table 5 can only be interpreted insofar as the significance and the sign; therefore, we focus our findings section on the marginal effects in Table 6. Notably, findings show that associations between changes in food consumption and the presence of children in the household, race, and residency are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level at least. During COVID‐19, respondents with children in the household were more likely to consume more fresh produce (19.1%), dairy (8.3%), and grains (11.0%). Individuals who identify as Black or African American (non‐Hispanic) were more likely to consume more fresh produce (15.7%), dairy (17.0%), meat (15.1%), and bottled water (17.2%). Compared to Detroit residents, Phoenix residents were more likely to consume less fresh produce (3.8%) and grains (3.5%), but more likely to consume more frozen food (4.9%).2 With respect to income and income shocks, we find little statistical significance across food categories, with the exception of fast food consumption. Those who were furloughed or lost their job due to COVID‐19 were 11.7% more likely to indicate consuming less fresh produce. In addition, the association between the utilization of food assistance programs and consumption of dairy, meat, and grain consumption is statistically significant. Respondents on SNAP were more likely to consume more of these three food groups (8.3%, 10.5%, and 11.5%, respectively). Additionally, respondents who visited a food pantry within the past thirty days were less likely to indicate consuming less canned food (−5.9%), prepped meals (−10.0%), and bottled water (−8.1%). These results are consistent with those from Model 4 (Appendix Table A3).

3.5.2. Robustness check

Due to concerns about potential common factors that might affect both purchase and consumption changes, we reserve Model 4 results only as a robustness check. However, when adding variables that account for shopping frequency and dietary patterns, the results from Models 1 and 4 are robust, as the sign, scale, and significance of the results obtained from Model 1 and discussed in Section 3.5.1 are largely the same. Nonetheless, additional covariates yield several statistically significant findings. Respondents who shopped more often were more likely to consume more dairy (8.2%), grains (16.0%), frozen food (8.9%), and bottled water (12.4%). Unsurprisingly, those who indicated buying more were more likely to consume more of each food category, except fast food (7.8% more likely to consume less). Finally, respondents who indicated stockpiling were more likely to consume more dairy (5.6%), meat (8.8%), frozen food (9.0%), and canned food (9.7%).

4. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

This study aimed to shed light on food purchasing behaviors, acquisition methods, and consumption during the pandemic. In this section, we synthesize our findings as they pertain to food retailers, food manufacturers, and other food industry stakeholders in navigating this new terrain.

First, based on the observed interest in grocery delivery and pick‐up services, there is an opportunity for retailers to sustain market share if they offer these programs or partner with existing services like Instacart. Retailers that have more robust logistics in place may be more prepared to seamlessly integrate grocery delivery, offering it as a permanent service, as delivery and pick‐up services will continue to grow in popularity as a shopping mode for many consumers. Second, as many respondents indicated, they purchased “what they could” when shopping, so it would serve food manufacturers who are focused on capital efficiency to establish a presence in many types of stores to increase brand exposure. Because of channel agnosticism among consumers, brand continuity is crucial, hence, food manufacturers would need to build a flexible back end to offer products more ubiquitously. Finally, over half of respondents indicated some form of stockpiling food. This evidence of insecurity in the food supply chain should be noted and key considerations must be made to ensuring food safety and re‐establishing trust in the food system.

As with any research conducted during this time, shopping patterns and consumption behaviors will continue to evolve, in some cases reverting to pre‐COVID‐19 norms. For instance, some customers might simply prefer to not go into the store during the pandemic but want to keep shopping at their preferred store, ensuring they receive their favorite products. Nevertheless, the commerce that surrounds the food industry is a crucial component of the economy whose revival is dependent on consumers' sentiments and trust in the food system. How consumers navigate food‐purchasing decisions in times of uncertainty has important consequences for both food retailers and food manufacturers. Emerging from the pandemic, it will be critical to understand these behaviors to retain customers in the long‐term. COVID‐19 has already proven to be a disruptive event that will shape the future of the food industry, much in line with other disruptors such as standardization, technological innovation, the introduction of new store formats, and the intensified interest among antitrust authorities concerning mergers and acquisitions across chains. Based on our results, we cannot determine what lies ahead in the long‐run, but uncertainty and risk exposure have shaped the way in which consumers shopped and what they ate. For agribusiness, this event has heightened awareness regarding the cyclical nature of food markets, particularly for food retail and food manufacturing.

5. CONCLUSION

To develop a deeper understanding of consumers' food shopping and consumption behavior during the COVID‐19 pandemic, we conducted an online survey in 2020 during the first wave of COVID‐19 in two major metropolitan areas in the United States. The results that follow should be interpreted insofar as they pertain to the study sites, namely Detroit, MI, and Phoenix, AZ. With regard to food shopping, we found that about three‐quarters of respondents were buying the food they could get due to out‐of‐stock situations, and about half the participants bought more food than usual even though the majority went to the food store less frequently. Consumers also tended to purchase more groceries than normal during their shopping trips while buying what was available due to stock‐outs of commonly used and popular items. It comes as no surprise that consumers in the study areas attempted to avoid shopping during the beginning of the pandemic when no clear rules, such as wearing masks, having plastic shields for cashiers, and floor stickers that indicate six feet distance, were yet in place.

With regard to online grocery shopping since the COVID‐19 pandemic, we found a 255% increase (from 4.5% to 11.5%) in the number of respondents that use grocery pickup as a shopping method. At the same time, there was a 158% increase in the number of households that utilize grocery delivery services. The surge in grocery pickup and delivery program participation could be explained mainly by consumers fearing COVID‐19 (74.9%) and feeling unsafe (66.3%). However, while participants in Phoenix and Detroit were almost equally likely to order their groceries being delivered by Instacart, Amazon Fresh or grocery stores, the most popular outlet for grocery pick‐up was directly from the supermarket. Therefore, to maintain such drastic growth in grocery pick‐up after the threat of a virus diminishes, grocery stores have to ensure the quality and reliability of the services provided during the coronavirus outbreak. As a result, consumers' preference for a safe and reliable mode of grocery acquisition may be sustained.

Food consumption patterns were also of interest to us, as they offer key insights for food retailers and manufacturers who must adapt their inventory to satisfy imminent consumer demand. While food consumption patterns seemed to stay the same for the majority of our participants, some indicated that they had been consuming more food since the beginning of the pandemic. On the extensive margin, our results confirm an overwhelming shift away from consumption away from home (e.g., fast food) to snack food consumption. On the intensive margin, we found an increase in the consumption of fresh produce and dairy among households with children, and an increase in frozen foods and bottled water among households who were shopping more and purchasing more.

At the time of writing, the world is preparing for a “second wave” of the virus. With both improved surveillance policies (e.g., virus and antibody testing) and more stringent monitoring policies (e.g., temperature checks, local mandates to wear masks) in place, cities are better prepared not only to withstand subsequent outbreaks of the virus but also to endure strains placed on the food system at its expense. Many hope, and even take comfort, that life will return to the pre‐COVID‐19 norms, and, in the short‐run, some reports indicate that consumer shopping is normalizing (CFI, NPD). However, other factors, such as rising food prices, may affect shopping behaviors, as agricultural labor markets face shortages and distribution channels remain tightened. In addition, the crisis has exposed significant inequities in the landscape for food retail. Future research could examine how the changes incurred would exacerbate some of the already heavy burdens on areas with food access challenges and a high proportion of food‐insecure households.

To close, this study is not without limitations. First, we focused on two major metropolitan areas in the United States, and thus the results are only generalizable to the extent that the sample is representative of the U.S. population. Future research could expand this to a nationwide survey and could also investigate food shopping and consumption in rural areas. Also, behavior in other countries likely differs, which is of interest to the food supply chain in a global marketplace. Second, we conducted our survey at a time when stay‐at‐home orders were being lifted. Hence, behavior might have been affected by this. Finally, as with all survey work, we rely on the recall ability of our participants which may lack accuracy. Future studies could employ other methods, such as analysis using revealed preference, that is, scanner data to supplement the findings of this study.

Biographies

Dr. Lauren Chenarides is an Assistant Professor in the Morrison School of Agribusiness at the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University, 7231 E Sonoran Arroyo Mall, Mesa, AZ. She earned a B.A. in Mathematics from the College of the Holy Cross in 2008 and a Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics from Penn State University in 2017. Lauren Chenarides studies trends and developments in food retailer competition and market concentration, contemporary food policy issues, and the consequences of poor food access on consumer spending.

Dr. Carola Grebitus is an Associate Professor of Food Industry Management in the Morrison School of Agribusiness at the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University, 7231 E Sonoran Arroyo Mall, Mesa, AZ. She earned a B.S. in Food Science from Kiel University in 2001, a M.S. in Food Economics from Kiel University in 2002, and a Ph.D. in Agricultural Science from Kiel University in 2007. Carola Grebitus studies healthy and sustainable food choices with an emphasis on behavioral and experimental economics.

Dr. Jayson L. Lusk is a Distinguished Professor and Head in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Purdue University, 403 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN. He earned a B.S. in Food Technology from Texas Tech in 1997 and a Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics from Kansas State University in 2000. Jayson Lusk studies what we eat and why we eat it.

Dr. Iryna Printezis is an Assistant Clinical Professor at the Department of Supply Chain Management of the W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University. She earned a M.S. in Industrial Engineering from the Ukrainian State Chemical Engineering University in 2008, and a Ph.D. in Agribusiness (Business Administration) from Arizona State University in 2018. Dr. Printezis studies consumer demand and behavior, food attributes and labeling, public policies, and their implications.

See Appendix (Tables A1, A2, A3)

Table A1.

Predicted probabilities compared to actual probabilities

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Actual (%) | Predicted (%) | Predicted (%) | Predicted (%) | Predicted (%) | |

| Fresh produce | ||||||

| Eat Less | 145 | 17.02 | 16.80 | 16.92 | 16.54 | 16.42 |

| Eat the Same | 470 | 55.16 | 55.47 | 55.63 | 54.51 | 55.03 |

| Eat More | 237 | 27.82 | 27.73 | 27.45 | 28.95 | 28.55 |

| 852 | ||||||

| Dairy | ||||||

| Eat Less | 109 | 13.04 | 12.19 | 12.17 | 13.31 | 13.12 |

| Eat the Same | 562 | 67.22 | 67.96 | 68.41 | 67.62 | 68.29 |

| Eat More | 165 | 19.74 | 19.85 | 19.43 | 19.07 | 18.59 |

| 836 | ||||||

| Meats | ||||||

| Eat Less | 191 | 23.01 | 22.20 | 22.43 | 21.89 | 21.70 |

| Eat the Same | 468 | 56.39 | 56.79 | 57.35 | 56.77 | 57.98 |

| Eat More | 171 | 20.60 | 21.01 | 20.22 | 21.34 | 20.32 |

| 830 | ||||||

| Grains | ||||||

| Eat Less | 88 | 10.40 | 10.32 | 10.37 | 10.49 | 10.51 |

| Eat the Same | 511 | 60.40 | 60.63 | 60.65 | 59.94 | 60.30 |

| Eat More | 247 | 29.20 | 29.05 | 28.98 | 29.57 | 29.18 |

| 846 | ||||||

| Snacks | ||||||

| Eat Less | 147 | 17.23 | 17.00 | 16.96 | 15.96 | 16.11 |

| Eat the Same | 345 | 40.45 | 40.33 | 39.83 | 39.87 | 40.07 |

| Eat More | 361 | 42.32 | 42.67 | 43.20 | 44.17 | 43.82 |

| 853 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Actual (%) | Predicted (%) | Predicted (%) | Predicted (%) | Predicted (%) | |

| Fast food | ||||||

| Eat Less | 413 | 55.66 | 55.74 | 56.51 | 55.85 | 56.23 |

| Eat the Same | 184 | 24.80 | 25.02 | 24.35 | 25.34 | 25.11 |

| Eat More | 145 | 19.54 | 19.24 | 19.15 | 18.81 | 18.66 |

| 742 | ||||||

| Frozen food | ||||||

| Eat Less | 142 | 17.34 | 17.03 | 16.64 | 16.96 | 16.77 |

| Eat the Same | 458 | 55.92 | 56.22 | 56.35 | 55.06 | 55.68 |

| Eat More | 219 | 26.74 | 26.76 | 27.00 | 27.99 | 27.55 |

| 819 | ||||||

| Canned food | ||||||

| Eat Less | 121 | 14.96 | 15.21 | 15.09 | 15.71 | 15.52 |

| Eat the Same | 495 | 61.19 | 61.16 | 61.26 | 60.10 | 60.63 |

| Eat More | 193 | 23.86 | 23.63 | 23.64 | 24.19 | 23.85 |

| 809 | ||||||

| Prepped meals | ||||||

| Eat Less | 182 | 29.59 | 30.27 | 30.45 | 30.74 | 30.82 |

| Eat the Same | 301 | 48.94 | 49.03 | 48.65 | 48.52 | 48.49 |

| Eat More | 132 | 21.46 | 20.71 | 20.90 | 20.74 | 20.68 |

| 615 | ||||||

| Bottled water | ||||||

| Eat Less | 96 | 13.85 | 14.41 | 14.64 | 14.75 | 14.82 |

| Eat the Same | 377 | 54.40 | 54.92 | 55.83 | 54.64 | 55.77 |

| Eat More | 220 | 31.75 | 30.67 | 29.54 | 30.60 | 29.41 |

| 693 |

Table A2.

Robustness check, determinants of changes in consumption since the beginning of COVID‐19 by food group

| Fresh produce | Dairy | Meats | Grains | Snacks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | |

| Age | 0.007** | 0.004 | 0.011*** | 0.004 | −0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Female | −0.105 | 0.098 | −0.060 | 0.104 | −0.149 | 0.101 | −0.093 | 0.101 | −0.027 | 0.098 |

| High school graduate | −0.035 | 0.490 | −0.446 | 0.518 | −0.853 | 0.535 | 0.263 | 0.521 | −0.501 | 0.487 |

| Some college | −0.087 | 0.494 | −0.549 | 0.527 | −0.657 | 0.543 | 0.343 | 0.528 | −0.270 | 0.493 |

| Two year degree | 0.052 | 0.505 | −0.563 | 0.537 | −0.940* | 0.551 | 0.376 | 0.538 | −0.231 | 0.505 |

| Four year degree | 0.024 | 0.495 | −0.543 | 0.526 | −0.822 | 0.543 | 0.259 | 0.528 | −0.272 | 0.493 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | −0.128 | 0.500 | −0.561 | 0.532 | −0.723 | 0.548 | 0.115 | 0.534 | −0.538 | 0.499 |

| White, non‐Hispanic | 0.132 | 0.185 | 0.398** | 0.194 | 0.007 | 0.191 | 0.011 | 0.195 | 0.176 | 0.185 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 0.524** | 0.236 | 0.508** | 0.242 | 0.468* | 0.242 | −0.060 | 0.244 | 0.373 | 0.234 |

| Household size = 2 | 0.084 | 0.130 | −0.096 | 0.138 | −0.122 | 0.133 | 0.002 | 0.135 | −0.120 | 0.130 |

| Household size = 3 | 0.050 | 0.174 | 0.112 | 0.181 | −0.103 | 0.178 | −0.147 | 0.178 | −0.054 | 0.173 |

| Household size = 4 | −0.203 | 0.200 | −0.031 | 0.209 | −0.306 | 0.203 | −0.229 | 0.205 | −0.073 | 0.203 |

| Household size = 5 | −0.034 | 0.251 | 0.222 | 0.260 | 0.176 | 0.256 | −0.096 | 0.256 | −0.573** | 0.248 |

| Household size = 6 | 0.355 | 0.471 | 0.013 | 0.470 | −0.004 | 0.466 | −0.414 | 0.460 | 0.311 | 0.516 |

| Household size = 7 | −0.328 | 0.736 | −0.022 | 0.765 | −0.292 | 0.748 | −0.398 | 0.722 | −0.519 | 0.736 |

| Household size = 8 | −6.069 | 126.515 | 4.598 | 122.730 | −6.823 | 124.073 | 4.321 | 127.684 | 4.402 | 112.397 |

| Household size = 9 | −0.432 | 0.880 | −0.412 | 0.952 | −1.453 | 0.997 | 0.216 | 0.926 | −0.139 | 0.839 |

| Household size = 10 | −0.153 | 1.189 | 0.306 | 1.303 | −0.072 | 1.218 | −0.899 | 1.254 | 4.813 | 112.395 |

| Household with children | 0.588*** | 0.158 | 0.410** | 0.162 | 0.376** | 0.159 | 0.392** | 0.161 | 0.223 | 0.158 |

| Democrat | 0.031 | 0.115 | 0.015 | 0.122 | −0.089 | 0.118 | −0.131 | 0.119 | −0.108 | 0.116 |

| Republican | −0.095 | 0.118 | 0.030 | 0.124 | 0.071 | 0.120 | −0.427*** | 0.123 | −0.289** | 0.118 |

| Phoenix resident | −0.104 | 0.096 | −0.167 | 0.102 | 0.115 | 0.099 | −0.209** | 0.100 | −0.156 | 0.097 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | −0.841** | 0.365 | −0.431 | 0.377 | −0.429 | 0.377 | 0.157 | 0.365 | −0.040 | 0.347 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | −0.618* | 0.348 | −0.013 | 0.355 | 0.089 | 0.357 | −0.006 | 0.341 | −0.083 | 0.326 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | −0.469 | 0.355 | −0.247 | 0.364 | 0.173 | 0.369 | −0.036 | 0.348 | −0.112 | 0.336 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | −0.584* | 0.342 | −0.149 | 0.355 | 0.440 | 0.358 | 0.099 | 0.339 | −0.002 | 0.324 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | −0.775** | 0.333 | −0.560 | 0.345 | 0.111 | 0.347 | −0.225 | 0.328 | 0.177 | 0.315 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | −0.474 | 0.350 | −0.192 | 0.362 | 0.150 | 0.366 | 0.063 | 0.347 | 0.396 | 0.336 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | −0.171 | 0.344 | 0.065 | 0.355 | 0.321 | 0.360 | 0.100 | 0.340 | 0.242 | 0.326 |

| $80,000–$89,999 | −0.653* | 0.360 | −0.223 | 0.373 | 0.090 | 0.373 | 0.498 | 0.357 | 0.230 | 0.340 |

| $90,000–$99,999 | −0.537 | 0.367 | −0.213 | 0.380 | −0.029 | 0.383 | 0.141 | 0.365 | 0.116 | 0.350 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | −0.520 | 0.333 | −0.212 | 0.343 | 0.130 | 0.347 | 0.065 | 0.327 | 0.407 | 0.315 |

| More than $150,000 | −0.400 | 0.343 | −0.157 | 0.355 | 0.414 | 0.358 | 0.256 | 0.340 | 0.078 | 0.325 |

| Furloughed due to COVID‐19 | −0.158 | 0.226 | 0.042 | 0.244 | 0.377 | 0.240 | 0.001 | 0.236 | 0.246 | 0.239 |

| Received stimulus check | −0.126 | 0.105 | 0.087 | 0.111 | 0.015 | 0.107 | 0.010 | 0.107 | 0.054 | 0.104 |

| On SNAP | 0.212 | 0.180 | 0.211 | 0.183 | 0.356** | 0.182 | 0.282 | 0.185 | −0.046 | 0.178 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days | 0.331 | 0.243 | 0.632** | 0.252 | 0.370 | 0.242 | 0.534** | 0.252 | −0.407* | 0.233 |

| Visited food pantry in past 30 days and on SNAP | 0.344 | 0.312 | 0.487 | 0.314 | 0.292 | 0.307 | −0.119 | 0.301 | −0.068 | 0.306 |

| Shopped less often | −0.033 | 0.118 | −0.075 | 0.125 | −0.118 | 0.121 | 0.264** | 0.122 | 0.100 | 0.116 |

| Shopped more often | 0.218 | 0.145 | 0.322** | 0.150 | 0.226 | 0.146 | 0.497*** | 0.150 | 0.182 | 0.144 |

| Bought more | 0.453*** | 0.104 | 0.479*** | 0.111 | 0.476*** | 0.107 | 0.641*** | 0.109 | 0.563*** | 0.104 |

| Bought what was there | −0.284** | 0.112 | −0.339*** | 0.120 | −0.233** | 0.115 | −0.081 | 0.115 | −0.050 | 0.111 |

| Stockpiled | 0.120 | 0.112 | 0.232* | 0.119 | 0.354*** | 0.115 | −0.026 | 0.117 | 0.109 | 0.114 |

| Ate from stockpile and restocked | 0.038 | 0.104 | −0.021 | 0.111 | −0.078 | 0.107 | 0.132 | 0.108 | 0.075 | 0.105 |

| Ate from stockpile without restocking | −0.064 | 0.107 | 0.008 | 0.113 | −0.042 | 0.110 | 0.141 | 0.111 | 0.044 | 0.108 |

| cut1 | −1.046* | 0.541 | −0.879 | 0.571 | −1.517** | 0.592 | −0.537 | 0.581 | −0.976* | 0.537 |

| cut2 | 0.672 | 0.539 | 1.381** | 0.571 | 0.355 | 0.589 | 1.514*** | 0.583 | 0.292 | 0.536 |

| Pseudo R 2 | 0.088 | 0.102 | 0.120 | 0.110 | 0.078 | |||||

| BIC | 1499.541 | 1289.967 | 1410.421 | 1363.610 | 1568.069 | |||||

| N | 667 | 656 | 647 | 663 | 669 | |||||

| Fast food | Frozen food | Canned food | Prepped meals | Bottled water | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | Coef. | SD | |

| Age | −0.005 | 0.004 | −0.010*** | 0.004 | −0.005 | 0.004 | −0.005 | 0.004 | −0.008* | 0.004 |

| Female | −0.014 | 0.112 | −0.065 | 0.100 | −0.213** | 0.102 | −0.103 | 0.114 | −0.067 | 0.110 |

| High school graduate | −0.667 | 0.531 | −1.451*** | 0.545 | −0.418 | 0.505 | −1.088* | 0.594 | 0.132 | 0.521 |

| Some college | −0.424 | 0.533 | −1.382** | 0.553 | −0.685 | 0.512 | −0.855 | 0.600 | −0.030 | 0.528 |

| Two year degree | −0.373 | 0.546 | −1.188** | 0.563 | −0.309 | 0.523 | −0.762 | 0.610 | 0.004 | 0.538 |

| Four year degree | −0.293 | 0.533 | −1.377** | 0.554 | −0.540 | 0.512 | −0.689 | 0.601 | −0.144 | 0.525 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | −0.338 | 0.539 | −1.356** | 0.559 | −0.497 | 0.517 | −0.880 | 0.608 | −0.310 | 0.533 |

| White, non‐Hispanic | −0.279 | 0.204 | 0.245 | 0.196 | 0.301 | 0.196 | 0.108 | 0.213 | 0.391* | 0.201 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | −0.116 | 0.255 | 0.068 | 0.242 | 0.433* | 0.247 | 0.285 | 0.267 | 0.561** | 0.253 |

| Household size = 2 | 0.014 | 0.152 | −0.150 | 0.132 | −0.022 | 0.135 | 0.092 | 0.160 | 0.048 | 0.151 |

| Household size = 3 | 0.190 | 0.196 | −0.190 | 0.174 | −0.223 | 0.177 | 0.164 | 0.201 | 0.238 | 0.198 |

| Household size = 4 | 0.451** | 0.227 | −0.087 | 0.204 | −0.082 | 0.205 | 0.557** | 0.230 | 0.166 | 0.227 |

| Household size = 5 | 0.154 | 0.276 | −0.037 | 0.253 | 0.118 | 0.259 | 0.582** | 0.283 | 0.758*** | 0.281 |

| Household size = 6 | −0.420 | 0.548 | −0.208 | 0.446 | −0.119 | 0.451 | 0.966* | 0.508 | −0.440 | 0.488 |

| Household size = 7 | −0.543 | 0.832 | −1.198 | 0.740 | −0.923 | 0.735 | −0.634 | 0.805 | −0.710 | 0.727 |

| Household size = 8 | −5.318 | 336.912 | 3.013 | 126.995 | 3.842 | 125.290 | −0.624 | 1.330 | 3.577 | 128.468 |

| Household size = 9 | −5.207 | 336.911 | −0.688 | 0.888 | −0.525 | 0.906 | −0.891 | 1.300 | −0.174 | 0.907 |

| Household size = 10 | 5.963 | 287.705 | −0.480 | 1.194 | 0.047 | 1.227 | 0.556 | 1.174 | −0.467 | 1.224 |

| Household with children | 0.083 | 0.170 | 0.297* | 0.159 | 0.389** | 0.160 | 0.008 | 0.170 | 0.109 | 0.172 |

| Democrat | −0.117 | 0.132 | −0.053 | 0.117 | 0.101 | 0.119 | −0.094 | 0.134 | 0.296** | 0.131 |

| Republican | −0.133 | 0.135 | −0.349*** | 0.120 | −0.157 | 0.122 | −0.202 | 0.137 | 0.101 | 0.132 |

| Phoenix resident | 0.270** | 0.111 | 0.171* | 0.098 | 0.118 | 0.100 | 0.153 | 0.112 | 0.316*** | 0.110 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | −0.140 | 0.382 | 0.235 | 0.362 | −0.347 | 0.371 | 0.044 | 0.409 | 0.349 | 0.401 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 0.363 | 0.355 | 0.362 | 0.344 | −0.422 | 0.352 | 0.102 | 0.385 | −0.114 | 0.371 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | −0.397 | 0.369 | 0.287 | 0.352 | −0.510 | 0.362 | 0.185 | 0.410 | −0.403 | 0.390 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 0.083 | 0.353 | 0.348 | 0.341 | −0.335 | 0.352 | 0.186 | 0.394 | −0.318 | 0.369 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | −0.115 | 0.337 | 0.567* | 0.330 | −0.484 | 0.341 | 0.411 | 0.379 | −0.309 | 0.358 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | −0.044 | 0.365 | 0.253 | 0.347 | −0.412 | 0.358 | −0.095 | 0.401 | −0.465 | 0.379 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | −0.211 | 0.354 | 0.322 | 0.340 | −0.471 | 0.351 | 0.171 | 0.389 | −0.265 | 0.368 |