Abstract

In the initial months of the COVID‐19 outbreak in the United States, people struggled to adjust to the new normal. The burden of managing changes to home and work life seemed to fall disproportionately to women due to the nature of women's employment and gendered societal pressures. We surveyed residents of four western states in the first months of the outbreak to compare the experiences of women and men during this time. We found that women were disproportionately vulnerable to workplace disruptions, negative impacts on daily life, and increased mental load. Women with children and women who lost their jobs were particularly impacted. These results contribute to the growing body of findings about the disproportionate impacts of crises on women and should inform organizational and government policies to help mitigate these impacts and to enhance societal resilience in future emergencies.

Keywords: COVID‐19, equality, pandemic, resilience

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 crisis continues to affect many aspects of life across the world. Starting in March in the United States, most states had stay‐at‐home orders, schools closed, and some workplaces closed while others asked employees to change their work habits and hours drastically. Of course, not everyone's experience of the crisis was the same as it emerged. Specifically, the disproportionate gender impacts of the crisis were immediately noted in the press and among those studying its effects. International, national, and local organizations called for examinations of the “potentially gender‐differentiated impact of the COVID‐19 crisis” (World Bank Group, 2020), noting that economic impacts and household effects might be experienced differently for men and women. In the United States, as stay‐at‐home orders altered daily life and social supports, the gendered impacts of balancing work and family became a particular challenge (Wenham, Smith, & Morgan, 2020). Given the persistent inequity experienced pre‐crisis in most US households, the effects of the changes COVID‐19 brought to daily life in the United States potentially exacerbated existing inequities.

This paper compares the experiences of women and men during the early months of this societal disruption. In this review of literature, we first look at the documented employment impacts of the COVID‐19 outbreak on women's employment. Then, we discuss the unpaid labor added to the already disproportionate load women carry. Building on this literature, six hypotheses about the different experiences of women and men are presented.

2. EMPLOYMENT IMPACTS

Data about US women's employment before the COVID‐19 crisis suggests that women would suffer greater economic repercussions during and after. Despite gains in the workplace, women's employment continues to look different from men's employment due to socially constructed beliefs about sex‐based traits and skills that lead to job typing (i.e., gender essentialism; Moskos, 2019). Women in the United States make up the majority of minimum‐wage, lower‐wage, and part‐time workers (Roy, 2020a; Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020). They make up over 90% of health care, early education, and domestic (HEED) workers and other professions consistent with caregiving (Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020)—professions which typically suffer lower wages (Himmelstein & Venkataramani, 2019). Despite their lower wages, over 70% of US households with children depend on a woman's income (Roy, 2020a). Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women face an even greater gap in wages (Roy, 2020a; Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020). Women are generally in more vulnerable economic positions despite the important role they play in the economic viability of their households.

Data so far suggest that women's employment experiences were significantly impacted as COVID‐19 spread through the United States in 2020. Though past recessions have impacted men's employment significantly, the COVID‐19 crisis disproportionately affected the service occupations that employ women (Alon, Doepke, Olmstead‐Rumsey, & Tertilt, 2020; Durant & Coke‐Hamilton, 2020; He & Torres, 2020). Nearly 60% of jobs lost in the United States by mid‐March were held by women (Institute for Women's Policy Research, 2020), and BIPOC women were hit especially hard by layoffs (He & Torres, 2020). Due to the nature of women's employment, those who are not laid off face difficult decisions. Women make up the majority of those employed in what have become front‐line roles in health care and service (e.g., grocery store clerks) industries (Bahn, Cohen, & van de Meulen Rodger, 2020). Telecommuting is not an option in these front‐line positions (Bahn et al., 2020; Freund & Hamel, 2020); thus, those who remain employed might have to choose between paid employment and staying home to care for children as daycares and schools close (He & Torres, 2020).

3. IMPACTS ON WOMENS'S UNPAID LABOR

The importance of the paid and unpaid care work of women is particularly striking in the face of the COVID‐19 crisis. Women's paid and unpaid caregiving underlies US social and economic systems (Bahn et al., 2020; Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020). Despite the fact that US women are near equal participants in the paid workforce, they continue to perform more than their share of household labor in two‐parent households (Alon et al., 2020). Estimates place the economic value of the “second shift”—the unpaid household responsibilities disproportionately carried by women—(Hochschild & Machung, 1990) at around $40,000 per woman per year on average (Roy, 2020a). That women are uniquely suited to household and caregiving duties and should therefore manage them remains a dominant cultural narrative in the United States. (Hamid Rao, 2019). Neoliberal views of mothers as multitasking individuals who excel in every realm of their lives place additional pressure on women to balance the unexpected and emerging scope of the crisis effortlessly and on their own (Güney‐Frahm, 2020).

COVID‐19 and the subsequent stay‐at‐home recommendations that shut down businesses and schools exacerbated already existing inequity in households and added additional responsibilities. “Shutdowns also create more housework, which women traditionally do more of. Restaurant closures mean more cooking. More time inside means more reasons to clean the house” (He & Torres, 2020). Children needed to complete the school year at home, sick people needed care (World Bank Group, 2020), and previously outsourced household work had to be covered (Bahn et al., 2020)—all tasks that often fell to women. Single mothers have been hit particularly hard (Alon et al., 2020). New responsibilities for many women included managing remote schooling for children, with nearly all women reporting they spent more time helping children complete the school year remotely than their male partners (Carlson et al., 2020). Many women reported that their unequal load of existing household work remained unchanged (Carlson et al., 2020). “COVID‐19 exposes how the usual functioning of the labor market combines with gender roles to require more work from women than from men. Although many of the challenges for women are not unique to this time, COVID‐19 exacerbates their impacts” (Bahn et al., 2020, p. 698).

With any semblance of work–life balance falling away and a “never‐ending shift” becoming the norm (Boncori, 2020), women might be forced into prioritizing unpaid household and care work (Alon et al., 2020) through their own volition (e.g., moving to part‐time work; Durant & Coke‐Hamilton, 2020) or because they are more likely to be laid off (Institute for Women's Policy Research, 2020). Anecdotal (Güney‐Frahm, 2020) and self‐reported evidence (Carlson et al., 2020) show that additional care burdens are being disproportionately placed on women due to COVID‐19. Early on in the pandemic in the United States (e.g., March and April 2020), reliance on gender performativity—the expectation that women are better equipped and socially expected to provide care—seemed to drive many men's and women's reactions and behaviors (Hennekam & Shynko, 2020). Neoliberal policies result in reduced supports for women, who are more likely to be in paid and unpaid caregiver roles. People are experiencing significant stress in their lives, and traditional caregiver roles lead women to absorb others' stress in additional to their own. Indeed, women's experiences have already been different; early data reported more stress and anxiety as they focused on the needs of those around them (Hennekam & Shynko, 2020).

Our study compared the mental load and economic toll of COVID‐19 on men and women in four western, largely rural states. Understanding not only the unequal economic effects of the pandemic but also different mental and social effects on men and women is necessary to effectively and ethically address the impacts of the crisis (e.g., Roy, 2020b; World Bank Group, 2020).

Based on existing inequities and the societal effects of the pandemic on the structures of daily life, we predicted that women would report different impacts in the early days of the crisis.

Hypothesis 1

Women were particularly vulnerable to workplace disruptions owing to the coronavirus pandemic.

Hypothesis 2

Women were more likely to be affected by the coronavirus pandemic in negative ways in their daily lives than were men.

Hypothesis 3

Women were more likely to carry a heavy mental load owing to the coronavirus pandemic than were men.

Hypothesis 4

Women with children were particularly likely to suffer substantial negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

Hypothesis 5

Women subjected to work loss were particularly likely to suffer substantial negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

In addition, we predicted that state policy orientations would affect women's experiences of the pandemic, given that most decisions about measures taken in response to the spread of COVID‐19 were enacted at the state level. Specifically, we expected that states with neoliberal policy orientations that forced responsibilities onto individuals would show more negative impacts on women as efforts to mitigate virus spread took place. In states with more social supports in place for women and families, we thought those structures would assist women in navigating the early impacts of shutdowns.

Hypothesis 6

More neoliberal policy orientations at the state level exacerbated negative impacts of the coronavirus on women as compared to men.

4. METHOD

We collected data for this study via the Western States Coronavirus Survey, an online survey in the field in four US states in April 2020. The primary purpose of the survey was to collect information as the coronavirus pandemic and associated policy actions unfolded. The web‐based questionnaire covered public health items such as worry, disruption, employment consequences, individual mitigation behaviors, and attitudes toward policy actions. See the Appendix S1 for relevant items from the questionnaire. We chose the four states—Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, and Utah—based on regional interest and on diversity in terms of both demographics and policy orientations. At the time, the four states had implemented different approaches to the pandemic. Colorado and Montana had relatively strict stay‐at‐home orders in place. North Dakota had no such order and was relying on individual responsibility as an overall approach. Utah occupied a middle ground, with no formal stay‐at‐home order but a “Stay Safe, Stay Home” directive from the governor instead. Additionally, the four states have rather different orientations toward gender and social policies overall.

Respondents to the survey were recruited from Qualtrics' online probability panel. A total of 2220 individuals responded, with the following breakdown across states: 503 individuals in Colorado (April 10–19); 738 in Montana (April 10–27); 481 in North Dakota (April 10–25); and 498 in Utah (April 10–15). The overall margins of error, which are conservative margins of error based on a 95% confidence level and response distribution of 50%, are: ±4.4 percentage points for Colorado. 3.6 for Montana; 4.5 for North Dakota, and 4.4 for Utah. A screening procedure blocked or removed respondents if they were under the age of 18, were not a resident of one of the four target states, or finished the questionnaire in less than one‐third of the median completion time.

We have applied post hoc analytical weights for purposes of presenting descriptive statistics. Despite recruitment of individuals from a probability panel, certain characteristics were overrepresented or underrepresented among our respondents. Consequently, we have weighted samples using iterative proportional fitting (i.e., raking), which forces sample margins to approximate population margins for key demographic traits (see Battaglia, Hoaglin, & Frankel, 2009). We have raked weights by respondent age, gender, education, race, ethnicity, and urban versus rural residence to match US Census Bureau data for each state. We have also trimmed the weights to prevent overweighting. In what follows, we typically present results as weighed in this manner across the four states in order to best approximate population values.

Our primary statistical method for testing our hypotheses is to apply equality of proportions Z‐tests for independent samples. This method is most appropriate given the proportional form of the data and the separate nature of the subgroups generating these proportions. In other words, we are testing proportions for two separate groups of people rather than testing values for two variables for a single group of people. Further, the proportional nature of the data makes the Z‐test superior to a t‐test.

5. RESULTS

The results of tests for Hypotheses 1–3 appear in Table 1. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, women were generally more vulnerable to workplace disruptions owing to the coronavirus pandemic than were men in statistically significant ways. Women were less likely to be designated as essential workers and were more likely to report being laid off or furloughed and to report losing work income. Furthermore, women were more likely to report that they had filed for unemployment benefits after losing work, suggesting that they were more likely to need assistance to get by (though social norms related to men asking for help may have played a role here, too).

TABLE 1.

Equality of proportions tests for gender disparities in Coronavirus effects

| Female % | Male % | Z‐Score | p ≤ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace effects (H1) | ||||

| Laid off or furloughed | 29.6% | 21.7% | 4.23 | 0.001 |

| Loss of work income | 44.4% | 38.3% | 2.90 | 0.004 |

| Unemployment filing (for eligible) | 62.7% | 45.9% | 3.29 | 0.001 |

| Designated essential worker | 33.9% | 39.1% | −2.19 | 0.029 |

| Daily life effects (H2) | ||||

| Disruption | 80.5% | 72.6% | 4.37 | 0.001 |

| Loss of support services | 34.0% | 22.0% | 6.25 | 0.001 |

| Difficulty obtaining food | 42.0% | 28.9% | 6.40 | 0.001 |

| Inability to pay regular bill | 29.6% | 20.1% | 5.14 | 0.001 |

| Substantial retirement account loss | 34.0% | 41.5% | −3.62 | 0.001 |

| Increased childcare responsibilities | 20.2% | 16.5% | 2.24 | 0.025 |

| Mental load effects (H3) | ||||

| Stress | 67.8% | 50.2% | 8.38 | 0.001 |

| Prepared to deal with infection | 73.5% | 78.1% | −2.51 | 0.012 |

| Worry‐self catch | 49.5% | 38.9% | 4.94 | 0.001 |

| Worry‐self illness | 50.2% | 39.1% | 5.17 | 0.001 |

| Worry‐self death | 41.3% | 30.6% | 5.16 | 0.001 |

| Worry‐self testing | 39.7% | 34.3% | 2.59 | 0.010 |

| Worry other catch | 75.1% | 64.2% | 5.55 | 0.001 |

| Worry other illness | 75.0% | 64.0% | 5.57 | 0.001 |

| Worry other death | 72.7% | 58.8% | 6.86 | 0.001 |

| Worry other testing | 56.7% | 44.6% | 5.66 | 0.001 |

| Worry health care services | 45.1% | 36.3% | 4.19 | 0.001 |

| Worry health care testing | 48.6% | 41.5% | 3.33 | 0.001 |

| Worry health care ventilators | 49.8% | 38.5% | 5.32 | 0.001 |

| Worry health care ICU beds | 49.5% | 37.8% | 5.51 | 0.001 |

| Worry health care prioritization | 48.0% | 36.0% | 5.68 | 0.001 |

| Worry small businesses | 78.4% | 71.1% | 3.94 | 0.001 |

| Worry economic depression | 82.1% | 74.1% | 4.53 | 0.001 |

Note: Depending on the underlying variable, the percentage represents: (1) individuals to whom the event has already happened or to whom the event is expected to happen or (2) respondents indicating a moderate or high degree of the characteristic. The percentages are based on the raked weights. All tests are two tailed. The calculation of Z‐scores is also based on values after applying the raked weights.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that women were more likely to be affected by the coronavirus pandemic in negative ways in their daily lives than were men. Consistent with the hypothesis, women were more likely to report that their lives had been disrupted generally. They were also more likely to report that the pandemic had caused them to lose support services, had led to difficulties obtaining food, had caused them to miss payment on a regular bill, and had increased their childcare responsibilities. The only item inconsistent with the hypothesis was substantial loss in retirement accounts, perhaps because women did not have preexisting savings like men did.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that women were more likely to carry a heavy mental load owing to the coronavirus pandemic than were men. Once again, the results showed substantial support for the hypothesis. Women reported a higher level of stress and a lower level of preparedness than did men. The stress result was particularly striking. The questionnaire also included 16 different items about worry associated with the pandemic. Four of these items dealt with potential health impacts on the respondent personally, four dealt with potential impacts on people the respondents knew, five dealt with potential impacts on the local health care system, and the final two dealt with economic impacts more broadly. Across all 16 worry items, women were more likely to report a moderate or high degree of worry.

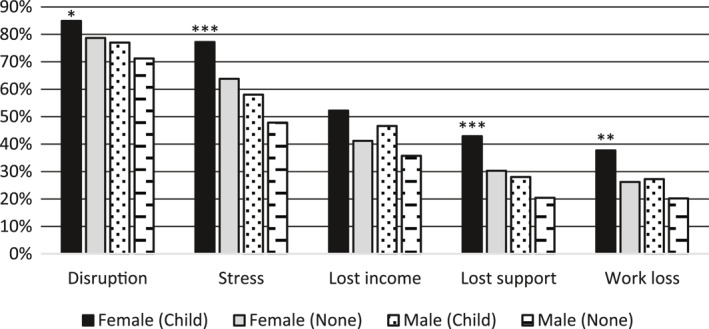

Figure 1 presents the results from testing Hypothesis 4, which proposed that women with children were particularly likely to suffer substantial negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic. The variables used in this figure are a selected subset of those shown in Table 1 chosen based on relevance and representativeness. As shown in the figure, women with children were more likely to suffer substantial negative effects than were the other three subgroups—women without children, men with children, and men without children. When compared against the next highest category, this difference was statistically significant in every instance except for lost income. This pattern holds widely across the variables in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Coronavirus effects by gender & parental status. These results are a test of H4. Equality of proportions statistical tests were performed to compare the female with children category against the next highest category for each impact type (e.g., disruption). The result appears above the “Female (Child)” bar for each impact. ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05

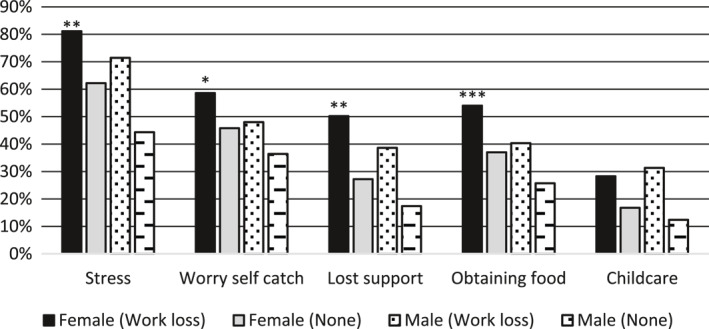

Hypothesis 5 proposed that women subjected to work loss were particularly likely to suffer substantial negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic. The variables shown in Figure 2 are representative of cascading effects that might occur as a result of work loss. Women subjected to work loss were more likely to suffer substantial negative effects than were members of the other three subgroups—women not subjected to work loss, men subjected to work loss, and men not subjected to work loss. The category of men subjected to work loss was the comparison group (i.e., next highest score) in all cases. This suggests that work loss was a primary, driving factor for other negative effects. This pattern held for stress, worry about catching the coronavirus, loss of support services, and difficulty obtaining food. The one case in which the pattern did not hold was increased childcare responsibilities. However, what this analysis does not account for is the prepandemic level of childcare responsibilities (which was likely lower for men) or the propensity for men to over report the volume of their household responsibilities. Again, this pattern holds widely across the variables in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

Coronavirus effects by gender & work loss. These results are a test of H5. Equality of proportions statistical tests were performed to compare the category of women who had experienced or expected work loss against the next highest category for each impact type (e.g., stress). The result appears above the “Female (Work loss)” bar for each impact. ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05

Finally, Hypothesis 6 proposed that more neoliberal policy orientations at the state level exacerbated negative impacts of the coronavirus on women as compared to men. Table 2 provides information designed to gauge each state's neoliberal policy orientation. Greater “freedom,” from a neoliberal perspective, typically also means fewer protections for vulnerable groups and the production of greater inequities. The first metric is women's earnings as a percentage of men's earnings by state, as compiled by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019). The second is a measure of “labor market freedom” as complied by the CATO Institute, (2020). This metric essentially indicates greater labor policy neoliberalism as scores increase. The third is a measure of policy liberalism compiled across 148 different policies (Caughey & Warshaw, 2015, 2016). Liberal policies and neoliberal ones generally run in opposing directions. The conceptualization of liberal policies used here emphasizes “greater government regulation and welfare provision to promote equality and protect collective goods, and less government effort to uphold traditional morality and social order at the expense of personal autonomy” (Caughey & Warshaw, 2016, p. 901). Therefore, higher scores on policy liberalism are indicators of a lesser neoliberal orientation. The rankings across the four states differ slightly from one metric to another, but the same basic pattern emerges. Colorado and Montana are relatively less neoliberal in their policy orientation, while North Dakota and Utah are more neoliberal.

TABLE 2.

State orientation scores

| Women's earnings as % of men's (2018) | Labor market freedom (2016) | Policy liberalism (2014) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorado | 84.9% | −0.031 | 0.175 |

| Montana | 78.6% | −0.025 | 0.267 |

| North Dakota | 73.9% | −0.016 | −1.506 |

| Utah | 71.8% | 0.027 | −1.142 |

Note: The first data column figures come from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, (2019). The second column figures come from the CATO Institute (2020) and are basically a measure of labor policy neoliberalism, with higher scores indicating greater neoliberalism. The final column figures come from Caughey and Warshaw (2016), who look at 148 different policies as indicators of broader policy liberalism.

We assessed the potential influence of neoliberal policies on the coronavirus' impact on women in a few different ways, as shown in Table 3. These are a subset of the same variables used in constructing Table 1. Each cell gives the female‐male difference for a particular state for a particular variable. For example, the first cell tells us that the difference between female reports of being laid off or furloughed (or expecting it to happen) and corresponding male reports is 10.8 percentage points. The underlying values are 30.6% for females and 19.8% for males in Colorado in our data.

TABLE 3.

Gender differences in Coronavirus impacts by state

| Colorado female–male difference | Montana female–male difference | Nor Dakota female–male difference | Utah female–male difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronavirus effects (H6) | ||||

| Laid off or furloughed | 10.8 | 7.0 | 5.7 | 8.6 |

| Loss of work income | 11.1 | 7.6 | −0.7 | 5.5 |

| Unemployment filing (for eligible) | 17.8 | 9.3 | 41.9 | 0.5 |

| Designated essential worker | −4.5 | −7.7 | −1.5 | −5.7 |

| Disruption | 15.7 | −0.1 | 6.1 | 13.9 |

| Loss of support services | 17.5 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 11.5 |

| Increased childcare responsibilities | 4.7 | 8.1 | −3.2 | 3.1 |

| Stress | 22.6 | 18.8 | 15.0 | 12.8 |

Note: Depending on the underlying variable, the separate male and female percentages represent (1) individuals to whom the event has already happened or to whom the event is expected to happen or (2) respondents indicating a moderate or high degree of the characteristic. The values reported in the cells are then the difference between the female percentages and male percentages for each state. The cell values, then, are percentage points.

A basic condition that would need to be met for us to find support for the hypothesis is an ascending order as you go left to right in each row (except for Designated essential worker). That condition is not met. In fact, a more common pattern is for values to descend overall. The data are inconsistent with the hypothesis.

6. DISCUSSION

Our study examined work‐related effects on women as compared to men in four western states early in the coronavirus epidemic in the United States. We found that women were generally more vulnerable to workplace disruptions and were more likely to seek unemployment assistance as a result of these disruptions. Furthermore, we found corresponding effects in women's daily lives, including increased childcare responsibilities, and corresponding effects in the mental load being carried by women across many different types of worries. These negative outcomes often had cascading effects. Women with children and women subjected to work loss were particularly likely to suffer substantial negative effects as compared to other groups. Acknowledging and understanding gender effects should be a first step in informing both public and workplace policies.

Inequalities that existed prior to the pandemic have amplified in the last few months. “Gender inequality begets gender inequality, and this process is only exacerbated in times of crisis or in the face of major shocks such as the outbreak of COVID‐19” (World Bank Group, 2020). Governments and organizations have an opportunity to engage in policy making to reduce chances that this gendered impact will be felt in the future (Freund & Hamel, 2020). Now is the time to ask what should/could be done to improve women's experiences in the workplace and in their homes to mitigate impacts of future pandemics. “The coronavirus pandemic presents us with an opportunity to effect systemic changes that could protect women from bearing the heaviest brunt of shocks like these in the future” (Durant & Coke‐Hamilton, 2020). Now is the time to ask: What policies can we put in place to move beyond merely increasing participation of women in the labor market? How can we make meaningful changes that increase the resilience of society? Cornerstone research on the concept of resilience emphasizes the “fairness of risk and vulnerability to hazards,” the “level and diversity of economic resources,” and the “equity of resource distribution” as key elements of the “networked adaptive capacity” of economic development (Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, & Pfefferbaum, 2008). A great deal of work remains to create equity for women along these lines, and continued inequities threaten the ability of society to resist systemic shocks or to overcome them when overwhelmed. This careful theorizing about resilience also highlights the empowerment of disadvantaged groups as a key element of the networked adaptive capacity of community competence (Norris et al., 2008). The empowerment of women will boost resilience when the next major shock to our economic system and our society comes along.

Contrary to our expectations, at least early in the coronavirus pandemic, more neoliberal policy orientations in states did not exacerbate the negative influences on women as compared to men. The results might partially be a function of preexisting female labor participation rates in these states. For example, Utah's rate of 69.8% (US Department of Labor, 2020) was somewhat lower than those for the other states. This means that variables like job loss had less room to move initially. Regardless, the “normative individualism” of “neoliberalism serves…to justify the state's retreat from social service provision” (Güney‐Frahm, 2020, p. 847). Policies supporting women support families and more equal family arrangements—the kind most Americans favor (Hamid Rao, 2019). Increasing social services that reduce caregiving burdens on women (Durant & Coke‐Hamilton, 2020); providing paid family leave (Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020), universal health care (Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020), flexible work arrangements (Durant & Coke‐Hamilton, 2020); and practicing gender budgeting—which recognizes the impact of gender (Roy, 2020b)—are some of the necessary policies to promote equality. These policies could be put into practice through organizations or through local, state, or national legislation.

These findings are somewhat limited by the timing of the data collection and the close‐ended nature of the questionnaire. Without question, some people's experiences have changed across the intervening months since the survey went out in April. For example, we might see differences based on neoliberal policy orientations as the crisis has continued. The timing likely affected our results, but acknowledging the context of the data collection could inform more nuanced responses. This study provides a snapshot of the initial stages of a pandemic. General knowledge of people's experiences in the early weeks can inform policies that can mitigate those impacts for future crises. Hopefully, these early results can be compared to effects at later points in this extended crisis; the quantitative nature of the data lends itself well to future comparisons. Both initial impacts and continued experiences are necessary for understanding and change. These data complement the work of others to expand our understanding of people's experiences and reactions to the pandemic and its impacts on our lives.

National legislation for COVID‐19 relief has recognized these differential impacts and included paid leave—a first for national legislation (Bahn et al., 2020). Efforts to support those doing the critical work of caregiving are present in multiple levels of relief legislation (Thomason & Macias‐Alonso, 2020). Though this legislation was a good start and set a promising precedent to address care responsibilities, many people were not eligible, and the support is not long term. Recognizing that caregiving work is vital to our society and is often underpaid or uncompensated could be an outcome of the pandemic. Advocating for such changes at all levels will improve the workplace for all of us. “Our ability to bounce back from this crisis is dependent on how we include everyone equally. If more women take part in shaping a new social and economic order, chances are that it will be more responsive to everyone's needs and make us all more resilient to future shocks” (Durant & Coke‐Hamilton, 2020). We can choose not to continue reinforcing inequities as we emerge from the pandemic. As a society, a focus on gender equity to inform decisions about workplaces and communities should shape the “new normal” that emerges.

Supporting information

Supporting Information 1docx

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this project came from the Office of Research, Economic Development and Graduate Education at Montana State University‐Bozeman, the Department of Political Science at Montana State University‐Bozeman, and the Center on American Politics at the University of Denver. The views expressed in this research are those of the investigators and do not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.

Biographies

Dr. Amber N. W. Raile is an associate professor of management in the Jake Jabs College of Business & Entrepreneurship at Montana State University ‐ Bozeman. Her research examines the role of communication in creating positive organizational environments and examining multi‐level social change related to defining, measuring, and securing political will and public will across contexts. She is particularly interested in women's experiences and efforts to reduce inequities.

Dr. Eric D. Raile is an associate professor of political science and the director of the Human Ecology Learning and Problem Solving Lab at Montana State University – Bozeman. His areas of specialization are public policy and comparative politics. His research largely focuses on governance and accountability issues, particularly as they relate to the environment, food systems, and health care.

Dr. David C.W. Parker is professor and head of political science at Montana State University – Bozeman. He is a student of legislatures, primarily focused on legislative oversight and representational relationships in the U.S. Congress, the House of Commons, and the Scottish Parliament. His new book project will look at how newly elected members of the 2019 House of Commons intake adapt their representational and governing styles to a changing British electorate.

Dr. Elizabeth A. Shanahan is a professor of political science at Montana State University‐Bozeman. Through application of the Narrative Policy Framework, her research primarily investigates the power of policy narratives in shaping governmental and individual decisions. Much of her work is interdisciplinary and focuses on dynamics within human systems and their interactions with ecological systems.

Dr. Pavielle Haines is an assistant professor of political science at Rollins College. Her research focuses on identity politics, race, campaigns, public opinion, and political psychology. Her book manuscript explores how conservative presidential candidates use patriotic rhetoric to influence voters by promulgating an exclusionary and racially hostile version of American identity. She received her PhD from Princeton University in 2018.

Raile, A. N. W. , Raile, E. D. , Parker, D. C. W. , Shanahan, E. A. , & Haines, P. (2021). Women and the weight of a pandemic: A survey of four Western US states early in the Coronavirus outbreak. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S2), 554–565. 10.1111/gwao.12590

REFERENCES

- Alon, T. M. , Doepke, M. , Olmstead‐Rumsey, J. , & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 on gender equality. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w26947 [Google Scholar]

- Bahn, K. , Cohen, J. , & van de Meulen Rodger, Y. (2020). A feminist perspective on COVID‐19 and the value of care work globally. Gender, Work & Organization, 27, 695–699. 10.1111/gwao.12459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, M. P. , Hoaglin, D. C. , & Frankel, M. R. (2009). Practical considerations in raking survey data. Survey Practice, 2(5). 10.29115/SP-2009-0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boncori, I. (2020). The never‐ending shift: A feminist reflection on living and organizing academic lives during the coronavirus pandemic. Gender, Work & Organization, 27, 677–682. 10.1111/gwao.12451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D. L. , Petts, R. , & Peppin, J. R. (2020). US couples’ divisions of housework and childcare during COVID‐19 pandemic. SocArXiv. Retrieved from https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/jy8fn [Google Scholar]

- CATO Institute . (2020). Freedom in the 50 states: Labor. Retrieved from https://www.freedominthe50states.org/labor [Google Scholar]

- Caughey, D. , & Warshaw, C. (2015). Replication data for: The dynamics of state policy liberalism, 1936‐2014 [Data set]. Harvard Dataverse. 10.7910/DVN/ZXZMJB [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey, D. , & Warshaw, C. (2016). The dynamics of state policy liberalism, 1936‐2014. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 899–913. 10.1111/ajps.12219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durant, I. , & Coke‐Hamilton, P. (2020). COVID‐19 requires gender‐equal responses to save economies. United National Conference on Trade and Development. https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2319 [Google Scholar]

- Freund, C. , & Hamel, I. (2020, May 13). COVID is hurting women economically, but governments have the tools to offset the pain. World Bank Private Sector Development Blog. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/covid-hurting-women-economically-governments-have-tools-offset-pain [Google Scholar]

- Güney‐Frahm, I. (2020). Neoliberal motherhood during the pandemic: Some reflections. Gender, Work & Organization, 27, 847–856. 10.1111/gwao.12485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid Rao, A. (2019, May 12). Even breadwinning wives don't get equality at home. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2019/05/breadwinning-wives-gender-inequality/589237/ [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam, S. , & Shynko, Y. (2020). Coping with the COVID‐19 crisis: Force majeure and gender performativity. Gender, Work & Organization, 27, 788–803. 10.1111/gwao.12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, E. , & Torres, N. (2020). Women are bearing the brunt of the Covid‐19 economic pain. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-opinion-coronavirus-gender-economic-impact-job-numbers/ [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein, K. E. , & Venkataramani, A. S. (2019). Economic vulnerability among us female health care workers: Potential impact of a $15‐per‐hour minimum wage. American Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 198–205. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, A. , & Machung, A. (1990). The second shift. New York, NY: Avon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Women's Policy Research . (2020). Women lost more jobs than men in almost all sectors of the economy. Retrieved from https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/QF-Jobs-Day-April-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Moskos, M. (2019). Why is the gender revolution uneven and stalled? Gender essentialism and men's movement into ‘women's work’. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(4), 1–18. 10.1111/gwao.12406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F. H. , Stevens, S. P. , Pfefferbaum, B. , Wyche, K. F. , & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, K. (2020a). Why women will be hardest hit by a coronavirus‐driven recession. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/90479204/why-women-will-be-hardest-hit-by-a-coronavirus-driven-recession [Google Scholar]

- Roy, K. (2020b). Here's how to achieve gender equality after the pandemic. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/how-to-achieve-gender-equality-after-pandemic/ [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, B. , & Macias‐Alonso, I. (2020). COVID‐19 and raising the value of care. Gender, Work & Organization, 27, 705–708. 10.1111/gwao.12461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . (2019). Highlights of women's earnings in 2018 (Report 1083). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2018/pdf/home.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor . (2020). Labor force participation rate by sex, state and county. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/data/labor-force-participation-rate-by-sex [Google Scholar]

- Wenham, C. , Smith, J. , & Morgan, R. (2020). COVID‐19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Gender and COVID‐19 Working Group. Retrieved from 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group . (2020, April 16). Gender dimensions of the COVID‐19 pandemic [Policy note]. Retrieved from http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/618731587147227244/pdf/Gender-Dimensions-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information 1docx