Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review evaluates current recommendations for pain management in CKD and ESKD with a specific focus on evidence for opioid analgesia, including the partial agonist, buprenorphine.

Recent Findings

Recent evidence supports the use of physical activity and other nonpharmacologic therapies, either alone or with pharmacological therapies, for pain management. Nonopioid analgesics, including acetaminophen, topical analgesics, gabapentinoids, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants may be considered based on pain etiology and type, with careful dose considerations in kidney disease. NSAIDs may be used in CKD and ESKD for short durations with careful monitoring. Opioid use should be minimized and reserved for patients who have failed other therapies. Opioids have been associated with increased adverse events in this population, and thus should be used cautiously after risk/benefit discussion with the patient. Opioids that are safer to use in kidney disease include oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, methadone and buprenorphine. Buprenorphine appears to be a promising and safer option due to its partial agonism at the mu opioid receptor.

Summary

Pain is poorly managed in patients with kidney disease. Non-pharmacological and non-opioid analgesics should be first-line approaches for pain management. Opioid use should be minimized with careful monitoring and dose adjustment.

Keywords: End-stage kidney disease, chronic kidney disease, pain, opioids, buprenorphine

Introduction

Chronic pain is a common symptom experienced by patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [1,2]. Untreated pain in this population negatively impacts health related quality of life (HRQOL), dialysis adherence, healthcare utilization and mortality [3-5]; and may contribute to other physical and psychosocial symptoms such as depression, anxiety and fatigue [6].

There is a disproportionately high use of opioids in this population due to limited availability of non-pharmacological treatment options or safe non-opioid pharmacological options. In a study of over 400,000 ESKD patients, over half had received an opioid prescription, 3.2 times the rate in the US population [7] and 20% were on long term opioid therapy (LTOT) [8]. Chronic opioid use in patients with kidney disease has been associated with increased risk of altered mental status, falls, fractures, hospitalizations and mortality, in a dose-dependent manner [9-12]. However, closely-monitored LTOT may be warranted in some patients who fail to respond to other pain treatments. This requires careful consideration of risks and benefits.

Pain management in kidney disease is a top research priority, and is being fostered in the nephrology community by enterprises such as the Kidney Health Initiative, a public-private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology and US Food and Drug Administration [13,14]. Additionally, the recently established Hemodialysis Opioid Prescription Effort (HOPE) Consortium, funded by the National Institutes of Health’s Helping to End Addiction Long term mission and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney diseases (NIDDK), will address pain management and opioid safety in this population [15].

The goal of the current review is to provide practical guidance for treating pain, summarize evidence on non-pharmacological and pharmacological options for pain, and focus on safety and efficacy of medications including opioids.

Approach to Pain Management

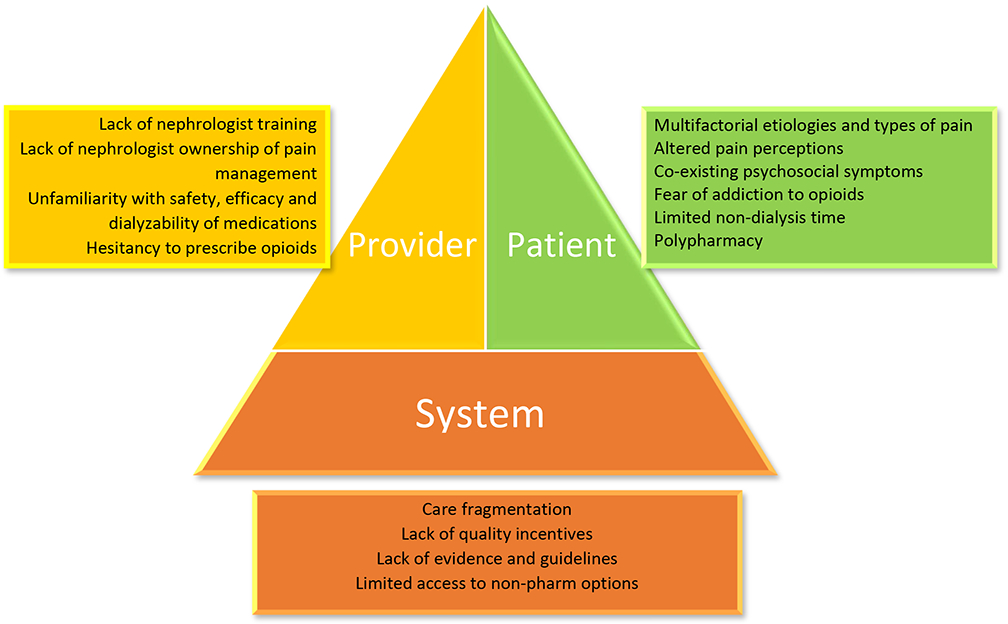

Multiple patient, provider, and healthcare-system factors make pain management challenging in this population (Figure 1) [16]. The multifactorial etiologioes of pain and common comorbid conditions in patients with kidney disease result in varying types of pain (neuropathic, nociceptive, or both). [17-21]. Provider- and system-related factors relate to lack of training for nephrologists in treating pain, fragmentation of care and most importantly lack of scientific evidence and guidelines around pain management in CKD and ESKD [22,23].

Fig 1.

Challenges in pain management in patients with kidney disease

Pain assessment

This should start with assessment of a) pain severity using various standardized tools, most common of which is the numerical rating scale [24]; b) pathophysiologic evaluation into mechanism of injury and type of pain; c) psychosocial evaluation of co-occurring factors that contribute to pain or make treatment of pain more challenging, such as depression, anxiety, and a history of substance use disorder [25]; and d) overall impact of pain using tools such as the PEG, a validated, three-item tool assessing Pain intensity, interferences with Enjoyment in life, and General activity [26].

Prior to initiating treatment, discussions should include realistic expectations for improvements in pain and function, which can strengthen the therapeutic alliance between patient and provider [27]. When patients’ anticipated pain relief does not align with their experience it requires calibration of expectations [28].

Non-pharmacologic approaches

Non-pharmacologic options range from psychosocial or behavioral based interventions (e.g.: cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT], acceptance and commitment therapy, relaxation, music therapy, mindfulness) to physically-oriented interventions (e.g.: exercise, physical therapy, yoga, acupuncture, electrical stimulation). Psychosocial interventions are supported by robust evidence from the general population as effective approaches for reducing pain severity, interference, pain-related disability and psychological distress, and have limited but promising evidence for reduction in opioid use, and even opioid misuse behaviors [29-35]. Currently, such evidence in kidney disease is very limited and of poor quality [36-39]. Two NIDDK-funded trials (Technology Assisted Collaborative Care and the HOPE Consortium trial [15]) are currently testing telemedicine-delivered CBT-based interventions for pain in patients receiving hemodialysis [40]. Physical therapy or exercise-based interventions have been successful in improving pain in the general population [41]. Few studies of exercise, physical therapy, yoga, or acupuncture in patients with kidney disease have included pain as an outcome but show promising results [42-45]. Given that non-pharmacological interventions are generally safe, further research should test the effectiveness, feasibility and acceptability of them for patients with kidney disease.

Pharmacological approaches

Review the available evidence on pharmacokinetic, efficacy, and safety profiles of analgesics in patients with kidney disease is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Summary of dose recommendations are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Recommended non-opioid medications in patients with kidney disease

| Medication | Metabolism and PK comments | Dosing in CKD | Dosing in ESKD | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medications for nociceptive pain | ||||

| Acetaminophen | Hepatic, excreted in the urine primarily as non-toxic metabolites High oral bioavailability 85-98% Median onset 11 minutes and median duration of action ~ 4 hours after 1000 mg oral dose [83] |

ClCr 10-50 mL/min: 650 mg q 6h prn Max daily dose 4000 mg |

ClCr < 10 mL/min or dialysis: 650 mg q 8h prn Max daily dose 4000 mg [84] |

Use scheduled doses instead of as needed for continuous pain control Use with caution and Lower max daily dose (2000 mg) if liver disease or daily alcohol |

| NSAIDs, preferably COX-2 selective agents such as celecoxib | Reduce dose and increase dosing interval, use for short term (</= 5 days only) Contraindicated in CKD stage 5 |

No dose adjustment, use for short term only | Monitor for volume retention, cardiotoxicity, renal and gastrointestinal toxicity | |

| Topical analgesics (NSAIDs, lidocaine, capsaicin) | Systemic exposure with topical NSAIDs is 2-3% than with oral, but increases with higher dose applied to larger surface area [85] | Avoid high dose topical NSAID use over large surface area | ||

| Medications for neuropathic pain | ||||

| Pregabalin | Negligible, 90% excreted renally as unchanged drug High oral bioavailability ≥ 90% Onset of pain relief ~ 1 week |

Max daily dose: ClCr 30-60 mL/min: 300 mg daily (2-3 divided doses) ClCr 15 to 30 mL/min: 150 mg daily (1-2 divided doses) ClCr < 15 mL/min: 75 mg daily (single dose) |

Start at 25 mg once daily, Maximum dose 75 mg once daily Well dialyzed, Dose post-HD |

Start at low dose and uptitrate every 1-2 weeks, monitor for altered mental status and falls |

| Gabapentin | Not metabolized, excreted renally as unchanged drug Bioavailability is dose dependent: is upto 80% with 300mg/d but decreases as dose increases to <50% above 1200 mg/d |

Max daily dose: ClCr 50-79 mL/min: 1800 mg daily (3 divided doses) ClCr 30-49 mL/min: 900 mg/day (2-3 divided doses) ClCr 15-29 mL/min: 600 mg/day (1-2 divided doses) ClCr < 15 mL/min: 300 mg/day (single dose) |

Maximum dose 300 mg once daily Well dialyzed, Dose post-HD |

Start at low dose and uptitrate every 1-2 weeks, monitor for altered mental status and falls |

| Duloxetine | Extensively metabolized in the liver via CYP1A2 and 2D6 to inactive metabolites, Oral bioavailability 30-80%, >90% protein bound Excretion: renal 70%, fecal 20% |

Start with 20 mg daily Max daily dose: 60 mg ClCr 30-80 mL/min: no dose adjustment necessary ClCr < 30 mL/min: avoid use |

Avoid use (limited data) | Monitor for hyponatremia, can rarely cause serotonin syndrome |

| Venlafaxine | Hepatically metabolized via CYP2D6 to active metabolite, O-desmethylvenlafaxine. Bioavailability is ~ 13% for immediate release and 45% for extended release, primarily excreted renally | Extended release: Start at 37.5 mg once daily Max daily dose: ClCr 30-89 mL/min: 150 mg daily ClCr <30 mL/minute: 112.5 mg daily |

Extended release: Start at 37.5 mg once daily Max daily dose: 112.5 mg daily Poorly dialyzed |

Monitor for hyponatremia, can rarely cause serotonin syndrome |

| Desvenlafaxine (active metabolite of venlafaxine) | Hepatically metabolized Oral bioavailability approximately 80%. Excreted renally approximately 45% as unchanged drug and 24% as metabolites |

Max daily dose: ClCr 30-50 mL/min: 50 mg once daily ClCr <30 mL/min: 25 mg once daily or 50 mg every other day |

Max daily dose: 25 mg once daily or 50 mg every other day. Poorly dialyzed |

Monitor for hyponatremia, can rarely cause serotonin syndrome |

| Amitriptyline | Hepatically metabolized to nortriptyline (active metabolite) Oral doses are completely and rapidly absorbed, > 90% protein bound. Excreted renally as metabolites, 18% as unchanged drug. |

Start at 10 mg once daily at bedtime, No dose adjustment recommended Maximum dose 150 mg daily. |

Start at 10 mg once daily at bedtime, No dose adjustment recommended Maximum dose 150 mg daily. Poorly dialyzed |

Limited evidence in CKD The Beers Criteria recommends avoidance in older adults (strong anticholinergic properties, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention) |

Table 2.

Recommended opioid medications in patients with kidney disease

| Medication | Metabolism and PK comments | Dosing in CKD | Dosing in ESRD | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxycodone (short-acting) | Hepatically metabolized via mainly CYP3A4 to noroxycodone (weakly active) and some by CYP2D6 to oxymorphone (strongly active), High oral bioavailability of 50-87% , t1/2 prolonged to ~ 7 hours in ESKD [86] | Start at 2.5-5 mg every 12 hours, Recommend prolonged dosing interval in severe renal impairment | Start at 2.5-5 mg every 12 hours, Recommend prolonged dosing interval in ESKD Poorly dialyzed |

Caution should be used with long acting formulations and when used concurrently with medications that affect CYP3A4 or CYP2D6 metabolism. [87] |

| Hydromorphone | Hepatically metabolized, Oral bioavailability is Low to moderate | Start at 2.5-5 mg every 6-8 hours | Start at 2.5-5 mg every 6-8 hours, well dialyzed but no supplemental dose required post HD | Use caution with high doses |

| Fentanyl (transdermal) | Hepatically metabolized, 10-20% excreted renally, low oral bioavailability | Dose equivalent dose of patient’s oral narcotics, wean oral opioids after 1-2 days | Dose equivalent dose of patient’s oral narcotics, wean oral opioids after 1-2 days Poorly dialyzed |

Do not start in opioid naïve patient |

| Methadone | Hepatically metabolized to inactive metabolites, >80% oral bioavailability | Start 1-2 mg once or twice a day | Start 1-2 mg once or twice a day Poorly dialyzed |

Do not start in opioid naïve patient. Obtain a baseline EKG and a follow-up EKF 2-4 weeks after starting to monitor for prolonged QT interval. Monitor and correct electrolyte abnormalities |

| Buprenorphine | Hepatically metabolized to B3G (inactive) and norbuprenorphine (active but does not cross blood brain barrier), low oral bioavailability but effective as sublingual or transdermal formulation, excreted mostly fecally (bile) | See Table 3 | See Table 3 Poorly dialyzed |

Do not start in opioid naïve patient. Lesser risk of overdose and respiratory and CNS depression as compared to other opioids |

Non-opioid therapy for nociceptive pain

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen, a common over-the-counter analgesic, and can be tried as scheduled doses for mild to moderate pain, although a Cochrane review found that efficacy in the general population may be limited [88]. It requires no dose adjustment and is generally safe in kidney disease, although may rarely cause analgesic nephropathy with long term use [89].

NSAIDs

Potential risks of NSAIDs include gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal adverse events [90]. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis by interfering with the cyclo-oxygenase pathway, which may increase risk of acute kidney injury, sodium retention, hypertension, hyperkalemia, and heart failure. They may also increase cardiovascular events via vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation [91]. Gastrointestinal and bleeding risks are lower with COX-2 selective agents such as celecoxib [92,93]. Recent epidemiological evidence suggests association of chronic NSAID use with increased risk of CKD progression and hospitalization in patients with CKD, albeit less than that with opioid use [12]. Similarly, in ESKD, NSAID use has been associated with increased mortality, but these findings are confounded by limitations of observational data [63].

Most of these adverse effects are rare, related to cumulative dose and likely modified by an individual’s underlying risk factors, such as comorbidities and concomitant medications. Thus, short-term, cautious use of NSAIDs with consideration of individual risk factors, careful side effect monitoring, and risk/benefit discussion may be appropriate [95]. We agree with recommendations outlined by in a recent review that suggests short-acting NSAIDs could be used short-term (</= 5 days) in patients with CKD Stages 1-3; judiciously in patients with CKD Stage 4; and avoided in CKD 5 [96]. A similar case can be made for cautious use of NSAIDs in ESKD patients, in whom gastrointestinal toxicity and loss of residual renal function are the most concerning side effects. In anuric ESKD patients, there is no effect on glomerular blood flow or tubular function, thus NSAID-mediated electrolyte disturbances, volume retention, and hypertension are of less concern [60].

Topical agents

Topical agents (e.g.: topical NSAIDs, lidocaine patch, high dose capsaicin patch) may provide localized pain relief [97-100]. Topical NSAIDs are efficacious in both acute and chronic pain, have minimal systemic exposure (2-3% of oral dose), and are safe in patients with kidney disease when used over limited surface area [101].

Skeletal muscle relaxants

Skeletal muscle relaxants such as baclofen, methocarbamol, and tizanidine, do not have a role in chronic pain conditions and are only recommended for short-term use in some acute pain conditions such as spasticity and spasms [102]. All skeletal muscle relaxants may cause significant sedation, muscle weakness and dizziness and should be avoided in advanced CKD and ESKD. For example baclofen, which is renally cleared, can cause severe neurotoxicity and muscle paralysis in advanced CKD and ESKD, and should be avoided.

Cannabis

While cannabis may improve some painful conditions, it has not been tested in persons with kidney disease, and its role and safety in this population is unclear [103-105].

Non-opioid therapy for neuropathic pain

In the general population, evidence supports the use of gabapentinoids (pregabalin and gabapentin), tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) as first-line treatments for neuropathic pain.[99] The clearance of both gabapentin and pregabalin decreases and half-life (t½) increases proportionately with worsening renal function, requiring renal dose adjustment (Tables 1 and Supplementary Table 1) [106-108]. Both medications should be dosed post-HD. These agents have been associated with increased risk of altered mental status, falls, and fractures in ESKD patients [109], and concomitant use with opioids is associated with increased hospitalization and mortality [110]. They have been associated with potential misuse and addiction and should be used with caution and close monitoring [111].

Little evidence exists regarding use of TCAs and SNRIs for patients with kidney disease (Tables 1 and 3). TCAs are associated with dose-related anticholinergic and antihistaminic side effects; SNRIs are generally better tolerated. Both of these classes may cause or exacerbate syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. The use of the SNRI duloxetine in patients with ClCr < 30 mL/minute or on dialysis is not recommended by current FDA guidance; however, guidelines from the European Union and Canada suggest its use in severe CKD and ESKD with lower starting doses and cautious monitoring [112].

Table 3.

Comparison of Commonly Prescribed Buprenorphine Products

| Trade Name | Generic Name | Route | FDA Indication | X-Waiver Required? | Starting Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butransa | Buprenorphine | Transdermal patch | Chronic pain | No | 5ug/hr week |

| Belbucab | Buprenorphine | Buccal tablet | Chronic pain | No | 75ug once daily |

| Suboxonec | Buprenorphine-naloxone# | Sublingual film or tablet | Opioid use disorder | Yes* | 2mg-0.5mg |

| Subutexc | Buprenorphine | Sublingual tablet | Opioid use disorder in patients who cannot tolerate naloxone | Yes | 2mg |

Purdue Pharma L.P., Stamford, CT, USA

BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc, Raleigh, NC, USA

Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Incorporation, Richmond, VA, USA

When taken sublingually, the effect of buprenorphine predominates; if injected however, the effect of naloxone predominates.

No X-waiver needed if used off-label for treatment of pain [125]

Opioid therapy for pain

Although the main indication for opioids is for nociceptive pain, they have also been shown to be effective in improving neuropathic pain, especially diabetic neuropathy, either alone or as adjuvants to gabapentinoids [113,114]. The decision to initiate LTOT should be made through a careful risk-benefit evaluation and shared decision-making. Opioids should be avoided if other options are effective, and should be used sparingly at the minimum effective doses. We recommend a similar approach to the CDC guidelines, including maximizing nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid analgesia, establishing clear therapeutic goals, initiating treatment with immediate-release opioids rather than long-acting, starting with low doses, and uptitrating gradually with close monitoring of side effects [8].

The benefits of treatment may include improved quality of life and better functioning. This should be balanced with the increased risks of opioids in kidney disease such as altered mental status, falls, fractures, hospitalizations, and mortality, which occurs in a dose-dependent manner and can be seen even at lower doses [9-12]. These risks may be more pronounced in the older adults, and those with concomitant sedating medications such as gabapentinoids and benzodiazepines [110,115]. LTOT can also have additional adverse effects such as hyperalgesia, sedation, overdose, and progression to opioid use disorder (OUD). An evidence-based tool to help evaluate risk of opioid misuse before initiating treatment is the Revised Opioid Risk Tool, which creates a risk category based on personal and family history of substance misuse, age, and psychological disease [116]. If OUD is suspected, we recommend referral to an addiction treatment provider.

Monitoring of long-term opioid therapy

A cornerstone of LTOT is ensuring proper monitoring. CDC guidelines recommend checking state-wide prescription drug monitoring programs to identify controlled medications prescribed by other providers [8]. Additionally, periodic drug screens are important to ensure prescribed medication use and evaluate for illicit substance use. Urine drug testing is the preferred method of screening due to high sensitivity and specificity [117]. However, this may be challenging in patients with ESKD who produce little or no urine. Oral buccal swabs or saliva testing offer a reasonable alternative but may have logistic issues with specimen collection as these patients frequently have xerostomia.

Specific opioid medications

The pharmacokinetic evidence of commonly used opioid medications in patients with kidney disease is summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Opioids that are safer to use in kidney disease include oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, methadone and buprenorphine. Oxycodone is one of the most commonly prescribed opioids for kidney disease patients in the US [9]. It has predominantly hepatic elimination and is poorly dialyzed (Table 2). Caution should be used with long-acting formulations and when prescribed concurrently with medications that affect CYP3A4 or CYP2D6 metabolism [118]. Similarly, hydromorphone has a reasonable safety profile in kidney disease at lower doses and is dialyzed by HD, but supplemental doses are usually not needed post-HD. Fentanyl appears to be safe in kidney disease, although evidence is limited. On the other hand, morphine and hydrocodone have high risk of accumulation and systemic exposure, thus are contraindicated in patients with CKD or ESKD.

Tramadol is an atypical, centrally-acting opioid with dual action as a weak mu-opioid receptor agonist and SNRI. Tramadol and its active M1 metabolite are renally excreted. Its metabolism can vary unpredictably depending on an individual’s cytochrome P450 genetic profile [119]. Tramadol also has multiple drug interactions that may result in serotonin syndrome or seizures. Thus, we recommend it be used with extreme caution and at reduced doses, but preferably avoided.

Special Consideration: Buprenorphine and Methadone

Less commonly used opioid medications for pain are methadone (full agonist at mu-opioid receptor) and buprenorphine (partial agonist). They are more commonly used for the treatment of OUD where they reduce cravings, abate withdrawal symptoms, and prevent overdose. However, there are formulations for methadone and buprenorphine that can be used to treat chronic pain, as discussed below.

Methadone

Methadone functions as an NMDA-receptor antagonist, giving it additional efficacy for neuropathic pain. The analgesic half-life is 6-8 hours, requiring multiple daily doses. Methadone and its metabolites do not accumulate in CKD or ESKD, thus no dose adjustment is needed and it is not dialyzed out by HD (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Because it can prolong the QTc interval, the electrolyte abnormalities such as hypo/hyperkalemia or hypo/hypermagnesemia that are frequently present in kidney disease may exacerbate its arrhythmia potential.

For patients without OUD, methadone as an analgesic can be prescribed by any provider with an active Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) license, does not require patients to attend a clinic with an Opioid Treatment Program license, and can be legally filled at commercial pharmacies. In contrast, for patients with OUD, methadone is highly regulated, must be dispensed from a federally licensed Opioid Treatment Program, is dosed once a day, and initially requires patients to travel daily to receive observed dosing.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is an efficacious treatment of pain in the general population [120]. Due to its partial agonism, it has a “ceiling effect” which reduces the risks of respiratory sedation and overdose. It is metabolized in the bile duct, requires no dose adjustment in CKD, and is not dialyzed (Table 2). Given its better safety profile compared to full opioids and steady state in CKD/ESKD, it may provide a therapeutic advantage and a safer alternative for pain management in patients with kidney disease who have a physiologic dependence to opioids [121-123].

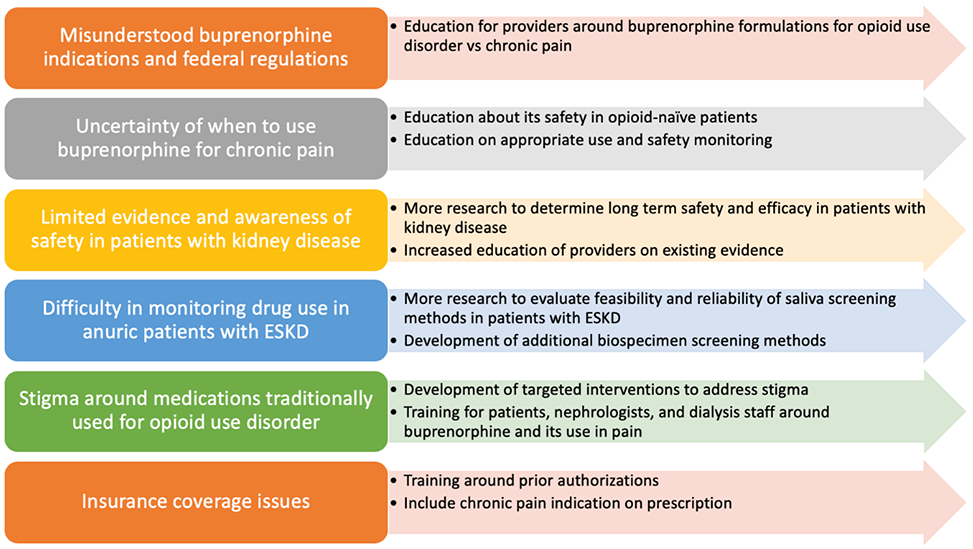

Buprenorphine prescribing for chronic pain remains low due to barriers depicted in Figure 2; potential solutions are offered. Barriers include provider confusion about available buprenorphine formulations, their indications, and federal regulations for X-waiver (Table 3) [124]. Notably, although sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone can be prescribed off-label as an analgesic, several logistical hurdles make that difficult, including requiring documentation of indication [125]. Insurance authorization may also be required for transdermal or buccal formulations of buprenorphine [126,127]. Lastly, given its traditional use as a treatment for OUD, buprenorphine may be stigmatized by patients and providers, similar to methadone [128]. The ongoing HOPE Consortium trial will provide valuable insight into the acceptability, tolerability and efficacy of buprenorphine in patients on dialysis.

Fig 2.

Barriers and potential solutions for increasing use of buprenorphine for chronic pain in patients with kidney disease

Conclusion

Pain is highly prevalent and challenging to treat among patients with kidney disease. Pain management requires careful assessment, continuous monitoring, and shared decision-making of risks and benefits of different pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic options with patients. Long-term therapy with full agonist opioid treatment is associated with significantly higher adverse effects in this population, thus more research into safer alternatives such as buprenorphine is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Pain management in patients with kidney disease is challenging due to multiple patient, provider, and structural factors.

Nonpharmacologic management of pain includes behavioral-based and physically-oriented interventions.

Preferred nonopioid analgesia in CKD and ESKD include acetaminophen, topical analgesics, gabapentinoids, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Before starting opioids, providers should have risk/benefit discussions regarding opioid analgesia, including complete psychosocial assessment and regular monitoring for benefits and adverse effects with evidence-based tools and urine or oral drug screening.

Preferred opioid analgesics include oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, methadone, and buprenorphine.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship: This work is supported by NIH R01 DK114085 (Jhamb), NIH U01 DK123812A (Jhamb and Liebschutz), and NIH U01 DK123813 (Dember).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Laura M. Dember receives compensation for her role as Deputy Editor of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases and consulting fees from Merck.

Conflicts of interest: Laura M. Dember receives compensation for her role as Deputy Editor of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases and consulting fees from Merck.

References

- 1.Mercadante S, Ferrantelli A, Tortorici C, et al. Incidence of Chronic Pain in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease on Dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 2005. October;30(4):302–4. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885392405004343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison SN. Clinical Pharmacology Considerations in Pain Management in Patients with Advanced Kidney Failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2019;14(6):917–31. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30833302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison SN, Jhangri GS. Impact of Pain and Symptom Burden on the Health-Related Quality of Life of Hemodialysis Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 2010. March;39(3):477–85. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885392410000898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris TJ, Nazir R, Khetpal P, et al. Pain, sleep disturbance and survival in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2012. February 1;27(2):758–65. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/ndt/gfr355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisbord SD, Mor MK, Sevick MA, et al. Associations of Depressive Symptoms and Pain with Dialysis Adherence, Health Resource Utilization, and Mortality in Patients Receiving Chronic Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2014. September 5;9(9):1594–602. Available from: http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2215/CJN.00220114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhamb M, Abdel-Kader K, Yabes J, et al. Comparison of Fatigue, Pain, and Depression in Patients With Advanced Kidney Disease and Cancer—Symptom Burden and Clusters. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 2019. March;57(3):566–575.e3. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885392418311205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daubresse M, Alexander GC, Crews DC, et al. Trends in Opioid Prescribing Among Hemodialysis Patients, 2007-2014. Am J Nephrol [Internet]. 2019;49(1):20–31. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30544114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. JAMA [Internet]. 2016. April 19;315(15):1624 Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimmel PL, Fwu C-W, Abbott KC, et al. Opioid Prescription, Morbidity, and Mortality in United States Dialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2017. December 1;28(12):3658 LP–3670. Available from: http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/28/12/3658.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishida JH, McCulloch CE, Steinman MA, et al. Opioid Analgesics and Adverse Outcomes among Hemodialysis Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2018. May 7;13(5):746–53. Available from: http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2215/CJN.09910917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vangala C, Niu J, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Hip Fracture Risk among Hemodialysis-Dependent Patients Prescribed Opioids and Gabapentinoids. J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2020. May 5;ASN.2019090904. Available from: http://www.jasn.org/lookup/doi/10.1681/ASN.2019090904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.**.Zhan M, Doerfler RM, Xie D, et al. Association of Opioids and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs With Outcomes in CKD: Findings From the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2020. April; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272638620300421This study demonstrated that opioids were associated with a much higher risk of adverse kidney disease outcomes, death, and hospitalization in comparison to the modest relationship between NSAID use and adverse outcomes.

- 13.Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Castillo G, et al. Symptom Prioritization among Adults Receiving In-Center Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2018. May 7;13(5):735–45. Available from: http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2215/CJN.10850917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Lumby E, et al. Fostering Innovation in Symptom Management among Hemodialysis Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2019. January 7;14(1):150–60. Available from: http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2215/CJN.07670618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NIDDK. Hemodialysis Opioid Prescription Effort (HOPE) Consortium [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 29]. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/research-funding/research-programs/hemodialysis-opioid-prescription-effort-consortium

- 16.Jhamb M, Tucker L, Liebschutz J. When ESKD complicates the management of pain. Semin Dial [Internet]. 2020. May 4;sdi.12881. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sdi.12881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cukor D, Saggi SJ, Ahmad R, et al. Pain experienced by dialysis patients in two culturally diverse populations. Hemodial Int [Internet]. 2019. October;23(4):510–2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31374139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu H-J, Wu I-W, Hsu K-H, et al. The association between chronic musculoskeletal pain and clinical outcome in chronic kidney disease patients: a prospective cohort study. Ren Fail [Internet]. 2019. November;41(1):257–66. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31014149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bristowe K, Selman LE, Higginson IJ, et al. Invisible and intangible illness: a qualitative interview study of patients’ experiences and understandings of conservatively managed end-stage kidney disease. Ann Palliat Med [Internet]. 2019. April;8(2):121–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30691280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng MSN, Miaskowski C, Cooper B, et al. Distinct Symptom Experience Among Subgroups of Patients With ESRD Receiving Maintenance Dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 2020. January 23; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31981596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng MSN, So WKW, Wong CL, et al. Stability and Impact of Symptom Clusters in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease Undergoing Dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 2020;59(1):67–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31419542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourbonnais FF, Tousignant KF. Experiences of Nephrology Nurses in Assessing and Managing Pain in Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J [Internet]. 47(1):37–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32083435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jawed A, Moe SM, Moorthi RN, et al. Increasing Nephrologist Awareness of Symptom Burden in Older Hospitalized End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Am J Nephrol [Internet]. 2020;51(1):11–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31743896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth [Internet]. 2013. July;111(1):19–25. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0007091217329628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackman RP, Purvis JM, Mallett BS. Chronic nonmalignant pain in primary care. Am Fam Physician [Internet]. 2008/November/28 2008;78(10):1155–62. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19035063 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and Initial Validation of the PEG, a Three-item Scale Assessing Pain Intensity and Interference. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2009. June 6;24(6):733–8. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yelland MJ, Schluter PJ. Defining Worthwhile and Desired Responses to Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain Med [Internet]. 2006. January 1;7(1):38–45. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-lookup/doi/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geurts JW, Willems PC, Lockwood C, et al. Patient expectations for management of chronic non-cancer pain: A systematic review. Heal Expect [Internet]. 2017. December;20(6):1201–17. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/hex.12527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams AC de C, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2012. November 14; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient Outcomes in Dose Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Therapy. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2017. August 1;167(3):181 Available from: http://annals.org/article.aspx?doi=10.7326/M17-0598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garland EL, Brintz CE, Hanley AW, et al. Mind-Body Therapies for Opioid-Treated Pain. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2020. January 1;180(1):91 Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2753680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan MD, Turner JA, DiLodovico C, et al. Prescription Opioid Taper Support for Outpatients With Chronic Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain [Internet]. 2017. March;18(3):308–18. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1526590016303285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naylor MR, Naud S, Keefe FJ, et al. Therapeutic Interactive Voice Response (TIVR) to Reduce Analgesic Medication Use for Chronic Pain Management. J Pain [Internet]. 2010. December;11(12):1410–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1526590010004645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guarino H, Fong C, Marsch LA, et al. Web-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Chronic Pain Patients with Aberrant Drug-Related Behavior: Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Med [Internet]. 2018. December 1;19(12):2423–37. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/19/12/2423/4807510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brintz C, Cukor D, Cheatle M, et al. Non-pharmacological Treatments for Opioid Reduction in Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ramezanzadeh D, Manshaee G. The impact of acceptance and commitment therapy on pain catastrophizing: The case of hemodialysis patients in Iran. Int J Educ Psychol Res [Internet]. 2016;2(2):69 Available from: http://www.ijeprjournal.org/text.asp?2016/2/2/69/178868 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidarigorji A, Heidari Gorji M, Davanloo Aa. The efficacy of relaxation training on stress, anxiety, and pain perception in hemodialysis patients. Indian J Nephrol [Internet]. 2014;24(6):356 Available from: http://www.indianjnephrol.org/text.asp?2014/24/6/356/132998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rambod M, Sharif F, Pourali-Mohammadi N, et al. Evaluation of the effect of Benson’s relaxation technique on pain and quality of life of haemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet]. 2014. July;51(7):964–73. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020748913003544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burrai F, Lupi R, Luppi M, et al. Effects of Listening to Live Singing in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Study. Biol Res Nurs [Internet]. 2019;21(1):30–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30249121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roumelioti M-E, Steel JL, Yabes J, et al. Rationale and design of technology assisted stepped collaborative care intervention to improve patient-centered outcomes in hemodialysis patients (TĀCcare trial). Contemp Clin Trials [Internet]. 2018. October;73:81–91. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1551714418302921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Searle A, Spink M, Ho A, et al. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Rehabil [Internet]. 2015. December 13;29(12):1155–67. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269215515570379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Painter P, Carlson L, Carey S, et al. Physical functioning and health-related quality-of-life changes with exercise training in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2000. March;35(3):482–92. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272638600702022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yurtkuran M, Alp A, Yurtkuran M, et al. A modified yoga-based exercise program in hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Med [Internet]. 2007. September;15(3):164–71. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0965229906000732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bullen A, Awdishu L, Lester W, et al. Effect of Acupuncture or Massage on Health-Related Quality of Life of Hemodialysis Patients. J Altern Complement Med [Internet]. 2018. November;24(11):1069–75. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/acm.2018.0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim KH, Lee MS, Kim T-H, et al. Acupuncture and related interventions for symptoms of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016. June 28; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009440.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Randinitis EJ, Posvar EL, Alvey CW, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pregabalin in subjects with various degrees of renal function. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2003. March;43(3):277–83. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12638396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lal R, Sukbuntherng J, Luo W, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of gabapentin after administration of gabapentin enacarbil extended-release tablets in patients with varying degrees of renal function using data from an open-label, single-dose pharmacokinetic study. Clin Ther [Internet]. 2012. January;34(1):201–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22206794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blum RA, Comstock TJ, Sica DA, et al. Pharmacokinetics of gabapentin in subjects with various degrees of renal function. Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 1994. August;56(2):154–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8062491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong MO, Eldon MA, Keane WF, et al. Disposition of gabapentin in anuric subjects on hemodialysis. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 1995. June;35(6):622–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7665723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lobo ED, Heathman M, Kuan H-Y, et al. Effects of varying degrees of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of duloxetine: analysis of a single-dose phase I study and pooled steady-state data from phase II/III trials. Clin Pharmacokinet [Internet]. 2010. May;49(5):311–21. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20384393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nichols AI, Richards LS, Behrle JA, et al. The pharmacokinetics and safety of desvenlafaxine in subjects with chronic renal impairment. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2011. January;49(1):3–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21176719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Troy SM, Schultz RW, Parker VD, et al. The effect of renal disease on the disposition of venlafaxine. Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 1994. July;56(1):14–21. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8033490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lieberman JA, Cooper TB, Suckow RF, et al. Tricyclic antidepressant and metabolite levels in chronic renal failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 1985. March;37(3):301–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3971655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandoz M, Vandel S, Vandel B, et al. Metabolism of amitriptyline in patients with chronic renal failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 1984;26(2):227–32. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00630290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dawling S, Lynn K, Rosser R, et al. Nortriptyline metabolism in chronic renal failure: metabolite elimination. Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 1982. September;32(3):322–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7105623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dawlilng S, Lynn K, Rosser R, et al. The pharmacokinetics of nortriptyline in patients with chronic renal failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 1981. July;12(1):39–45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7248140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tutor-Crespo MJ, Hermida J, Tutor JC. Relative Proportions of Serum Carbamazepine and its Pharmacologically Active 10,11-Epoxy Derivative: Effect of Polytherapy and Renal Insufficiency. Ups J Med Sci [Internet]. 2008. January 12;113(2):171–80. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/2000-1967-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee CS, Wang LH, Marbury TC, et al. Hemodialysis clearance and total body elimination of carbamazepine during chronic hemodialysis. Clin Toxicol [Internet]. 1980. October;17(3):429–38. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7449356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vlavonou R, Perreault MM, Barrière O, et al. Pharmacokinetic characterization of baclofen in patients with chronic kidney disease: dose adjustment recommendations. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2014. May;54(5):584–92. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24414993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chauvin KJ, Blake PG, Garg AX, et al. Baclofen has a risk of encephalopathy in older adults receiving dialysis. Kidney Int [Internet]. 2020. May; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0085253820305524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolf E, Kothari NR, Roberts JK, et al. Baclofen Toxicity in Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2018;71(2):275–80. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28899601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brvar M, Vrtovec M, Kovac D, et al. Haemodialysis clearance of baclofen. Eur J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2007. December;63(12):1143–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17764008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Narabayashi M, Saijo Y, Takenoshita S, et al. Opioid rotation from oral morphine to oral oxycodone in cancer patients with intolerable adverse effects: an open-label trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2008. April;38(4):296–304. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18326541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kurita GP, Lundström S, Sjøgren P, et al. Renal function and symptoms/adverse effects in opioid-treated patients with cancer. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand [Internet]. 2015. September;59(8):1049–59. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25943005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malhotra BK, Schoenhard GL, de Kater AW, et al. The pharmacokinetics of oxycodone and its metabolites following single oral doses of Remoxy®, an abuse-deterrent formulation of extended-release oxycodone, in patients with hepatic or renal impairment. J Opioid Manag [Internet]. 11(2):157–69. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25901481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leuppi-Taegtmeyer A, Duthaler U, Hammann F, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oxycodone/naloxone and its metabolites in patients with end-stage renal disease during and between haemodialysis sessions. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2019;34(4):692–702. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30189012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Samolsky Dekel BG, Donati G, Vasarri A, et al. Dialyzability of Oxycodone and Its Metabolites in Chronic Noncancer Pain Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Pain Pract [Internet]. 2017;17(5):604–15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27589376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirvela M, Lindgren L, Seppala T, et al. The pharmacokinetics of oxycodone in uremic patients undergoing renal transplantation. J Clin Anesth [Internet]. 1996. February;8(1):13–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0952818095000925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Darwish M, Yang R, Tracewell W, et al. Effects of Renal Impairment and Hepatic Impairment on the Pharmacokinetics of Hydrocodone After Administration of a Hydrocodone Extended-Release Tablet Formulated With Abuse-Deterrence Technology. Clin Pharmacol drug Dev [Internet]. 2016. March;5(2):141–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27138027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ashby M, Fleming B, Wood M, et al. Plasma morphine and glucuronide (M3G and M6G) concentrations in hospice inpatients. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 1997. September;14(3):157–67. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9291702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bastani B, Jamal JA. Removal of morphine but not fentanyl during haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 1997. December;12(12):2802–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9430910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee MA, Leng ME, Tiernan EJ. Retrospective study of the use of hydromorphone in palliative care patients with normal and abnormal urea and creatinine. Palliat Med [Internet]. 2001. January;15(1):26–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11212464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paramanandam G, Prommer E, Schwenke DC. Adverse effects in hospice patients with chronic kidney disease receiving hydromorphone. J Palliat Med [Internet]. 2011. September;14(9):1029–33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21823925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perlman R, Giladi H, Brecht K, et al. Intradialytic clearance of opioids: methadone versus hydromorphone. Pain [Internet]. 2013. December;154(12):2794–800. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23973378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davison SN, Mayo PR. Pain management in chronic kidney disease: the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of hydromorphone and hydromorphone-3-glucuronide in hemodialysis patients. J Opioid Manag [Internet]. 4(6):335–6, 339–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19192761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Joh J, Sila MK, Bastani B. Nondialyzability of fentanyl with high-efficiency and high-flux membranes. Anesth Analg [Internet]. 1998. February;86(2):447 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9459269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kreek MJ, Schecter AJ, Gutjahr CL, et al. Methadone use in patients with chronic renal disease. Drug Alcohol Depend [Internet]. 1980. March;5(3):197–205. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6986247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Opdal MS, Arnesen M, Müller LD, et al. Effects of Hemodialysis on Methadone Pharmacokinetics and QTc. Clin Ther [Internet]. 2015. July 1;37(7):1594–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25963997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Furlan V, Hafi A, Dessalles MC, et al. Methadone is poorly removed by haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 1999. January;14(1):254–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10052536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Melilli G, Samolsky Dekel BG, Frenquelli C, et al. Transdermal opioids for cancer pain control in patients with renal impairment. J Opioid Manag [Internet]. 10(2):85–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24715663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hand CW, Sear JW, Uppington J, et al. Buprenorphine disposition in patients with renal impairment: single and continuous dosing, with special reference to metabolites. Br J Anaesth [Internet]. 1990. March;64(3):276–82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2328175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Filitz J, Griessinger N, Sittl R, et al. Effects of intermittent hemodialysis on buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine plasma concentrations in chronic pain patients treated with transdermal buprenorphine. Eur J Pain [Internet]. 2006. November;10(8):743–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16426877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moller PL, Sindet-Pedersen S, Petersen CT, et al. Onset of acetaminophen analgesia: comparison of oral and intravenous routes after third molar surgery. Br J Anaesth [Internet]. 2005. May;94(5):642–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15790675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koncicki HM, Unruh M, Schell JO. Pain Management in CKD: A Guide for Nephrology Providers. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2017. March;69(3):451–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27881247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kienzler J-L, Gold M, Nollevaux F. Systemic bioavailability of topical diclofenac sodium gel 1% versus oral diclofenac sodium in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2010. January;50(1):50–61. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19841157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lugo RA, Kern SE. The pharmacokinetics of oxycodone. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother [Internet]. 2004;18(4):17–30. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15760805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kinnunen M, Piirainen P, Kokki H, et al. Updated Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Oxycodone. Clin Pharmacokinet [Internet]. 2019;58(6):705–25. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30652261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, et al. Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2019. February 25; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD013273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McCrae JC, Morrison EE, MacIntyre IM, et al. Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol - a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2018. October;84(10):2218–30. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/bcp.13656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whelton A Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med [Internet]. 1999. May;106(5):13S–24S. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002934399001138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gunter BR, Butler KA, Wallace RL, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced cardiovascular adverse events: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther [Internet]. 2017. February;42(1):27–38. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jcpt.12484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simon LS, Weaver AL, Graham DY, et al. Anti-inflammatory and Upper Gastrointestinal Effects of Celecoxib in Rheumatoid Arthritis. JAMA [Internet]. 1999. November 24;282(20):1921 Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.282.20.1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leese PT, Hubbard RC, Karim A, et al. Effects of Celecoxib, a Novel Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitor, on Platelet Function in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2000. February;40(2):124–32. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1177/00912700022008766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lai KM, Chen T-L, Chang C-C, et al. Association between NSAID use and mortality risk in patients with end-stage renal disease: a population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019;11:429–41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31213924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sriperumbuduri S, Hiremath S. The case for cautious consumption. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens [Internet]. 2019. March;28(2):163–70. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/00041552-201903000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.**.Baker M, Perazella MA. NSAIDs in CKD: Are They Safe? Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2020. May; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272638620307241This article outlined the effects of NSAIDs on potential nephrotoxic events at each CKD Stage with a concurrent recommendation for NSAID use. The authors also give recommendations for NSAID dosing in CKD.

- 97.Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2015. June 15; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Derry S, Conaghan P, Da Silva JAP, et al. Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016. April 22; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD007400.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol [Internet]. 2015. February;14(2):162–73. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1474442214702510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Aitken E, McColl G, Kingsmore D. The Role of Qutenza® (Topical Capsaicin 8%) in Treating Neuropathic Pain from Critical Ischemia in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: An Observational Cohort Study. Pain Med [Internet]. 2016. July 14;pnw139. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/pm/pnw139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kienzler J-L, Gold M, Nollevaux F. Systemic Bioavailability of Topical Diclofenac Sodium Gel 1% Versus Oral Diclofenac Sodium in Healthy Volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. 2010. January;50(1):50–61. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1177/0091270009336234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fudin J, Raouf M. A Review of Skeletal Muscle Relaxants for Pain Management [Internet]. Practical Pain Management. 2017. Available from: https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/treatments/pharmacological/non-opioids/review-skeletal-muscle-relaxants-pain-management

- 103.Rein JL, Wyatt CM. Marijuana and Cannabinoids in ESRD and Earlier Stages of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2018. February;71(2):267–74. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272638617308107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24625 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bachhuber MA, Saloner B, Cunningham CO, et al. Medical Cannabis Laws and Opioid Analgesic Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1999–2010. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2014. October 1;174(10):1668 Available from: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cheikh Hassan HI, Brennan F, Collett G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Gabapentin for Uremic Pruritus and Restless Legs Syndrome in Conservatively Managed Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. 2015. April;49(4):782–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S088539241400445X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gunal AI, Ozalp G, Yoldas TK, et al. Gabapentin therapy for pruritus in haemodialysis patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2004. December 1;19(12):3137–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/ndt/gfh496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Simonsen E, Komenda P, Lerner B, et al. Treatment of Uremic Pruritus: A Systematic Review. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2017. November;70(5):638–55. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272638617307813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ishida JH, McCulloch CE, Steinman MA, et al. Gabapentin and Pregabalin Use and Association with Adverse Outcomes among Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2018. July;29(7):1970–8. Available from: http://www.jasn.org/lookup/doi/10.1681/ASN.2018010096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.**.Waddy SP, Becerra AZ, Ward JB, et al. Concomitant Use of Gabapentinoids with Opioids Is Associated with Increased Mortality and Morbidity among Dialysis Patients. Am J Nephrol [Internet]. 2020. May 19;1–9. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/507725This study highlights the risks of opioid and gabapentinoid co-prescribing in patients receiving dialysis.

- 111.Mersfelder TL, Nichols WH. Gabapentin: Abuse, Dependence, and Withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother [Internet]. 2016. March 31;50(3):229–33. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1060028015620800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nguyen T, Shoukhardin I, Gouse A. Duloxetine Uses in Patients With Kidney Disease. Am J Ther [Internet]. 2019;26(4):e516–9. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/00045391-201908000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gimbel JS, Richards P, Portenoy RK. Controlled-release oxycodone for pain in diabetic neuropathy: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology [Internet]. 2003. March 25;60(6):927–34. Available from: http://www.neurology.org/cgi/doi/10.1212/01.WNL.0000057720.36503.2C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hanna M, O’Brien C, Wilson MC. Prolonged-release oxycodone enhances the effects of existing gabapentin therapy in painful diabetic neuropathy patients. Eur J Pain [Internet]. 2008. August;12(6):804–13. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Muzaale AD, Daubresse M, Bae S, et al. Benzodiazepines, Codispensed Opioids, and Mortality among Patients Initiating Long-Term In-Center Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2020. June 8;15(6):794–804. Available from: http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2215/CJN.13341019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cheatle MD, Compton PA, Dhingra L, et al. Development of the Revised Opioid Risk Tool to Predict Opioid Use Disorder in Patients with Chronic Nonmalignant Pain. J Pain [Internet]. 2019. July;20(7):842–51. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1526590018306229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hadland SE, Levy S. Objective Testing – URINE AND OTHER DRUG TESTS. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am [Internet]. 2016. July;25(3):549–65. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1056499316300256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kinnunen M, Piirainen P, Kokki H, et al. Updated Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Oxycodone. Clin Pharmacokinet [Internet]. 2019. June 17;58(6):705–25. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40262-018-00731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Miotto K, Cho AK, Khalil MA, et al. Trends in Tramadol. Anesth Analg [Internet]. 2017. January;124(1):44–51. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/00000539-201701000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Aiyer R, Gulati A, Gungor S, et al. Treatment of Chronic Pain With Various Buprenorphine Formulations. Anesth Analg [Internet]. 2018. August;127(2):529–38. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/00000539-201808000-00036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.*.O’Brien MB, FRCPI T, Ahn JS, Chye, MBBS, FRACP, FFPMANZCA, FAChPM R, et al. Understanding transdermal buprenorphine and a practical guide to its use for chronic cancer and non-cancer pain management. J Opioid Manag [Internet]. 2019. March 1;15(2):147–58. Available from: https://www.wmpllc.org/ojs/index.php/jom/article/view/2402This review article provides an overview of transdermal buprenorphine and suggests that buprenorphine can be used in patients with renal disease without specific dose adjustment recommendations.

- 122.Breivik H, Ljosaa TM, Stengaard-Pedersen K, et al. A 6-months, randomised, placebo-controlled evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a low-dose 7-day buprenorphine transdermal patch in osteoarthritis patients naïve to potent opioids. Scand J Pain [Internet]. 2010. July 1;1(3):122–41. Available from: http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/sjpain.2010.1.issue-3/j.sjpain.2010.05.035/j.sjpain.2010.05.035.xml [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rauck RL, Potts J, Xiang Q, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of buccal buprenorphine in opioid-naive patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain. Postgrad Med [Internet]. 2016. January 2;128(1):1–11. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00325481.2016.1128307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mancher M, Leshner AI, editors. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives In: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives [Internet]. Washington (DC); 2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30896911 [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rudolf GD. Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am [Internet]. 2020. May;31(2):195–204. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1047965120300085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pergolizzi JV, Coluzzi F, Taylor R. Transdermal buprenorphine for moderate chronic noncancer pain syndromes. Expert Rev Neurother [Internet]. 2018. May 4;18(5):359–69. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14737175.2018.1462701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fishman MA, Scherer A, Topfer J, et al. Limited Access to On-Label Formulations of Buprenorphine for Chronic Pain as Compared with Conventional Opioids. Pain Med [Internet]. 2020. May 1;21(5):1005–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/21/5/1005/5614401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Woo J, Bhalerao A, Bawor M, et al. “Don’t Judge a Book by Its Cover”: A Qualitative Study of Methadone Patients’ Experiences of Stigma. Subst Abus Res Treat [Internet]. 2017. January 23;11:117822181668508. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1178221816685087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.