Abstract

A heterogeneous spectrum of clinical manifestations caused by mutations in ATP1A3 have been previously described. Here we report two cases of infantile‐onset cerebellar ataxia, due to two different ATP1A3 variants. Both patients showed slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia without paroxysmal or episodic symptoms. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed mild cerebellar cortical atrophy in both patients. Whole exome sequencing revealed a de novo heterozygous variant in ATP1A3 in both patients. One patient had the c.460A>G (p.Met154Val) variant, while the other carried the c.1050C>A (p.Asp350Lys) variant. This phenotype was characterized by a slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia since the infantile period, which has not been previously described in association with ATP1A3 variants or in ATP1A3‐related clinical conditions. Our report contributes to extend the phenotypic spectrum of ATP1A3 mutations, showing paediatric slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia with mild cerebellar atrophy alone as an additional clinical presentation of ATP1A3‐related neurological disorders.

Short abstract

This article is commented on by Ng on pages 11‐12 of this issue.

Abbreviations

- AHC

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood

- CAPOS syndrome

Cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensory motor hearing loss

What this paper adds.

Novel ATP1A3 variants are associated with slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia.

No paroxysmal or episodic symptoms were found in our cases arising from ATP1A3 variants.

The disease causing missense variants in ATP1A3 was first identified in families with rapid‐onset dystonia parkinsonism in 2004, and since then several ATP1A3‐related disorders have been recognized. 1 , 2 Classic phenotypes include alternating hemiplegia of childhood (AHC) 3 and rapid‐onset dystonia parkinsonism. 4 More recently other phenotypes have been associated with variants in ATP1A3, such as cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensory motor hearing loss (CAPOS syndrome), 5 relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia 6 /fever‐induced paroxysmal weakness encephalopathy, 7 early‐onset epileptic encephalopathy, 8 rapid‐onset ataxia in childhood 9 or adulthood, 10 childhood‐onset schizophrenia, 11 and autism spectrum disorders. 12

Paroxysmal episodic symptoms such as transient tonic or flaccid hemiplegia, dystonia, tonic seizures, episodic cerebellar ataxia, and abnormal ocular movements are the most common symptoms in patients with ATP1A3‐related disorders 1 , 2 (Table 1), except for childhood‐onset schizophrenia or autism spectrum disorders. Thus, identifying these symptoms can be helpful in clinical practice to aid in the early diagnosis of ATP1A3‐related disorders. However, in intermittent periods between these paroxysmal symptoms, most patients with ATP1A3‐related disorders present with persistent neurological deficits such as hypotonia, motor delay, ataxia, nystagmus, cognitive and behavioural dysfunction, or involuntary movements such as dystonia or choreoathetosis. 1 Interestingly, less severe ATP1A3 phenotypes have not been reported to date. Here we report two cases of ATP1A3‐related neurological disorders with infantile‐onset slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia and mild or moderate intellectual disability, but without paroxysmal episodic signs or motor fluctuation.

Table 1.

Main features reported in ATP1A3‐related disorders

| AHC 1 , 2 , 3 | RDP 1 , 2 , 4 | CAPOS 5 | RECA 6 /FIPWE 7 | ROA in childhood 9 or adulthood 10 | Present cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main symptoms |

Repeated attacks of hemiplegia that alternate in laterality Dystonic spells Seizure‐like episodes |

Rapid‐onset of dystonia and parkinsonism Prominent bulbar findings |

Cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensorineural hearing loss | Relapsing cerebellar ataxia and/or weakness | Rapid‐onset cerebellar ataxia | Slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia |

|

Paroxysmal or episodic symptoms Frequency |

Paroxysmal onset of hemiplegia Several times a month |

Rapid‐onset dystonia Rarely repeated |

Episodic cerebellar ataxia Less than once a year |

Episodic onset ataxia/weakness Less than once a year |

Rapid‐onset and stabilized ataxia Rarely repeated |

No paroxysmal nor episodic symptoms |

| Cerebellar symptoms | Ataxia (slowly progressive in some cases) | Ataxia | Ataxia (recover or persistent) | Ataxia (stepwise progressive) | Ataxia (rapid‐onset, stabilized) | Ataxia (insidious onset) |

| Brain MRI findings | Cerebellar cortical atrophy (in some cases) | Normal | Normal | Normal | Cerebellar cortical atrophy | Cerebellar cortical atrophy |

AHC, alternating hemiplegia of childhood; RDP, rapid‐onset dystonia parkinsonism; CAPOS, cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensorineural hearing loss; RECA, relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia; FIPWE, fever‐induced paroxysmal weakness and encephalopathy; ROA, rapid‐onset ataxia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

CASE REPORT

Two adolescent (case 1: male, 15y; case 2: female, 12y) patients from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry in Tokyo were studied. Ataxia was assessed using the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (0–40). This study was approved by the ethical committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Case 1

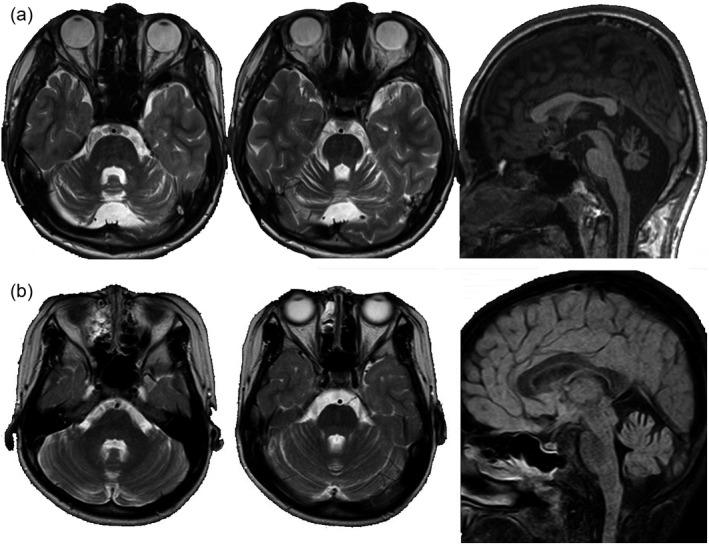

Case 1 was born after an uneventful pregnancy from non‐consanguineous parents. He was able to smile at 2 months, hold his neck up at 3 months, sit without support at 8 months, walk unassisted at 24 months, and vocalize words at 22 months. He presented unstableness at 12 months in his sitting position. Walking was always unsteady with wide‐based gait. He communicated using several words slowly and unclearly. At 15 years, his ataxic symptoms gradually became worse and he often fell while walking; he was referred to our hospital at this stage. Based on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, his IQ was 40 and the neurological examination performed at 15 years indicated cerebellar ataxia including saccadic eye movement, ocular motor apraxia, dysarthria, dysdiadochokinesis, dysmetria, intention tremor, decomposition of movements, and wide‐based gait. Deep tendon reflexes were within the normal range. His Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia score was 20. He had no positive family history. He had no telangiectasia, pes cavus, or visual/hearing disabilities. There were no signs of episodic abnormal ocular movement, seizures, dystonic events, bulbar symptoms, autonomic dysfunction, or respiratory disturbances. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed pure cerebellar cortical atrophy dominantly in the vermis (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in case 1 (a) and Case 2 (b). (a) Brain MRI findings (axial; T2‐weighted images, coronal; short‐T1 inversion recovery, sagittal: T1) of case 1 (age 15y). Diffuse cerebellar cortical atrophy is seen predominantly in the vermis. No abnormal signal intensity is seen. (b) Brain MRI findings (axial; T2‐weighted images, sagittal; fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery) of case 2 (age 7y). Diffuse mild cerebellar cortical atrophy is seen. No abnormal signal intensity is seen.

Case 2

Case 2 was born after an uneventful pregnancy from non‐consanguineous parents. She was able to hold her neck up at 5 months, sit without support at 15 months, walk unassisted at 2 years 11 months, and vocalize a word at 3 years. Her walking was always unsteady. At 7 years, she went to a hospital for unsteady walking, and brain MRI revealed a slight cerebellar cortical atrophy (Fig. 1b). Increased unsteadiness was reported when she had fever by viral infection. The unsteadiness gradually increased, and she was then referred to our hospital. Neurological examination revealed mild intellectual disability, saccadic eye movement and wide‐based gait, dysdiadochokinesis, dysmetria, and intention tremor. Normal deep tendon reflexes, visual acuity, and hearing ability were attested. Her Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia score was 12. She had no positive family history. She had no telangiectasia, pes cavus, or visual/hearing disabilities. There were no signs of episodic abnormal ocular movement, seizures, dystonic events, bulbar symptoms, autonomic dysfunction, or respiratory disturbances.

Both patients showed motor developmental delay, gradually progressive cerebellar ataxia, and mild intellectual disabilities.

RESULTS

Blood tests including alpha‐fetoprotein, albumin, cholesterol, lactate/pyruvate, and cytosine‐thymine‐guanine repeats in spinocerebellar ataxia 1, 2, 3, and dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy disclosed no abnormalities in both patients. From the clinical and examination findings, ataxia telangiectasia, mitochondrial encephalopathies, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy, congenital disorders of glycosylation, spinocerebellar ataxia 1, 2, 3, and dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy were ruled out. Then, trio whole exome sequencing was carried out using previously described methodology. 13

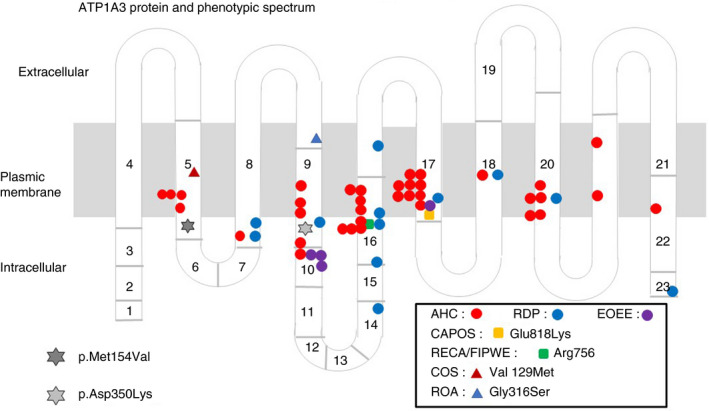

Variants in ATP1A3 (NM. 152296.5) were identified by whole exome sequencing: c.460A>G: p.(Met154Val) in case 1 and c.1050C>A: p.(Asp350Lys) in case 2. These variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the patients and their parents, and were found to be heterozygous de novo variants. These variants have not been reported previously, and computed analysis tools (SIFT, Polyphen2) predicted the likely pathogenic in each. Both variants are located on the intracellular region of Na+/K+‐ATPase α3 subunit (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

ATP1A3 protein and phenotypic spectrum. AHC, alternating hemiplegia of childhood; RDP, rapid‐onset dystonia‐parkinsonism; EOEE, early‐onset epileptic encephalopathy; CAPOS, cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensorineural hearing loss; RECA/FIPWE, relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia/fever‐induced paroxysmal weakness and encephalopathy; COS, childhood‐onset schizophrenia; ROA, rapid‐onset ataxia.

Whole exome sequencing excluded ataxia telangiectasia, ataxia‐oculomotor apraxia 1/2, spinocerebellar ataxia 5/13/29, and many other autosomal dominant or recessive cerebellar ataxia disorders in childhood.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to advance the understanding of phenotypes associated with variants in ATP1A3. Specifically, we reported two cases with symptoms that have not been previously associated with variants in ATP1A3. These symptoms include infantile‐onset of slowly progressive pure cerebellar ataxia and mild to moderate intellectual disability, which have not been previously reported in patients with ATP1A3‐related disorders (Table 1). Thus, these two cases did not show any characteristic symptoms of CAPOS 5 syndrome, relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia 6 /fever‐induced paroxysmal weakness encephalopathy, 7 nor any paroxysmal symptoms usually seen in AHC 3 and rapid‐onset dystonia parkinsonism. 4

Brain MRI in both patients revealed pure mild cerebellar cortical atrophy. In ATP1A3‐related disorders, brain MRI abnormalities are not generally detected. However, as we previously reported, 14 some patients with typical AHC show mild cerebellar cortical atrophy in adulthood. The cerebellar atrophy detected by brain MRI in both cases of the current study is similar to the atrophy previously reported in typical patients with AHC and the c.2401G>A (p.Asp801Asn) variant or c.2423C>T (p.Pro808Leu) variant in ATP1A3. 14 Therefore, pure mild cerebellar cortical atrophy may be a trait that can help to identify progressive cerebellar ataxia cases of ATP1A3‐related neurological disorders. The mechanisms of underlaying this relation are unknown, as the Na+/K+‐ATPase α3 subunit is ubiquitously expressed in the brain, including the cerebellar cortex, 15 which does not explain our current finding of pure cerebellar atrophy.

Recently, some adult patients with rapid‐onset ataxia were reported, 10 and patients with childhood‐onset ataxia‐dominant with ATP1A3 variants were also reported. 9 However, patients with infantile‐onset and pure slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia caused by ATP1A3 variants without any paroxysmal symptoms have not been reported. Currently, some phenotype/genotype correlations have been described. For instance, CAPOS syndrome is caused by p.Glu818Lys mutation 5 and relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia 6 /fever‐induced paroxysmal weakness encephalopathy 7 is caused by p.Arg756 Ser/His/Cys mutation. The mutations which cause AHC are mostly different from those causing rapid‐onset dystonia parkinsonism. In AHC, a correlation between a relatively severe phenotype with the genotype of p.Glu815Lys, and a moderate phenotype with the genotype of p.Asp801Asn and p.Gln947Arg has been reported. 3 In the present report, we describe for the first time two ATP1A3 variants, namely p.Met154Val (case 1) and p.Asp350Lys (case 2). These are both located in the intracellular cytoplasmic region of the Na+/K+‐ATPase, but further research is needed to clarify the potential modifications affecting the regulation of Na+/K+‐ATPase.

Although based on only two patients, we believe that the symptoms reported, namely infantile‐onset and slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia, could be a new subtype of ATP1A3‐related neurological disorders. Overall, the findings have important implications for the diagnosis of spinocerebellar ataxia.

Acknowledgements

This study was in part supported by the Intramural Research Grant (30‐6) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (M Sasaki), Research Committee of the Ataxia, Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation for Rare and Intractable Diseases, Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants, The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (M Sasaki), the Initiative on Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases (Grant number: 17ek0109151) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (K Kurosawa, K Kosaki), AMED under the grant numbers JP19ek0109280, JP19dm0107090, JP19ek0109301, JP19ek0109348, and JP18kk020501 (N Matsumoto), and JSPS KAKENHI under the grant numbers JP17H01539 (N Matsumoto). The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brashear A, Sweadner KJ, Cook JF, Swoboda KJ, Ozelius L. ATP1A3‐related neurologic disorders In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, 1993–2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosewich H, Sweney MT, DeBrosse S, et al. Research conference summary from the 2014 international task force on ATP1A3‐related disorders. Neurol Genet 2017; 3: e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sasaki M, Ishii A, Saito Y, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlations in alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Neurol 2014; 82: 482–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brashear A, Dobyns WB, de Carvalho Aguiar P, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of rapid‐onset dystonia‐parkinsonism (RDP) and mutations in the ATP1A3 gene. Brain 2007; 130: 828–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Demos MK, van Karnebeek CD, Ross CJ, et al. A novel recurrent mutation in ATP1A3 causes CAPOS syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014; 9: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dard R, Mignot C, Durr A, et al. Relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia related to an ATP1A3 mutation. Dev Med Child Neurol 2015; 57: 1183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yano ST, Silver K, Young R, et al. Fever‐induced paroxysmal weakness and encephalopathy, a new phenotype of ATP1A3 mutation. Pediatr Neurol 2017; 73: 101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paciorkowski AR, McDaniel SS, Jansen LA, et al. Novel mutations in ATP1A3 associated with catastrophic early life epilepsy, episodic prolonged apnea, and postnatal microcephaly. Epilepsia 2015; 56: 422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schirinzi T, Graziola F, Nicita F, et al. Childhood rapid‐onset ataxia: expanding the phenotypic spectrum of ATP1A3 mutations. Cerebellum 2018; 17: 489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sweadner KJ, Toro C, Whitlow CT, et al. ATP1A3 mutation in adult rapid‐onset ataxia. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0151429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smedemark‐Margulies N, Brownstein CA, Vargas S, et al. A novel de novo mutation in ATP1A3 and childhood‐onset schizophrenia. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud 2016; 2: a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takata A, Miyake N, Tsurusaki Y, et al. Integrative analyses of de novo mutations provide deeper biological insights into autism spectrum disorder. Cell Rep 2018; 22: 734–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sekiguchi F, Tsurusaki Y, Okamoto N, et al. Genetic abnormalities in a large cohort of Coffin‐Siris syndrome patients. J Hum Genet 2019; 64: 1173–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sasaki M, Ishii A, Saito Y, Hirose S. Progressive brain atrophy in alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Mov Disord Clin Prac 2017; 4: 406–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGrail KM, Phillips JM, Sweadner KJ. Immunofluorescent localization of three Na, K‐ATPase isozymes in the rat central nervous system: both neurons and glia can express more than one Na, K‐ATPase. J Neurosci 1991; 11: 381–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]