Abstract

Objective:

Hypertension is associated with renal immune cell accumulation and sodium retention. Lymphatic vessels provide a route for immune cell trafficking and fluid clearance. Whether specifically increasing renal lymphatic density can treat established hypertension, and whether renal lymphatics are involved in mechanisms of blood pressure regulation remain undetermined. Here, we tested the hypothesis that augmenting renal lymphatic density can attenuate blood pressure in established hypertension.

Methods:

Transgenic mice with inducible kidney-specific overexpression of VEGF-D (‘KidVD+’ mice) and KidVD–controls were administered a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, l-NAME, for 4 weeks, with doxycycline administration beginning at the end of week 1. To identify mechanisms by which renal lymphatics alter renal Na+ handling, Na+ excretion was examined in KidVDR mice during acute and chronic salt loading conditions.

Results:

Renal VEGF-D induction for 3 weeks enhanced lymphatic density and significantly attenuated blood pressure in KidVDR mice whereas KidVD mice remained hypertensive. No differences were identified in renal immune cells, however, the urinary Na+ excretion was increased significantly in KidVD+ mice. KidVD+ mice demonstrated normal basal sodium handling, but following chronic high salt loading, KidVD+ mice had a significantly lower blood pressure along with increased urinary fractional excretion of Na+. Mechanistically, KidVD+ mice demonstrated decreased renal abundance of total NCC and cleaved ENaCα Na+ transporters, increased renal tissue fluid volume, and increased plasma ANP.

Conclusion:

Our findings demonstrate that therapeutically augmenting renal lymphatics increases natriuresis and reduces blood pressure under sodium retention conditions.

Keywords: hypertension, lymphatic vessels, natriuresis, VEGF-D, VEGFR-3

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, or high blood pressure (BP), affects more than 45% of US adults, and is the largest contributing factor to mortality in the United States and the world. Although many factors contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension, inappropriate activation of the immune system and renal infiltration of pro-inflammatory immune cells have been identified in several experimental models and in patients with hypertension. The specific mechanisms that activate the immune system are still being discovered, however, once activated, immune cells infiltrate the kidney and inflammatory cytokines alter renal sodium (Na+) transport, affect renal blood flow, and aggravate hypertensive damage to the kidney.

Lymphatic vessels shape immune responses through their varied roles in immune function including trafficking of antigens and leukocytes from peripheral sites to lymph nodes, antigen presentation, modulation of immune cell function, and expression of immunomodulatory factors [1]. Lymphatic vessels are thus implicated in an increasing number of chronic inflammatory diseases [2,3], including obesity [4,5], and hypertension [6], and therapeutically manipulating lymphatic vessel growth and function positively alters the course of disease and improves outcomes [7,8]. We have previously demonstrated that renal lymphatic vessel density increases during aging-associated and hypertension-associated renal inflammation and injury in a compensatory manner [9]. Using our mouse model of inducible kidney-specific overexpression of the lymphangiogenic factor VEGF-D (KidVD), we demonstrated that selectively augmenting lymphatic density in the kidney reduced renal immune cell accumulation and prevented the development of salt-sensitive, nitric oxide inhibition-induced, and angiotensin II-induced hypertension [6,10]. Similarly, stimulating cardiac lymphangiogenesis decreased macrophage infiltration and lowered BP in rats fed a high salt diet [11].

Na+ retention is a hallmark of human [12,13] and experimental hypertension [14,15]. Evidence obtained from studies of renal transplantation, mutations in renal Na+ transporters, and diuretic actions demonstrate that renal fractional Na+ reabsorption is an essential regulator of effective extracellular volume and BP [16,17]. In 2009, Titze and colleagues outlined a novel concept in demonstrating that dermal lymphatic vessels regulate BP by undergoing hyperplasia in response to the interstitial accumulation of Na+ in mice fed a high salt diet [18]. Blocking lymphangiogenesis resulted in electrolyte accumulation and significantly elevated BP with no reported changes to the renal lymphatics. Past studies in dogs and rats have demonstrated that ligating the extrarenal collecting lymphatic vessels transiently increased BP and induced natriuresis via extracellular volume expansion [19,20]. The specific mechanisms by which lymphatic vessels within the kidney potentially regulate Na+ homeostasis thus remain undetermined.

In this study, we investigated the effects of renal lymphatic augmentation on the attenuation of BP in established hypertension. We hypothesized that the therapeutic induction of increased renal lymphatic density will lower BP in mice with nitric oxide inhibition-induced hypertension by reducing renal immune cell accumulation and increasing urinary Na+ excretion. We also characterized the effects of augmenting renal lymphatic density on the physiological regulation of renal Na+ excretion during acute and chronic salt-loading conditions.

METHODS

Animal care

All animal use protocols were approved by the Texas A&M University IACUC and were performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use and Care of Laboratory Animals.

Mice

KidVD

The generation of transgenic KidVD mice has been described previously [21]. TRE-VEGF-D mice were crossed with mice carrying a kidney promoter-driven rtTA (Cdh16, KSP) to generate KidVD mice that overexpress VEGF-D specifically in the kidney following doxycycline administration. The KSP-rtTA mouse was made available by the University of Texas Southwestern George M. O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center (P30DK079328). KidVD mice were backcrossed minimally seven generations to C57BL/6J. All mice were hemizygous for the TRE-VEGFD transgene, and were either wild-type or hemizygous for the KSP-rtTA transgene. All experiments were conducted with littermates, and doxycycline was administered to all mice for the same duration within each experiment to control for the effects of doxycycline. Mice were housed in a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. The l-NAME hypertension study involved five to six male mice per group. For the salt challenge studies, male and female mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups based on genotype availability. The baseline and chronic sodium-loading studies involved n = 5 male and 1 female KidVD–mice, and n = 2–3 male and 3–4 female KidVD+ mice, and data were pooled for analysis. All mice used in this study were between 12 and 16 weeks of age and had ad libitum access to diets and water. At the end of treatment protocols, mice were euthanized by exsanguination under deep isoflurane anesthesia and death was confirmed by cervical dislocation.

Experimental design

l-NAME hypertension

KidVD+ mice and KidVD− littermates were made hypertensive by providing l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME) (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) in their drinking water. After a week of l-NAME treatment, KidVD− and KidVD+ mice were administered doxycycline (0.2 mg/ml; doxycycline hyclate) concurrent with l-NAME in their drinking water for 3 weeks. All mice received normal Na+ diet containing 1% NaCl. Weekly SBP were determined in these mice using the tail-cuff method as described below. At the end of 4 weeks, mice were placed in diuresis cages and allowed to acclimatize for 24 h, following which urine was collected from individual mice over a period of 24 h. If less than 100 ml was collected in 24 h, urine analysis was excluded.

Baseline

KidVD+ mice and KidVD− littermates received normal Na+ diet containing 1% NaCl and 0.2 mg/ml doxycycline in their drinking water for 3 weeks. Mice were then placed in diuresis cages and acclimatized for 24 h, and urine was collected from individual mice over the next 24 h. SBP was measured by tail-cuff at the end of 3 weeks.

Acute salt loading

KidVD− and KidVD+ mice received regular diet (1% NaCl) and 0.2 mg/ml doxycycline drinking water for 3 weeks. Mice were fasted overnight for 12 h and were given 5% body weight 0.9% saline (9 mg/ml) intraperitoneally the following day. Immediately after injection, mice were placed in diuresis cages and hourly urine was collected from individual mice over the next 4 h. Only collected urine volumes at each hourly time point were included in the calculations.

Chronic salt loading

KidVD− and KidVD+ mice received a 4% high salt diet (Teklad Envigo, Huntingdon, United Kingdom) along with 0.2 mg/ml doxycycline and 1% saline (10 mg/ml NaCl) in their drinking water for 3 weeks. Following a 24-h acclimatization period, 24-h urine was collected from individual mice placed in diuresis cages. SBP values were recorded at the end of 3 weeks by tail-cuff.

Blood pressure determination

SBP was determined using the IITC Life Science noninvasive tail-cuff blood pressure acquisition system. Mice were acclimatized in a designated quiet area where all procedures were performed. Mice were handled gently and placed in prewarmed (34 °C) restrainers and allowed to acclimatize in the warming chamber for 5 min prior to beginning any recordings. SBP readings were determined by two independent, blinded investigators.

Flow cytometry

Kidneys were harvested and minced following decapsulation. The minced kidneys were digested in buffer containing enzymes Collagenase D (Roche Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and Dispase II (Sigma) at 37 °C for 1 h, and filtered through 100 and 40 μm strainers to obtain single cell suspensions. Red blood cells were lysed in NH4Cl/EDTA. Splenocytes were similarly isolated and used as antibody controls. Nonspecific Fc binding was blocked using an antimouse CD16/CD32 antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, California, USA), following which cells were incubated with fluorescent-conjugated antibodies against CD45, F4/80, CD11c, and CD3e for 10 min on ice. All antibodies were purchased from either BD Pharmingen or eBiosciences. Data were acquired on a BD LSR Fortessa X-20 flow cytometer using FACS DIVA software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using Flow Jo v7.6.2 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, Oregon, USA). CD3e+, CD3e, F4/80+, and CD11c+ populations were quantified within the CD45+ gate. Results are expressed as a percentage of CD45þ cells per kidney. Antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236. For gating strategy, refer to Supplemental Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236.

Urine and serum analysis

Serum and 24-h urine samples were analyzed for creatinine by capillary electrophoresis and for Na+ concentration using a Beckman AU400 Autoanalyzer at the University of Texas-Southwestern George M. O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center. For hourly urine samples from the acute salt loading study, urinary Na+ levels were measured using the LAQUAtwin Na+ meter (Horiba Scientific, Minami-ku Kyoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated using the creatinine clearance (ClCr) method. Urine was assessed for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels using the QuantiChrom Urea Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, California, USA). Urinary protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) and normalized to creatinine levels. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) levels were measured in the plasma using the Atrial Natriuretic Peptide EIA Kit (Sigma) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Renal immunofluorescence analysis

Kidney sections were cut 5 μm sagittally and were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton solution. The sections were blocked with 10% AquaBlock (EastCoastBio, North Berwick, Maine, USA) for 1 h at room temperature and were then incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight: goat polyclonal Podoplanin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), and rat monoclonal Endomucin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA). Alexa Flour 488 or 594 secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) were used for visualization. Antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236. Slides were mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and imaged using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope with Olympus Q5 camera. Images were captured at 20× magnification using the Olympus CellSens software (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Mouse kidneys were homogenized and total RNA was isolated using the Quick-RNA mini prep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, California, USA). 0.5 mg RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using the Qiagen RT2 First Strand kit (Germantown, Maryland, USA). To measure gene expression, 10 μl reactions were prepared using SYBR Green ROX qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen), nuclease-free water (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA), and primers (10 μmmol/l) (IDT, Coralville, Iowa, USA) in a 384-well plate in duplicate and run using the AB 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). All data were normalized to the expression levels of Rps18 and fold changes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method. All primer sequences used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 2, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236.

Immunoprecipitation and protein immunoblot analysis

Mouse kidneys were homogenized in Cell Lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA) and the supernatant was separated by centrifugation at 14,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher). In order to efficiently capture and detect phosphorylated NCC and NKCC2 from whole kidney lysate, 30 μg protein was first immunoprecipitated with antibodies against the total protein using Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Following this, the precipitated protein was resolved by gel electrophoresis and probed for the corresponding antibodies against NCC and NKCC2, followed by pThr/Ser/Tyr. For detection of other proteins, 30 μg of the total kidney homogenate was mixed with SDS sample buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. The proteins were separated by electrophoresis using 4–20% NuPage gels (Thermo Fisher), and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Biorad). Immunoblotting was performed by incubating the membrane at 4 °C overnight with the following primary antibodies: ENaCα, ENaCß, ENaCΥ, NHE3, pNHE3. Proteins were normalized to corresponding ß-actin. Secondary antibodies used were antirabbit and antimouse IgGs conjugated to Alexa-Flour 680 or IR800Dye (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). All antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236. The bands were detected using infrared visualization (Odyssey System, LI-COR Biosciences), and quantified by densitometry performed on the Odyssey software.

Isolation of renal tissue fluid

Tissue fluid from the kidney was isolated by a centrifugation technique adapted from protocols described previously [22]. The left kidney from each mouse was decapsulated, sagittally halved, and careful incisions were made restricted to the kidney cortex in one half of the kidney. Samples were suspended on 15 μm nylon mesh filters in preweighed centrifugal filter tubes. The tubes were spun at 6500g for 40 min at 4 °C, following which the tubes along with the kidney and isolated fluid were weighed again. The difference in weights served as the weight of the excised kidney. The tissue fluid was immediately collected from the bottom of the tube and the volumes were measured using a micropipette.

Statistical methods

All results are presented as bar graphs displaying mean ± SD except time-dependent graphs that display standard error (SE) for visual clarity. Blood pressures for the l-NAME hypertension study were analyzed by ANOVA for repeated measures. The two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used for comparison of means between genotypes. The criterion for significance was set at P< 0.05. All analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 7 software (La Jolla, California, USA).

RESULTS

Selective renal lymphatic expansion in KidVD+ mice attenuates blood pressure during l-NAME hypertension

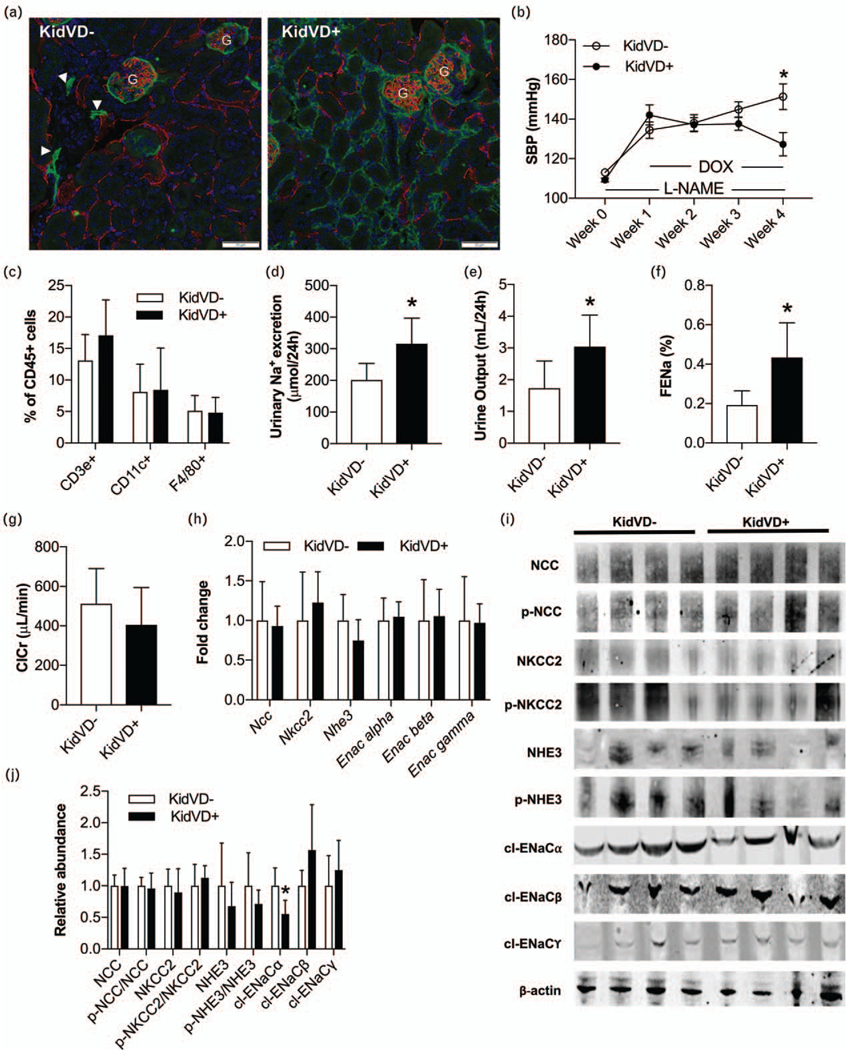

Chronic l-NAME administration has been shown to induce mild glomerulosclerosis, increase in glomerular afferent arteriole thickness, tubulointerstitial inflammation and injury, intrarenal angiotensin II upregulation, memory T-cell response induction, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which contribute to renal sodium retention and hypertension [23–25]. We have previously demonstrated that inducing kidney-specific lymphatic network expansion in the renal cortex of KidVDþ mice (Fig. 1a) prevents a rise in SBP and reduces renal immune cell accumulation during LNAME hypertension [6]. To determine if renal lymphangiogenesis could therapeutically lower BP in established hypertension, we made KidVD− and KidVD+ mice equally hypertensive by l-NAME administration (Fig. 1b). To allow for VEGF-D induction to elicit sufficient renal lymphangiogenesis, doxycycline was then administered concurrent with l-NAME for an additional 3 weeks. While KidVD− mice continued to be hypertensive throughout this period, SBP in KidVD+ mice was significantly attenuated following 3 weeks of VEGF-D induction (Fig. 1b). Flow cytometry analysis of kidneys from these mice did not, however, detect any significant changes in CD3e+ T-cells, CD11c+ cells, or F4/80+ monocytes, populations that were reduced when expanded lymphatics were present prior to the hypertensive stimuli (Fig. 1c) [6]. l-NAME hypertension also causes Na+ retention [26,27], and thus, we investigated whether the enhanced renal lymphatics in KidVD+ mice might affect Na+ excretion as an alternative antihypertensive mechanism. Indeed, KidVD+ mice displayed a significant increase in 24-h urinary Na+ excretion (Fig. 1d), accompanied by a significant increase in 24-h urine output (Fig. 1e). Urinary fractional excretion of Na+ was also significantly increased in KidVD+ mice (Fig. 1f) with equivalent ClCr between groups (Fig. 1g). mRNA levels determined by qPCR analysis did not reveal any differences in the expression of renal Na+ transporters (Fig. 1h). However, by protein immunoblot, we detected a significant reduction in cleaved (cl-) ENaCα (Fig. 1i and j), suggesting reduced ENaC-dependent Na+ reabsorption in KidVD+ mice.

FIGURE 1.

Selective renal lymphatic expansion in KidVD+ mice attenuates BP during l-NAME hypertension. (a) Immunofluorescent labeling of podoplanin (green) and endomucin (red) in the cortex of KidVD− and KidVD+ mice during l-NAME hypertension. ‘G’ indicates glomeruli. Arrowheads identify sparse native renal lymphatics. Blue = DAPI. Scale bars = 50 μm. (b) Weekly SBP in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice during l-NAME hypertension. (c) Flow cytometry quantitation of renal immune cells in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice during L-NAME hypertension. Results are expressed as percentages of CD45+ cells. (d) 24-h urinary Na+ excretion, (e) 24-h urine output, (f) Fractional excretion of Na+ (FENa), and (g) ClCr in KidVD mice during L-NAME hypertension. (h) mRNA expression of renal Na+ transporters in KidVD− mice. (i) Protein immunoblot analysis, and (j) relative abundance of renal Na+ transporters and their phosphorylation during L-NAME hypertension. n = 6 male mice per group, except western blots n = 4. Asterisk (*) indicates P less than 0.05 compared with KidVD-.

Renal sodium handling is not altered in KidVD+ mice at baseline

Following our observations, we characterized renal sodium handling in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice at baseline in the absence of hypertension. Although renal lymphatic density was greatly augmented in KidVD+ mice at the end of 3 weeks of doxycycline (Fig. 2a), there were no visible changes in renal blood capillary density (Fig. 2a). No differences in SBP were detected between KidVD− and KidVD+ mice (Fig. 2b) and other baseline renal characteristics were unchanged between groups (Table 1). KidVD+ mice did not exhibit changes in urinary Na+ excretion (Fig. 2c), urine output (Fig. 2d), fractional excretion of Na+ (Fig. 2e), or ClCr (Fig. 2f) compared with KidVD− mice. No changes were detected in the mRNA expression of renal Na+ transporters (Fig. 2g). Similarly, protein abundance and activity as measured by phosphorylation or cleavage of these transporters were not different between the groups (Fig. 2h and i). These results demonstrate that renal Na+ handling is unaltered in KidVD+ mice at baseline.

FIGURE 2.

Renal sodium handling is not altered in KidVD+ mice at baseline. (a) Immunofluorescent labeling of podoplanin (green) and endomucin (red) in the cortex of KidVD− and KidVD+ mice administered doxycycline for 3 weeks. ‘G’ indicates glomeruli. Arrowheads identify sparse native renal lymphatics. Blue = DAPI. Scale bars = 50μm. (b) SBP in KidVD and KidVDþ mice. (c) 24-h urinary Na+ excretion, (d) 24-h urine output, (e) Fractional excretion of Na+ (FENa), and (f) ClCr in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice. (g) mRNA expression of renal Na+ transporters in KidVD− and KidVD+ kidneys. (h) Protein immunoblot analysis, and (i) relative abundance of renal Na+ transporters and their phosphorylation in KidVD− and KidVD+ mouse kidneys. n = 5 male (m), 1 female (f) KidVD mice, and 3m, 3f KidVD+ mice; western blots n = 3m, 1f KidVD mice, and 2m, 2f KidVD+ mice.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of KidVD− and KidVD+ mice at baseline and under chronic salt load

| Baseline | Chronic salt load | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KidVD− | KidVD+ | KidVD− | KidVD+ | |

| Body weight (BW) (g) | 23.6 ± 4.1 | 22.1 ± 3.1 | 23.8 ± 1 | 20.2 ± 0.8a |

| Kidney weight (g) | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.12 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| Kidney weight/BW | 0.48 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 0.58 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1a |

| Heart weight (g) | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| Heart weight/BW | 0.52 ± 0.1 | 0.51 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.1 |

| Urine creatinine (mg/dl) | 34.5 ± 10.6 | 34.5 ± 10.5 | 27.8 ± 9.8 | 22.8 ± 9.2 |

| Blood urea Nitrogen (mg/dl) | 30.5 ± 4.1 | 34 ± 9.9 | 28.5 ± 2.3 | 33.3 ± 4.9 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01a | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.003 |

| Urine Na+ (mmol/l) | 97.4 ± 26.8 | 95.8 ± 35.3 | 613.6 ± 118 | 1003.6 ± 406.4a |

| Serum Na+ (mmol/l) | 148.2 ± 2.3 | 149.7 ± 3.1 | 152.9 ± 3.9 | 146.5 ± 3.5a |

Values are indicated as mean ± SD. For baseline studies, n = 5m, 1f KidVD− mice, and 3m, 3f KidVD+ mice. For chronic salt load studies, n = 5m, 1f KidVD− mice, and 2m, 4f KidVD+ mice. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of means. P less than 0.05.

Significance against respective KidVD−.

Renal sodium handling is not altered in KidVD+ mice following an acute sodium load

At the end of 3 weeks of doxycycline, KidVD− and KidVD+ mice were administered a single 5% body weight saline bolus and following the bolus, hourly urinary Na+ excretion was measured for 4 h. Hourly urinary total Na+ excretion was not different between KidVD− and KidVD+ mice (Fig. 3a), and similarly, there were no detectable changes in urine output (Fig. 3b). As the peak urinary Na+ excretion occurred at 2 h following the bolus, gene and protein expression of Na+ transporters were analyzed from kidneys of KidVD− and KidVD+ mice at this time point. However, no changes were detected in the mRNA (Fig. 3c), protein abundance or activity (phosphorylation or cleavage) (Fig. 3d and e) of these transporters. An acute sodium loading is therefore, handled equally by chow fed KidVD− and KidVD+ mice.

FIGURE 3.

Renal sodium handling is not altered in KidVD+ mice following an acute sodium load. (a) Hourly urinary Na+ excretion, and (b) urine output in fasted KidVD− and KidVD+ given an acute salt load following 3 weeks of doxycycline administration. (c) mRNA expression of renal Na+ transporters in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice. (d) Protein immunoblot analysis, and (e) relative abundance of renal Na+ transporters in KidVD− and KidVD+ mouse kidneys following an acute salt load. Hour 1: n = 7 male (m), 4 female (f) KidVD− mice, and 3m, 2f KidVD+ mice; hour 2: n = 7m, 4f KidVD− mice, and 3m, 2f KidVD+ mice; Hour 3: n = 5m, 5f KidVD− mice, and 2m, 2f KidVD+ mice; hour 4: n = 2m, 2f KidVD− mice, and 2m, 2f KidVD+ mice; western blots n = 2m, 2f mice per group.

KidVD+ mice exhibit increased urinary fractional excretion of Na+ during a chronic salt load

We then tested the effects of augmenting renal lymphatics on Na+ excretion in mice during chronic salt loading. We first confirmed the augmented lymphatic density in KidVD+ mice by immunofluorescent labeling for podoplanin (Fig. 4a). KidVD+ mice exhibited significantly lower SBP compared with KidVD− mice in response to chronic salt loading (Fig. 4b). No change in 24-h urinary Na+ excretion (Fig. 4c) or urine output (Fig. 4d) were identified in KidVD+ mice; however, urinary fractional excretion of Na+ was significantly increased in KidVD+ mice (Fig. 4e), whereas ClCr was unchanged between the groups (Fig. 4f). KidVD+ mice also demonstrated a significant increase in urinary Na+ concentration along with a significant reduction in serum Na+ concentration (Table 1). At the mRNA level, KidVD+ mice had significantly downregulated expression of the renal Na+ transporters Ncc, Nkcc2, and Nhe3 (Fig. 4g). Mirroring the reduced sodium reabsorption in KidVD+ l-NAME-treated mice, we again observed a significant reduction in the abundance of cl-ENaCα as well as total NCC in KidVD+ mice (Fig. 4h and i) by immunoblot.

FIGURE 4.

KidVD+ mice exhibit increased urinary fractional excretion of Na+ during a chronic salt load. (a) Immunofluorescent labeling of podoplanin (green) and endomucin (red) in the cortex of KidVD− and KidVD+ mice given a chronic high salt diet and water for 3 weeks. ‘G’ indicates glomeruli. Arrowheads identify sparse native renal lymphatics. Blue = DAPI. Scale bars = 50 μm. (b) SBP in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice. (c) 24-h urinary Na+ excretion, (d) 24-h urine output, (e) fractional excretion of Na+ (FENa), and (f) ClCr in high salt diet-fed KidVD− and KidVD+ mice. (g) mRNA expression of renal Na+ transporters in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice. (h) Protein immunoblot analysis, and (i) relative abundance and phosphorylation of renal Na+ transporters in KidVD− and KidVD+ mouse kidneys under chronic high salt loading. (j) Renal tissue fluid volume, and (k) plasma ANP levels in KidVD− and KidVD+ mice during baseline, acute salt loaded or chronic salt loaded conditions. n = 5 male (m), 1 female (f) KidVD− mice, and 2m, 4f KidVD+ mice, except western blots n = 3m, 1f KidVD− mice and 2m, 2f KidVD+ mice. Asterisk (*) indicates P less than 0.05 compared with KidVD−.

We then analyzed possible mechanisms by which augmenting renal lymphatics increases natriuresis to lower BP. We hypothesized that inducing extensive renal lymphatic expansion expands the interstitial space, and thus measured renal tissue fluid volume as a surrogate. Although unchanged at baseline or with an acute bolus, KidVD+ mice on chronic salt load had significantly more renal tissue fluid volume (Fig. 4j). We hypothesized that changing renal hydrodynamics would result in increased venous return through venous capillary resorption or through lymphatics via the thoracic duct, leading to myocardial stretching and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) release. Although no significant increase in cardiac mass was measured (Table 1), KidVD+ mice had a significant increase in plasma ANP levels, only when challenged with chronic sodium (Fig. 4k).

DISCUSSION

The major findings of the current study are that therapeutic induction of kidney-specific lymphangiogenesis increases natriuresis and attenuates BP during l-NAME-induced hypertension, inducing renal lymphangiogenesis does not alter renal Na+ handling at baseline or following an acute salt load, and augmenting renal lymphatic increases urinary fractional excretion of Na+ and lowers BP in mice during chronic high salt loading.

The contribution of renal inflammation to the development of hypertension is well established. Cytokines secreted by activated T cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages induce sodium retention and proteinuria, and deteriorate renal function [28]. Our group has demonstrated that enhancing renal lymphatic density before the onset of hypertension reduces renal accumulation of immune cells and prevents the development of l-NAME-induced, salt-sensitive, and angiotensin II-induced hypertension [6,10]. Here, we tested the effects of therapeutically enhancing renal lymphatic density to attenuate established hypertension. Inducing renal lymphangiogenesis during established hypertension attenuated BP in KidVD+ mice; however, populations of immune cells that were previously identified to be reduced during the prevention of hypertension were not altered in this study. While leading us to investigate Na+ handling, this finding does not exclude a role for lymphatic vessels in modulating immune responses during hypertension. In addition to regulating immune cell trafficking, lymphatic vessels influence immune outcomes by directly affecting dendritic cell and T-cell maturation and activation, and thus balance protective effector immune responses [29,30]. Particularly during hypertension, certain types of immune cells, namely T regulatory cells and M2 macrophages, protect against hypertensive injury by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines [31,32]. Renal lymphatics may therefore tune the immune response during hypertension.

Altered renal Na+ handling has a major pathogenic role in hypertension. In this study, we have demonstrated that an augmented renal lymphatic network induces natriuresis and lowers BP during l-NAME-induced hypertension and following a nonhypertensive chronic high salt challenge, thus establishing that renal lymphatics participate in maintaining Na+ homeostasis. Previous studies have identified roles for lymphatic vessels in Na+ homeostasis and BP regulation; for example, dermal lymphatics have been reported to play a role in electrolyte clearance from the skin and lower BP [18]. In rats given a high salt diet, overexpression of VEGF-C induced cardiac lymphangiogenesis and lowered BP [11]. Similarly, VEGF-C administered subcutaneously induced renal and skin lymphangiogenesis and lowered BP in mice fed a high salt diet [33]. However, the route of VEGF-C administration was not kidney-targeted in these studies, and thus their impacts on renal lymphatic vessels cannot be excluded. We have demonstrated that in our inducible, transgenic mouse model approach, lymphangiogenesis is restricted to the kidney and is not observed in other organs including the skin, heart, lung, and liver [6]. More importantly, augmenting renal lymphatics does not affect intrinsic renal Na+ handling, as evidenced by a lack of change in urinary Na+ excretion at baseline. In the acute saline bolus studies, urinary Na+ excretion in these mice prior to receiving the saline challenge would be similar to baseline conditions. Following the saline bolus, peak urinary Na+ excretion was achieved two hours after i.p. injection, similar to results from previous studies [34]. As interstitial Na+ accumulation and dermal lymphatics have been shown to alter Na+ homeostasis, we measured skin Na+ concentration in our study; however, we did not observe dermal interstitial Na+ accumulation during basal or high salt conditions (Supplemental Fig. 2a, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236). In addition, there were no changes in dermal lymphatic density in these mice (Supplemental Fig. 2b and c, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236), confirming that our lymphatic modulation was confined to the kidney.

The exact mechanisms by which augmented renal lymphatics induce natriuresis are still being determined. Although the proximal tubule segments are involved in reabsorbing the bulk of Na+ from glomerular filtrate, the distal nephron is involved in fine tuning sodium excretion to match intake [35]. l-NAME hypertension increases renal vascular resistance, and reduces renal blood flow and GFR, however, the magnitude of reduction of renal blood flow is usually larger, resulting in a rise in filtration fraction [23]. In this study, l-NAME was administered to both KidVD− and KidVD+ mice. Although not specifically tested, renal blood flow is likely to be reduced similarly in both groups, and hence a difference in filtration fraction would not be expected to contribute to the natriuretic response. In this study, we observed a reduction in the abundance of cl-ENaCα during l-NAME-induced hypertension, and a reduction in total NCC and cl-ENaCα following chronic high salt loading in KidVD+ mice. We observed a trend towards reduction in cl-ENaCα abundance in KidVD+ mice at baseline, and thus it is likely that augmenting renal lymphatics primes the kidney towards more efficiently excreting excess salt load. However, functional measures of urinary Na+ excretion were altered only when KidVD+ mice were challenged with Na+-retaining conditions, such as a chronic high salt diet or l-NAME administration. Inappropriate activation of the major distal nephron transporters NCC and ENaCα has been implied in mediating increased Na+ reabsorption under a high salt diet [36–38], suggesting that the downregulation of these transporters or their activity may contribute to the increased natriuresis in KidVD+ mice. These measures of transporter phosphorylation or ENaC subunit cleavage, thus serve as our measure of activity, however, direct activity was not measured and other mechanisms, such as membrane trafficking and endocytosis also regulate renal Na+ transporter activity [39,40].

An intriguing finding of this study is that augmenting renal lymphatics increases renal tissue fluid volume by almost two-fold specifically during a chronic salt load. The marked lymphatic expansion in KidVD+ mice thus appears to be a reservoir for fluid. Given the low compliance of the renal interstitium, this increase in fluid volume would be expected to raise interstitial hydrostatic pressure and induce natriuresis, as has been shown in previous studies [41,42]. It is interesting that during l-NAME hypertension, natriuresis occurs at the end of week 4 when BP is attenuated. Although a reduction in BP and hence a reduction in renal perfusion pressure could be expected to result in antinatriuresis, we interpret these findings as that an increase in renal tissue fluid volume and natriuresis mediate the effect on BP, and not vice versa; however, a specific cause-and-effect relationship has not been tested in this study. An increase in renal tissue fluid volume in KidVD+ mice at the end of week 4 is likely to have been initiated between weeks 3 and 4 when lymphatic vessels are fully formed. It is important to note that the hypertensive stimuli, such as l-NAME or high salt, and VEGF-C/D exposure are also likely to have effects on the native lymphatic architecture in KidVD− mice and the expanded lymphatic network in the KidVD+ mice. For example, nitric oxide inhibition has been shown to reduce lymph flow velocity in initial lymphatics, and increase contraction frequency of collecting lymphatic vessels [43,44]. Similarly, a high salt diet enhances lymphatic pump efficiency and lymph flow [45]. The expanded lymphatic network in KidVD+ mice might augment this response, leading to increased renal lymph flow and increased return to the heart, and causing increased plasma ANP levels during chronic salt load. VEGF-C stimulation of myocardial VEGFR-3 has been shown to promote ANP release [46], however, we ruled out this possibility in our study, as there was no increase in cardiac total or phospho-VEGFR-3 in chronic salt-loaded KidVD+ mice (Supplemental Fig. 2d and e, http://links.lww.com/HJH/B236). Although our previous work has demonstrated that sex-specific differences do not exist in KidVD+ mice in their lymphangiogenic potential or pressor response [6,10], the current study was not powered sufficiently to analyze outcomes by sex, and hence it cannot be ruled out that sex-specific mechanisms might be at play. Changes in renal renin or angiotensin II levels, other vasoactive or natriuretic hormones, glomerular function, and degree of tubuloglomerular feedback activation have not been measured in this study and may play a role in lymphatics effects on tubular Na+ handling [47].

In this study, we measured BP by the tail-cuff method and while we acknowledge the limitations of the technique in obtaining sensitive BP measurements, the technique has proven sufficient in detecting large differences in BP, such as seen in our study [48]. Attenuation of BP in both models occurred after 3 weeks of doxycycline administration, which coincided with the timing by which extensive lymphangiogenesis occurs in the model, suggesting that functional lymphatic vessels are required for BP attenuation; nevertheless, possible effects of VEGF-D within the kidney cannot be completely excluded. A recent study reported that podocyte-specific overexpression of VEGF-C reduced glomerular permeability and albuminuria during diabetic nephropathy [49]. Unlike VEGF-C, murine VEGF-D is specific for VEGFR-3, limiting direct blood vascular effects via VEGFR-2 [50]. Additionally, ascending vasa recta have been suggested to be lymphatic-like vessels and express VEGFR-3 in development [51]. Possible effects of VEGF-D signaling in other VEGFR-3 expressing cells within the kidney, therefore, cannot be fully excluded [52].

In conclusion, our study establishes that renal lymphatics help to maintain Na+ homeostasis during conditions of renal Na+ retention. At least in part by increasing natriuresis, the therapeutic induction of renal lymphangiogenesis lowers BP during established hypertension providing a new potential target in the worldwide hypertension epidemic.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Andrea J. Reyna for assistance with animal husbandry. We also thank the undergraduate and graduate students from our laboratory for their technical assistance.

This work was funded by an American Heart Association Grant in Aid (17GRNT33671220) to J.M.R. and American Heart Association Transformational Project Award (18TPA34170266) and NIH RO1 (DK120493) to B.M.M.

Abbreviations:

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- BP

blood pressure

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- Cdh16

cadherin-16

- ClCr

creatinine clearance

- ENaCα

epithelial Na channel alpha

- ENaCß

epithelial Na channel beta

- ENaCΥ

epithelial Na channel gamma

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- KidVD

(kid)ney-specific overexpression of (V)EGF-(D)

- KSP

kidney-specific protein

- l-NAME

l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

- NCC

NaCl cotransporter

- NHE3

sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3

- NKCC2

Na-K-2Cl cotransporter

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- pNHE3

phospho sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3

- pThr/Ser/Tyr

phospho threonine/serine/tyrosine

- rtTA

reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator

- TRE

tetracycline responsive element

- VEGF-C

vascular endothelial growth factor C

- VEGF-D

vascular endothelial growth factor D

- VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

- VEGFR-3

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breslin JW, Yang Y, Scallan JP, Sweat RS, Adderley SP, Murfee WL.Lymphatic vessel network structure and physiology. Compr Physiol 2018; 9:207–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baluk P, Tammela T, Ator E, Lyubynska N, Achen MG, Hicklin DJ, et al. Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest 2005; 115:247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huggenberger R, Ullmann S, Proulx ST, Pytowski B, Alitalo K, DetmarM. Stimulation of lymphangiogenesis via VEGFR-3 inhibits chronic skin inflammation. J Exp Med 2010; 207:2255–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty A, Barajas S, Lammoglia GM, Reyna AJ, Morley TS,Johnson JA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor–D (VEGF-D) overexpression and lymphatic expansion in murine adipose tissue improves metabolism in obesity. Am J Pathol 2019; 189:924–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia Nores GD, Cuzzone DA, Albano NJ, Hespe GE, Kataru RP,Torrisi JS, et al. Obesity but not high-fat diet impairs lymphatic function. Int J Obes 2016; 40:1582–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez Gelston CA, Balasubbramanian D, Abouelkheir GR, Lopez AH, Hudson KR, Johnson ER, et al. Enhancing renal lymphatic expansion prevents hypertension in mice. Circ Res 2018; 122:1094–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abouelkheir GR, Upchurch BD, Rutkowski JM. Lymphangiogenesis: fuel, smoke, or extinguisher of inflammation’s fire? Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017; 242:884–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aspelund A, Robciuc MR, Karaman S, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Lymphaticsystem in cardiovascular medicine. Circ Res 2016; 118:515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kneedler SC, Phillips LE, Hudson KR, Beckman KM, Lopez Gelston CA,Rutkowski JM, et al. Renal inflammation and injury are associated with lymphangiogenesis in hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2017; 312:F861–F869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balasubbramanian D, Lopez Gelston CA, Lopez AH, Iskander G, Tate W, Holderness H, et al. Augmenting renal lymphatic density prevents angiotensin II-induced hypertension in male and female mice. Am J Hypertens 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang GH, Zhou X, Ji WJ, Zeng S, Dong Y, Tian L, et al. Overexpression of VEGF-C attenuates chronic high salt intake-induced left ventricular maladaptive remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014; 306:H598–H609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endre T, Mattiasson I, Berglund G, Hulthén UL. Insulin and renal sodium retention in hypertension-prone men. Hypertension 1994; 23:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki T, Delea CS, Bartter FC, Smith H. The effect of high-sodium and low-sodium intakes on blood pressure and other related variables in human subjects with idiopathic hypertension. Am J Med 1978; 64:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Rudemiller NP, Patel MB, Karlovich NS, Wu M, McDonough AA, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor activation potentiates salt reabsorption in angiotensin II-induced hypertension via the NKCC2 co-transporter in the nephron. Cell Metab 2016; 23:360–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giani JF, Bernstein KE, Janjulia T, Han J, Toblli JE, Shen XZ, et al. Salt sensitivity in response to renal injury requires renal angiotensin-converting enzyme. Hypertension 2015; 66:534–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossier BC, Staub O, Hummler E. Genetic dissection of sodium andpotassium transport along the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron: importance in the control of blood pressure and hypertension. FEBS Lett 2013; 587:1929–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowley SD, Coffman TM. The inextricable role of the kidney inhypertension. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:2341–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Dahlmann A, Tammela T, MachuraK, et al. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med 2009; 15:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilienfeld RM, Friedenberg RM, Herman JR. The effect of renal lymphatic ligation on kidney and blood pressure. Radiology 1967; 88:1105–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilcox CS, Sterzel RB, Dunckel PT, Mohrmann M, Perfetto M. Renalinterstitial pressure and sodium excretion during hilar lymphatic ligation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 1984; 247 (2 Pt 2):F344–F351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammoglia GM, Van Zandt CE, Galvan DX, Orozco JL, Dellinger MT,Rutkowski JM. Hyperplasia, de novo lymphangiogenesis, and lymphatic regression in mice with tissue-specific, inducible overexpression of murine VEGF-D. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2016; 311:H384–H394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiig H, Aukland K, Tenstad O. Isolation of interstitial fluid from ratmammary tumors by a centrifugation method. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003; 284:H416–H424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro MO, Antunes E, de Nucci G, Lovisolo SM, Zatz R. Chronicinhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. A new model of arterial hypertension. Hypertension 1992; 20:298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itani HA, Xiao L, Saleh MA, Wu J, Pilkinton MA, Dale BL, et al. CD70 exacerbates blood pressure elevation and renal damage in response to repeated hypertensive stimuli. Circ Res 2016; 118:1233–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quiroz Y, Pons H, Gordon KL, Rincon J, Chavez M, Parra G, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from nitric oxide synthesis inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2001; 281:F38–F47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giani JF, Janjulia T, Kamat N, Seth DM, Blackwell WL, Shah KH, et al. Renal angiotensin-converting enzyme is essential for the hypertension induced by nitric oxide synthesis inhibition. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25:2752–2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bech JN, Nielsen EH, Pedersen RS, Svendsen KB, Pedersen EB. Enhanced sodium retention after acute nitric oxide blockade in mildly sodium loaded patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2007; 20:287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norlander AE, Saleh MA, Kamat NV, Ko B, Gnecco J, Zhu L, et al. Interleukin-17a regulates renal sodium transporters and renal injury in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 2016; 68:167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane RS, Femel J, Breazeale AP, Loo CP, Thibault G, Kaempf A, et al. IFNγ-activated dermal lymphatic vessels inhibit cytotoxic T cells in melanoma and inflamed skin. J Exp Med 2018; 215:3057–3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lund AW, Wagner M, Fankhauser M, Steinskog ES, Broggi MA, Spranger S, et al. Lymphatic vessels regulate immune microenvironments in human and murine melanoma. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, et al. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension 2011; 57:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harwani SC. Macrophages under pressure: the role of macrophage polarization in hypertension. Transl Res 2018; 191:45–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beaini S, Saliba Y, Hajal J, Smayra V, Bakhos JJ, Joubran N, et al. VEGFC attenuates renal damage in salt-sensitive hypertension. J Cell Physiol 2019; 234:9616–9630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veiras LC, Girardi ACC, Curry J, Pei L, Ralph DL, Tran A, et al. Sexual dimorphic pattern of renal transporters and electrolyte homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28:3504–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer LG, Schnermann J. Integrated control of Na transport along thenephron. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10:676–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mu SY, Shimosawa T, Ogura S, Wang H, Uetake Y, Kawakami-Mori F, et al. Epigenetic modulation of the renal b-adrenergic-WNK4 pathway in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nat Med 2011; 17:573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoorn EJ, Walsh SB, McCormick JA, Fürstenberg A, Yang CL, Roeschel T, et al. The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus activates the renal sodium chloride cotransporter to cause hypertension. Nat Med 2011; 17:1304–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aoi W, Niisato N, Sawabe Y, Miyazaki H, Tokuda S, Nishio K, et al. Abnormal expression of ENaC and SGK1 mRNA induced by dietary sodium in Dahl salt-sensitively hypertensive rats. Cell Biol Int 2007; 31:1288–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riquier-Brison AD, Leong PKK, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, Mc donough AA. Angiotensin II stimulates trafficking of NHE3, NaPi2, and associated proteins into the proximal tubule microvilli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2010; 298:F177–F186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haque MZ, Ortiz PA. Superoxide increases surface NKCC2 in the rat thick ascending limbs via PKC. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2019; 317:F99–F106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khraibi AA. Direct renal interstitial volume expansion causes exaggerated natriuresis in SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 1991; 261 (4 Pt 2): F567–F570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Granger JP, Scott JW. Effects of renal artery pressure on interstitial pressure and Na excretion during renal vasodilation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 1988; 255:F828–F833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagendoorn J, Padera TP, Kashiwagi S, Isaka N, Noda F, Lin MI, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulates microlymphatic flow via collecting lymphatics. Circ Res 2004; 95:204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gashev AA, Davis MJ, Zawieja DC. Inhibition of the active lymph pumpby flow in rat mesenteric lymphatics and thoracic duct. J Physiol 2002; 540:1023–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mizuno R, Isshiki M, Ono N, Nishimoto M, Fujita T. A high-salt diet differentially modulates mechanical activity of afferent and efferent collecting lymphatics in murine iliac lymph nodes. Lymphat Res Biol 2014; 13:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao T, Zhao W, Meng W, Liu C, Chen Y, Gerling IC, et al. VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 pathway promotes myocyte hypertrophy and survival in the infarcted myocardium. Am J Transl Res 2015; 7:697–709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cervenka L, Mitchell KD, Navar LG. Renal function in mice: effects ofvolume expansion and angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999; 10:2631–2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Davisson RL, Hall JE, Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in part 2: blood pressure measurement in experimental animals. Hypertension 2005; 45: 299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onions KL, Gamez M, Buckner NR, Baker SL, Betteridge KB, Desideri S, et al. VEGFC reduces glomerular albumin permeability and protects against alterations in VEGF receptor expression in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2019; 68:172–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baldwin ME, Catimel B, Nice EC, Roufail S, Hall NE, Stenvers KL, et al. The specificity of receptor binding by vascular endothelial growth factor-D Is different in mouse and man. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:19166–19171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kenig-Kozlovsky Y, Scott RP, Onay T, Carota IA, Thomson BR, Gil HJ, et al. Ascending vasa recta are angiopoietin/Tie2-dependent lymphatic-like vessels. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29:1097–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mu J, Worthmann K, Saleem M, Tossidou I, Haller H, Schiffer M. The balance of autocrine VEGF-A and VEGF-C determines podocyte survival. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2009; 297:F1656–F1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.