Abstract

Purpose

To define the time required to achieve the minimally clinically important difference (MCID), substantial clinical benefit (SCB) and patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS) for isolated arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM), and define preoperative and intraoperative factors that predict both early and late achievement of the stated metrics.

Methods

Patients who underwent isolated APM between 2014 and 2017 were retrospectively included. Patients without preoperative and 6-month patient-reported outcome measure scores, revision procedures, and significant concomitant procedures were excluded. The MCID, SCB, and PASS were calculated for knee-based patient-reported outcome measure scores using receiver operating curve analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis established the time required to achieve MCID, SCB and PASS. Hazard ratios from multivariate Cox regression allowed for the isolation of demographic and intraoperative factors predictive of the delayed time required to achieve MCID, SCB and PASS.

Results

A total of 126 patients (42.86% female, age: 48.9 ± 12.4 years) were included. Overall achievement rates ranged between 73.0% and 89.7% for MCID, 43.7% and 68.2% for SCB, and 50.8% and 68.3% for PASS. Median achievement time for MCID was 5.68-5.78 months, 5.73-6.05 months for SCB and 6.54-7.72 months for PASS. Multivariate Cox regression identified older age, workers’ compensation status, diabetes, and various tear types (i.e., longitudinal, transverse, bucket handle, complex) as predictors of early clinically significant outcome achievement (hazard ratio: 1.02-24.72), whereas subsequent steroid injection, higher preoperative scores and root and flap tears predicted delays in clinically significant outcome achievement (hazard ratio: 0.12-0.99).

Conclusions

The majority of patients undergoing APM achieve benefit within 6 months of surgery, with diminishing proportions at later timepoints. Important factors for consideration of the the timeline of achieving clinically significant outcome include age, diabetes, workers’ compensation, preoperative score, and tear type. The timeline for achieving improvement that was established by this study may aid in setting patient expectations and designing future outcome studies involving APM.

Study design

Level IV, Therapeutic Case Series.

With an annual incidence of 61-70 per 100,000 people, meniscal tears represent 1 of the most common knee pathologies in all of orthopedics.1 Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) represents the most commonly performed surgical intervention for meniscal tears,2,3 although arthroscopic meniscal repair is being performed with increasing frequency for root tears4,5 or vertical tears in vascularized areas in physiologically young and active patients.6,7 Additionally, because complication rates after APM are low,8 patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) offer valuable objective scales by which surgeons can measure outcomes and improve current guidelines. Younger age,9 minimal arthritis10 and simple tear types11,12 are a few predictors of favorable outcomes by this measure.13.

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated inconsistent results with respect to when patients plateau in improvement after APM.14,15 Some studies have reported a lack of significant PROM score improvements beyond 3 to 6 months of follow-up,16, 17, 18 but other studies suggest possible patient benefits beyond 12 months.19,20 When interpreting the results of trials reporting PROM scores longitudinally, it is particularly important to recognize the limitations associated with relying on statistical significance. Specifically, patients may not perceive statistically significant differences as true improvements indicating patient satisfaction.21 Clinically significant outcomes (CSOs) address the limitations associated with PROM reporting by defining outcome score thresholds above which patients report true clinical improvement.21 Although these threshold scores have been established for APM.13 there is little research regarding the time at which they are achieved.22,23 Defining the time-to-achievement relationship in APM is particularly relevant in the context of pay-for-performance models being increasingly adopted in the current American health care landscape.24 Time-to-achievement relationships may be also be particularly valuable in better defining evidence-based timelines for postoperative follow-up.22 Policy groups and physicians may use this information to optimize value-based pay structures and improve shared decision-making models in patients pursuing APM for meniscal tears.22,25

The purpose of this study was to define the time required to achieve the minimally clinically important difference (MCID), substantial clinical benefit (SCB) and patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS) for isolated APM and to define preoperative and intraoperative factors that predict both early and late achievement of the stated metrics. Our hypothesis was 3-fold: (1) that after APM, patients have the greatest probability of achieving CSO within 6 months of follow-up14,15,26; (2) that the rate of CSO achievement decreases over time thereafter19,20; (3) that among those with root tears, older patients (i.e., > 50 years) would demonstrate rates of CSO achievement similar to those of younger patients.27

Methods

Study Design, Outcome Measures and Patient Selection

PROM scores were aggregated in a retrospective fashion for all patients undergoing isolated APM between 2014 and 2017 by using Concurrent Procedural Terminology codes to query an electronic data collection service (Outcome Based Electronic Research Database; Universal Research Solutions, Columbia, Missouri) following standard institutional review board study approval. Inclusion criteria included receipt of an isolated, primary uni- or bicompartmental partial meniscectomy, a 2-year follow-up period and serial completion of PROM at preoperative and 6-month timepoints. Patients’ outcomes were aggregated across 5 surgeons. Exclusion criteria included revision procedures, concomitant ligamentous, cartilaginous and realignment procedures, biological augmentation, and a lack of consecutive PROM data to allow for the determination of MCID, SCB and PASS. Patients receiving chondroplasty for osteochondral defects were not excluded. Arthritis status was evaluated by the Kellgren-Lawrence grade on preoperative radiographs and confirmed on intraoperative arthroscopy.

Outcome measures were obtained using electronic questionnaires at preoperative, 6, 12, and 24 months postoperative timepoints. For postoperative timepoints, patients had a 2-month window (e.g., 5-7 months) to complete survey sets and received 1 reminder each week if forms were left unfilled. Validated measures of interest included the International Knee Documentation Committee Score, all Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) subscores, including KOOS Joint Replacement (JR), KOOS Physical Function Short Form (PS), KOOS Symptom, KOOS Pain, KOOS Activities of Daily Living (ADL), KOOS Sport, KOOS symptoms (Sx), and KOOS Quality of Life (QOL).

Statistical Analysis

The MCID, SCB and PASS values used in this analysis were derived from previously published research using the same institutional group.13 These values were derived using both anchor-based and distribution-based approaches relying on a Global Assessment Scale as previously described in the literature.28, 29, 30 Distribution-based MCID values were used for time-dependent analysis, given that area-under-curve values for anchor-based MCID calculations were all < 70%.13 Anchor-based values were used for SCB and PASS, given that area-under-curve values were all > 70% for SCB and > 85% for PASS.13 Reference case MCID, SCB and PASS for the International Knee Documentation Committee Score were 10.6, 25.3 and 57.9, respectively; for KOOS JR 10.7, 13.2, 68.3; for KOOS PS –8.2, –11.3, 26.2; for KOOS Symptom 7.1, 7.1, 71.4; for KOOS Pain 9.7, 22.2, 76.4; for KOOS ADL 11.0, 16.9, 89.0; for KOOS Sport 12.5, 27.5 and 55.6; and for KOOS QOL 15.6, 34.4 and 46.9, respectively. Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between time and PROM scores at preoperative, 6-month, 12-month and 24-month timepoints. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to determine the probability of achieving clinically significant outcomes as a function of time. Cumulative probabilities of outcome achievement were calculated based on survival analysis and reported using the true follow-up time data in days, calculated for each timepoint by subtracting the follow-up survey completion date from the preoperative survey completion date. A multivariate time-to-achievement Cox regression analysis determined the impact of demographic and intraoperative factors on the probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS as a function of time. Subgroup analysis utilized χ2 testing to examine achievement rates of pooled CSO for patients with arthritis and root tears based on age cut-offs (i.e., greater or less than 50 years). RStudio software, version 1.0.143 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient Demographics and Outcomes

A total of 126 patients was included in the analysis, with mean ± SD age of 46.9 ± 13.6 years, mean ± SD body mass index of 25.9 ± 6.1 and a total of 72 (57.1%) male patients. A total of 243 patients were excluded on the basis of concomitant procedure receipt or lack of serial PROM completion. Pertinent demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1, demonstrating pre- and intraoperative characteristics as well as postoperative variables included in the multivariate analysis. Of the 126 patients, 20 (15.9%) had subsequent procedures on the index knee within the 2-year follow-up time period, including 5 conversions to total knee arthroplasty and 2 conversions to unicompartmental arthroplasty of the index knee. One patient went on to require anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with APM for a cyclops lesion. A total of 9 patients required revision arthroscopy: 3 required subsequent APM, 1 underwent fat debridement, 2 patients had articular cartilage debridements, and 2 required osteochondral allograft transplants. Other subsequent procedures included 1 high tibial osteotomy and 1 patient requiring a distal femoral osteotomy.

Table 1.

Demographics, Preoperative and Intraoperative Variables

| Group Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 46.9 ± 13.6 |

| BMI | 25.9 ± 6.1 |

| Age (<40 years) | 34 (26.98%) |

| Female sex | 54 (42.86%) |

| Right-sided | 69 (54.76%) |

| Preoperative Characteristics | |

| Workers’ compensation | 17 (13.5%) |

| Smoking | 17 (13.5%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (4.8%) |

| Hypertension | 23 (18.3%) |

| Thyroid disease | 4 (3.2%) |

| Symptom duration (months) | 10.5 ± 12.5 |

| Operative and Postoperative Characteristics | |

| Pre-existing arthritis | 89 (70.6%) |

| Osteochondral defects | 32 (25.4%) |

| Chondroplasty | 25 (19.8%) |

| Subsequent injection | 35 (27.8%) |

| Subsequent procedure on index knee | 20 (15.9%) |

| Tear Classification | |

| Traumatic | 74 (58.73%) |

| Degenerative | 52 (41.27%) |

| Tear Locations | |

| Medial | 80 (63.5%) |

| Lateral | 63 (50.0%) |

| Bicompartmental | 17 (13.5%) |

| Tear Type | |

| Degenerative | 52 (41.27%) |

| Complex | 26 (21.43%) |

| Flap | 20 (15.75%) |

| Radial | 18 (14.29%) |

| Root | 11 (8.66%) |

| Oblique | 6 (4.76%) |

| Bucket handle | 5 (5.56%) |

| Vertical | 4 (3.17%) |

| Discoid | 1 (0.79%) |

NOTE. Age and BMI data are presented as mean + SD; all other variables are presented as total count (percentage).

BMI, body mass index.

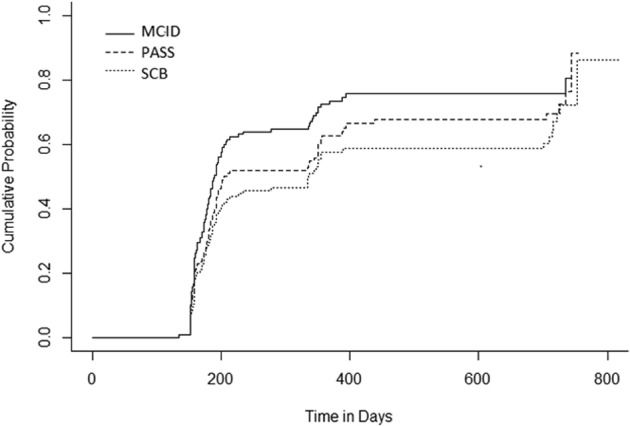

Mean PROM Improvement and Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis

Significant improvements were observed in the mean PROM scores between preoperative, 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year timepoints for each PROM (all P < 0.001, R2 = 0.13-0.21). MCID, SCB and PASS total achievement rates at 2 years are displayed in Fig 1. Median and mean achievement in months suggested right-tailed distributions for MCID (median = 5.68-5.78 months, mean = 6.39-6.91 months), SCB (median = 5.73-6.05 months, mean = 6.48-8.37 months) and PASS (median = 5.75-6.05, mean = 6.54-7.72 months). Cumulative probability graphs comparing rates of MCID, SCB, and PASS achievement by PROM are displayed in Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4, Fig 5, Fig 6, Fig 7, Fig 8 through 9.

Fig 1.

Total achievement of MCID, SCB and PASS by PROM. Percentages represent cumulative achievement rate at 2 years. (ADL, activities of daily living; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; JR, joint replacement; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; PROM, patient-reported outcome measures; QOL, quality of life; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; Sx, symptom score.)

Fig 2.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the IKDC. (IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee score; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 3.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the KOOS JR. (KOOS-JR: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement; MCID: minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 4.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the KOOS PS. (KOOS-PS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 5.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the KOOS SX. (KOOS-SX, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, Symptoms; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 6.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the KOOS Pain. (KOOS-Pain, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Pain Form; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 7.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the KOOS Activities of Daily Living. (KOOS-ADL, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Activities of Daily Living; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 8.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on the KOOS Sport. (KOS-SPORT, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Sport Form; MCID: minimally clinically important difference; PASS: patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Fig 9.

Cumulative probability of achieving MCID, SCB and PASS on KOOS QOL. (KOOS-QOL, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Quality of Life; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; SCB, substantial clinical benefit; time in days, true follow-up time from day of surgery.)

Multivariate Cox Regression: Factors Impacting Time to MCID, SCB and PASS

Tables 2, 3 and 4 demonstrate patient and operative factors found to be predictive of the time to MCID, SCB and PASS achievement, respectively. Older patients (2 PROMs, HR:1.02-1.03), those with complex tears (2 PROMs, HR:1.88-2.04) or a discoid meniscus (2 PROMs, HR:13.47-16.97) required less time to achieve MCID, whereas patients with medial sided tears (2 PROMs, HR:0.26-0.33), root tears (HR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.12-0.96) and higher preoperative scores (2 PROMs, HR:0.98) required more time to achieve MCID. With respect to SCB, workers’ compensation patients (HR:3.06, 95% CI:1.17-7.99), those suffering longitudinal (2 PROMs, HR:4.14-7.99), transverse (3 PROMs, HR range: 2.09-2.62), bucket handle (HR:3.67, 95% CI:1.25-10.77), or complex tears (HR:3.47, 95% CI:1.55-7.81) required less time to achieve SCB. Similar to MCID, patients with root tears (2 PROMs, HR:0.12-0.23) and higher preoperative scores (4 PROMs, HR:0.97-0.98) were more likely to achieve SCB at delayed time points. With respect to PASS, people with diabetes (HR:24.72, 95% CI:1.24-492.67), those with a discoid meniscus (3 PROMs, HR:5.65-30.94), a longitudinal tear (4 PROMs, HR:4.13-6.25), or higher preoperative scores (7 PROMs, HR:1.02-1.05) all experienced early PASS achievement (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox Regression: Factors Impacting the Time to Achieve MCID

| Time to Achieve MCID (Hazard Ratio, 95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC | KOOS JR | KOOS Pain | KOOS PS | KOOS SX | KOOS QOL | KOOS ADL | KOOS Sport | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00-1.05)∗ | 1.03 (1.00 -1.05)∗ | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.49 (0.24-0.98)∗ | 0.41 (0.20-0.83)∗ | 2.17 (1.05-4.50)∗ | |||||

| Medial tears | 0.33 (0.15-0.74)∗∗ | 0.26 (0.11-0.61)∗∗ | ||||||

| Discoid meniscus | 13.47 (1.06-169.76)∗ | 16.97 (1.31-219.49)∗ | ||||||

| Longitudinal tear | 6.41 (1.67-24.71)∗∗ | |||||||

| Root tear | 0.34 (0.12 –0.96)∗ | |||||||

| Flap tear | 0.46 (0.23-0.95)∗ | |||||||

| Complex tear | 1.88 (1.00-3.51)∗ | 2.04 (1.14-3.65)∗ | ||||||

| Subsequent injection | 0.52 (0.28-0.98)∗ | |||||||

| Subsequent procedure | 0.44 (0.20-0.96)∗ | 0.34 (0.18-0.67)∗∗ | 0.36 (0.17 -0.79) ∗ | |||||

| Preoperative score | 0.98 (0.97-0.99)∗∗ | 0.98 (0.96 - 0.99) ∗∗ | ||||||

NOTE. The following variables were found to be insignificant on Cox regression and were thus excluded from the table above: sex, worker’s compensation, BMI, smoking, diabetes, thyroid, preoperative score, pre-existing arthritis, lateral tear, bucket handle tear, oblique tear, transverse tear, horizontal tear, chondroplasty

ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; IKDC: International Knee Documentation Committee Score; JR, joint replacement; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; MCID, minimally clinically important difference; PS, Physical Function Short Form; QOL, quality of life; Sx, symptoms.

Denotes P <0.05.

Denotes P < 0.01; cells left blank denote nonsignificant relationships.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Regression: Factors Impacting the Time to Achieve SCB

| Time to Achieve SCB (Hazard Ratio, 95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC | KOOS JR | KOOS Pain | KOOS PS | KOOS SX | KOOS QOL | KOOS ADL | KOOS Sport | |

| Workers’ compensation | 3.06 (1.17-7.99)∗ | |||||||

| Lateral tear | 2.58 (1.07-6.23)∗ | |||||||

| Bucket handle tear | 3.67 (1.25-10.77)∗ | |||||||

| Longitudinal tear | 4.14 (1.07-15.94)∗ | 7.99 (2.04-31.29)∗∗ | ||||||

| Transverse tear | 2.62 (1.12-6.16)∗ | 2.09 (1.05-5.16)∗ | 2.42 (1.18-4.95)∗ | |||||

| Root tear | 0.23 (0.07-0.77)∗ | 0.12 (0.02 -0.62) ∗ | ||||||

| Complex tear | 3.47 (1.55-7.81)∗∗ | |||||||

| Subsequent injection | 0.33 (0.14-0.81)∗ | 0.38 (0.17 -0.83) ∗ | ||||||

| Preoperative score | 0.98 (0.96-1.00)∗ | 0.98 (0.97-1.00)∗∗ | 0.97 (0.96-0.99)∗∗ | 0.97 (0.95 -0.98) ∗∗ | ||||

NOTE. The following variables were also found to be insignificant on Cox regression and were thus excluded from the table above: sex, age, body mass index, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, thyroid, symptom duration, pre-existing arthritis, chronic tear, medial tear, discoid meniscus, flap tear, chondroplasty, and receipt of a subsequent procedure.

ADL, activities of daily living; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee score; JR, joint replacement; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PS, Physical Function Short Form; QOL, quality of life; SCB, ;substantial clinical benefit; Sx, symptoms.

Denotes P < 0.05.

Denotes P < 0.01; cells left blank denote nonsignificant relationships.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox Regression: Factors Impacting the Time to Achieve PASS

| Time to Achieve PASS (Hazard Ratio, 95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC | KOOS JR |

KOOS Pain |

KOOS PS | KOOS SX | KOOS QOL | KOOS ADL | KOOS Sport | |

| Diabetes | 24.72 (1.24 – 492.67) ∗ | |||||||

| Chronic tears | 0.41 (0.20-0.83)∗ | |||||||

| Medial tears | 2.63 (1.07-6.47)∗ | |||||||

| Bucket handle tear | 3.48 (1.11-10.83)∗ | |||||||

| Discoid meniscus | 23.34 (1.57-344.7)∗ | 5.65 (1.55-20.59)∗∗ | 30.94 (1.87 – 513.20) ∗ | |||||

| Longitudinal Tear | 6.25 (1.62-24.13)∗∗ | 4.13 (1.03-16.48)∗ | 5.47 (1.32-22.70)∗ | 6.16 (1.65-22.97)∗∗ | ||||

| Transverse tear | 3.98 (1.75-9.03)∗∗ | |||||||

| Complex tear | 3.44 (1.69-7.00)∗∗ | |||||||

| Subsequent injection | 0.25 (0.10-0.67)∗∗ | 0.42 (0.20-0.90)∗ | ||||||

| Preoperative score | 1.04 (1.02-1.06)∗∗ | 1.05 (1.02-1.07)∗∗ | 1.03 (1.01-1.04)∗∗ | 0.96 (0.93-0.98)∗∗ | 1.03 (1.01-1.05)∗∗ | 1.04 (1.02-1.06)∗∗ | 1.02 (1.00-1.03)∗ | 1.03 (1.01–1.04)∗∗ |

NOTE. The following variables were also found to be insignificant on Cox regression and were, thus, excluded from the table above: sex, age, workers’ compensation, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, thyroid disease, symptom duration, pre-existing arthritis, oblique tears, horizontal tears, root tears, flap tears, chondroplasty, subsequent procedures.

Cells left blank denote nonsignificant relationships.

IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee Score; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; JR, joint replacement; PASS, patient acceptable symptomatic state; PS, Physical Function Short Form; Sx, symptoms; ADL, activities of daily living; QOL: quality of life.

Denotes P < 0.05.

Denotes P < 0.01.

Subgroup Analysis for Age, Arthritis, Root Tears

Achievement of MCID, SCB and PASS was pooled for all PROMs, and achievement rates were examined. Patients with pre-existing arthritis were less likely to achieve any CSO than those without arthritis (66.2% vs 77.4%, P < 0.001). Of those patients with arthritis, patients younger than 50 years of age were more likely to achieve CSO than those older than 50, respectively (73.9% vs 67.5%, P < 0.001). Patients with root tears achieve a CSO 66.1% of the time, and every patient with a root tear demonstrated evidence of arthritis on diagnostic arthroscopy (n = 11, 100%). No significant differences in CSO achievement between those younger versus older than 50 years of age were found in patients with root tears (68.3% vs. 62%, P = 0.22).

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that patients treated with isolated APM for a meniscal tear have the greatest likelihood of MCID, SCB and PASS achievement within the first 6 postoperative months. Rates of outcome achievement after 6 months decrease with increasing time. Important risk factors, such as age greater than 50 years old, tear type, diabetes, and preoperative level of function were found to impact significantly the time required for such patients to achieve these clinical outcomes. This study further emphasizes the importance of these variables and the need to account for them when setting patients’ expectations, designing future studies and determining patient-specific timelines for return to work and sport.

Previous outcome studies have demonstrated that the greatest improvements in PROMs occur within 6 months of follow-up after APM, and they appear to plateau thereafter.16,17,31 Our study supports this notion by demonstrating mean MCID achievement rates ranging from 6.39-6.91 months and median achievement times of MCID, SCB and PASS ranging between 5.67 and 6.05 months. Furthermore, the majority of complications associated with APM occur sooner after surgery,32 and previous studies have demonstrated that predictors of short-term outcomes differ from predictors of long-term outcomes in APM.33 Beyond this time frame of improvement, there is a greater likelihood of confounding factors that may affect outcomes, such as subsequent injury or illness.34 Studies examining long-term outcomes after APM are important in establishing maintained clinical benefits,19 informing cost analyses35 and examining rate of total knee arthroplasty conversion.36, 37, 38 However, the importance of short-term outcomes (i.e., ≤ 6 months) should not be overlooked in future studies and during outcomes collection because they provide particularly impactful benefits directly attributable to the surgery.

This study demonstrated that older patients require significantly less time to achieve CSO across multiple PROMs. Meniscal tears in older patients are more often a result of degenerative pathology rather than trauma and may portend progression toward osteoarthritis.9,39,40 The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, among other societies, recommended, in 2008, that great caution be exercised when considering APM in patients with osteoarthritis, mechanical symptoms, degenerative meniscal changes, or flap tears in the presence of joint-space narrowing or significant chondral loss.41,42 APM rates have, consequently, decreased by more than 5% a year between 2010 and 2015 in those older than 50 years of age.43 Despite this, in well indicated patients, the present study demonstrates that elderly patients were able to obtain significant symptom relief and clinical benefit in a short interval. In our patient group, patients with pre-existing arthritis were less likely to achieve CSO than those without arthritis (66.2% vs 77.4%). These findings are expected, as meniscectomy of degenerative tears does not address symptoms caused by pre-existing osteoarthritis. Additionally, meniscal removal could potentially lead to further joint narrowing, chondral degeneration and kinematic changes.44, 45, 46, 47, 48 This supports the role of APM in providing symptomatic relief and perhaps, consequently, improving activity levels in a subset of older patients, particularly those with mild levels of pre-existing arthritis.

Medial meniscus posterior root tears are an especially important consideration because these injuries are biomechanically comparable to a completely meniscectomized knee.4 Several studies have suggested that meniscal root repairs should be performed to treat this type of injury, rather than meniscectomy.49, 50, 51 Previous studies have additionally demonstrated that those with root tears have reduced odds of MCID, SCB and PASS for KOOS Sx and Sport subscores after APM.13 Recent literature suggests that APM may be able to provide symptomatic relief in patients with well-aligned, nonarthritic joints.48 However, the majority of patients within this group of patients showed evidence of mild arthritis on arthroscopy. The present study further demonstrated that patients undergoing APM for root tears experience significant delays with respect to achievement of MCID and SCB on KOOS Sx. When considered in the context of recent literature suggesting minimal postoperative benefits52 and heightened risk of osteoarthritis progression in those receiving APM for medial meniscus posterior root tears,51 our findings provide further evidence in support of the notion that root repair should be the preferred initial intervention for the treatment of medial meniscus posterior root tears.51 Future studies should consider examining rates of CSO achievement between APM and root repair.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations that all readers must consider. First, the present study lacks follow-up data for any PROM data prior to 6 months, so conclusions regarding clinical improvement prior to this time interval could not be determined. Thus, we were unable to determine more precisely at which times outcomes were attained. Despite this limitation, our cumulative probability data still suggest the overall trend of early outcome achievement with decreasing returns over time. Additionally, our meniscectomy data were collected across 5 surgeons who may have differences with respect to surgical technique, rehabilitative protocols and patient compliance. Third, patient compliance with respect to PROM completion was a concern in the design of our study because compliance rates have previously been demonstrated to decrease over postoperative follow-up. Our inclusion criteria helped to address this limitation by requiring completion of PROM at consecutive timepoints. Fourth, the focus of this study was specifically the time to achievement of CSO, without commenting on the amount of clinical benefit patients achieved with respect to surgery. Although MCID, SCB and PASS represent differential levels of clinical benefit, outcomes were pooled for the CSO analysis in order analyze the time to achievement of CSO. Last, a minority of patients underwent subsequent surgeries within the follow-up time period, representing a potential confounder.

Conclusion

The majority of patients undergoing APM achieve benefit within 6 months of surgery, whereas diminishing proportions do so at later times. Important factors for consideration in the timeline of achieving CSO include age, diabetes, workers’ compensation, preoperative score, and tear type. The timeline for achieving improvement that was established by this study may aid in setting patients’ expectations and designing future outcome studies involving APM.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: A.B.Y. receives research support from Arthrex and NuTech; and hospitality fees from Smith and Nephew. B.F. receives fellowship support from Smith and Nephew and Ossur; royalties from Elsevier; research support from Arthrex, stock or stock options from Jace Medical, and receives research support and consultant fees from Stryker. B.C. receives IP royalties and research support from Arthrex; research support from Aesculap/B.Briaun; is on the editorial or governing boards of American Journal of Orthopaedics, American Journal of Sports Medicine, and Cartilage; is a board or committee member of Arthroscopy Association of North America; receives other financial or material support from Athletico; and IP royalties from Elsevier Publishing. N.L. receives research support from Arthrex and DJ Orthopaedics, publishing royalties and material support from Arthroscopy, personal fees from Orthospace, and nonfinancial support and publishing royalties from Vindico Medical-Orthopedics Hyperguide. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Awarded Podium at the Arthroscopy Association of North America Annual Meeting, 2019.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Mitchell J., Graham W., Best T.M., et al. Epidemiology of meniscal injuries in US high school athletes between 2007 and 2013. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3814-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen K.A., Hall M.J., Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S., Bosque J., Meehan J.P., et al. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: A comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:994–1000. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pache S., Aman Z.S., Kennedy M., et al. Meniscal root tears: Current concepts review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018;6:250–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonasia D.E., Pellegrino P., D'Amelio A., et al. Meniscal root tear repair: Why, when and how? Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2015;7:5792. doi: 10.4081/or.2015.5792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryceland J.K., Powell A.J., Nunn T. Knee Menisci. Cartilage. 2017;8:99–104. doi: 10.1177/1947603516654945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mordecai S.C., Al-Hadithy N., Ware H.E., Gupte C.M. Treatment of meniscal tears: An evidence based approach. World J Orthop. 2014;5:233–241. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaufils P., Becker R., Verdonk R., et al. Focusing on results after meniscus surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roos E.M., Ostenberg A., Roos H., et al. Long-term outcome of meniscectomy: symptoms, function, and performance tests in patients with or without radiographic osteoarthritis compared to matched controls. Osteoarthrit Cartil. 2001;9:316–324. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eijgenraam S.M., Reijman M., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M.A., et al. Can we predict the clinical outcome of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:514–521. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams R.J., 3rd, Warner K.K., Petrigliano F.A., et al. MRI evaluation of isolated arthroscopic partial meniscectomy patients at a minimum five-year follow-up. HSS J. 2007;3:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s11420-006-9031-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatain F., Adeleine P., Chambat P., et al. A comparative study of medial versus lateral arthroscopic partial meniscectomy on stable knees: 10-year minimum follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:842–849. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowd A.K., Lalehzarian S.P., Liu J.N., et al. Factors associated with clinically significant patient-reported outcomes after primary arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:1567–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monk P., Garfjeld Roberts P., Palmer A.J., et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965–973. doi: 10.1177/0363546516650180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson P.R., Altman D.G., Blazeby J.M., et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: Issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz J.N., Brophy R.H., Chaisson C.E., et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1675–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sihvonen R., Paavola M., Malmivaara A., et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2515–2524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yim J.H., Seon J.K., Song E.K., et al. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1565–1570. doi: 10.1177/0363546513488518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrlin S.V., Wange P.O., Lapidus G., et al. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:358–364. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sihvonen R., Paavola M., Malmivaara A., et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus placebo surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear: A 2-year follow-up of the randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:188–195. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris J.D., Brand J.C., Cote M.P., et al. Research pearls: The significance of statistics and perils of pooling. Part 1: Clinical versus statistical significance. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1102–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nwachukwu B.U., Chang B., Adjei J., et al. Time required to achieve minimal clinically important difference and substantial clinical benefit after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:2601–2606. doi: 10.1177/0363546518786480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flores S.E., Sheridan J.R., Borak K.R., Zhang A.L. When do patients improve after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement? A prospective cohort analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:3111–3118. doi: 10.1177/0363546518795696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman A.H., Kates S. Pay-for-performance in orthopedics: How we got here and where we are going. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:212–217. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9404-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nwachukwu B.U., Hamid K.S., Bozic K.J. Measuring value in orthopaedic surgery. JBJS Rev. 2013;1 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.M.00067. 01874474-201311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lubowitz J.H., Ayala M., Appleby D. Return to activity after knee arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:58–61, e54. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Essilfie A., Kang H.P., Mayer E.N., et al. Are orthopaedic surgeons performing fewer arthroscopic partial meniscectomies in patients greater than 50 years old? A national database study. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:1152–1159, e1151. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.10.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copay A.G., Subach B.R., Glassman S.D., et al. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: A review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nwachukwu B.U., Chang B., Fields K., et al. Defining the "substantial clinical benefit" after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:1297–1303. doi: 10.1177/0363546516687541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nwachukwu B.U., Chang B., Kahlenberg C.A., et al. Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents provides clinically significant outcome improvement. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1812–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorlund J.B., Englund M., Christensen R., et al. Patient reported outcomes in patients undergoing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for traumatic or degenerative meniscal tears: Comparative prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;356:j356. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abram S.G.F., Judge A., Beard D.J., Price A.J. Adverse outcomes after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: A study of 700 000 procedures in the national Hospital Episode Statistics database for England. Lancet. 2018;392:2194–2202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31771-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabricant P.D., Rosenberger P.H., Jokl P., Ickovics J.R. Predictors of short-term recovery differ from those of long-term outcome after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herbert R.D., Kasza J., Bo K. Analysis of randomised trials with long-term follow-up. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:48. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0499-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rongen J.J., Govers T.M., Buma P., et al. Arthroscopic meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tears reduces knee pain but is not cost-effective in a routine health care setting: A multi-center longitudinal observational study using data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthrit Cartil. 2018;26:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.02.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyd J.A., Gradisar I.M. Total knee arthroplasty after knee arthroscopy in patients older than 50 years. Orthopedics. 2016;39:e1041–e1044. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160719-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris I.A., Madan N.S., Naylor J.M., et al. Trends in knee arthroscopy and subsequent arthroplasty in an Australian population: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2013;14:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winter A.R., Collins J.E., Katz J.N. The likelihood of total knee arthroplasty following arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2017;18:408. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1765-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolano L.E., Grana W.A. Isolated arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: Functional radiographic evaluation at five years. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:432–437. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paradowski P.T., Englund M., Lohmander L.S., Roos E.M. The effect of patient characteristics on variability in pain and function over two years in early knee osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:59. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arthroscopy Association of Canada. Wong I., Hiemstra L., et al. Position statement of the Arthroscopy Association of Canada (AAC) concerning arthroscopy of the knee joint, September 2017. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6 doi: 10.1177/2325967118756597. 2325967118756597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller T. AAOS Now; 2018. Knee arthroscopy and osteoarthritis: The numbers rarely add up to 29880. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sofu H., Oner A., Camurcu Y., et al. Predictors of the clinical outcome after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for acute trauma-related symptomatic medial meniscal tear in patients more than 60 years of age. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:1125–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messner K., Fahlgren A., Persliden J., Andersson B.M. Radiographic joint space narrowing and histologic changes in a rabbit meniscectomy model of early knee osteoarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:151–160. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arno S., Hadley S., Campbell K.A., et al. The effect of arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy on tibiofemoral stability. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:73–79. doi: 10.1177/0363546512464482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edd S.N., Netravali N.A., Favre J., et al. Alterations in knee kinematics after partial medial meniscectomy are activity dependent. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1399–1407. doi: 10.1177/0363546515577360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall M., Wrigley T.V., Metcalf B.R., et al. Knee biomechanics during jogging after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: A longitudinal study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:1872–1880. doi: 10.1177/0363546517698934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee B.S., Bin S.I., Kim J.M., et al. Partial meniscectomy for degenerative medial meniscal root tears shows favorable outcomes in well-aligned, nonarthritic knees. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:606–611. doi: 10.1177/0363546518819225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhatia S., LaPrade C.M., Ellman M.B., LaPrade R.F. Meniscal root tears: significance, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:3016–3030. doi: 10.1177/0363546514524162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LaPrade C.M., Jansson K.S., Dornan G., et al. Altered tibiofemoral contact mechanics due to lateral meniscus posterior horn root avulsions and radial tears can be restored with in situ pull-out suture repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:471–479. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faucett S.C., Geisler B.P., Chahla J., et al. Meniscus root repair vs meniscectomy or nonoperative management to prevent knee osteoarthritis after medial meniscus root tears: clinical and economic effectiveness. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:762–769. doi: 10.1177/0363546518755754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krych A.J., Johnson N.R., Mohan R., et al. Partial meniscectomy provides no benefit for symptomatic degenerative medial meniscus posterior root tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:1117–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.