Abstract

Maturation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) across the first few years of life is thought to underlie the emergence of inhibitory control (IC) abilities, which may play an important role in children’s early academic success. In this growth curve modeling study (N = 364), we assessed developmental change in children’s resting-state electroencephalogram (EEG) activity (6–9 Hz ‘alpha’ power) from 10 months to 4 years and examined whether the initial levels or amount of change in frontal alpha power were associated with children’s IC at age 4 and indirectly academic skills at age 6. Results indicated that greater increases in frontal alpha power across the study period were associated with better IC, and indirectly with better performance on Woodcock-Johnson tests of reading and math achievement at age 6. Similar associations between change in EEG and age 4 vocabulary were observed but did not mediate an association with academic skills. Similar analyses with posterior alpha power showed no associations with IC. Findings underscore the significance of frontal lobe maturation from infancy to early childhood for children’s intellectual development.

Keywords: Frontal lobe, Executive function, Inhibitory control, EEG, Brain development, Academic achievement

1. Introduction

Higher-order cognitive skills associated with the prefrontal cortex (PFC) develop rapidly in the preschool period (Carlson, 2005) and may play an important role in children’s early academic success (Blair & Diamond, 2008). Inhibitory control (IC), the ability to suppress or temporarily withhold inappropriate behavior, is generally important for responding in situations when automatic or otherwise dominant response tendencies are inappropriate (Diamond, 2013). IC is thought to be particularly important for children as they transition to formal schooling (Blair & Raver, 2015; Morrison, Ponitz, & McClelland, 2010), and individual differences in preschool IC have been consistently associated with better academic achievement and learning-related outcomes (Allan, Hume, Allan, Farrington, & Lonigan, 2014; McClelland et al., 2014). Thus, understanding how IC develops, and identifying factors that contribute to individual differences in preschool, is critical for academic success.

Although environmental factors (e.g., caregiving) likely contribute to variation in preschoolers’ IC or general executive functioning (Cuevas et al., 2014; Hughes & Devine, 2019; Sulik, Blair, Mills-Koonce, Berry, & Greenberg, 2015), research with human infants and non-human primates suggests that IC is dependent on the functional integrity of the PFC (Diamond & Goldman-Rakic, 1989). Though rudimentary forms of children’s IC are first observable late in the first year, synaptic density in the human PFC is thought to be greatest around 3.5 or 4 years of age (Huttenlocher & Dabholkar, 1997), a time when children are able to suppress or delay behavior in accordance with rules and verbal instructions (Carlson, 2005; Hughes, 1998;Jones, Rothbart, & Posner, 2003). Thus, this work underscores that maturational changes in the PFC from infancy through preschool may contribute to individual differences in IC (Diamond, 2002), and subsequently, later academic success. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate whether developmental changes in resting-state EEG (electroencephalography) activity, thought to reflect frontal cortical maturity, across the infant and preschool years were associated with children’s IC at age 4 and subsequently academic skills at age 6.

1.1. Frontal alpha power and inhibitory control

EEG activity reflects a summation of postsynaptic potentials generated from multiple groups of cortical neurons firing in synchrony (Davidson, Jackson, & Larson, 2000). While not a direct measure of neural activity, it does provide a window into the underlying function and organization of the brain (Buzsáki, Anastassiou, & Koch, 2012; Pizzagalli, 2007). EEG is composed into distinct rhythms and is estimated in different frequency ranges (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma), which are associated with different kinds of perceptual, cognitive, and affective processes (Cuevas & Bell, in press). However, resting-state EEG alpha power, the focus of this study, is of considerable interest to developmental scientists (Anderson & Perone, 2018; Camacho, Qui-ñones-Camacho, & Perlman, 2020) given its association with the inhibition or suppression of task-irrelevant cortical processes (Klimesch, 2012). Although empirical work has shown greater baseline-to-task increases in frontal alpha power are associated with better IC task performance (Bell, 2001; Watson & Bell, 2013; Wolfe & Bell, 2007), individual differences in resting frontal alpha power are also associated with greater IC. For instance, 8-month-olds who tolerated longer delays on Piaget’s A-not-B task, an early measure of IC and working memory (Diamond, 1985; Holmboe, Bonneville-Roussy, Csibra, & Johnson, 2018; Holmboe, Fearon, Csibra, Tucker, & Johnson, 2008), exhibited larger frontal EEG alpha power values at rest than infants who performed poorly on the task (Bell & Fox, 1997). Similarly, 4.5-year-olds who succeeded on the Day-Night Stroop task exhibited larger frontal EEG alpha power values at rest compared to children who did not (Wolfe & Bell, 2004). Although not specific to the frontal region, greater resting alpha power values have been positively associated with EF task performance in 8-year-olds (Wade, Fox, Zeanah, & Nelson, 2019) and children with ADHD (a disorder characterized by IC deficits) have reduced EEG power values in the alpha band compared to typically-developing children (Barry, Clarke, & Johnstone, 2003; Clarke, Barry, McCarthy, & Selikowitz, 2011). Thus, like other physiological measures thought to provide an index of regulatory capacity (e.g., respiratory sinus arrythmia), the resting level of frontal alpha power may reflect children’s biological capacity for IC.

Resting frontal alpha power values are also considered indicative of brain maturation (Bell & Fox, 1994; Bell, 1998). In a seminal longitudinal study, it was found that children’s resting EEG alpha power values increased on average from 10 to 51 months of age (Marshall, Bar-Haim, & Fox, 2002). Additionally, Perone, Palanisamy, and Carlson (2018) reported age-related increases in 3- to 5-year-old children’s resting frontal alpha power values (relative to total power) during this developmental period (although a similar pattern was observed at posterior scalp sites). Developmental increases in EEG power, however, were not observed in other frequency ranges (theta, beta, gamma). Monthly increases in resting frontal alpha power towards the end of the first year have been positively associated with IC in infants (Bell & Fox, 1992). However, no study has investigated whether changes in resting frontal alpha power from infancy to preschool are associated with IC in preschool. Thus, more longitudinal work is needed to understand whether the foundational neurobiological components of IC in preschool are already present in infancy and whether maturational growth in the PFC across the toddler years also contributes to individual differences in preschool IC.

1.2. Inhibitory control and academic skills

Investigation into the neurobiological underpinnings of IC in preschool is crucial because IC at this time may help children transition to the academic environment (Blair, 2002). IC is thought to be especially important for math learning (Blair, Knipe, & Gamson, 2008). According to the interference hypothesis, for instance, learning and using more advanced math strategies and concepts requires the inhibition of previously learned, less advanced ones (Laski & Dulaney, 2015). There is much empirical support for the role of IC in children’s early math achievement (Allan et al., 2014; Blair & Razza, 2007; Bull, Espy, & Wiebe, 2008; Bull & Lee, 2014; Clark et al., 2010, 2013; Espy et al., 2004; McClelland et al., 2007).

Associations between IC and reading achievement, however, have been much less consistent. In one study with a low-income sample, a composite measure of EF predicted fall to spring change in both reading and math performance across preschool and continued to predict both aspects of academic ability in kindergarten (Welsh, Nix, Blair, Bierman, & Nelson, 2010). Similarly, in a different low-income sample, performance on a single IC task (head-to-toes) predicted fall to spring change in preschoolers’ reading and math ability (McClelland et al., 2007). Blair and The Family Life Project Investigators (2015) reported, however, that significant links between preschool IC and kindergarten reading performance were completely reduced by the inclusion of ‘cognitive covariates’ such as vocabulary; in contrast, links between IC and math were only modestly attenuated by this.

In assessing the relations between preschool IC and early academic skills, controlling for children’s verbal ability is crucial because IC is often positively correlated with verbal ability in preschoolers (Carlson & Moses, 2001; Wolfe & Bell, 2004, 2007). Wolfe and Bell (2004), for instance, reported that children’s receptive vocabulary, along with resting frontal alpha power, together accounted for more than 90% of the variance in 4.5-year-olds’ IC task performance. In a longitudinal study using a cross-lagged panel design, children’s vocabulary at 30 and 36 months was predictive of their IC task performance at 36 and 42 months (respectively), controlling for earlier task performance (Petersen, Bates, & Staples, 2015). Further, Cozzani, Usai, and Zanobini (2013) found that the ability to inhibit prepotent responses was closely associated with the ability to formulate sentences in young children between 26 and 31 months, controlling for age. Thus, because the development of IC in preschool may be somewhat interconnected with language competence, and because verbal ability may contribute to academic performance independently of IC, including verbal ability as a covariate in the present study is important.

1.3. Current study

The larger longitudinal study from which these data were drawn was designed to investigate the role of psychobiological processes in cognitive and emotional development. We had three specific aims for the current study. The first aim was to assess the general pattern of change in children’s resting frontal EEG alpha (6–9 Hz) power, a measure of frontal cortical maturity, from infancy to preschool. Based on theory and previous research (Marshall et al., 2002), a significant amount of positive change (i.e., growth) in this measure from 10 months to 4 years was expected.

The second aim of the study was to assess whether the initial levels of frontal alpha power or amount of change in frontal alpha power from infancy to preschool were associated with children’s IC in preschool. Based on theory and previous research (Diamond, 2002; Wolfe & Bell, 2004), we expected that change in children’s frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years would be positively associated with their IC at age 4 over and above initial levels.

The final aim of the study was to assess whether children’s IC in preschool was a mediating mechanism linking the initial level or amount of change in resting frontal alpha power from infancy to preschool to their early academic skills in reading and mathematics. Based on theory and previous research (Allan et al., 2014; Blair et al., 2008), we expected that children’s IC at age 4 would be positively associated with their math and reading achievement at age 6. Additionally, positive indirect effects from the initial levels and amount of change in frontal alpha power to both 6-year outcomes (through IC) were expected.

Because children’s IC and verbal ability are often positively correlated in young children (e.g., Carlson & Moses, 2001), and because frontal lobe maturation may also contribute to early advances in language, to ensure that any significant associations between latent growth factors, IC, and academic skills were not attributable to children’s general language ability, we controlled for children’s vocabulary (age 2, age 4, age 6) in these analyses. Parallel growth models were conducted using posterior (parietal, occipital) alpha power values in order to examine region specificity.

To our knowledge, no previous study has examined developmental changes in resting-state EEG activity from infancy to preschool as predictors of individual differences in preschool behavior. Although measures of EEG power may not capture all aspects of brain development processes that are important (e.g., connectivity), because previous studies have reported positive, concurrent associations between resting frontal EEG alpha power and IC in both infants and preschoolers (Bell & Fox, 1997; Bell, 2001; Wolfe & Bell, 2004), examining these longitudinal associations builds meaningfully on previous work.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Children were part of a longitudinal investigation of cognition-emotion relations. The full sample was recruited at 5 months, with 5 added at 10 months (N = 410), from two research locations (Blacksburg, VA; Greensboro, NC); approximately half was recruited from each location. Most (73%) children were White and non-Hispanic; half (49%) were male; 69% had at least one parent with a 4-year college degree (48% had both). Children visited the research laboratory at 10 months, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, and 6 years of age. Three-hundred sixty-eight participated at 10 months (M = 10.30, SD = 0.37); 346 participated at 2 years (M = 2.08, SD = 0.08); 318 participated at 3 years (M = 3.10, SD =0.11); 300 participated at 4 years (M = 4.09, SD = 0.09), and 231 participated at 6 years (M = 6.59, SD = 0.38). Originally recruited as three cohorts, one cohort (approximately 25% of the larger study) was 3 years older than the other two cohorts and did not have a 6-year lab visit. Among children who participated at age 6, most were entering or already in 1st grade (70%) or kindergarten (27%).

Participants were included in the current study if they had any available data (for predictor variables) and were typically developing (N = 364). Of the 410, 46 were excluded: 17 were born prematurely or had low birthweight; 24 did not return to the lab after 5 months; 5 were further excluded due to atypical developmental status documented at age 4 (e.g., autism). Participants excluded from the sample were more likely to be non-White or Hispanic, t(53.5) = 3.31, p < .01, and to have less educated parents, t(55.77) = −3.30, p < .01, than those included. Excluded participants were also rated as more negative in temperament, t(28.17) = 2.70, p = .01, but did not differ significantly in terms of soothability, t(24.89) = −2.00, p > .05, or sex, t(56.76) = 0.17, p = .87.

2.2. Procedures

Data were collected at both research locations using identical protocols that were approved by their respective university institutional review boards (IRB). Research assistants from both locations were trained by the project’s Principal Investigator on behavioral and electrophysiological data collection and scoring. To ensure data were collected and analyzed identically across sites, the Blacksburg site periodically viewed DVDs and electrophysiology files collected by the Greensboro site and provided reliability coding for behavioral data collected by the Greensboro site.

Upon arrival to the laboratory at each visit, families were greeted by a research assistant who fully explained the study procedures and obtained signed consent from mothers. After a brief warm-up period, children were fitted with EEG caps, and baseline physiology was collected. Subsequently, children participated in a variety of tasks assessing cognitive and emotional functioning while mothers completed questionnaires. Sessions were digitally recorded. Families were compensated $50 and children received a small gift at each visit.

2.3. Measures

Electroencephalography (EEG).

Baseline EEG was recorded at 10, 24, 36, and 48 months while children watched a brief video clip, a procedure commonly used with infants and young children because it limits gross motor movements (Bell & Cuevas, 2012; Najar & Brooker, 2017; Schmidt, 2008). Procedural differences in EEG data collection across ages were minimal and developmentally appropriate (see Anderson & Perone, 2018 for a discussion). At the 10-month visit, infants were seated on mothers’ laps and shown a brief (M = 45 s) clip from Sesame Street (Cecile, Up Down, In Out, Over Under). At the age 2 visit, children were shown a clip from the Disney film Finding Nemo (sea turtles riding the Eastern Australian Current; M2 = 67 s) and at the age 3 and age 4 visits they were shown a clip of the Disney film Lion King (M3 = 110 s; M4 = 113 s) while seated at a small table (or a high-chair for the toddler visit). Mothers were seated nearby but did not interact with their children.

EEG recordings were made from 16 left and right scalp sites (frontal pole [Fp1, Fp2], medial frontal [F3, F4], lateral frontal [F7, F8], central [C3, C4], temporal [T7, T8], medial parietal [P3, P4], lateral parietal [P7, P8], and occipital [O1, O2]). All electrode sites were referenced to Cz during recording. Based on publication guidelines for EEG studies (Keil et al., 2014), we report the following details. EEG was recorded using a stretch cap (Electro-Cap International, Inc.) with electrodes in the 10/20 system pattern (Jasper, 1958). After the cap was placed on the head, a small amount of abrasive gel was placed into each recording site and the scalp was gently rubbed; conductive gel was then placed into each site. Electrode impedances were measured and accepted if they were below 20 K ohms.

The electrical activity from each lead was amplified using separate James Long Company Bioamps (Caroga Lake, NY). During data collection, the high-pass filter was a single pole RC filter with a 0.1-Hz cut-off (3 dB or half-power point) and 6 dB per octave roll-off. The low-pass filter was a two-pole Butterworth type with a 100 Hz cut-off (3 dB or half-power point) and 12-dB octave roll-off. Activity for each lead was displayed on the monitor of an acquisition computer. The EEG signal was digitized online at 512 samples per second for each channel to eliminate the effects of aliasing. The acquisition software was Snapshot-Snapstream (HEM Data Corp.) and the raw data were stored for later analyses. Prior to data collection, spectral analysis of the calibration signal in the 9–11 Hz frequency band was accomplished.

EEG data were later examined and analyzed using EEG Analysis System software developed by James Long Company. First, the data were re-referenced to an average reference configuration (Lehmann, 1987); this weighted all the electrode sites equally and eliminated the need for a non-cephalic reference. As the number of electrodes is increased and the coverage of the whole brain is approachable, it is increasingly believed that the average potential over all the electrodes provides a virtual zero-potential point (Bertrand, Perrin, & Pernier, 1985). The average reference configuration does require that a sufficient number of electrodes be sampled and that these electrodes be evenly distributed across the scalp. Currently, there is no agreement concerning the appropriate number of electrodes (Davidson et al., 2000; Luck, 2005), but the 10/20 configuration does satisfy the requirement of even scalp distribution.

EEG data were artifact scored for eye movements using a peak-to-peak criterion of 100 uV or greater, and for gross motor movements using a peak-to-peak criterion of 200 uV or greater. If artifact was present in one channel, then data in all channels were excluded. No artifact correction procedures were used. The mean number of artifact-free DFT windows per minute was 56 at 10 months (SD = 29), 73 at 24 months (SD = 24), 82 at 36 months (SD = 20), and 78 at 48 months (SD = 23). Subsequently, the artifact-free EEG data were analyzed with a discrete Fourier transform (DFT) using a Hanning window of 1 s width and 50% overlap. EEG power was computed for the 6–9 Hz alpha frequency band, which is the dominant band from 5 to 51 months (Marshall et al., 2002). In addition, the 6–9 Hz alpha band is associated with executive function task performance (including inhibitory control tasks) during infancy and early childhood (e.g., Bell & Fox, 1992; MacNeill, Ram, Bell, Fox, & Pérez, 2018; Swingler, Willoughby, & Calkins, 2011; Wolfe & Bell, 2004, 2007). Power was expressed as mean square microvolts and the data were transformed using the natural log (ln) to normalize the distribution. Power values at frontal scalp sites (Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8) were averaged to yield a composite at each age, which is commonly done to achieve a general indicator of EEG over the broader frontal scalp area (e. g., Bar-Haim et al., 2002). Most (85%) children had at least 2 time points of data, and nearly half (46%) were not missing any EEG data (see Table 1a).

Table 1a.

Reasons for Missing EEG Data by Timepoint.

| 10m | 2y | 3y | 4y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No lab visit | 18 | 59 | 84 | 110 |

| Refused cap | 1 | 35 | 21 | 18 |

| Equipment failure/corrupt data files | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Poor signal quality/missing >4 electrodes | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Too much artifact | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Different baseline procedure | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: Too much artifact was defined as <10 DFT windows.

Inhibitory Control.

At age 4, children’s IC was observed from a battery of tasks and from the experimenter’s report of their behavior at the lab visit. Due to a planned difference in protocols across cohorts, only children at the Greensboro site were administered one of the experimental tasks (Three Pegs). Additionally, children from the older cohort (26% of the sample) at the Blacksburg site were not administered the experimenter-report measure because it was not yet part of the study protocol. Aside from that, however, missingness was low (see Table 1b) and most (70%) children had data for at least 1 measure (30% had data for all 4 measures).

Table 1b.

Reasons for Missing Inhibitory Control Data at Age 4.

| Simon Says | Day-Night | Three Pegs | PSRA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No lab visit | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 |

| Not yet in study protocol | 0 | 0 | 120 | 67 |

| Child fussy; task not administered | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Child refused task | 8 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Child could not understand rules | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Recording error | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Voided (maternal interference) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

Note: PSRA = Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment.

In the Simon Says Task (i.e., Bear/Dragon; Carlson, Moses, & Breton, 2002), children were instructed to obey the commands given by a ‘good/nice’ hand puppet (e.g., Touch your nose!) but to ignore the commands given by a ‘bad/grumpy’ puppet. Approximately 4 ‘go’ and 4 ‘no-go’ trials were administered in an alternating order. The proportion of correct ‘no-go’ trials was calculated and used in the analyses. Reliability scoring for this task was accomplished on 16% of the sample (ICC = 0.99).

In the Day-Night task (Gerstadt, Hong, & Diamond, 1994), children were instructed to say ‘day’ when shown a card depicting a moon and to say ‘night’ when shown a card depicting a sun. A minimum of two practice trials were given, followed by 16 test trials (half for each type) in a pseudorandom order. The proportion of correct trials was calculated and used in the analyses; points were not awarded if the child perseverated by saying the same word for each trial. Reliability scoring for this task was accomplished on 14% of the sample (ICC = 0.97).

In the Three Pegs task (Balamore & Wozniak, 1984), children were given a wooden mallet and instructed to tap a set of colored pegs in non-canonical order; to succeed, they needed to inhibit the dominant tendency to tap the pegs in the order they were presented (i.e., from left to right). First, a pretest was given to ensure that children could distinguish between the colors (blue, green, yellow). Then, a series of trials were administered; to ‘pass’, children needed to tap the correct color sequence twice in a row. If the child tapped correctly, a second (confirmation) trial was given. Children received at least two and as many as six trials depending on their pattern of responding. A proportional score (total correct/total trials) was calculated and used in the analyses.

Experimenters reported on children’s IC by completing the Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment (PSRA; Smith-Donald, Raver, Hayes, & Richardson, 2007). The PSRA contains 25 items that load onto two broad factors (Attention/Impulse Control, Positive Emotion). For each item, raters circle the number (0–3) that best describes the child’s behavior during the laboratory session. The Attention/Impulse Control factor was used for the current analyses and consists of 11 items (e.g., Has difficulty waiting between tasks; Lets examiner finish before starting task; Does not interrupt) and had an internal consistency of 0.91 in the current sample. Completion of the PSRA was accomplished by the experimenter who interacted with the child and within 30 min of the family leaving.

Academic Skills.

Children’s academic skills were assessed at age 6 using the Woodcock-Johnson (WJ) Tests of Achievement (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). To assess math performance, the Math Fluency, Applied Problems, and Calculation subtests were administered. To assess reading performance, the Reading Fluency, Letter-Word Identification, and Passage Comprehension subtests were administered. Age-normed scores for each subtest were calculated, averaged, and used in the analyses. Because the 6-year lab visit was not part of the study protocol for children who were part of an earlier cohort, a quarter of the sample was not administered these measures. However, most (70%) children from the other cohorts had available data for both measures.

Verbal Ability.

Children’s verbal ability was assessed at ages 2, 4, and 6 using questionnaire and observed measures of vocabulary.

At the 2-year visit, mothers completed the ‘Words and Sentences’ form from the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI; Fenson et al., 1992), a checklist of common words and phrases designed for use with children 16 to 30 months. Mothers indicated their toddlers’ production of each item on the inventory (e.g., yum-yum, tiger, need to) and reported on their grammatical ability. The total vocabulary score was used in the analyses; higher scores indicated a larger breadth of vocabulary.

At the 4- and 6-year visits, children’s receptive vocabulary was assessed with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 1997), a standardized measure of receptive language ability. Children were asked to select one of four pictures displayed on an easel that best depicted a word (e.g., spoon, jumping) read aloud by an experimenter. Test items were grouped into 12-item sets that increased in difficulty; testing stopped when children answered incorrectly eight or more times within a set. Following manual guidelines, the raw score was calculated by subtracting the number of errors from the ceiling item; higher scores indicated a larger vocabulary. A standardized score was then calculated based on children’s age in months.

3. Results

3.1. Data analysis strategy

To address the first aim of the study, a series of nested growth curve models were fit to the repeated measures EEG data at 10, 24, 36, and 48 months. By modeling developmental EEG changes in a growth curve, questions regarding the average pattern of change in children’s frontal alpha power as well as how individual differences in the initial levels and amount of change were associated with their IC at age 4 could be addressed (Grimm, Ram, & Estabrook, 2017).

To address the second aim, EEG growth factors (intercept, slope) were modeled as predictors of IC at age 4. As a latent (i.e., unobservable) construct, children’s IC was estimated as a latent factor from their performance across the battery of experimental tasks and questionnaire measure, which allows for shared error attributable to the measure to be removed from parameter estimates (Muthén & Curran, 1997). Although this approach cannot resolve issues of missing data, because half the sample was administered all four IC measures, and because all children were administered language measures, it allowed us to make use of all available data across cohorts.

To address the third aim, children’s observed math and reading performance were entered into the structural model as dependent (manifest) variables and their direct associations with IC and latent growth factors were examined. Subsequently, indirect effects from both latent growth factors to both 6-year outcomes (through IC) were examined using bias-corrected bootstrapping (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Across aims, parallel models based on posterior (P3, P4, P7, P8, O1, O2) EEG power values were conducted to determine if the anticipated results were specific to the frontal region.

3.2. Preliminary analyses

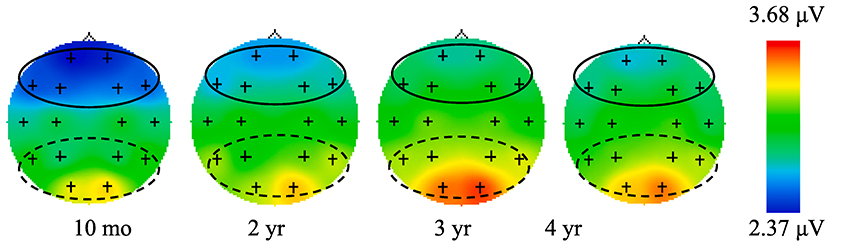

Preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS (v. 25) and involved creating composite EEG variables, assessing the normality of distributions, and examining the bivariate correlations among study variables. First, a frontal EEG power composite was calculated at each age by averaging the frontal (Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8) power values, which showed strong positive correlations (r’s = 0.65–0.85). These four composites (one for each age) served as indicators of the latent growth factors in the measurement model. Between one and two data points were winsorized at each time point. Fig. 1 shows topographic maps of EEG power at 6–9 Hz at each electrode site.

Fig. 1.

Topographic Maps for 6–9 Hz EEG Power Across Age. Note: The frontal electrodes used to create a frontal EEG composite of interest are highlighted with a solid line. The posterior electrodes used to create the EEG composite for the control analyses are highlighted with a dashed line.

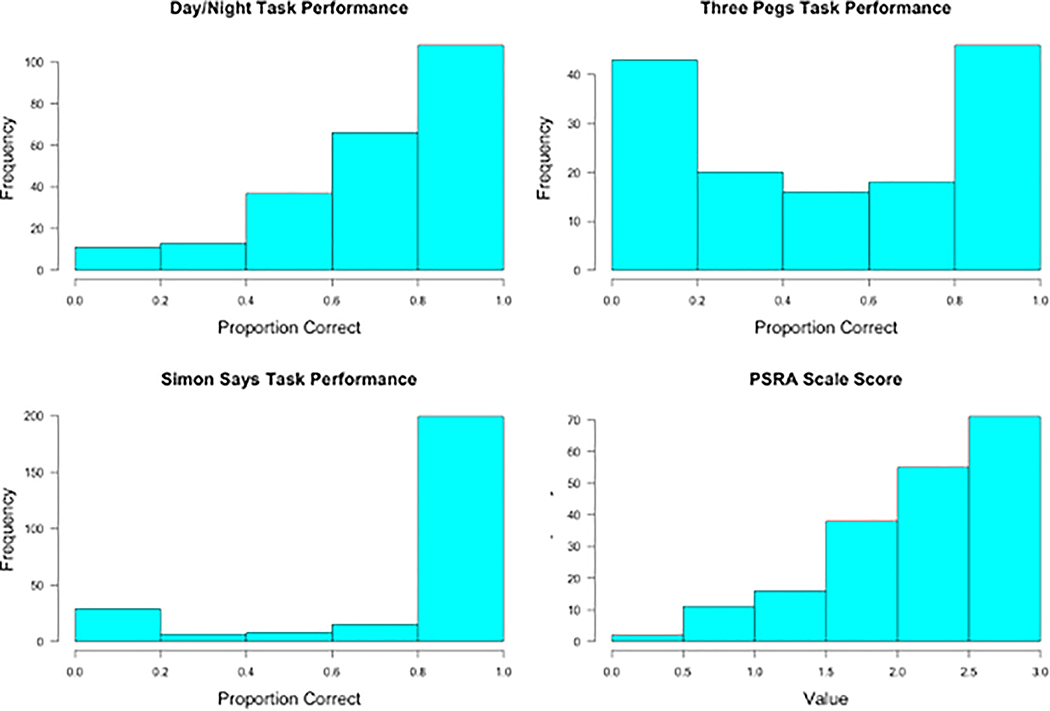

Subsequently, descriptive properties and bivariate correlations among IC variables were examined. As depicted in Fig. 2, performance on the Simon Says task was negatively skewed: 10 percent of children failed all ‘no-go’ trials; 13 percent failed some trials; 77 percent were correct on all test trials. For the Day-Night task, scores were more normally distributed: 2 percent of children failed all trials; 43 percent were correct on some trials; 44 percent were correct on most trials; 11 percent received a perfect score. For the Three Pegs task, 28 percent of children tapped the pegs incorrectly on all trials; 37 percent were correct on some or most trials; 35 percent were correct on all trials. PSRA scores were somewhat negatively skewed but evenly distributed: 7% had scores less than or equal to 1, 30% had scores between 1 and 2, 56% had scores between 2 and 3, and 7% had scores equal to 3. As depicted in Table 2, performance on the IC tasks were positively correlated with each other and with the PSRA measure.

Fig. 2.

Histogram Plots for Inhibitory Control Variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive Properties and Bivariate Correlations among Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Frontal EEG power (10 m) | **0.40 | **0.39 | **0.39 | *0.12 | *−0.17 | −−0.05 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.10 | |

| 2. | Frontal EEG power (2y) | **0.56 | **0.53 | **0.20 | −0.10 | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | *−0.20 | *−0.19 | ||

| 3. | Frontal EEG power (3y) | **0.78 | †0.12 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.12 | −0.06 | −0.08 | |||

| 4. | Frontal EEG power (4y) | *0.14 | 0.04 | *0.16 | 0.12 | *0.17 | **0.18 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | ||||

| 5. | Vocabulary (2y) | **0.20 | −0.06 | **0.26 | *0.18 | **0.29 | **0.36 | 0.09 | 0.10 | |||||

| 6. | Simon Says (4y) | †0.13 | **0.30 | **0.28 | **0.27 | **0.36 | **0.23 | **0.31 | ||||||

| 7. | Day–Night (4y) | −0.03 | *0.20 | †0.13 | −0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |||||||

| 8. | Three Pegs (4y) | **0.36 | **0.53 | **0.39 | **0.31 | **0.26 | ||||||||

| 9. | PSRA (4y) | **0.26 | **0.39 | **0.22 | **0.29 | |||||||||

| 10. | Vocabulary (4y) | **0.64 | **0.22 | *0.19 | ||||||||||

| 11. | Vocabulary (6y) | **0.28 | **0.30 | |||||||||||

| 12. | WJ Reading (6y) | **0.73 | ||||||||||||

| 13. | WJ Math (6y) | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 2.50 | 2.74 | 2.92 | 2.86 | 312.45 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.53 | 2.20 | 72.77 | 75.55 | −0.11 | 0.00 | |

| SD | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 170.67 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.63 | 24.10 | 21.10 | 1.00 | 0.91 | |

| Range | 2.52 | 2.61 | 2.45 | 2.14 | 678 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.91 | 94.90 | 87.70 | 4.58 | 5.55 | |

| Skew | 0.10 | −0.40 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.16 | −1.93 | −1.05 | −0.10 | −0.91 | −0.93 | −1.18 | 0.37 | 0.35 | |

| N | 330 | 267 | 251 | 231 | 315 | 245 | 223 | 131 | 186 | 249 | 182 | 180 | 181 | |

Note:

p < .01

p < .05.

Frontal EEG power is alpha frequency band (6–9 Hz) averaged across Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8 electrodes. Variables 6 through 9 are IC measures. PSRA = Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment; WJ = Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement.

Descriptive properties and bivariate correlations among all study variables are displayed in Table 2. The frontal EEG power composites at each age were normally distributed and positively correlated with one another. The four IC variables were mostly positively correlated with one another, and the WJ variables were strongly positively correlated (R = 0.73). Vocabulary measures were positively correlated with one another and with many other study variables; age 2 vocabulary was positively correlated with EEG power at each age. Age 4 EEG was positively correlated with two IC variables (PSRA, Day-Night) and with age 4 vocabulary.

3.3. Analyses addressing research questions

Analyses were conducted in Mplus (v.8; Muthén & Muthén, 2012) and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to handle missing data. For clarity, unstandardized path estimates were depicted in-text and standardized estimates were depicted in figures; p-values from the standardized Mplus output were reported in both locations.

Aim 1.

The first aim of the study was to investigate the general pattern of change in children’s resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years. To do this, a series of nested growth curve models were conducted on the repeated measures EEG data and the fit of these models were examined and compared. Model fit was assessed by examining the comparative fit index (CFI; Marsh & Hau, 2007) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Cole & Maxwell, 2003). CFI values greater than 0.95 and RMSEA values less than or equal to 0.08 suggest good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Chi-square difference tests were conducted to determine which growth model fit the data best.

First, a ‘no growth’ model was conducted, in which the frontal EEG power composites from each timepoint were modeled as indicators of a single latent growth factor (intercept); all factor loadings were fixed to one. This model did not fit well: χ2(8) = 272.87, p < .00; RMSEA = 0.31 [0.28–0.34]; CFI = 0.21. Second, a linear growth model was conducted by adding a slope factor to the model; factor loadings for the 10-, 24-, 36, and 48-month EEG composites were set to 0, 0.368, 0.684, and 1, respectively. This model fit better but not well: χ2(5) = 81.11, p < .00; RMSEA = 0.21 [0.17–0.25]; CFI = 0.77. Third, a latent basis growth model was conducted by allowing the slope factor loadings for the 2- and 3-year EEG composites to be freely estimated; factor loadings for the 10-and 48-month EEG composites were still fixed to 0 and 1 (Grimm et al., 2017). This model fit very well: χ2(3) = 2.19, p = .53; RMSEA = 0.00 [0.00–0.08]; CFI = 1.0. Because the difference in chi square from the latent basis and no-growth model (χ2δ = 270.68) exceeded the critical value of 15.09, and because the difference in chi square from the latent basis and linear growth model (χ2 δ = 78.92) exceeded the critical value of 9.21, it was concluded that the latent basis growth model explained the data best.

Subsequently, the fixed and random effects for the latent basis growth model were examined. The means of the intercept and slope were both significantly different from zero (Intercept: M = 2.50, p < .01; Slope: M = 0.38, p < .01), indicating that children’s initial level of resting frontal alpha power was 2.50 and increased by 0.38 per unit of time on average. However, the factor loading for age 2 was 0.62, indicating that 62% of the total change in children’s resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years had occurred by the second timepoint. Additionally, the factor loading for age 3 was 1.10, indicating that children’s frontal alpha power values tended to be greatest at age 3. Thus, the average rate of change in children’s resting frontal alpha power was nonlinear, such that values increased from 10 months to 3 years but modestly declined from 3 to 4 years on average.

The intercept and slope factors from the latent basis growth model were not significantly correlated with one another, indicating that the amount of change in children’s frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years was not related to the initial levels. However, the variances of both factors were significant (Intercept = 0.09, p < .01; Slope = 0.08, p = .01), indicating that there was enough between-person variability in these parameters for them to serve as predictors of IC. Thus, to summarize, the latent basis model fit the repeated measures EEG data best and the average rate of change in children’s resting frontal alpha power was nonlinear, such that values increased from 10 months to 3 years but modestly declined from 3 to 4 years on average.

Aim 2.

The second aim of the study was to assess whether the initial levels of resting frontal alpha EEG power at 10 months or amount of change in resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years was associated with their IC at 4 years. To do this, IC was estimated as a latent factor from the four indicator variables and regressed onto the growth factors obtained from the latent basis model. Based on the pattern of correlations in Table 2, the PSRA score served as the base indicator for the IC factor. The measurement model fit well, χ2(34) = 55.81, p = .01; RMSEA = 0.04 [0.02–0.06]; CFI = 0.96, and all factor loadings were significant. Subsequently, IC was regressed onto the latent growth factors. Vocabulary (age 2, age 4) was controlled).

This model fit well: χ2(29) = 59.64, p < .01; RMSEA = 0.05 [0.03–0.07]; CFI = 0.94. The intercept (reflecting the initial level of frontal alpha power) was not significantly associated with IC but was positively correlated with vocabulary at 2 years (R = 0.19, p = .03). Age 2 vocabulary, in turn, was positively associated with IC at age 4 (B = 0.02, p < .01). The slope (reflecting the amount of change in frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years) was positively associated with IC (B = 0.40, p = .02) and age 4 vocabulary (B = 25.19, p = .01). Thus, children who exhibited higher overall levels of frontal alpha power across the study period tended to have more advanced language at age 2, which was positively associated with IC at age 4, but the intercept was not directly associated with IC. Rather, children who exhibited greater increases in resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years had greater IC at age 4. Thus, to summarize, results from the latent growth curve model indicated that change in resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years (but not initial levels) was positively associated with IC at age 4 over and above the association between EEG change and vocabulary.

Aim 3.

The final aim of the study was to investigate whether IC in preschool was a mediating mechanism linking the initial levels of resting frontal alpha power, or the amount of change in frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years, to children’s academic skills at age 6. To do this, we entered children’s WJ math and reading performance scores into the structural model as dependent variables and their direct associations with IC and latent growth factors were examined. Subsequently, indirect associations between EEG growth factors and academic skills (through IC) were examined with bias-corrected bootstrapping (1000 draws; MacKinnon et al., 2004). In this model, we also controlled for children’s vocabulary at age 6.

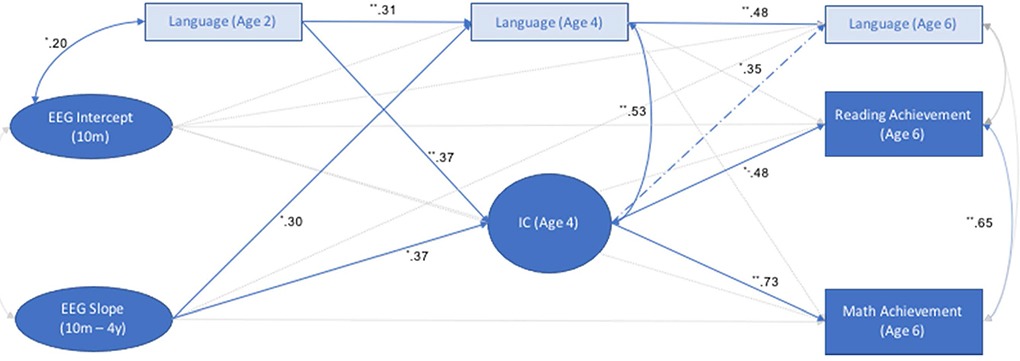

This model fit well: χ2(44) = 78.63, p = .00; RMSEA = 0.05 [0.03–0.06]; CFI = 0.96 (see Fig. 3). IC was positively associated with math (B = 1.90, p < .01) and reading performance (B = 1.36, p = .03), and marginally positively associated with vocabulary. In contrast, age 4 vocabulary was positively associated with age 6 vocabulary (B = 0.41, p < .01), but was not significantly associated with academic skills. Thus, IC at age 4 was positively associated with children’s academic skills at age 6, and this association was not explained by verbal ability.

Fig. 3.

Path Diagram Depicting Associations between EEG Growth Factors, Age 4 Inhibitory Control, and Age 6 Outcomes. Note: **p < .01, *p < .05. Dashed lines = p < .10. Intercept = initial level of resting frontal alpha power (centered at 10 months); Slope = change in frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years; Language was assessed with the MCDI at age 2 and with the PPVT at ages 4 and 6; IC = inhibitory control.

Direct associations between latent growth factors and age 6 outcomes were not significant. However, indirect effects from the slope to age 6 academic skills (through IC) were significant. Specifically, through an influence on IC, the slope was significantly positively related to WJ math performance (B = 0.93, 95% BC Bootstrap CI [0.17, 9.82]) and reading performance (B = 0.67, 95% BC Bootstrap CI [0.13, 6.95]) at age 6. Although significant associations between the slope and age 4 vocabulary were observed, because vocabulary was not associated with academic skills, these results suggest that IC is a mechanism through which frontal brain growth from infancy to preschool is associated with early academic skills. Thus, to summarize, indirect effects from the EEG slope to both WJ outcomes through IC at age 4 were significance, controlling for vocabulary, suggesting that IC is a mechanism through which children’s frontal brain maturation is associated with their early academic skills.

3.4. Control analyses

Given the pattern of correlations between age 4 EEG, vocabulary, and IC variables (see Table 2), we reversed the factor loadings for the latent basis model (such that 10-month EEG was fixed to −1 and 4-year EEG to 0) and subsequently reran the model addressing study aim 2. Model fit was identical, but the slope factor loading for age 3 EEG was not significant. However, the positive association between the slope and IC was still significant (B = 0.59, p = .035). Thus, our findings provide support for the role of change in frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years in the prediction of IC at 4 years.

Additionally, to assess whether the associations between EEG growth factors and IC were unique to the frontal region, parallel growth models were run using power values from homologous posterior scalp locations (P3, P4, P7, P8, O1, O2). As with the frontal power data, a latent basis model fit the posterior EEG power data best, and a similar pattern of change was observed from 10 months to 4 years. Similarly, the intercept from this model was positively correlated with vocabulary at age 2 (R = 0.23, p < .01) and the slope was positively associated with vocabulary at age 4 (B = 15.85, p = .02). However, the posterior EEG slope was not associated with IC (B = 0.19, p = .15). Thus, although growth in resting EEG alpha power at posterior scalp locations was also predictive of children’s language abilities, the associations between developmental EEG changes and IC were specific to the frontal regions.

4. Discussion

Maturation of the PFC across the first few years of life is thought to underlie the emergence of higher-order cognitive abilities in early childhood that are important for early academic success (Blair & Diamond, 2008; Diamond, 2002). Theoretical and empirical work has indicated that IC in preschool plays a particularly important role in this process (Blair & Razza, 2007; Blair et al., 2008; Wolfe & Bell, 2004). However, few studies have investigated the developmental process of PFC maturation in samples of typically developing children using noninvasive neuroimaging techniques. Thus, our understanding of how changes in PFC function across the first few years of life are associated with IC in preschool is limited.

The first specific aim of the current study was to characterize the general pattern of change in children’s resting frontal EEG (6–9 Hz ‘alpha’) power from infancy to preschool. Alpha power is considered indicative of brain maturation (Bell & Fox, 1994) and children’s resting frontal alpha power increases on average from 10 to 51 months (Marshall et al., 2002). Thus, a significant amount of positive change in children’s resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years was expected in our study.

Results indicated that a latent basis growth model, which allows for nonlinear change, fit our repeated measures EEG data best. On average, children’s resting frontal alpha power values increased from 10 months to 3 years before modestly declining. Thus, although a significant amount of positive change was observed, most of the change had occurred by age 2 and children did not exhibit much change on average from 3 to 4 years. This finding is not inconsistent with the small sample reported by Marshall et al. (2002; N = 29) because that study did not assess EEG between 24 and 48 months and thus could not account for any declining power values from 3 to 4 years. It is, however, consistent with Wolfe and Bell (2007), who reported that a group of 3.5-year-olds had larger resting frontal alpha power values than children who were either 4 or 4.5 years old. Thus, the nonlinear pattern of change in children’s frontal alpha power observed in this study is consistent with previous developmental EEG work.

It is also perhaps consistent with the idea that brain development is cyclical, characterized by periods of blooming and pruning of synapses (Greenough, Black, & Wallace, 1987). Indeed, although the data are not directly comparable, Huttenlocher and Dabholkar (1997) similarly found that synaptic density in the medial frontal gyrus peaked around 3.5 years before declining to adult levels. If age-related increases in alpha power are indicative of brain maturation (Bell & Fox, 1994), then age-related decreases in alpha power could be associated with synaptic pruning (Whitford et al., 2007). This interpretation is very speculative, and goes beyond the scope of the present study, but merits further investigation.

The second aim of our study was to assess whether the initial levels or amount of change in children’s resting frontal alpha power from infancy to preschool were associated with their IC in preschool. Resting frontal alpha power is positively associated with IC in both infants and preschoolers (Bell & Fox, 1992, 1997; Bell, 2001; Wolfe & Bell, 2004), and in one study, infant alpha was positively related to preschool EF (Kraybill & Bell, 2013). Rudimentary IC skills in infancy may serve as a foundation for more sophisticated IC skills that emerge in preschool. Thus, we were especially interested in whether developmental change in children’s frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years would be positively associated with their IC at 4 years over and above initial levels in infancy.

Results indicated that the slope, but not intercept, was positively associated with IC at age 4. That is, children with greater initial levels of frontal alpha power at 10 months did not necessarily have greater IC at 4 years. Rather, children who exhibited greater increases in frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years, reflecting greater PFC maturation during this time, had greater IC at 4 years. The pattern of factor loadings suggested that most of this change occurred between 10 and 36 months. However, the 4-year frontal EEG composite was positively correlated with IC measures. In the latent basis model, the slope indicates the average amount of change across the study period even if change is not completely linear on average (Grimm et al., 2017). Thus, although children exhibited modest declines in frontal alpha power from 3 to 4 years on average, possibly, children who exhibited continued increases in frontal alpha power from 3 to 4 years had greater IC at 4 years. It is not clear from this study whether changes in frontal alpha power in the earlier or later phase of the study period were more important for IC. However, results suggest that the neurobiological foundations of IC in preschool may begin in infancy but are not fully developed by 10 months.

Unexpectedly, both latent growth factors were positively associated with children’s verbal ability, which was included in the model as a control. Specifically, children who reportedly said more words at age 2 tended to have higher initial levels of resting frontal alpha power, and children who exhibited a greater amount of change in frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years tended to understand more words at age 4. Thus, although the significant association between the slope and IC observed in this study cannot be attributed to language, our findings do suggest that PFC maturation is important for language development, and that the development of IC in preschool may be somewhat interrelated and interconnected with that of language. While not the focus of this study, there is great theoretical interest in understanding role of language in the development of higher-order cognitive skills (Miller & Marcovitch, 2015; Müller, Jacques, Brocki, & Zelazo, 2009; Zelazo, 2004). Thus, future studies should more specifically investigate this component of the developmental process.

The third aim of our study was to investigate whether IC in preschool was a mediating mechanism linking the initial levels or amount of change in children’s resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years to their academic skills at age 6. Prior theoretical and empirical work has implicated IC in early math learning (Blair & Razza, 2007; Blair et al., 2008; Clark, Pritchard, & Woodward, 2010), but the relations between IC and reading achievement have been mixed (Blair, Ursache, Greenberg, & Vernon-Feagans, 2015). Thus, controlling for verbal ability, we were interested in whether children’s frontal brain growth from infancy to preschool would be associated with their math and reading performance at age 6 through an influence on IC at age 4.

As expected, children’s IC at age 4 was significantly positively associated with their math achievement at age 6 and was similarly predictive of reading. Thus, IC accounted for unique variance in academic skills not explained by verbal ability. We did not find significant direct effects from either latent growth factor to either age 6 outcome. However, indirect effects from the slope to both outcomes through IC at age 4 were significant. Specifically, children who exhibited greater increases in resting frontal alpha power from 10 months to 4 years tended to perform better on tests of early math and reading achievement than children who exhibited lesser increases in frontal alpha during this time, and better IC at age 4 may help to explain those associations. These findings add to a growing body of literature demonstrating the significance of IC for children’s early success in academics (Blair & Razza, 2007; Blair et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2010; McClelland et al., 2007) and further underscore the foundational role of biological processes in that regard.

4.1. Strengths, limitations, and future directions

Our study has several notable strengths, including a large, diverse sample with remarkably low attrition. Additionally, this is the first study to our knowledge, to examine developmental change in resting frontal alpha power across infancy and early childhood in relation to children’s emerging IC skills; our study is further innovative in the use of growth curve modeling to examine those changes. Traditional approaches to studying change (e.g., MANOVA) only consider mean-level change and treat differences among individual subjects as error variance. By modeling repeated measures of EEG power in a growth curve, we were able to assess the average pattern of change in this measure from infancy to preschool as well as how variability in the initial levels and amount of change were associated with IC (Grimm et al., 2017). Although the use of brain maturation as an explanation for cognitive change is problematic (Bell, 2015), our findings underscore the significance of children’s brain development during this time period (Diamond, 2002).

Our study, however, is not without its limitations. One limitation was the exclusive focus on EEG power in the alpha band. In contrast to alpha power, which increases with development, power in lower frequency ranges (e.g., delta, theta) is thought to decline with age (see Anderson & Perone, 2018). Some scholars have used power ratio measures (e.g., alpha/delta) to estimate children’s frontal cortical maturity (Schmidt & Poole, 2019), which could provide a more comprehensive picture than measures of frontal alpha power alone. An additional limitation was our exclusive focus on EEG power, which only provides information about the excitability of localized neuronal populations (Nunez, 1981). An important aspect of PFC maturity not measured in this study is connectivity. Indeed, scholars have maintained that neural networks important for self-regulation are rapidly forming across the first few years of life (Posner & Rothbart, 2007; Rothbart, Sheese, Rueda, & Posner, 2011). EEG coherence is a derived measure of EEG that reflects the temporal synchrony of activity at different scalp sites and may provide an index of connectivity between underlying cortical areas (Thatcher, 2012). Some studies have reported significant associations between developmental changes in frontal EEG coherence and children’s emerging EF skills (Broomell, Savla, & Bell, 2018; Whedon, Perry, Calkins, & Bell, 2016). Thus, in future work it may be useful to incorporate measures of both EEG power and coherence when investigating how developmental changes in the PFC are associated with IC in preschool.

It is also perhaps a limitation that we did not incorporate measures of early temperament, which are thought to serve an organizing role in the development of executive abilities that support self-regulation (Marshall, Fox, & Henderson, 2000). Considering that IC may ultimately play an important role in emotion regulation (Fox & Calkins, 2003), it is possible that early-emerging patterns of emotional reactivity could be related to IC development. Longitudinal studies are consistent with this view (Gagne & Goldsmith, 2011; Ursache, Blair, Stifter, & Voegtline, 2013), and recent work from our lab suggests that infant emotional reactivity may play a role in shaping the development of frontal brain activity (blinded). Thus, although the purpose of this study was to investigate the significance of frontal lobe maturation for children’s intellectual functioning, it is important to recognize that other intrinsic factors associated with temperament may contribute to this developmental process.

A final limitation of the study is that extrinsic influences on children’s IC or frontal EEG maturation were not examined. Caregiver characteristics (e.g., sensitivity, control), for instance, have been associated with IC in preschoolers (Cuevas et al., 2014;Moilanen, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner, & Wilson, 2010), and recent work suggests that PFC function may partially explain those associations (Swingler, Isbell, Zeytinoglu, Calkins, & Leerkes, 2018). Additionally, in a previous study with our sample, mothers’ positive affect during interactions with infants at 5 months was associated with greater resting frontal EEG alpha power at 10 and 24 months, as well as greater increases in frontal EEG alpha power during this time (Bernier et al., 2016) Thus, although the purpose of our study was to investigate the neurobiological foundations of IC, it is important to recognize that children’s brain development does not occur within a vacuum and may have been influenced by environmental factors associated with caregiving (Fox, Levitt, & Nelson, 2010; Swingler, Perry, & Calkins, 2015; Vanderwert, Marshall, Nelson, Zeanah, & Fox, 2010). Further, a variety of intervention programs have been shown to aid executive function development in young children (Blair & Diamond, 2008; Diamond & Lee, 2011). Findings from our study shed light on the underlying biological mechanisms that may help explain their effects.

In summary, findings from our study shed light on the normative course of children’s brain development and provide much-needed empirical support for the role of PFC maturation in the development of IC. Results specifically suggest that while the neurobiological foundations of IC begin in infancy, it is the maturational growth in the PFC across the toddler and early childhood years that contributes to individual differences in preschool IC performance. These individual differences in preschool IC, in turn, lead to varying outcomes on later measures of mathematics and reading achievement. Much additional longitudinal work is needed, however, to better understand the degree of individual variation in this developmental process and the role of children’s early caregiving experiences.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants (HD043057, HD049878) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) awarded to Martha Ann Bell. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the NIH. We are grateful to the families for their participation in our research. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Allan NP, Hume LE, Allan DM, Farrington AL, & Lonigan CJ (2014). Relations between inhibitory control and the development of academic skills in preschool and kindergarten: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2368–2379. 10.1037/a0037493.supp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AJ, & Perone S (2018). Developmental change in the resting state electroencephalogram: Insights into cognition and the brain. Brain and Cognition, 126, 40–52. 10.1016/j.bandc.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamore U, & Wozniak RH (1984). Speech-action coordination in young children. Developmental Psychology, 20, 850–858. 10.1037/0012-1649.20.5.850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA, Beck JM, West GM, Bhangoo RK, … Leibenluft E (2002). The emergence of childhood bipolar disorder: A prospective study from 4 months to 7 years of age. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 23, 431–450. 10.1016/S0193-3973(02)00127-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barry R, Clarke A, & Johnstone S (2003). A review of electrophysiology in attention-deficit =hyperactivity disorder: I. Qualitative and quantitative electroencephalography. Clinical Neurophysiology, 114, 171–183. 10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA (1998). Frontal lobe function during infancy: Implications for the development of cognition and attention In Richards JE (Ed.), Cognitive neuroscience of attention: A developmental perspective; cognitive neuroscience of attention: A developmental perspective (pp. 287–316, Chapter x, 452 Pages) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA (2001). Brain electrical activity associated with cognitive processing during a looking version of the A-not-B task. Infancy, 2, 311–330. 10.1207/S15327078IN0203_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA (2015). Bringing the field of infant cognition and perception toward a biopsychosocial perspective In Calkins SD (Ed.), Handbook of infant development: A biopsychosocial approach (pp. 27–37). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, & Cuevas K (2012). Using EEG to study cognitive development: Issues and practices. Journal of Cognition and Development, 13, 281–294. 10.1080/15248372.2012.691143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, & Fox NA (1992). The relations between frontal brain electrical activity and cognitive development during infancy. Child Development, 63, 1142–1163. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, & Fox NA (1994). Brain development over the 1st year of life: Relations between electroencephalographic frequency and coherence and cognitive and affective behaviors In Dawson G, & Fischer KW (Eds.), Human behavior and the developing brain (pp. 314–345). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, & Fox NA (1997). Individual differences in object permanence performance at 8 months: Locomotor experience and brain electrical activity. Developmental Psychobiology, 31, 287–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Calkins SD, & Bell MA (2016). Longitudinal associations between the quality of mother· infant interactions and brain development across infancy. Child Development, 87, 1159–1174. 10.1111/cdev.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand O, Perrin F, & Pernier J (1985). A theoretical justification of the average reference in topographic evoked potential studies. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 62, 462–464. 10.1016/0168-5597(85)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C (2002). School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. American Psychologist, 57(2), 111–127. 10.1037/0003-066X.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Diamond A (2008). Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 899–911. 10.1017/S0954579408000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Raver CC (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 711–731. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Razza RP (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78, 647–663. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Knipe H, & Gamson D (2008). Is there a role for executive functions in the development of mathematics ability? Mind, Brain, and Education, 2, 80–89. 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2008.00036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Ursache A, Greenberg M, & Vernon-Feagans L (2015). Multiple aspects of self-regulation uniquely predict mathematics but not letter–word knowledge in the early elementary grades. Developmental Psychology, 51, 459–472. 10.1037/a0038813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomell APR, Savla J, & Bell MA (2018). Infant electroencephalogram coherence and toddler inhibition are associated with social responsiveness at age 4. Infancy. 10.1111/infa.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull R, & Lee K (2014). Executive functioning and mathematics achievement. Child Development Perspectives, 8, 36–41. 10.1111/cdep.12059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bull R, Espy KA, & Wiebe SA (2008). Short-term memory, working memory, and executive functioning in preschoolers: Longitudinal predictors of mathematical achievement at age 7 years. Developmental Neuropsychology, 33, 205–228. 10.1080/87565640801982312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, & Koch C (2012). The origin of extracellular fields and currents—EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13, 407–420. 10.1038/nrn3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho MC, Quinones-Camacho LE, & Perlman SB (2020). Does the child brain rest?: An examination and interpretation of resting cognition in developmental cognitive neuroscience. NeuroImage, 116688 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SE (2005). Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28, 595–616. 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, & Moses LJ (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72, 1032–1053. 10.1111/1467-8624.00333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Moses LJ, & Breton C (2002). How specific is the relation between executive function and theory of mind? contributions of inhibitory control and working memory. Infant and Child Development, 11(2), 73–92. 10.1002/icd.298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AR, Barry R, McCarthy R, & Selikowitz M (2011). Correlation between EEG activity and behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Neurotherapy, 15, 193–199. 10.1080/10874208.2011.595295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CAC, Pritchard VE, & Woodward LJ (2010). Preschool executive functioning abilities predict early mathematics achievement. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1176–1191. 10.1037/a0019672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CAC, Sheffield TD, Wiebe SA, & Espy KA (2013). Longitudinal associations between executive control and developing mathematical competence in preschool boys and girls. Child Development, 84, 662–677. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, & Maxwell SE (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzani F, Usai MC, & Zanobini M (2013). Linguistic abilities and executive function in the third year of life. Rivista Di Psicolinguistica Applicata, 13(1), 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas K, Deater-Deckard K, Kim-Spoon J, Watson AJ, Morasch KC, & Bell MA (2014). What’s mom got to do with it? Contributions of maternal executive function and caregiving to the development of executive function across early childhood. Developmental Science, 17(2), 224–238. 10.1111/desc.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas K, & Bell MA (in press). EEG frequency development across infancy and childhood. To appear In Gable P, Miller M, & Bernat E (Eds.), Oxford handbook of human EEG frequency analysis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Jackson DC, & Larson CL (2000). Human electroencephalography In Cacioppo JT, Tassinary, & Berntson GG (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (2nd ed., pp. 27–52). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (1985). Development of the ability to use recall to guide action, as indicated by infants’ performance on A. Child Development, 56, 868–883. 10.2307/1130099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (2002). Normal development of prefrontal cortex from birth to young adulthood: Cognitive functions, anatomy, and biochemistry In Stuss DT, & Knight RT (Eds.), Principles of frontal lobe function (pp. 466–503). New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780195134971.003.0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, & Goldman-Rakic PS (1989). Comparison of human infants and rhesus monkeys on Piaget’s A task: Evidence for dependence on dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Experimental Brain Research, 74, 24–40. 10.1111/infa.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, & Lee K (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333, 959–964. 10.1126/science.1204529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn LM (1997). Peabody picture vocabulary test—III. Circle Pines, MN: AGS. [Google Scholar]

- Espy KA, McDiarmid MM, Cwik MF, Stalets MM, Hamby A, & Senn TE (2004). The contribution of executive functions to emergent mathematic skills in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 26, 465–486. 10.1207/s15326942dn2601_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung JP, … Reilly JS (1992). MacArthur communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Fox SE, Levitt P, & Nelson CA (2010). How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Development, 81, 28–40. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, & Calkins SD (2003). The development of self-control of emotion: Intrinsic and extrinsic influences. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 7–26. 10.1023/A:1023622324898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JR, & Goldsmith HH (2011). A longitudinal analysis of anger and inhibitory control in twins from 12 to 36 months of age. Developmental Science, 14(1), 112–124. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstadt CL, Hong Y, & Diamond A (1994). The relationship between cognition and action: Performance of children 3 1/2–7 years old on a Stroop-like day-night test. Cognition, 53, 129–153. 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough WT, Black JE, & Wallace CS (1987). Experience and brain development. Child Development, 58, 539–559. 10.2307/1130197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Ram N, & Estabrook R (2017). Growth modeling: Structural equation and multilevel modeling approaches. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe K, Fearon RMP, Csibra G, Tucker LA, & Johnson MH (2008). FreezeFrame: A new infant inhibition task and its relation to frontal cortex tasks during infancy and early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 100, 89–114. 10.1016/j.jecp.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe K, Bonneville-Roussy A, Csibra G, & Johnson MH (2018). Longitudinal development of attention and inhibitory control during the first year of life. Developmental Science, 21, 1–14. 10.1111/desc.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C (1998). Executive function in preschoolers: Links with theory of mind and verbal ability. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(2), 233–253. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1998.tb00921.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, & Devine RT (2019). For better or for worse? Positive and negative parental influences on young children’s executive function. Child Development, 90, 593–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR, & Dabholkar AS (1997). Regional differences in synaptogenesis in the human cerebral cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 387, 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper HH (1958). The ten twenty-electrode system of the international federation. Electroencephalography Clinical Neurophysiology, 10, 371–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LB, Rothbart MK, & Posner MI (2003). Development of executive attention in preschool children. Developmental Science, 6(5), 498–504. 10.1111/1467-7687.00307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Debener S, Gratton G, Junghofer M, Kappenman ES, Luck SJ, & Yee CM (2014). Committee report: Publication guidelines and recommendations for studies using electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography. Psychophysiology, 51, 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W (2012). Alpha-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16, 606–617. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraybill JH, & Bell MA (2013). Infancy predictors of preschool and post-kindergarten executive function. Developmental Psychobiology, 55, 530–538. 10.1002/dev.21057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laski EV, & Dulaney A (2015). When prior knowledge interferes, inhibitory control matters for learning: The case of numerical magnitude representations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 1035–1050. 10.1037/edu0000034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann D (1987). Principles of spatial analysis In Gevins AS, & Remond A (Eds.), Handbook of electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. Methods of analysis of brain electrical and magnetic signals (Vol. 1, pp. 309–354). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ (2005). An introduction to the event-related potential technique. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence Limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill LA, Ram N, Bell MA, Fox NA, & Pérez EK (2018). Trajectories of infants’ biobehavioral development: Timing and rate of A-not-B performance gains and EEG maturation. Child Development, 89, 711–724. 10.1111/cdev.13022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, & Hau K (2007). Applications of latent-variable models in educational psychology: The need for methodological-substantive synergies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32, 151–170. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PJ, Bar-Haim Y, & Fox NA (2002). Development of the EEG from 5 months to 4 years of age. Clinical Neurophysiology, 113, 1199–1208. 10.1016/S1388-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PJ, Fox NA, & Henderson HA (2000). Temperament as an organizer of development. Infancy, 1, 239–244. 10.1207/S15327078IN0102_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Connor CM, Farris CL, Jewkes AM, & Morrison FJ (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 947–959. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Duncan R, Bowles RP, Acock AC, Miao A, & Pratt ME (2014). Predictors of early growth in academic achievement: The head-toes-knees-shoulders task. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SE, & Marcovitch S (2015). Examining executive function in the second year of life: Coherence, stability, and relations to joint attention and language. Developmental Psychology, 51, 101–114. 10.1037/a0038359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen KL, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, & Wilson M (2010). Predictors of longitudinal growth in inhibitory control in early childhood. Social Development, 19, 326–347. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison FJ, Ponitz CC, & McClelland MM (2010). Self-regulation and academic achievement in the transition to school In Calkins SD, & Bell MA (Eds.), Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 203–224). American Psychological Association 10.1037/12059-011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, Jacques S, Brocki K, & Zelazo PD (2009). The executive functions of language in preschool children In Winsler A, Fernyhough C, & Montero I (Eds.), Private speech, executive functioning, and the development of verbal self-regulation (pp. 53–68). Cambridge University Press 10.1017/CBO9780511581533.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, & Curran PJ (1997). General growth modeling of individual differences in experimental designs: A latent variable framework for analysis and power estimation. Psychological Methods, 2, 371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus: The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers—User’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL (1981). Electrical fields of the brain: The neurophysics of EEG. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Perone S, Palanisamy J, & Carlson SM (2018). Age-related change in brain rhythms from early to middle childhood: Links to executive function. Developmental Science, 21, 1–15. 10.1111/desc.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen IT, Bates JE, & Staples AD (2015). The role of language ability and self-regulation in the development of inattentive-hyperactive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 221–237. 10.1017/S0954579414000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA (2007). Electroencephalography and high-density electrophysiological source localization In Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, & Berntson GG (Eds.), Handbook of Psychophysiology (3rd ed, pp. 56–84). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, & Rothbart MK (2007). Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 1–23. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese BE, Rueda MR, & Posner MI (2011). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation in early life. Emotion Review, 3, 207–213. 10.1177/1754073910387943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]