Abstract

BACKGROUND

Liver fibrosis progressing to liver cirrhosis and hepatic carcinoma is very common and causes more than one million deaths annually. Fibrosis develops from recurrent liver injury but the molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Recently, the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway has been reported to contribute to fibrosis. Extracellular histones are ligands of TLR4 but their roles in liver fibrosis have not been investigated.

AIM

To investigate the roles and potential mechanisms of extracellular histones in liver fibrosis.

METHODS

In vitro, LX2 human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) were treated with histones in the presence or absence of non-anticoagulant heparin (NAHP) for neutralizing histones or TLR4-blocking antibody. The resultant cellular expression of collagen I was detected using western blotting and immunofluorescent staining. In vivo, the CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model was generated in male 6-week-old ICR mice and in TLR4 or MyD88 knockout and parental mice. Circulating histones were detected and the effect of NAHP was evaluated.

RESULTS

Extracellular histones strongly stimulated LX2 cells to produce collagen I. Histone-enhanced collagen expression was significantly reduced by NAHP and TLR4-blocking antibody. In CCl4-treated wild type mice, circulating histones were dramatically increased and maintained high levels during the duration of fibrosis-induction. Injection of NAHP not only reduced alanine aminotransferase and liver injury scores, but also significantly reduced fibrogenesis. Since the TLR4-blocking antibody reduced histone-enhanced collagen I production in HSC, the CCl4 model with TLR4 and MyD88 knockout mice was used to demonstrate the roles of the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. The levels of liver fibrosis were indeed significantly reduced in knockout mice compared to wild type parental mice.

CONCLUSION

Extracellular histones potentially enhance fibrogenesis via the TLR4–MyD88 signaling pathway and NAHP has therapeutic potential by detoxifying extracellular histones.

Keywords: Liver fibrosis, Extracellular histones, Non-anticoagulant heparin, TLR4, MyD88, CCl4

Core Tip: This study fills the gap between recurrent liver injury and liver fibrosis. When liver cells die, histones are released. High levels of extracellular histones not only cause secondary liver injury, but also activate the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway to enhance collagen I production and liver fibrosis. Binding of non-anticoagulant heparin (NAHP) to extracellular histones reduces histone toxicity, alleviates liver injury, and prevents histones from activating the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway. These results may explain why NAHP reduces liver fibrosis in this animal model, although further investigations are required.

INTRODUCTION

Liver fibrosis progression to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma is common, in China due to high incidence of hepatitis B and in western countries due to alcohol consumption and hepatitis C[1-3]. In 2017, liver cirrhosis caused more than 1.3 million deaths globally, and constituted 2.4% of total deaths[4]. However, elucidating the underlying molecular mechanism and the development of specific therapies for fibrosis and cirrhosis have progressed slowly and significant discoveries in this area are urgently needed.

Liver fibrosis is a natural wound healing response to chronic liver injury, which has many common causes, including viral infection, alcohol abuse, autoimmune diseases, drug toxicity, schistosomiasis, and metabolic diseases[5]. This process can be easily reconstituted in animals by administering chemicals toxic to hepatic cells, including CCl4, thioacetamide, and dimethyl or diethyl nitrosamine[6-8]. Bile duct ligation (BDL) and animal models mimicking specific chronic liver diseases are also used[6]. CCl4 is most commonly used to study the underlying molecular mechanisms and evaluate therapeutic reagents for inhibiting liver fibrosis in animals[6]. CCl4 directly damages hepatocytes by ligation of CCl3 to plasma, lysosomal and mitochondrial membranes, as well as to highly reactive free radical metabolites[9]. A single dose of CCl4 causes centrizonal necrosis and steatosis, with recurrent administration leading to liver fibrosis[10].

The pathological feature of liver fibrosis is the extensive deposition of extracellular collagen produced by myofibroblasts[1]. In the healthy liver, no myofibroblasts are present but they accumulate in the damaged liver and play a pivotal role in fibrogenesis[11]. Myofibroblasts are derived from different types of cells. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in the perisinusoidal Disse space are recognized as the most important source[12]. Bone marrow also contributes to both macrophages and to HSCs within the injured liver[13]. Recurrent injury, chronic inflammation and other chronic stimuli can cause HSCs to evolve into a myofibroblast-like phenotype and produce an extracellular matrix[14]. The myofibroblast-like phenotype also develops and expresses α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in vitro when quiescent HSCs were isolated and cultured over a period of 5-10 d[15].

HSCs activated both in vivo and in vitro express TLR4, CD14 and MD2, therefore, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is able to assemble a complex to activate TLR4 on HSCs[16]. TLR4 signals via MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways that can activate fibroblasts, to promote fibrogenesis in numerous organs, including the liver, lungs, kidneys, heart and skin[17-20]. Since circulating LPS is produced primarily in Gram-negative bacterial infections[21], ligands that activate TLR4 in chronic liver injury without concomitant bacterial infection are yet to be identified. Increased intestinal permeability allows LPS to enter the circulation in the later stages of liver cirrhosis, but this leakage has not been demonstrated in the early stages of fibrogenesis[22].

Liver cell injury and death also release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that may initiate the wound-repair process[23]. Extracellular histones, the most abundant DAMPs, have gained much attention in recent years, as they play key roles in many pathological processes and human diseases[24-35]. Histones are well-conserved proteins that are essential for DNA packaging and gene regulation[36]. During tissue damage and cell death, nuclear chromatin is cleaved into nucleosomes that are released extracellularly[37] and further degraded into individual histones[38]. Although histones are rapidly cleared by the liver[39] and rarely detected in blood[25,26,31,32], liver cell death is likely to release histones locally[40-43], which stimulate adjacent cells, including HSCs. Histones can activate TLR2, TLR4 and TLR9[24,40,43-46] in the early stage of chronic liver injury and fibrogenesis. Therefore, TLR4 activation is more likely to be maintained by extracellular histones rather than by LPS.

In this study, we investigated the roles and mechanisms of extracellular histones in liver fibrogenesis. Circulating histone levels were measured in a CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis model. Extracellular histones were used to stimulate human HSC cell lines to demonstrate their direct effect on collagen I production. In addition, we used non-anticoagulant heparin (NAHP) to neutralize circulating histones in both the cell culture system and mouse liver fibrosis model to explore the role of anti-histone therapy in reducing collagen I production and fibrosis. To clarify the potential molecular mechanisms, we used a TLR4-neutralizing antibody to block histone-enhanced collagen production by an HSC cell line and compared the fibrogenesis in TLR4 and MyD88 knockout mice with their wild-type (WT) parental mice in response to CCl4 treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

LX2 cells, a human HSC cell line, were purchased from Shanghai Meixuan Biological Sciences and Technology Ltd. and routinely cultured.

Histone treatment

After optimization of the doses and times, 0-20 μg/mL calf thymus histones (Merck, Armstadt, Germany) were added to cell culture medium to treat the LX2 cells. Medium with different concentrations of histones was changed every 48 h. On day 6, cell supernatant and lysates were collected for western blotting.

TLR4-neutralizing antibody and NAHP treatment

The neutralizing antibody, PAb-hTLR4, was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, United States). LX2 cells were treated with 5 μg/mL histones with and without 5 μg/mL antibody. NAHP was synthesized and characterized by Dr. Yates at the University of Liverpool. NAHP (25 and 50 μg/mL) was used to treat LX2 cells together with 5 μg/mL histones. The cell culture medium was changed every 48 h. The cell lysates of the treated LX2 cells were collected on day 6.

Western blotting

One milliliter of cell supernatant was collected and proteins were precipitated using ice-cold acetone and suspended in 50 μL clear lysis buffer [1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10% (v/v) glycerol, 120 mmol/L Tris–HCl, 25 mmol/L EDTA, pH 6.8]. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and lysed using clear lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using Bio-Rad protein assay kit II (Bio-Rad, Watford, United Kingdom). Both supernatant and cell lysates (20 μg protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Watford, United Kingdom). After blocking with 5% (w/v) dried milk in TBST buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20], the membranes were incubated with the sheep anti-human collagen I α1 antibody (1:2000, R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) overnight at 4 °C. After extensive washings with TBST, the membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-sheep IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 1:10000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, United States) for 1 h at room temperature. The protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Millipore). For β-actin, primary antibody was purchased from Abcam (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The band density was analyzed using Image J software and then the ratios of collagen I/β-actin were calculated.

Immunofluorescent staining

LX2 cells were seeded in eight-well chamber slides and treated with or without 5 μg/mL histones for 6 d. The cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with PBS + 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 10 min. After blocking with 5% (w/v) dried milk + 2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in PBS, the cells were incubated with sheep anti-human collagen I α1 antibody (1:200) or rabbit-anti-α-SMA antibody (1:200, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, United States) at 4 °C overnight. After extensive washing, the cells were incubated with anti-sheep-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, Abcam, 1:2000) or anti-rabbit-FITC (Abcam, 1:2000) at room temperature for 45 min. Following extensive washing, the slides were mounted on coverslips using mounting medium and antifade (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Renfrew, United Kingdom). The fluorescent images were visualized using an LSM-10 confocal microscope (excitation: 488 nm and emission: 512 nm).

Animals

Mice were housed and used in sterile conditions at the Research Centre of Genetically Modified Mice, Southeast University, Nanjing, China. The mice were kept in a temperature and humidity controlled laminar flow room with an artificial 10-14 h light/dark cycle. All mice had free access to water. Sample sizes were calculated using power calculation based on our previous data and experience. All procedures were performed according to State laws and monitored by local inspectors, and approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee at the Medical School of the Southeast University. Wang Z and Cheng ZX hold a full animal license for use of mice (Jiangsu Province, No. 2151981 and No. 2131272).

CCl4 model in ICR mice

Healthy male, 6-week-old ICR mice were purchased from Yangzhou University Animal Experiment Centre and divided randomly into three groups after blood sampling: (1) 5 μL/g body weight of 25% (w/v) CCl4 in olive oil injected intraperitoneally (i.p.), twice per week; (2) CCl4 + NAHP: On the day of CCl4 injection, 8 μL/g body weight NAHP (4 mg/mL in saline, filtered for sterility) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) every 8 h. On the remaining days, 8 μL/g body weight NAHP was injected s.c. every 12 h. Both groups of mice were monitored every day and euthanized by neck dislocation at 4, 8 and 24 h (3 mice per group at each time point) after the first dose of CCl4 each week to collect the blood and organs for further analysis (Supplementary Figure 1); and (3) Saline was injected i.p. and NAHP injected s.c. as a control; nine mice in total were euthanized by the end of 4 wk. No mice died before euthanization.

CCl4 model using genetically modified mice

C57BL/6JGpt (WT), TLR-4-KO (B6/JGpt-Tlr4em1Cd/Gpt) and MyD88-KO(B6/JGpt-Myd88em1Cd/Gpt) mice were purchased from Gempharmatech (Nanjing, China). Each type of mouse was divided into three groups as above after blood sampling. Eight mice in each group were treated with 5 μL/g body weight of 25% (w/v) CCl4 in olive oil i.p., twice per week for 4 wk. All mice were euthanized by neck dislocation and blood and organs were collected for further analysis (Supplementary Figure 2). No mice died before euthanization.

Tissue processing and staining

In our pathology laboratory, organ tissues were routinely processed and 4-μm sections were prepared. Staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Sirius red was routinely performed and α-SMA was detected by immunohistochemical staining using anti-α-SMA (Proteintech), as described previously[47]. Liver histological grading was as previously reported[48] and as performed by two investigators in a blinded manner. The staining areas of α-SMA and fibrosis were quantified using Image J software.

Measurement of blood histones and alanine aminotransferase

Venous blood was collected with citrate anticoagulant and immediately centrifuged at 1500 × g for 25 min at room temperature. Plasma was collected and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were measured by an automatic blood biochemical analyzer in the clinical laboratory and histone levels were measured by western blotting using anti-histone H3 (Abcam), as described previously[32]. Plasma and histone H3 protein (New England Biolabs, Herts, United Kingdom) as standard were subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrically transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). After blocking, the blot was probed by anti-histone H3 (Abcam, 1:2000) at 4 °C overnight. After extensive washings, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:10000) was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After extensive washing in TBST, ECL (Millipore) was used to visualize the protein bands, which were quantified against histone H3 protein standard to obtain the concentration of histone H3 in plasma using Image J software. The total histones were estimated based on the molar ratio of H3 in the cell nuclei.

Measurement of hydroxyproline in liver tissues

Part of the liver from mice was washed with saline and frozen at -80 °C. Two hundred and fifty milligrams of frozen liver tissues were ground using a low temperature Tissuelyser (Shanghai Jingxin Industrial Development Co. Ltd.) and hydroxyproline was measured using a colorimetric kit from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co. Ltd.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE). Differences in means between any two groups were compared using unpaired Student’s t test. Differences in means between more than two groups were compared using analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.

RESULTS

High levels of circulating histones are detected in mice treated with CCl4

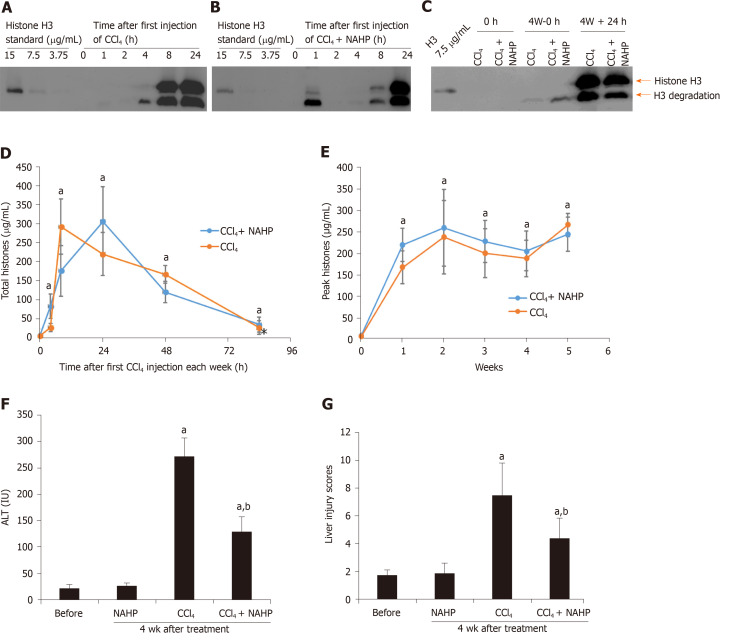

CCl4 is a hepatotoxin that directly damages hepatocytes. CCl4 administration in mice is the most commonly used animal model to generate liver fibrosis, but it is not clear whether high levels of histones actually exist under these conditions in the circulation. Circulating histone H3 was detected by western blotting and the total circulating histone levels were calculated based on these levels of H3, as described previously[32]. Histone H3 was detectable at 4 h after the first administration of CCl4 alone or CCl4 + NAHP (Figure 1A and B) at week 1. At week 4, before or 24 h after the last dose of CCl4, H3 was also detectable (Figure 1C). Total circulating histones reached peak values (around 200 μg/mL) between 8 and 24 h after CCl4 was administered and then gradually reduced to low levels (10-60 μg/mL) prior to the subsequent dose of CCl4 (Figure 1D). The mean ± SD of total histones during each week from 8 and 24 h after CCl4 injection is shown in Figure 1E. In contrast, histone H3 was barely detectable in the control group treated with saline + NAHP (data not shown). To monitor liver injury, blood ALT level was measured using a clinical biochemical analyzer. The mean ± SD from nine mice on day 28 was compared, and NAHP alone did not increase ALT levels, while CCl4 caused a significant elevation in circulating ALT (approximately 10-fold), but this elevation was significantly reduced by NAHP (approximately 40% reduction) (Figure 1F). Liver injury scores of H&E-stained liver sections were also significantly reduced by NAHP treatment (Figure 1G). These observations indicated that NAHP treatment reduced liver injury.

Figure 1.

Circulating histones are elevated in ICR mice treated with CCl4. Typical western blots of histone H3 standard and histone H3 in plasma from mice treated with the first dose of CCl4 (A) and CCl4 + non-anticoagulant heparin (NAHP) (B), and a typical H3 blot before and 24 h after the last dose of CCl4 (C); D: The mean ± SD of circulating histones at different time points, including 0 h (before the experiment), and 4, 8, 24, 48 and 84 h after first dose of CCl4 (orange) and CCl4 + NAHP (blue) of each week are presented. ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to time 0; E: The mean ± SD of peak circulating histones (8 and 24 h after first CCl4 injection of each week). ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to time 0 (before first injection). The mean ± SE of blood alanine aminotransferase levels (F) and liver injury scores (G) from nine mice in each group following 4 wk of treatment. ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to mice without treatment (before). bP < 0.05 compared to CCl4 group. ANOVA: Analysis of variance; NAHP: Non-anticoagulant heparin; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

Extracellular histones stimulate HSCs to increase production of collagen I and α-SMA

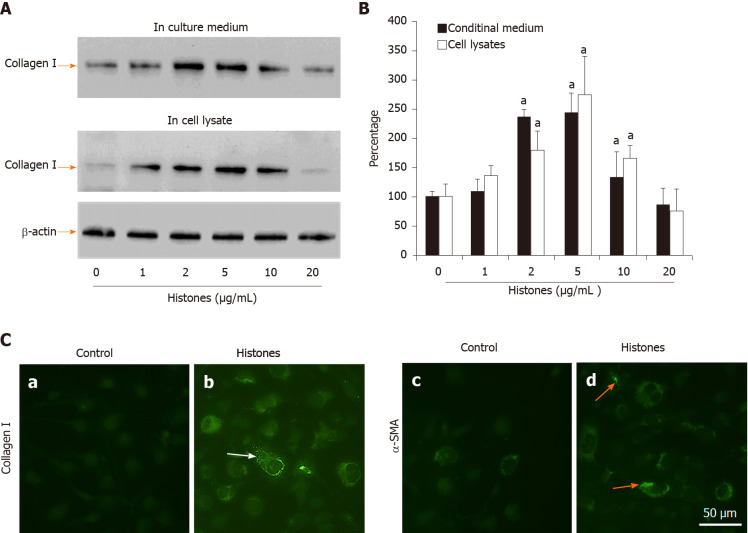

Extracellular histones are TLR ligands, including TLR2 and TLR4[40,45]; both of which signal via the downstream MyD88 pathway. During liver fibrogenesis, HSCs express TLR4 and its signaling enhances activation of fibroblasts[17]. We directly treated LX2 cells with calf thymus histones and found that histone concentrations between 2 and 10 μg/mL significantly increased collagen I production. Histones (5 μg/mL) incubated for 6 d were the optimal condition. This increased collagen I released into the culture media by nearly 2.5-fold and increased collagen I expression by 2.7-fold in cell lysates (Figure 2A and B). Concentrations of ≥ 20 μg/mL histones caused cell death (data not shown). Using immunofluorescent staining, we found that LX2 cells treated with 5 μg/mL histones were positively stained with anti-collagen I and anti-α-SMA compared to LX2 cells treated without histones (Figure 2C), supporting that LX2 cells were activated by histone treatment and induced collagen production.

Figure 2.

Extracellular histones induced collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin production in LX2 cells. A: Typical western blots of collagen I in medium (upper panel) and lysates (middle panel) of LX2 cells treated with different concentrations of histones at day 6. Lower panel: β-actin in the cell lysates; B: The mean ± SD of the relative percentages of collagen/β-actin ratios with untreated LX2 cells set at 100% from five independent experiments. Analysis of variance test, aP < 0.05 compared to untreated cells; C: Immunofluorescent staining of LX2 cells with anti-collagen I and anti-α- smooth muscle actin (SMA) antibodies. Control: Cells were treated with culture medium without histones for 6 d. Histones: Cells were treated with culture medium + 5 μg/mL histones. Typical images are shown. White arrows indicate staining for collagen I, yellow arrows indicate staining for α-SMA. Bar = 50 m. α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin.

NAHP reduces histone-enhanced collagen production in LX2 cells and liver fibrosis induced by CCl4

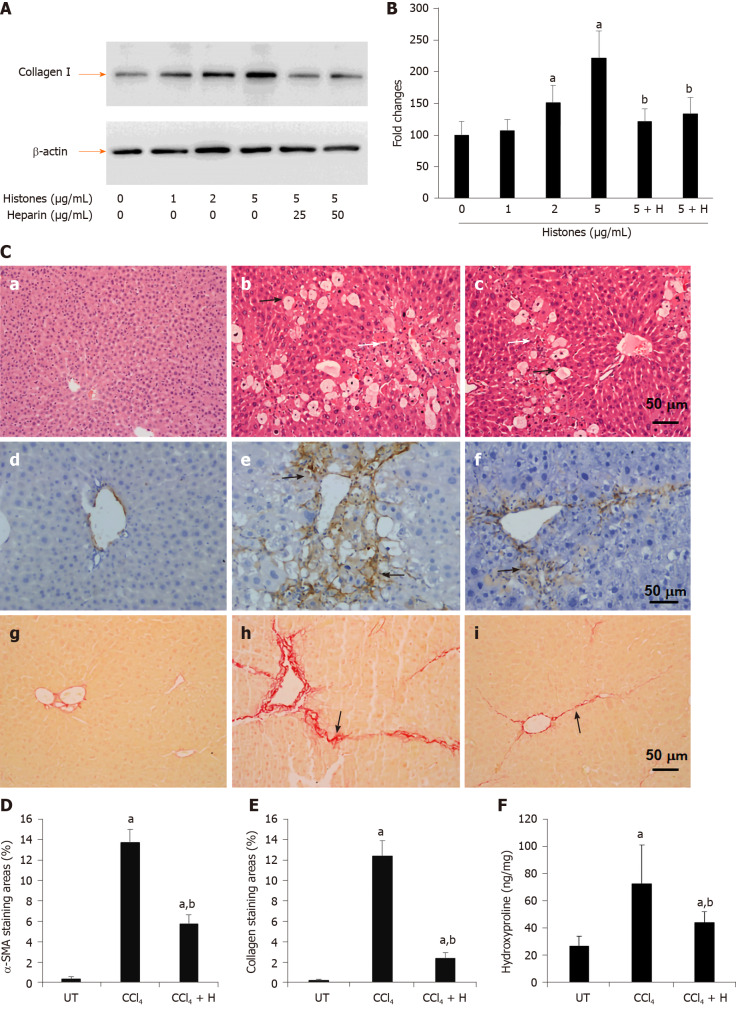

NAHP has been demonstrated to bind histones and block their cytotoxicity[26,32,49]. We added NAHP (25 and 50 μg/mL) to culture medium to neutralize 5 μg/mL calf thymus histones (Histones: NAHP approximately 1:2 and 1:4 molar ratio), and found that NAHP inhibited histone-enhanced collagen I synthesis in LX2 cells (Figure 3A and B). In H&E-stained liver sections from the CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis model, CCl4 caused extensive hepatocytic damage compared to controls (Figure 3C), including hepatocyte swelling, vacuole formation, necrosis, Kupffer cell proliferation and immune cell infiltration (Figure 3C). NAHP intervention significantly reduced CCl4-induced hepatocyte vacuolization, necrosis and immune cell infiltration (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical staining with anti-α-SMA showed a larger area of positive staining in CCl4-treated mice compared to controls (Figure 3C). In NAHP-treated mice, the CCl4-induced α-SMA staining was reduced (Figure 3C). Using Sirius red staining to visualize collagen, only the vascular walls were stained positively in controls (Figure 3C). In contrast, large areas of positive staining appeared in CCl4-treated mice (Figure 3C), which were reduced by NAHP intervention (Figure 3C). Using Image J software to quantify the areas of positive staining for α-SMA (Figure 3D) and collagen (Figure 3E), we demonstrated that NAHP significantly reduced both α-SMA and collagen production by 50%-70%. Using a colorimetric assay, hydroxyproline in liver tissues was detected and NAHP was shown to significantly reduce CCl4-induced hydroxyproline elevation by about 40% (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Effect of anti-histone reagent, non-anticoagulant heparin, on histone-enhanced collagen I production in LX2 cells and CCl4-induced fibrosis in mice. A: Typical western blots of collagen I in LX2 cells treated with histones or histones + non-anticoagulant heparin (NAHP). Beta-actin is shown as a loading reference; B: The mean ± SD of relative percentage of collagen/actin ratios in untreated LX-2 cells set at 100% from three independent experiments. ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to untreated cells. bP < 0.05 compared to cells treated with 5 μg/mL histones; C: Typical images of stained liver sections (hematoxylin and eosin staining: a-c; immunohistochemical staining with anti-α-SMA: d-f; and Sirius red staining: g-i) from normal mice (a, d, g); mice treated with CCl4 (b, e, h) and mice treated with CCl4 + NAHP (CCl4 + H) (c, f, i). Arrows in b and c: Black indicate hepatocyte swelling and white indicate necrosis and immune cell infiltration. Arrows in e and f: Indicate staining for smooth muscle actin. Arrows in h and i: Indicate collagen deposition. The mean ± SD of percentage of areas of staining for α-SMA (D) and Sirius red staining for collagen (E) (nine mice per group, and six randomly selected sections per mouse). ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to controls. bP < 0.05 compared to CCl4 alone; F: The mean ± SD of hydroxyproline levels in liver tissues from nine mice per group. ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to controls. bP < 0.05 compared to CCl4 alone. α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; ANOVA: Analysis of variance; NAHP: Non-anticoagulant heparin.

TLR4 is involved in histone-enhanced collagen production in LX2 cells and in liver fibrosis induced by CCl4

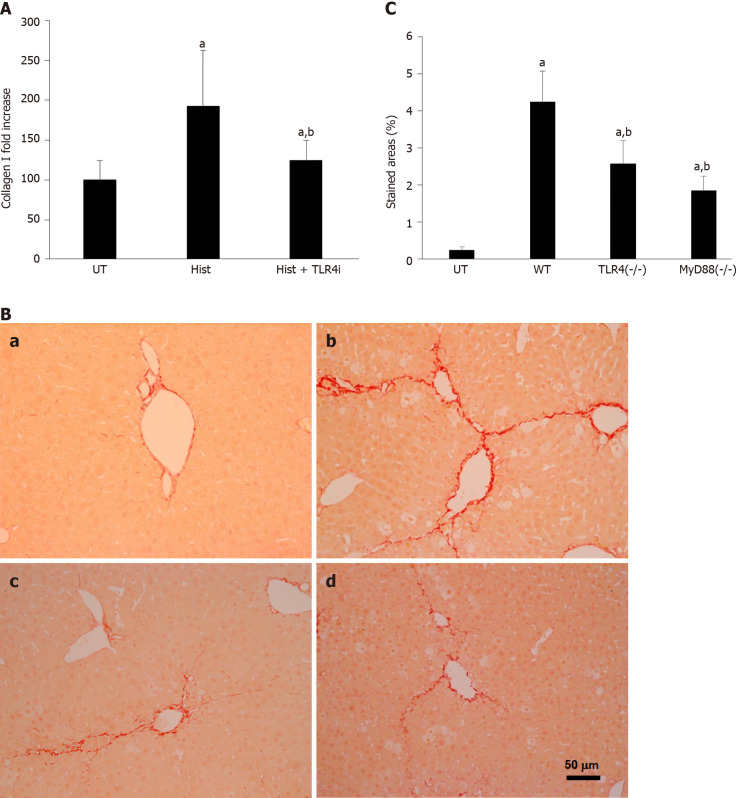

To understand how histones are involved in liver fibrosis, we specifically tested if histone-activated TLR/MyD88 signaling played a major role in this process. This hypothesis was based on previous reports that TLR4 and MyD88 were involved in fibrogenesis[17,19]. We used human TLR4-neutralizing antibodies to treat LX2 cells and found that histone-enhanced collagen I production was significantly reduced (Figure 4A). To confirm that the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway was involved in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, TLR4 and MyD88 gene knockout mice were used. The extent of fibrosis was significantly less in both TLR4-/- and MyD88-/- mice than in WT mice treated with CCl4 (Figure 4B and C). These results are consistent with a previous study that demonstrated TLR4 and MyD88 deficiency reduced liver fibrosis in a mouse BDL model[50]. These findings strongly suggest that extracellular histones activate the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway to enhance collagen I production and liver fibrosis. However, further investigation is required to substantiate this point and the downstream pathways.

Figure 4.

TLR4 is involved in histone-enhanced collagen I production and CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis. A: LX2 cells were treated with 5 μg/mL histones (Hist) in the presence or absence of TLR4 neutralizing antibody (TLR4i). The mean ± SD of the relative percentage of collagen Ι/β-actin ratios are presented with control (UT) set at 100% from three independent experiments. ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to UT. bP < 0.05 compared to histone alone; B: Typical images of Sirius red staining of liver section from untreated wt C57BL/j mice (a), CCl4-treated wt mice (b), and TLR4 and MyD88 knockout mice; C: The mean ± SD of stained areas of liver sections from untreated wt mice (UT), CCl4-treated wt mice (WT), CCl4-treated TLR4-/- and MyD88-/- mice. Eight mice were in each group and six sections from each mouse were analyses. ANOVA test, aP < 0.05 compared to untreated wt mice (UT). bP < 0.05 compared to CCl4-treated wt mice. ANOVA: Analysis of variance; wt: Wild type; UT: Control.

DISCUSSION

We proposed a novel concept that extracellular histones act as pathogenic factors in liver fibrosis. High levels of circulating histones in CCl4-treated mice were detected from 4 h after the first administration of CCl4 and remained high during fibrosis induction. In vitro, extracellular histones directly enhanced collagen I production in LX2 (HSC) cells by up to 2.7-fold. When NAHP was used to neutralize histones, it significantly reduced histone-enhanced collagen I production in LX2 cells and significantly reduced fibrosis in CCl4-treated mice. When TLR4 neutralizing antibody was used, histone-enhanced collagen I production in LX2 cells was also reduced. When CCl4 was injected into TLR4 or MyD88 knockout mice, they showed significantly less fibrosis compared to WT mice, suggesting that both TLR4 and MyD88 were involved in histone-enhanced fibrosis.

TLRs not only recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns from various microbial infections, but also respond to DAMPs from host cell damage[51]. TLR4 recognizes LPS from Gram-negative bacteria as well as histones released following cell death. TLR4 can activate nuclear factor-κB via MyD88[40,44,52,53]. The TLR4-MyD88 pathway has been demonstrated to promote liver fibrosis in a mouse BDL model by enhancing transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling[50]. LPS as a TLR4 ligand was elevated 3-6-fold in this model likely due to obstruction of bile ducts and subsequent bacterial infection[50]. However, circulating LPS concentration did not increase in the CCl4 mouse model[54]. Without infection, LPS from digestive tracts enters the circulation in the late stage of fibrosis or cirrhosis, while the wound-healing process is initiated immediately after injury. Therefore, LPS is unlikely to be an initiating factor in fibrosis. Extracellular histones are newly identified TLR4 ligands and are most likely to mediate the initial stage of fibrogenesis by activating the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway[40,44]. However, the downstream signaling pathways requires further experimental clarification. In addition, fibrogenesis not only involves collagen production but also many molecular and cellular mechanisms[55]. The co-operation of the TLR4-MyD88 pathway with other signaling pathways, such as TGF-β signaling and inflammatory response, also requires further investigation to determine their relative contributions to liver fibrosis.

The level of extracellular histones required for stimulating LX2 (HSC) cells is 2-10 μg/mL, which is lower than that detected in the circulation of CCl4-treated mice. All groups, including ICR mice treated with CCl4 and CCl4 + NAHP, and C57BL/6, TLR4-/- and MyD88-/- mice treated with CCl4, had comparable levels of peak circulating histones (Supplementary Figure 3). This is due to the severe and extensive damage to hepatocytes caused by the radical CCl3, a metabolite of CCl4. The highest levels of histones detected after CCl4 administration are comparable to those we have detected in critical illnesses[26,31,32] and are most likely able to cause further liver injury[56]. However, plasma can neutralize histones at a concentration of up to 50 μg/mL in vivo or ex vivo, making cells more resistant than those in culture medium[32]. Additionally, in our mouse model, the interval between two doses of CCl4 was 84 h; therefore, more than half of this period had histone levels around 50 μg/mL, which may be sufficient in maintaining TLR4 activation. Elevation of circulating histones was also found in many types of liver disease and the high levels of circulating histones could cause secondary liver injury[26,40,57]. Some human chronic liver diseases, such as chronic hepatitis B and C, and alcoholic and autoimmune liver diseases may have low but constant levels of circulating histones to serve as alarmins, which signal tissue injury and initiate repair processes. However, this needs further clinical investigation.

NAHP can bind to histones, but does not lower the levels of circulating histones. In the first week, NAHP seems to increase the levels of circulating histones in the CCl4-treated mice and this result could be explained by its ability to reduce histone clearance, as we have observed previously[26]. NAHP binding to extracellular histones prevents their binding to the cell plasma membrane and other targets, such as prothrombin[32-34] and thereby detoxifies histones. In this study, we found that ALT and liver injury scores were significantly reduced by NAHP in CCl4-treated mice, strongly indicating that high levels of circulating histones are toxic to liver cells, which can be neutralized by NAHP. This protective effect may also contribute to the reduction of liver fibrosis.

Heparin was reported to reduce collagen fiber formation and liver fibrosis two decades ago[58-60]. Enzymatically depolymerized low-molecular-weight heparins were shown to inhibit CCl4-induced liver fibrosis by reducing tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and interleukin (IL)-1β[61]. Although extracellular histones could enhance cytokine release, including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα[33,40], we suggest that the major mechanism for heparin-inhibited liver fibrosis is most likely due to its blocking the ability of extracellular histones to activate the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway. Heparin has been used as an anticoagulant for many decades and overdoses may cause bleeding, which can be avoided by using NAHP[26]. Additionally, NAHP alone appears to have no significant liver toxicity, but it significantly reduced histone-enhanced collagen I expression in LX2 cells and reduced CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Therefore, this novel finding may help to advance translating this old discovery into clinical application.

CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated that high levels of circulating histones exist in mice treated with CCl4 during induction of liver fibrosis. Treatment of LX2 cells with extracellular histones enhanced production of collagen I and α-SMA. Neutralizing histones using NAHP significantly reduced the production of collagen I and the extent of liver fibrosis. These data demonstrate that extracellular histones released after liver injury promote liver fibrosis. Blocking TLR4 receptor on LX2 cells reduced histone-enhanced collagen I production and CCl4 induced less fibrosis in TLR4 and MyD88 knockout mice than in WT parental mice, strongly suggesting that histone-enhanced collagen production is via the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway. However, there were a few limitations to this study. Firstly, in our in vivo study, no direct link was established between histones and their binding to TLR4. The relative contribution of the histone-TLR4-MyD88 axis and downstream signaling pathways is still not clear. Secondly, only one type of animal model for liver fibrosis was used and it may not truly represent the fibrosis caused by different diseases. However, the results are sufficient to demonstrate the novel concept that extracellular histones are involved in liver fibrosis. Thirdly, liver fibrosis is a complicated process involving many types of cells and signaling pathways. Besides collagen overproduction, many other biological processes are also involved in liver fibrosis. High levels of extracellular histones may also affect many other types of cells besides HSCs and collagen production. The detailed roles of extracellular histones in the complex processes of fibrogenesis require extensive investigation. Similarly, NAHP may have other effects besides blocking histones to activate TLR4 and to injury hepatocytes. Therefore, further in vivo mechanistic studies and development of better reagents to target histones and potential signaling pathways may offer a better understanding of fibrogenesis and more effective therapies in the future.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Currently, the molecular mechanisms of liver fibrosis are not fully understood. Recurrent liver injury or inflammation initiates wound healing along with fibrogenesis. However, what initiates this process is not clear. When cells die, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released. Histones are the most abundant DAMPs and are also ligands for TLR4, which in turn has been demonstrated to be involved in bile-duct-ligation-induced liver fibrosis. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is proposed to be a ligand for TLR4. Since recurrent liver injury does not naturally produce LPS but abundant extracellular histones, this study sought to investigate the potential roles of extracellular histones as TLR4 ligands in liver fibrosis.

Research motivation

Since our laboratory has been involved in studying the roles of DAMPs in critical illnesses, extracellular histones in liver fibrosis are of interest in terms of biological and clinical significance.

Research objectives

Our study aimed to clarify the roles of extracellular histones in fibrogenesis in vitro and in vivo.

Research methods

In our study, a hepatic stellate (HSC) cell line and animal models of liver fibrosis were used. Intervention studies with non-anticoagulant heparin (NAHP) to detoxify histones and TLR4-blocking antibodies to inhibit TLR4 were performed. In addition, TLR4 and MyD88 knockout mice were used to support the theory that the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway is involved in liver fibrosis in the CCl4 mouse model.

Research results

High levels of circulating histones were present when fibrosis was induced by CCl4 in the mouse model. Extracellular histones stimulated HSC cells in vitro to increase production of collagen I and alpha-smooth muscle actin. NAHP inhibited histone-enhanced collagen production in vitro, and reduce liver injury and fibrosis in vivo. TLR4 was involved in histone-enhanced collagen I production by HSC cells. In vivo, the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway mediated liver fibrosis, but whether circulating histones were the major activators of the pathway was not clear.

Research conclusions

Recurrent liver injury releases extracellular histones that potentially activate TLR4-MyD88 signaling to promote liver fibrosis. The ability of NAHP to detoxify circulating histones has the potential for treatment of liver injury and prevention of liver fibrosis.

Research perspectives

Future studies demonstrating the contribution of circulating histones to activation of the TLR4-MyD88 signaling and downstream pathways will validate their role in liver fibrosis. Development of effective anti-histone therapies to reduce liver injury and prevent liver fibrosis have potential in the management of diseases with recurrent liver injury.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all the staff in the animal house for their support and to the technicians in the pathology laboratory for technical support and clinical biochemistry for ALT measurement in Zhongda Hospital, Nanjing, China. Thanks to Professor Rudland P in the University of Liverpool for his critical reading and correction of the manuscript. Thanks to Dr. Lane S in The Department of Statistics, University of Liverpool for his assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by Medical School of Southeast University.

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: All procedures were performed according to State laws and monitored by local inspectors, and approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee at the Medical School of the Southeast University.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict interested has been claimed by any author.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: August 27, 2020

First decision: October 17, 2020

Article in press: December 6, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cuevas-Covarrubias SA, Cui J, Ilangumaran S, Tanabe S, Zhu Y S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Zhi Wang, Department of Pathology and Pathophysiology, Medical School, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China; Department of Gastroenterology, Zhongda Hospital, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China.

Zhen-Xing Cheng, Department of Pathology and Pathophysiology, Medical School, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China; Department of Clinical Infection, Microbiology and Immunology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom; Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230032, Anhui Province, China.

Simon T Abrams, Department of Clinical Infection, Microbiology and Immunology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom.

Zi-Qi Lin, Department of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Sichuan Provincial Pancreatitis Centre and West China-Liverpool Biomedical Research Centre, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

ED Yates, Department of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom.

Qian Yu, Department of Gastroenterology, Zhongda Hospital, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China.

Wei-Ping Yu, Department of Pathology and Pathophysiology, Medical School, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China.

Ping-Sheng Chen, Department of Pathology and Pathophysiology, Medical School, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China. chenps@seu.edu.cn.

Cheng-Hock Toh, Department of Clinical Infection, Microbiology and Immunology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom; Roald Dahl Haemostasis & Thrombosis Ctr, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom.

Guo-Zheng Wang, Department of Clinical Infection, Microbiology and Immunology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis -- from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2017 Cirrhosis Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:245–266. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Meyer C, Xu C, Weng H, Hellerbrand C, ten Dijke P, Dooley S. Animal models of chronic liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G449–G468. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00199.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liedtke C, Luedde T, Sauerbruch T, Scholten D, Streetz K, Tacke F, Tolba R, Trautwein C, Trebicka J, Weiskirchen R. Experimental liver fibrosis research: update on animal models, legal issues and translational aspects. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2013;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iredale JP. Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:539–548. doi: 10.1172/JCI30542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber LW, Boll M, Stampfl A. Hepatotoxicity and mechanism of action of haloalkanes: carbon tetrachloride as a toxicological model. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33:105–136. doi: 10.1080/713611034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii T, Fuchs BC, Yamada S, Lauwers GY, Kulu Y, Goodwin JM, Lanuti M, Tanabe KK. Mouse model of carbon tetrachloride induced liver fibrosis: Histopathological changes and expression of CD133 and epidermal growth factor. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisseleva T. The origin of fibrogenic myofibroblasts in fibrotic liver. Hepatology. 2017;65:1039–1043. doi: 10.1002/hep.28948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gäbele E, Brenner DA, Rippe RA. Liver fibrosis: signals leading to the amplification of the fibrogenic hepatic stellate cell. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d69–d77. doi: 10.2741/887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo FP, Alison MR, Bigger BW, Amofah E, Florou A, Amin F, Bou-Gharios G, Jeffery R, Iredale JP, Forbes SJ. The bone marrow functionally contributes to liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1807–1821. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maher JJ, McGuire RF. Extracellular matrix gene expression increases preferentially in rat lipocytes and sinusoidal endothelial cells during hepatic fibrosis in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1641–1648. doi: 10.1172/JCI114886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman SL, Rockey DC, McGuire RF, Maher JJ, Boyles JK, Yamasaki G. Isolated hepatic lipocytes and Kupffer cells from normal human liver: morphological and functional characteristics in primary culture. Hepatology. 1992;15:234–243. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–1055. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharyya S, Wang W, Qin W, Cheng K, Coulup S, Chavez S, Jiang S, Raparia K, De Almeida LMV, Stehlik C, Tamaki Z, Yin H, Varga J. TLR4-dependent fibroblast activation drives persistent organ fibrosis in skin and lung. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e98850. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huebener P, Schwabe RF. Regulation of wound healing and organ fibrosis by toll-like receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, Seki E. Toll-like receptors in liver fibrosis: cellular crosstalk and mechanisms. Front Physiol. 2012;3:138. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cengiz M, Ozenirler S, Elbeg S. Role of serum toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1190–1196. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zähringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F. Bacterial endotoxin: molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. FASEB J. 1994;8:217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pascual S, Such J, Esteban A, Zapater P, Casellas JA, Aparicio JR, Girona E, Gutiérrez A, Carnices F, Palazón JM, Sola-Vera J, Pérez-Mateo M. Intestinal permeability is increased in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1482–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vénéreau E, Ceriotti C, Bianchi ME. DAMPs from Cell Death to New Life. Front Immunol. 2015;6:422. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silk E, Zhao H, Weng H, Ma D. The role of extracellular histone in organ injury. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2812. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moxon CA, Alhamdi Y, Storm J, Toh JMH, McGuinness D, Ko JY, Murphy G, Lane S, Taylor TE, Seydel KB, Kampondeni S, Potchen M, O'Donnell JS, O'Regan N, Wang G, García-Cardeña G, Molyneux M, Craig AG, Abrams ST, Toh CH. Parasite histones are toxic to brain endothelium and link blood barrier breakdown and thrombosis in cerebral malaria. Blood Adv. 2020;4:2851–2864. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Z, Abrams ST, Alhamdi Y, Toh J, Yu W, Wang G, Toh CH. Circulating Histones Are Major Mediators of Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome in Acute Critical Illnesses. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e677–e684. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qaddoori Y, Abrams ST, Mould P, Alhamdi Y, Christmas SE, Wang G, Toh CH. Extracellular Histones Inhibit Complement Activation through Interacting with Complement Component 4. J Immunol. 2018;200:4125–4133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alhamdi Y, Toh CH. Recent advances in pathophysiology of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of circulating histones and neutrophil extracellular traps. F1000Res. 2017;6:2143. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12498.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T, Huang W, Szatmary P, Abrams ST, Alhamdi Y, Lin Z, Greenhalf W, Wang G, Sutton R, Toh CH. Accuracy of circulating histones in predicting persistent organ failure and mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1215–1225. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alhamdi Y, Toh CH. The role of extracellular histones in haematological disorders. Br J Haematol. 2016;173:805–811. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alhamdi Y, Abrams ST, Cheng Z, Jing S, Su D, Liu Z, Lane S, Welters I, Wang G, Toh CH. Circulating Histones Are Major Mediators of Cardiac Injury in Patients With Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2094–2103. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrams ST, Zhang N, Manson J, Liu T, Dart C, Baluwa F, Wang SS, Brohi K, Kipar A, Yu W, Wang G, Toh CH. Circulating histones are mediators of trauma-associated lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:160–169. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1037OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abrams ST, Zhang N, Dart C, Wang SS, Thachil J, Guan Y, Wang G, Toh CH. Human CRP defends against the toxicity of circulating histones. J Immunol. 2013;191:2495–2502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abrams ST, Su D, Sahraoui Y, Lin Z, Cheng Z, Nesbitt K, Alhamdi Y, Harrasser M, Du M, Foley J, Lillicrap D, Wang G, Toh CH. Assembly of alternative prothrombinase by extracellular histones initiate and disseminate intravascular coagulation. Blood. :2020. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alhamdi Y, Zi M, Abrams ST, Liu T, Su D, Welters I, Dutt T, Cartwright EJ, Wang G, Toh CH. Circulating Histone Concentrations Differentially Affect the Predominance of Left or Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Critical Illness. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e278–e288. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holdenrieder S, Stieber P, Bodenmüller H, Fertig G, Fürst H, Schmeller N, Untch M, Seidel D. Nucleosomes in serum as a marker for cell death. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2001;39:596–605. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2001.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D, Ingram A, Lahti JH, Mazza B, Grenet J, Kapoor A, Liu L, Kidd VJ, Tang D. Apoptotic release of histones from nucleosomes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12001–12008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gauthier VJ, Tyler LN, Mannik M. Blood clearance kinetics and liver uptake of mononucleosomes in mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:1151–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J, Zhang X, Monestier M, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones are mediators of death through TLR2 and TLR4 in mouse fatal liver injury. J Immunol. 2011;187:2626–2631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Gou C, Yao L, Lei Z, Gu T, Ren F, Wen T. Patients with HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure have increased concentrations of extracellular histones aggravating cellular damage and systemic inflammation. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:59–67. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang R, Zou X, Tenhunen J, Tønnessen TI. HMGB1 and Extracellular Histones Significantly Contribute to Systemic Inflammation and Multiple Organ Failure in Acute Liver Failure. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:5928078. doi: 10.1155/2017/5928078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang H, Evankovich J, Yan W, Nace G, Zhang L, Ross M, Liao X, Billiar T, Xu J, Esmon CT, Tsung A. Endogenous histones function as alarmins in sterile inflammatory liver injury through Toll-like receptor 9 in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54:999–1008. doi: 10.1002/hep.24501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allam R, Scherbaum CR, Darisipudi MN, Mulay SR, Hägele H, Lichtnekert J, Hagemann JH, Rupanagudi KV, Ryu M, Schwarzenberger C, Hohenstein B, Hugo C, Uhl B, Reichel CA, Krombach F, Monestier M, Liapis H, Moreth K, Schaefer L, Anders HJ. Histones from dying renal cells aggravate kidney injury via TLR2 and TLR4. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1375–1388. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118:1952–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo HY, Cui ZJ. Extracellular Histones Activate Plasma Membrane Toll-Like Receptor 9 to Trigger Calcium Oscillations in Rat Pancreatic Acinar Tumor Cell AR4-2J. Cells. 2018;8:3. doi: 10.3390/cells8010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Li W, Limbu MH, Li Y, Wang Z, Cheng Z, Zhang X, Chen P. Effects of Simultaneous Downregulation of PHD1 and Keap1 on Prevention and Reversal of Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:555. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abrams ST, Morton B, Alhamdi Y, Alsabani M, Lane S, Welters ID, Wang G, Toh CH. A Novel Assay for Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation Independently Predicts Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Mortality in Critically Ill Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:869–880. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201811-2111OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang X, Li L, Liu J, Lv B, Chen F. Extracellular histones induce tissue factor expression in vascular endothelial cells via TLR and activation of NF-κB and AP-1. Thromb Res. 2016;137:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang K, Yang X, Wu Z, Wang H, Li Q, Mei H, You R, Zhang Y. Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharide Protected CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis Through Intestinal Homeostasis and the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:240. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S, Wang J, Shanmukhappa SK, Gandhi CR. Toll-Like Receptor 4-Independent Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Fibrosis and Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Liver Injury in Mice: Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:1356–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kisseleva T, Brenner D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. :2020. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wen Z, Lei Z, Yao L, Jiang P, Gu T, Ren F, Liu Y, Gou C, Li X, Wen T. Circulating histones are major mediators of systemic inflammation and cellular injury in patients with acute liver failure. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2391. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen Z, Liu Y, Li F, Ren F, Chen D, Li X, Wen T. Circulating histones exacerbate inflammation in mice with acute liver failure. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:2384–2391. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Akimoto K, Ikeda M, Sorimachi K. Inhibitory effect of heparin on collagen fiber formation in hepatic cells in culture. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:533–538. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi J, Hao JH, Ren WH, Zhu JR. Effects of heparin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1611–1614. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sorimachi K. Inhibition of collagen fiber formation by dextran sulfate in hepatic cells. Biomed Res. 1992;13:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan Y, Guan C, Du S, Zhu W, Ji Y, Su N, Mei X, He D, Lu Y, Zhang C, Xing XH. Effects of Enzymatically Depolymerized Low Molecular Weight Heparins on CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:514. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.