Abstract

Introduction

Patient satisfaction is a key factor in the evaluation of the quality of healthcare services. Measuring patient satisfaction is common in outpatient, specialist, and hospital healthcare, and is also significant in relation to pharmaceutical services. The pharmacy market in Poland has been undergoing transformations for many years. Legal regulations implemented in 2002 resulted in a rapid growth of pharmacy chains and a decrease in the number of independent pharmacies. This situation may have translated into changes in the quality of pharmaceutical services.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate patient satisfaction with services provided in independent pharmacies and pharmacy chains in Poland.

Patients and Methods

A total of 163 patients using randomly selected community pharmacies in Poland were enrolled in the study. A modified Community Pharmacy Patient Questionnaire (CPPQ) was used.

Results

The patients highly valued pharmaceutical services provided in Polish pharmacies. The level of service was slightly higher in pharmacy chains. The lowest-rated area was the provision of information on medications, with independent pharmacies higher-rated in this respect. The patients were open to additional services in pharmacies and supported the development of pharmaceutical care.

Conclusion

Independent pharmacies and pharmacy chains ensure a similar level of services for patients in Poland. Pharmacy staff should place a special emphasis on providing patients with comprehensive information on medications. The development of pharmaceutical care in Poland will require appropriate legislative preparation.

Keywords: pharmaceutical service, pharmacy, patient satisfaction, pharmaceutical care

Introduction

Patient satisfaction is currently considered one of the main indicators of the quality of medical services, which is of particular importance in patient-centered care.1–3 Patient satisfaction is defined as a subjective emotional opinion based mainly on patient expectation and their previous experiences compared to the currently received service. In the services sector, special attention is paid to the fact that patient satisfaction is connected not only with what the patient receives but also largely with how the entire process proceeds.4–7 For this reason, getting to know patient needs and expectations, such as their satisfaction with the services provided, seems essential for the development of patient-centered care.

Despite numerous studies on patient satisfaction with medical services provided in both basic and specialist healthcare as well as in hospitals,8–11 there are relatively few results in literature regarding patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical services provided in community pharmacies.

Not only do pharmaceutical services include trading in medications and medicinal products and preparing compounded medications but also in providing information on medications and medicinal products.12 In addition, pharmacies provide pharmaceutical care within which pharmacists cooperate with patients and representatives of medical professionals to prevent, identify, and solve medication-related problems. Patient access to pharmaceutical care ensures medication safety, maximized treatment effect, and increased quality of life,13,14 which is why pharmacists and pharmaceutical services are an integral element impacting patient health.

Since 2002, the number of pharmacies in Poland has increased rapidly due to deregulation of the pharmaceutical market. Under the implemented regulations, any natural or legal person or company is allowed to operate a pharmacy, even up to 10% of the pharmacies in Poland, which has resulted in a rapid growth in these entities and a dynamic development of pharmacy chains, leading to the collapse of many independent pharmacies. In 2017, an amendment to the Pharmaceutical Law Act (“Pharmacy for the Pharmacist”) was passed. That new legislation stipulated that a permit to run a pharmacy would be granted only to authorized pharmacists, reducing the number of pharmacies and introducing geographic and demographic limits. Currently, there are about 13 thousand community pharmacies in Poland. The market is divided into independent pharmacies (constituting about 57% of the market) and pharmacy chains (43% of the market).15 The rapid growth in pharmacies in Poland has led to changes in the activities of many entities, especially those that have focused largely on efficient sales, minimizing the role of patient health support. Due to the ban on pharmacies advertising their services, in order to maximize profits pharmacies have launched promotions and loyalty programs, and have focused on selling the highest margin products (OTC medications and dietary supplements).

Considering these changes in the community pharmacy market, evaluating patient satisfaction can play a significant role in the further development of these facilities. Not only are pharmacies healthcare facilities but also business entities, thus they are subject to market mechanisms. Marketing management of a pharmacy is based on measuring and striving to meet customer satisfaction. Those pharmacies that do not try to adjust to patient needs will not be able to maintain their position in the competitive pharmaceutical market. Knowledge of the level of service provided and customer opinions of the pharmacy staff, its range of products, services, and ambience are extremely important factors in enhancing the development of pharmaceutical services in Poland.

Objectives

The main objective of this study was to determine the level of patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical services provided in community pharmacies in Poland. For the purposes of this study, it was important to compare patient satisfaction with the services provided in independent pharmacies and pharmacy chains, as well as to get to uncover the factors that influenced the patients’ choice of pharmacy and expectations of pharmaceutical services. This study is also intended to show the lowest-rated aspects in the current services of pharmacies in Poland.

Patients and Methods

The study was conducted among patients using pharmaceutical services. An anonymous questionnaire was used,16 based on the Community Pharmacy Patient Questionnaire (CPPQ) used in Great Britain for the obligatory annual patient evaluation of the quality of pharmaceutical services. The questionnaire was developed by the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) with the objective of providing community pharmacies with feedback regarding their services. The study was conducted in randomly selected four community pharmacies in Poland (2 chain pharmacies and 2 independent pharmacies, located in different voivodships). The pharmacies had specially marked ballot boxes where patients placed their completed questionnaires. The study was carried out between March and June 2017. Participation in the study was voluntary, and prior to enrolment the patients were informed about its anonymous character. Each study participant gave oral consent to the study. All information regarding the study, including the purpose of the study, was presented in the letter to the participant attached to the questionnaire. Questionnaires were completed by 172 people, of which 9 were excluded due to improper or incomplete answering. The analysis included 163 questionnaires. Of the 163 respondents, 85 used services provided by pharmacy chains, and 78 by independent pharmacies.

The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions divided into 4 basic parts. The first part concerned general characteristics of the respondents (sex, age, place of living, chronic diseases history of hospitalization). The second part aimed at determining the profile of pharmaceutical service use (frequency and reason for using the services), and eliciting patient expectations of pharmacies (factors influencing the choice of pharmacy, provision of additional services). The third part was designed to evaluate the pharmacy staff, product range, and the premises. The fourth part was intended to provide a direct evaluation of patient satisfaction with a visit to a pharmacy. The results of the third and fourth parts of the questionnaire were compared between independent pharmacies and pharmacy chains.

A large proportion of the questionnaire contained statements where respondents were asked to choose one out of five options (Likert scale): 5 - yes, 4 - rather yes, 3 - I do not know, 2 - rather no, 1 - no. A numeric value was assigned to each statement to calculate the median of responses. For some calculations, the sum of ‘yes’ and “rather yes” responses were considered positive, while the sum of “no” and “rather no” responses were considered negative.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Group

Of the 163 respondents, 117 (71.2%) were women and 46 (28.2%) men. Most respondents were 20–29 years of age (n=83), then 30–39 years of age (n=24), 50–59 years of age (n=22), 40–49 years of age (n=16), over 60 years of age (n=14), and up to 19 years of age (n=4) (all respondents were over 18 years of age).

Most respondents lived in cities of between 100,000 and 500,000 inhabitants (n=52), in villages (n=35), in cities of between 20,000 and 100,000 inhabitants (n=31), in towns of up to 20,000 inhabitants (n=24), and in cities above 500,000 inhabitants (n=21).

The vast majority of respondents declared no chronic diseases (n=105). One or more chronic diseases were reported by the remaining respondents. Twenty-eight respondents indicated chronic diseases not included in the questionnaire, eg, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s disease, GERD, and glaucoma. As for cardiovascular diseases, the biggest group of respondents suffered from hypertension (n=21), then diabetes (n=12), coronary heart disease (n=4), another cardiovascular disease (n=3), and heart failure (n=1).

The questionnaire also contained a question about hospitalization due to a heart attack or pain in the chest over the last 12 months. Most respondents (n=154) had not been hospitalized in that period, 7 confirmed hospitalization in that period, and 2 people did not remember.

The Profile of Pharmaceutical Service Use and Patient Expectations

Over half of the respondents visited pharmacies less than twice a month (52%), and 5% of the respondents visited pharmacies 1–2 times a week. The most common reasons why the patients visited pharmacies were filling prescriptions (n=100), buying cold or flu medications (n=61), or buying painkillers (n=42).

The respondents were also asked whether the factors included in the questionnaire had influenced their choice of a pharmacy compared to others. The most common responses were: convenient location of the pharmacy (median 4.63), low prices of medications (median 4.56), and a broad access to medications (median 4.50). Professional service was of great significance (median 4.39). The possibility to discuss health problems and doubts regarding health and use of medications was reported as least important.

Most respondents think that basic examinations such as measuring blood pressure (n=139) and blood glucose (n=124) should be carried out in pharmacies. Although the respondents less frequently reported measuring body weight (n=105), and cholesterol level (n=97), over half of them are of the opinion that this service should be available in pharmacies. Some of the respondents declared that they would take the opportunity to consult a pharmacist on health issues. The possibility of consulting a pharmacist about healthy eating and recovery from addiction would be the most welcome by the patients, while the possibility of discussing matters relating to personal hygiene would be the least popular.

Evaluation of the Pharmacy Staff, Product Range and Premises

The vast majority of the respondents had a positive opinion of the pharmacy staff (the questions concerned all pharmacy employees). They mostly reported that the staff were kind and respected patients (median 4.60), used plain language (median 4.59), did not invade their personal space (4.49), and were willing to help (median 4.45). The lowest number of positive responses was noted in questions about being remembered by the pharmacy staff (3.04) and the interest of the pharmacy staff in patient health (3.21).

With regard to the pharmacy product range and premises, in the whole group of patients, the highest-rated statements included: the pharmacy is clean and well-maintained (median 4.84), and the pharmacy usually sells medications that I need (median 4.56). The lowest-rated statement was the number of staff (median 4.13).

As far as ambience and product range are concerned, chain pharmacies are slightly higher rated than independent pharmacies. The only aspect rated slightly higher in independent pharmacies was the wide range of products (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of patient evaluation medians of pharmacy chains and independent pharmacies in relation to ambience and product range.

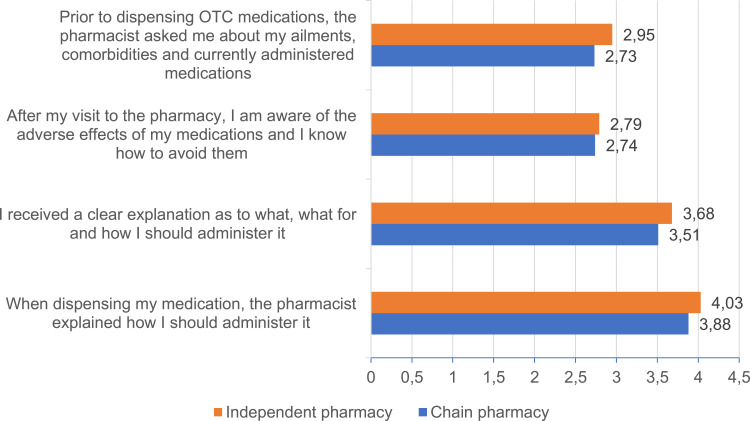

Pharmacies obtained bad results in relation to providing information on medications. The respondents mostly indicated a lack of information on the adverse effects of medications and a lack of questions about ailments, comorbidities, and currently administered medications. Independent pharmacies obtained better results in every aspect of this area than pharmacy chains (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of patient evaluation medians of pharmacy chains and independent pharmacies in relation to providing information on medications.

Level of Patient Satisfaction with a Visit to a Pharmacy

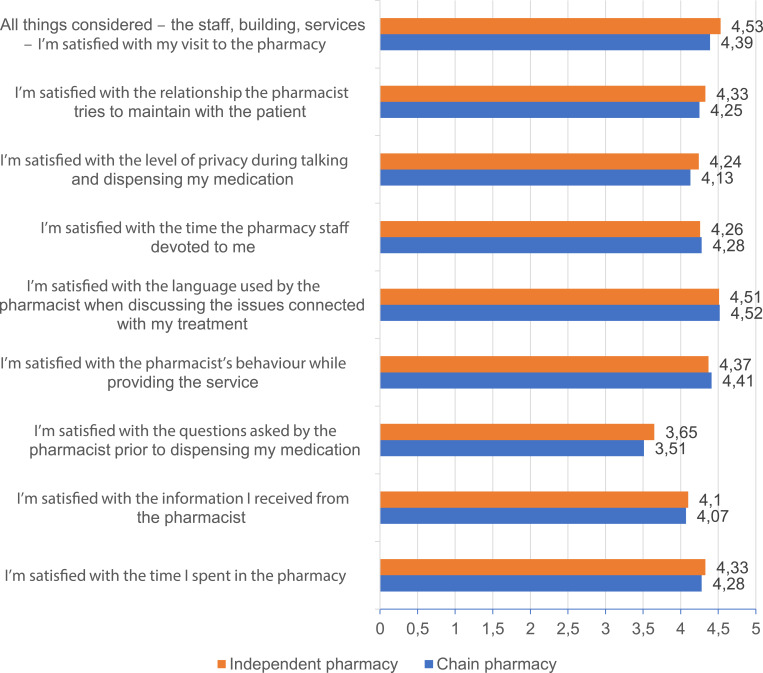

In total, 93.9% of the respondents were satisfied with their visit to the pharmacy. The respondents were most satisfied with the behavior and communication of the staff. An equally high level of satisfaction was observed in the case of the time devoted to patients and the total time spent in the pharmacy. The greatest level of dissatisfaction was noted in relation to providing information on medications and history taking.

As far as the evaluation of the entire visit to the pharmacy is concerned, independent pharmacies were rated slightly higher. They gained higher scores in the areas of ensuring privacy, relationship between the pharmacist and the patients, information provided to the patient, or interview with the patient before drug dispensing. Pharmacy chains prevail with regard to the language used by the staff, general behavior of the staff, and the time devoted to a given patient (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of patient evaluation medians of a visit to the pharmacy depending on the kind of the pharmacy.

Discussion

The outcomes of this study indicate that the quality level of pharmaceutical services provided in Poland is high. The patients gave the lowest ratings to history taking by the dispensing staff prior to dispensing a given product. They also indicated insufficient information on medications from pharmacists, namely in pharmacy chains. Similar results were obtained 10 years earlier by Merks et al17 and researchers in other countries.18,19 This situation, indicating a lack of change in this area, is alarming. Different outcomes were achieved in Slovakia and Slovenia, where the level of providing information on medications was rated by patients as high.20,21

One of the role models of high-quality pharmaceutical care in Europe is Great Britain, where all pharmacies are obliged to carry out an annual questionnaire (CPPQ), which served as a basis for the creation of the Polish questionnaire applied in this study. The requirement of measuring patient satisfaction imposed by an independent body (which is the case in Great Britain) undoubtedly influences the pharmacy determination to provide high-quality services. In addition, pharmacies in Great Britain are obliged to publish their outcomes (in pharmacies as leaflets or posters, or on the pharmacy or NHS website). Each report is supposed to indicate the areas with the best results and areas that need improvement, including the description of undertaken or planned actions. Results obtained by pharmacies translate into the level of financing of pharmaceutical services from public funds (NHS).16

In this study, ambience of the premises and available products were rated relatively high in the entire group of respondents. According to the patients, the pharmacies were clean, well-maintained and well-organized. The biggest number of negative responses was noted in relation to the number of staff – every tenth respondent reported that the number of staff was insufficient and the time of waiting for the service was too long.

The patients in Poland did not indicate problems with access to medications. The vast majority of the patients reported that the pharmacies offered a wide range of products, including OTC medications, dietary supplements, and cosmetics, and that the medications they needed were delivered quite quickly. Despite the fact that pharmacy chains obtained better results in this study, both pharmacy chains and independent pharmacies were rated highly by the patients.

When choosing a pharmacy, the patients were usually guided by the broadly defined good image of the pharmacy. The most important factors included the pharmacy location, availability, and prices of medications, as well as the qualifications and behavior of the staff. Some patients also indicated advice given by pharmacists as the factor influencing their choice of pharmacy,17,21–23 which is of great significance in relation to commonly practiced self-treatment. With regard to the location, the patients chose those pharmacies that were in close proximity to a hospital, doctor’s surgery, or their residence. Other important factors most frequently reported by the respondents were similar to those in studies carried out by other Polish and foreign authors.17,22

For some patients, the price was an important evaluation criterium. Low prices in pharmacies increase patient satisfaction. Every effort should therefore be made so that patients stay loyal to the pharmacy even after a change in prices. Implementing additional services and increasing their quality are non-material values and can translate into enhanced patient satisfaction.

The appropriate decor and product displays played an important role for the patients. The layout should be clear and adjusted to current patient needs, eg, depending on the season of the year. Additional elements such as kids’ corners and water dispensers will help build a positive image of the pharmacy. Due to a too narrow product range, patients can turn to other pharmacies, while a wide selection of products, positively rated in this study, will encourage them to use the services of this particular pharmacy.17,22,23

A factor that can have a significant impact on pharmacy competitiveness is the implementation of pharmaceutical care or its elements. By assumption, it results in more effective pharmacotherapy and thus decreased total costs of treatment, which can translate into an increased number of regular patients. Most common problems of contemporary pharmacotherapy are non-adherence and polypragmacy. Non-adherence is one of the most common reasons for ineffective pharmacotherapy. Patients often do not adhere to doctors’ instructions in relation to the administration of medications, and therefore it is important that pharmacists reinforce the dosing regimen and purpose of a given medication when talking to patients.

What is more, in respect to self-treatment, taking a short history of a patient’s health condition and currently administered medications will allow the staff to choose the most appropriate products. Providing information on medications and adjusting them to a given patient was one of the lowest-rated elements of pharmaceutical services in the Polish pharmacies. Nevertheless, studies show that this kind of information significantly increases adherence, improves treatment outcomes, and accelerates the achievement of target treatment effects.24–26

Polish pharmacists should pay more attention to patients and their ailments, as well as to informing them of the effects of a given medication. This information is extremely important for the safety of pharmacotherapy and can contribute to an increased adherence.27 Labelling medications prior to dispensing can also be helpful. As high as 70.5% of the respondents would like information on the dosing regimen to be dispensed as an additional printout. This percentage has significantly increased compared to 2011, when according to studies by Merks et al it was 46%.17

Pharmaceutical care improves the relationships between patients and pharmacists. In many countries, eg, Great Britain and the USA, pharmaceutical care has become an indispensable, if not one of the basic elements of pharmaceutical services.28–30

Patients in Poland consider pharmacists as experts in medicinal products. Most respondents of this study are of the opinion that pharmacists are an integral part of healthcare. This opinion has changed significantly in the course of the last year. In studies by Świeczkowski et al31 just 14% of the respondents thought that pharmacists practiced a profession connected with healthcare. Changing the patients’ opinions in this respect can largely facilitate the implementation of reliable pharmaceutical care. With lesser ailments, patients turn more and more often to pharmacies.5,31,32 Although the most frequently indicated reason for visiting pharmacies was still filling prescriptions, an increasing number of respondents also report buying OTC medications and other products, as well as getting professional advice. The expertise of the staff and the quality of advice are of great importance for patients in Poland. This tendency is also observed in other countries.5,21,23

The staff of the pharmacies participating in this study were considered pleasant and competent. Yet, the patients often think that they are not remembered and do not feel the staff are interested in their health condition. These outcomes are confirmed by existing studies.17,20 The staff are able to remember regular patients, and most of the respondents visit pharmacies less than twice a month. Implementing the network of a special computer system that would enable pharmacists to enter and store patient data could be a good solution that would facilitate pharmaceutical care in Poland.

The patients are also very enthusiastic about the implementation of additional services to pharmacies, and the positive effects of such activities have been emphasized by many authors.5,17,31 Making examinations in pharmacies can contribute to early diagnosis of some diseases, eg, hypertension and diabetes. The patients are also willing to take part in training sessions on the operation of medical equipment. Being able to use eg, insulin pens and glucometers, can be very helpful in regulating blood glucose level among diabetics. Patients would like to have the possibility to consult on not only medication but also health-related issues with pharmacists. Although most respondents think that their private space is not invaded during a visit to the pharmacy, studies by Świeczkowski et al31 show that to carry out such consultations with patients, it is worth designating a special area in a pharmacy to ensure a higher level of privacy.

This study indicates that the level of patient satisfaction with pharmacy services is relatively high. The services provided by pharmacy chains are rated slightly higher than those in independent pharmacies. Providing patients with information on medications in pharmacy chains is however lower-rated. Patients in Poland trust pharmacists and are open to other services provided in pharmacies, and thus expect the development of pharmaceutical care in Poland. Patients are also open to educational services that could be offered by pharmacies, but this would require some legal changes that would enable the implementation of comprehensive pharmaceutical care to pharmacies in Poland.

The role of community pharmacies and pharmacists in the British healthcare system is much greater than in Poland. Community pharmacies (contrary to hospital pharmacies) are considered primary care and therefore the legal regulations developed in this area are to raise the standards of functioning of this part of the market, stimulating the competitiveness of pharmacies, innovativeness of services, and promotion of pharmaceutical care.

British pharmacies are currently financed by relevant primary care trusts (PCT) that are part of the National Health Service. Local PCTs have their own budgets and establish commissions for health services offered at various levels of the healthcare system (hospital care, outpatient care), as well as remuneration for medical staff and reimbursement of prescriptions. Independent PCT branches perform a supervisory function over pharmacies with regard to correctness and quality of pharmaceutical services. Polish pharmacies are not financed from public funds, and their profits depend on the margin imposed on products (which in many cases is determined by law). Pharmaceutical care services are not reimbursed in Poland. These issues are necessary to regulate. Providing clear financing conditions for pharmaceutical services can significantly affect their quality.

As numerous studies have shown, comprehensive pharmaceutical care will increase patient medication safety, raise their awareness of administered medications, and enhance treatment effectiveness, resulting in more effective disease management.13,14,27,28,33,34 Pharmaceutical care improves the process of providing services for patients, increases access to services, and reduces the global cost of treatment.

However, the implementation of comprehensive pharmaceutical care requires standardization of the processes conducted in pharmacies, including standardization of patient service, ensuring care of pharmaceutical services, which is the case in Great Britain. Implementing the requirement of an annual evaluation of pharmaceutical services by patients imposed by legal regulation, supervised by an independent body, and associated with the level of financing of pharmacies would undoubtedly increase the quality of provided services.

Limitations

We are aware that our research, despite our efforts, has limitations. First of all, the study was conducted only in four pharmacies in Poland. Although they were located in other cities, the final results may not fully reflect the results of Polish patients. Additionally, the study covers a relatively small group of patients; most of them were under 40 years of age and had no chronic diseases, which may not be a representative sample of all pharmacy patients. This attempt will influence the final results, including the need for specific services. Nevertheless, it was the first study of this type in Poland, being a kind of pilot. Further research is needed in this area involving a more extensive and more diverse patient population.

Conclusions

The level of patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical services in Poland can be considered high, regardless of the kind of pharmacy (independent or chain), although pharmacy chains were slightly higher-rated by the patients. One of the lowest-rated area of pharmaceutical service in all the pharmacies was providing information on dispensed medications by the pharmacy staff. The patients are largely interested in additional services provided by pharmacies, including basic examinations and training sessions (also in the field of health education) for particular groups of patients.

Ensuring high-quality pharmaceutical services requires a regular evaluation of patient satisfaction. The quality of services should be monitored by independent institutions, as exemplified in Great Britain. Combining the quality of pharmaceutical services with the amount of funds can have an additional impact on the provision of pharmaceutical services, and their regular evaluation by patients is an essential condition for the efficient functioning of pharmaceutical care.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by Ethics Committee at the Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Poland (KB 165/2017). We confirm that consent was received from the study participants and that the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. The Ethics Committee approved verbal consent to conduct the study received from study participants.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Fix GM, VanDeusen Lukas C, Bolton RE, et al. Patient-centred care is a way of doing things: how healthcare employees conceptualize patient-centred care. Health Expect. 2018;21(1):300–307. doi: 10.1111/hex.12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaney LJ. Patient-centred care as an approach to improving health care in Australia. Collegian. 2018;25(1):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2017.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluyas H. Patient-centred care: improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs Stand. 2015;30(4):50–57. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.4.50.e10186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Cardenas V, Benrimoj SI, Ocampo CC, et al. Evaluation of the implementation process and outcomes of a professional pharmacy service in a community pharmacy setting. A case report. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(3):614–627. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jose J, Al Shukili MN, Jimmy B. Public’s perception and satisfaction on the roles and services provided by pharmacists – cross sectional survey in Sultanate of Oman. Saudi Pharm J. 2015;23(6):635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Amenta P. Conceptualisation of patient satisfaction: a systematic narrative literature review. Perspect Public Health. 2015;135(5):243–250. doi: 10.1177/1757913915594196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xesfingi S, Vozikis A. Patient satisfaction with the healthcare system: assessing the impact of socio-economic and healthcare provision factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1327-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):2–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Ball J, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospital care and nurses in England: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e019189. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zgierska A, Rabago D, Miller MM. Impact of patient satisfaction ratings on physicians and clinical care. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:437–446. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S59077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lake ET, Germack HD, Viscardi MK. Missed nursing care is linked to patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional study of US hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(7):535–543. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allemann SS, van Mil JW, Botermann L, et al. Pharmaceutical care: the PCNE definition 2013. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(3):544–555. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9933-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gammie T, Vogler S, Babar ZU. Economic evaluation of hospital and community pharmacy services. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(1):54–65. doi: 10.1177/1060028016667741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akinbosoye OE, Taitel MS, Grana J, et al. Improving medication adherence and health care outcomes in a commercial population through a community pharmacy. Popul Health Manag. 2016;19(6):454–461. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Central Statistical Office. Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/apteki-i-punkty-apteczne-w-2018-roku,15,3.html. Accessed August28, 2020.

- 16.Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Community Pharmacy Patient Questionnaire (CPPQ). Available from: https://psnc.org.uk/contract-it/essential-service-clinical-governance/cppq/. Accessed August28, 2020.

- 17.Merks P, Białoszewska K, Kozłowska – Wojciechowska M. Usługi farmaceutyczne w Polsce – profil korzystania oraz poziom satysfakcji pacjentów jako czynniki strategiczne przy wprowadzeniu pełnej opieki farmaceutycznej [Pharmaceutical services in Poland - the profile of use and the level of patient satisfaction as strategic factors in the implementation of full pharmaceutical care]. Farm Pol. 2012;68(12):812–819. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Arifi MN. Patient’s perception, views and satisfaction with pharmacists’ role as health care provider in community pharmacy setting at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2012;20(4):323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasan S, Sulieman H, Stewart K, et al. Assessing patient satisfaction with community pharmacy in the UAE using a newly validated tool. RSAP. 2013;9:841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horvat N, Kos M. Slovenian pharmacy performance: a patient – centred approach to patient satisfaction survey content development. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(6):985–996. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9572-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minarikova D, Malovecka I, Lehocka L, et al. The Assessment of Patient Satisfaction and Attendance of Community Pharmacies in Slovakia. Eur Pharm J. 2016;63(2):23–29. doi: 10.1515/afpuc-2016-0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minarikova D, Malovecka I, Foltan V. Patient choice of pharmacy and satisfaction with pharmaceutical care – slovak regional comparison. FARMACIA. 2016;64(3):473–480. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilugal K, Kaur MJ, Molugulu N, et al. Patient’s attitudes and satisfaction towards community pharmacy in Selangor, Malaysia. Le Pharmacie Hospitalier et Clinicien. 2016;51(3):210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.phclin.2015.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okumura LM, Rotta I, Correr CJ. Assessment of pharmacist-led patient counseling in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(5):882–891. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9982-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mináriková D, Fazekaš T, Minárik P, et al. Assessment of patient counselling on the common cold treatment at Slovak community pharmacies using mystery shopping. Saudi Pharm J. 2019;27(4):574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, et al. Effect of outpatient pharmacists’ non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(7):CD000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, et al. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adher. 2012;6:39–48. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S24752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Quteimat OM, Amer AM. Evidence-based pharmaceutical care: the next chapter in pharmacy practice. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(4):447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abrahamsen B, Burghle AH, Rossing C. Pharmaceutical care services available in Danish community pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(2):315–320. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-00985-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa FA, Scullin C, Al-Taani G, et al. Provision of pharmaceutical care by community pharmacists across Europe: is it developing and spreading? J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(6):1336–1347. doi: 10.1111/jep.12783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Świeczkowski D, Czogała K, Jeleniewska K, et al. Apteka w służbie zdrowia publicznego – konfrontacja stanu świadomości społecznej z aktualną sytuacją prawną na przykładzie województwa pomorskiego [Pharmacy in the public health service - confrontation of the state of social awareness with the current legal situation on the example of the Pomeranian Voivodeship]. Farm Pol. 2016;78(3):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malewski DF, Ream A, Gaither CA. Patient satisfaction with community pharmacy: comparing urban and suburban chain – pharmacy populations. RSAP. 2015;11:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pringle JL, Boyer A, Conklin MH, et al. The Pennsylvania Project: pharmacist intervention improved medication adherence and reduced health care costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1444–1452. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mossialos E, Courtin E, Naci H, et al. From “retailers” to health care providers: transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy (New York). 2015;119(5):628–639. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]