Abstract

Objectives

To assess the association of fluoroquinolone use with tendon ruptures compared with no fluoroquinolone and that of the four most commonly prescribed non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics in the USA.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

US seniors enrolled in the federal old-age, survivor’s insurance programme.

Participants

1 009 925 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries and their inpatient, outpatient, prescription drug records were used.

Interventions

Seven oral antibiotics, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) and amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin and cephalexin.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

All tendon ruptures combined, and three types of tendon ruptures by anatomic site, Achilles tendon rupture, rupture of rotator cuff and other tendon ruptures occurred in 2007–2016.

Results

Of three fluoroquinolones, only levofloxacin exhibited a significant increased risk of tendon ruptures—16% (HR=1.16; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.28), and 120% (HR=2.20; 95% CI 1.50 to 3.24) for rotator cuff and Achilles tendon rupture, respectively, in the ≤30 days window. Ciprofloxacin (HR=0.96; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.03) and moxifloxacin (HR=0.59; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.93) exhibited no increased risk of tendon ruptures combined.

Among the non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics, cephalexin exhibited increased risk of combined tendon ruptures (HR=1.31; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.41) and modest to large risks across all anatomic rupture sites (HRs 1.19–1.93) at ≤30 days window. Notably, the risk of levofloxacin never exceeded the risk of the non-fluoroquinolone, cephalexin in any comparison.

Conclusions

In our study, fluoroquinolones as a class were not associated with the increased risk of tendon ruptures. Neither ciprofloxacin nor moxifloxacin exhibited any risk for tendon ruptures. Levofloxacin did exhibit significant increased risk. Cephalexin with no reported effect on metalloprotease activity had an equal or greater risk than levofloxacin; so we question whether metalloprotease activity has any relevance to observed associations with tendon rupture. Confounding by indication bias may be more relevant and should be given more consideration as explanation for significant associations in observational studies of tendon rupture.

Keywords: clinical pharmacology, epidemiology, oral medicine, musculoskeletal disorders, accident & emergency medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a large (more than 1 million US senior subjects) retrospective study of outpatient prescription drug records to assess the association between the use of fluoroquinolones and the occurrence of tendon ruptures compared with the most commonly used non-fluoroquinolone oral antibiotics.

Our study included all oral fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) prescribed in the USA and the four most commonly prescribed non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics: amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin and cephalexin as controls.

In addition to reporting the risk of any tendon rupture, we also reported the risk of three types of tendon ruptures by anatomic site (1) Achilles tendon rupture, (2) rupture of rotator cuff and (3) tendon ruptures on other anatomic sites as separate outcomes.

This study is possibly only applicable to US senior, aged 65 or more, Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

We had no options to verify claims diagnoses via chart review.

Introduction

Fluoroquinolones (FQ) are among the most widely prescribed antibiotics in the outpatient setting1 2 due to their broad spectrum treatment of bacteria found in respiratory, urinary, joint, and skin infections. Several observational studies have reported the association between the use of FQs and tendinitis and tendon rupture (TR), especially of the Achilles tendon3–12 and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued black box warnings to FQ antibiotics beginning in 2008.13 The warning was updated in 2016 to recommend using alternative antibiotics when possible.14 15 The fact that FQs upregulate the production of metalloproteinase enzymes with collagenase activity that could weaken tendons is taken as a mechanism to explain this reported risk.16–18

Studies that reported association between FQ use and TR used one or more other antibiotics as controls. One study compared the FQ rupture rates with patients using azithromycin (AZT), the most frequently used oral antibiotic in the USA. Only two focused principally on TR risk among the elderly. None compared TR rates of FQs with those of cephalexin (LEX)—the third most commonly prescribed oral antibiotic in the USA.

The Virtual Research Data Center (VRDC) of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)19 carries more than 10 years of Medicare claims, which include information about the usage of prescription drugs and encounter diagnoses (including TRs). It also carries information about 42 major chronic conditions, demographic characteristic and vital status. We conducted a large observational study using the VRDC to assess the association of FQ antibiotics with TR compared with that of the four most commonly prescribed non-FQ antibiotics in the USA. Here, we report the results of that analysis.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in the design of the study.

Study population

We derived our study population from a 20% random sample of Medicare prescription drug coverage (part D) enrollees who first enrolled in the Medicare under old age and survivors insurance within a month of age 65 (779–781 month old) and on or after 1 January 2007, the first full year of part D prescriptions availability. We included claim data through 31 December 2016, the end of VRDC claim data available to us. All of the VRDC data are deidentified and researchers must perform all of their analysis within the VRDC computer systems, and can only pull statistical results from it.19 This study was declared not human subject research by the Office of Human Research Protection at the National Institutes of Health and by the CMS’s Privacy Board.

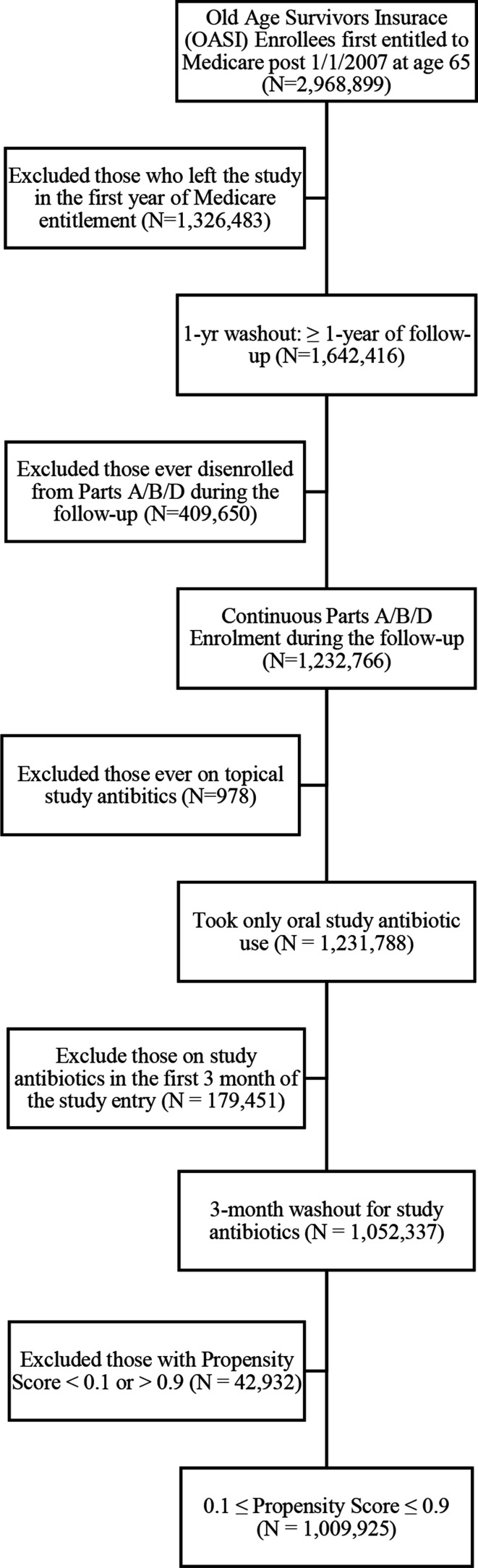

We required subjects to be continuously enrolled in hospital insurance (part A) and medical insurance (part B) to assure we had full outpatient and inpatient claims data, which are not available for nearly 20% of subjects with part D only.20 To obtain a cohort of patients with new TR, we excluded individuals with TRs recorded in the first year of their Medicare entitlement.21 In order to assure sufficient follow-up, we excluded individuals with less than 1-year follow-up. Moreover, to obtain incident (or new) drug user cohort, we excluded individuals who were prescribed any study antibiotics during their first 3 months after part D enrolment, while ignoring the data during the same time window for individuals not taking study antibiotics. By doing so, we minimise survivor bias from prevalent users (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

Primary outcome

We identified patients with TR based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9-CM codes of 726.13, 727.60–727.69, and ICD-10-CM codes of M66.2, M66.3, M66.8, M66.9 and M75.1. We combined all TRs and reported them as one outcome, and report three types of TRs by anatomic site (1) Achilles TR, (2) rupture of rotator cuff and (3) TRs on other anatomic sites as separate outcomes. We focused on Achilles TR because it was the sole focus of many prior studies and on rotator cuff TR because it is the predominant TR of the elderly. We lumped the remaining as ‘other TRs’.

Study antibiotics

We included a total of seven study antibiotics prescribed in the USA including all three oral FQs (moxifloxacin (MXF), ciprofloxacin (CIP), levofloxacin (LVX), the active stereoisomer of ofloxacin, and the four most frequently prescribed non-FQ oral antibiotics amoxicillin (AMX), amoxicillin clavulanate (AMC), AZT and LEX as controls. CIP and the four non-FQ, study antibiotics were the five most frequently used US oral antibiotics in 2011.

Statistical analysis

We analysed each of the four TR outcomes in separate Fine-Gray competing risk regression analyses with death as the competing risk.22 23 Individuals became eligible for ‘the study’ at their Medicare enrolment but prescription data did not become available until their part D enrolment. We followed them from their entry in part D (while accounting for left truncation24) until their first diagnosis of TR, death, switch to a capitated plan, disenrolment from Medicare or 31 December 2016—whichever came first. In each regression analysis, we included the seven antibiotics whose effects on TR were our primary interest. We adjusted HR of each study antibiotic for concurrent use of the other study antibiotics. We also adjusted for calendar year of individual’s part D entry, to account for secular trends, and their sociodemographic characteristics of gender, race, rural residency (yes/no) and income status. We inferred individual’s income level from the monthly indicators of dual eligibility and Low Income Subsidy (LIS) status, which separate subjects into three groups; (1) dual whose income is below 135% Federal Poverty Line (FPL); (2) non-dual LIS whose income is between 135% and 150% FPL; and (3) non-dual no LIS whose income is above 150% FPL, respectively. We used this variable in the analysis as a surrogate for economic status.25 We also included the 42 chronic conditions within the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File26 that had >1% prevalence as measures of overall health. We assumed that patients were on a given study drug from the prescription dispensing date to the end of days of supply. We did not distinguish between different brands of a study drugs. Following the approach of prior studies,3–5 we separated subjects by temporal exposure within each study drug, including groups for never exposed, exposed within 30 days, 31–60 days, and >60 days of the index (or TR event) time. Thus, by this approach, we could detect the presumed short-term action of the FQ’s on tendons and avoid the risk of non-differential misclassification that can occur with too simple (yes/no) drug exposure measures.27 In order to minimise the immortal time bias, we treated all drug usage measures and all sociodemographic characteristics, except gender, race and rural residency, as time-varying covariates.28 29 In order to mitigate selection bias towards use of any study antibiotics, we employed a propensity score (PS) approach.30 31 We first derived a PS of taking any of study antibiotics as a function of individual’s characteristics at the time of the first antibiotic use after part D entry from a multiple logistic regression. We used the median days to the first study antibiotic use in patients taking study antibiotics as the cut-off time for individuals not taking study antibiotics. We performed our analyses with an inverse propensity score weight (IPSW) excluding individuals with the PS below 0.1 and above 0.9, to mitigate poorer performance in the presence of a strong treatment-selection process.32 In post-hoc analyses, we also compared the risk of TR of each study antibiotics to that of every other study antibiotic on a pairwise basis.

Results

Study population and secular trend

From our 20% sample of part D enrollees, 1 009 925 individuals satisfied all our selection criteria including the washout of individuals with any antibiotic use in their first 3 months of part D enrolment (figure 1). Follow-up began with an individual’s enrolment in part D programme (median (IQR) 0 (0–122) days from the Medicare entitlement). We followed them for a median of 3.6 years (total 4 030 897 patient years) until their first diagnosis of TR (3.5%), death (4.6%), switch to a capitated plan (12.6%), disenrolment from Medicare (<1%) or study end on 31 December 2016 (79.3%), whichever came first. Patients had their first post enrolment claim with a diagnosis of TR at a median age of 68.5 (IQR 67.2–70.4). The proportions of non-Hispanic white, female and rural residents were 80.7%, 57.0% and 22.6% respectively. About a fifth of individuals received federal/state subsidies, that is, Medicaid coverage on top of Medicare (dual 16.1%) or assistance in paying their part D premium and coinsurance/copayment (non-dual LIS 2.7%). Among the 42 Medicare chronic conditions, hypertension (67.3%), hyperlipidaemia (68.4%), cataract (46.4%), rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis (36.6%), anaemia (30.4%), ischaemic heart disease (26.2%) and chronic kidney disease (17.9%) were the seven most prevalent (table 1).

Table 1.

Outcome, medical/medication use, diseases and patient characteristics by type of antibiotics

| Variable | Overall | FLQ | CIP | LVX | MXF | AMX | AZM | LEX | AMC | None |

| N | 1 009 925 | 328 654 | 234 994 | 155 991 | 14 728 | 259 125 | 308 985 | 195 731 | 179 616 | 356 364 |

| Tendon rupture | 34 880 (3.5) | 12 517 (3.8) | 8811 (3.7) | 5904 (3.8) | 770 (5.2) | 9636 (3.7) | 12 448 (4.0) | 8019 (4.1) | 6622 (3.7) | 10 169 (2.9) |

| Death | 46 468 (4.6) | 23 249 (7.1) | 14 821 (6.3) | 14 610 (9.4) | 2136 (14.5) | 9632 (3.7) | 14 608 (4.7) | 11 394 (5.8) | 9951 (5.5) | 13 645 (3.8) |

| Censored at HMO entry | 127 162 (12.6) | 27 573 (8.4) | 19 847 (8.4) | 11 142 (7.1) | 1571 (10.7) | 21 215 (8.2) | 26 140 (8.5) | 14 887 (7.6) | 12 674 (7.1) | 65 886 (18.5) |

| Censored at disenrolment | 145 (0.0) | 25 (0.0) | 13 (0.0) | 13 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 19 (0.0) | 27 (0.0) | 23 (0.0) | 16 (0.0) | 85 (0.0) |

| Censored at 31 December 2016 | 801 270 (79.3) | 265 290 (80.7) | 191 502 (81.5) | 124 322 (79.7) | 10 249 (69.6) | 218 623 (84.4) | 255 762 (82.8) | 161 408 (82.5) | 150 353 (83.7) | 266 579 (74.8) |

| Years of follow-up, median (total) | 3.6 (4 030 897) | 4.6 (1 620 894) | 4.8 (1 190 308) | 4.8 (789 849) | 6.0 (87 397) | 4.5 (1 274 357) | 4.6 (1 529 370) | 4.8 (1 000 459) | 4.6 (890 340) | 2.5 (1 067 731) |

| Tendon rupture, 1000 person years | 8.65 | 7.72 | 7.40 | 7.47 | 8.81 | 7.56 | 8.14 | 8.02 | 7.44 | 9.52 |

| Death, 1000 person years | 11.53 | 14.34 | 12.45 | 18.50 | 24.44 | 7.56 | 9.55 | 11.39 | 11.18 | 12.78 |

| Female | 575 885 (57.0) | 197 915 (60.2) | 146 745 (62.4) | 89 682 (57.5) | 8747 (59.4) | 151 383 (58.4) | 194 101 (62.8) | 113 308 (57.9) | 104 749 (58.3) | 191 069 (53.6) |

| White | 814 933 (80.7) | 274 785 (83.6) | 196 048 (83.4) | 131 725 (84.4) | 12 464 (84.6) | 215 101 (83.0) | 259 657 (84.0) | 167 825 (85.7) | 153 723 (85.6) | 271 906 (76.3) |

| Black | 75 930 (7.5) | 20 017 (6.1) | 14 286 (6.1) | 8893 (5.7) | 956 (6.5) | 15 622 (6.0) | 17 296 (5.6) | 9625 (4.9) | 9199 (5.1) | 35 023 (9.8) |

| Hispanic | 56 582 (5.6) | 17 044 (5.2) | 12 607 (5.4) | 7943 (5.1) | 628 (4.3) | 12 494 (4.8) | 14 805 (4.8) | 8976 (4.6) | 7802 (4.3) | 24 391 (6.8) |

| Asian | 26 336 (2.6) | 7316 (2.2) | 5362 (2.3) | 3144 (2.0) | 356 (2.4) | 7624 (2.9) | 7945 (2.6) | 3539 (1.8) | 3440 (1.9) | 10 437 (2.9) |

| Other | 36 144 (3.6) | 9492 (2.9) | 6691 (2.8) | 4286 (2.7) | 324 (2.2) | 8284 (3.2) | 9282 (3.0) | 5766 (2.9) | 5452 (3.0) | 14 607 (4.1) |

| Ever dual | 162 988 (16.1) | 54 055 (16.4) | 38 277 (16.3) | 28 156 (18.0) | 2908 (19.7) | 35 305 (13.6) | 44 940 (14.5) | 30 962 (15.8) | 25 255 (14.1) | 66 986 (18.8) |

| Non-dual LIS | 26 955 (2.7) | 7648 (2.3) | 5459 (2.3) | 3746 (2.4) | 385 (2.6) | 5224 (2.0) | 6828 (2.2) | 4191 (2.1) | 3818 (2.1) | 12 595 (3.5) |

| Non-dual No LIS | 819 982 (81.2) | 266 951 (81.2) | 191 258 (81.4) | 124 089 (79.5) | 11 435 (77.6) | 218 596 (84.4) | 257 217 (83.2) | 160 578 (82.0) | 150 543 (83.8) | 276 783 (77.7) |

| Living in rural area | 228 199 (22.6) | 78 581 (23.9) | 56 385 (24.0) | 38 847 (24.9) | 2801 (19.0) | 58 805 (22.7) | 72 282 (23.4) | 49 977 (25.5) | 42 288 (23.5) | 77 087 (21.6) |

| Days on Rx, median (IQR) | N/A | N/A | 10.0 (7.0–20.0) | 10.0 (7.0–17.0) | 10.0 (7.0–12.0) | 10.0 (7.0–20.0) | 5.0 (5.0–11.0) | 10.0 (7.0–16.0) | 10.0 (10.0–20.0) | N/A |

| Hospitalisation | 349 959 (29.5) | 198 846 (45.4) | 142 538 (45.3) | 113 829 (52.5) | 14 002 (60.3) | 132 304 (38.8) | 156 185 (37.9) | 119 209 (45.9) | 103 515 (42.5) | 51 525 (14.4) |

| Outpatient visits per year, median (IQR) | 19.6 (11.1–33.0) | 27.1 (17.2–42.7) | 27.3 (17.5–42.9) | 30.1 (19.0–47.8) | 34.0 (21.7–53.7) | 23.6 (14.5–37.5) | 24.6 (15.5–38.8) | 27.5 (17.2–43.2) | 26.6 (16.7–42.2) | 12.3 (6.0–21.8) |

| AMI | 21 222 (2.1) | 9999 (3.0) | 6810 (2.9) | 5862 (3.8) | 698 (4.7) | 6474 (2.5) | 8079 (2.6) | 6215 (3.2) | 5292 (2.9) | 5012 (1.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 71 635 (7.1) | 31 752 (9.7) | 21 757 (9.3) | 17 731 (11.4) | 2028 (13.8) | 23 974 (9.3) | 26 182 (8.5) | 21 935 (11.2) | 18 764 (10.4) | 16 314 (4.6) |

| Cataract | 468 608 (46.4) | 183 870 (55.9) | 134 196 (57.1) | 88 574 (56.8) | 9216 (62.6) | 144 455 (55.7) | 174 897 (56.6) | 112 020 (57.2) | 101 079 (56.3) | 124 931 (35.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 180 441 (17.9) | 86 021 (26.2) | 62 323 (26.5) | 46 121 (29.6) | 4651 (31.6) | 53 713 (20.7) | 65 577 (21.2) | 50 361 (25.7) | 43 182 (24.0) | 42 916 (12.0) |

| COPD | 130 840 (13.0) | 71 913 (21.9) | 43 961 (18.7) | 48 430 (31.0) | 6106 (41.5) | 40 109 (15.5) | 66 536 (21.5) | 37 413 (19.1) | 37 579 (20.9) | 22 739 (6.4) |

| Heartfailure | 103 010 (10.2) | 51 814 (15.8) | 34 870 (14.8) | 31 377 (20.1) | 3776 (25.6) | 32 792 (12.7) | 41 647 (13.5) | 31 585 (16.1) | 27 223 (15.2) | 21 907 (6.1) |

| Diabetes | 284 919 (28.2) | 113 424 (34.5) | 81 175 (34.5) | 57 697 (37.0) | 5942 (40.3) | 81 155 (31.3) | 98 176 (31.8) | 67 548 (34.5) | 59 984 (33.4) | 81 448 (22.9) |

| Glaucoma | 150 839 (14.9) | 56 990 (17.3) | 41 984 (17.9) | 26 603 (17.1) | 2930 (19.9) | 45 597 (17.6) | 54 726 (17.7) | 33 936 (17.3) | 31 065 (17.3) | 42 355 (11.9) |

| Hip/pelvic fracture | 7982 (0.8) | 4086 (1.2) | 3000 (1.3) | 2289 (1.5) | 274 (1.9) | 2673 (1.0) | 3005 (1.0) | 2515 (1.3) | 1914 (1.1) | 1689 (0.5) |

| Ischaemicheart disease | 264 648 (26.2) | 117 416 (35.7) | 82 182 (35.0) | 63 659 (40.8) | 6956 (47.2) | 83 682 (32.3) | 101 999 (33.0) | 70 612 (36.1) | 63 363 (35.3) | 63 372 (17.8) |

| Depression | 210 714 (20.9) | 94 554 (28.8) | 68 625 (29.2) | 49 277 (31.6) | 5298 (36.0) | 65 642 (25.3) | 83 253 (26.9) | 56 747 (29.0) | 51 150 (28.5) | 49 320 (13.8) |

| Alzheimer’s disease or senile dementia | 39 132 (3.9) | 19 796 (6.0) | 14 309 (6.1) | 11 030 (7.1) | 1206 (8.2) | 11 140 (4.3) | 13 809 (4.5) | 11 846 (6.1) | 9309 (5.2) | 9400 (2.6) |

| Osteoporosis | 106 966 (10.6) | 47 033 (14.3) | 35 217 (15.0) | 22 918 (14.7) | 2738 (18.6) | 34 610 (13.4) | 44 016 (14.2) | 26 996 (13.8) | 24 393 (13.6) | 25 216 (7.1) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis | 369 584 (36.6) | 160 091 (48.7) | 117 018 (49.8) | 80 115 (51.4) | 8259 (56.1) | 126 702 (48.9) | 148 653 (48.1) | 101 310 (51.8) | 88 017 (49.0) | 81 855 (23.0) |

| Stroke/ transient ischaemic attack | 58 886 (5.8) | 27 702 (8.4) | 19 843 (8.4) | 15 051 (9.6) | 1670 (11.3) | 17 829 (6.9) | 22 038 (7.1) | 16 684 (8.5) | 14 245 (7.9) | 14 262 (4.0) |

| Breast cancer | 45 316 (4.5) | 19 362 (5.9) | 14 344 (6.1) | 9442 (6.1) | 984 (6.7) | 13 451 (5.2) | 17 676 (5.7) | 12 543 (6.4) | 10 156 (5.7) | 11 042 (3.1) |

| Colorectal cancer | 15 905 (1.6) | 7487 (2.3) | 5421 (2.3) | 4048 (2.6) | 390 (2.6) | 4304 (1.7) | 5170 (1.7) | 4085 (2.1) | 3605 (2.0) | 4104 (1.2) |

| Prostate cancer | 37 038 (3.7) | 19 705 (6.0) | 15 577 (6.6) | 9232 (5.9) | 643 (4.4) | 10 967 (4.2) | 11 733 (3.8) | 9252 (4.7) | 8070 (4.5) | 8333 (2.3) |

| Lung cancer | 14 946 (1.5) | 8965 (2.7) | 5144 (2.2) | 6356 (4.1) | 905 (6.1) | 3859 (1.5) | 6633 (2.1) | 3977 (2.0) | 4267 (2.4) | 2733 (0.8) |

| Endometrial cancer | 7396 (0.7) | 3447 (1.0) | 2670 (1.1) | 1635 (1.0) | 160 (1.1) |

2095 (0.8) | 2637 (0.9) | 1957 (1.0) | 1604 (0.9) | 1847 (0.5) |

| Anaemia | 307 310 (30.4) | 140 606 (42.8) | 100 819 (42.9) | 74 308 (47.6) | 7980 (54.2) |

99 190 (38.3) | 118 327 (38.3) | 81 967 (41.9) | 72 587 (40.4) | 71 098 (20.0) |

| Asthma | 86 120 (8.5) | 46 350 (14.1) | 29 327 (12.5) | 30 152 (19.3) | 4091 (27.8) | 27 632 (10.7) | 46 823 (15.2) | 24 426 (12.5) | 25 465 (14.2) | 13 802 (3.9) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 691 148 (68.4) | 257 086 (78.2) | 185 199 (78.8) | 123 828 (79.4) | 12 162 (82.6) | 199 236 (76.9) | 239 414 (77.5) | 152 879 (78.1) | 140 364 (78.1) | 201 258 (56.5) |

| Hyperplasia | 122 010 (12.1) | 59 809 (18.2) | 45 517 (19.4) | 28 616 (18.3) | 2587 (17.6) | 39 031 (15.1) | 42 070 (13.6) | 31 606 (16.1) | 28 398 (15.8) | 27 336 (7.7) |

| Hypertension | 679 287 (67.3) | 253 601 (77.2) | 181 231 (77.1) | 124 646 (79.9) | 12 218 (83.0) | 192 686 (74.4) | 230 409 (74.6) | 150 995 (77.1) | 136 292 (75.9) | 201 777 (56.6) |

| Hypothyroidism | 197 447 (19.6) | 81 468 (24.8) | 59 450 (25.3) | 40 372 (25.9) | 4198 (28.5) | 59 893 (23.1) | 76 582 (24.8) | 47 973 (24.5) | 44 249 (24.6) | 50 280 (14.1) |

| Anxiety disorders | 148 983 (14.8) | 70 688 (21.5) | 51 377 (21.9) | 37 563 (24.1) | 4032 (27.4) | 48 859 (18.9) | 62 418 (20.2) | 41 655 (21.3) | 37 588 (20.9) | 31 709 (8.9) |

| Bipolar disorder | 17 882 (1.8) | 8368 (2.5) | 6104 (2.6) | 4533 (2.9) | 468 (3.2) | 5442 (2.1) | 6658 (2.2) | 5147 (2.6) | 4227 (2.4) | 4242 (1.2) |

| Major depressive affective disorder | 153 182 (15.2) | 71 732 (21.8) | 52 101 (22.2) | 38 055 (24.4) | 4148 (28.2) | 48 846 (18.9) | 61 872 (20.0) | 43 416 (22.2) | 38 642 (21.5) | 33 660 (9.4) |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | 16 764 (1.7) | 8591 (2.6) | 6176 (2.6) | 4934 (3.2) | 548 (3.7) | 4421 (1.7) | 5597 (1.8) | 5101 (2.6) | 3811 (2.1) | 4300 (1.2) |

| Epilepsy | 16 155 (1.6) | 7543 (2.3) | 5383 (2.3) | 4269 (2.7) | 415 (2.8) | 4310 (1.7) | 5488 (1.8) | 4510 (2.3) | 3621 (2.0) | 4191 (1.2) |

| Fibromyalgia, chronic pain and fatigue | 166 279 (16.5) | 78 877 (24.0) | 57 494 (24.5) | 41 843 (26.8) | 4410 (29.9) | 56 152 (21.7) | 70 667 (22.9) | 48 422 (24.7) | 43 379 (24.2) | 33 843 (9.5) |

| Viral hepatitis (general) | 11 969 (1.2) | 4659 (1.4) | 3188 (1.4) | 2523 (1.6) | 287 (1.9) | 3156 (1.2) | 3732 (1.2) | 2712 (1.4) | 2348 (1.3) | 3735 (1.0) |

| Liver disease cirrhosis and other liver conditions | 62 675 (6.2) | 31 930 (9.7) | 23 284 (9.9) | 17 386 (11.1) | 1919 (13.0) | 19 624 (7.6) | 24 544 (7.9) | 17 393 (8.9) | 15 958 (8.9) | 13 350 (3.7) |

| Leukaemias and lymphomas | 13 906 (1.4) | 7228 (2.2) | 4822 (2.1) | 4536 (2.9) | 551 (3.7) | 4385 (1.7) | 5905 (1.9) | 4025 (2.1) | 3969 (2.2) | 2758 (0.8) |

| Migraine and other chronic headache | 31 628 (3.1) | 14 936 (4.5) | 11 282 (4.8) | 7520 (4.8) | 873 (5.9) | 10 841 (4.2) | 13 893 (4.5) | 8763 (4.5) | 8403 (4.7) | 6419 (1.8) |

| Mobility impairments | 20 600 (2.0) | 10 182 (3.1) | 7356 (3.1) | 5767 (3.7) | 577 (3.9) | 5372 (2.1) | 6629 (2.1) | 5995 (3.1) | 4610 (2.6) | 5439 (1.5) |

| Obesity | 185 101 (18.3) | 79 130 (24.1) | 56 609 (24.1) | 41 226 (26.4) | 3997 (27.1) | 58 654 (22.6) | 69 611 (22.5) | 49 984 (25.5) | 43 740 (24.4) | 44 772 (12.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 90 132 (8.9) | 45 276 (13.8) | 31 866 (13.6) | 25 977 (16.7) | 3001 (20.4) | 28 747 (11.1) | 36 241 (11.7) | 28 343 (14.5) | 23 977 (13.3) | 18 446 (5.2) |

| Tobacco use disorders | 101 890 (10.1) | 45 304 (13.8) | 28 907 (12.3) | 27 202 (17.4) | 3042 (20.7) | 27 261 (10.5) | 37 860 (12.3) | 25 002 (12.8) | 22 975 (12.8) | 26 896 (7.5) |

| Pressure ulcers and chronic ulcers | 30 345 (3.0) | 17 688 (5.4) | 12 800 (5.4) | 10 603 (6.8) | 1196 (8.1) | 9006 (3.5) | 10 926 (3.5) | 13 404 (6.8) | 9960 (5.5) | 4992 (1.4) |

| Deafness and hearing impairment | 59 576 (5.9) | 27 383 (8.3) | 19 976 (8.5) | 14 014 (9.0) | 1609 (10.9) | 21 213 (8.2) | 25 498 (8.3) | 16 849 (8.6) | 16 787 (9.3) | 11 900 (3.3) |

Data are presented as no. (%) of patients unless otherwise noted.

AMC, amoxicillin clavulanate; AMX, amoxicillin; AZT, azithromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; FLQ, fluoroquinolone; LEX, cephalexin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin.

Of the 328 654 (33.0%) patients who ever took an FQ, 71.5%, 47.5% and 4.5% had taken CIP, LVX and MXF, respectively. Of 576 885 (57.1%) of patients who ever took a non-FQ antibiotic, the figures were 53.6%, 44.9%, 33.9% and 31.1% for AZM, AMX, LEX and AMC, respectively. Patients who took one or more study antibiotics took a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.0–6.0) study antibiotic prescriptions and took a median (IQR) 2.0 (1.0–3.0) different study antibiotics during the observation period. About 2.5% patients who took one or more study antibiotics took one or more such antibiotics at the same time.

Secular trends in study antibiotics usage existed (see online supplemental figure 1). MXF usage declined precipitously from 5.0% in 2007 to almost zero in 2016—overweighting the MXF statistics for early entrants into Medicare and yielding a longer mean follow-up time. CIP use hit a peak, and LVX, a nadir, in 2011. The use of AMX, AMC and LEX trended slowly upward (see online supplemental figure 1). The mode (median) of supply durations for each antibiotics was short—10 (7) for AMX, 10 (10) for AMC, 5 (5) for AZM, 10 (7) for LEX, 7 (7) for CIP, 10 (7) for LVX, 10 (11) for MXF. About 35% of individuals were never exposed to any of the study antibiotics during the study period.

bmjopen-2019-034844supp001.pdf (12.5MB, pdf)

Unadjusted figures for TR prevalence across each of the seven study antibiotic users and the no study antibiotic users ranged from a high of 5.2% for MXF to a low of 2.9% for no antibiotic (table 1). Except for MXF, the unadjusted prevalence of TRs associated with each non-FQ antibiotic was greater than or equal to that of each FQ antibiotic. The TR rates per 1000 patient years followed the same pattern, with the non-FQ antibiotics topping the rates of all FQs except MXF (with the highest rate), possibly due to overweighting of MXF usage in the early years of the study. Patients who ever took an FQ had the highest unadjusted rate of death per 1000 person years. LVX’s death rate was nearly twice the rate of each non-FQ antibiotics. The size of the associations with conditions like diabetes, chronic renal failure and heart failure paralleled the magnitude of the death rates and was generally higher with FQs than non-FQ antibiotics (table 1).

Primary analysis

Table 2 presents HRs for all non-antibiotic covariates in our Fine-Gray competing risk regression with IPSW. For simplicity sake, in table 2, we report the HRs of all anatomic types of TRs taken together. Being a female (vs male), African-American, Hispanic, and Asian (vs white), being dual or non-dual LIS (vs non-dual no LIS) and living in a rural area were all associated with a reduced risk of TR. These risk reductions were 24% or more for all but Hispanics and rural residency covariates, and the reductions were similar across all anatomic sites. In general, life-threatening chronic conditions, such as Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), heart failure and colorectal/lung/endometrial cancers were associated with a lower risk of TR in a range of 15%–60% below control possibly due to constrained physical activity and/or shortened life span. Notably, diabetes and chronic renal disease, previously reported as risk factors for TR,33 34 exhibited no increased TR risk. Mobility impairments had reduced risk of TR similar to that of the severe life-threatening conditions, likely due to reduced activity. Most conditions with low life threats such as cataract, glaucoma, depression, asthma, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, prostatic hyperplasia, migraine/other chronic headache, and deafness/hearing impairment exhibited risks of 8% to 34% above controls probably for reasons related to longer life spans and less inhibited activity. Ischaemic heart did not fit the mould of sicker equals lower TR risk. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis were a special case and had TR risk of 184% above control possibly due to joint and associated tendon inflammation with these disorders. Fibromyalgia/chronic pain and fatigue also exhibited a 39% increased risk of TR possibly also due to an inflammatory component.

Table 2.

HRs of tendon rupture for each covariate

| Variables | Reference | HR (95% CI) |

| Female | Male | 0.70 (0.69 to 0.72)↡ |

| Black | White | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.78)↡ |

| Hispanic | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.94)↡ | |

| Asian | 0.67 (0.63 to 0.71)↡ | |

| Other | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09)↑ | |

| Dual ever | Non-Dual Non-LIS | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.68)↡ |

| Non-dual lis | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.70)↡ | |

| Living in rural area | No | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.95)↡ |

| Medicare part d since 2008 | Medicare Part D Since 2007 | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) |

| Medicare part d since 2009 | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15)↟ | |

| Medicare part d since 2010 | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.21)↟ | |

| Medicare part d since 2011 | 1.17 (1.13 to 1.22)↟ | |

| Medicare part d since 2012 | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16)↟ | |

| Medicare part d since 2013 | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) | |

| Medicare part d since 2013 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09)↑ | |

| Medicare part d since 2015 | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.96)↡ | |

| Medicare part d since 2016 | 0.93 (0.19 to 4.55) | |

| AMI | No | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79)↡ |

| Atrial fibrillation | No | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97)↡ |

| Cataract | No | 1.23 (1.21 to 1.25)↟ |

| Chronic kidney disease | No | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.94)↡ |

| COPD | No | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.86)↡ |

| Heart failure | No | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.82)↡ |

| Diabetes | No | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99)↓ |

| Glaucoma | No | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.12)↟ |

| Hip/pelvic fracture | No | 0.68 (0.60 to 0.77)↡ |

| Ischaemic heart disease | No | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.12)↟ |

| Depression | No | 1.17 (1.13 to 1.21) |

| Alzheimer’s disease or senile dementia | No | 0.67 (0.63 to 0.71)↡ |

| Osteoporosis | No | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06)↑ |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis | No | 2.84 (2.80 to 2.89)↟ |

| Stroke/transient ischaemic attack | No | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.01) |

| Breast cancer | No | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98)↓ |

| Colorectal cancer | No | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.85)↡ |

| Prostate cancer | No | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) |

| Lung cancer | No | 0.39 (0.34 to 0.45)↡ |

| Endometrial cancer | No | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.94)↓ |

| Anaemia | No | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Asthma | No | 1.27 (1.24 to 1.31)↟ |

| Hyperlipidaemia | No | 1.34 (1.31 to 1.36)↟ |

| Hyperplasia | No | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.16)↟ |

| Hypertension | No | 1.09 (1.07 to 1.11)↟ |

| Hypothyroidism | No | 1.08 (1.06 to 1.10)↟ |

| Anxiety disorders | No | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) |

| Bipolar disorder | No | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.08) |

| Major depressive affective disorder | No | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10)↑ |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | No | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.74)↡ |

| Epilepsy | No | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.90)↡ |

| Fibromyalgia, chronic pain and fatigue | No | 1.39 (1.36 to 1.42)↟ |

| Viral hepatitis (general) | No | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.13) |

| Liver disease cirrhosis and other liver conditions | No | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.99)↓ |

| Leukaemias and lymphomas | No | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.01) |

| Migraine and other chronic headache | No | 1.28 (1.23 to 1.33)↟ |

| Mobility impairments | No | 0.70 (0.65 to 0.76)↡ |

| Obesity | No | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06)↑ |

| Peripheral vascular disease | No | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.04) |

| Tobacco use disorders | No | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.85)↡ |

| Pressure ulcers and chronic ulcers | No | 0.82 (0.77 to 0.87)↡ |

| Deafness and hearing impairment | No | 1.21 (1.17 to 1.25)↟ |

HRs and CIs from the primary analysis for covariates except for the study antibiotics (which are in table 3).

↟=very significantly increasedwith P value<0.001, ↑=significantly high with 0.001≤ p<0.05.

↡=very significantly decreased with P value<0.001, ↓=significantly decrease with 0.001≤ p<0.05.

AMC, amoxicillin clavulanate; AMX, amoxicillin; AZT, azithromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; FLQ, fluoroquinolone; LEX, cephalexin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin.

The Achilles tendon carries the full force of the extra weight carried by obese patients and obesity was associated with a significant (13%) increase in Achilles TR ruptures while its effect on other TR classes was significant but minuscule (2%–3%) (data not shown).

Effect of antibiotics

We report HRs from our primary analysis in tables separate from the non-antibiotic covariates. Table 3 shows the risk associated with each study antibiotic broken down by time lag between the antibiotic use and the TRs (separate rows), and by all TRs together and separately by anatomic sites (in columns). We also report HRs of death (competing risk). We used multiplicity corrected p values to simultaneously test the difference of pairs of antibiotics to minimise the chance of finding statistically significant difference by random chance.35 Of the total 34 880 patients with any TR occurrence, complete rupture of rotator cuff represented the major share (80.5%), followed by other TRs (16.9%) and Achilles TR (2.6%). In the survival analysis, we followed patients until the first occurrence of TR; so, these figures count only the first TR occurrence independent of anatomic site.

Table 3.

HRs of each antibiotic by anatomic sites and temporal order of drug exposure

| Temporal exposure | Any tendon rupture | Achilles tendon rupture | Complete rupture of rotator cuff | Other tendon ruptures | Death (competing risk) | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| AMX versus NO AMX | ≤30 days | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.92) ↡ | 0.88 (0.59 to 1.33) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95) ↓ | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.93) ↓ | 0.66 (0.61 to 0.71) ↡ |

| 31–60 days | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.01) | 0.80 (0.49 to 1.31) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) ↓ | 1.08 (0.93 to 1.27) | 0.69 (0.63 to 0.75) ↡ | |

| ≥61 days | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.01) | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.78) ↡ | |

| AMC versus NO AMC | ≤30 days | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.02) | 1.25 (0.79 to 1.97) | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.97) ↓ | 1.17 (0.98 to 1.41) | 1.37 (1.30 to 1.45) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.05) | 1.37 (0.82 to 2.29) | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.06) | 0.81 (0.63 to 1.04) | 1.26 (1.17 to 1.35) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09) ↟ | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.12) | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10) ↟ | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) ↡ | |

| AZM versus NO AZM | ≤30 days | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.63) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 0.87 (0.75 to 1.01) | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.84) ↡ |

| 31–60 days | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.98) ↓ | 0.99 (0.65 to 1.49) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) ↓ | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.11) | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.82) ↡ | |

| ≥61 days | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.09) ↟ | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | 1.09 (1.07 to 1.12) ↟ | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.72) ↡ | |

| LEX versus NO LEX | ≤30 days | 1.31 (1.22 to 1.41) ↟ | 1.93 (1.35 to 2.75) ↟ | 1.19 (1.09 to 1.29) ↟ | 1.79 (1.56 to 2.06) ↟ | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.10) |

| 31–60 days | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.15) | 1.14 (0.66 to 1.96) | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.18) | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.26) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08) | |

| ≥61 days | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.11) ↟ | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.16) | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10) ↟ | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) ↟ | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) ↡ | |

| LVX versus NO LVX | ≤30 days | 1.14 (1.05 to 1.25) ↑ | 2.20 (1.50 to 3.24) ↟ | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.28) ↑ | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.19) | 2.19 (2.11 to 2.28) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.21) | 1.91 (1.17 to 3.10) ↑ | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.22) | 1.14 (0.90 to 1.43) | 1.80 (1.71 to 1.89) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05) | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.43) ↑ | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) ↑ | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.03) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | |

| CIP versus NO CIP | ≤30 days | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.03) | 1.06 (0.70 to 1.60) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.04) | 0.84 (0.71 to 1.00) ↓ | 1.46 (1.40 to 1.53) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.01) | 1.02 (0.63 to 1.67) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) ↓ | 0.95 (0.78 to 1.14) | 1.31 (1.24 to 1.38) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) ↡ | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.32) ↑ | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.99) ↓ | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.97) ↓ | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) ↡ | |

| MXF versus NO MXF | ≤30 days | 0.59 (0.37 to 0.93) | 0.97 (0.15 to 6.24) | 0.52 (0.30 to 0.91) ↓ | 0.76 (0.33 to 1.77) | 2.05 (1.78 to 2.35) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.71 (0.43 to 1.15) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.13) | 0.93 (0.39 to 2.25) | 1.43 (1.18 to 1.72) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 1.02 (0.69 to 1.51) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.27) | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.93) ↡ | |

| FLQ versus AMX | ≤30 days | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.19) | 1.49 (0.69 to 3.19) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.16) | 1.08 (0.77 to 1.50) | 2.86 (2.61 to 3.13) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.15) | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.12) ↡ | 0.94 (0.75 to 1.17) | 0.92 (0.65 to 1.31) | 2.18 (1.96 to 2.44) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 1.14 (0.94 to 1.40) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.02) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.11) | 1.19 (1.16 to 1.22) ↟ | |

| FLQ versus AZM | ≤30 days | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | 1.14 (0.54 to 2.39) | 0.83 (0.68 to 1.02) | 0.98 (0.70 to 1.37) | 2.35 (2.18 to 2.53) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.19) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.09) ↡ | 0.93 (0.75 to 1.16) | 1.06 (0.75 to 1.49) | 1.94 (1.77 to 2.13) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.96) ↡ | 1.10 (0.91 to 1.34) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) ↡ | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 1.29 (1.25 to 1.32) ↟ | |

| FLQ versus LEX | ≤30 days | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.78) ↡ | 0.68 (0.32 to 1.42) | 0.70 (0.57 to 0.87) ↓ | 0.47 (0.34 to 0.66) ↡ | 1.80 (1.67 to 1.95) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.85 (0.70 to 1.04) | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.09) ↡ | 0.80 (0.64 to 1.01) | 0.99 (0.68 to 1.44) | 1.48 (1.34 to 1.64) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.95) ↡ | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.40) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.96) ↡ | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.93) ↡ | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09) ↟ | |

| FLQ versus AMC | ≤30 days | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.11) | 1.05 (0.48 to 2.32) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.19) | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.02) | 1.37 (1.27 to 1.48) ↟ |

| 31–60 days | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.15) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.07) ↡ | 0.90 (0.72 to 1.14) | 1.24 (0.83 to 1.86) | 1.19 (1.08 to 1.31) ↟ | |

| ≥61 days | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.97) ↡ | 1.19 (0.95 to 1.49) | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.96) ↡ | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.06) | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09) ↟ |

↟=very significantlyincreased with p <0.001, ↑=significantly increased with 0.001≤ p <0.05.

↡=very significantly decreased with p <0.001, ↓=significantly decreased with 0.001≤ p <0.05.

AMC, amoxicillin clavulanate; AMX, amoxicillin; AZT, azithromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; FLQ, fluoroquinolone; LEX, cephalexin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin.

Of the non-FQ antibiotics, AMX exhibited a reduced risk of TR compared with no AMX in every tendon class and time window, similar to its low risk in previous studies. It exhibited a significantly lower risk in the ≤30 days window except for the Achilles tendon. AZM and AMC exhibited a similar benign risk in all time windows except for TR of rotator cuff in >60 days window. LEX was the surprise non-FQ antibiotic. It exhibited modest to large increased TR risk at ≤30 days window across all sites ranging from a low of 19% increase for complete rupture of rotator cuff to a high 93% increase for Achilles TR. Its risk was also significantly higher at ≤30 days window for all TRs taken together.

Of the FQs, CIP and MXF, the most and least frequently prescribed FQ exhibited little to no increased risk of TR within each anatomic site and each time frame. LVX is the only FQ to exhibit a significant increase in TR risk—of 16%, and 120% for rupture of rotator cuff and Achilles TR, respectively, in the ≤30 days window. Notably, the risk of LVX never exceeded the risk of the non-FQ, LEX in any comparison.

In a post-hoc analysis (table 4), we compared the TR risk of each antibiotic with every other antibiotic (pairwise comparisons of FQ vs FQ and FQ vs non-FQ), for ≤30 days window and FQs as a class versus each non-FQ after combining the data from the three time windows. These results paralleled the above-mentioned risk for each study antibiotic in table 3. Again, TR risk for LVX was greater than that of CIP, MXF, AMC, AMX and AZM in a ≤30 days window. However, LVX risk was comparable to that of LEX for Achilles TR, and rupture of rotator cuff and significantly lower than LEX for the other TR classes. When comparing the risk of FQs as a class against that of non-FQ antibiotics, most of the non-FQ antibiotics had significantly greater risk than the FQ class as a whole across all TR sites (see last 4 rows of table 4).

Table 4.

Pairwise comparisons

| Comparison | Temporal exposure | Any tendon rupture | Achilles tendon rupture | Complete rupture of rotator cuff | Other tendon rupture | Death (competing risk) |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| HRs comparing use of each FQ with use of each non-FQ antibiotics in a ≤30 days window | ||||||

| CIP versus LVX | ≤30 days | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.94)↓ | 0.48 (0.27 to 0.86) ↓ | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.94) ↓ | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.15) | 0.67 (0.63 to 0.71)↡ |

| CIP versus MXF | ≤30 days | 1.63 (1.02 to 2.61)↑ | 1.08 (0.16 to 7.29) | 1.84 (1.05 to 3.24)↑ | 1.10 (0.47 to 2.60) | 0.72 (0.62 to 0.83)↡ |

| LVX versus MXF | ≤30 days | 1.95 (1.21 to 3.13)↑ | 2.26 (0.34 to 15.17) | 2.24 (1.27 to 3.94)↑ | 1.26 (0.53 to 3.01) | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.24) |

| CIP versus AMX | ≤30 days | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.23)↑ | 1.20 (0.66 to 2.16) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.21) | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) | 2.23 (2.05 to 2.44)↟ |

| CIP versus AZM | ≤30 days | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.06) | 0.91 (0.53 to 1.57) | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.07) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.21) | 1.84 (1.71 to 1.97)↟ |

| CIP versus LEX | ≤30 days | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.81)↡ | 0.55 (0.31 to 0.95) ↓ | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.91)↡ | 0.47 (0.37 to 0.59)↟ | 1.41 (1.31 to 1.52)↟ |

| CIP versus AMC | ≤30 days | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16) | 0.84 (0.46 to 1.56) | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.25) | 0.71 (0.56 to 0.92)↓ | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.15) |

| LVX versus AMX | ≤30 days | 1.33 (1.19 to 1.49)↟ | 2.50 (1.45 to 4.29)↑ | 1.32 (1.16 to 1.49)↟ | 1.22 (0.93 to 1.59) | 3.34 (3.07 to 3.64)↟ |

| LVX versus AZM | ≤30 days | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29)↑ | 1.91 (1.13 to 3.23)↑ | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.31)↑ | 1.10 (0.84 to 1.44) | 2.75 (2.57 to 2.95)↟ |

| LVX versus LEX | ≤30 days | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.98) ↓ | 1.14 (0.68 to 1.92) | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.12) | 0.54 (0.41 to 0.69)↟ | 2.11 (1.97 to 2.27)↟ |

| LVX versus AMC | ≤30 days | 1.23 (1.08 to 1.40)↑ | 1.76 (0.98 to 3.15) | 1.33 (1.15 to 1.54)↟ | 0.82 (0.62 to 1.08) | 1.60 (1.49 to 1.72)↟ |

| MXF versus AMX | ≤30 days | 0.68 (0.43 to 1.09) | 1.10 (0.16 to 7.41) | 0.59 (0.34 to 1.03) | 0.96 (0.41 to 2.27) | 3.12 (2.67 to 3.65)↟ |

| MXF versus AZM | ≤30 days | 0.59 (0.37 to 0.94) ↓ | 0.84 (0.13 to 5.65) | 0.52 (0.30 to 0.91)↓ | 0.88 (0.37 to 2.07) | 2.57 (2.21 to 2.98)↟ |

| MXF versus LEX | ≤30 days | 0.45 (0.28 to 0.72) ↓ | 0.50 (0.08 to 3.35) | 0.44 (0.25 to 0.77)↓ | 0.43 (0.18 to 1.00) | 1.97 (1.70 to 2.‡29)↟ |

| MXF versus AMC | ≤30 days | 0.63 (0.39 to 1.01) | 0.78 (0.11 to 5.33) | 0.60 (0.34 to 1.05) | 0.65 (0.28 to 1.53) | 1.50 (1.29 to 1.73)↟ |

| HRs comparing use of FQ as a class with use of each non-FQ antibiotics across different time window | ||||||

| FLQ versus AMX | Overall | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.07) | 0.49 (0.36 to 0.68) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.06) | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.19) | 1.95 (1.86 to 2.05)↟ |

| FLQ versus AZM | Overall | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.01) | 0.42 (0.30 to 0.57) | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.98)↓ | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.19) | 1.80 (1.73 to 1.88)↟ |

| FLQ versus LEX | Overall | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.88) | 0.34 (0.24 to 0.47) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) | 0.74 (0.62 to 0.88) | 1.42 (1.35 to 1.48)↟ |

| FLQ versus AMC | Overall | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.02) | 0.37 (0.26 to 0.52) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.03) | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.15) | 1.20 (1.15 to 1.25)↟ |

↟=very significantly increased with p<0.001, ↑=significantly increased with 0.001≤ p<0.05.

↡=very significantly decreased with p<0.001, ↓=significantlydecrease with 0.001≤ p<0.05.

AMC, amoxicillin clavulanate; AMX, amoxicillin; AZT, azithromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; FQ, fluoroquinolones; LEX, cephalexin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin.

In another analysis evaluating risk of death for each antibiotics, each FQ antibiotic exhibited a significant increase in death risk of : 46% (for CIP), 105% (for MXF) and 119% (for LVX) in a ≤30 days window. Among non-FQ antibiotics, only AMC exhibited 37% increased risk of death in a ≤30 days window. Overall, risk of death for FQs as a class far outweighed that of each non-FQ antibiotics.

Discussion

Our results conflict with the common assertion that the Achilles TR is the most common TR (up to 90% in one report36). In our elderly cohort, Achilles TRs were a tiny, 2.6%, of all TRs. Some of this difference may be explained by the differences in demographics. Reports of high prevalence of Achilles TR came from studies of young military populations.37 38 In contrast, our data came from an elderly Medicare population. Some of the difference could also be due to less ability to diagnose non-Achilles TRs until MRI joint imaging became widely available, because such TRs are less amenable to diagnosis by physical exam.

Many authorities describe the relationship between FQs and TRs as a class ‘effect’. However, FQs as a class had no significant risk of TR compared with each of the four non-FQ antibiotics in any time window. CIP (n=2 34 994 subjects) is the oral FQ with the greatest use and with a greater effect on metalloproteases than other FQs.39–41 However, neither MXF (n=14 728 subjects) nor CIP had any TR risk at any anatomic site in any time window. CIP’s lack of risk is consistent with two studies5 9 in which CIP exhibited zero risk or small risks compared with ofloxacin, a racemic mixture whose active ingredient is the levo-isomer, LVX. We do see a strong association between LVX and TRs whether we used no LVX or three of the non-FQ antibiotics as controls. However, when we used LEX, a cephalosporin, as the control for LVX’s effect on TRs, we saw no increased risk.

As noted in the introduction, the FDA has added a black box warning about TRs to the labels of FQs. A 2015 paper42 described the evidence for this decision based on the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database and an empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM) score, which is based on the relative frequency of spontaneous report about a given adverse event in one drug vs the reporting of that adverse event across all drugs. This EBGM score based on FAERS database has been useful but FAERS database is still limited by a lack of true denominator for population at risk, under-reporting due to a voluntary reporting scheme and bias due to limited adjustment variables.43 Our study was based on a well-defined Medicare population with 80 variable adjustments. The fact that LVX’s EBGM score was six times that of ofloxacin42 though both drugs have the same active ingredient (the levo-isomer of ofloxacin) and the same dose of that ingredient, raises questions about what factors influenced that score.

One previous study described the effect of FQs on TR risk as small and unimportant.10 Two studies reported no effect of FQs on TR risk.9 11 At least seven observational studies reported that the use of FQs increased risks of TR.3–8 12 However, in all but one study, the number of TRs among patients taking an FQs was small (between 5 and 111). In comparison, our study included 12 517 (3.8%) such patients. One previous study did report a large number of TR events, 23 000 (3.5%) patients while on FQs and, like our study, it focused exclusively on elderly patients.3 However, it did not compare the population of FQ users against non-users but FQ usage periods against non-usage periods in the same set of patients, which were likely periods without visits and thus could not account for the effect of increased clinical attention provided at visits requiring a strong systemic antibiotic. Furthermore, they assessed the association between AMX and TRs in separate analysis and used the risk of TRs in that analysis as the comparator for the risk observed in the FQ analysis. Finally, their analysis did not include death as a competing risk as is recommend when death rates exceed event rates23 which was likely the case because in the demographics of their study was very similar to ours.

In our study, AMX treated patients exhibited a similar absolute risk of TR as to LVX treated patients (7.56 vs 7.47 per 1000 patient years). However, they had fewer comorbidities (as in Daneman’s study), almost 14% fewer hospitalisations and half of death rate, compared with patients taking LVX (7.56 vs 18.50 per 1000 patient years). So, the two populations are not comparable. LVX exhibited 119% increased risk of death in a≤30 days window. They appears to be reserved for more severe infections or more fragile patients and thus subject to differential biases.

The reported activation of metalloprotease activity by FQs has underpinned the idea of a causal link between FQs and TRs. The argument goes as follows: FQs stimulate metalloproteases, which can break down collagen; the tendon is made of collagen; so FQs may cause TRs. However, our data disrupt this argument. CIP, which strongly stimulates metalloprotease activity,17 18 exhibited no risk of TRs in our study, and LEX which inhibits metalloprotease activity44 45 exhibited a large risk. So, we have to question whether metalloprotease activity has any relevance to TR risk, and consider other explanations for the observed associations.

The indication for an antibiotic is a presumed bacterial infection. The reported associations between antibiotics and TR could be a consequence of the indication (infection) rather than the antibiotic use to treat it. It could be a perfects example of the confounding by indication.46 Such a bias could explain many reported associations between drugs and TR risk including associations with non-antibiotic drugs reported by Nyyssönen et al.8

This indication (and infection) bias could generate an association between the antibiotic and TRs in different ways. First, the bacterial infection might directly increase the risk of TR via stimulation of general immune or cytokine responses, or even by direct bacterial invasion. A recent study found gram-positive bacteria in a major share of ruptured tendons but not in ‘control’ tendons removed surgically for grafting.47 So, the possibility of direct invasion of tendons by circulating bacteria with subsequent weakening and rupture is plausible.

Second, the greater clinical attention likely focused on patients needing systemic antibiotics, especially those with more severe infections, could increase the chance of noticing and documenting a pre-existing TR. A reservoir of not-yet-diagnosed such cases is likely to exist, because patients do not necessarily correctly identify joint and extremity symptoms as TRs and seek immediate care for them. TRs of the shoulder capsule, for example, are notorious for developing symptoms slowly over 2–3 years48 before being correctly diagnosed. Even Achilles TRs can be missed (in 30% of cases) at the first presentation.49 Seeger et al reviewed the medical records of patients with an insurance claim reporting TRs following antibiotic use and found that nearly half of the TRs recorded in the claims were either something else (eg, Bursa inflammation miscoded as a TR) or had occurred pre antibiotic use but only seen in a claim post antibiotic use.11

Indication bias is a plausible explanations for associations reported in observational studies and it should be considered more often before assuming the associations are causal.

Limitation

This study faces all of the limitations of observational studies. Furthermore, it applies only to fee-for-service Medicare populations. In addition, we had no options to verify claims diagnoses via chart review. From a statistical point of view, our findings may have some limitations. First, we included 80 covariates in one analysis and concern about intercorrelation affecting the validity could exist. To evaluate the intercorrelation, we calculated an 80×80 correlation matrix of estimated regression which can deliver information about the strength of intercorrelation and indicate the existence of a collinear relationship between two predictors. All pairwise correlations (except diagonal elements) were below 0.5, and the largest was 0.33 indicating minimal bias due to intercorrelation. We also did not consider interactions among covariates in our main analysis because of the problem of overfitting. We ran four sensitivity analyses with interaction terms between the study medications and four covariates (rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis, obesity, female sex, lung cancer). The inclusion of interactions did not change our conclusion of no TR risk for FQ as a class.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Jason Lau was with National Institutes of Health (NIH) during this work and now he is with the UC Davis Health. This work was partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. This research was made possible through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Genentech, the American Association for Dental Research, the Colgate-Palmolive Company, Elsevier, alumni of student research programs, and other individual supporters via contributions to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. For a complete list, please visit the Foundation website at: http://fnih.org/what-we-do/current-education-and-training-programs/mrsp

Footnotes

Contributors: SB: study conception, design, analysis and interpretation; critical review of study content; manuscript drafting; approval of the final manuscript. JL: study concept and interpretation; manuscript drafting; approval of the final manuscript. VH: study interpretation; manuscript drafting; approval of the final manuscript. CJM: study conception, design and interpretation; critical review of study content; manuscript drafting; approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and/or) its supplementary materials.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. . US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1308–16. 10.1093/cid/civ076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. . Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA 2014;312:1438. 10.1001/jama.2014.12923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010077. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morales DR, Slattery J, Pacurariu A, et al. . Relative and absolute risk of tendon rupture with fluoroquinolone and concomitant Fluoroquinolone/Corticosteroid therapy: population-based nested case-control study. Clin Drug Investig 2019;39:205–13. 10.1007/s40261-018-0729-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MCJM, Herings RMC, et al. . Increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture with quinolone antibacterial use, especially in elderly patients taking oral corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1801. 10.1001/archinte.163.15.1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise BL, Peloquin C, Choi H, et al. . Impact of age, sex, obesity, and steroid use on Quinolone-associated tendon disorders. Am J Med 2012;125:1228.e23–28. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sode J, Obel N, Hallas J, et al. . Use of fluroquinolone and risk of Achilles tendon rupture: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:499–503. 10.1007/s00228-007-0265-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyyssönen T, Lantto I, Lüthje P, et al. . Drug treatments associated with Achilles tendon rupture. A case-control study involving 1118 Achilles tendon ruptures. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2018;28:2625–9. 10.1111/sms.13281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WILTON L, PEARCE GL, MANN RD. A comparison of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, azithromycin and cefixime examined by observational cohort studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1996;41:277–84. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.03013.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jupiter DC, Fang X, Ashmore Z, et al. . The relative risk of Achilles tendon injury in patients taking quinolones. Pharmacotherapy 2018;38:878–87. 10.1002/phar.2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeger JD, West WA, Fife D, et al. . Achilles tendon rupture and its association with fluoroquinolone antibiotics and other potential risk factors in a managed care population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:784–92. 10.1002/pds.1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hori K, Yamakawa K, Yoshida N, et al. . Detection of fluoroquinolone-induced tendon disorders using a hospital database in Japan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:886–9. 10.1002/pds.3285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanne JH. FDA adds ‘black box’ warning label to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. BMJ 2008;337:a816. 10.1136/bmj.a816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food and Drug Administration FDA drug safety communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together. Available: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-advises-restricting-fluoroquinolone-antibiotic-use-certain [Accessed 12 Jun 2019].

- 15.Food and Drug Administration FDA drug safety communication: FDA updates warnings for oral and injectable fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to disabling side effects. Available: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-updates-warnings-oral-and-injectable-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics [Accessed 12 Jun 2019].

- 16.Del Buono A, Oliva F, Osti L, et al. . Metalloproteases and tendinopathy. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2013;3:51–7. 10.32098/mltj.01.2013.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai W-C, Hsu C-C, Chen CPC, et al. . Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011;29:67–73. 10.1002/jor.21196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corps AN, Harrall RL, Curry VA, et al. . Ciprofloxacin enhances the stimulation of matrix metalloproteinase 3 expression by interleukin-1beta in human tendon-derived cells. A potential mechanism of fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3034–40. 10.1002/art.10617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ResDAC Cms virtual research data center (VRDC). Available: https://www.resdac.org/cms-virtual-research-data-center-vrdc [Accessed 4 Oct 2019].

- 20.Cubanski J, Swoope C, Boccuti C, et al. . A primer on Medicare, 2015. Available: http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-a-primer-on-medicare-key-facts-about-the-medicare-program-and-the-people-it-covers [Accessed 7 Feb 2019].

- 21.Johnson ES, Bartman BA, Briesacher BA, et al. . The incident user design in comparative effectiveness research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:1–6. 10.1002/pds.3334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the Subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, et al. . Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:783–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med 2007;26:2389–430. 10.1002/sim.2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission MedPAC Data book: Beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid - January 2016, 2016. Available: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/publications/january-2016-medpac-and-macpac-data-book-beneficiaries-dually-eligible-for-medicare-and-medicaid.pdf?sfvrsn=0 [Accessed 23 Jan 2017].

- 26.The Chronic Condition Warehouse Chronic conditions data Warehouse: CCW chronic condition algorithms. Available: https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories [Accessed 23 Jan 2017].

- 27.Stricker BHC, Stijnen T. Analysis of individual drug use as a time-varying determinant of exposure in prospective population-based cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:245–51. 10.1007/s10654-010-9451-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shariff SZ, Cuerden MS, Jain AK, et al. . The secret of immortal time bias in epidemiologic studies. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:841–3. 10.1681/ASN.2007121354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shintani AK, Girard TD, Eden SK, et al. . Immortal time bias in critical care research: application of time-varying COX regression for observational cohort studies. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2939–45. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b7fbbb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin PC, Stuart EA. The performance of inverse probability of treatment weighting and full matching on the propensity score in the presence of model misspecification when estimating the effect of treatment on survival outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res 2017;26:1654–70. 10.1177/0962280215584401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zakaria MHB, Davis WA, Davis TME. Incidence and predictors of hospitalization for tendon rupture in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle diabetes study. Diabet Med 2014;31:425–30. 10.1111/dme.12344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basic-Jukic N, Juric I, Racki S, et al. . Spontaneous tendon ruptures in patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Blood Press Res 2009;32:32–6. 10.1159/000201792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jafari M, Ansari-Pour N. Why, when and how to adjust your P values? Cell J 2019;20:604–7. 10.22074/cellj.2019.5992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:1404–10. 10.1086/375078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White DW, Wenke JC, Mosely DS, et al. . Incidence of major tendon ruptures and anterior cruciate ligament tears in US army soldiers. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1308–14. 10.1177/0363546507301256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owens B, Mountcastle S, White D. Racial differences in tendon rupture incidence. Int J Sports Med 2007;28:617–20. 10.1055/s-2007-964837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corps AN, Harrall RL, Curry VA, et al. . Contrasting effects of fluoroquinolone antibiotics on the expression of the collagenases, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-1 and -13, in human tendon-derived cells. Rheumatology 2005;44:1514–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma C, Velpandian T, Baskar Singh S, et al. . Effect of fluoroquinolones on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase in debrided cornea of rats. Toxicol Mech Methods 2011;21:6–12. 10.3109/15376516.2010.529183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sbardella D, Tundo GR, Fasciglione GF, et al. . Role of metalloproteinases in tendon pathophysiology. Mini Rev Med Chem 2014;14:978–87. 10.2174/1389557514666141106132411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arabyat RM, Raisch DW, McKoy JM, et al. . Fluoroquinolone-associated tendon-rupture: a summary of reports in the food and drug administration’s adverse event reporting system. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015;14:1653–60. 10.1517/14740338.2015.1085968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, et al. . Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Med Sci 2013;10:796–803. 10.7150/ijms.6048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santavirta S, Takagi M, Konttinen YT, et al. . Inhibitory effect of cephalothin on matrix metalloproteinase activity around loose hip prostheses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996;40:244–6. 10.1128/AAC.40.1.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kannan R, Ruff M, Kochins JG, et al. . Purification of active matrix metalloproteinase catalytic domains and its use for screening of specific stromelysin-3 inhibitors. Protein Expr Purif 1999;16:76–83. 10.1006/prep.1999.1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Koning JS, Klazinga NS, Koudstaal PJ, et al. . The role of ‘confounding by indication’ in assessing the effect of quality of care on disease outcomes in general practice: results of a case-control study. BMC Health Serv Res 2005;5:10. 10.1186/1472-6963-5-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rolf CG, Fu S-C, Hopkins C, et al. . Presence of bacteria in spontaneous Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:2061–7. 10.1177/0363546517696315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tashjian RZ. Epidemiology, natural history, and indications for treatment of rotator cuff tears. Clin Sports Med 2012;31:589–604. 10.1016/j.csm.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen I. Rupture of the Achilles tendon; analysis of 57 cases. Acta Chir Scand 1953;106:50–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034844supp001.pdf (12.5MB, pdf)