Abstract

Mucoadhesive polymers are of significant interest to the pharmaceutical, medical device, and cosmetic industries. Polysaccharides possessing charged functional groups, such as chitosan, are known for mucoadhesive properties but suffer from poor chemical definition and solubility, while the chemical synthesis of polysaccharides is challenging with few reported examples of synthetic carbohydrate polymers with engineered-in ionic functionality. We report the design, synthesis, and evaluation of a synthetic, cationic, enantiopure carbohydrate polymer inspired by the structure of chitosan. These water-soluble, cytocompatible polymers are prepared via an anionic ring-opening polymerization of a bicyclic β-lactam sugar monomer. The synthetic method provides control over the site of amine functionalization and the length of the polymer while providing narrow dispersities. These well-defined polymers are mucoadhesive as documented in single molecule scale (AFM), bulk solution phase (FRAP), and ex vivo tissue experiments. Polymer length and functionality affects bioactivity as long, charged polymers display higher mucoadhesivity than long, neutral polymers or short, charged polymers.

Keywords: Biocompatibility, Carbohydrate Polymer, Cationic polymers, Mucoadhesive, Single Molecule Force Spectroscopy

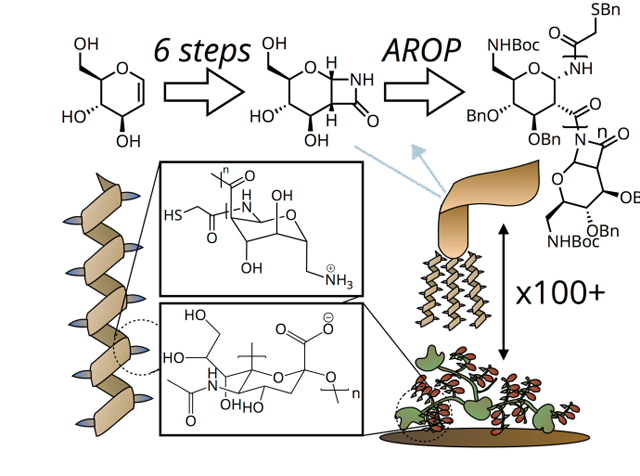

Graphical Abstract

We describe the synthesis of a novel Poly-Amido-Saccharide with regioselectively-introduced amine functionality, inspired by chitosan. These well-defined cationic polymers are biocompatible and nonimmunogenic. Single molecule force spectroscopy and ex vivo experiments reveal significant mucoadhesivity.

Mucus is a dense network comprised of macromolecular components including enzymes, extracellular nucleic acids, and high molecular weight proteins, including heavily glycosylated mucins[1]. Mucoadhesive materials, of interest for pharmaceutical, medical device, and cosmetic applications, adhere to this matrix through a combination of chain entanglement, ionic interactions, and hydrogen bonding[2–5]. Polysaccharides are uniquely suited to mucoadhesive applications due to their high degree of polymerization, rigid backbone structure, dense functionality with hydrogen bond-participating groups, and potential for ionic functionality. Chitosan, in particular, is a cationic naturally-obtained polysaccharide widely used as a mucoadhesive material[5–10] as it adheres through a combination of charge interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic effects[2]. Despite their advantages, well-defined polysaccharides for detailed experimental studies and for translational applications are difficult to obtain as they are mixtures of polymers of differing molecular weight and/or degree of branching, contaminated by chemically similar entities [11–13], and compositionally variable due to batch-to-batch variation as a result of being isolated from natural sources [14–17]. Alternatively, purely synthetic routes to such polymers are equally challenging as many of the desirable chemical characteristics of polysaccharides for biological applications (pyranose backbone, numerous hydroxyl functionalities, defined stereochemistry) necessitate rigorous and lengthy synthesis to prepare even oligosaccharides (<10 repeating units) [18–22]. Consequently, efforts are ongoing to develop carbohydrate-inspired polymers with non O-glycosidic linkages[23,24] such as amide[25], carbonate[26,27], and phosphodiester[28] linkages. These novel materials, however, fail to recapitulate all of the key physicochemical and biointerfacial properties of polysaccharides. Indeed, previously reported carbohydrate-inspired polymers largely suffer from poor aqueous solubility to complete insolubility, a lack of deprotected functional groups important for biological interaction (e.g., hydroxyls, amines, phosphates, carboxylates)[23,24,26–28], and/or rapid degradation in acidic or basic pH[23,24,29]. Moreover, the rigid pyranose ring backbone absent in some carbohydratemimic[25] and glyco-polymers[30] plays an essential role in polymer structure and resulting macroscale properties[31–33]. Thus, there is a significant unmet need for well-defined materials that closely resemble polysaccharides and possess their highly desirable properties, such as water solubility and deprotected functional groups, to harness in biomedical applications.

Herein, we describe a novel synthetic route and resulting carbohydrate polymer, inspired by the composition of chitosan, which shares many of its characteristics including a rigid pyranose backbone, hydroxyl functionalities, stereoregularity, and a regioselectively-introduced amine. The one-day polymerization of the protected sugar-β-lactam monomer yields polymers from 10 to 50 repeat units with low dispersity. In contrast to polysaccharides, these carbohydrate polymers, termed poly-amido-saccharides (PASs) [31,33–35] [36], possess an amide linkage between the carbohydrate repeat units. The polymers adhere to mucin with a length and charge dependency as demonstrated through a combination of molecular-based biophysical techniques as well as ex vivo analysis on mucosal tissue.

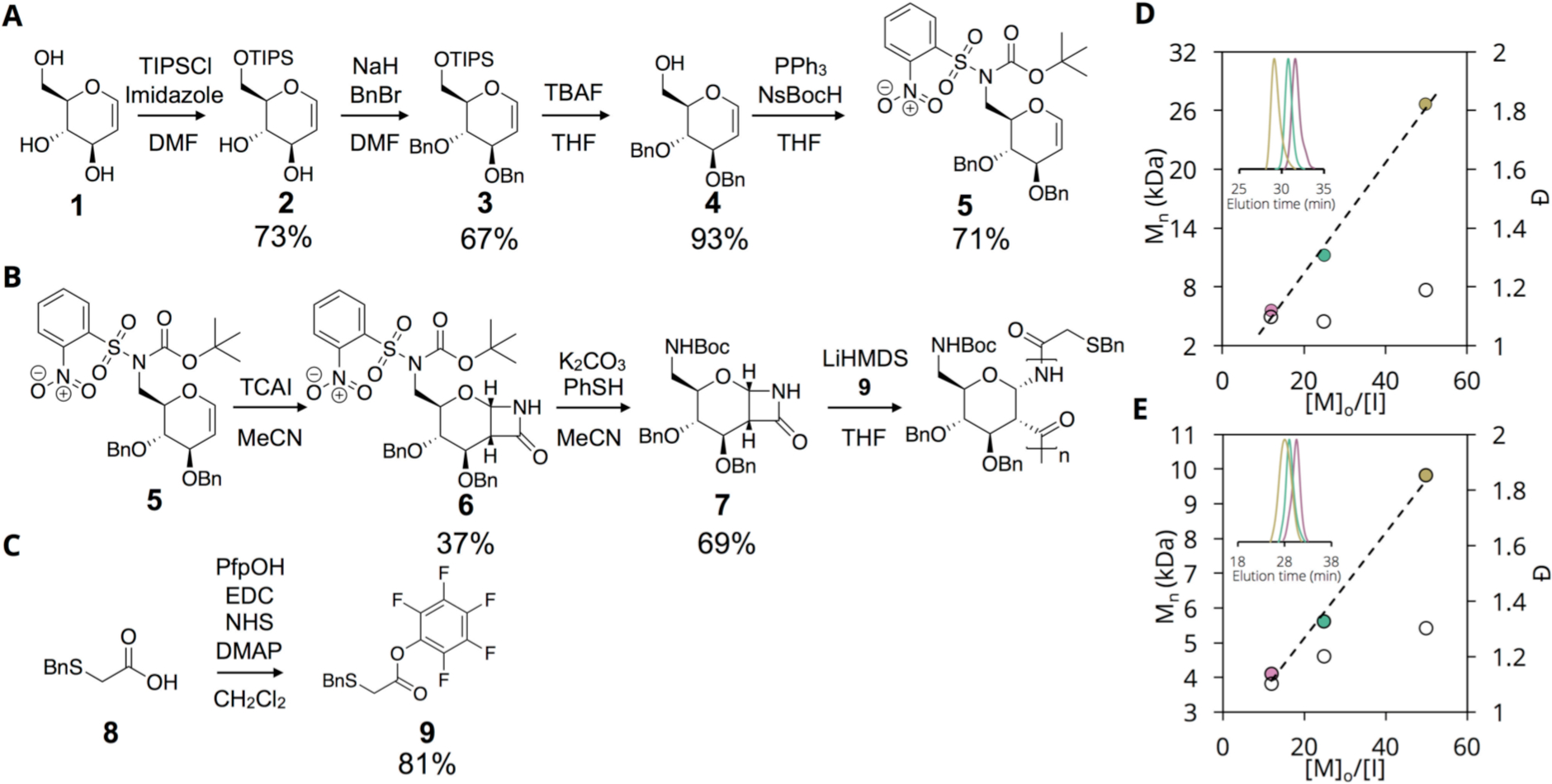

We are cognizant of the need to avoid the loss of chemical definition associated with post-polymerization modification as well as the need for facile, controlled and reproducible chemical synthesis of carbohydrate polymers, and, thus, we introduce an amine functionality at the monomer level followed by anionic ring-opening polymerization. As shown in Figure 1A, we first prepared a regioselectively amine-functionalized glycal from D-glucal (1) suitable for subsequent monomer synthesis and polymerization. Using the bulky triisopropylsilyl chloride group (TIPS-Cl), we regioselectively protected the primary 6’-OH in good yield (2), followed by introduction of O-benzyl groups at the 3’- and 4’-OH positions (3). With these positions protected, we subsequently removed the TIPS group with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to yield 4, thus regenerating the 6’-OH for functionalization. It should be noted that intermediate 4 serves as an important branching point for the synthesis of new regioselectively functionalized PAS monomers. Next, we converted the 6’-OH of 4 to a N-nosyl-N-boc protected 6’-N functionality using the Mitsunobu reaction with di-2-methoxyethyl azodicarboxylate (DMEAD) and triphenylphosphine (PPh3) (Figure 1B). The reaction of 5 with chlorosulfonyl isocyanate at −68 °C proceeded with significantly slower kinetics than previously observed with our benzyl-protected glycals (Figure S1). As an alternative strategy, we utilized the room temperature-stable trichloroacetyl isocyanate (TCAI), facilitating the 8–10 day cycloaddition reaction to form monomer 6. As we observed no polymer formation over 24 hours, we reduced the steric constraints of 6 by removing the N-nosyl group using K 2CO3 and PhSH to yield monomer 7, which polymerizes readily.

Figure 1.

Small molecule and polymer synthesis. (A) Synthesis of regioselectively-modified amine glycal; (B) Monomer synthesis, nosyl deprotection, and polymerization of amine-modified monomer; (C) Synthesis of thiol-containing initiator; (D) Mn vs [M]o/[I] for protected AmPAS (P1”-P3”); (E) Mn vs [M]o/[I] for deprotected AmPAS (P1-P3). Pink – P1, Green – P2, Gold – P3.

To obtain a single amine-orthogonal thiol functionality for post-polymerization conjugation to a fluorescent dye, we prepared the pentafluorophenyl ester of S-benzyl-thioglycolic acid (9) via a carbodiimide coupling reaction (Figure 1C). Using this Pfp ester 9, we synthesized the polymers in good yield (Figure 1B; Table 1), and the polymers exhibit molecular weights ranging from 5.6 to 26.6 kDa as [M]o/[I] is varied from 12 to 50 with dispersity <1.2 as determined by THF size exclusion chromatography with polystyrene standards (Figure 1D, GPC traces in S9A). The relatively straightforward synthetic methodology of PAS is especially attractive for the synthesis of amine-functional carbohydrate polymers, where there are relatively few literature examples and many of these suffer from low degrees of polymerization, poor aqueous solubility, and harsh reaction conditions[18].

Table 1.

Size exclusion chromatography of AmPAS polymers.

| Polymer | [M]o/[I] | Mn,theor (kDa) |

Mn,GPC (kDa) |

Mw,GPC (kDa) |

Ð | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P”1 | 12 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 1.2 | 72% |

| P”2 | 25 | 11.7 | 11.2 | 12.1 | 1.1 | 81% |

| P”3 | 50 | 23.4 | 26.6 | 29.2 | 1.1 | 79% |

| P1 | 12 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 41% |

| P2 | 25 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 79% |

| P3 | 50 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 13.2 | 1.3 | 73% |

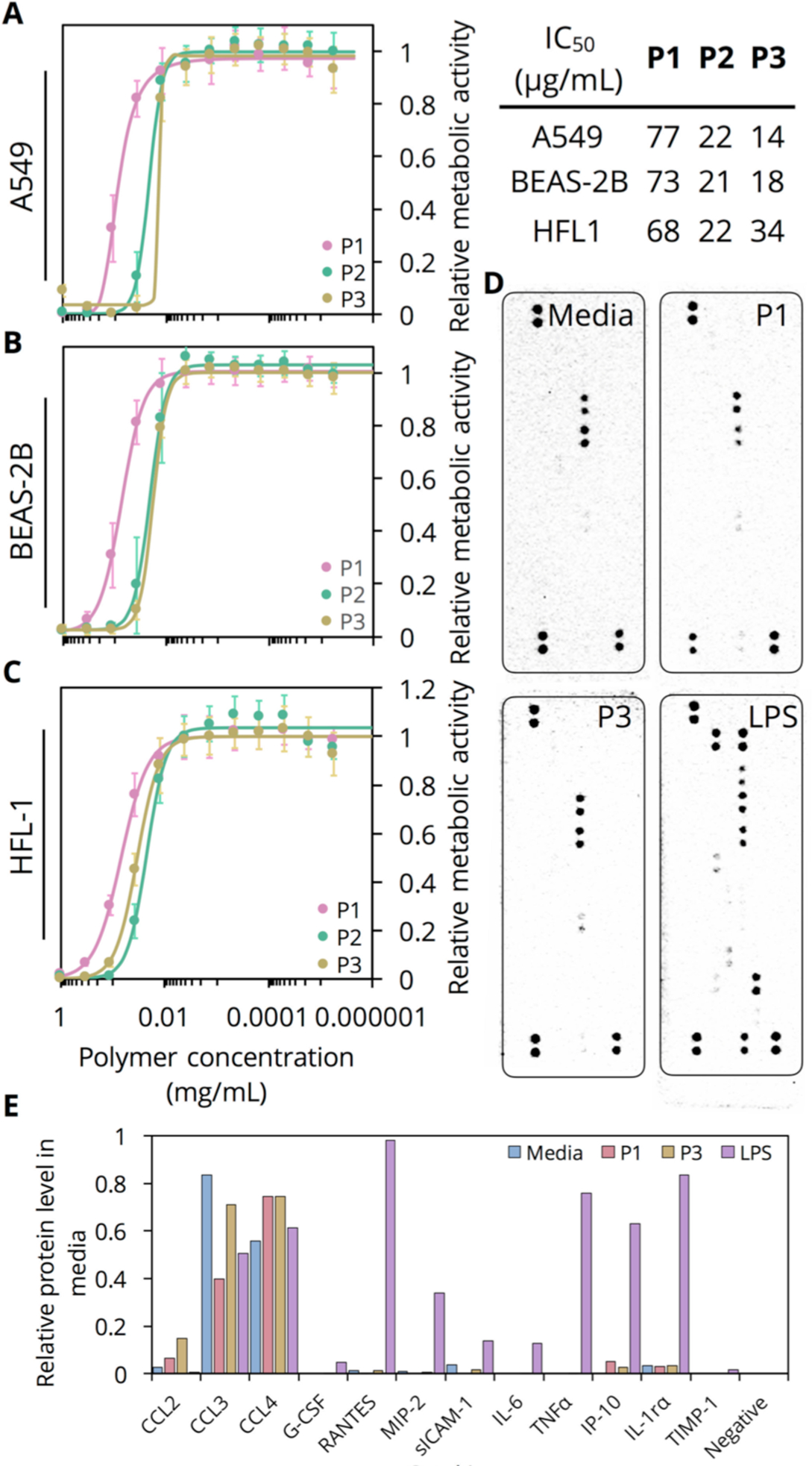

The NMR spectra of P1”-P3” confirm polymerization with the presence of broad peaks (Figure S2) and IR spectra show the amide bonds (~3200 cm−1 and ~1800 cm−1) and aromatic groups (~1100 cm−1) present on the polymer (Figure S3). To deprotect these polymers, as shown in Scheme 1, we removed the Boc group using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) followed by a Birch type reduction to remove the O- and S-benzyl groups (revealing the terminal thiol). The resulting water-soluble polymers were purified by dialysis against pure water and lyophilized to obtain white, cotton-like solids. All polymers possess molecular weights in good agreement with theoretical values and low dispersity <1.3 (NMR, IR, and GPC traces in S4–6, S8, S9B). IR spectra reveal a broad peak at 3300 cm−1 indicating deprotection of O-benzyl groups (Figure S4) and CD spectra display a minimum at 220 nm ([θ]MRE ~ −7 × 103 deg*cm2*dmol−1) and maximum at 180 nm ([θ]MRE ~ 30 × 103 deg*cm2*dmol−1) (Figure S5) consistent with a helical structure.

Scheme 1.

Deprotection of P1”-P3”.

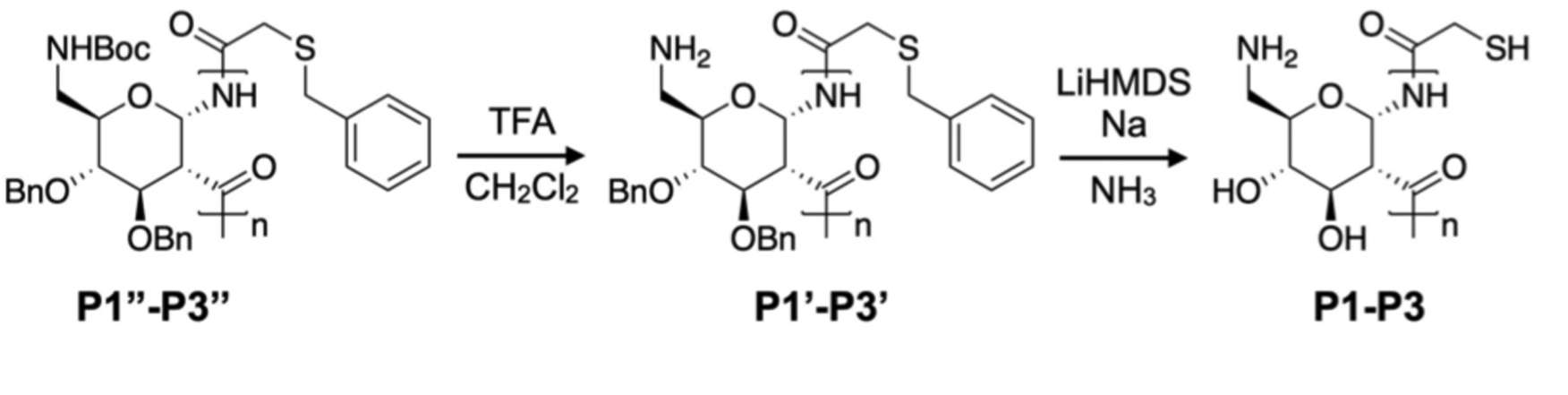

As a first step toward assessing the biocompatibility of P1-P3, we performed in vitro MTS proliferation assays with a set of respiratory tract cell lines. Following 24 hours of exposure to P1–P3, we observe <20% inhibition of proliferation for all cell lines at concentrations as high as 10 μg/mL (Figure 2A–C). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect on cell proliferation is length-dependent, with IC50 values for P1 across all cell lines between 68 and 77 μg/mL while the longer polymers P2 and P3 display IC50 values between 14 and 34 μg/mL. While exhibiting greater cytotoxicity than biocompatible PEG and Chitosan (both neutral at physiological pH), P3 exhibits >4 fold higher tolerability than the biocompatible[37] and similarly cationic linear PEI (MW 10 kDa, IC50 3.8 μg/mL) (Figure S11). Next, we performed multiplexed cytokine assays on RAW 264.7 cells[38] (see SI methods for detailed explanation of chemiluminescence assay) with P1 and P3, at a non-cytotoxic concentration of 10 μg/mL, to assess their potential to elicit an immune response. Following a 24-hour incubation period, the supernatant of wells exposed to P1 and P3 as well as those exposed to media alone (negative control) display nearly identical chemokine secretion profile (Figure 2D, 2E). In contrast, wells exposed to LPS (positive control) additionally show upregulation and secretion of the cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α[39]. In particular, the lack of IL-6 and TNF-α expression in RAW 264.7 cells incubated with P1 and P3 is highly encouraging and indicates that no component of P1 or P3 activates pattern recognition receptors on these cells.

Figure 2.

(A-C) MTS cell proliferation assay conducted on A549, BEAS-2B, and HLF-1 cells, respectively, exposed to P1-P3 for 24 hours (n=18, biological replicates). Hill functions fit to each curve to extract IC50 shown below corresponding graph. (D) Chemiluminescence images obtained (all 90 s exposure) for array panel membranes incubated with media of RAW 264.7 cells exposed to either media alone (negative control), P1, P3, or LPS (positive control). (E) Densitometric quantification of chemiluminescence signal.

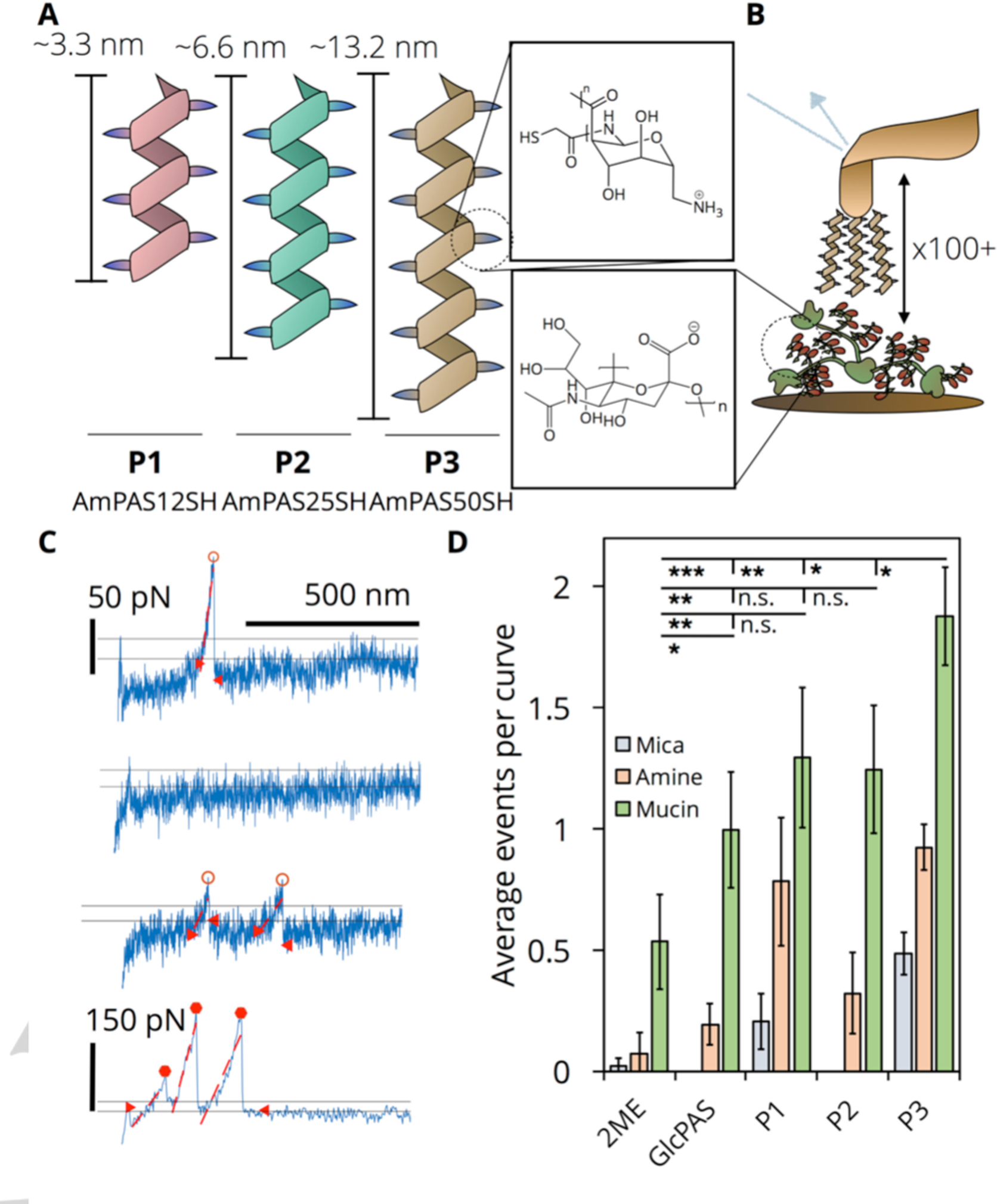

We hypothesize that polymers P1-P3 (Table 1), like other ionic carbohydrate polymers, will adhere to mucus as a result of their cationic charge, hydrogen bonding capability, and potential for chain entanglement with sialylated mucins. We selected single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS), which utilizes the optically-determined deflection of an AFM cantilever with known spring constant in order to calculate the force experienced by a probe conjugated to the tip during a molecular interaction event. This technique is ideal for biopolymer analyses as it is nondestructive, may be performed in solution, and can measure transient electrostatic or hydrogen-bonding interactions with samples of heterogenous molecular weight that would otherwise be lost in population averaged assays such as fluorescence polarization[40,41]. Thus, SMFS allows for the direct quantification of adhesive forces between molecules covalently attached to AFM tips and species covalently attached to smooth surfaces (e.g., silanized mica). For further background, we direct the reader to two reviews (Newman, 2008[40] and Hughes, 2016[41]) on the SMFS technique. We conjugated P1-P3, 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME), and a thiol-terminated 50-mer neutral PAS (GlcPAS50) to gold-coated AFM tips via thiol-gold chemistry (Figure 3B) and performed repeated extension and retractions from a porcine gastric mucin (PGM) coated mica surface in 10 mM PBS buffer pH 7.4 (Figure S12). Hysteresis between the extension and retraction curves corresponds to adhesion events, which reflect intermolecular interactions at rupture lengths greater than 20 nm[42] (Figure 3C). When comparing between tips on mucin-functionalized surfaces, all four polymer functionalized tips exhibit significantly higher adhesion event probability than 2ME functionalized tips (0.5 average events per curve) as expected (Figure 3D). Additionally, P3 displays a significantly higher adhesion event probability on mucin-coated surfaces (1.88 average events per curve) than all other tips due to its combination of positive charge and relatively higher chain length. The observation of no statistically significant difference between P1 and P2, which are short, positively-charged polymers, and the longer, uncharged GlcPAS50 support the hypothesis that the increased likelihood of interaction for P3 is a result of the combination of these two independently acting factors.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic of polymers P1-P3 and their estimated average lengths[31]; AmPAS12SH – P1, AmPAS25SH – P2, AmPAS50SH – P3. Magnified: structure of repeating polymer subunit. (B) Schematic of SMFS experiment. Magnified: structure of sialic acid. (C) Representative retraction curves obtained from SMFS. D. Average number of adhesion events per curve comparing 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME), GlcPAS, DP 50, and P1-P3 tips over: unmodified mica (negative control), amine silanized (negative control), and mucin functionalized. Data obtained by randomly selecting 5 sets of 20 curves to tabulate average number of events. This was repeated three times to generate an average and standard deviation (error bars) (n.s., p> 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001).

Adhesion events at the single molecule scale are stochastic, occurring with varying rupture lengths, rupture forces, and adhesion energies (area under curve)[43]. Analyzing the statistical distribution of these three parameters, computationally extracted from all recorded retraction curves, allows for the detailed characterization of the nature of adhesion events and discrimination between weaker and stronger events. Due to the heterogeneity of polymer-mucin interactions, histograms of each parameter were fit to mixed model Gaussians that are a weighted linear combination of 2 independent Gaussians each with its own mean and standard deviation (Table S14). As shown in Figure 4A, this statistical analysis quantifies the observed elongation of GlcPAS50 and P3 rupture length histograms, each with a significant number of counts above 200 nm, in comparison to 2ME. While the mixed model Gaussian distribution of 2ME is described by a single mean of 87 nm, the distributions of GlcPAS50 and P3 include contributions with 35% and 47% weight from means of 340 and 390 nm, respectively. The modeled rupture length distributions of P1 and P2 similarly include significant weight (>28%) from means greater than 200 nm (Figure S15). In contrast, the rupture force distributions (Figure 4B) for all tips exhibit minimal differences with all possessing mixed model Gaussian means of 60 and 230 pN; total counts, however, are higher for P3 versus 2ME.

Figure 4.

Left, 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME); middle – GlcPAS50; right – P3 (AmPAS50). Mixed model Gaussian fits were applied to generate probability distribution functions and the integral was scaled to match the histogram area. (A-C) Histograms of computationally extracted rupture length, rupture force, and adhesion energy, respectively. (D) Scatter plots of maximum rupture force (pN) vs rupture length (nm) for all adhesion events on mucin-functionalized surfaces. Point area is scaled by the adhesion energy of that event (smaller circle – less adhesion energy).

Despite comparable rupture forces, the observed force-deflection curves (e.g., Figure 3C) of 2ME are generally sharp, narrow peaks unlike the broad and exponentially increasing peaks of P3. These differences manifest in the adhesion energy (Figure 4C) histograms and mixed model Gaussians for each functionalized tip. While the 2ME adhesion energy histogram is modeled by a single distribution with a mean of 0.83 aJ, the modeled distribution for P3 is described by significantly larger means of 2.2 and 33 aJ (68% and 32% weight, respectively). Mixed model Gaussians of P1 and P2 similarly include a significant (>23%) contribution from a 22 aJ mean (Figure S16). Importantly, the adhesion energy mixed model means for P1-P3 are all larger than those calculated for GlcPAS50 (0.9 and 13 aJ). Finally, as evident in scatter plots combining all 3 parameters (Figure 4D), P3 exhibits higher event frequency, rupture length, and adhesion energy in comparison to 2ME and GlcPAS50. This is particularly apparent at rupture lengths above 200 nm where P3 rupture force distributions include weight from a mean of 200 pN (Figure S17) while those of GlcPAS50 are below 80 pN. This observed mean rupture force of ~200 pN agrees with previously reported values for Chitosan and PGM at an identical tip retraction speed of 1 μm/s[42]. Taken together, these data show that while P1-P3 and GlcPAS50 are all capable of binding with mucin, P3 possesses a unique combination of positive charge and chain length that translates to significant mucoadhesivity.

Next, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments on TAMRA-labeled P3 and FITC-labeled dextran in water and in dilute (0.5 mg/mL) and concentrated (10 mg/mL) mucin solutions. We additionally examined low molecular weight FITC-labeled alginate and chitosan, to compare P3 to other charged, mucoadhesive polymers. In a 20 mM HEPES solution, the TAMRA-labeled P3 diffuses slower than FITC-dextran with a diffusion coefficient of 1.7 × 10−7 versus 1.3 × 10−6 cm2/s. Moreover, when dissolved in a 10 mg/mL mucin solution, the diffusion coefficient of TAMRA-labeled P3 decreases by nearly 70% to 5.3 × 10−8 cm2/s (Figure S18A) while remaining relatively unchanged for the uncharged and non-mucoadhesive FITC-dextran (Figure S18B). FITC-alginate exhibits a similar 80% reduction in diffusion coefficient with increasing mucin concentration, while only a modest 50% drop is observed for FITC-chitosan (Figure S18C–D).

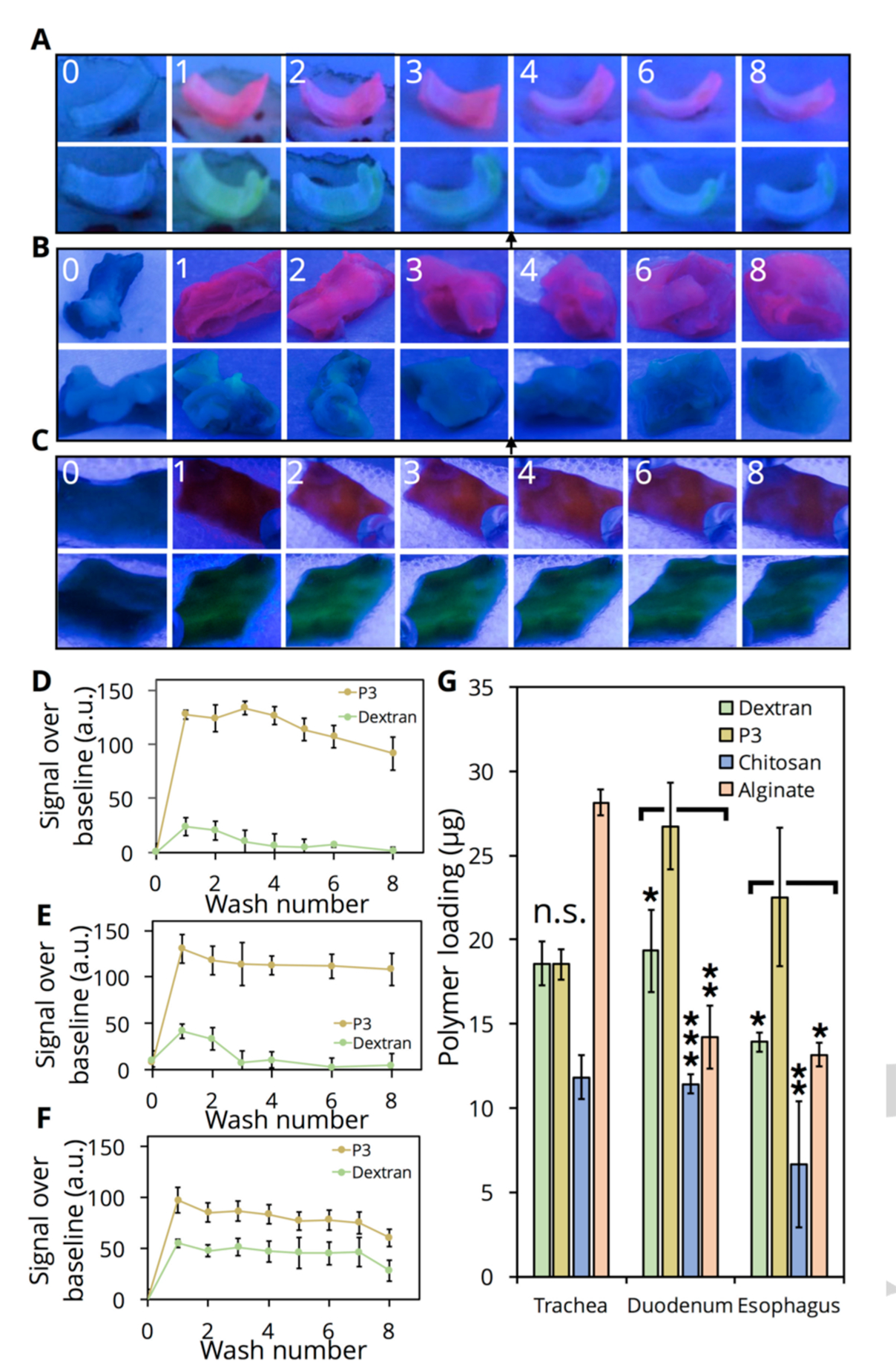

While the single molecule and bulk measurements presented hitherto provide insight into the mechanism and factors associated with interactions between P1-P3 and mucin, their effectiveness in mucoadhesive nanoformulations is best characterized by their adhesion to animal tissue. Thus, we incubated samples of trachea (porcine, Figure 5A), esophagus (ovine, Figure 5B), and duodenum (porcine, Figure 5C), each possessing either a significant number of mucus-producing goblet cells on their inner lumen or glandular mucus secretion, in PBS solutions of either TAMRA-labeled P3 or FITC-dextran for 30 min and then subjected the samples to repeated washing with PBS to remove the bound polymer. The average fluorescence intensity measured on each tissue sample increases after incubation with both FITC-dextran and TAMRA-P3 (Figure 5A, B). Samples incubated with TAMRA-P3, however, demonstrate a significantly higher increase in fluorescence intensity post-incubation compared to FITC-dextran. In the case of porcine trachea and ovine esophageal tissue (Figure 5A–D), FITC-dextran adheres slightly (40 units above baseline) and this signal is readily lost upon washing the sample 3 times in PBS. In contrast, the TAMRA-P3 soaked tissue shows significant loading (120–130 units above baseline) and a large portion of this loading (>75%) remains after 7 washes. While the increase in signal relative to baseline is still higher for TAMRA-P3 on porcine duodenum tissue (Figure 5E–F), compared to FITC-dextran, both polymers remain with little loss of signal until wash 7. To quantify initial tissue loading of P3 in comparison to dextran and the mucoadhesive, charged chitosan and alginate, we incubated fresh porcine trachea, duodenum, and esophagus samples with fluorescently labeled polymers, followed by a quick PBS wash and vigorous sonication for 1 h to remove all bound polymer. We only observed high loading for alginate on trachea samples and poor loading for chitosan on all tissues, despite their known mucoadhesivity. Nevertheless, significantly higher loading of P3 occurs on duodenum and esophagus samples compared to dextran, chitosan, and alginate. These data support our hypothesis that TAMRA-P3 strongly adheres to biological tissue and resists clearance (i.e., enhanced residence time), in agreement with results obtained through AFM and FRAP experiments.

Figure 5.

(A-C) Images under UV irradiation (fixed illumination distance) of porcine trachea (A), ovine esophagus (B), and porcine duodenum (C) collected from a freshly sacrificed animal (0) and incubated with either TAMRA-P3 or FITC-dextran for 30 minutes (1) and washed up to 7 times afterwards (2–8). Images are of the same sample over each wash. (D-F) Quantification of images, split into RGB channels and followed by densitometry, obtained for each tissue sample (n=3). Values obtained relative to samples in PBS only to account for background. Error bars represent the variability in densitometry between independent tissue samples. (G) Tissue loading of FITC-dextran, FITC-alginate, FITC-chitosan, or TAMRA-P3. Tissue samples incubated with polymer for 30 minutes followed by vigorous sonication to remove bound polymer; fluorescence quantified via plate reader against standard curve (n=3 tissue samples). Error bars are standard deviation (n.s., p> 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001).

In summary, we report the synthesis of enantiopure cationic carbohydrate polymers via anionic ring-opening polymerization of a bicyclic β-lactam sugar monomer. Our synthetic method imparts regioselective amine functionalization and control over the length of the polymer with narrow dispersities. Results from single molecular force spectroscopy demonstrate that tuning polymer length impacts nanoscale interactions, as polymers with degree of polymerization of 50 (P3) interact with mucin with significantly higher frequency and adhesion energy than 2-mercaptoethanol, GlcPAS (degree of polymerization 50, noncationic control), P1 (degree of polymerization 12), and P2 (degree of polymerization 25). Additionally, in contrast to the non-mucoadhesive dextran, P3 adheres to ex vivo mucin coated tissues. Mucosal routes for drug delivery are underutilized in comparison to parenteral administration, in spite of the large available surface area and minimal invasiveness, due to the lack of well-defined polymeric materials available for tunable adhesion, prolonged retention time, and modification of viscosity. The highly controlled synthetic methodology and associated tunability in biointerfacial properties of these cytocompatible and bioinspired PASs expands the formulation scientist’s toolkit for mucosal drug delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by BU and DOD USU (HU0001810012). The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Anderson Chen of the BU BME Micro/Nano imaging facility, Dr. Clemens Anklin of Bruker BioSpin, and Dr. Paul Ralifo of the BU Chemical Instrumentation Center for assistance.

References

- [1].Rubin BK, Respir. Care 2002, 47, 761–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sogias IA, Williams AC, Khutoryanskiy VV, Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1837–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang YY, Lai SK, So C, Schneider C, Cone R, Hanes J, PLoS One 2011, 6, e21547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sosnik A, Das Neves J, Sarmento B, Prog. Polym. Sci 2014, 39, 2030–2075. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Smart JD, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2005, 57, 1556–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Valenta C, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2005, 57, 1692–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Takeuchi H, Yamamoto H, Kawashima Y, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2001, 47, 39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jayakumar R, Menon D, Manzoor K, V Nair S, Tamura H, Carbohydr. Polym 2010, 82, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- [9].George M, Abraham TE, Control J. Release 2006, 114, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Casettari L, Illum L, Control J. Release 2014, 190, 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tam SK, Dusseault J, Polizu S, Ménard M, Hallé J-P, Yahia L, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lieder R, Gaware VS, Thormodsson F, Einarsson JM, Ng C-H, Gislason J, Masson M, Petersen PH, Sigurjonsson OE, Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 4771–4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Paredes-Juarez GA, de Haan BJ, Faas MM, de Vos P, Mater. (Basel, Switzerland) 2014, 7, 2087–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sabrina B, Antonella B, Giangiacomo T, Donata B, Terbojevich M, Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen RH, Chang JR, Shyur JS, Carbohydr. Res 1997, 299, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kabat E, Bezer A, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1958, 78, 306–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Stefansson M, Anal. Chem 1999, 71, 2373–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xiao R, Grinstaff MW, Prog. Polym. Sci 2017, 74, 78–116. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Werz DB, Seeberger PH, Chem. - A Eur. J 2005, 11, 3194–3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Calin O, Eller S, Seeberger PH, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2013, 52, 5862–5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stallforth P, Lepenies B, Adibekian A, Seeberger PH, J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 5561–5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seeberger PH, Werz DB, Nature 2007, 446, 1046–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Li L, Knickelbein K, Zhang L, Wang J, Obrinske M, Ma GZ, Zhang L-M, Bitterman L, Du W, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 13078–13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li L, Wang J, Obrinske M, Milligan I, O’Hara K, Bitterman L, Du W, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 6972–6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Metzke M, O’Connor N, Maiti S, Nelson E, Guan Z, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2005, 44, 6529–6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gustafson TP, Lonnecker AT, Heo GS, Zhang S, Dove AP, Wooley KL, Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3346–3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lonnecker AT, Lim YH, Wooley KL, ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 748–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tsao Y-YT, Wooley KL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 5467–5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Felder SE, Redding MJ, Noel A, Grayson SM, Wooley KL, Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ladmiral V, Melia E, Haddleton DM, Eur. Polym. J 2004, 40, 431–449. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chin SL, Lu Q, Dane EL, Dominguez L, McKnight CJ, Straub JE, Grinstaff MW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6532–6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dane EL, Chin SL, Grinstaff MW, ACS Macro Lett. 2013, 2, 887–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xiao R, Dane EL, Zeng J, McKnight CJ, Grinstaff MW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 14217–14223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dane EL, Grinstaff MW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 16255–16264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Stidham SE, Chin SL, Dane EL, Grinstaff MW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 9544–9547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dane EL, Chin SL, Grinstaff MW, ACS Macro Lett. 2013, 2, 887–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Perevyazko IY, Bauer M, Pavlov GM, Hoeppener S, Schubert S, Fischer D, Schubert US, Langmuir 2012, 28, 16167–16176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Derive M, Bouazza Y, Alauzet C, Gibot S, Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1040–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Liu Y, Yin H, Zhao M, Lu Q, Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol 2014, 47, 136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Neuman KC, Nagy A, Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 491–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hughes ML, Dougan L, Reports Prog. Phys 2016, 79, 076601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Haugstad KE, Håti AG, Nordgård CT, Adl PS, Maurstad G, Sletmoen M, Draget KI, Dias RS, Stokke BT, Polymers (Basel). 2015, 7, 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Janshoff A, Neitzert M, Oberdörfer Y, Fuchs H, Angew. Chemie 2000, 39, 3212–3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.