Highlights

-

•

Complications and death are considerable among hospitalized patients with typhoid fever.

-

•

Case fatality ratio of typhoid fever was higher in Africa compared to Asia.

-

•

Among studies in Africa, 20% of patients with typhoid intestinal perforation died.

-

•

Delays in care were correlated with increased typhoid case fatality ratio in Asia.

Keywords: Typhoid fever, Case fatality ratio, Meta-analysis, Mortality, Intestinal perforation

Summary

Objectives

Updated estimates of the prevalence of complications and case fatality ratio (CFR) among typhoid fever patients are needed to understand disease burden.

Methods

Articles published in PubMed and Web of Science from 1 January 1980 through 29 January 2020 were systematically reviewed for hospital or community-based non-surgical studies that used cultures of normally sterile sites, and hospital surgical studies of typhoid intestinal perforation (TIP) with intra- or post-operative findings suggestive of typhoid. Prevalence of 21 pre-selected recognized complications of typhoid fever, crude and median (interquartile range) CFR, and pooled CFR estimates using a random effects meta-analysis were calculated.

Results

Of 113 study sites, 106 (93.8%) were located in Asia and Africa, and 84 (74.3%) were non-surgical. Among non-surgical studies, 70 (83.3%) were hospital-based. Of 10,355 confirmed typhoid patients, 2,719 (26.3%) had complications. The pooled CFR estimate among non-surgical patients was 0.9% for the Asia region and 5.4% for the Africa region. Delay in care was significantly correlated with increased CFR in Asia (r = 0.84; p<0.01). Among surgical studies, the median CFR of TIP was 15.5% (6.7–24.1%) per study.

Conclusions

Our findings identify considerable typhoid-associated illness and death that could be averted with prevention measures, including typhoid conjugate vaccine introduction.

Introduction

Typhoid fever is caused by the organism Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi (Salmonella Typhi); a systematic infection transmitted predominantly through water or food contaminated by human feces.1, 2, 3 Typhoid fever presents clinically across a spectrum of severity with a range of symptoms and signs including fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, that make differentiating it from other febrile and gastrointestinal illnesses challenging.2 The ‘gold standard’ diagnostic method for typhoid fever is the culture of blood, bone marrow, or another normally sterile site. However, clinical microbiology services are not widely available in endemic areas and culture-based diagnosis has incomplete sensitivity.4 Additionally, delays in diagnosis and treatment occur as a result of barriers to care, such as difficulty accessing tertiary facilities because of delayed referral, distance, and the cost of healthcare.5, 6, 7

Timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of typhoid fever in the community is needed to avert complications requiring hospitalization, and death.2 Typhoid complications include typhoid intestinal perforation (TIP), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hepatitis, cholecystitis, myocarditis, shock, encephalopathy, pneumonia, and anemia.1,2 TIP and gastrointestinal hemorrhage are serious complications that are often fatal, even if managed surgically.8,9

Prevention of typhoid fever by improved sanitation and increased access to clean, safe water and food remains critical,10, 11, 12 but requires substantial investment over long time scales. Typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) has been pre-qualified and recommended by the World Health Organization for routine use13 and represents a tool to prevent typhoid illness and deaths in a short time horizon, complementing progress in sanitation, water, and food safety improvements.14 In typhoid-endemic countries, TCV pre-qualification allows for priority access and funding, removing important hurdles for vaccine introduction into routine immunization schedules.15

While previous systematic reviews have examined the case fatality ratio (CFR) of typhoid fever, they did not capture the substantial number of observational studies on typhoid fever published in recent years. Furthermore, some past reviews were restricted by location, population, or age.10,16, 17, 18, 19 In order to support country-level decisions on typhoid control, including TCV introduction, and to provide contemporary estimates of morbidity and mortality, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of complications and case fatality ratio (CFR) among patients with typhoid fever.

Methods

Search strategy

We systematically reviewed PubMed and Web of Science for published articles on the complications and mortality of typhoid fever. Each database was searched for key words of Salmonella Typhi, mortality, case fatality, died, death, complications, perforation, and hemorrhage (Supplementary Appendix A). Since a previous review reported on the mortality of typhoid fever prior to 1980,20 our search was limited to articles published from 1 January 1980 through 29 January 2020. We placed no restrictions on language, country, or demographics. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Supplementary Appendix B)21 and the protocol was registered with PROPSERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on 10 July 2020 (CRD42020166998). Ours was a study of published data and as such, institutional review board approval was not required.

Study selection

We selected ‘non-surgical studies’ reporting the proportion of participants with Salmonella Typhi infection who had typhoid-associated complications or who died. In such studies, Salmonella Typhi infection was required to be ascertained by culture of a normally sterile site (e.g., blood). We also selected ‘surgical studies’ of only participants undergoing surgery for intestinal perforation. Surgical studies were included if gross intraoperative findings contained the keywords ‘terminal ileum,’ ‘antimesenteric perforation,’ or ‘confirmed at laparotomy’ to assign perforations as TIP.8,9 We also accepted postoperative criteria including the use of histopathology stains or immunohistochemistry to differentiate alternative causes for perforation (e.g., tuberculosis) and to attribute the cause of perforation to Salmonella Typhi. Consequently, we considered participants from non-surgical studies as having ‘confirmed,’ and those from surgical studies as having ‘probable,’ typhoid fever. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for search strategy of complications and mortality of typhoid fever systematic review.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

Titles and abstracts were downloaded from each database, imported into Endnote X8 (Clarivate Analytics, Boston, MA, USA), and combined into one reference list. Duplicates were removed by Endnote, and the de-duplicated list of articles was uploaded to the online systematic review tool Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar) for screening.22 Each subsequent process, including title and abstract review, full text review, and data abstraction, was performed in parallel by two authors (CSM and MB). A third author (JAC) was consulted when CSM and MB were unable to resolve discrepancies through discussion. The full text of 33 studies included in a systematic review on typhoid incidence were additionally screened.23 Data were then abstracted into a shared Google Sheets spreadsheet (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Data abstraction

Abstracted study characteristics included the first author, publication year, article identifier (e.g., PubMed ID), year data collection started and ended, the city, district, or locality of the study, region and sub-region as classified by the United Nations (UN),24 type of normally sterile site cultured or study-specific TIP definition, whether participants were recruited from the community or a hospital, and if the study was non-surgical or surgical.

Data were abstracted for the mean and median fever, illness, or symptom duration prior to presentation; inclusion age and age range of participants; total number of confirmed or probable typhoid cases; number and type of complications; and number of deaths attributed to typhoid fever. When reported, we abstracted CFR data for MDR cases, defined by authors as infection with Salmonella Typhi resistant to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and non-MDR cases, defined by authors as susceptible to at least one of the first-line antimicrobials. We also noted the proportion of male and female participants with TIP.

Data on duration of fever, duration of illness, and duration of symptoms prior to treatment were used as a proxy for delays in accessing care and subsequently combined as one metric of ‘delay in care.’ We categorized the ages of participants into three groups based on inclusion age and age range: ‘children’ were ≤15 years old, ‘adults’ >15 years, and ‘mixed ages’ were studies of both children and adult participants. Complications were classified two ways. First, we used a pre-selected list of 21 complications defined by Parry and colleagues.1 If a study mentioned any complication from the list, regardless of whether the study defined it as a typhoid complication, we abstracted the data. Second, we noted separately when a study specifically used the term ‘complication’ associated with typhoid fever. We did not abstract complications following surgery nor those attributed to the surgical procedure. If a study described an initial diagnosis, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and other syndromes that overlapped with complications of typhoid fever from our pre-selected list, it was not recorded as a complication due to lack of attribution to typhoid by the authors of the study. The final dataset was reviewed by a third author (JAC) for completeness and accuracy.

Data analysis

For each non-surgical study, we divided the number of each pre-selected complication by the number of confirmed typhoid cases to calculate the prevalence of the specific complication. We divided the number of deaths attributed to typhoid fever by the total number of confirmed typhoid cases to calculate a CFR. We calculated the median and interquartile (IQR) range CFR for studies across each UN region and a pooled CFR estimate using a random effects model meta-analysis with MetaXL (Epigear International version 5.3). For pooled CFR estimates, we also stratified by UN sub-region and by age group. Among surgical studies of TIP, we calculated the CFR of TIP among probable typhoid cases and the prevalence of TIP among male and female participants.

Proportions were compared by Χ2 test, means by t-test, and the relationship between delay in care and CFR by Pearson's correlation coefficient (r), in R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and considered significant if p <0.05. We assessed bias throughout the analyses by separating non-surgical and surgical analyses, by stratifying by region, sub-region, age, and study recruitment setting, and by heterogeneity using I2.

Results

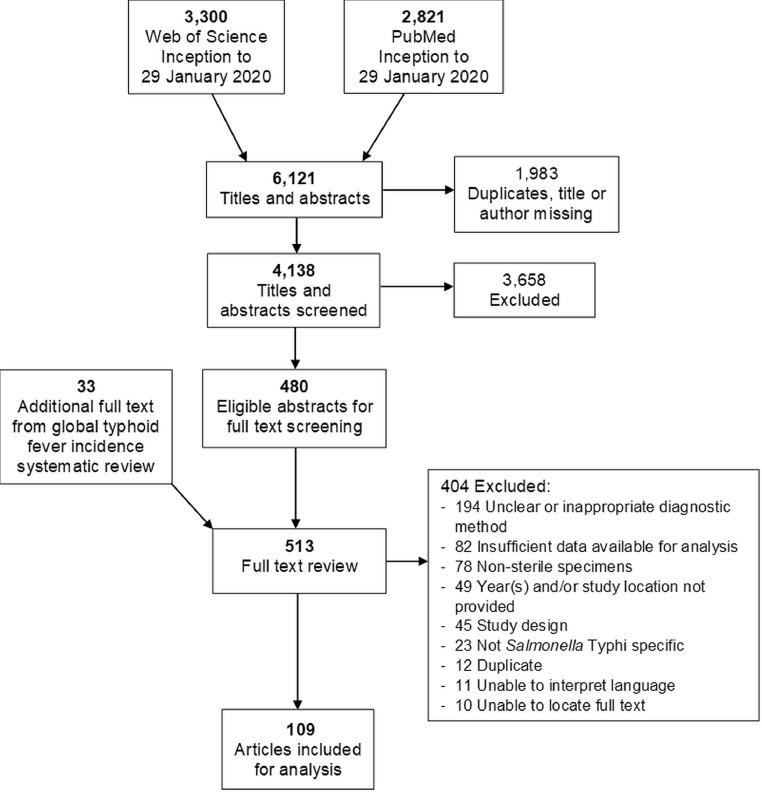

Our search strategy returned 6,121 articles (Fig. 1). Of 513 full text articles reviewed, 404 were excluded. An unclear or inappropriate diagnostic method due to inadequate description of how a confirmed or probable typhoid case was defined was the most common reason for exclusion. We were unable to translate the language of 11 articles and we were unable to locate the full text of 10 articles. A total of 109 articles were included for analysis.20,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of search strategy and selection of articles for mortality and complications of typhoid fever, 1965–2018.

Study characteristics

Among the 109 articles, one (0.9%) collected data in five countries,90 resulting in 113 study sites (Supplementary Appendix C). Among 113 study sites, data were collected from 1965 through 2018 and from every UN region; 62 (54.9%) in Asia, 44 (38.9%) in Africa, four (3.5%) in the Americas, two (1.8%) in Oceania, and one (0.9%) in Europe. Eighty-four (74.3%) sites recruited non-surgical typhoid fever participants and 29 (25.7%) were surgical studies of TIP. Among 84 non-surgical studies, 70 (83.3%) were hospital-based and 14 (16.7%) were community-based. There were 14,007 confirmed cases of typhoid fever with a median (IQR) of 64 (25–190) cases per study; 12,889 (92.0%) were from hospital-based and 1,118 (8.0%) from community-based studies. Among 29 surgical study sites, there were 2,926 probable cases of typhoid with a median of 58 (46–104) cases per study. Of the 16,933 total confirmed or probable cases, 11,973 (70.7%) were from Asia, 3,642 (21.5%) from Africa, 739 (4.4%) from Oceania, 554 (3.3%) from the Americas, and 25 (0.1%) from Europe. Sixty-seven (59.3%) of 113 study sites recruited participants of a mixed age, 35 (31.0%) recruited only children, and 11 (9.7%) only adults.

Typhoid fever complications

Of the 84 non-surgical study sites, 56 (66.7%) reported at least one complication occurring from the list of pre-selected complications. Among 10,335 cases of confirmed typhoid fever, there were 2,719 (26.3%) complication events (Table 2). Delirium and anemia were the most prevalent complications, occurring in 705 (26.6%) of 2,648 and 1,017 (21.4%) of 4,756 confirmed cases, respectively. Eighty (1.3%) of 6,064 participants had TIP; 34 (0.7%) of 4,622 participants in Asia and 37 (7.6%) of 486 participants in Africa. Twenty-seven (32.1%) of 84 sites described unspecified complications for 669 (15.1%) of 4,442 confirmed cases. Asymptomatic electrocardiographic changes, impairment of coordination, pharyngitis, and chronic carriage were not reported from any of the included non-surgical study sites. Data on miscarriage were available in one study of pregnant women,42 occurring in one (16.7%) of six with confirmed typhoid fever. Although not in the Parry et al. list of typhoid complications, seizures or convulsions were reported among 108 (2.5%) of 4,349 typhoid patients.

Table 2.

Complications of typhoid fever, by United Nations region, 1965–2018.

| Complicationsa |

Africa |

Americas |

Asia |

Oceania |

Totalb |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n / | N | (%) | n / | N | (%) | n / | N | (%) | n / | N | (%) | n / | N | (%) | |

| Abdominal | |||||||||||||||

| Intestinal perforation | 37 / | 486 | (7.6) | 4 / | 217 | (1.8) | 34 / | 4,622 | (0.7) | 5 / | 739 | (0.7) | 80 / | 6,064 | (1.3) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 11 / | 320 | (3.4) | 0 / | 0 | — | 87 / | 2,809 | (3.1) | 21 / | 739 | (2.8) | 119 / | 3,868 | (3.1) |

| Hepatitis | 10 / | 157 | (6.4) | 1 / | 9 | (11.1) | 104 / | 2,389 | (4.4) | 17 / | 739 | (2.3) | 132 / | 3,294 | (4.0) |

| Cholecystitis | 1 / | 55 | (1.8) | 0 / | 0 | — | 10 / | 913 | (1.1) | 0 / | 365 | (0.0) | 11 / | 1,333 | (0.8) |

| Cardiovascular | |||||||||||||||

| Asymptomatic electrocardiographic changes | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||||

| Myocarditis | 2 / | 191 | (1.0) | 0 / | 0 | — | 30 / | 1,979 | (1.5) | 1 / | 365 | (0.3) | 33 / | 2,535 | (1.3) |

| Shock | 0 / | 14 | (0.0) | 0 / | 0 | — | 59 / | 3,580 | (1.6) | 17 / | 365 | (4.7) | 76 / | 3,959 | (1.9) |

| Neuropsychiatric | |||||||||||||||

| Encephalopathy | 0 / | 0 | — | 0 / | 0 | — | 98 / | 2,460 | (4.0) | 4 / | 365 | (1.1) | 102 / | 2,825 | (3.6) |

| Delirium | 34 / | 277 | (12.3) | 0 / | 0 | — | 650 / | 2,027 | (32.1) | 21 / | 344 | (5.8) | 705 / | 2,648 | (26.6) |

| Psychotic states | 2 / | 50 | (4.0) | 2 / | 217 | (0.9) | 28 / | 1,438 | (1.9) | 0 / | 0 | — | 32 / | 1,705 | (1.9) |

| Meningitis | 6 / | 347 | (1.7) | 1 / | 9 | (11.1) | 13 / | 1,625 | (0.8) | 0 / | 0 | — | 20 / | 1,981 | (1.0) |

| Impairment of coordination | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||||

| Respiratory | |||||||||||||||

| Bronchitis | 0 / | 0 | — | 0 / | 0 | — | 32 / | 407 | (7.9) | 0 / | 0 | — | 32 / | 407 | (7.9) |

| Pneumonia | 4 / | 191 | (2.1) | 7 / | 226 | (3.1) | 43 / | 1,416 | (3.0) | 18 / | 374 | (4.8) | 72 / | 2,207 | (3.3) |

| Hematologic | |||||||||||||||

| Anemia | 132 / | 311 | (42.4) | 52 / | 226 | (23.0) | 683 / | 3,516 | (19.4) | 150 / | 703 | (21.3) | 1,017 / | 4,756 | (21.4) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 0 / | 0 | — | 0 / | 0 | — | 98 / | 660 | (14.8) | 1 / | 374 | (0.3) | 99 / | 1,034 | (9.6) |

| Other | |||||||||||||||

| Focal abscess | 1 / | 47 | (2.1) | 0 / | 0 | — | 0 / | 0 | — | 0 / | 0 | — | 1 / | 47 | (2.1) |

| Pharyngitis | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||||

| Miscarriage | 0 / | 0 | — | 0 / | 0 | — | 1 / | 6 | (16.7) | 0 / | 0 | — | 1 / | 6 | (16.7) |

| Relapse | 6 / | 171 | (3.5) | 2 / | 129 | (1.6) | 71 / | 2,166 | (3.2) | 0 / | 0 | — | 79 / | 2,466 | (3.2) |

| Chronic carriage | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||||

| Seizure or convulsionsc | 14 / | 125 | (11.2) | 0 / | 0 | — | 94 / | 4,224 | (2.2) | 0 / | 0 | — | 108 / | 4,349 | (2.5) |

| Total complications | 260 / | 689 | (37.7) | 69 / | 226 | (30.5) | 2,135 / | 8,681 | (24.6) | 255 / | 739 | (34.5) | 2,719 / | 10,335 | (26.3) |

| Total Complications as described by study | 116 / | 348 | (33.3) | 24 / | 327 | (7.3) | 401 / | 3,028 | (13.2) | 128 / | 739 | (17.3) | 669 / | 4,442 | (15.1) |

Complications from Parry et al. Table 11

ND = No data. Data could not be abstracted as these complications were not described in any of the included articles.

Europe not shown due to the single study from Europe including participants diagnosed with stool and urine cultures, therefore it was not possible to distinguish complications among those diagnosed by culture of a normally sterile site. 101.

Outcomes of typhoid intestinal perforation

We identified 29 articles reporting surgical studies of TIP and an additional seven non-surgical studies provided data on CFR of TIP. Among the 36 combined surgical and non-surgical studies, 12 (33.3%) were in Asia, 23 (63.9%) in Africa, and one (2.8%) in the Americas. There were a total of 2,971 TIP cases, of which 2,921 (98.3%) were from surgical studies and 50 (1.7%) were from non-surgical studies. Of 2,971 TIP cases, 999 (33.6%) were in Asia, 1,967 (66.2%) in Africa, and 5 (0.2%) in the Americas. Of 2,971 TIP cases, 433 (14.6%) died. The median CFR of TIP across the 36 studies was 15.5% (6.7–24.1%).

Of 999 TIP cases in Asia, 46 (4.6%) died. The median CFR of TIP across 12 studies in Asia was 1.0% (0.0–8.4%). Of 1,967 TIP cases in Africa, 387 (19.7%) died. The median CFR of TIP across 23 studies in Africa was 20.0% (13.7–28.0%). Sex was available for 996 (99.7%) of 999 TIP cases in Asia; 704 (70.7%) were male compared to 292 (29.3%) female (Χ2=170.4; p<0.01). Sex was available for 1,826 (92.8%) of 1,967 TIP cases in Africa; 1,210 (66.3%) were male compared to 616 (33.7%) female (Χ2=193.2; p<0.01).

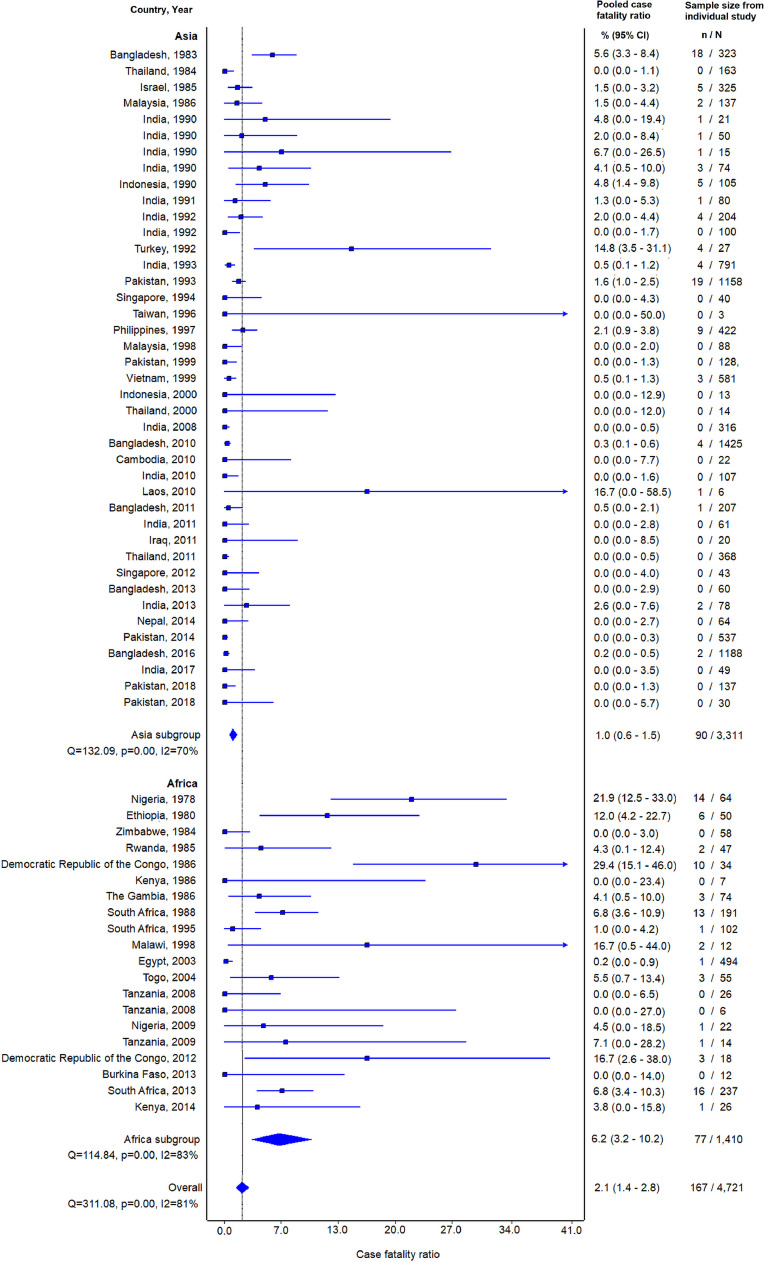

Typhoid fever mortality

Seventy-nine (94.0%) of 84 non-surgical study sites reported on mortality. Among 13,303 confirmed typhoid cases from studies reporting mortality, 250 died, for a CFR of 1.9% (Table 3). The pooled CFR estimate (95% CI; heterogeneity I2) among 79 studies reporting on mortality of confirmed typhoid fever was 2.0% (1.4–2.8%; 83.9%). The pooled CFR estimates for the Asia, Africa, Oceania, the Americas, and Europe regions were 0.9% (0.6–1.3%; 63.4%), 5.4% (2.7–8.9%; 83.4%), 7.2% (0.0–20.4%; 97.2%), 6.7% (0.0–19.9%; 94.4%), and 1.0% (0.0–6.8%; incalculable), respectively. Data on outcomes for multi-drug resistant Salmonella Typhi infection, outcomes and sub-regions and sub-regional forest plots for South-eastern Asia, Southern Asia, Eastern Africa, and Western Africa, including stratification in these sub-regions by age groups, are provided in Supplementary Appendix D and E, respectively.

Table 3.

Confirmed and probable cases of typhoid fever and case fatality ratio of confirmed typhoid fever, by United Nations region, 1965–2018.

| Africa | Americas | Asia | Europe | Oceania | All regions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed and probable typhoid fever | ||||||

| Study locations | 44 | 4 | 62 | 1 | 2 | 113 |

| Confirmed and probable cases | 3,642 | 554 | 11,973 | 30 | 739 | 16,938 |

| Median (IQR) cases per study | 50 (26–102.5) | 113.5 (9.8–242.3) | 79 (40–189) | a | 369.5 (367.3–371.8) | 63 (30–163) |

| Mortality among confirmed cases | ||||||

| Study locations | 22 | 3 | 51 | 1 | 2 | 84 |

| Confirmed cases | 1,700 | 544 | 10,295 | 25 | 739 | 13,303 |

| Number of deaths | 77 | 23 | 90 | 0 | 60 | 250 |

| CFR confirmed typhoid fever | 4.5 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 8.1 | 1.9 |

| Median CFR (IQR) | 4.2 (0.0–7.1) | 9.2 (4.8–15.7) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 8.1 (5.3–10.8) | 0.2 (0.0–4.2) |

| Pooled CFR (95% CI) | 5.4% (2.7–8.9%) | 6.7% (0.0–19.9%) | 0.9% (0.6–1.3%) | 0.8% (0.0–5.7%) | 7.2% (0.0–20.4%) | 2.0% (1.4–2.8%) |

No median; IQR = interquartile range; CI = confidence interval.

Sixty-seven (84.8%) of 79 non-surgical study sites were hospital-based, and 12 (15.2%) were population or community-based studies.37,38,60,73,84,90,96,118 Ten (83.3%) of 12 non-hospital study sites were located in Asia and two (16.7%) in Africa; one each in Kenya37 and Burkina Faso.60 No deaths were reported among 866 confirmed typhoid cases in the 12 non-hospital sites compared to 250 (2.0%) of 12,437 hospital-based confirmed cases (Χ2=16.7; p<0.01). The pooled CFR estimate for non-surgical hospital-based study sites was 2.4% (1.6–3.3%; 85.9%) compared to 0.2% (0.0–0.7%; 0.0%) for non-hospital sites. The pooled CRF estimate among hospital-based sites in Asia was 1.0% (0.6–1.5%; 69.7%) compared to 6.2% (3.2–10.2%; 83.5%) among hospital-based sites in Africa (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of typhoid case fatality ratio among non-surgical hospital-based study sites in Asia and Africa, by year, 1978–2018.

Care delays and outcome

Of 84 non-surgical studies, 20 (23.8%) reported a mean or median duration of fever, illness, or symptoms prior to care, as well as CFR. Two studies stratified duration of fever, one by age38 and the other by sex,66 for a total of 22 estimates. Of 22 estimates, seven (31.8%) were from Africa,30,37,59,66,81,122 12 (54.6%) from Asia,36,38,41,72,84,96,98,102,105,109,131 and one each (4.5%) were from the Americas,97 Europe,101 and Oceania.108 Among all 22 estimates, there was a statistically non-significant positive correlation of longer delay in care with increased CFR (r = 0.11; p = 0.64). Among the 12 estimates from Asia, there was a significant positive correlation between delay in care and CFR (r = 0.84; p<0.01) and a non-significant negative correlation between delay in care and CFR (−0.42; p = 0.35) among seven estimates from Africa. Scatterplots for delay in care are shown in Supplementary Appendix F.

Among 19 estimates in Asia and Africa, the mean (range) delay in care was 7.5 (2.0–16.4) days in Asia and 9.4 (6.7–11.0) days in Africa (p = 0.19). Among the 17 hospital-based estimates reporting delay in care metrics, the mean (range) delay was 9.3 (5.0–16.4) days, compared with 5.3 (2.0–10.4) days among five community-based estimates (p = 0.03).

Discussion

Our systematic review of published literature from 1980 through 2020 of predominantly hospitalized typhoid fever patients demonstrates a substantial prevalence of typhoid complications and death. We estimated a CFR of 2.0%, with significant variation by UN region. A considerable proportion of hospitalized patients with typhoid experienced complications. At the same time, delays in care, as measured by duration of fever or illness before presentation, were associated with increased CFR. However, we also identified significant differences in prevalence of complications and CFR between community-based and hospital-based studies, suggesting a bias towards poorer outcomes in hospital-based studies.

Among hospital-based non-surgical studies, the CFR of typhoid fever was significantly higher in Africa compared to Asia. Although there was no association between delay in care and CFR in Africa, our ability to detect an association was influenced by fewer data from Africa compared with Asia, where a statistically significant positive correlation was identified. Despite Africa comprising 39% of included study sites, it accounted for only 12% of all confirmed typhoid cases in our review. The limited data available on confirmed typhoid fever cases and smaller sample sizes of African studies may be due to lower typhoid incidence,23 compounded by the lack of capacity of many health care centers in Africa to obtain and perform blood cultures.133, 134, 135 Delays were longer in hospital-based sites compared to community-based sites, and such delays in diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and management of complications may contribute to the higher CFR identified among hospital studies. Others have linked duration of illness prior to hospitalization with increased prevalence of typhoid complications.19

Intestinal perforation was a common complication and an important contributor to typhoid mortality, especially in African studies where one in five patients with TIP died. A lack of access to surgical services and resources for post-operative management and intensive care, if needed, likely contribute to the high CFR seen among TIP patients.48,123,133,136 The prevalence of TIP as a complication of typhoid fever in non-surgical studies may be underestimated by our review, as some such studies were often done solely on medical wards or in hospitals that lacked surgical facilities.

A substantial limitation of our review was the preponderance of hospital-based studies. This introduced a bias towards higher prevalence of complications and higher CFR. However, care seeking behavior for febrile illnesses is not driven exclusively by severity. In some settings, poor transportation infrastructure, cost of healthcare, and difficulty in obtaining referrals can result in the sickest patients not reaching care.5, 6, 7 Alternatively, community-based studies alter the outcome towards the null by enhancing typhoid diagnosis and management, allowing early treatment before progression to severe and complicated disease.137 We attempted to limit other selection biases in non-surgical studies by stratifying by setting type, region and sub-region, and age, and by including only those that used culture of normally sterile sites to confirm typhoid fever. Among surgical studies, misclassification of non-typhoid causes of intestinal perforation as TIP are increasingly recognized.138 We were limited by the use of intra- and postoperative findings in classifying ileal perforations as TIP. We attempted to address this limitation by abstracting and presenting the criteria defining a case of TIP by study. Heterogeneity was high for pooled estimates of all studies. This was anticipated given the range of years, study designs, location, and age groups of included studies. However, when stratified by sub-region and by age group, heterogeneity was much lower.

Although our understanding of typhoid fever morbidity and mortality could be improved with more robust, community-based active surveillance studies, we demonstrate considerable typhoid fever morbidity and mortality that could be averted with prevention efforts. TCV represents a means to make rapid gains in prevention of typhoid fever complications and death.

Author contributions

JAC conceived the study. CSM and JAC developed the research protocol. CSM submitted the review to PROSPERO and performed the literature search. CSM and MB screened titles and abstracts, reviewed full texts, and performed data abstraction. JAC resolved discrepancies and reviewed the final dataset. CSM performed data analyses and prepared the first manuscript draft. MB prepared the abstract, ‘Research in Context’, and gave feedback on the first and subsequent drafts. JAC provided major revisions and comments to the first draft. All authors contributed to final edits and revisions prior to submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Funding

This work was supported by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) [grant OPP1151153], to JAC and CSM. JAC also received support from BMGF [grant numbers OPP1125993 and OPP1158210], the US National Institutes of Health [grant number R01AI121378], and the New Zealand Health Research Council through the e-ASIA Joint Research Program [grant number 16/697]. MB received support from the US National Institutes of Health [grant number T32 DK067872].

Role of the funder

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Leonardo Martinez, Stanford University, for his assistance in translating articles in Spanish text.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.10.030.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(22):1770–1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crump JA, Sjölund-Karlsson M, Gordon MA, Parry CM. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, laboratory diagnosis, antimicrobial resistance, and antimicrobial management of invasive Salmonella infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(4):901–937. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wain J, Hendriksen RS, Mikoleit ML, Keddy KH, Ochiai RL. Typhoid fever. The Lancet. 2015;385(9973):1136–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62708-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antillon M, Saad NJ, Baker S, Pollard AJ, Pitzer VE. The relationship between blood sample volume and diagnostic sensitivity of blood culture for typhoid and paratyphoid fever: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(suppl_4):S255–SS67. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snavely ME, Maze MJ, Muiruri C, Ngowi L, Mboya F, Beamesderfer J. Sociocultural and health system factors associated with mortality among febrile inpatients in Tanzania: a prospective social biopsy cohort study. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snavely ME, Oshosen M, Msoka EF, Karia FP, Maze MJ, Blum LS. "If you have no money, you might die": A qualitative study of sociocultural and health system barriers to care for decedent febrile inpatients in northern Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyer CA, Johnson C, Kaselitz E, Aborigo R. Using social autopsy to understand maternal, newborn, and child mortality in low-resource settings: a systematic review of the literature. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1413917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkhold M, Coulibaly Y, Coulibaly O, Dembélé P, Kim DS, Sow S. Morbidity and mortality of typhoid intestinal perforation among children in Sub-Saharan Africa 1995-2019: A scoping review. World J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05567-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahajan G, Kotru M, Sharma R, Sharma S. Usefulness of histopathological examination in nontraumatic perforation of small intestine. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(10):1837–1841. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1646-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crump JA. Progress in typhoid fever epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(Supplement_1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitzer VE, Feasey NA, Msefula C, Mallewa J, Kennedy N, Dube Q. Mathematical modeling to assess the drivers of the recent emergence of typhoid fever in Blantyre, Malawi. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(suppl_4):S251–S2S8. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luby SP, Faizan MK, Fisher-Hoch SP, Syed A, Mintz ED, Bhutta ZA. Risk factors for typhoid fever in an endemic setting, Karachi, Pakistan. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;120(2):129–138. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897008558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health O. Typhoid vaccines: WHO position paper, March 2018 - Recommendations. Vaccine. 2019;37(2):214–216. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitzer VE, Bowles CC, Baker S, Kang G, Balaji V, Farrar JJ. Predicting the impact of vaccination on the transmission dynamics of typhoid in South Asia: a mathematical modeling study. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2014;8(1):e2642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO). Typhoid vaccine prequalified. 3 January 2018.

- 16.Buckle GC, Walker CLF, Black RE. Typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever: Systematic review to estimate global morbidity and mortality for 2010. J Glob Health. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.02.010401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, Lee JS, Mogasale VV, Ramani E. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. The Lancet Global health. 2014;2(10):e570–ee80. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pieters Z, Saad NJ, Antillón M, Pitzer VE, Bilcke J. Case fatality rate of enteric fever in endemic countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(4):628–638. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz Espinoza LM, McCreedy E, Holm M, Im J, Mogeni OD, Parajulee P. Occurrence of Typhoid Fever Complications and Their Relation to Duration of Illness Preceding Hospitalization: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(Suppl 6):S435–SS48. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler T, Knight J, Nath SK, Speelman P, Roy SK, Azad MA. Typhoid fever complicated by intestinal perforation: a persisting fatal disease requiring surgical management. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7(2):244–256. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchello CS, Hong CY, Crump JA. Global typhoid fever incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(Supplement_2):S105–SS16. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United Nations Statistics D. Standard country or area codes for statistical use (M49). 2020.

- 25.Abantanga FA. Complications of typhoid perforation of the ileum in children after surgery. East Afr Med J. 1997;74(12):800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdool Gaffar MS, Seedat YK, Coovadia YM, Khan Q. The white cell count in typhoid fever. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44(1-2):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham G, Teklu B. Typhoid fever: clinical analysis of 50 Ethiopian patients. Ethiop Med J. 1981;19(2):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abucejo PE, Capeding MR, Lupisan SP, Arcay J, Sombrero LT, Ruutu P. Blood culture confirmed typhoid fever in a provincial hospital in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32(3):531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adesunkanmi AR, Ajao OG. The prognostic factors in typhoid ileal perforation: a prospective study of 50 patients. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1997;42(6):395–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afifi S, Earhart K, Azab MA, Youssef FG, El Sakka H, Wasfy M. Hospital-based surveillance for acute febrile illness in Egypt: a focus on community-acquired bloodstream infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(2):392–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agu K, Nzegwu M, Obi E. Prevalence, morbidity, and mortality patterns of typhoid ileal perforation as seen at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu Nigeria: an 8-year review. World J Surg. 2014;38(10):2514–2518. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmad Hatib NA, Chong CY, Thoon KC, Tee NW, Krishnamoorthy SS, Tan NW. Enteric fever in a tertiary paediatric hospital: A retrospective six-year review. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2016;45(7):297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali G, Rashid S, Kamli MA, Shah PA, Allaqaband GQ. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric complications in 791 cases of typhoid fever. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2(4):314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1997.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atamanalp SS, Aydinli B, Ozturk G, Oren D, Basoglu M, Yildirgan MI. Typhoid intestinal perforations: twenty-six year experience. World J Surg. 2007;31(9):1883–1888. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aziz S, Malik L. Emergence of multi-resistant enteric infection in a paediatric unit Of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(12):1848–1850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhutta ZA. Impact of age and drug resistance on mortality in typhoid fever. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(3):214–217. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breiman RF, Cosmas L, Njuguna H, Audi A, Olack B, Ochieng JB. Population-based incidence of typhoid fever in an urban informal settlement and a rural area in Kenya: implications for typhoid vaccine use in Africa. PLoS ONE. 2012 2012;7(1):e29119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks WA, Hossain A, Goswami D, Nahar K, Alam K, Ahmed N. Bacteremic typhoid fever in children in an urban slum, Bangladesh. Emerging Infect Dis. 2005;11(2):326–329. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.040422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmeli Y, Raz R, Schapiro JM, Alkan M. Typhoid fever in Ethiopian immigrants to Israel and native-born Israelis: a comparative study. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(2):213–215. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Koy M, Kataraihya JB, Jaka H, Mshana SE. Typhoid intestinal perforations at a University teaching hospital in Northwestern Tanzania: A surgical experience of 104 cases in a resource-limited setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandra R, Srinivasan S, Nalini P, Rao RS. Multidrug resistant enteric fever. J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;95(4):284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chansamouth V, Thammasack S, Phetsouvanh R, Keoluangkot V, Moore CE, Blacksell SD. The aetiologies and impact of fever in pregnant inpatients in Vientiane, Laos. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2016;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaudhary P, Kumar R, Munjewar C, Bhadana U, Ranjan G, Gupta S. Typhoid ileal perforation: a 13-year experience. Healthc Low Resour Settings. 2015;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen YH, Chen TP, Tsai JJ, Hwang KP, Lu PL, Cheng HH. Epidemiological study of human salmonellosis during 1991-1996 in southern Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1999;15(3):127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chheng K, Carter MJ, Emary K, Chanpheaktra N, Moore CE, Stoesser N. A prospective study of the causes of febrile illness requiring hospitalization in children in Cambodia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choo KE, Razif A, Ariffin WA, Sepiah M, Gururaj A. Typhoid fever in hospitalized children in Kelantan, Malaysia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1988;8(4):207–212. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1988.11748572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Contreras R, Ferreccio C, Sotomayor V, Astroza L, Berríos G, Ortiz E. [Typhoid fever in school children: by what measures is the modification of the clinical course due to oral vaccination?] Rev Med Chil. 1992;120(2):134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conventi R, Pellis G, Arzu G, Nsubuga JB, Gelmini R. Intestinal perforation due to typhoid fever in Karamoja (Uganda) Ann Ital Chir. 2018;89:138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crump JA, Ramadhani HO, Morrissey AB, Msuya LJ, Yang L-Y, Chow S-C. Invasive bacterial and fungal infections among hospitalized HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children and infants in northern Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(7):830–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crump JA, Ramadhani HO, Morrissey AB, Saganda W, Mwako MS, Yang L-Y. Invasive bacterial and fungal infections among hospitalized HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adults and adolescents in northern Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):341–348. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dheer G, Kundra S, Singh T. Clinical and laboratory profile of enteric fever in children in northern India. Trop Doct. 2012;42(3):154–156. doi: 10.1258/td.2012.110442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dworkin J, Saeed R, Mykhan H, Kanan S, Farhad D, Ali KO. Burden of typhoid fever in Sulaimania. Iraqi Kurdistan. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;27:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edino ST, Mohammed AZ, Uba AF, Sheshe AA, Anumah M, Ochicha O. Typhoid enteric perforation in north western Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2004;13(4):345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ganesh R, Janakiraman L, Vasanthi T, Sathiyasekeran M. Profile of typhoid fever in children from a tertiary care hospital in Chennai-South India. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77(10):1089–1092. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gbadoé AD, Lawson-Evi K, Dagnra AY, Guédénon K, Géraldo A, Djadou E. [Pediatric salmonellosis at the Tokoin's teaching hospital, Lomé (Togo)] Med Mal Infect. 2008;38(1):8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gedik E, Girgin S, Taçyildiz IH, Akgün Y. Risk factors affecting morbidity in typhoid enteric perforation. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393(6):973–977. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.González Ojeda A, Pérez Ríos A, Rodríguez M, de la Garza Villaseñor L. [The surgical complications of typhoid fever: a report of 10 cases] Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 1991;56(2):77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gordon MA, Walsh AL, Chaponda M, Soko D, Mbvwinji M, Molyneux ME. Bacteraemia and mortality among adult medical admissions in Malawi–predominance of non-Typhi Salmonellae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect. 2001;42(1):44–49. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green SD, Cheesbrough JS. Salmonella bacteraemia among young children at a rural hospital in western Zaire. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1993;13(1):45–53. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1993.11747624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guiraud I, Post A, Diallo SN, Lompo P, Maltha J, Thriemer K. Population-based incidence, seasonality and serotype distribution of invasive salmonellosis among children in Nanoro, rural Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 2017 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harichandran D, Dinesh KR. Antimicrobial susceptibility profile, treatment outcome and serotype distribution of clinical isolates of Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica: a 2-year study from Kerala. South India. Infect Drug Resist. 2017 2017;10:97–101. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S126209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hosoglu S, Aldemir M, Akalin S, Geyik MF, Tacyildiz IH, Loeb M. Risk factors for enteric perforation in patients with typhoid Fever. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(1):46–50. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kadhiravan T, Wig N, Kapil A, Kabra SK, Renuka K, Misra A. Clinical outcomes in typhoid fever: adverse impact of infection with nalidixic acid-resistant Salmonella Typhi. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keddy KH, Sooka A, Smith AM, Musekiwa A, Tau NP, Klugman KP. Typhoid fever in South Africa in an endemic HIV setting. PLoS ONE. 2016 2016;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keenan JP, Hadley GP. The surgical management of typhoid perforation in children. Br J Surg. 1984;71(12):928–929. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800711203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khan M, Coovadia YM, Connolly C, Sturm AW. Influence of sex on clinical features, laboratory findings, and complications of typhoid fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61(1):41–46. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan MI, Soofi SB, Ochiai RL, Khan MJ, Sahito SM, Habib MA. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and patterns of drug resistance of Salmonella Typhi in Karachi, Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6(10):704–714. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurlberg G, Frisk B. Factors reducing mortality in typhoid ileal perforation. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85(6):793–795. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90458-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laditan AA, Alausa KO. Problems in the clinical diagnosis of typhoid fever in children in the tropics. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1981;1(3):191–195. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1981.11748087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lepage P, Bogaerts J, Van Goethem C, Ntahorutaba M, Nsengumuremyi F, Hitimana DG. Community-acquired bacteraemia in African children. Lancet. 1987;1(8548):1458–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leung DT, Bogetz J, Itoh M, Ganapathi L, Pietroni MAC, Ryan ET. Factors associated with encephalopathy in patients with Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi bacteremia presenting to a diarrheal hospital in Dhaka. Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(4):698–702. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Limpitikul W, Henpraserttae N, Saksawad R, Laoprasopwattana K. Typhoid outbreak in Songkhla, Thailand 2009-2011: clinical outcomes, susceptibility patterns, and reliability of serology tests. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin FY, Vo AH, Phan VB, Nguyen TT, Bryla D, Tran CT. The epidemiology of typhoid fever in the Dong Thap Province, Mekong Delta region of Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(5):644–648. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Magsi AM, Iqbal M, Khan S, Parveen S, Khan MI, Shamim M. Frequency, presentation and outcomes of typhoid ileal perforation. Indo American Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2019;6(6):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malik AS. Complications of bacteriologically confirmed typhoid fever in children. J Trop Pediatr. 2002;48(2):102–108. doi: 10.1093/tropej/48.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maltha J, Guiraud I, Kaboré B, Lompo P, Ley B, Bottieau E. Frequency of severe malaria and invasive bacterial infections among children admitted to a rural hospital in Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mathura KC, Gurubacharya DL, Shrestha A, Pant S, Basnet P, Karki DB. Clinical profile of typhoid patients. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2003;1(2):135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mishra S, Patwari AK, Anand VK, Pillai PK, Aneja S, Chandra J. A clinical profile of multidrug resistant typhoid fever. Indian Pediatr. 1991;28(10):1171–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mock C, Visser L, Denno D, Maier R. Aggressive fluid resuscitation and broad spectrum antibiotics decrease mortality from typhoid ileal perforation. Trop Doct. 1995;25(3):115–117. doi: 10.1177/004947559502500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mock CN, Amaral J, Visser LE. Improvement in survival from typhoid ileal perforation. Results of 221 operative cases. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):244–249. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199203000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mtove G, Amos B, von Seidlein L, Hendriksen I, Mwambuli A, Kimera J. Invasive salmonellosis among children admitted to a rural Tanzanian hospital and a comparison with previous studies. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e9244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mukherjee P, Mukherjee S, Dalal BK, Haldar KK, Ghosh E, Pal TK. Some prospective observations on recent outbreak of typhoid fever in West Bengal. J Assoc Physicians India. 1991;39(6):445–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Muthumbi E, Morpeth SC, Ooko M, Mwanzu A, Mwarumba S, Mturi N. Invasive salmonellosis in Kilifi, Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 4):S290–S301. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naheed A, Ram PK, Brooks WA, Hossain MA, Parsons MB, Talukder KA. Burden of typhoid and paratyphoid fever in a densely populated urban community, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(Suppl 3):e93–e99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ndayizeye L, Ngarambe C, Smart B, Riviello R, Majyambere JP, Rickard J. Peritonitis in Rwanda: Epidemiology and risk factors for morbidity and mortality. Surgery. 2016;160(6):1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nesbitt A, Mirza NB. Salmonella septicaemias in Kenyan children. J Trop Pediatr. 1989;35(1):35–39. doi: 10.1093/tropej/35.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nilsson E, Olsson S, Regner S, Polistena A, Ali A, Dedey F. Surgical intervention for intestinal typhoid perforation. G Chir. 2019;40(2):105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nuhu A, Dahwa S, Hamza A. Operative management of typhoid ileal perforation in children. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7(1):9–13. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.59351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Obaro S, Lawson L, Essen U, Ibrahim K, Brooks K, Otuneye A. Community acquired bacteremia in young children from central Nigeria–a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ochiai RL, Acosta CJ, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Baiqing D, Bhattacharya SK, Agtini MD. A study of typhoid fever in five Asian countries: disease burden and implications for controls. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(4):260–268. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.039818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oh HM, Masayu Z, Chew SK. Typhoid fever in hospitalized children in Singapore. J Infect. 1997;34(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)94283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oheneh-Yeboah M. Postoperative complications after surgery for typhoid ileal perforation in adults in Kumasi. West Afr J Med. 2007;26(1):32–36. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v26i1.28300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ollé-Goig JE, Ruiz L. Typhoid fever in rural Haiti. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1993 1993;27(4):382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Osifo OD, Ogiemwonyi SO. Typhoid ileal perforation in children in Benin city. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7(2):96–100. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.62857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ouedraogo S, Ouangre E, Zida M. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic features of typhoid intestinal perforation in a rural environment of Burkina Faso. Med Sante Trop. 2017;27(1):67–70. doi: 10.1684/mst.2017.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Owais A, Sultana S, Zaman U, Rizvi A, Zaidi AKM. Incidence of typhoid bacteremia in infants and young children in southern coastal Pakistan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(11):1035–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Palacios Malmaceda PG, Vela Acosta JJ, Gutiérez Arrasco W. [Typhoid fever in children under 2 years of age] Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1981;38(3):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Parry CM, Thompson C, Vinh H, Chinh NT, Phuong LT, Ho VA. Risk factors for the development of severe typhoid fever in Vietnam. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Petersiel N, Shresta S, Tamrakar R, Koju R, Madhup S, Shresta A. The epidemiology of typhoid fever in the Dhulikhel area, Nepal: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Phoba MF, De Boeck H, Ifeka BB, Dawili J, Lunguya O, Vanhoof R. Epidemic increase in Salmonella bloodstream infection in children, Bwamanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(1):79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Prieto López I, de la Fuente Aguado J, González Díaz I, López Myragalla I, Martínez Vázquéz C, Sopeña Pérez-Argüelles B. [Infection by Salmonella Typhi in the southern area of Ponteverde] An Med Interna. 1994;11(2):71–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Punjabi NH, Taylor WRJ, Murphy GS, Purwaningsih S, Picarima H, Sisson J. Etiology of acute, non-malaria, febrile illnesses in Jayapura, northeastern Papua, Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(1):46–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.10-0497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qamar FN, Yousafzai MT, Sultana S, Baig A, Shakoor S, Hirani F. A retrospective study of laboratory-based enteric fever surveillance, Pakistan, 2012-2014. J Infect Dis. 2018 2018;218(suppl_4):S201–S2S5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rao PS, Rajashekar V, Varghese GK, Shivananda PG. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhi in rural southern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48(1):108–111. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rasaily R, Dutta P, Saha MR, Mitra U, Lahiri M, Pal SC. Multi-drug resistant typhoid fever in hospitalised children. Clinical, bacteriological and epidemiological profiles. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10(1):41–46. doi: 10.1007/BF01717450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rodrigues C, Mehta A, Mehtar S, Blackmore PH, Hakimiyan A, Fazalbhoy N. Chloramphenicol resistance in Salmonella Typhi. Report from Bombay. J Assoc Physicians India. 1992;40(11):729–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rogerson SJ, Spooner VJ, Smith TA, Richens J. Hydrocortisone in chloramphenicol-treated severe typhoid fever in Papua New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85(1):113–116. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.S AG, Parry CM, Crump JA, Rosa V, Jenney A, Naidu R. A retrospective study of patients with blood culture-confirmed typhoid fever in Fiji during 2014-2015: epidemiology, clinical features, treatment and outcome. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113(12):764–770. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trz075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Saeed N, Usman M, Khan EA. An overview of extensively drug-resistant Salmonella Typhi from a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5663. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saha S, Islam MS, Sajib MSI, Saha S, Uddin MJ, Hooda Y. Epidemiology of typhoid and paratyphoid: Implications for vaccine policy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 2019;68(Suppl 2):S117–SS23. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Seçmeer G, Kanra G, Cemeroğlu AP, Ozen H, Ceyhan M, Ecevit Z. Salmonella Typhi infections. A 10-year retrospective study. Turk J Pediatr. 1995;37(4):339–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shahunja KM, Leung DT, Ahmed T, Bardhan PK, Ahmed D, Qadri F. Factors associated with non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteremia versus typhoidal Salmonella bacteremia in patients presenting for care in an urban diarrheal disease hospital in Bangladesh. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shetty AK, Mital SR, Bahrainwala AH, Khubchandani RP, Kumta NB. Typhoid hepatitis in children. J Trop Pediatr. 1999;45(5):287–290. doi: 10.1093/tropej/45.5.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sinha A, Sazawal S, Kumar R, Sood S, Reddaiah VP, Singh B. Typhoid fever in children aged less than 5 years. Lancet. 1999;354(9180):734–737. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sucindar M, Kumaran SS. Profile of culture positive enteric fever in children admitted in a tertiary care hospital. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 2017;6(88):6112–6117. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sulaiman K, Sarwari AR. Culture-confirmed typhoid fever and pregnancy. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sur D, Barkume C, Mukhopadhyay B, Date K, Ganguly NK, Garrett D. A retrospective review of hospital-based data on enteric fever in India, 2014-2015. J Infect Dis. 2018 2018;218(suppl_4):S206–SS13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sur D, von Seidlein L, Manna B, Dutta S, Deb AK, Sarkar BL. The malaria and typhoid fever burden in the slums of Kolkata, India: data from a prospective community-based study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(8):725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tade AO, Ayoade BA, Olawoye AA. Pattern of presentation and management of typhoid intestinal perforation in Sagamu, South-West Nigeria: a 15 year study. Niger J Med. 2008;17(4):387–390. doi: 10.4314/njm.v17i4.37417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Talabi AO, Etonyeaku AC, Sowande OA, Olowookere SA, Adejuyigbe O. Predictors of mortality in children with typhoid ileal perforation in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30(11):1121–1127. doi: 10.1007/s00383-014-3592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Thisyakorn U, Mansuwan P, Taylor DN. Typhoid and paratyphoid fever in 192 hospitalized children in Thailand. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141(8):862–865. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460080048025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Topley JM. Mild typhoid fever. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61(2):164–167. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Uba AF, Chirdan LB, Ituen AM, Mohammed AM. Typhoid intestinal perforation in children: a continuing scourge in a developing country. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23(1):33–39. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ugochukwu AI, Amu OC, Nzegwu MA. Ileal perforation due to typhoid fever - review of operative management and outcome in an urban centre in Nigeria. Int J Surg. 2013;11(3):218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ugwu BT, Yiltok SJ, Kidmas AT, Opaluwa AS. Typhoid intestinal perforation in north central Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2005;24(1):1–6. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v24i1.28152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Usang UE, Inyang AW, Nwachukwku IE, Emehute J-DC. Typhoid perforation in children: an unrelenting plague in developing countries. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017;11(10):747–752. doi: 10.3855/jidc.9304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vala S, Shah U, Ahmad SA, Scolnik D, Glatstein M. Resistance patterns of typhoid Fever in children: A longitudinal community-based study. Am J Ther. 2016;23(5):e1151–e1154. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.van den Bergh ET, Gasem MH, Keuter M, Dolmans MV. Outcome in three groups of patients with typhoid fever in Indonesia between 1948 and 1990. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4(3):211–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.43374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.van der Werf TS, Cameron FS. Typhoid perforations of the ileum. A review of 59 cases, seen at Agogo Hospital, Ghana, between 1982 and 1987. Trop Geogr Med. 1990;42(4):330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Weeramanthri TS, Corrah PT, Mabey DC, Greenwood BM. Clinical experience with enteric fever in The Gambia, West Africa 1981-1986. J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;92(4):272–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wongsawat J, Pancharoen C, Thisyakorn U. Typhoid fever in children: experience in King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(12):1247–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yu AT, Amin N, Rahman MW, Gurley ES, Rahman KM, Luby SP. Case-fatality ratio of blood culture-confirmed typhoid fever in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Infect Dis. 2018 2018;218(suppl_4):S222–S2S6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.GlobalSurg C. Management and outcomes following surgery for gastrointestinal typhoid: An international, prospective, multicentre cohort study. World J Surg. 2018;42(10):3179–3188. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Anyanwu L-J, Mohammad A, Abdullahi L, Farinyaro A, Obaro S. Determinants of postoperative morbidity and mortality in children managed for typhoid intestinal perforation in Kano Nigeria. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2018;53(4):847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Abantanga FA, Nimako B, Amoah M. Perforations of the gut in children as a result of enteric fever: A 5-years single institutional review. Annals of Pediatric Surgery. 2009;5(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ekenze SO, Anyanwu PA, Ezomike UO, Oguonu T. Profile of pediatric abdominal surgical emergencies in a developing country. Int Surg. 2010;95(4):319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Crump JA, Youssef FG, Luby SP, Wasfy MO, Rangel JM, Taalat M. Estimating the incidence of typhoid fever and other febrile illnesses in developing countries. Emerging Infect Dis. 2003;9(5):539–544. doi: 10.3201/eid0905.020428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Poornima R, Venkatesh KL, Nirmala M.V.G, Hassan N. Clinicopathological study of Ileal perforation: study in tertiary center. Int Surg J. 2017;4(2):543. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.