Abstract

Background & Objective:

Dantrolene, a ryanodine receptor antagonist, is primarily known as the only clinically acceptable and effective treatment for malignant hyperthermia (MH). Inhibition of ryanodine receptor (RyR) by dantrolene decreases the abnormal calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) or endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where RyR is located on. Recently, emerging researches on dissociated cells, brains slices, live animal models and patients demonstrate that altered RyR expression and function can also play a vital role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Therefore, dantrolene is now widely studied as a novel treatment for AD, targeting the blockade of RyR channels or other alternative pathways, such as the inhibitory effects of NMDA glutamate receptors and the effects of ER-mitochondria connection. However, the therapeutic effects are not consistent.

Conclusion:

In this review, we focus on the relationship between the altered RyR expression and function and the pathogenesis of AD, and the potential application of dantrolene as a novel treatment for the disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dantrolene, therapy, ryanodine receptor, calcium, amyloid

1. INTRODUCTION

Since its first description in the 19th century, AD is one the most common neurodegenerative diseases among the elderly population. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), the global prevalence of AD will quadruple in the succeeding decades, reaching 14 million patients by 2050 [1]. Leading to emotional instability, cognitive deficits, memory loss, and motor activity degeneration, AD devastates patients’ lives. Along with the high incidence rate, the disease leads to high mortality, with death occurring within 3–9 years after diagnosis [2]. The therapies for AD patients can be a huge economic, physical, and psychological burden for their families and society [3]. Thus, there are worldwide concerns for the pathology and treatment of AD.

Dantrolene, the only clinical acceptable treatment for MH, is well known by anesthesiologists. MH is a fatal condition prompted by volatile inhaled anesthetics and succinylcholine [4]. It’s demonstrated that ryanodine receptor (RyR) genetic mutations cause MH susceptibility, in which anesthetics trigger aberrant Ca2+ release from SR in the skeletal muscles [5, 6]. In 1979, dantrolene sodium, a RyR antagonist, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of MH [7]. Since then, dantrolene has been known to reverse the symptoms effectively and reduce mortality from from 70–80% in the 1970’s to <5% nowadays, with relatively tolerable side effects [8, 9].

Besides its effective treatment on MH, emerging studies on dissociated cells, brains slices, and animal models indicate that dantrolene has the potential to protect cells and tissues against damage induced by ischemia, trauma, seizure, sepsis, and cardiac failure [10, 11]. This suggests that abnormal Ca2+ from the primary intracellular calcium stores, SR in muscles, or ER in neurons may be a commonly used pathway to induce cell damage. Recent studies illustrating the effectiveness of dantrolene to ameliorate amyloid pathology and learning and memory deficits in animal models of AD triggered amounting interest in investigating the potential use of dantrolene for treatment of AD, a rapidly increasing and devastating neurodegenerative disease without effective treatment. In this review, we summarize the potential roles of altered RyR expression and function in the pathogenesis and progression of AD and dantrolene as a novel treatment for AD.

2. PATHOGENESIS OF AD

The accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide [12, 13]. and hyperphosphorylated tau protein [14] plays an important role in the onset and aggression of AD, in both sporadic and familial AD (SAD, FAD). Amyloid pathology in FAD is usually initiated by hereditary mutations of the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), Presenilin 1(PS1), or Presenilin 2 (PS2) [12, 15, 16]. APP cleavage by the β- and γ-secretase forms Aβ, and the accumulation of Aβ forms the main component known as amyloid plaque. The tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation leads to intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). Both amyloid and tau pathological protein aggregation are considered the typical hallmarks of AD. However, it’s still unclear whether Aβ peptide is the trigger of AD pathogenesis or a downstream change of burdensome alterations that contribute to neuron loss and synaptic dysfunction [17]. Accordingly, recent therapies focused on reducing Aβ formation and plaques have all failed to prevent, arrest, or reverse the disease in patients, despite all the decades of research [13, 18].

A large variety of neuronal processes and functions depend on calcium signaling. Calcium signaling plays a crucial role in cell growth, differentiation, metabolism, exocytosis, and apoptosis [19, 20]. Generally, the cytosolic free calcium is kept at a low level of approximately 100nM, extracellular calcium is kept at a higher level between 1.2–2mM, and calcium inside the intracellular stores is kept at about 100–500μM [21]. The largest intracellular calcium storage is the ER. In the 80’s, a hypothesis was proposed which stated that the disruption of intracellular calcium homeostasis could play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD [22]. Since then, emerging evidence from experiments both in vivo and in vitro have reported that the alterations in calcium signaling happen in both SAD and FAD. The mechanisms linking calcium dysregulation to AD pathogenesis may involve the following aspects: i) a pathological elevation of cytosolic calcium concentration which increases Aβ production [23, 24] ii) the disruption of cytosolic calcium homeostasis by Aβ [25] iii) mutation of the presenilins disrupts calcium signaling, which is best known for disruption of ER calcium homeostasis [26] and its normal connection and relationship with mitochondria [27] iv) calcium-dependent tau phosphorylation [28].

RyRs, ER-resident calcium-release channels, are one of the main regulators of intracellular calcium signaling, which maintain calcium homeostasis [29]. Thus, the impact of RyRs and the therapeutic effects of dantrolene, an RyR antagonist, on AD have been wildly observed recently.

3. ALTERATIONS OF RyR IN AD

The integrity of the RyR in Alzheimer’s disease brains was first investigated in 1999. The authors detected and compared the ryanodine binding and function in particulate fractions in control and AD brains. The research discovered that there was increased RyR2 binding and function in early stages of the disease, and a subsequent decline, which correlated with the advancement of neurofibrillary tangles forming and amyloid accumulation [30]. Recently, another study investigated the level of RyR2 mRNA expression in AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in patients’ brains. A significantly increased RyR2 mRNA expression was found in middle temporal cortices of MCI and AD brains that may increase vulnerability to apoptosis [31].

Multiple investigations on the alteration of RyRs expression in several AD models and cell cultures have been reported. Although a consistent conclusion can not be reached, which may due to the different models used in different studies, the altered expression of RyRs both in vivo and in vitro has widely been demonstrated. A more than fivefold increase in the RyR2 isoform was found in the hippocampus of 6–8 weeks old 3xTg-AD mice relative to the Non-Tg controls [32, 33]. Similarly, Benedicte also found a significant increase in RyR2 expression in the cortex of 12–15-month-old Tg2567 mice [34]. In another study on 4–4.5-month-old TgCRND8 mice, the authors detected an increase of RyR3 transcription and protein levels in the hippocampus and cortex of the mice brains, while neither RyR1 nor RyR2 changed [35]. Increased expression of RyR mRNA, including all the isoforms, was also discovered in the cells derived from APPswe and APP695 mice [34].

It has been suggested that an increased expression and function of RyR are a compensation for PS leak function. Liu generated APPPS1*RyR3−/− mutant mice and compared their network excitability and AD pathology to wild-type mice. It was interesting that the deletion of RyR3 in APPPS1 mice could have different effects at different ages. In young mice, negative synaptic plasticity and increased Aβ deposit were found. Subsequently, it leads to neuronal excitation and aggressive AD progression. In contrast, the deletion of RyR3 in older mice had a reversed effect. The negative synaptic plasticity and Aβ accumulation decreased and neuronal excitation and aggressive AD progress was rescued. Clinically, spontaneous seizure attacks had been decreased [36]. Zhang showed similar results of how the inhibition of RyRs expression and function led to increased Aβ accumulation, negative synaptic plasticity, and neuron degeneration in the hippocampal and cortical regions of the brain when treating APPPS1 mice with dantrolene (an RyR inhibitor) from 2 to 8 months of age [33]. In Charlene’s study, decreased RyR3 level in TgCRND8 neurons induced neuronal death, which was not found in wild-type mice neurons [37]. These results indicate that the increased RyR expression may be neuroprotective in the early stage of AD.

4. RyR-MEDIATED CALCIUM DISRUPTIONS

Altered calcium signaling performs a fundamental function in the pathogenesis of AD [38, 39]. Enhanced ryanodine-mediated calcium release has been demonstrated in several AD mouse models. In non-transgenic mice, the leak of calcium from ER was primarily through inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) rather than calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) through RyR [40, 41]. In contrast, the overload intracellular calcium signaling in AD mice was primarily due to the CICR through RyR, and was also related to altered RyR expression and function [40, 41].

The RyR-mediated calcium disruption has been linked to synaptic deficits. Chan and his colleagues found a significantly increased RyR expression level in PC12 cell harboring PS1 mutation and hippocampal neurons derived from PS1ki mice. The increased level of RyR might have contributed to the aberrant calcium leak from ER when the cells were stimulated with caffeine [42]. The similar intensified reaction to caffeine was also observed in other AD mice model, both in vivo and in vitro (PS2-N1141 mutation mice and PS2-N1141/APP Swedish mutation mice) [43]. In another study, the authors demonstrated that the excessive leak of calcium from ER resulted in the accumulation of Aβ, triggering a downstream cascade reaction that the mitochondrial activity affected and mitochondrial-induced apoptosis pathway perturbed [44]. On the contrary, reduced RyR expression levels and functions are detected in the PS conditional double knockout hippocampal neuron. The phenomenon contributed to impaired RyR-mediated calcium release and presynaptic deficits, proposing the vital role of RyR in the regulation of calcium signals and synaptic plasticity by PS [45]. Ivan and his colleagues investigated the relationship between synaptic transmission and calcium released through RyR in glutamatergic synapses using 3xTg-AD and TAS/TPM AD mice cortical brain slices [46]. They found that increased RyR-mediated calcium signals in synapses of neurons were associated with synaptic dysfunction in AD mice brains. In addition, synaptic-evoked postsynaptic calcium responses were greater in the AD strains, as were calcium signals generated from DMDAR activation. Thus, the authors proposed that PS1 induced increased RyR signaling and subsequent CICR via NMDAR-mediated calcium influx altered synaptic function [46]. It should be noted that dantrolene has also been demonstrated to inhibit NMDA receptor, [47] which may contribute to its ability to ameliorate the NMDA mediated elevation of cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]c) by as much as 70% [48]. Therefore, dantrolene may have multiple effects to correct the disrupted intracellular calcium homeostasis, although the inhibition of RyR plays a primary role.

5. RyR AND AMYLOID β Processing

PS is a family of associated multi-transmembrane proteins that act as part of the catalyst cores of the γ-secretase in amyloid precursor protein (APP) cleavage, generating Aβ peptides. In many studies, it was demonstrated that PS mutants disrupted calcium homeostasis through RyRs [40–42, 45, 46]. To study the molecular mechanism underlying this regulation, the laboratory of Peter Koulen produced a soluble cytoplasmic N-terminal fragment of both PS1 (PS1 NTF1–28) and PS2 (PS21–87), and studied their effects on single-channel currents of mouse brain RyRs. The results suggested that both PS1 NTF and PS2 NTF raised both mean currents and open probability of single brain RyR channels. Both PS1 NTF and PS2 NTF interacted with the RyR in a calcium-dependent manner. PS2 NTF affected RyR activity at Ca2+ concentrations larger than physiologically normal or healthy cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, while the RyR potentiation by PS1 NTF was overruled by receptor desensitization at high Ca2+ concentration [49, 50]. In a further study, the authors found that different function and isotype-specificity is the result of four cysteines absent in PS1NTF, however, present in PS2TNF. Site-directed mutagenesis fixed on these cysteines converted PS1NTF to PS2NTF function and vice versa, indicating that there is differential RyR binding [51].

In 1999, Kelliher found that the level of the RyR parallelled with the process of AD Aβ pathologies in human brains. He supposed that RyRs may be fundamental to the progression of Aβ pathologies [30]. To investigate whether APP mutation disrupts Aβ deposit and accumulation via perturbing ER Ca2+ homeostasis, Benedicte and colleagues analyzed the expression of the RyR, the subcellular Ca2+ signals and their impacts on APP metabolism, and Aβ peptide production using neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell lines. In Tg2576 mice harboring the Swedish double mutation (K670N/M671L), the overexpression of APP-induced increased RyR level and the aberrant leak of calcium from ER through RyR consequently. Furthermore, whether the Tg2576 mice were treated with dantrolene or the neurons derived from Tg2576 mice were cultured with dantrolene, the reduced Aβ burden was found both intracellular and extracellular. These results documented the key role of RyR in Aβ production [34, 52]. In further in vitro study using APPswe-expressing SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, the interaction between RyR modification, cytosolic calcium and Aβ production was revealed. The authors found Aβ-mediated RyR modifications (oxidation, phosphorylation, and nitrosylation) and increased cytosolic Ca2+ via β2-adrenergic signaling. Meanwhile, RyR2 remodeling, in turn, increased Aβ production. Similarly, βAPP processing and Aβ deposit were suppressed when RyR was pharmacologically inhibited [53]. In another study, the authors incubated the cortical neurons with Aβ synthetic peptides with thapsigargin (a non-competitive ER Ca ATPase) or dantrolene. It was observed that significantly increased cytosolic calcium leaked from ER in the neurons, when the cells were incubated with Aβ and thapsigargin at the same time. Consequently, a larger number of cell deaths were found through caspase-3 pathway. Meanwhile, these neurotoxic effects induced by Aβ were rescued by dantrolene. Obviously, the involvement of Ca2+ release from ER-mediated by RyR in Aβ toxicity could cause Aβ induced neuronal death [54, 55].

6. OTHER PATHWAYS RELATED TO ALTERED RYR OR PERTURBED CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS

6.1. Nitric Oxide (NO)

NO is one of the most important intracellular messengers that regulate numerous physiological process, including neuronal development and function. It was demonstrated that the disrupted neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) dimerization proceeded the occurrence of synaptic dysfunction in AD mice model, and so was the increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [56]. Calcium release from ER was increased by NO via RyR, [57–59] which consequently increased the calcium influx across the plasma membrane [57]. The effects of NO on RyR might be mediated via Snitrosylation [58] or cyclic adenosine disphosphate ribose (cADPR) [57]. As a result, the plasma concentration of calcium was markedly increased due to NO, leading to neuronal toxicity, which could be rescued by both genetic silencing of RyR and dantrolene treatment [58]. NO was demonstrated to promote neuropathogenesis of AD. Genetic ablation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) protected the transgenic mice brain from amyloid β accumulation and plaque forming [60]. Prolonged exposure of NO to SH-SY5Y cells induced tau aggregates [61]. However, NO might also be neuroprotective by elevating intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) [60–63]. Several studies have proved that the lack of NOS2 gene would increase the amyloid β levels and tau aggregation, accompanied with cognitive dysfunction [64, 65]. Another study demonstrated that reduced NO synthesis would exacerbate the impairment of hippocampal synaptic plasticity in presymptomatic 3XTG-AD mice. At the same time, the increased nNOS levels were reversed by chronic (4 weeks) dantrolene treatment [66]. So it was proposed that, to some extent or at a certain stage of AD, NO signaling might act as a neuroprotective role.

6.2. Altered Immune Function

Emerging evidence has demonstrated the roles of altered immune function in the pathogenesis of AD. It was demonstrated that the senile plaques were surrounded with the activated microglia that had the capability to clear the plaques [67, 68]. However, activated microglia also induce neuronal degeneration and synapse loss [69], which promote the pathogenesis of AD. The hyperactivated astrocytes were also found in AD mice hippocampi [70]. The increased synthesis of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by activated astrocytes, such as necrosis factor-a (TNF-a) [71] and IL-1, [72] induces the intracerebral inflammatory response. Furthermore, in vitro study suggested that microglia phagocytosis was suppressed by astrocytes, leading to the less clearance of senile plaques [73]. Vice versa, amyloid was proved to stimulate microglia and astrocytes to secrete a variety of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL6, IL8, TGF-β, MCP-1 and MIP [74, 75], etc. While the inflammatory response induced by microglia and astrocytes promotes the pathogenesis of AD, amyloid leads to inflammatory release, consequently forming a vicious cycle. Interestingly, perturbed calcium homeostasis is also proved in microglia and astrocytes [76, 77]. Also, dantrolene treatment appears to modulate the inflammatory secretion and neuroinflammation through calcium pathway [78, 79].

6.3. ER-Mitochondria Communication

There is a physical connection between the two main organelles regulating calcium homeostasis, mitochondria and ER, called mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAM) [80]. It was found to be a high concentration of calcium microdomain,(81) where located enriched RyR [82, 83]. Dantrolene treatment inhibits mitochondrial calcium uptake in neurons, and thus affects the calcium concentration [84]. Naturally, it is expected and proved that mitochondrial dysfunction and altered ER-mitochondrial communication do induce calcium dysregulation in AD [85]. Both MAM and ER-mitochondrial communication is markedly increased in the cells from both FAD and SAD patients [86]. Mitochondrial-associated presenilins [87] and secretase activity [88] participate in the formation of APP. So it is hypothesized the altered MAM function and upregulated ER-mitochondrial communication are the upstream cause of AD.

6.4. Dantrolene – a Novel Treatment for AD

Given the above, the in vivo and in vitro AD studies demonstrated that altered RyRs were implicated in calcium release from ER to cytosol in synaptic plasticity and function, thus, contributing to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss underlying cognitive deficits associated with the disease. RyRs were also proven to play a role in AD development, including neurofibrillary and Aβ pathologies. Therefore, pharmacological approaches targeting the blockade of RyR channels have become a novel therapeutic approach for Alzheimer’s disease.

It was first reported, in 2012, to use early and long-term treatment of dantrolene in a murine model of AD in Wei’s lab [89]. The researchers published a series of studies using early and chronic treatment (from ages 2–13 months or from ages 15–21 months) of dantrolene in 3xTg AD mouse models. Dantrolene significantly decreased both intraneuronal amyloid burden and extraneuronal plaque, and abolished memory and learning loss in 3xTg AD mice [89–91]. In Chami’s lab, they used the treatment of dantrolene in APP-swe-expressing mice from the ages 12 to 15 months, which reduced Aβ production and number of senile plaques, and slowed down learning and memory deficits [34]. In an in vitro study, dantrolene diminished Aβ load in APPswe primary cultured neurons, which was due to APP phosphorylation and decreased β- and γ-secretase activities [34, 52].

It was also demonstrated that dantrolene preserved the synaptic defects. Chakroborty and colleagues used sub-chronically treatment of dantrolene in 3xTg AD models (from ages 2 to 3 months). The disrupted hippocampal ER calcium homeostasis in synaptic structures was completely rescued by dantrolene in AD mice, indicating synaptic function preserved. Dantrolene could also reduce Aβ accumulation in the hippocampal and cortical region in AD mice [92]. The Aβ oligomer-induced cell death was also prevented with the presence of dantrolene in other studies [54, 55]. Zhang and colleagues in Bezeprozvanny’s lab discovered the impaired mushroom spines in PS1-M146V knock-in (KI) FAD mice, which was caused by enhanced CICR. Then they demonstrated that the structural deficit in KI neurons was reversed by dantrolene. The long-term potentiation defects in KI hippocampal slices were also rescued [93]. These results may be responsible for the rescued memory and learning defects in AD by dantrolene [54, 55, 92, 93].

Bezeprozvanny’s group demonstrated a dual effect of RyR blockade treatment. However, both structural plasticity defects and long-term potentiation defects in KI hippocampal slices were rescued by incubation of dantrolene [93]. For the in vivo study, they administered the APPPS1 mice with dantrolene for a long-term treatment (2–8 months of age). It was discovered that the pathological changes, including Aβ accumulation, negative synaptic plasticity and neuronal loss, in the hippocampal and cortical regions were rescued by dantrolene [33]. In their further study, the RyR expression in APPPS1 mice was inhibited by a genetic approach. The results implied that the blockade of RyR3 was beneficial for older AD neurons, while it would cause more synaptic and network dysfunction in young AD neurons [36]. The neuroprotective effects of up-regulation of RyR3 were also demonstrated in TgCRND8 mouse models of AD, where the authors reduced RyR3 expression using small interfering RNA [37].

Altogether, these studies and results reveal an inconsistent effect of RyR blockade treatment on AD. This may be due to the following reasons: 1) The different ages and durations dantrolene used and the different AD models examined. 2) There are three RyR isoforms: RyR1 (mainly in the skeletal muscle), [94] RyR2 (mainly in the myocardium) [95] and RyR3 (mainly in the brain) [96]. Both RyR1 and RyR3 are the targets of dantrolene in vivo, while RyR2 is unaffected by dantrolene [97]. However, till now, it’s not clear which isoform of RyR plays the main role AD: RyR2 alone, RyR3 alone or both. 3) It has been demonstrated that increased RyR expression and function are a compensation for AD pathology, which may be neuroprotective at the early stage of the disease. 4) A recent study demonstrated that dantrolene required magnesium (Mg) to arrest malignant hyperthermia [98]. It was demonstrated that RyR became effectively inhibited by dantrolene only when the cytoplasmicfree [Mg2+] (free [Mg2+]cyto) passed 1 mM, which means Ca2+ leak is unaffectable by dantrolene when [Mg2+]cyto is too low. Furthermore, it was found that a higher level of free [Mg2+] (1.5mM) was required to reduce halothane-induced Ca2+ influx through RyR by dantrolene, which means dantrolene is useless to reduce calcium leak at the resting level of free [Mg2+]cyto. The hypothesis that Mg2+ is required to make dantrolene administration effective reconciles previous contradictory reports in the therapeutic effects of dantrolene, where Mg2+ is present or absent, respectively [99]. Similarly, when dantrolene is used as a therapy for AD, targeting at RyR, is a certain [Mg2+]cyto required? Till now, there’s no related publication in the area of dantrolene therapy in AD.

CONCLUSION

Altered RyR expression levels and function have been discovered in AD patients, in MCI patients, and in several AD mouse models, both in vivo and in vitro. The results are not exactly consistent, which may be due to: 1) different AD models used 2) different stages of the AD pathogenesis. While it is widely accepted that increased expression and enhanced function of RyR1, RyR2 or RyR3 trigger the neurofibrillary pathology and amyloid deposition, some researchers propose that it may be a compensatory phenomenon that is neuroprotective. Enhanced ryanodine-mediated calcium release is demonstrated to be associated with the pathogenesis of AD disease. Furthermore, the perturbed calcium homeostasis is related to synaptic dysfunctions.

There are emerging evidence suggesting that RyR may contribute to the histopathological lesions of AD. The interplay of RyR, APP, PS, and Aβ has been wildly researched. The studies demonstrate that the mutations of APP and PS disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis via overexpression of RyR. Aβ accumulation also causes post-translational modifications of RyR. RyR remodeling in turn enhanced βAPP processing and Aβ production, leading to negative synaptic plasticity, neuron loss and cognitive deterioration.

The effects of dantrolene, the treatment aimed at RyR, turned out to be inconsistent. While most studies prove that blockade of RyR by dantrolene will rescue the disruption of Ca2+ signals and synaptic dysfunction, reduce Aβ accumulation, and prevent cognitive deficits, some researchers discovered converse effects. It may due to the different ways of administration, different treatment time, and different AD mouse models used. Also, the dual role of RyR in AD pathology is supposed to be taken into consideration. It is proposed that RyR may function as a protective responder at early stages of the disease and act as a pathogenic molecular determinant. Mg2+ may be required to make dantrolene administration effective. Further studies are warranted to clarify the causes of these variations and assist new drug development targeting RYR.

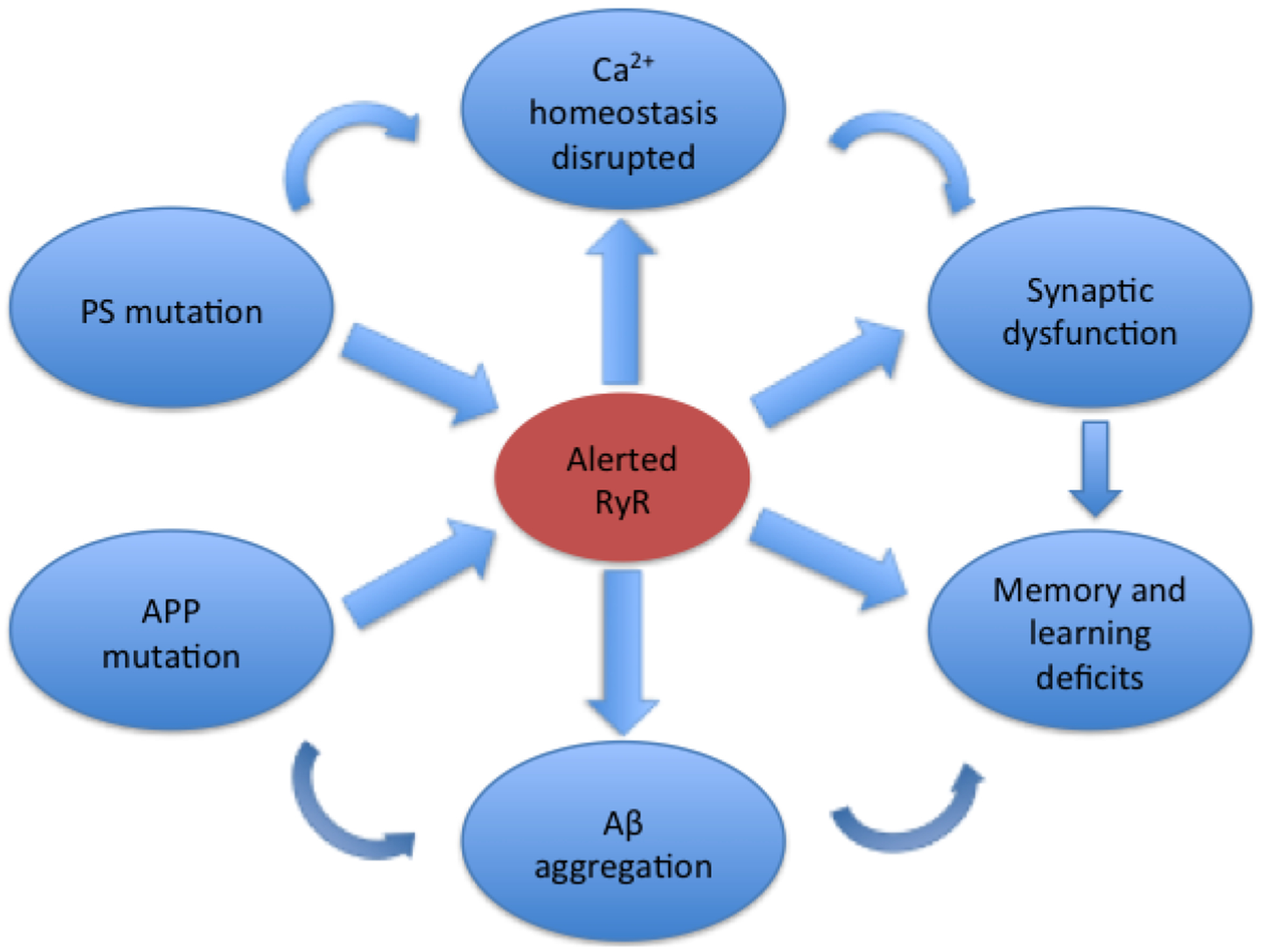

In conclusion, RyR has been revealed to play a vital role in AD pathology (Fig. 1). More studies are warranted to clarify how the altered RyR impacts the pathogenesis of AD. Dantrolene, aiming at ER-located RyR and maintaining the intracellular calcium homeostasis, with relatively tolerable side effects, could be a novel treatment for the disease, although the therapeutic efficacy has not been fully confirmed, especially in patients (Table 1).

Fig. (1).

The role of RyR in the AD pathology. The mutations of APP and PS disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis via overexpression of RyR. Aβ accumulation also causes post-translational modifications of RyR. RyR remodeling in turn enhanced βAPP processing and Aβ production, leading to neuronal death, synaptic structure and plasticity dysfunctions and learning and memory decline.

Table 1.

Dantrolene treatment in various AD models.

| AD Models | Study System | Treatment | AD Stage | Results | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ and Amyloid Plaque Production | Synaptic Dysfunction | Cell Death | Learning and Memory Deficits | |||||

| APPswe or overexpression of APP695 mutation | SH-SY5Y cells | dantrolene | reduced | [52] | ||||

| Tg2576 mice | Primary neurons | dantrolene | reduced | [52] | ||||

| APPPS1 mice | Hippocampal region | RyR3 KO | <3m | reduced | reduced | [38] | ||

| >6m | reduced | reduced | ||||||

| APPPS1 mice | Hippocampal and cortical region | dantrolene | 2–8m | reduced | reduced | reduced | [35] | |

| APPswe or overexpression of APP695 mutation | SH-SY5Y cells | dantrolene | reduced | [36] | ||||

| Tg2576 mice | Primary neurons | dantrolene | reduced | reduced | [36] | |||

| 3xTgAD mice | Whole brain | dantrolene | 2–13m | reduced | reduced | reduced | [56] | |

| PS1-m146V KI mice | Hippocampal neuron | dantrolene | 0–1d | reduced | [60] | |||

| Wistar rat | Primary emryos cortical neuron cultured with Aβ1–42 | dantrolene | reduced | [55] | ||||

| 3xTgAD mice | Hippocampal and cortical neurons | dantrolene | 2–3m | reduced | [59] | |||

| APPPS1 mice | Hippocampal and cortical neurons | dantrolene | 5–6m | reduced | [59] | |||

| 3xTgAD mice | Hippocampal region | dantrolene | 15–21m | reduced | [57] | |||

| 3xTgAD mice | Hippocampus region | dantrolene | 2–5m | Reduced | Reduced | [58] | ||

| TgCRND8 mice | Primary cortical neurons | Reduce RyR3 expression using small interfering RNA | reduced | [39] | ||||

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by grants to HW from the NIH (R01GM084979, 3R01GM084979-02S1, 2R01GM084979-06A1). We would like to thank Matan Y Ben Abou from Draxel University, Philadelphia, PA for editing of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- RyR

Ryanodine Receptor

- MH

Malignant Hyperthermia

- SR

Sarcoplasmic Reticulum

- ER

Endoplasmic Reticulum

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- FDA

Drug Administration

- MHAUS

Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States

- WHO

World Health Organization

- Aβ

Amyloid-β

- SAD

Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease

- FAD

Familial Alzheimer’s Disease

- APP

Amyloid Precursor Protein

- PS1

Presenilin 1

- PS2

Presenilin 2

- NFTs

Neurofibrillary Tangles

- MCI

Mild Cognitive Impairment

- IP3R

Inositol Trisphosphate Receptor

- CICR

Calcium-induced Calcium Release

- KI

Knock-in

- Mg

Magnesium

- Free [Mg2+]cyto

Cytoplasmic-free [Mg2+]

Footnotes

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The article is original, has been written by the stated authors who are all aware of its content and approve its submission, has not been published previously, it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, and the conflict is declared. If accepted, the article will not be published else-where in the same form, in any language, without the written consent of the publisher.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Huafeng Wei is a consultant of Eagle Pharmaceutical Company, New Jersey, USA.

REFERENCES

- [1].A. Alzheimer’s, 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 11, 332 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM, Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 362, 329–344 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thompson CA et al. , Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr 7, 18 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Guedel AE, Inhalation Anesthesia. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 52, 238 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brandom BW et al. , Ryanodine receptor type 1 gene variants in the malignant hyperthermia-susceptible population of the United States. Anesth. Analg 116, 1078 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kolb ME, Horne M, Martz R, Dantrolene in human malignant hyperthermia. Anesthesiology 56, 254–262 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Britt BA, Kalow W, Malignant hyperthermia: a statistical review. Canadian Anaesthetists’ Society Journal 17, 293–315 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Larach MG, Brandom BW, Allen GC, Gronert GA, Lehman EB, Cardiac Arrests and Deaths Associated with Malignant Hyperthermia in North America from 1987 to 2006A Report from The North American Malignant Hyperthermia Registry of the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 108, 603–611 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Inan S, Wei H, The cytoprotective effects of dantrolene: a ryanodine receptor antagonist. Anesth. Analg 111, 1400–1410 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Krause T, Gerbershagen M, Fiege M, Weisshorn R, Wappler F, Dantrolene–a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments. Anaesthesia 59, 364–373 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang H, Xu H, Thompson R, Zhang Y.-w., APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Brain 4, 3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tam JH, Pasternak SH, Amyloid and Alzheimer’s disease: inside and out. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 39, 286–298 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bukar Maina M, Al-Hilaly YK, Serpell LC, Nuclear tau and its potential role in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 6, 9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sherrington R et al. , Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 375, 754–760 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Levy-Lahad E et al. , Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer’s disease locus. Science 269, 973–977 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Drachman DA, The amyloid hypothesis, time to move on: Amyloid is the downstream result, not cause, of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 10, 372–380 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Folch J et al. , Current research therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Neural Plast 2016, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Lipp P, Calcium-a life and death signal. Nature 395, 645–648 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bezprozvanny I, Calcium signaling and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Mol. Med 15, 89–100 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P, Regulation of cell death: The calcium-apoptosis link. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 4, 552–565 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Khachaturian ZS, Introduction and Overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 568, 1–4 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pierrot N, Ghisdal P, Caumont AS, Octave JN, Intraneuronal amyloid-β1–42 production triggered by sustained increase of cytosolic calcium concentration induces neuronal death. J. Neurochem 88, 1140–1150 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pierrot N et al. , Calcium-mediated transient phosphorylation of tau and amyloid precursor protein followed by intraneuronal amyloid-β accumulation. J. Biol. Chem 281, 39907–39914 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lal R, Lin H, Quist AP, Amyloid beta ion channel: 3D structure and relevance to amyloid channel paradigm. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 1768, 1966–1975 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stutzmann GE, Calcium dysregulation, IP3 signaling, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscientist 11, 110–115 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Baloyannis SJ, Costa V, Michmizos D, Mitochondrial alterations Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias® 19, 89–93 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Johnson GV, Stoothoff WH, Tau phosphorylation in neuronal cell function and dysfunction. J. Cell Sci 117, 5721–5729 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Martin C, Chapman K, Seckl J, Ashley R, Partial cloning and differential expression of ryanodine receptor/calcium-release channel genes in human tissues including the hippocampus and cerebellum. Neuroscience 85, 205–216 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kelliher M et al. , Alterations in the ryanodine receptor calcium release channel correlate with Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary and β-amyloid pathologies. Neuroscience 92, 499–513 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bruno AM et al. , Altered ryanodine receptor expression in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging [EPub ahead of print], (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chakroborty S, Goussakov I, Miller MB, Stutzmann GE, Deviant ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium release resets synaptic homeostasis in presymptomatic 3xTg-AD mice. J. Neurosci 29, 9458–9470 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhang H, Sun S, Herreman A, De SB, Bezprozvanny I, Role of presenilins in neuronal calcium homeostasis. J. Neurosci 30, 85668580 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Oules B et al. , Ryanodine receptor blockade reduces amyloid-beta load and memory impairments in Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Neurosci 32, 11820–11834 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Supnet C, Grant J, Westaway D, Mayne M, Amyloid-β-(1–42) increases ryanodine receptor-3 expression and function in neurons of TgCRND8 mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry 281, 38440–38447 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu J et al. , The role of ryanodine receptor type 3 in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Channels 8, 230–242 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Supnet C, Noonan C, Richard K, Bradley J, Mayne M, Up-regulation of the type 3 ryanodine receptor is neuroprotective in the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem 112, 356–365 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wei H, Xie Z, Anesthesia, calcium homeostasis and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr.Alzheimer Res 6, 30–35 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Llinas R, Moreno H, Perspective on calcium and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 13, 196–197 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Stutzmann GE et al. , Enhanced Ryanodine-Mediated Calcium Release in Mutant PS1-Expressing Alzheimer’s Mouse Models. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1097, 265–277 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stutzmann GE et al. , Enhanced ryanodine receptor recruitment contributes to Ca2+ disruptions in young, adult, and aged Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neurosci 26, 5180–5189 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chan SL, Mayne M, Holden CP, Geiger JD, Mattson MP, Presenilin-1 mutations increase levels of ryanodine receptors and calcium release in PC12 cells and cortical neurons. J Biol.Chem 275, 18195–18200 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kipanyula MJ et al. , Ca2+ dysregulation in neurons from transgenic mice expressing mutant presenilin 2. Aging cell 11, 885–893 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ferreiro E, Oliveira CR, Pereira CM, The release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum induced by amyloid-beta and prion peptides activates the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Neurobiol. Dis 30, 331–342 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wu B, Yamaguchi H, Lai FA, Shen J, Presenilins regulate calcium homeostasis and presynaptic function via ryanodine receptors in hippocampal neurons. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 110, 15091–15096 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Goussakov I, Miller MB, Stutzmann GE, NMDA-mediated Ca2+ influx drives aberrant ryanodine receptor activation in dendrites of young Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neurosci 30, 12128–12137 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Makarewicz D, Zieminska E, Lazarewicz JW, Dantrolene inhibits NMDA-induced 45Ca uptake in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Neurochem. Int 43, 273–278 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Uhl GR, Snyder SH, Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coat protein neurotoxicity mediated by nitric oxide in primary cortical cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90, 3256–3259 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rybalchenko V, Hwang S-Y, Rybalchenko N, Koulen P, The cytosolic N-terminus of presenilin-1 potentiates mouse ryanodine receptor single channel activity. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 40, 84–97 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hayrapetyan V, Rybalchenko V, Rybalchenko N, Koulen P, The N-terminus of presenilin-2 increases single channel activity of brain ryanodine receptors through direct protein-protein interaction. Cell Calcium 44, 507–518 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Payne AJ et al. , Presenilins regulate the cellular activity of ryanodine receptors differentially through isotype-specific N-terminal cysteines. Exp. Neurol 250, 143–150 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Oulès B et al. , Leaky Ryanodine receptors increases Amyloid-beta load and induces memory impairments in Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Mol. Neurodegener 8, P54 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bussiere R et al. , Amyloid β production is regulated by β2-adrenergic signaling-mediated post-translational modifications of the ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem 292, 10153–10168 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ferreiro E, Oliveira CR, Pereira C, Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release through ryanodine and inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptors in the neurotoxic effects induced by the amyloid-β peptide. J. Neurosci. Res 76, 872–880 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Resende R, Ferreiro E, Pereira C, De Oliveira CR, Neurotoxic effect of oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptide 1–42: involvement of endoplasmic reticulum calcium release in oligomer-induced cell death. Neuroscience 155, 725–737 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kwon KJ et al. , Disruption of neuronal nitric oxide synthase dimerization contributes to the development of Alzheimer’s disease: Involvement of cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated phosphorylation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase at Ser293. Neurochem. Int 99, 52–61 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Welshhans K, Rehder V, Nitric oxide regulates growth cone filopodial dynamics via ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium release. Eur. J. Neurosci 26, 1537–1547 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Mikami Y et al. , Nitric oxide-induced activation of the type 1 ryanodine receptor is critical for epileptic seizure-induced neuronal cell death. EBioMedicine 11, 253–261 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kakizawa S et al. , Nitric oxide-induced calcium release via ryanodine receptors regulates neuronal function. The EMBO journal 31, 417–428 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Nathan C et al. , Protection from Alzheimer’s-like disease in the mouse by genetic ablation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Exp. Med 202, 1163–1169 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Takahashi M et al. , Prolonged nitric oxide treatment induces tau aggregation in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett 510, 48–52 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ditlevsen DK, Køhler LB, Berezin V, Bock E, Cyclic guanosine monophosphate signalling pathway plays a role in neural cell adhesion molecule-mediated neurite outgrowth and survival. J. Neurosci. Res 85, 703–711 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kohgami S, Ogata T, Morino T, Yamamoto H, Schubert P, Pharmacological shift of the ambiguous nitric oxide action from neurotoxicity to cyclic GMP-mediated protection. Neurol. Res 32, 938–944 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Colton C et al. , NO synthase 2 (NOS2) deletion promotes multiple pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 12867–12872 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Colton CA et al. , The effects of NOS2 gene deletion on mice expressing mutated human AβPP. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 15, 571–587 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chakroborty S, Kim J, Schneider C, West AR, Stutzmann GE, Nitric oxide signaling is recruited as a compensatory mechanism for sustaining synaptic plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neurosci 35, 6893–6902 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Rivest S, TREM2 enables amyloid β clearance by microglia. Cell Res 25, 535 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wisniewski H, Wegiel J, Wang K, Lach B, Ultrastructural studies of the cells forming amyloid in the cortical vessel wall in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 84, 117–127 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Rajendran L, Paolicelli RC, Microglia-Mediated Synapse Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci 38, 2911–2919 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Griffith CM et al. , Aberrant expression of the pore-forming KATP channel subunit Kir6. 2 in hippocampal reactive astrocytes in the 3xTg-AD mouse model and human Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 336, 81–101 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Yamamoto M et al. , Interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α regulate amyloid-β plaque deposition and β -secretase expression in Swedish mutant APP transgenic mice. The American journal of pathology 170, 680–692 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Blasko I et al. , Costimulatory effects of interferon-γ and interleukin-1β or tumor necrosis factor α on the synthesis of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 by human astrocytes. Neurobiol. Dis 7, 682–689 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].DeWitt DA, Perry G, Cohen M, Doller C, Silver J, Astrocytes regulate microglial phagocytosis of senile plaque cores of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol 149, 329–340 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Howlett D et al. , Characterisation of amyloid-induced inflammatory responses in the rat retina. Exp. Brain Res 214, 185 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Jamalidoust M et al. , Construction of AAV-rat-IL4 and Evaluation of its Modulating Effect on Aβ (1–42)-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokines in Primary Microglia and the B92 Cell Line by Quantitative PCR Assay. Jundishapur journal of microbiology 9, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Stenovec M et al. , Expression of familial Alzheimer disease presenilin 1 gene attenuates vesicle traffic and reduces peptide secretion in cultured astrocytes devoid of pathologic tissue environment. Glia 64, 317–329 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Oksanen M et al. , PSEN1 Mutant iPSC-Derived Model Reveals Severe Astrocyte Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Stem cell reports 9, 1885–1897 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hopp SC et al. , Differential neuroprotective and antiinflammatory effects of L-type voltage dependent calcium channel and ryanodine receptor antagonists in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol 10, 35–44 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Hopp S et al. , 129. Blockade of L-type voltage dependent calcium channels or ryanodine receptors during chronic neuroinflammation improves spatial memory and reduces expression of inflammatory markers. Brain, Behav., Immun 40, e38 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- [79].Perkins G et al. , Electron tomography of neuronal mitochondria: three-dimensional structure and organization of cristae and membrane contacts. J. Struct. Biol 119, 260–272 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Csordás G et al. , Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol. Cell 39, 121–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].García-Pérez C, Hajnóczky G, Csordás G, Physical coupling supports the local Ca2+ transfer between sarcoplasmic reticulum subdomains and the mitochondria in heart muscle. J. Biol. Chem 283, 32771–32780 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kopach O, Kruglikov I, Pivneva T, Voitenko N, Fedirko N, Functional coupling between ryanodine receptors, mitochondria and Ca2+ ATPases in rat submandibular acinar cells. Cell Calcium 43, 469–481 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Jakob R et al. , Molecular and functional identification of a mitochondrial ryanodine receptor in neurons. Neurosci. Lett 575, 7–12 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Gibson GE, Thakkar A, Interactions of mitochondria/metabolism and calcium regulation in Alzheimer’s disease: a calcinist point of view. Neurochem. Res 42, 1636–1648 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Area-Gomez E et al. , Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. The EMBO journal 31, 4106–4123 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Contino S et al. , Presenilin 2-Dependent Maintenance of Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacity and Morphology. Front. Physiol 8, 796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Pavlov PF et al. , Mitochondrial γ-secretase participates in the metabolism of mitochondria-associated amyloid precursor protein. The FASEB Journal 25, 78–88 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Peng J et al. , Early and chronic treatment with dantrolene blocked later learning and memory deficits in older Alzheimer’s triple transgenic mice. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 7, e67 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [89].Wu Z et al. , Long-term Dantrolene Treatment Reduced Intraneuronal Amyloid in Aged Alzheimer Triple Transgenic Mice. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord 29, 184–191 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Peng J et al. , Dantrolene ameliorates cognitive decline and neuropathology in Alzheimer triple transgenic mice. Neuroscience letters 516, 274–279 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Chakroborty S et al. , Stabilizing ER Ca(2+) Channel Function as an Early Preventative Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS.One 7, e52056 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Zhang H et al. , Calcium signaling, excitability, and synaptic plasticity defects in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J.Alzheimers.Dis 45, 561–580 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Takeshima H et al. , Primary structure and expression from complementary DNA of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Nature 339, 439 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Rossi D, Sorrentino V, Molecular genetics of ryanodine receptors Ca2+-release channels. Cell Calcium 32, 307–319 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL, Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2, a003996 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Zhao F, Li P, Chen SW, Louis CF, Fruen BR, Dantrolene inhibition of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels molecular mechanism and isoform selectivity. J. Biol. Chem 276, 13810–13816 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Choi RH, Koenig X, Launikonis BS, Dantrolene requires Mg2+ to arrest malignant hyperthermia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 4811–4815 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Cannon SC, Mind the magnesium, in dantrolene suppression of malignant hyperthermia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 4576–4578 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]