Abstract

Aims

The Covid‐19 pandemic affects care for cardiovascular conditions, but data on heart failure (HF) are scarce. This study aims to analyse HF care and in‐hospital outcomes during the pandemic in Germany.

Methods and results

A total of 9452 HF admissions were studied using claims data of 65 Helios hospitals; 1979 in the study period (13 March 30 April 2020) and 4691 and 2782 in two control periods (13 March to 30 April 2019 and 1 January to 12 March 2020). HF admissions declined compared with both control periods by 29–38%. Cardiac resynchronization therapy was implanted in 0.55% during the study period, 0.32% [odds ratio (OR) 1.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68–4.04, P = 0.27] in the previous year and 0.43% (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.64–2.84, P = 0.43) in the same year control. Intensive care treatment was 6.22% during the study period, 4.49% in the previous year (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.13–1.89, P < 0.01), and 5.27% in the same year control (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.96–1.49, P = 0.12). Length of hospital stay was 7.0 ± 5.0 days in the study and 7.8 ± 5.6 (P < 0.01) and 7.3 ± 5.1 days (P = 0.07) in the control periods. In‐hospital mortality was 7.0% in the study and 5.5% in both control periods (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

During the early phase of the Covid‐19 pandemic in Germany, HF treatment pathways seem not to be affected, but hospital stay shortened and in‐hospital mortality increased. As the pandemic continues, this early signal demands close monitoring and further investigation of potential causes.

Keywords: Heart failure, In‐hospital mortality, Covid‐19

The Covid‐19 pandemic affects also medical care for cardiovascular conditions. For instance, a reduction of hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 with a parallel increase in fatality and complication rates 4 has been observed during the pandemic. Very recently, a small single‐centre US study in heart failure (HF) patients also showed a decrease in acute HF admissions. 5 The authors suggested ‘analyses of international heart failure registries would facilitate comparisons of national and regional hospital admission trends. Understanding the extent of reduced AHF hospitalization rates will be critical for the care of patients with HF in the Covid‐19 era’. 5 By following up on this, this research letter aims to provide an up‐to‐date overview of emergency admissions for HF cases during the pandemic in Germany.

We performed a retrospective analysis of claims data of 65 hospitals in Germany serving about 10% of the German population. 6 Consecutive completed cases with an emergency hospital admission for HF between 13 March and 30 April 2020 (study period; protection stage according to the German pandemic plan), 13 March and 30 April 2019 (previous year control), and 1 January and 12 March 2020 (same year control) were studied. Hospitalizations were selected on the basis of primary diagnosis according to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD‐10‐GM (German Modification)] codes (I42.x; I43.x; I50.x). Patients (n = 15) with concomitant Covid‐19 were excluded. Implantation of devices for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT; 5‐377.4, 5‐377.7) and intensive care treatment (8‐980, 8‐98f) were defined according to the German procedure classification (‘Operationen und Prozedurenschlüssel’). Charlson co‐morbidity index (CCI) was calculated as described previously. 6

Data were stored in a pseudonomymized form, and data use was approved by the Helios hospitals' data protection authority.

Incidence rates for HF admissions were calculated by dividing the number of cumulative admissions by the number of days for each time period. Incidence rate ratios comparing the study period with both control periods were calculated using Poisson generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) to model the number of hospitalizations per day. Inferential statistics analysing age, sex, HF aetiology, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, CCI, and hospital volume were based on GLMMs specifying hospitals as random factor. For the comparison of selected therapies (CRT implants and intensive care) and univariable and multivariable analyses of in‐hospital mortality, logistic GLMMs and for length of stay linear GLMM were used. A subset of cases (5.7%, n = 541) was unclassified with respect to NYHA. Multivariate imputation by chained equations (Mice) was used for imputations of missing data and was based on age, sex, HF aetiology, and CCI. We used logistic regression with bootstrap and 10 iterations.

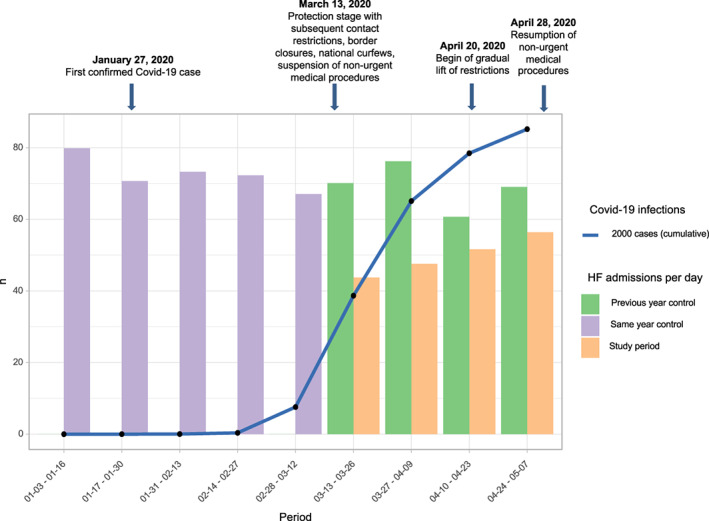

A total of 9452 HF admissions were studied; 1979 in the study period and 4691 and 2782 in the two control periods. HF admissions declined in the study compared with both control periods, which was consistent across age, sex, NYHA class, HF aetiology, co‐morbidities, and hospital volume (Table 1). These declines corresponded with key Covid‐19‐related events, national and state guidance, and with a rise in cumulative confirmed cases of Covid‐19 in Germany. As of 30 April 2020, there were 159 119 confirmed cases and 6288 deaths attributed to Covid‐19 (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Hospital admissions per day (cumulative admissions/days in period) and incidence rate ratios in relevant patient groups

| Admissions per day | Same year control | Previous year control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Study period | Same year control | Previous year control | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) P Value | P for interaction | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | P for interaction |

| Total | 40.4 | 65.2 | 56.8 |

0.62 (0.59–0.65) <0.01 |

— |

0.71 (0.67–0.76) <0.01 |

— |

| Age | |||||||

| ≤64 years | 4.5 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 0.63 (0.54–0.74) | 0.68 (0.58–0.81) | ||

| 65–74 years | 6.3 | 10.6 | 9.3 | 0.60 (0.52–0.68) | 0.58 | 0.68 (0.59–0.78) | 0.95 |

| ≥75 years | 29.8 | 47.4 | 40.8 | 0.63 (0.59–0.67) | 0.95 | 0.73 (0.68–0.78) | 0.48 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 19.6 | 31.2 | 26.4 | 0.63 (0.58–0.68) | 0.74 (0.68–0.80) | ||

| Female | 20.8 | 34.0 | 30.3 | 0.61 (0.57–0.66) | 0.61 | 0.69 (0.63–0.75) | 0.19 |

| HF aetiology | |||||||

| Ischaemic | 15.7 | 24.6 | 22.4 | 0.64 (0.58–0.69) | 0.70 (0.64–0.77) | ||

| Non‐ischaemic | 24.7 | 40.5 | 34.4 | 0.61 (0.57–0.65) | 0.45 | 0.72 (0.67–0.77) | 0.62 |

| NYHA class a | |||||||

| NYHA class I/II | 2.9 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 0.57 (0.47–0.69) | 0.55 (0.45–0.67) | ||

| NYHA class III/IV | 35.2 | 56.3 | 48.0 | 0.63 (0.59–0.66) | 0.33 | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | <0.01 |

| NYHA class b | |||||||

| NYHA class I/II | 3.1 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 0.56 (0.47–0.68) | 0.54 (0.44–0.65) | ||

| NYHA class III/IV | 37.3 | 59.7 | 51.0 | 0.63 (0.59–0.66) | 0.30 | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | <0.01 |

| Charlson co‐morbidity index | |||||||

| <4 | 20.9 | 36.2 | 30.8 | 0.58 (0.54–0.62) | 0.68 (0.63–0.73) | ||

| ≥4 | 19.4 | 29.0 | 25.9 | 0.67 (0.62–0.72) | <0.01 | 0.75 (0.69–0.82) | 0.09 |

| Hospital volume c | |||||||

| Low | 4.6 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 0.63 (0.54–0.74) | 0.60 (0.51–0.71) | ||

| Intermediate | 12.7 | 21.9 | 19.2 | 0.58 (0.53–0.63) | 0.34 | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) | 0.36 |

| High | 23.1 | 36.0 | 29.9 | 0.64 (0.60–0.69) | 0.83 | 0.77 (0.72–0.84) | <0.01 |

541 cases with missing NYHA class.

With imputation of missing NYHA class data.

Based on tertiles of average admissions in same year control period, i.e. low <48, intermediate 48–90, and high volume >90 admissions.

Figure 1.

Emergency heart failure hospitalizations at Helios hospitals, Covid‐19 cases, and key public health measures in Germany.

CRT was implanted in 0.55% during the study period, which was numerically higher but statistically not different to 0.32% [odds ratio (OR) 1.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68–4.04, P = 0.27] in the previous year and 0.43% (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.64–2.84, P = 0.43) in the same year control. Intensive care treatment was 6.22% during the study period, 4.49% in the previous year (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.13–1.89, P < 0.01), and 5.27% in the same year control (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.96–1.49, P = 0.12).

Length of hospital stay was 7.0 ± 5.0 days in the study and 7.8 ± 5.6 (P < 0.01) and 7.3 ± 5.1 days (P = 0.07) in the control periods.

In‐hospital mortality was 7.0% in the study and 5.5% in both control periods. With the use of univariable and multivariable analyses, several clinical characteristics and Covid‐19 study period were associated with in‐hospital mortality (Table 2 and Table S1 with imputation of missing NYHA class).

Table 2.

In‐hospital mortality rates, univariable and multivariable analyses

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Proportion (n/N) | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age | |||||

| ≤64 years | 2.2% (23/1057) | ||||

| 65–74 years | 2.5% (39/1532) | 1.18 (0.70–1.98) | 0.54 | 1.12 (0.65–1.92) | 0.69 |

| ≥75 years | 7.1% (490/6863) | 3.46 (2.27–5.28) | <0.01 | 3.09 (1.97–4.83) | <0.01 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 5.5% (246/4500) | ||||

| Female | 6.2% (306/4952) | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 0.14 | 0.96 (0.79–1.15) | 0.65 |

| HF aetiology | |||||

| Ischaemic | 5.4% (196/3637) | ||||

| Non‐ischaemic | 6.1% (356/5815) | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | 0.15 | 1.20 (0.99–1.45) | 0.07 |

| NYHA class a | |||||

| NYHA class I/II | 0.8% (6/780) | ||||

| NYHA class III/IV | 6.3% (516/8131) | 8.97 (4.00–20.11) | <0.01 | 7.66 (3.41–17.24) | <0.01 |

| Charlson co‐morbidity index | |||||

| <4 | 5.1% (264/5141) | ||||

| 4 | 6.7% (288/4311) | 1.33 (1.12–1.58) | <0.01 | 1.21 (1.01–1.45) | 0.04 |

| Hospital volume | |||||

| Low | 6.7% (75/1127) | ||||

| Intermediate | 6.2% (196/3137) | 0.93 (0.69–1.26) | 0.64 | 0.96 (0.70–1.32) | 0.82 |

| High | 5.4% (281/5188) | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) | 0.13 | 0.79 (0.59–1.08) | 0.14 |

| Period | |||||

| Study period | 7.0% (138/1979) | ||||

| Same year control | 5.5% (260/4691) | 0.78 (0.63–0.97) | 0.02 | 0.79 (0.64–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Previous year control | 5.5% (154/2782) | 0.78 (0.61–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.80 (0.63–1.03) | 0.08 |

For the inclusion of variables into a multivariable analysis of in‐hospital mortality, we defined P value < 0.15 as a criterion. All factors met the criterion and were hence used in a multivariable logistic GLMM.

541 cases with missing NYHA class. In‐hospital mortality analysis using imputed NYHA class can be found in Table S1.

To the best of our knowledge, this report is the largest sample of emergency HF hospitalizations showing a significant decrease in the German Helios hospital network during the Covid‐19 pandemic. While treatment pathways seem not to be affected, hospital stay shortened and in‐hospital mortality increased by ~20%.

Reduction in HF hospitalizations is in agreement with more recent studies in different countries and settings (Table S2). 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Fear of contagion at the hospital and deferral of less severe cases may explain reduced hospitalizations. Our study extends those findings by showing a consistent reduction across several key patient groups.

In addition, length of stay was reduced during the pandemic, which is similar to one US study in acute cardiovascular conditions including 40.8% HF cases. 10 It can be speculated that early discharge is enforced to reduce Covid‐19 exposure in health care settings. In addition, suspension of non‐urgent medical procedures may reduce wait times for certain necessary procedures.

While there are only few data on in‐hospital mortality showing inconsistent results (Table S2 ), none of those studies have analysed potential associations with mortality. We have found several clinical characteristics and the Covid‐19 study period to associate with hospital mortality, but other important predictors linked with case severity such as laboratory values or ejection fraction 11 cannot be investigated using claims data. Therefore, analysis of possible differential effects in HF with reduced and preserved ejection fraction is not possible. Although we have excluded confirmed Covid‐19 cases from this analysis, we cannot rule out undetected Covid‐19 cases as additional contributor to increased mortality.

As the pandemic continues, this early signal demands close monitoring and further investigation of potential causes.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Table S1. In‐hospital mortality rates, uni‐ and multivariable analysis (using imputation for missing NYHA data).

Table S2. Literature review of heart failure care during Covid‐19 pandemic.

Bollmann, A. , Hohenstein, S. , König, S. , Meier‐Hellmann, A. , Kuhlen, R. , and Hindricks, G. (2020) In‐hospital mortality in heart failure in Germany during the Covid‐19 pandemic. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 4416–4419. 10.1002/ehf2.13011.

References

- 1. De Filippo O, D'Ascenzo F, Angelini F, Bocchino PP, Conrotto F, Saglietto A, Secco GG, Campo G, Gallone G, Verardi R, Gaido L, Iannaccone M, Galvani M, Ugo F, Barbero U, Infantino V, Olivotti L, Mennuni M, Gili S, Infusino F, Vercellino M, Zucchetti O, Casella G, Giammaria M, Boccuzzi G, Tolomeo P, Doronzo B, Senatore G, Marra WG, Rognoni A, Trabattoni D, Franchin L, Borin A, Bruno F, Galluzzo A, Gambino A, Nicolino A, Giachet AT, Sardella G, Fedele F, Monticone S, Montefusco A, Omede P, Pennone M, Patti G, Mancone M, De Ferrari GM. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during Covid‐19 outbreak in northern Italy. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 88–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, Dixon S, Rade JJ, Tannenbaum M, Chambers J, Huang PP, Henry TD. Reduction in ST‐segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 75: 2871–2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, Bauer A, Reinstadler SJ. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID‐19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 1852–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Rosa S, Spaccarotella C, Basso C. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID‐19 era. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 2083–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cox ZL, Lai P, Lindenfeld J. Decreases in acute heart failure hospitalizations during COVID‐19. Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22: 1045–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. König S, Ueberham L, Schuler E, Wiedemann M, Reithmann C, Seyfarth M, Sause A, Tebbenjohanns J, Schade A, Shin DI, Staudt A, Zacharzowsky U, Andrié R, Wetzel U, Neuser H, Wunderlich C, Kuhlen R, Tijssen JGP, Hindricks G, Bollmann A. In‐hospital mortality of patients with atrial arrhythmias: insights from the German‐wide Helios hospital network of 161 502 patients and 34 025 arrhythmia‐related procedures. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 3947–3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall ME, Vaduganathan M, Khan MS, Papadimitriou L, Long RC, Hernandez GA, Moore CK, Lennep BW, Mcmullan MR, Butler J. Reductions in heart failure hospitalizations during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Card Fail 2020; 26: 462–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colivicchi F, Di Fusco SA, Magnanti M, Cipriani M, Imperoli G. The impact of the coronavirus disease‐2019 pandemic and Italian lockdown measures on clinical presentation and management of acute heart failure. J Card Fail 2020; 26: 464–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersson C, Gerds T, Fosbøl E, Phelps M, Andersen J, Lamberts M, Holt A, Butt JH, Madelaire C, Gislason G, Torp‐Pedersen C, Køber L, Schou M. Incidence of new‐onset and worsening heart failure before and after the COVID‐19 epidemic lockdown in Denmark: a nationwide cohort study. Circ Heart Fail 2020; 13: e007274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhatt AS, Moscone A, McElrath EE, Varshney AS, Claggett BL, Bhatt DL, Butler J, Adler DA, Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M. Declines in hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a multicenter tertiary care experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB, OPTIMIZE‐HF Investigators and Coordinators . Predictors of in‐hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure: insights from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE‐HF). J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. In‐hospital mortality rates, uni‐ and multivariable analysis (using imputation for missing NYHA data).

Table S2. Literature review of heart failure care during Covid‐19 pandemic.