Abstract

Aims

Sacubitril‐valsartan has been shown to have superior effects over angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with heart failure (HF) and hypertension. The efficacy and safety of sacubitril‐valsartan in patients with HF are controversial. We performed a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials to assess and compare the effect and adverse events of sacubitril‐valsartan, valsartan, and enalapril in patients with HF.

Methods and results

We conducted a systematic search using PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Randomized controlled trials involving the use of sacubitril‐valsartan in patients with HF were included. We assessed the pooled odds ratio (OR) of all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and hospitalization for HF in fixed‐effects models and the pooled risk ratio (RR) of symptomatic hypotension, worsening renal function, and hyperkalaemia in fixed‐effects models. Of the 315 identified records, six studies involving 14 959 patients were eligible for inclusion. Sacubitril‐valsartan reduced the endpoints of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in three trials with pooled ORs of 0.83 (P = 0.0006) and 0.78 (P < 0.0001), respectively. Regarding the composite outcome of hospitalization for HF in five trials, the pooled OR was 0.79 (P < 0.00001). Compared with enalapril or valsartan, sacubitril‐valsartan was associated with a high risk of symptomatic hypotension (RR 1.47, P < 0.00001), low risk of worsening renal function (RR 0.81, P = 0.005), and low rate of serious hyperkalaemia (≥6.0 mmol/L) (RR 0.76, P = 0.0007) in all six trials.

Conclusions

Compared with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, sacubitril‐valsartan significantly decreased the risk of death from all causes or cardiovascular causes in HFrEF and hospitalization for HF in both patients with HFrEF and HF with preserved ejection fraction. Sacubitril‐valsartan reduced the risk of renal dysfunction and serious hyperkalaemia but was associated with more symptomatic hypotension.

Keywords: Heart failure, Sacubitril‐valsartan, Meta‐analysis

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood. 1 HF affects more than 23 million people worldwide. 2 Approximately 50% of people diagnosed with HF die within 5 years, 1 , 3 and HF has become the most frequent reason for hospitalization and rehospitalization among elderly people. 1 , 4 Despite the use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), β‐blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, 5 which can partially attenuate left ventricular (LV) dilation and remodelling in HF, the morbidity and mortality of patients remain unacceptably high. 6

Sacubitril‐valsartan is a first‐in‐class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor that has been used in both HF and hypertension. This neprilysin inhibitor has vasodilating effects and facilitates sodium excretion, 7 and when combined with the inhibition of the renin‐angiotensin system, it has superior effects over ACE inhibitors or ARBs alone. 8 , 9 In the PARADIGM‐HF trial, sacubitril‐valsartan significantly reduced the pooled endpoints of all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization for HF compared with enalapril for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). 10 , 11 However, several studies have shown that sacubitril‐valsartan did not result in significantly lower rates of rehospitalization for HF, 9 , 12 , 13 death from cardiovascular causes, 12 , 13 , 14 and death from all causes, 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 especially in HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Although the risk of serious angioedema from neprilysin inhibition has been minimized, major adverse events, including hypotension, worsening renal function, and hyperkalaemia, have been shown to be heterogeneous in different randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

In the current paper, we performed a meta‐analysis to analyse the comprehensive outcomes of RCTs of HF in which sacubitril‐valsartan was compared with renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system (RAS) inhibitors alone.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

We conducted a systematic search using PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to 21 November 2019. We searched for studies with medical subject heading terms and text, including ‘Heart Failure’ or ‘Cardiac Failure’ or ‘Heart Decompensation’ or ‘Decompensation, Heart’ or ‘Heart Failure, Right‐Sided’ or ‘Heart Failure, Right Sided’ or ‘Right‐Sided Heart Failure’ or ‘Right Sided Heart Failure’ or ‘Myocardial Failure’ or ‘Congestive Heart Failure’ or ‘Heart Failure, Congestive’ or ‘Heart Failure, Left‐Sided’ or ‘Heart Failure, Left Sided’ or ‘Left‐Sided Heart Failure’ or ‘Left Sided Heart Failure’ and ‘LCZ 696’ or ‘LCZ696’ or ‘LCZ‐696’ or ‘sacubitril’ or ‘sacubitril‐valsartan’ or ‘entresto’. We searched for RCTs using the search filters from McMaster University. We also searched the corresponding references of each retrieved study. This meta‐analysis was conducted and performed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 15

Selection criteria

The efficacy and safety outcomes of sacubitril‐valsartan were compared with those of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in all RCTs. The following inclusion criteria were used: (i) RCTs with a sacubitril‐valsartan (Sac/Val) group and a control group; (ii) RCTs including chronic or haemodynamically stable patients with acute HF; and (iii) RCTs analysing primary efficacy outcomes, including death from cardiovascular causes, death from any cause, hospitalization for HF, and key adverse events, including symptomatic hypotension, worsening renal function, hyperkalaemia, and angioedema. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) duplicated papers related to the same trial; (ii) studies, such as systemic reviews, comments, case reports, conference abstracts, editorials, observational cohort studies, and real‐world studies; and (iii) incomplete RCTs or RCTs failing to report the outcomes of interest.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data extraction and quality assessments of the studies were performed independently by two reviewers. The data included the baseline characteristics of the trials, interventions, comparisons, sample size, medication, and follow‐up duration. The outcomes included death from any cause, death from cardiovascular causes, hospitalization for HF, symptomatic hypotension, renal dysfunction, hyperkalaemia, serious hyperkalaemia, and angioedema. The two reviewers cross‐checked the data. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion or referral to a third author (W. Q. H.).

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of the six included RCTs was assessed by using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (Review Manager 5.3), which included the following sections: selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other biases.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed by using Review Manager Version 5.3.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The efficacy and safety outcomes were measured as dichotomous outcome variables and compared between the sacubitril‐valsartan group and the control group. The pooled odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were collected in the comparative analyses. We assessed heterogeneity by using the I 2 test and Cochran's χ 2 test. The total variation in the studies was described by the I 2 statistic, which reflected heterogeneity. An I 2 ≥ 50% or a corresponding P < 0.10 indicated significant heterogeneity among the different studies. When I 2 < 50% and P > 0.10, we report the results of fixed‐effects models as sensitivity analyses. All P‐values were two‐tailed, with statistical significance specified at 0.05 and confidence intervals (CIs) reported at the 95% level. When I 2 > 45%, a sensitivity analysis was further performed by sequentially deleting each study and reanalysing the datasets of all remaining studies.

Results

Description of the study selection process and study characteristics

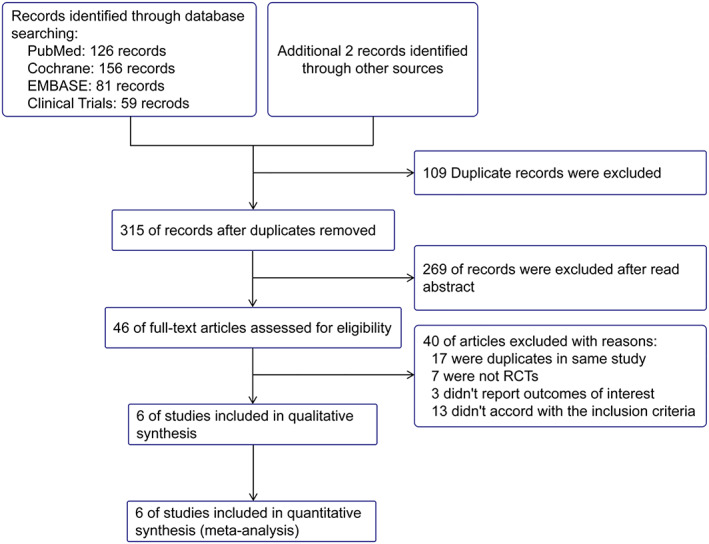

The flow diagram of study selection is shown in Figure 1 . The initial search identified 315 records after removing duplicate records. The full texts of 46 articles were reviewed in detail, and 40 articles were further excluded because the papers were related to the same trials (n = 17), did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 13), did not include real RCTs (n = 7), or had no outcomes of interest (n = 3). Finally, six double‐blind RCTs with 14 959 participants were included in our meta‐analysis. 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 16

FIGURE 1.

Study search diagram adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement. RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

Supporting Information, Table S1 shows the baseline characteristics of the included studies. All studies reported primary efficacy outcomes or key adverse events, including cardiovascular mortality, all‐cause mortality, hospitalization for HF, symptomatic hypotension, worsening renal function, hyperkalaemia and serious hyperkalaemia, and angioedema. The sample sizes of the trials ranged from 118 to 8399 patients, and the follow‐up durations ranged from 8 weeks to 35 months. The risk of bias was assessed in the six studies and generally found to be low in each study (Supporting Information, Figure S1 ).

Primary efficacy outcomes

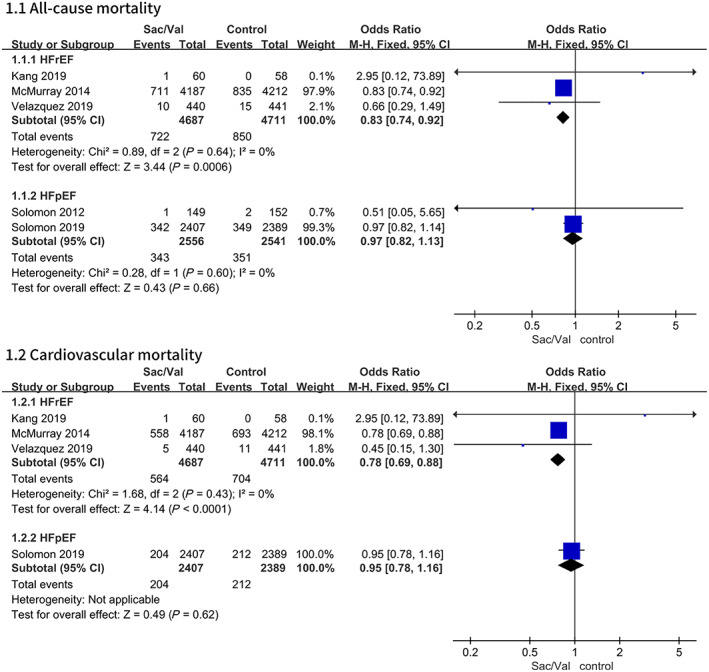

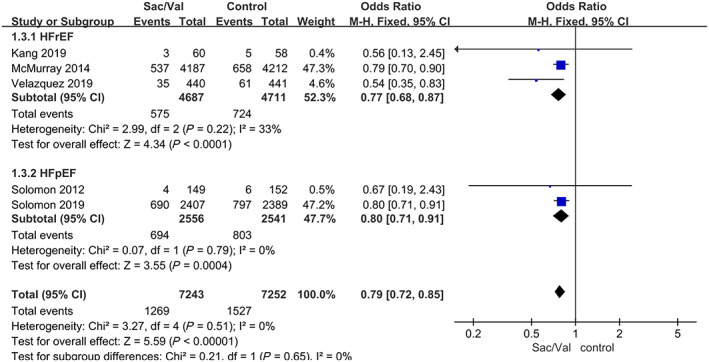

To assess the primary outcome, five trials were included in the meta‐analysis. The estimated results of the primary efficacy outcomes of death from all causes, deaths from cardiovascular causes and hospitalization for HF are presented in Figures 2 and 3 .

FIGURE 2.

Data of the comparative analysis for the effective outcomes of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in different patients with HF. HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; Sac/Val, sacubitril‐valsartan.

FIGURE 3.

Data of the comparative analysis for the effective outcomes of hospitalization for heart failure. Hospitalization for heart failure was defined as the first hospitalization for worsening heart failure in the PARADIGM‐HF, PARAMOUNT‐HF, PIONEER‐HF, and PRIME studies but not the PARAGON‐HF study, which included the first hospitalization and hospitalizations for recurrent events. HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; Sac/Val, sacubitril‐valsartan.

The composite risks of death from all causes and cardiovascular diseases were numerically lower in the patients with HFrEF receiving sacubitril‐valsartan. Regarding the outcome of all‐cause mortality, the pooled OR based on three studies 11 , 12 , 14 was 0.83, 95% CI 0.74–0.92, P = 0.0006 (P = 0.64 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%). The OR of cardiovascular mortality based on three studies was 0.78, 95% CI 0.69–0.88, P < 0.0001 (P = 0.43 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%). There were no significant differences in all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality between the sacubitril‐valsartan group and the control group among the patients with HFpEF 9 , 13 (Figure 2 ).

Compared with enalapril or valsartan, sacubitril‐valsartan reduced the composite risk of hospitalization for HF by 21% based on five studies, 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 and the pooled OR was 0.79, 95% CI 0.72–0.85, P < 0.00001 (P = 0.51 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%). The subgroup analyses showed that the use of sacubitril‐valsartan had a similar benefit in reducing the composite risk of hospitalization for HF in patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF (Figure 3 ).

Adverse events of interest

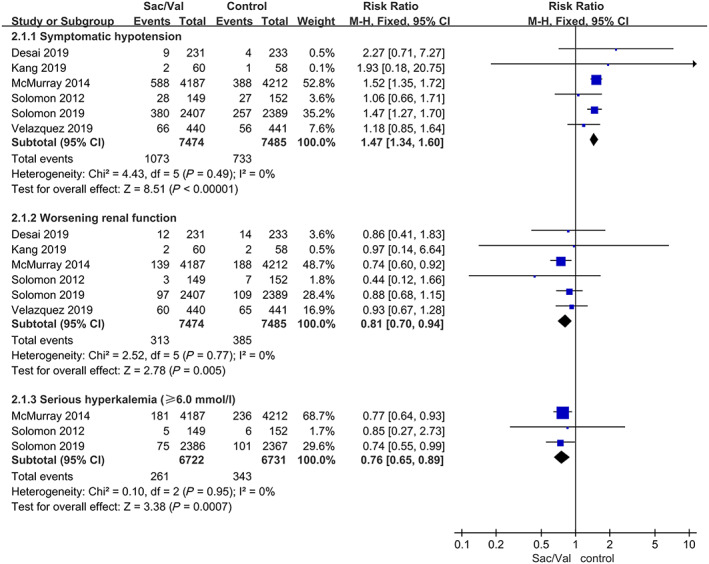

Symptomatic hypotension

Regarding this adverse event, compared with enalapril or valsartan, sacubitril‐valsartan led to a numerically higher risk of symptomatic hypotension in all six trials with a pooled RR of 1.47, 95% CI 1.34–1.60, P < 0.00001 (P = 0.49 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%) (Figure 4 ). We obtained the same results in subgroup analyses of different control groups (Supporting Information, Figure S2 ).

FIGURE 4.

Data of the comparative analysis for the safety outcomes of symptomatic hypotension, worsening renal function, and serious hyperkalaemia (≥6.0 mmol/L). Worsening renal function was defined as a decrease in eGFR ≥35% or an increase in serum creatinine ≥0.5 mg/dL from baseline AND a decrease in eGFR ≥25% from baseline or serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL. Sac/Val, sacubitril‐valsartan.

Worsening renal function

The patients treated with sacubitril‐valsartan were associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of worsening renal function with a pooled RR of 0.81, 95% CI 0.70–0.94, P = 0.005 (P = 0.77 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%) (Figure 4 ). We revised the results by performing subgroup analyses of the different control groups, and the composite outcome of worsening renal function in the sacubitril‐valsartan group was lower than that in the enalapril group 11 , 14 , 16 with a pooled RR of 0.79, 95% CI 0.67–0.95, P = 0.010 (P = 0.53 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%) (Supporting Information, Figure S3 ). There was no significant difference between the sacubitril‐valsartan group and the valsartan group. 9 , 12 , 13

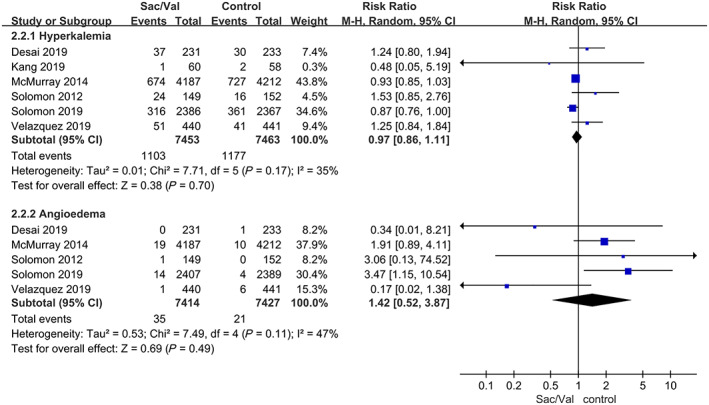

Hyperkalaemia

Regarding the adverse event of hyperkalaemia, the composite outcome did not significantly differ between the sacubitril‐valsartan group and the control group in all six trials with a pooled RR of 0.97, 95% CI 0.86–1.11, P = 0.70 (P = 0.17 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 36%) (Figure 5 ). Regarding the rate of serious hyperkalaemia (≥6.0 mmol/L), 9 , 11 , 13 the sacubitril‐valsartan group had a lower rate than the enalapril or valsartan group with a pooled RR of 0.76, 95% CI 0.65–0.89, P = 0.0007 (P = 0.95 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%) (Figure 4 ). There were no significant differences in the subgroup analyses of the different control groups (Supporting Information, Figure S4 ).

FIGURE 5.

Data of the comparative analysis for the safety outcomes of hyperkalaemia and angioedema. Hyperkalaemia was defined as serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L. Sac/Val, sacubitril‐valsartan.

Angioedema

The composite outcome of angioedema showed no evidence of a significant difference between the sacubitril‐valsartan group and the control group in five trials 9 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 16 with a pooled RR of 1.42, 95% CI 0.52–3.87, P = 0.49 (P = 0.11 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 47%) (Figure 5 ). A sensitivity analysis was further performed by sequentially deleting each study and reanalysing the datasets of all remaining studies. The results showed that the composite outcome of angioedema was elevated in the patients receiving sacubitril‐valsartan in four trials 9 , 11 , 13 , 16 with a pooled RR of 2.19, 95% CI 1.21–3.96, P = 0.009 (P = 0.54 for heterogeneity; I 2 = 0%). These results are shown in Supporting Information, Table S2 .

Discussion

A meta‐analysis of RCTs may provide additional evidence for clinical practice guidelines beyond that provided by individual studies. 17 All studies included in this meta‐analysis were multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, active‐controlled trials with a low risk of bias. The participants included patients with HFrEF or HFpEF, and most patients had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–III HF. The present study is the first to provide composite evidence of primary efficacy outcomes and adverse events of interest among RCTs comparing sacubitril‐valsartan with enalapril or valsartan. These data suggest that sacubitril‐valsartan is superior to an ACE inhibitor or ARB alone in reducing all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular death, or hospitalization for HF in patients with HFrEF but did not result in a significant difference in all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among patients with HFpEF. Despite its association with an increased risk of hypotension, sacubitril‐valsartan showed a reduced incidence of worsening renal function and less frequent elevations in serum potassium. The incidence of angioedema was reduced and similar between the groups.

Sacubitril‐valsartan showed superiority over enalapril or valsartan in terms of the pooled primary efficacy outcomes. Obviously, in the PARADIGM‐HF trial, 11 which had a large number of participants, sacubitril‐valsartan reduced the risks of death from all causes or cardiovascular causes and hospitalization for HF. However, sacubitril‐valsartan did not reduce the risk of death compared with enalapril or valsartan in several other trials, which may be caused by the smaller sample size and shorter follow‐up duration in the PARAMOUNT, 9 PIONEER‐HF, 14 and PRIME studies. 12 Compared with enalapril or valsartan, sacubitril‐valsartan reduced NT‐proBNP to a greater extent in the PARAMOUNT trial 9 and reduced mitral regurgitation to a greater extent in the PRIME study. 12 In the PARAGON‐HF trial, 13 sacubitril‐valsartan did not result in a significantly lower rate of death from cardiovascular causes among patients with HFpEF but did reduce the risk of overall hospitalization for HF in the Lin, Wei, Ying, Yang (LWYY) analysis of investigator‐reported primary endpoints. In a recent post hoc analysis of the PARAGON‐HF trial, 18 sacubitril‐valsartan showed a gradient in relative risk reduction in primary events (including total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death) from patients hospitalized within 30 days to patients never hospitalized. A more favourable effect on the primary endpoint was observed in those with an LVEF of 45–57% compared with those with an LVEF >57% (RR = 0.780; 95% CI 0.641–0.949), 19 demonstrating that the beneficial effects of sacubitril‐valsartan could be amplified when initiated in high‐risk patients with HFpEF. 20 The known benefits of sacubitril‐valsartan in patients with HFrEF 11 may be influenced by excluding higher‐risk patients or different participants. In the PIONEER trial, 21 sacubitril‐valsartan reduced the rates of clinical events committee‐adjudicated cardiovascular death or rehospitalization for HF by 42% (P = 0.007) in patients with post‐acute decompensated heart failure. The TRANSITION study 22 showed that the early initiation of sacubitril‐valsartan was selected for patients with acute decompensated heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction either in the hospital or shortly after discharge. A real‐world study involving 932 HFrEF patients verified the effectiveness of sacubitril‐valsartan. 23

In the PARAGON‐HF study 13 and PARADIGM‐HF study, 11 which had large sample sizes, sacubitril‐valsartan obviously increased the risk of symptomatic hypotension, although these trials excluded some patients due to adverse events during the run‐in phase. Patients with a systolic blood pressure (SBP) <100 mmHg were also excluded during the screening phase. According to the outcomes of this meta‐analysis, sacubitril‐valsartan increased the incidence of symptomatic hypotension with an OR 1.55 (P < 0.0001) compared with enalapril or valsartan. This finding coincides with the result that sacubitril‐valsartan had a greater anti‐hypertensive efficacy than ARBs in elderly hypertensive patients in reducing both the mean sitting SBP and mean ambulatory SBP. 24 Regarding this outcome, research has shown that patients with a lower SBP both during the run‐in phase and after randomization but generally tolerated sacubitril‐valsartan had the same relative benefits over enalapril or valsartan as patients with a higher baseline SBP. 25 , 26 There was no difference in the number of participants who needed permanent treatment discontinuation due to hypotension between the randomized treatment groups. 26 The TITRATION study showed that patients with a lower SBP achieved treatment success with a gradual up‐titration method and suggested that a low SBP should not prevent clinicians from considering the initiation of sacubitril‐valsartan. 27 As patients with HF with a lower baseline SBP are not uncommon, the evidence and protocol used for sacubitril‐valsartan in these patients require further study.

Regarding the pooled evidence, sacubitril‐valsartan led to a lower incidence of renal deterioration than enalapril or valsartan. However, the incidence rate differed depending on the level of baseline serum creatinine and eGFR. In the PIONEER‐HF study, 14 the incidence was 13.6% in the sacubitril‐valsartan group and 14.7% in the enalapril group, which is higher than that in other studies with lower serum creatinine levels and eGFR at baseline. The UK HARP‐III study on moderate‐to‐severe chronic kidney disease showed that treatment with sacubitril‐valsartan did not significantly affect kidney function. 24 , 28 In clinical practice, patients with all stages of kidney disease who receive treatment with sacubitril‐valsartan have fewer cardiovascular deaths or hospitalizations for HF than those treated with standard therapy. 23 According to the pooled analysis of serum potassium concentrations greater than 5.5 mmol/L, there was no significant difference between the groups (OR 0.93, P = 0.10), although these concentrations were found in 13.2% of the sacubitril‐valsartan group and 15.3% of the valsartan group (P = 0.048) in the PARAGON‐HF study. 13 However, regarding the rate of serious hyperkalaemia (≥6.0 mmol/L), sacubitril‐valsartan was associated with a lower rate than enalapril or valsartan (OR 0.75, P = 0.0007) in the PARAGON‐HF, 13 PARAMOUNT, 9 and PARADIGM‐HF studies. 11 The risk of angioedema was low in each trial, and there was no significant difference between the groups by the pooled analysis (OR 1.42, P = 0.49). However, the sensitivity analysis showed a higher incidence of angioedema in the sacubitril‐valsartan group after excluding the PIONEER‐HF study. These results provide useful data for future research.

Sacubitril‐valsartan, which consists of the neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril (AHU377) and the ARB valsartan, 29 , 30 is the first drug indicated to be superior to enalapril in reducing mortality or the hospitalization rate for HF in patients with HF and shows potential to improve the outcomes of patients with HF. 31 However, because sacubitril‐valsartan blocks the renin‐angiotensin system and enhances the activity of vasoactive substances, such as bradykinin and natriuretic peptides, 32 , 33 , 34 treatment with sacubitril‐valsartan was associated with a higher rate of symptomatic hypotension, but there was no increase in the discontinuation rate due to adverse effects associated with hypotension. 11 The greater hypotension caused by sacubitril‐valsartan might impair renal perfusion, but several trials involving HF populations, including PARADIGM‐HF, 11 suggested that sacubitril‐valsartan slowed the decline in renal function compared with ACE inhibitors or ARBs alone and discontinuations of the study drug due to renal impairment were less frequent in the sacubitril‐valsartan group. 23 , 31 , 35 , 36 The UK HARP‐III study 28 included 414 participants with moderate‐to‐severe chronic kidney disease and showed that sacubitril‐valsartan was well tolerated and had similar effects on kidney function and albuminuria as irbesartan over 12 months of follow‐up. The outcome of hyperkalaemia was similar to that of worsening renal function. Based on this pooled analysis, sacubitril‐valsartan slowed the elevation in serum potassium compared with ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Angioedema is related to the inhibition of three enzymes that degrade bradykinin. 37 Sacubitril‐valsartan did not increase the risk of serious angioedema because it does not inhibit ACE or aminopeptidase P. 29 , 30 Analyses of Markov model‐simulated HFrEF suggest that the health benefit of sacubitril‐valsartan is cost‐effective compared with the use of enalapril as sacubitril‐valsartan can extend more than 1 year of life in each patient using the medication and help save cost by avoiding hospitalization. 38

Our study has some potential limitations. First, the number of included trials was low, and a funnel plot was not suitable for the sensitivity analysis. Second, confounding factors, such as heart function, baseline blood pressure, age, sex, and other potential factors, were difficult to control. Third, unpublished data or articles published in other languages were not included. Fourth, different sample sizes and different control drugs may have led to confounding bias and affected the composite outcomes. Finally, this meta‐analysis may be underpowered for a long‐term adverse event comparison between sacubitril‐valsartan and ARBs or ACE inhibitors due to the different durations of the included RCTs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the pooled estimates showed that compared with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, sacubitril‐valsartan significantly decreased the risk of death from all causes or cardiovascular causes and hospitalization for HF in patients with HFrEF but failed to improve all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in HFpEF cohorts. Sacubitril‐valsartan increased the risk of symptomatic hypotension but slowed the decline in kidney function and elevation in serum potassium concentration compared with ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Angioedema occurred less frequently in the sacubitril‐valsartan group.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81860068).

Author contributions

Hongzhou Zhang and Tieqiu Huang reviewed the articles, performed the meta‐analysis and wrote the manuscript. Wen Shen, Pingping Yang, and Xiuxiu Xu were responsible for the statistical analysis. Tao Wu and Yanqing Wu provided editing assistance, and Qinghua Wu designed and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and agreed on this information before submission.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Risk of bias of included studies. (A) Risk of bias graph. (B) Risk of bias summary.

Figure S2. Data of the comparative subgroup analysis with different control groups for symptomatic hypotension. Abbreviations: Sac/Val: sacubitril‐valsartan.

Figure S3. Data of the comparative subgroup analysis with different control groups for worsening renal function. Worsening renal function was defined as a decrease in eGFR ≥35% or an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.5 mg/dL from baseline AND a decrease in eGFR of ≥25% from baseline or serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL. Abbreviations: Sac/Val: sacubitril‐valsartan.

Figure S4. Data of the comparative subgroup analysis with different control groups for hyperkalaemia. Hyperkalaemia was defined as serum potassium >5.5 mmol/l. Abbreviations: Sac/Val: sacubitril‐valsartan.

Table S1. Characteristics of RCTs included in the study

Table S2. Sensitivity analysis of angioedema.

Zhang, H. , Huang, T. , Shen, W. , Xu, X. , Yang, P. , Zhu, D. , Fang, H. , Wan, H. , Wu, T. , Wu, Y. , and Wu, Q. (2020) Efficacy and safety of sacubitril‐valsartan in heart failure: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 3841–3850. 10.1002/ehf2.12974.

References

- 1. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, American College of Cardiology F and American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G . 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: e147–e239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berry C, Murdoch DR, McMurray JJ. Economics of chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2001; 3: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics C and Stroke Statistics S . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014; 129: e28–e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang P, Shen W, Chen X, Zhu D, Xu X, Wu T, Xu G, Wu Q. Comparative efficacy and safety of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure: a network meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart Fail Rev 2019; 24: 637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asgar AW, Mack MJ, Stone GW. Secondary mitral regurgitation in heart failure: pathophysiology, prognosis, and therapeutic considerations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65: 1231–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hubers SA, Brown NJ. Combined angiotensin receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition. Circulation 2016; 133: 1115–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruilope LM, Dukat A, Bohm M, Lacourciere Y, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP. Blood‐pressure reduction with LCZ696, a novel dual‐acting inhibitor of the angiotensin II receptor and neprilysin: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, active comparator study. Lancet 2010; 375: 1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, Voors A, Shah A, Kraigher‐Krainer E, Shi V, Bransford T, Takeuchi M, Gong J, Lefkowitz M, Packer M, McMurray JJ. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a phase 2 double‐blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau J, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Committees P‐H, Investigators . Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM‐HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15: 1062–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR. Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kang DH, Park SJ, Shin SH, Hong GR, Lee S, Kim MS, Yun SC, Song JM, Park SW, Kim JJ. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor for functional mitral regurgitation. Circulation 2019; 139: 1354–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Ge J, Csp L, Maggioni AP, Martinez F, Packer M, Pfeffer MA, Pieske B, Redfield MM, Rouleau JL, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Zile MR, Desai AS, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Boytsov SA, Comin‐Colet J, Cleland J, Dungen HD, Goncalvesova E, Katova T, Kerr Saraiva JF, Lelonek M, Merkely B, Senni M, Shah SJ, Zhou J, Rizkala AR, Gong J, Shi VC, Lefkowitz MP. Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, Duffy CI, Ambrosy AP, McCague K, Rocha R, Braunwald E. Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desai AS, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Claggett BL, Fang JC, Izzo J, McCague K, Abbas CA, Rocha R, Mitchell GF. Effect of sacubitril‐valsartan vs enalapril on aortic stiffness in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA; 322: 1077–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Desai AS, Anker SD, Perrone SV, Janssens S, Milicic D, Arango JL, Packer M, Shi VC, Lefkowitz MP, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Prior heart failure hospitalization, clinical outcomes, and response to sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan in HFpEF. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 75: 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Del Buono MG, Bonaventura A, Vecchie A, Wohlford GF, Dixon DL, Van Tassel BW, Abbate A. Sacubitril‐valsartan for the treatment of heart failure: time for a paragon? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2020; 75: 105–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Del Buono MG, Iannaccone G, Scacciavillani R, Carbone S, Camilli M, Niccoli G, Borlaug BA, Lavie CJ, Arena R, Crea F, Abbate A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction diagnosis and treatment: an updated review of the evidence. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020; S0033–0620(20)30083–9. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.011 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morrow DA, Velazquez EJ, DeVore AD, Desai AS, Duffy CI, Ambrosy AP, Gurmu Y, McCague K, Rocha R, Braunwald E. Clinical outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure randomly assigned to sacubitril/valsartan or enalapril in the PIONEER‐HF trial. Circulation 2019; 139: 2285–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wachter R, Senni M, Belohlavek J, Straburzynska‐Migaj E, Witte KK, Kobalava Z, Fonseca C, Goncalvesova E, Cavusoglu Y, Fernandez A, Chaaban S, Bohmer E, Pouleur AC, Mueller C, Tribouilloy C, Lonn E, Alb J, Gniot J, Mozheiko M, Lelonek M, Noe A, Schwende H, Bao W, Butylin D, Pascual‐Figal D, Investigators T . Initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in haemodynamically stabilised heart failure patients in hospital or early after discharge: primary results of the randomised TRANSITION study. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 998–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang HY, Feng AN, Fong MC, Hsueh CW, Lai WT, Huang KC, Chong E, Chen CN, Chang HC, Yin WH. Sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients: real world experience on advanced chronic kidney disease, hypotension, and dose escalation. J Cardiol 2019; 74: 372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. De Vecchis R, Ariano C, Soreca S. Antihypertensive effect of sacubitril/valsartan: a meta‐analysis. Minerva Cardioangiol 2019; 67: 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bohm M, Young R, Jhund PS, Solomon SD, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Packer M, McMurray JJV. Systolic blood pressure, cardiovascular outcomes and efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: results from PARADIGM‐HF. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 1132–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J, Pearson SM, Desai AS, Packer M, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Swedberg K, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with hypotensive episodes among heart failure patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan or enalapril: The PARADIGM‐HF trial (prospective comparison of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure). Circ Heart Fail 2018; 11: e004745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Senni M, McMurray JJV, Wachter R, McIntyre HF, Anand IS, Duino V, Sarkar A, Shi V, Charney A. Impact of systolic blood pressure on the safety and tolerability of initiating and up‐titrating sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: insights from the TITRATION study. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haynes R, Judge PK, Staplin N, Herrington WG, Storey BC, Bethel A, Bowman L, Brunskill N, Cockwell P, Hill M, Kalra PA, McMurray JJV, Taal M, Wheeler DC, Landray MJ, Baigent C. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan versus irbesartan in patients with chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2018; 138: 1505–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gu J, Noe A, Chandra P, Al‐Fayoumi S, Ligueros‐Saylan M, Sarangapani R, Maahs S, Ksander G, Rigel DF, Jeng AY, Lin TH, Zheng W, Dole WP. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of LCZ696, a novel dual‐acting angiotensin receptor‐neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi). J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 50: 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hegde LG, Yu C, Renner T, Thibodeaux H, Armstrong SR, Park T, Cheruvu M, Olsufka R, Sandvik ER, Lane CE, Budman J, Hill CM, Klein U, Hegde SS. Concomitant angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition produces omapatrilat‐like antihypertensive effects without promoting tracheal plasma extravasation in the rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2011; 57: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Solomon SD, Claggett B, McMurray JJV, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Combined neprilysin and renin–angiotensin system inhibition in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta‐analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 1238–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vardeny O, Miller R, Solomon SD. Combined neprilysin and renin‐angiotensin system inhibition for the treatment of heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2014; 2: 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Buggey J, Mentz RJ, DeVore AD, Velazquez EJ. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition in heart failure: mechanistic action and clinical impact. J Card Fail 2015; 21: 741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andersen MB, Simonsen U, Wehland M, Pietsch J, Grimm D. LCZ696 (valsartan/sacubitril)—a possible new treatment for hypertension and heart failure. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2016; 118: 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Voors AA, Gori M, Liu LC, Claggett B, Zile MR, Pieske B, McMurray JJ, Packer M, Shi V, Lefkowitz MP, Solomon SD, Investigators P. Renal effects of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17: 510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Packer M, Claggett B, Lefkowitz MP, McMurray JJV, Rouleau JL, Solomon SD, Zile MR. Effect of neprilysin inhibition on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic heart failure who are receiving target doses of inhibitors of the renin‐angiotensin system: a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM‐HF trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fryer RM, Segreti J, Banfor PN, Widomski DL, Backes BJ, Lin CW, Ballaron SJ, Cox BF, Trevillyan JM, Reinhart GA, von Geldern TW. Effect of bradykinin metabolism inhibitors on evoked hypotension in rats: rank efficacy of enzymes associated with bradykinin‐mediated angioedema. Br J Pharmacol 2008; 153: 947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gaziano TA, Fonarow GC, Claggett B, Chan WW, Deschaseaux‐Voinet C, Turner SJ, Rouleau JL, Zile MR, McMurray JJ, Solomon SD. Cost‐effectiveness analysis of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol 2016; 1: 666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Risk of bias of included studies. (A) Risk of bias graph. (B) Risk of bias summary.

Figure S2. Data of the comparative subgroup analysis with different control groups for symptomatic hypotension. Abbreviations: Sac/Val: sacubitril‐valsartan.

Figure S3. Data of the comparative subgroup analysis with different control groups for worsening renal function. Worsening renal function was defined as a decrease in eGFR ≥35% or an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.5 mg/dL from baseline AND a decrease in eGFR of ≥25% from baseline or serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL. Abbreviations: Sac/Val: sacubitril‐valsartan.

Figure S4. Data of the comparative subgroup analysis with different control groups for hyperkalaemia. Hyperkalaemia was defined as serum potassium >5.5 mmol/l. Abbreviations: Sac/Val: sacubitril‐valsartan.

Table S1. Characteristics of RCTs included in the study

Table S2. Sensitivity analysis of angioedema.