Abstract

This study aims to update new knowledge regarding foetal cardiovascular response to anaemia, using foetal haemoglobin Bart's disease as a study model. Original research articles, review articles, and guidelines were narratively reviewed and comprehensively validated. The main foetal cardiovascular changes in response to anaemia are consequences of hypervolaemia and increased cardiac output to meet tissue oxygen requirement. New challenging insights are as follows: (i) the earliest morphological change is an increase in cardiac size and remodelling of the sphericity (an increase in diameter more pronounced than that in long axis) followed by several markers, such as placentomegaly and hepatosplenomegaly. (ii) The earliest functional change is increased peak systolic velocity of the red blood cells because of low viscosity, especially in the middle cerebral artery. (iii) The foetal heart has very high reserve potentials to cope with anaemia: increasing workload without increased central venous pressure and increased myocardial performance without compromising shortening fraction. This hard‐working period with good performance lasts long, including most part of the second and third trimester. (iv) At the time cardiomegaly myocardial cellular damage has already occurred, in spite of good cardiac function. (v) Anaemic hydrops foetalis is mainly due to hypervolaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, and high vascular permeability, not heart failure. (vi) Foetal heart failure occurs only when the adaptive mechanism becomes exhausted or long after the development of anaemic hydrops foetalis. Heart failure is a very late result of a longstanding overworked heart. (vii) Ultrasound is highly effective in the detection of foetal response to anaemia. An increase in cardiac size and middle cerebral artery is very helpful in predicting the affected foetuses in pre‐hydropic phase. (viii) Theoretically, intrauterine treatment of anaemic hydrops results in satisfactory outcomes as long as cardiac function is normal, but intrauterine intervention should be strongly considered in pre‐hydropic phase because myocardial cell damage could have already occurred in this phase or early hydropic phase. Anaemic hydrops foetalis is not primarily caused by heart failure as commonly advocated, but it is rather a consequence of hypervolaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, and high vascular permeability while heart failure is a very late consequence of a longstanding overworked heart. New insights gained from this review may be useful to base clinical practice on which sonographic markers imply significant pathological changes, how ultrasound can be helpful in early detection of anaemic response, when intrauterine transfusion for anaemia due to non‐lethal causes should be administered, etc.

Keywords: Anaemia, Foetus, Heart failure, Haemoglobin Bart's disease, Hydrops foetalis, Ultrasound

Introduction

Foetal anaemia is a relatively rare but serious disorder. The aetiology of foetal anaemia varies with geographical areas. In the western world, alloimmunization is the most common cause, 1 followed by non‐immune anaemia, such as parvovirus B19 infection, haemoglobinopathies, foeto‐maternal haemorrhage, and twin‐to‐twin transfusions. In Asia, especially Southeast Asia, haemoglobin (Hb) Bart's disease or homozygous α‐thalassemia‐1 is the most common cause of severe foetal anaemia, accounting for about 60–80% of hydrops foetalis cases in Thailand. 2 Understanding foetal response to anaemia would be helpful in clinical decision making regarding when intrauterine intervention should be instituted, what haemodynamic parameters should be used to evaluate foetal insults or long‐term prognosis, how to predict foetal cell damage secondary to anaemic hypoxia, etc. Nevertheless, to date, knowledge on foetal response to anaemia is very limited because there are several barriers to its study, such as the limitation in invasive intrauterine evaluation due to ethical reasons and the therapeutic effects on the natural course of foetal deterioration caused by anaemic hypoxia. The mechanism by which anaemia impacts childhood and adult health has been extensively studied, leading to successful management. However, knowledge on its impact on foetal life is very limited, and the extent to which foetal anaemia without treatment could negatively impact on later life has never been thoroughly explored. This is because of the several limitations associated with conducting a study on live foetuses in utero. Theoretically, anaemic hypoxia tends to cause cellular damage that affects health in later life based on the concept of foetal origin of adult disease or foetal programming. We can expect that many foetuses with non‐lethal α‐thalassemia have anaemic hypoxia with some degree of cellular damage, but we have no solid evidence to clarify the association and the extent of the hypoxic injuries. Nevertheless, we can study the mechanism by which anaemia can destroy the cellular structures of the developing vital organs using foetal Hb Bart's disease as a research model. Because foetuses with Hb Bart's disease, a lethal form of α‐thalassemia, are usually diagnosed at various stages and termination of pregnancy is ethically justified, we are able to perform extensive study on molecular and cellular changes in developing vital organs at various phases: (i) the phase of no sonomarkers, early diagnosed by chorionic villous sampling in cases at risk, (ii) the phase of pre‐hydropic signs, and (iii) the phase of hydrops foetalis. The main purpose of this review is to provide an update on foetal haemodynamic responses to anaemia based on extensive studies on foetal Hb Bart's disease. We hope that the knowledge gained will serve as the basis for management guidelines, counselling, and predicting the prognosis of foetal anaemia due to any cause, as well as future studies. Nevertheless, the results of this review should be interpreted with cautions in terms of application for foetal anaemia secondary to other causes because the natural history of disease might be different and foetal Hb Bart's disease cannot perfectly represent anaemia due to other causes.

Methods of review

A search strategy was used to identify peer‐reviewed manuscripts published between January 1990 and December 2019, using the following databases: PubMed, SCOPUS, andWeb of Science. The article types included original researches, reviews, and guidelines. The search was updated April 2020. Two authors independently assessed title, abstract, and full text of the studies meeting the inclusion criteria, specifically foetal anaemia and Hb Bart's disease. The key words were foetal anaemia, Hb Bart's disease, and ultrasound. Data were extracted, and a quality assessment was conducted.

Haemodynamic changes in foetal haemoglobin Bart's disease

α‐Thalassemia is caused by defective synthesis of α‐globin chains and is the most common cause of non‐immune hydrops foetalis in Southeast Asia. The α‐globin genes consist of two loci on each homologous chromosome 16 (αα/αα). Hb Bart's disease or homozygous α‐thalassemia‐1(‐‐/‐‐) is invariably lethal, or hydropic. If both parents have α‐thalassemia‐1 trait (‐‐/αα), the inheritance risk for foetal Hb Bart's disease is 25%. In foetal Hb Bart's disease, normal foetal Hb (α2γ2) cannot be produced; instead, an abnormal type, Hb Bart's (γ4), is produced. Red blood cells consisting of Hb Bart's poorly transport oxygen are destroyed rapidly by the reticuloendothelial system, leading to foetal anaemia. 3

Foetuses with Hb Bart's disease show various degrees of anaemia from late first trimester, when the foetuses undergo Hb switching from embryonic Hb to α‐globin chain, depending on the capability of compensatory haematopoiesis and adaptation to anaemic hypoxia, resulting in different timelines of gestational age in the progressive development of various haemodynamic changes. According to extensive prenatal studies on foetal Hb Bart's disease, 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 foetal cardiovascular changes in affected foetuses show a progressive change with advancing gestational age, from late first trimester onwards. Typically, the haemodynamic changes may be divided into two main stages 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 : (i) high‐output stage, including pre‐hydropic and hydropic phases, and (ii) low‐output stage or cardiac failure. Affected foetuses show a similar pattern of progressive development, but there is time difference in the first appearance of abnormalities.

High‐output stage

In foetal anaemia, the foetus adapts to cope with the low tissue oxygenation by increasing blood volume (hypervolaemia) and cardiac output. Note that we intentionally use the term of high‐output stage rather than heart failure because most foetuses have increased cardiac output without signs of poor cardiac function or increased preload most of the time. This stage may be subdivided into two phases 6 , 9 , 15 , 17 :

Pre‐hydropic phase: In this early phase, the cardiovascular function of anaemic foetuses is increased to maintain tissue oxygen perfusion. They use reserve potentials to avoid anaemic hypoxia in body tissues. In this phase, the foetal organs work harder than those of normal foetuses, similar to the response to exercise to deliver oxygen meeting the requirement, but do not develop hydropic changes yet. The main mechanisms utilized to increase tissue perfusion are as follows: (i) increasing cardiac output by increasing cardiac size and total blood volume (hypervolaemia) and (ii) increasing the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow and reticuloendothelial system. These adaptations produce several pre‐hydropic sonographic signs, permitting early detection of anaemia.

Hydropic phase: Hypervolaemia, high vascular permeability, and hypoalbuminaemia facilitate fluid leakage into third spaces, resulting in fluid collection in various spaces, that is, ascites, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and subcutaneous oedema. Several studies on Hb Bart's disease strongly indicate that anaemic hydrops is not caused by heart failure as commonly advocated, 19 , 20 but it is associated with hypervolaemia with high vascular permeability, while heart failure is a very late consequence of a longstanding overworked heart, long after the development of hydrops.

Currently, with extensive ultrasound studies, foetuses with Hb Bart's disease have been prenatally diagnosed in early pre‐hydropic phase, before the development of hydrops. Most cases are detected in the first half of pregnancy. 6 , 11 Leung et al. 15 showed that the overall sensitivity and specificity of pre‐hydropic markers (12–30 weeks) are 100% and 95%, respectively.

Molecular changes

We compared mitochondrial function [mitochondrial swelling, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production levels, and JC‐1], oxidative stress, inflammatory markers, and apoptosis markers in the foetal cardiac tissue between 18 foetuses with Hb Bart's disease and 10 non‐anaemic controls in early second trimester. 21 We found that foetal anaemic hypoxia is significantly associated with cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction (Figure 1 ). All of them had normal cardiac function, assessed just before pregnancy termination. Cardiac mitochondrial swelling, mitochondrial depolarization, ROS production levels, and tumour necrosis factor‐α, as well as active caspase‐3 and Bcl‐2 expression were significantly higher in the affected foetuses. Accordingly, in spite of clinically normal cardiac function, foetal anaemia is significantly associated with myocardial cell damage, regardless of the presence of hydrops. Whether or not the anaemic insults can be completely recovered by intrauterine treatment or it can place them to be at a higher risk of adult cardiovascular diseases by foetal programming has yet to be elucidated.

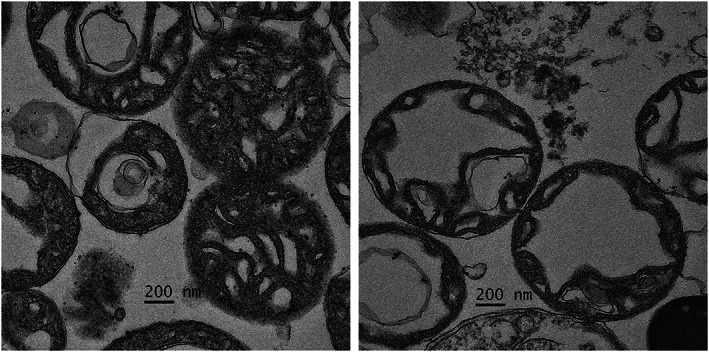

Figure 1.

Cardiac mitochondrial morphology by transmission electron microscopy (magnification ×3000). Left: Depicts mitochondria from a normal foetus; the mitochondria are normal morphology with intact cristae. Right: Represents mitochondria from haemoglobin Bart's foetuses (19 weeks of gestation) illustrating swollen mitochondria with abnormal circular cristae.

Morphological changes

Most morphological changes are consequences of hypervolaemia and extra‐medullary haematopoiesis. In foetal Hb Bart's disease, change in cardiac size, usually evaluated by cardiac diameter to thoracic diameter ratio (CTR), may be observed as early as late first trimester. Typically, morphological changes are summarized as follows (Table 1 ):

Cardiomegaly: Increased cardiac size is the most common and earliest ultrasound marker of foetal anaemia. Several techniques are proposed to assess the cardiac size, such as cardiac circumference, 27 cardiac diameter, area and volume, 34 CTR, 9 , 15 and cardiac diameter to biparietal diameter ratio. 25 Among them, CTR is most commonly used in clinical practice to predict foetal Hb Bart's disease among foetuses at risk. 14 , 15 , 22 This is due to its convenience, simplicity, reproducibility, less time consumption, short learning curve, and, most importantly, high efficacy in predicting affected foetuses. In late first trimester (12–15 weeks), CTR (at a cut‐off point of 0.48) has a sensitivity of 90–100% and a false‐positive rate of 7–10%. 6 , 22 , 23 The performance of CTR is even higher when combined with middle cerebral artery–peak systolic velocity (MCA‐PSV). 23 Likewise, at mid‐pregnancy (18–22 weeks), CTR has a sensitivity of 95–100%. 9 , 11 , 15 , 23 It is noteworthy that in spite of cardiac dilatation, the ventricular wall thickness is slightly increased, with minimal or no hypertrophy. 28 The finding suggests that foetal anaemia probably causes volume load rather than pressure load on the myocardium.

Cardiac remodelling: An increase in cardiac width is more striking than that of cardiac length or decreased global sphericity index (GSI: cardiac length to cardiac diameter ratio). As a result, the heart is more globular. Tongsong et al. 28 demonstrated that the GSI of 54 foetuses with Hb Bart's disease at mid‐pregnancy was significantly lower than those of 161 normal foetuses (1.11 ± 0.06 vs. 1.26 ± 0.09, P‐value: 0.017). GSI can predict affected foetuses with a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 88%.

Enlarged placenta: In foetuses with Hb Bart's disease, placental size is progressively increased with advancing gestation. 13 , 23 Convincingly, placentomegaly is a consequence of hypervolaemia, causing fluid leakage from chorionic vessels into the interstitial space, resulting in hydropic villi and placental enlargement. Clinically, increased placental thickness may be sonographically observed from the late first trimester. 10 , 29 The thickness is more obvious in late gestation. Placental thickness is also used to predict affected foetuses in clinical practice. Among foetuses at risk of Hb Bart's disease, placental thickness has a sensitivity of about 70% and specificity of about 65%, 6 , 23 in late first trimester. The sensitivity is increased to 74–88% 9 , 13 at mid‐pregnancy. The placenta of foetal Hb Bart's disease in last trimester often weighs 1–2 kg.

Hepatosplenomegaly: The liver and spleen are also progressively enlarged with gestational age and severity of anaemia. The enlargement is caused by hypervolaemia and increased function. In foetal anaemia, to meet tissue oxygen perfusion requirement, the reticuloendothelial system increases extra‐medullary haematopoiesis. Additionally, the enlargement promotes portal hypertension and hepatic dysfunction or hypoalbuminaemia, resulting in even more extravascular fluid leakage and hydropic changes. Clinically, assessment of the liver and splenic size is also helpful in predicting foetal anaemia among foetuses at risk. 30 , 31 However, the diagnostic performance is inferior to CTR and MCA‐PSV.

Nuchal translucency (NT): NT is fluid collection between the nuchal skin and nuchal soft tissue. It is a small amount of fluid that can be observed in normal foetuses in late first trimester and usually disappears thereafter. It is widely used for foetal Down syndrome screening at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Thickened NT may be found in approximately 17% of foetuses affected with Hb Bart's disease. 6 The mechanism is unclear, but it is possible that anaemia‐related hypervolaemia promotes such fluid collection. Only a small portion of affected foetuses show thickened NT; this may be due to the fact that the gestational age of NT is too early for the occurrence of anaemia caused by Hb Bart's disease.

Polyhydramnios/oligohydramnios: Anaemic foetuses have increased cardiac output and hypervolaemia as mentioned earlier, leading to an increase in circulating blood volume, which results in increased renal blood flow and urine output as well as amniotic fluid volume. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 However, polyhydramnios is usually obvious in the second or third trimester. In severe cases like Hb Bart's foetuses, anaemic hypoxia is so severe and reduces renal blood flow, resulting in oliguria and decreased amniotic fluid or oligohydramnios. 39 Different from anaemia due to other causes, Hb Bart's foetuses show polyhydramnios in only 10% of cases, reflective of a more severe anaemic hypoxia.

Hydropic signs: Hydrops foetalis is defined as fluid collection in the third spaces of the body, at least two spaces. It usually develops when foetal haematocrit level becomes less than 15%. 40 The common fluid collections are ascites, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and subcutaneous oedema. In foetuses with Hb Bart's disease, hydrops often develops in the second half of pregnancy, but it can appear as early as in the first trimester. Hydropic signs are associated with increased severity of anaemia, which is highly correlated with advancing gestation. It is worthy of note that hydropic signs develop a long period after the first appearance of pre‐hydropic signs like cardiomegaly and high MCA‐PSV, although in severe cases, hydrops could rapidly develop in late first trimester. Hydrops foetalis secondary to anaemia always develops after cardiomegaly. 6 , 9 Importantly, hydrops is not a sign of heart failure, as mostly stated. 20 , 41 , 42 This is due to the fact that most foetuses have already developed hydrops foetalis without signs of heart failure, when defined as a condition that the heart has poor performance resulting in adequate tissue oxygen perfusion reflected by poor contractility or increased central venous pressure, while foetal electrocardiogram and tissue asphyxia cannot be directly assessed in utero. As long as cardiac function is good, intrauterine transfusion can completely convert the hydropic process and result in satisfactory outcomes. 43 , 44 Although hydrops due to various causes is usually associated with poor prognosis, anaemic hydrops has better outcomes if timely intervention is provided. The hydropic signs are as follows 39 :

Ascites and pericardial/pleural effusions: The severity of ascites is widely variable. In Hb Bart's disease, it is demonstrated in nearly all cases in late gestation and is easily observed by subjective evaluation of the free fluid lining the outer border of the visceral organs. Nevertheless, even in advanced cases, ascites may be very minimal because the enlarged liver and spleen occupy nearly the entire abdominal cavity, with no space left for fluid collection. Likewise, the severities of pericardial and pleural effusions are not always correlated with the severity of anaemia. They usually appear long after cardiomegaly and high MCA‐PSV. Importantly, the effusion can only be minimal because the heart occupies nearly the entire thoracic cavity.

Subcutaneous oedema: It is a late sonographic sign of foetal anaemia, observed in only advanced cases, long after the first appearance of cardiomegaly. It is obvious in late gestation, predominantly on the scalp. Generally, it is not as severe as observed in cases of lymphatic/venous obstruction, commonly observed in cystic hygroma or chromosome abnormality.

Dilated umbilical vein: In advanced Hb Bart's hydrops, the umbilical vein is markedly dilated, especially the intra‐abdominal part, which is clearly observed in the liver. 39 Also, the ductus venosus is abnormally dilated 39 and is easier to identify.

Table 1.

Appearance of cardiovascular changes in responses to anaemia in foetal haemoglobin Bart's disease at various gestational age timelines

| Study | Late first trimester | Early second trimester | Late second trimester | Early third trimester | Late third trimester |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological changes | |||||

| Cardio‐thoracic diameter ratio 6 , 9 , 12 , 15 , 22 , 23 , 24 | + | +++ | ++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| Cardio‐biparietal diameter ratio 25 , 26 | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++++ | |

| Cardiac circumference/area 24 , 27 | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++++ | |

| Global sphericity index 28 | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Placental thickness 6 , 9 , 15 , 23 , 29 | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ |

| Liver length 30 | + | + | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Splenic circumference 31 | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

| Hydrops 9 | + | ++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| Functional changes | |||||

| Cardiac output 18 | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑↑ | ↑ → ↑↑↑↑ | ↓↓ |

| Tei index (increased) 4 | ↔ | ↔ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑↑ |

| Ductus venosus a‐wave 7 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| Shortening fraction 8 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↓↓ |

| Umbilical venous pulsations | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| MCA‐PSV 6 , 23 , 30 , 32 | + | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| SpA‐PSV 33 | + | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

MCA‐PSV, middle cerebral artery–peak systolic velocity (defined as abnormal when the measured value is greater than 1.5 multiple of median); SpA‐PSV, splenic artery–peak systolic velocity.

A plus sign (+) represents the strength of evidence based on proportion or percentage of cases showing the abnormal signs from a small proportion (+) to all or nearly all cases (+++++). The arrow sign represents severity (quantitative) of signs from a minimal increase (↑) to a mild, moderate, and marked increase (↑↑↑↑) or no change (↔), and similar is a decrease sign (↓). The intensity of the effects was validated with consensus by the author team.

Functional changes

As consequences of increased cardiac output and hypervolaemia in foetal anaemia, several haemodynamic changes occur, as follows (Table 1 ):

Increased MCA‐PSV: In foetal anaemia, blood viscosity is decreased, making the red blood cell flow more rapidly. As a result, Doppler studies show high velocity of blood flow in several great vessels. Measurement of MCA‐PSV is most commonly used in practice for evaluation of whether anaemia is caused by Hb Bart's disease, Rh alloimmunization, parvovirus B19, etc. In the second trimester, MCA‐PSV, using a cut‐off of 1.5 MoM, has a sensitivity of 64.3–85% and specificity of 98.6–100%. 23 , 32 When combined with CTR, the sensitivity is as high as 100% without compromising the specificity. In clinical use, measurement of CTR in combination with MCA‐PSV is used in screening for foetal Hb Bart's disease among foetuses at risk. Currently, MCA‐PSV is used as a non‐invasive tool in the assessment of foetuses at risk of foetal hydrops secondary to Rh isoimmunization. It is used as a guide to select cases for invasive diagnosis of anaemia and as a follow‐up tool after treatment.

Increased cardiac output: In foetuses with Hb Bart's disease, cardiac output is shown to increase from late first trimester until late gestation. 18 It only decreases when cardiac decompensation is in a very advanced stage.

Hyperdynamic state: Foetuses with anaemia are in a hyperdynamic state because of high cardiac output and hypervolaemia, as mentioned earlier. 18 The large blood volume crossing the foramen ovale causes the septum primum excursion (SPE) and SPE index (the ratio of SPE to the left atrial diameter) to increase. 45 Sirilert et al. 45 demonstrated that SPE can be used to predict affected foetuses, giving a sensitivity and specificity of 75.0% and 72.7%, respectively, at a cut‐off point of 1.3 MoM. Additionally, trivial tricuspid regurgitation is much more common, possibly caused by incomplete atrioventricular valve closures of the enlarged atrioventricular valve annulus.

Cardiac function; myocardial performance index or Tei index: During high‐output state in both pre‐hydropic and hydropic phases, Tei index is significantly increased compared with normal foetuses. 4 Nevertheless, the performance is still in the normal reference range, even in frank hydrops. In other words, the myocardium works harder but still works well. Luewan et al. 46 demonstrated that in foetuses with Hb Bart's disease at 12–14 weeks, the median isovolumetric contraction time (ICT) and Tei index were significantly increased compared with those in normal foetuses, whereas other Doppler indices were not significantly different. This finding indicated that foetuses with anaemia have subtle changes in myocardial function from late first trimester, and the earliest sign is prolonged ICT. Similarly, Tongprasert et al. 47 demonstrated that among foetuses with Hb Bart's disease at mid‐pregnancy (18–22 weeks), ICT was significantly longer compared with unaffected foetuses. Additionally, ICT can effectively predict affected foetuses, giving a sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 79% (at a cut‐off of 40 ms). The two studies indicate that prolonged ICT is an early Doppler marker in response to foetal anaemia, implying that ventricular systolic function is firstly affected in response to anaemia. Different from the condition of increased afterload, like foetal growth restriction, in which isovolumetric relaxation time is the most sensitive marker, 48 foetal anaemia firstly interferes with ICT or systolic function. Moreover, during the high‐output state, ventricular diastolic function was normal when assessed with colour M‐mode propagation velocity, and ventricular diastolic compromise is a late occurring consequence of longstanding volume load. 49

Cardiac function; shortening fraction: During the high‐output state in pre‐hydropic and hydropic phases, in spite of marked cardiac enlargement and increased cardiac output, the cardiac function is still normal (Figure 2 ). Tongsong et al. 8 demonstrated that foetuses with Hb Bart's hydrops foetalis have a relatively good shortening fraction compared with hydropic foetuses secondary to cardiac defects. Hydrops associated with cardiac defect is caused by cardiac failure, whereas anaemic hydrops is likely caused by hypervolaemia with high vascular permeability.

Cardiac preload: In the high‐output state, in spite of the increase in cardiac output and blood volume in foetal anaemia, foetuses with Hb Bart's diseases have normal cardiac preload (assessed with Doppler waveforms of the ductus venosus 7 and the inferior vena cava 5 ). These studies demonstrated that during atrial contraction, there is high forward flow (positive a‐wave) in the ductus venosus, indicating normal central venous pressure. Abnormal preload is observed only when heart failure has already developed.

Afterload: Placental resistance is not increased, as assessed by umbilical artery Doppler indices. Anaemic foetuses can perfectly maintain normal diastolic flow. Additionally, some studies on myocardial performance indicated that isovolumetric relaxation time is unchanged in foetal anaemia, 46 , 47 suggesting no significant impact on afterload in spite of increased blood volume.

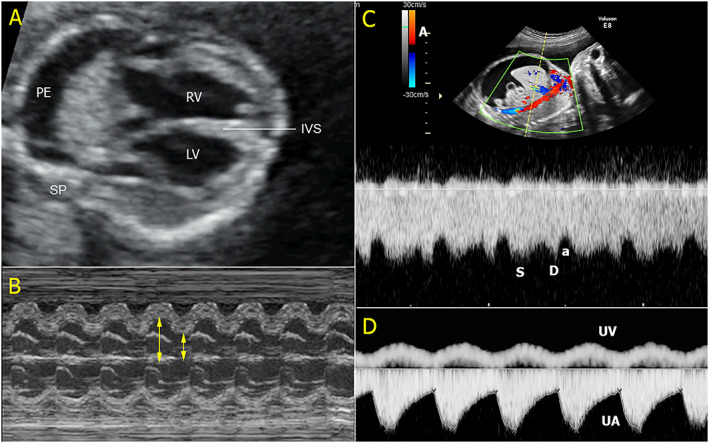

Figure 2.

An example of high‐output hydrops foetalis. (A) The four‐chamber view shows marked cardiomegaly with pleural effusion (IVS, interventricular septum; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; PE, pleural effusion; SP, spine); (B) good contractility on M‐mode; (C) Doppler spectral waveforms of the ductus venosus show high forward flow during atrial contraction (a, a‐wave; d, diastole; s, systole); and (D) umbilical artery (UA) and umbilical vein (UV) Doppler waveforms show normal blood flow in UA but venous pulsations in the UV.

Low‐output stage

The foetal heart has very high reserve potentials. Heart failure usually occurs after a long period of anaemic hydrops foetalis. Even in foetal Hb Bart's hydrops, heart failure usually occurs in late last trimester, while hydrops foetalis has already developed in early‐to‐middle second trimester. In this state, the cardiac compensatory mechanism is exhausted, resulting in too low cardiac output to meet the requirement of tissue perfusion, leading to non‐reassuring foetal status and stillbirth or neonatal death. Doppler velocity and 2D ultrasound features in this state are as follows (Figure 3 ):

Increased cardiac preload: The Doppler studies of blood flow in the ductus venosus 7 and foetal inferior vena cava 5 support that hydrops is associated with cardiac defect and only advanced cases of foetal Hb Bart's disease have increased preload (increased central venous pressure). Luewan et al. 5 showed that the cardiac preload of the inferior vena cava of 54 foetuses with Hb Bart's hydrops foetalis of less than 28 weeks were within normal ranges, while that of foetuses with Hb Bart's hydrops foetalis of greater than 28 weeks were obviously increased.

Poor cardiac function: In this stage, the overall cardiac function is poor. There is a significant increase in Tei index and a decrease in foetal cardiac output, which is obviously low 18 ; also, shortening fraction is very poor. 8

Oligohydramnios: In the advanced stage of Hb Bart's disease, oligohydramnios is observed in most cases. This is likely associated with the reduction of renal blood flow and urine production, caused by severe anaemic hypoxia. 39 Based on clinical observation, oligohydramnios usually develops much earlier than cardiac failure.

Non‐reassuring foetal well‐being: Antenatal testing (either non‐stress test or biophysical profile) usually indicates non‐reassuring foetal status. Some cases may have low foetal heart rate, absent foetal heart rate variability, or sinusoidal pattern, consistent with foetal blood acidosis.

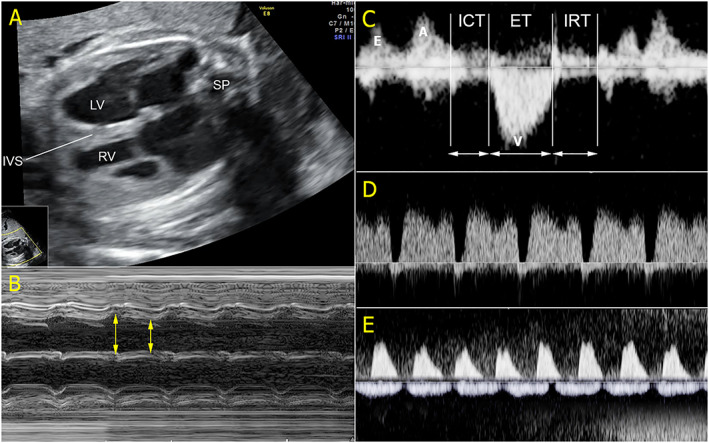

Figure 3.

An example of low‐output hydrops foetalis. (A) The four‐chamber view shows marked cardiomegaly occupying most part of the thoracic cage (IVS, interventricular septum; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; SP, spine); (B) poor contractility or low shortening fraction on M‐mode; (C) myocardial performance index shows prolonged isovolumetric contraction time (ICT) and isovolumetric relaxation time (IRT) together with shortened ejection time (ET); (D) Doppler spectral waveforms of the ductus venosus show reversed flow during atrial contraction; and (E) umbilical artery (UA) and umbilical vein (UV) Doppler waveforms show absent end‐diastolic in UA and venous pulsations in the UV.

In summary, in the low‐output stage, the cardiovascular reserve potentials become exhausted and decompensated. Ultrasound examination reveals abnormally increased Tei index, decreased shortening fraction, increased preload in the ductus venosus and inferior vena cava, decreased cardiac output, and oligohydramnios. Antenatal testing shows non‐reassuring status, and the foetus usually dies in a short time. Heart failure is the final stage of foetal response to anaemia. It is a consequence of longstanding overworked heart when adaptive mechanism becomes exhausted, occurring long after the development of hydrops foetalis.

New challenging insights: a lesson from haemoglobin Bart's disease

At mid‐pregnancy, the affected foetuses have normal cardiac function by clinical assessment; regardless of the presence of hydrops foetalis, there are significant cellular damages of the myocardial cells secondary to anaemic hypoxia. 21

Our extensive experience in Hb Bart's studies indicates that anaemic hydrops foetalis is not caused by heart failure, although heart failure, which is late occurring, can aggravate hydropic changes. Hydrops foetalis is probably caused by hypervolaemia together with high vascular permeability and hypoalbuminaemia, is not associated with poor function, and has no increased central pressure. This is in contrast to the old concept, stating that heart failure causes high central venous pressure and facilitates high interstitial fluid leakage leading to hydrops foetalis. 19 , 20

The foetal heart has very high reserve potentials. The foetuses with untreated anaemia could maintain cardiac function and normal central venous pressure in spite of longstanding marked cardiomegaly, occupying entire thorax for a long time. 4 , 5 , 18

Hydrops foetalis is usually considered to have a poor outcome. However, anaemic hydrops seems to have a better prognosis than cardiac hydrops foetalis. Note that in cases of foetal cardiac defect, hydrops foetalis is a consequence of heart failure, but in anaemic hydrops, the heart usually has a normal function, and the complete recovery can be expected. Accordingly, in anaemic hydrops foetalis secondary to any reversible cause, as long as cardiac function or preload is within normal limit, successful intervention should be expected. This review emphasizes that assessments in foetal anaemia should include not only morphological changes and MCA‐PSV as commonly suggested but also cardiac function and preload in the venous system. 4 , 5 , 18

Importantly, our experiences in foetal blood transfusion in cases of hydrops foetalis secondary to Hb H disease and homozygous Hb Constant Spring disease indicate that even in cases where frank hydropic changes have already occurred but myocardial performance index is still within normal limits, the foetuses can completely recover after intrauterine treatment. 43 , 44 We do not know the point on the timeline of progression at which the foetus can completely recover without residual insults after therapeutic intervention. To the best of our knowledge, most authors suggest intrauterine transfusion in foetuses with Hb deficit >5 g/dL, absolute Hb levels <10 g/L, and haematocrit level <30% in cases of foetal anaemia from reversible causes, such as Rh alloimmunization and parvovirus B19. 1 , 50 However, there is no solid evidence to support such a practice.

Cardiomegaly is the most sensitive marker in clinical response to foetal anaemia among foetuses with Hb Bart's disease. 14 , 17 , 23 , 24 Accordingly, it is reasonable to take cardiomegaly into account for clinical assessment of foetal anaemia secondary to other causes as well, instead of MCA‐PSV alone as used in clinical practice. 1 , 50

During the course of responses to anaemia, from minimal cardiac enlargement to heart failure, some key points on the gestational timeline that clinicians should be aware of are as follows: (i) pre‐hydropic signs; (ii) high‐output hydrops with normal cardiac function; and (iii) hydrops with abnormal venous/cardiac Doppler velocity. Clinicians must clearly specify where on the gestational timeline the foetus is.

Umbilical venous pulsations usually refer to high central venous pressure that is commonly seen in heart failure or a longstanding increase in afterload in foetal growth restriction and is usually considered an ominous sign. 51 However, it is benign and is commonly seen in foetal anaemia caused by dilated ductus venosus secondary to hypervolaemia, not reflective of high central venous pressure. The junction of the ductus and umbilical vein is normally sphincter‐like, preventing the transmission of cardiac pulse to the umbilical vein. 52 , 53 However, in foetal anaemia, the junction is dilated because of hypervolaemia, resulting in loss of the sphincter‐like action and allowing propagation of the pulse to the vein. The important clinical point in differentiating benign venous pulsations from ominous ones is that the former gets along with strong forward flow of a‐wave in the ductus venosus (Figure 2 ), while the latter is associated with absent or reversed a‐waves.

The updated knowledge mentioned earlier may be helpful in clinical practice, although future researches are needed to confirm. According to the old concept that anaemic hydrops foetalis is caused by heart failure, it seems to be hopeless for intrauterine treatment in such cases, but with new insights, hydrops foetalis should warrant comprehensive cardiac assessment to identify the prognosis. The good prognosis may be expected if the cardiac performance is good, in spite of established hydrops, although this needs to be confirmed by further studies. Understandings of foetal adaptive response to anaemia may theoretically be helpful for timely intrauterine treatment. Ideally, intrauterine treatment should be performed as early as possible because cellular damage has already occurred at the time of pre‐hydrops or early hydrops foetalis, although cardiac function is still good. Nevertheless, the role of intrauterine treatment based on this new evidence and how long foetuses can tolerate anaemic hypoxia without residual insults are yet to be explored. However, the evidence suggests that foetuses have very high reserve potentials and the prognosis is likely to be satisfactory if the treatment is performed before development of heart failure, as evidenced by reversal of hydropic process by intrauterine treatment in cases of Hb H‐Constant Spring disease 44 and homozygous Hb Constant Spring. 43

Gap of knowledge

To date, we have learned something about foetal response to anaemia, enabling us to understand where they are on the long way from subtle cardiomegaly to obvious heart failure. However, the most important question that has yet to be clarified is when intrauterine treatment or timely delivery should be performed to prevent irreversible hypoxic insults or foetal heart failure. In practice, foetuses at risk of foetal anaemia such as Rh isoimmunization are recommended to assess foetal anaemia with MCA‐PSV as a non‐invasive screening technique and confirm with cordocentesis in cases of abnormal MCA‐PSV and intrauterine transfusion if foetal haematocrit is of less than 30%. However, such a management is not based on solid evidence. To date, we do not know whether or not myocardial cellular damages (mitochondrial dysfunction, increased ROS levels, and accelerated apoptosis) place the foetuses at higher risk for adult diseases, as foetal programming concept.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This study was funded by the Thailand Research Fund DPG‐6280003 and The Chiang Mai University Research Fund CMU‐2563.

Thammavong, K. , Luewan, S. , Jatavan, P. , and Tongsong, T. (2020) Foetal haemodynamic response to anaemia. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 3473–3482. 10.1002/ehf2.12969.

References

- 1. Abbasi N, Johnson JA, Ryan G. Fetal anemia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017; 50: 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thumasathit B, Nondasuta A, Silpisornkosol S, Lousuebsakul B, Unchalipongse P, Mangkornkanok M. Hydrops fetalis associated with Bart's hemoglobin in northern Thailand. J Pediatr 1968; 73: 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chui DH. α‐Thalassemia: Hb H disease and Hb Barts hydrops fetalis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005; 1054: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luewan S, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Tongsong T. Fetal myocardial performance (Tei) index in fetal hemoglobin Bart's disease. Ultraschall Med 2013; 34: 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luewan S, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Tongsong T. Inferior vena cava Doppler indices in fetuses with hemoglobin Bart's hydrops fetalis. Prenat Diagn 2014; 34: 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sirichotiyakul S, Luewan S, Srisupundit K, Tongprasert F, Tongsong T. Prenatal ultrasound evaluation of fetal Hb Bart's disease among pregnancies at risk at 11 to 14 weeks of gestation. Prenat Diagn 2014; 34: 230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tongsong T, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S. Venous Doppler studies in low‐output and high‐output hydrops fetalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 203: 488–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tongsong T, Wanapirak C, Piyamongkol W, Sirichotiyakul S, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S. Fetal ventricular shortening fraction in hydrops fetalis. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117: 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tongsong T, Wanapirak C, Sirichotiyakul S, Chanprapaph P. Sonographic markers of hemoglobin Bart disease at midpregnancy. J Ultrasound Med 2004; 23: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ko TM, Tseng LH, Hsu PM, Hwa HL, Lee TY, Chuang SM. Ultrasonographic scanning of placental thickness and the prenatal diagnosis of homozygous alpha‐thalassaemia 1 in the second trimester. Prenat Diagn 1995; 15: 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lam YH, Ghosh A, Tang MH, Lee CP, Sin SY. Second‐trimester hydrops fetalis in pregnancies affected by homozygous α‐thalassaemia‐1. Prenat Diagn 1997; 17: 267–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lam YH, Ghosh A, Tang MH, Lee CP, Sin SY. Early ultrasound prediction of pregnancies affected by homozygous α‐thalassaemia‐1. Prenat Diagn 1997; 17: 327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tongsong T, Wanapirak C, Sirichotiyakul S. Placental thickness at mid‐pregnancy as a predictor of Hb Bart's disease. Prenat Diagn 1999; 19: 1027–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tongsong T, Wanapirak C, Sirichotiyakul S, Piyamongkol W, Chanprapaph P. Fetal sonographic cardiothoracic ratio at midpregnancy as a predictor of Hb Bart disease. J Ultrasound Med 1999; 18: 807–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leung KY, Liao C, Li QM, Ma SY, Tang MH, Lee CP, Chan V, Lam YH. A new strategy for prenatal diagnosis of homozygous α0‐thalassemia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006; 28: 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li DZ, Yang YD. Prenatal ultrasound presentations in late pregnancies affected with alpha thalassemia major. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2019; 22: 603–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li X, Zhou Q, Zhang M, Tian X, Zhao Y. Sonographic markers of fetal α‐thalassemia major. J Ultrasound Med 2015; 34: 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luewan S, Srisupundit K, Tongprasert F, Traisrisilp K, Jatavan P, Tongsong T. Z score reference ranges of fetal cardiac output from 12 to 40 weeks of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med 2020; 39: 515–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bellini C, Hennekam RC. Non‐immune hydrops fetalis: a short review of etiology and pathophysiology. Am J Med Genet A 2012; 158A: 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bellini C, Hennekam RC, Fulcheri E, Rutigliani M, Morcaldi G, Boccardo F, Bonioli E. Etiology of nonimmune hydrops fetalis: a systematic review. Am J Med Genet A 2009; 149A: 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jatavan P, Kumfu S, Tongsong T, Chattipakorn N. Fetal cardiac cellular damages caused by anemia in utero in Hb Bart's disease. Curr Mol Med 2020;published online ahead of print; 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lam YH, Tang MH, Lee CP, Tse HY. Prenatal ultrasonographic prediction of homozygous type 1 α‐thalassemia at 12 to 13 weeks of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 180: 148–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leung KY, Cheong KB, Lee CP, Chan V, Lam YH, Tang M. Ultrasonographic prediction of homozygous α0‐thalassemia using placental thickness, fetal cardiothoracic ratio and middle cerebral artery Doppler: alone or in combination? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 35: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li X, Qiu X, Huang H, Zhao Y, Li X, Li M, Tian X. Fetal heart size measurements as new predictors of homozygous α‐thalassemia‐1 in mid‐pregnancy. Congenit Heart Dis 2018; 13: 282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thathan N, Traisrisilp K, Luewan S, Srisupundit K, Tongprasert F, Tongsong T. Screening for hemoglobin Bart's disease among fetuses at risk at mid‐pregnancy using the fetal cardiac diameter to biparietal diameter ratio. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014; 14: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Traisrisilp K, Sirilert S, Tongsong T. The performance of cardio‐biparietal ratio measured by 2D ultrasound in predicting fetal hemoglobin Bart disease during midpregnancy: a pilot study. Prenat Diagn 2019; 39: 647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Siwawong W, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S, Tongsong T. Fetal cardiac circumference derived by spatiotemporal image correlation as a predictor of fetal hemoglobin Bart disease at midpregnancy. J Ultrasound Med 2013; 32: 1483–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tongsong T, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S, Traisrisilp K, Jatavan P. Fetal cardiac remodeling in response to anemia: using hemoglobin Bart's disease as a study model. Ultraschall Med 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghosh A, Tang MH, Lam YH, Fung E, Chan V. Ultrasound measurement of placental thickness to detect pregnancies affected by homozygous α‐thalassaemia‐1. Lancet 1994; 344: 988–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luewan S, Tongprasert F, Piyamongkol W, Wanapirak C, Tongsong T. Fetal liver length measurement at mid‐pregnancy among fetuses at risk as a predictor of hemoglobin Bart's disease. J Perinatol 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Srisupundit K, Tongprasert F, Luewan S, Sirichotiyakul S, Tongsong T. Splenic circumference at midpregnancy as a predictor of hemoglobin Bart's disease among fetuses at risk. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2011; 72: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Srisupundit K, Piyamongkol W, Tongsong T. Identification of fetuses with hemoglobin Bart's disease using middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 33: 694–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tongsong T, Piyamongkol W, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S. Fetal splenic artery peak velocity (SPA‐PSV) at mid‐pregnancy as a predictor of Hb Bart's disease. Ultraschall Med 2011; 32: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamill N, Yeo L, Romero R, Hassan SS, Myers SA, Mittal P, Kusanovic JP, Balasubramaniam M, Chaiworapongsa T, Vaisbuch E, Espinoza J. Fetal cardiac ventricular volume, cardiac output, and ejection fraction determined with 4‐dimensional ultrasound using spatiotemporal image correlation and virtual organ computer‐aided analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 205: 76–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chitkara U, Wilkins I, Lynch L, Mehalek K, Berkowitz RL. The role of sonography in assessing severity of fetal anemia in Rh‐ and Kell‐isoimmunized pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1988; 71: 393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA, Storlazzi E, Mirochnick MH, Escoto DT, Nochimson DJ. Fetal liver ultrasound measurements in isoimmunized pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1986; 68: 162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown BS. The ultrasonographic features of nonimmune hydrops fetalis: a study of 30 successive patients. Can Assoc Radiol J 1986; 37: 164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Graves GR, Baskett TF. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis: antenatal diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984; 148: 563–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tongsong T, Wanapirak C, Srisomboon J, Piyamongkol W, Sirichotiyakul S. Antenatal sonographic features of 100 alpha‐thalassemia hydrops fetalis fetuses. J Clin Ultrasound 1996; 24: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoddick WK, Mahony BS, Callen PW, Filly RA. Placental thickness. J Ultrasound Med 1985; 4: 479–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Apkon M. Pathophysiology of hydrops fetalis. Semin Perinatol 1995; 19: 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Argoti PS, Mari G. Fetal anemia. Minerva Ginecol 2019; 71: 97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sirilert S, Charoenkwan P, Sirichotiyakul S, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S, Tongsong T. Prenatal diagnosis and management of homozygous hemoglobin constant spring disease. J Perinatol 2019; 39: 927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Luewan S, Charoenkwan P, Sirichotiyakul S, Tongsong T. Fetal haemoglobin H‐Constant Spring disease: a role for intrauterine management. Br J Haematol 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sirilert S, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S, Tongsong T. Fetal septum primum excursion (SPE) and septum primum excursion index (SPEI) as sonomarkers of fetal anemia: using hemoglobin Bart's fetuses as a study model. Prenat Diagn 2016; 36: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luewan S, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Tongsong T. Fetal cardiac Doppler indices in fetuses with hemoglobin Bart's disease at 12–14 weeks of gestation. Int J Cardiol 2015; 184: 614–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S, Traisrisilp K, Jatavan P, Tongsong T. Fetal isovolumetric time intervals as a marker of abnormal cardiac function in fetal anemia from homozygous alpha thalassemia‐1 disease. Prenat Diagn 2017; 37: 1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsyvian PB, Markova TV, Mikhailova SV, Hop WC, Wladimiroff JW. Left ventricular isovolumic relaxation and renin‐angiotensin system in the growth restricted fetus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008; 140: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tongsong T, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Luewan S, Traisrisilp K. Ventricular diastolic function in normal fetuses and fetuses with Hb Bart's disease assessed by color M‐mode propagation velocity using cardio‐STIC‐M (spatio‐temporal image correlation M‐mode). Ultraschall Med 2016; 37: 492–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Prefumo F, Fichera A, Fratelli N, Sartori E. Fetal anemia: diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 58: 2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Turan OM, Turan S, Gungor S, Berg C, Moyano D, Gembruch U, Nicolaides KH, Harman CR, Baschat AA. Progression of Doppler abnormalities in intrauterine growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008; 32: 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gennser G. Fetal ductus venosus and its sphincter mechanism. Lancet 1992; 339: 132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kiserud T, Eik‐Nes SH, Blaas HG, Hellevik LR. Ultrasonographic velocimetry of the fetal ductus venosus. Lancet 1991; 338: 1412–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]