Abstract

A novel HIV-1 inhibitor, 6-(tert-butyl)-4-phenyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)-1H,3H-1,3,5-triazin-2-one (compound 1), was identified from a compound library screened for the ability to inhibit HIV-1 replication. EC50 values of compound 1 were found to range from 107.9 to 145.4 nm against primary HIV-1 clinical isolates. In in vitro assays, HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) activity was inhibited by compound 1 with an EC50 of 4.3 μm. An assay for resistance to compound 1 selected a variant of HIV-1 with a RT mutation (RTL100I); this frequently identified mutation confers mild resistance to non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs). A recombinant HIV-1 bearing RTL100I exhibited a 41-fold greater resistance to compound 1 than the wild-type virus. Compound 1 was also effective against HIV-1 with RTK103N, one of the major mutations that confers substantial resistance to NNRTIs. Computer-assisted docking simulations indicated that compound 1 binds to the RT NNRTI binding pocket in a manner similar to that of efavirenz; however, the putative compound 1 binding site is located further from RTK103 than that of efavirenz. Compound 1 is a novel NNRTI with a unique drug-resistance profile.

Keywords: antiviral agents, drug resistance, HIV-1, NNRTI, reverse transcriptase, triazinones

Introduction

The life expectancy of individuals infected with HIV-1 has increased as a result of the combined administration of antiretroviral drugs. However, long-term toxicity and the emergence of drug-resistant viruses remain serious problems.[1,2] To improve the quality of life of individuals infected with HIV-1, novel antiretroviral drugs need to be developed that have no long-term toxicity, low likelihood for drug resistance, and potency against HIV-1 variants that are resistant to pre-existing antiretroviral drugs.[3-5] The development of novel antiretroviral drugs can be achieved through the identification of novel lead compounds, improvements in the potency of current antiretroviral drugs, and searches for novel molecular targets.

To identify potential lead compounds for novel antiretroviral drugs, we screened a commercially available library of structurally divergent, low-molecular-weight compounds. Previously, we used a yeast two-hybrid assay to identify a lead compound [2-(benzothiazol-2-ylmethylthio)-4-methylpyrimidine (BMMP)] that affects Gag–Gag interactions.[6] BMMP was found to inhibit the assembly of the viral capsid protein and to accelerate the disassembly of HIV-1 cores. We also screened compounds for inhibition of RNase H activity, which is associated with HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT), and identified 5-nitrofuran-2-carboxylic acid carbamoylmethyl ester (NACME).[7]

Mammalian-cell-based assays have an advantage over in vitro screens because they can identify toxic substances. We previously screened for non-cytotoxic HIV-1 inhibitors among the library of low-molecular-weight compounds using an assay for HIV-1 replication in a CD4-positive human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-transformed cell line, MT-2. This cell line supports robust HIV-1 replication, leading to a massive cytopathic effect (CPE) within a few days post-infection. Observation of virus-infected cells by microscopy enabled the identification of compounds that inhibit CPE formation, but that do not affect cell viability. The number of primary hits was three out of a library of 20000 compounds (0.0015% hit rate), which is lower than the number obtained by yeast cell-based screening (10 out of 20000) or through in vitro screening for RNase H inhibitors (17 out of 20000). There was no overlap among the primary hits in each screen. Herein we describe the detailed analysis of the most potent compound identified by the mammalian-cell-based assay, 6-(tert-butyl)-4-phenyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)-1H,3H-1,3,5-triazin-2-one (compound 1).

Results and Discussion

Screening of a chemical library for HIV-1 inhibitors

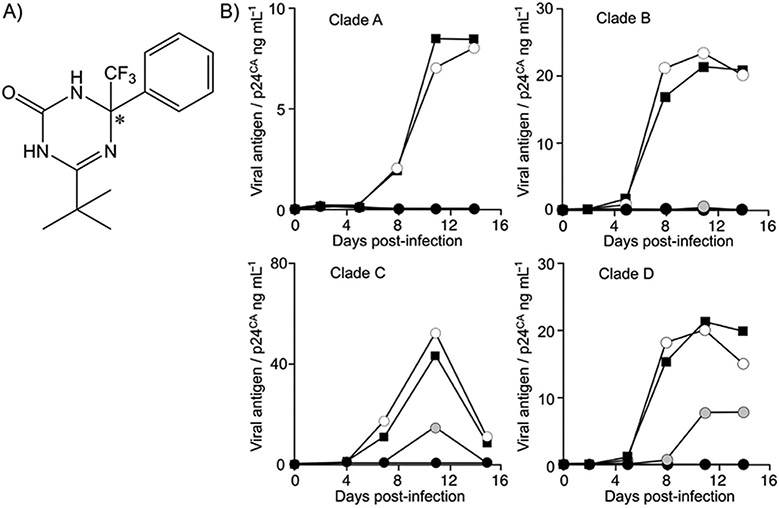

A cell-based screen for anti-HIV-1 activity was performed using MT-2 T-cells infected with HIV-1HXB2. In each assay, infected cells were treated with a pool of five low-molecular-weight compounds covering diverse chemical structures: each compound was used at a concentration of 5 μm. At 3–5 days post-infection, cell viability and virus-induced CPE were assessed by microscopy. Three candidates were selected in the first screen. In the second screen, individual compounds were examined in the same experimental setup, each at a concentration of 5 μm. One of these compounds repeatedly inhibited the formation of HIV-1-induced CPE and exhibited no apparent cytotoxicity. This substance (compound 1) was 6-(tert-butyl)-4-phenyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)-1H,3H-1,3,5-triazin-2-one (C14H16F3N3O, Mr=299.3 Da; Figure 1A). Compound 1 has chirality at the 4-position of the triazinone, to which a trifluoromethyl group was attached, and is thus predicted to be a racemic mixture of enantiomers.

Figure 1.

Structure and biological function of compound 1: A) Chemical structure of compound 1; the asterisk denotes the chiral carbon atom. Compound 1 studied herein is predicted to be a racemic mixture. B) Inhibition of HIV-1 primary clinical isolates of clade A H1144, clade B BaL, clade C MW965, and clade D 74412M1 strains in the PBMC culture by compound 1 at 40 (○), 200 (●), and 1000 nm (●); DMSO solvent control: ■.

To further characterize the anti-HIV-1 activity of compound 1, EC50 values were assessed in various cell types, including PBMCs and T-cell lines (Table 1). The EC50 value of compound 1 was 125.9±16.4 nm (mean±SD of four independent experiments) with primary HIV-1 clinical isolates and PBMCs (Table 1, Figure 1B). Antiviral effects against various HIV-1 strains representing clades A, B, C, and D were similar. Replication of HIV-1 in PBMCs was suppressed to below the limit of detection by compound 1 at 1 μm. The 50% cytotoxic dose (TD50) was > 10 μm in PBMCs (data not shown). Thus, the selective index (TD50/EC50) was ≥79.4. The antiviral activity of compound 1 was verified by three independent laboratories.

Table 1.

Evaluation of biological and biochemical activities of compound 1 in various assay systems.

| Virus | Cells | EC50 [nm][a] | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replication-competent HIV-1 | |||

| Primary isolate HIV-1H1144 (clade A) | PBMC | 107.9 | N=1 p24CA ELISA |

| Primary isolate HIV-1BaL (clade B) | PBMC | 132.3 | N=1 p24CA ELISA |

| Primary isolate HIV-1MW965 (clade C) | PBMC | 117.9 | N=1 p24CA ELISA |

| Primary isolate HIV-174412M1 (clade D) | PBMC | 145.4 | N=1 p24CA ELISA |

| Molecular clone HIV-1HXB2 | MT-2 | 51.9±51.4 | N=2 p24CA ELISA |

| Molecular clone HIV-1HXB2 | CEM | 282.9±199.1 | N=2 p24CA ELISA |

| Molecular clone mRTI[b] resistant HIV-1 | PBMC | 110.2 | N=1 p24CA ELISA |

| Molecular clone mPI[c] resistant HIV-1 | PBMC | 160.9 | N=1 p24CA ELISA |

| Replication-incompetent HIV-1 | |||

| HIV-1NL4–3ΔEnv/Luc pseudotyped with VSV-G | MT-4 | 46.5 | N=1 luciferase activity |

| Lentiviral vector | various | 143.8±162.4 | N=7 luciferase activity |

| Non-HIV-1 | |||

| MLV vector | various | >2000 | N=7 luciferase activity |

| SIVMAC239ΔNef/Luc | various | >2000 | N=2 luciferase activity |

Values are the mean±SD of N replicates, as indicated.

Multiple reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Multiple protease inhibitor.

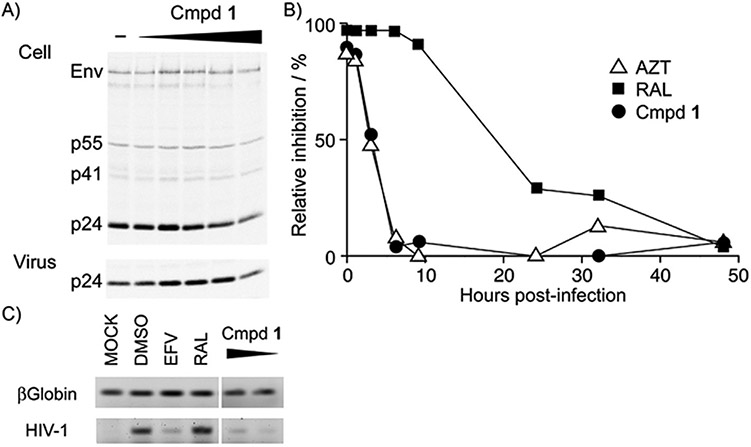

Characterization of the step in the viral replication cycle targeted by compound 1

First, the phase of HIV-1 assembly and release was examined by transfecting the HIV-1 molecular clone pNL4-3 into 293T cells. After transfection, viral gene expression and virus release into the culture medium were examined by radioimmunoprecipitation analysis (Figure 2A). Expression and processing of Gag were not affected by compound 1, and neither was the efficiency of viral release, as assessed by quantitative phosphorimager analysis of Gag levels in cells and viral lysates (data not shown). These data suggested that compound 1 does not target HIV-1 gene expression or particle assembly/release.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the step in the viral replication cycle targeted by compound 1: A) Effect of compound 1 on the late phase of the viral replication cycle. Viral protein expression, processing, and production were examined by radioimmunoprecipitation assay to detect Gag and its cleaved products in the cell lysate and culture supernatant of 293T cells transfected with the proviral clone. Compound 1 concentrations were 1, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μm; DMSO was used as a solvent control. B,C) Effect of compound 1 on the early phase of the viral replication cycle. B) Time-of-addition assay to clarify the effective window of compound 1 activity after viral infection. MT-4 cells were infected with pseudotyped lentiviral vector expressing luciferase, and inhibitors were added at the indicated time points. The inhibitory efficiency was estimated by the percentage of infection signal relative to the DMSO solvent control at each time point; ▵: 500 nm azidothymidine (AZT), ■: 50 nm raltegravir (RAL), ●: 500 nm compound 1. C) PCR analysis to examine reverse transcription of the viral genome in vivo. MT-4 cells were infected with HIV-1 and treated with 200 nm efavirenz (EFV), 200 nm RAL, and 1 μm and 200 nm compound 1. To test the quality of the template DNA, β-globin was amplified. The viral genome that was amplified was the region of reverse transcription initiation.

Next, the early phases of the virus replication cycle were examined with a replication-incompetent pseudotyped HIV-1. The EC50 value of compound 1 was 46.5 nm, as assessed by infection of MT-4 cells with HIV-1NL4–3 bearing a luciferase reporter gene in place of Env (Table 1). Furthermore, a HIV-1-based lentiviral vector that expresses gag-pol only was inhibited by compound 1, with an EC50 of 143.8 nm (Table 1). However, compound 1 did not affect the infection efficiencies of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) or murine leukemia virus. These data suggest that compound 1 targets HIV-1 gag-pol.

To identify the critical time window during which compound 1 inhibits the entry of HIV-1 into target cells, MT-4 cells were infected with a VSV-G-pseudotyped lentiviral vector that expresses luciferase upon infection, and compound 1 was added to the culture medium at various times post-infection. Luciferase activity was then measured three days post-infection (Figure 2B). Compound 1 was effective when added at 1–3 h post-infection, but not when added at 6 h post-infection. The effective time window of compound 1 was similar to that of azidothymidine (AZT), a nucleoside RT inhibitor. A 50% decrease in viral infection was achieved at 2.9 and 3.2 h post-infection by compound 1 and AZT, respectively. By contrast, a 50% decrease in viral infection was achieved at 16.8 h post-infection by the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL). These data suggest that compound 1 acts at an early stage of the viral replication cycle. The fact that the infectivity of a lentiviral vector bearing VSV-G was inhibited suggests that compound 1 acts at a post-entry step.

The kinetics of reverse transcription were assessed by measuring the amount of viral DNA synthesized in HIV-1-infected cells. The early steps of reverse transcription were attenuated by compound 1, as well as by EFV, an NNRTI (Figure 2C). Compound 1 had no inhibitory activity against HIV-1 RT-associated RNase H or multimerization of Gag.[6,7]

Identification of molecular targets of compound 1

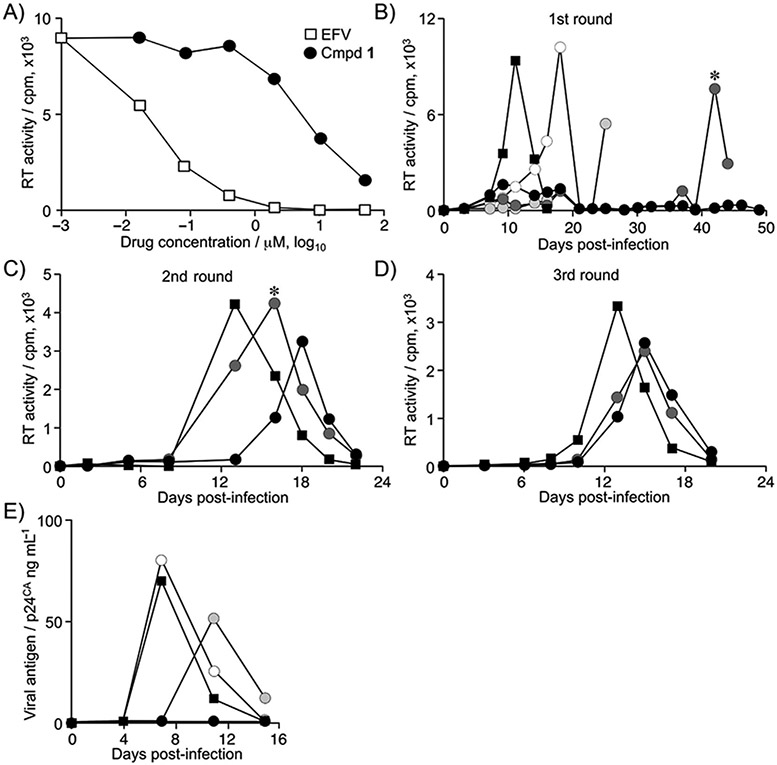

The inhibitory activity of compound 1 on the enzymatic activity of HIV-1 RT was examined (Figure 3A). Compound 1 inhibited RT activity with an IC50 value of 4.3 μm in vitro. In the same experimental setting, EFV had an IC50 of 77.5 nm. These data, along with the biological and structural features, suggest that compound 1 is an NNRTI.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the molecular target of compound 1: A) HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in an in vitro biochemical assay, measuring the amount of reverse transcribed products in a fluorescence assay (relative fluorescent units, RFU); □: EFV, ●: compound 1. B–D) Selection of compound-1-resistant HIV-1. HIV-1NL4–3 was passaged in Jurkat cells in the presence of various concentrations of compound 1. Viral replication was monitored by RT activity in the culture supernatant at each time point. Viruses recovered at the time indicated by the asterisk in the first (B) and second (C) passages were used to seed the second (C) and third (D) passages, respectively. Compound 1 concentrations: 100 (○), 250 (●), 500 (●), and 1000 nm (●); DMSO solvent control: ■; cpm: counts per minute. E) Inhibition of multiple non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI)-resistant clones of HIV-1 by compound 1. Compound 1 concentrations: 40 (○), 200 (●), and 1000 nm (●); DMSO solvent control: ■.

To further confirm the inhibitory effects, HIV-1NL4–3 was passaged in the presence of compound 1 to select for drug-resistant virus in the Jurkat T-cell line (Figure 3B). Initially, HIV-1 replication was delayed in the presence of compound 1, in a dose-dependent manner. Viral replication was not observed when compound 1 was present at 1 μm. The culture supernatant at the peak of viral replication in the presence of 500 nm compound 1 was passaged (Figure 3B-D). The delayed replication peak in the presence of compound 1 was gradually recovered in the second and third rounds of replication in the presence of compound 1 at 500 nm, and even at 1 μm. Sequence analysis revealed the presence of the RTL100I mutation in the third passage at these concentrations. The RTL100I mutation was observed in two independent cultures, emerging at the end of the second passage and becoming dominant in the third passage. This mutation is associated with an approximate five- and tenfold decrease in the susceptibility to nevirapine and EFV, respectively.[8,9] We generated a molecular clone of HIV-1NL4–3 bearing RTL100I and measured its susceptibility to compound 1. The EC50 of compound 1 against HIV-1 with RTL100I was 43.1±29.1 μm, and the magnitude of drug resistance was 41.0±8.3-fold (mean±SD of three independent experiments). These data support that RT is indeed the molecular target of compound 1.

The inhibitory activity of compound 1 was examined with a multiple RT inhibitor (mRTI)-resistant HIV-1 mutant that had the following mutations in RT: Δ67 + T69G, K70R, L74I, K103N, T215F, and K219Q.[10,11] RTK103N is one of the major NNRTI-resistance mutations and confers 20- and 50-fold increased resistance to EFV and nevirapine, respectively.[8,12,13] Compound 1 inhibited replication of mRTI HIV-1, with an EC50 value of 110.2 nm, which was similar to the EC50 against primary clinical HIV-1 isolates (Figure 3E, Table 1). Compound 1 also inhibited a multiple protease inhibitor (mPI)-resistant HIV-1 mutant with the following mutations in protease: L10R, M46I, L63P, V82T, and I84 V;[14] the EC50 was 160.9 nm. These data suggest that compound 1 is effective against HIV-1 that is resistant to other RTIs, and that its function is distinct from that of EFV or nevirapine.

It is unclear why the IC50 value measured by an in vitro assay is approximately 40-fold higher than those measured by in vivo assays. This difference might be a result of the assay setup, but another possibility is that compound 1 accumulates in the cell cytoplasm, and the local concentration within the cell is higher than in the culture medium. Alternatively, the mechanism of action might not be limited to the inhibition of RT activity. When selecting drug-resistant viruses, we found some mutations in Gag and integrase (IN) proteins in one of two independent cultures, which could explain the discrepancy between the in vitro and in vivo efficacies. Finally, compound 1 is chiral; however, selective synthesis of enantiomers was not available from the supplier, and so the isoform content could have varied from lot to lot, with unpredictable effects.

Structural analysis of the interaction between compound 1 and RT

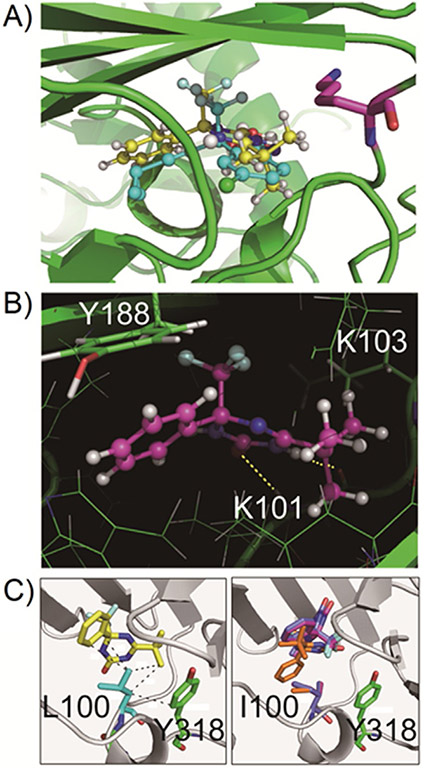

The structural features of compound 1 are similar to those of EFV. We analyzed whether the binding mechanism of compound 1 to HIV-1 RT was also similar to that of EFV, by performing a computer-assisted docking simulation. Initially, the docking of EFV on RT was simulated, and the proposed occupation of the NNRTI binding pocket by EFV was identical to the observation in a crystallographic analysis (Supporting Information Figure S1), providing evidence for the validity of the docking simulation. The ChemScore is an index value representing the molecular fit between RT and compound 1. The docking simulation with compound 1 resulted in its docking to RT in an almost identical manner to that of EFV (Figure 4A). The S enantiomer of compound 1 had a higher ChemScore than the R enantiomer (30.29 vs. 22.49), suggesting that the S enantiomer is responsible for antiviral activity (Supporting Information Table S1). The ChemScore of the interaction between compound 1 and RT was similar to that between EFV and RT (38.80). Notably, the benzoxazinone of EFV and the triazinone of (S)-1 are positioned at almost the same angle to RT, and each functional group of the two compounds stretches out in the same orientation. The amino acid residues of RT that were predicted to interact with compound 1 were L100, K101, K103, Y181, Y188, and G190. The keto group of EFV interacts with the backbone amide group of RTK101 by hydrogen bonding. Similarly, the keto group of (S)-1 interacts with the amine group of the peptide backbone at RTK101 by hydrogen bonding; furthermore, the amine group of compound 1 interacts with the backbone carbonyl group of RTK101 (Figure 4B). The predicted molecular distance between (S)-1 and RTK103 was larger than that between EFV and RTK103. The K103N mutation should cause a clash between the side chain of N103 and EFV, which would obstruct a stable drug–RT interaction. By contrast, compound 1 should be able to bind to RT even with the K103N mutation. When docking was simulated with the RT L100I mutation, the methyl group of I100 interfered with the binding of compound 1 to RT. Accordingly, the ChemScore was greatly affected (Supporting Information Table S1). These predictions were consistent with the available biological data. The side chain of L100 made a CH-π interaction with the phenyl group of compound 1, and also formed a strong hydrophobic interaction with the tert-butyl group of compound 1 (Figure 4C). By contrast, the hydrophobic interaction was disrupted by the L100I mutation because of steric hindrance with the methyl group of I100. This steric hindrance restricts access of compound 1 to the space near Y318.

Figure 4.

Computational analysis of the docking of compound 1 into HIV-1 RT: A) Comparison in binding mode between compound 1 in the simulated structure and EFV in the crystal structure. In ball-and-stick representation, compound 1 is shown in yellow, and EFV is shown in cyan. K103 is denoted by magenta sticks, which is related to the EFV-resistant mutation. B) Magnified view of the binding poses of compound 1 to the polymerase domain of HIV-1 RT. Two critical hydrogen bonds are shown in yellow dashed lines. C) Comparison of the docking pose of compound 1 with wild-type RT (left) and the L100I mutant. Hydrophobic interactions involving L110 are shown by the broken lines in the wild-type enzyme. The top three docking poses in the ranking of ChemScore are superimposed with I110 and Y318 in the L100I mutant. The three poses, in decreasing order of ChemScore, are shown in orange, purple, and blue, respectively.

The computational analysis suggests that the tert-butyl group of compound 1 is slightly large to fit into the NNRTI binding pocket of HIV-1 RT. To improve the potency of this agent, conversion of the tert-butyl group into a less bulky substitute may be effective. Additionally, as compound 1 interacts tightly with RTY181, mutation of Y181 might confer resistance to compound 1. However, the selection of drug-resistant virus did not result in the emergence of Y181 mutations, even though the fitness costs of Y181C/I mutations are lower than that of L100I.[15] This finding suggests the possibility of angle flexibility in the binding of compound 1 to RT, which could contribute to its potential utility in the clinical setting, in which immediate selection of drug-resistant virus is not anticipated.

Analysis of structural analogues of compound 1

To better understand the structure–function relationship of compound 1, we examined ten structural analogues (compounds 2–11, Supporting Information Figure S2). However, none of them showed antiviral activities similar to those of compound 1. The computational simulation revealed that compounds 2, 8, and 11 could be accommodated into the NNRTI binding pocket (Supporting Information Figure S3), probably because their functional groups are relatively small. These compounds yielded lower ChemScores than (S)-1. Compound 8 showed weak anti-HIV-1 activity in the MT-4 Luciferase reporter assay, and had the highest ChemScore among the derivatives, suggesting the reliability of our docking simulation (Supporting Information Table S1). However, the proposed biological activities of structural analogues should be interpreted with caution, because the molar ratios of their enantiomers were not determined.

Conclusions

We describe a novel triazinone derivative that potently inhibits HIV-1 replication by attenuating HIV-1 RT function, in common with other NNRTIs. The unique property of compound 1 is its ability to overcome the major NNRTI-resistance mutation, RTK103N. Compound 1 has synergistic effects against HIV-1 in combination with RT, protease, and fusion inhibitors (Supporting Information Figure S4). Thus, compound 1 could serve as a lead compound for the development of a novel NNRTI to treat patients with HIV-1 infections who fail to respond to current antiretroviral therapy.

Experimental Section

Mammalian cells and transfection:

293T, HeLa, MT-2, and MT-4 cells were provided by the AIDS Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. TZM-bl and Jurkat cells were obtained from the US NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. MT-4 Luc cells were described previously.[16] 293FT cells were purchased from Invitrogen (Tokyo, Japan). Peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs) were isolated and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Japan Bioserum, Fukuyama, Japan), 100 U mL−1 penicillin, 100 mg mL−1 streptomycin (Invitrogen), GlutaMax-I (Invitrogen), insulin-transferrin-selenium A (Invitrogen), 200 ng mL−1 anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (OKT3; Janssen Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), and 70 U mL−1 recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2; Shionogi Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Transfection was carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen).

Chemical compounds:

The chemical library (pre-plated Diversity Set) was purchased from Enamine (Ukraine). Antiretroviral drugs were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

Assessment of antiviral effects:

Molecular clones of HIV-1HXB2 and HIV-1NL4–3, and drug-resistant viral clones, were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Primary isolates of HIV-1 were obtained from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation.[17] HIV-1 replication was monitored by measuring viral p24 capsid antigen in culture supernatant using an ELISA kit, as described previously3.[6] The molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), the lentiviral vector, and the murine leukemia virus vector were described previously.[18,19] The single-round infection assay is described in detail elsewhere.[6] Luciferase activity was measured by the Steady-Glo kit (Promega, Tokyo, Japan). To measure the EC50, the culture was maintained with various concentrations of inhibitors and the parameters of viral infection monitored at 3–11 days post-infection. An RT assay was performed with the EnzChek Reverse Transcriptase Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan). The RT69A enzyme was used as described previously, except that the E. coli strain Rosetta was used and the incubation performed at 37 °C.[20] The dose–response curve was analyzed with the ICEstimator version 2 to estimate IC50 values.[21]

Cytotoxicity:

Cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds was tested with the CellTiter 96 Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay System (Promega), as described previously.[7]

Radioimmunoprecipitation analysis:

Radioimmunoprecipitation assays were performed as described previously.[22] Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with pNL4–3 by means of Lipofectamine 2000. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were starved in Met/Cys-free medium for 30 min and then metabolically labeled with [35S]Met/Cys-Pro mix (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) for 2 h. Cells were treated with compound 1 throughout the transfection and labeling period. Viruses were collected by ultracentrifugation at 75 000 g for 45–60 min. Cell and virus pellets were resuspended in Triton X-100 lysis buffer (300 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mm iodoacetamide, and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets [Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA]), followed by preclearance for 1–2 h and immunoprecipitation with HIV-Ig (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, cat. #3957). Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on gels containing 12% polyacrylamide by SDS-PAGE, dried, exposed to a phosphorimager plate (Fujifilm, Stamford, CT, USA), and quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Selection for resistant mutations:

Virus with resistance against compound 1 was selected using replication-competent HIV-1NL4–3 in Jurkat cells.[23,24] The cells were transfected with pNL4-3 and passaged every 2–3 days in the presence of compound 1 at 100–1000 nm. HIV replication was monitored by RT activity, as previously described.[22] DNA was extracted from pellets of cells that were collected at the peak of replication and the gag-pol region was amplified and sequenced using the following primers: gag region, second-LTR-forward-ao 5’-CAC ACA CAA GGC TAC TTC CCT-3’ and Prots20 5’-TTC TGT CAA TGG CCA TTG TTT AAC-3’; pol region, SK38 5’-ATA ATC CAC CTA TCC CAG TAG GAG AAA T-3’, RT20 5’-CTG CCA GTT CTA GCT CTG CTT C-3’, PR05 5’-AGA CAG GYT AAT TTT TTA GGG A-3’, DRRT6L 5’-TAA TCC CTG CAT AAA TCT GAC TTG C-3’, In-Fout 5’-CAG ACT CAC AAT ATG CAT TAG G-3’, In-Rout 5’-CCT GTA TGC AGA CCC CAA TAT G-3’, In-Fin 5’-CTG GCA TGG GTA CCA GCA CAC AA-3’, and In-Rin 5’-CCT AGT GGG ATG TGT ACT TCT GAA CTT A-3’. Analysis of a drug-resistant molecular clone of HIV-1A molecular clone of HIV-1NL4–3 bearing the RTL100I mutation was generated using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The primers used for this experiment were 5’-GAA TAC CAC ATC CTG CAG GGA TAA AAC AGA AAA AAT CAG TAA C-3’ and 5’-GTT ACT GAT TTT TTC TGT TTT ATC CCT GCA GGA TGT GGT ATT C-3’. The virus was produced in 293T cells. The EC50 of HIV-1NL4–3 bearing RTL100I was determined on TZM-bl cells. Virus (corresponding to 5 ng of p24 capsid antigen) was inoculated for 6 h in the presence of inhibitors onto TZM-bl cells in wells of a 96-well plate and the luciferase assay performed at two days post-infection. The EC50 was calculated with Prism 6 software.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR):

MT-4 cells were infected with a lentiviral vector that had been pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein (VSV-G), and cellular DNA was extracted 6 h post-infection.[18] To amplify the early product of reverse transcription, primers were selected to target the R-U5 region: 5’-CCC GAA CAG GGA CTT GAA AGC-3’ and 5’-CTG CTA GAG ATT TTC CAC ACT GAC-3’. The reaction setup and the primers used to amplify the β-globin sequence were as described previously.)[6]

Docking simulations:

The binding modes of compounds to the nucleotide–polymerase domain of HIV-1 RT were predicted by a docking simulation using GOLD version 5.2.[25] A binding score was also calculated to evaluate the difference in binding affinities between the compounds. The calculation model of RT was extracted from an X-ray crystallographic structure (PDB ID: 1FK9)[26] in which the non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI) efavirenz (EFV) was bound to the polymerase domain. Because several residues were missing from the crystal structure, the whole-body RT model was constructed by homology modeling using Modeller version 9.12,[27] setting 1FK9 as the template. The chemical structures of the compounds used for docking simulation were built in the GaussView version 5 program, then geometry optimization was performed for every compound at the B3LYP/6-31g** level, using Gaussian 09 software, as described previously.[28] In the docking simulation, the search area was restricted to within 30 Å from the Cβ atom of Y188 of the p66 subunit, because EFV binds at Y188 in the 1FK9 crystal structure. An adequate docking space was found in this area for several compounds, including compound 1 and EFV. Ten binding poses were generated, and their binding affinities were estimated by the GoldScore function, enabling the most probable binding pose to be selected. The binding affinity for the selected binding pose was re-estimated using the ChemScore function. This two-step approach was recommended for successful and reliable prediction in docking simulations of low-molecular-weight molecules to target enzymes.[29] In the docking simulation for the RTL100I mutant, the conformation of the side chain of I100 was set to be flexible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (H18-AIDS-Wakate-003 to J.K.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article can be found under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.201600375.

References

- [1].Yazdanpanah Y, Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2009, 4, 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Volberding PA, Deeks SG, Lancet 2010, 376, 49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Emamzadeh-Fard S, Esmaeeli S, Arefi K, Moradbeigi M, Heidari B, Fard SE, Paydary K, Seyedalinaghi S, Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2013, 13, 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Arribas JR, Eron J, Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2013, 8, 341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Solomon DA, Sax PE, Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2015, 10, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Urano E, Kuramochi N, Ichikawa R, Murayama SY, Miyauchi K, Tomoda H, Takebe Y, Nermut M, Komano J, Morikawa Y, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 4251–4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fuji H, Urano E, Futahashi Y, Hamatake M, Tatsumi J, Hoshino T, Morikawa Y, Yamamoto N, Komano J, J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 1380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Melikian GL, Rhee SY, Varghese V, Porter D, White K, Taylor J, Towner W, Troia P, Burack J, Dejesus E, Robbins GK, Razzeca K, Kagan R, Liu TF, Fessel WJ, Israelski D, Shafer RW, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2014, 69, 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].van Westen GJ, Hendriks A, Wegner JK, IJzerman AP, van Vlijmen HW, Bender A, PLoS Comput. Biol 2013, 9, e1002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Imamichi T, Berg SC, Imamichi H, Lopez JC, Metcalf JA, Falloon J, Lane HC, J. Virol 2000, 74, 10958–10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Imamichi T, Sinha T, Imamichi H, Zhang YM, Metcalf JA, Falloon J, Lane HC, J. Virol 2000, 74, 1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shafer RW, J. Infect. Dis 2006, 194, S51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Eshleman SH, Jones D, Galovich J, Paxinos EE, Petropoulos CJ, Jackson JB, Parkin N, AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2006, 22, 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Condra JH, Schleif WA, Blahy OM, Gabryelski LJ, Graham DJ, Quintero JC, Rhodes A, Robbins HL, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Titus D, Yang T, Tepplert H, Squires KE, Deutsch PJ, Emini EA, Nature 1995, 374, 569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kortagere S, Madani N, Mankowski MK, Schon A, Zentner I, Swaminathan G, Princiotto A, Anthony K, Oza A, Sierra LJ, Passic SR, Wang X, Jones DM, Stavale E, Krebs FC, Martin-Garcia J, Freire E, Ptak RG, Sodroski J, Cocklin S, Smith AB III, J. Virol 2012, 86, 8472–8481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Suzuki S, Urano E, Hashimoto C, Tsutsumi H, Nakahara T, Tanaka T, Nakanishi Y, Maddali K, Han Y, Hamatake M, Miyauchi K, Pommier Y, Beutler JA, Sugiura W, Fuji H, Hoshino T, Itotani K, Nomura W, Narumi T, Yamamoto N, Komano JA, Tamamura H, J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 5356–5360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brown BK, Darden JM, Tovanabutra S, Oblander T, Frost J, Sander sBuell E, de Souza MS, Birx DL, McCutchan FE, Polonis VR, J. Virol 2005, 79, 6089–6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Komano J, Miyauchi K, Matsuda Z, Yamamoto N, Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 5197–5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Urano E, Aoki T, Futahashi Y, Murakami T, Morikawa Y, Yamamoto N, Komano J, J. Gen. Virol 2008, 89, 3144–3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yanagita H, Urano E, Matsumoto K, Ichikawa R, Takaesu Y, Ogata M, Murakami T, Wu H, Chiba J, Komano J, Hoshino H, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2011, 19, 816–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Le Nagard H, Vincent C, Mentre F, Le Bras J, Comput. Methods Programs Biomed 2011, 104, 10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Waheed AA, Ono A, Freed EO, Methods Mol. Biol 2009, 485, 163–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Adamson CS, Ablan SD, Boeras I, Goila-Gaur R, Soheilian F, Nagashima K, Li F, Salzwedel K, Sakalian M, Wild CT, Freed EO, J. Virol 2006, 80, 10957–10971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Keren-Kaplan T, Attali I, Estrin M, Kuo LS, Farkash E, Jerabek-Willemsen M, Blutraich N, Artzi S, Peri A, Freed EO, Wolfson HJ, Prag G, EMBO J. 2013, 32, 538–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hartshorn MJ, Verdonk ML, Chessari G, Brewerton SC, Mooij WT, Mortenson PN, Murray CW, J. Med. Chem 2007, 50, 726–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ren J, Stammers DK, Virus Res. 2008, 134, 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fiser A, Do RK, Sali A, Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 1753–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yuki H, Honma T, Hata M, Hoshino T, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2012, 20, 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Verdonk ML, Cole JC, Hartshorn MJ, Murray CW, Taylor RD, Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf 2003, 52, 609–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.