Abstract

Aims

We sought to conduct a meta‐analysis regarding the safety and efficacy of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in patients with heart failure (HF).

Methods and results

MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched from their inception to November 2020 for placebo‐controlled randomized controlled trials of SGLT2 inhibitors. Randomized controlled trials were selected if they reported at least one of the prespecified outcomes in patients with HF. Hazard ratios (HRs) or risk ratios and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were pooled using a random‐effects model. A total of seven trials including 16 820 HF patients (N = 8884 in the SGLT2 inhibitor arms; N = 7936 in the placebo arms) were included. In the overall HF cohort, SGLT2 inhibitors compared with placebo significantly reduced the risk of the composite endpoint of first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death [HR: 0.77 (0.72–0.83); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%], time to first HF hospitalization [HR: 0.71 (0.64–0.78); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0], cardiovascular mortality [HR: 0.87 (0.79–0.96); P = 0.005; I 2 = 0%], and all‐cause mortality [HR: 0.89 (0.82–0.96); P = 0.004; I 2 = 0%]. Results remained consistent across HF‐specific trials and according to diabetes mellitus status. A trend towards benefit was observed in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction for the composite of HF hospitalization and cardiovascular death [HR: 0.80 (0.63–1.00); P = 0.05; I 2 = 29%]. No increased risk of hypovolaemia, hyperkalaemia, and hypotension was seen with SGLT2 inhibitors compared with placebo.

Conclusions

SGLT2 inhibitors significantly improve cardiovascular outcomes including cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality in patients with HF without an increased risk of serious adverse events. A trend towards benefit was observed in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction.

Introduction

Sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have emerged as a new foundational therapy in patients with heart failure (HF) and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). 1 Large‐scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of SGLT2 inhibitors have shown significant cardiovascular and renal benefit across various subgroups. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Three RCTs have specifically assessed the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in the HF population. The DAPA‐HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse‐Outcomes in Heart Failure) trial and EMPEROR‐Reduced (EMPagliflozin outcomE tRial in Patients With chrOnic heaRt Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction) trial evaluated the effects of dapagliflozin and empagliflozin, respectively, in patients with HFrEF. 6 , 7 The recently published SOLOIST‐WHF (Effect of Sotagliflozin on Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Post Worsening Heart Failure) trial studied the effects of sotagliflozin (a combined SGLT2/SGLT1 inhibitor) in a population comprising both patients with HFrEF and patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). 8 All three trials found a significant reduction in the composite endpoint of first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. These results are congruent with data from HF subgroups of cardiovascular outcomes amongst patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM).

SGLT2 inhibitor trials were not powered to study cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality. Moreover, previous meta‐analyses of SGLT2 inhibitors have not specifically focused on patients with prevalent HF across all trials, and none of the studies have included results from the recently published SOLOIST‐WHF trial. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Herein, we present an updated comprehensive meta‐analysis of SGLT2 inhibitors in HF patients, stratified by HFrEF and HFpEF.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

This meta‐analysis was conducted and reported in conformity with the Cochrane and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta‐Analyses) guidelines. 14 , 15 An electronic search of the MEDLINE, Scopus, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases was conducted from their inception up until 18 November 2020. No language restrictions were set. The following keywords and their MeSH terms were used for the search: ‘(sodium‐glucose co‐transporter inhibitor OR SGLT2 inhibitor OR SGLT‐2 inhibitor OR SGLT 2 inhibitor OR tofogliflozin OR sotagliflozin OR empagliflozin OR canagliflozin OR dapagliflozin OR ertugliflozin OR luseugliflozin OR ipragliflozin OR remogliflozin OR sergliflozin) AND (heart failure or cardiac failure OR CHF)’. The detailed search strategy for each database is presented in the Supporting Information, Table S1 . We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov for completed RCTs using pharmaceutical, generic, and trade names of all SGLT2 inhibitors. Reference lists of included trials were manually screened to identify any relevant studies that may have been missed during the search.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Articles retrieved from the systematic search were exported to EndNote Reference Library software, and duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were first screened on the basis of title and abstract, after which the full text was reviewed to assess relevance. Screening of articles was conducted independently by two reviewers (M. S. U. and M. S. K.). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion till consensus. Articles were selected for inclusion if they met all the following prespecified eligibility criteria: (i) compared SGLT2 inhibitors with placebo; (ii) included HF patients; (ii) were either RCTs or post hoc analyses of RCTs; and (iv) reported at least one of the predefined outcomes of interest.

Outcomes of interest, data extraction, and quality assessment

The main outcome of interest was the composite of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. Other outcomes of interest were (i) composite of total (first and recurrent) HF hospitalization and cardiovascular death; (ii) first HF hospitalization; (iii) cardiovascular death; (iv) all‐cause death; and (v) a composite renal endpoint, which was defined as a >40% sustained decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate, end‐stage renal disease, or renal death. The proportion of total serious adverse events and serious adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation were also evaluated. Incidence of the following specific adverse events was also studied: volume depletion, hyperkalaemia, hypotension, major hypoglycaemia, amputations, bone fractures, acute kidney injury, and urinary tract infections. Study characteristics, baseline demographics, outcome data, and safety data were extracted onto a predesigned Excel spreadsheet. Quality assessment of included RCTs was conducted using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. 16 Data extraction and quality assessment were conducted independently by two reviewers (M. S. U. and M. S. K.), and discrepancies were resolved via discussion.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager (Version 5.3, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used for all statistical analyses. For time‐to‐event clinical outcomes, hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals from each trial were extracted. These were transformed to Ln(HR) and standard errors and pooled using a random‐effects model. Standard errors were calculated using the formula outlined in the Cochrane handbook section 7.7.7.2. 15 Instead of HRs, rate ratios were used for recurrent outcomes. For adverse events, raw data were used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals, which were then meta‐analysed using a random‐effects model. A random‐effects model was selected to account for expected heterogeneity in study design, study drug and dosage, and certain outcome definitions. 17 Study weights were assigned using an inverse variance method. As post hoc subgroup analyses of HF patients from cardiovascular and kidney outcome trials are likely to have lower power, less rigorous HF adjudication, and more risk of bias than trials designed specifically to study HF patients; HF‐specific trials were also analysed separately.

The overall HF population included patients with HFrEF and HFpEF and patients with unknown type of HF. If results were reported by HF subtype, the HFrEF and HFpEF populations were analysed separately as well. For the overall HF cohort and HFrEF cohort, subgroup analysis based on DM status was performed for all outcomes. For the DAPA‐HF and EMPEROR‐Reduced trials, data of diabetes subgroups were taken from post hoc studies. 18 , 19 Subgroup analyses based on age, sex, and angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor use were conducted only for the HFrEF population, as data for these subgroups were only available for this population. The χ 2 test was used to test for subgroup differences. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using the Higgins I 2 statistic. 20 Publication bias could not be evaluated visually in funnel plots as less than 10 studies were identified. A P‐value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search results, study characteristics, and baseline demographics

The PRISMA flow chart (Supporting Information, Figure S1 ) summarizes the search and study selection process. Data from seven RCTs evaluating SGLT2 inhibitors were included. This included three HF‐specific trials (DAPA‐HF, EMPEROR‐Reduced, and SOLOIST‐WHF) 6 , 7 , 8 and four cardiovascular outcome trials: CANVAS (CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study), 3 EMPA‐REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients), 4 DECLARE‐TIMI 58 (Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events), 5 and VERTIS‐CV (eValuation of ERTugliflozin effIcacy and Safety CardioVascular outcomes trial). 21 HF patient data from the cardiovascular outcome trials were available from published post hoc studies. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Although the recently published SCORED (Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Moderate Renal Impairment Who Are at Cardiovascular Risk) trial did not report outcome data of patients with baseline HF separately, 26 the authors of this trial presented a pooled analysis of the SOLOIST‐WHF and SCORED trials at the American Heart Association 2020 conference. Whenever possible, the pooled findings from these trials were used in our analysis.

The overall study population in this meta‐analysis included 16 820 HF patients (n = 8884 in the SGLT2 inhibitor arms; n = 7936 in the placebo arms). The HFrEF subpopulation composed of 11 381 patients (n = 5750 in the SGLT2 arms; n = 5631 in the placebo arms). The HFpEF subpopulation composed of 2554 patients (n = 1447 in the SGLT2 arm; n = 1107 in the placebo arm). The rest of the patients had unknown type of HF. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the included studies. The CANVAS, EMPA‐REG OUTCOME, DECLARE‐TIMI 58, VERTIS‐CV, and SOLOIST‐WHF trials included only DM patients. The DAPA‐HF and EMPEROR‐Reduced trials included both DM and non‐DM patients. DAPA‐HF and EMPEROR‐Reduced included only HFrEF patients, while all other trials included both HFrEF patients and HFpEF patients. Three trials (SOLOIST‐WHF, VERTIS‐CV, and DECLARE‐TIMI 58) reported data of patients with HFpEF separately. In VERTIS‐CV and DECLARE‐TIMI 58, an ejection fraction >45% with known HF was considered as HFpEF, while in SOLOIST‐WHF, an ejection fraction >50% was considered HFpEF. All included trials were at low risk of bias (Supporting Information, Table S2 ). Although the SOLOIST‐WHF trial was stopped prematurely due to loss of funding, this is unlikely to be a major source of bias. In this trial, investigator‐reported events (not adjudicated events) were reported, which may have some risk of bias.

Table 1.

Study and baseline characteristics

| EMPEROR‐Reduced | DAPA‐HF | CANVAS | SOLOIST‐WHF | VERTIS‐CV | EMPA‐REG OUTCOME | DECLARE‐TIMI 58 a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empa | Plac | Dapa | Plac | Cana | Plac | Sota | Plac | Ertu | Plac | Empa | Plac | Dapa | Plac | |

| Number of participants | 1863 | 1867 | 2373 | 2371 | 803 | 658 | 608 | 614 | 1286 | 672 | 462 | 244 | 852 | 872 |

| Age, years (SD) | 67.2 (10.8) | 66.5 (11.2) | 66.2 (11.0) | 66.5 (10.8) | 64.1 (8.3) | 63.4 (8.3) | 69 (63–76) | 70 (64–76) | 64.2 (7.9) | 64.7 (7.8) | 64.5 (8.8) | 64.5 (8.9) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Men | 1426 (76.5) | 1411 (75.6) | 1809 (76.2) | 1826 (77.0) | 457 (56.9) | 356 (54.1) | 410 (67.4) | 400 (65.1) | 891 (69.3) | 443 (65.9) | 320 (69.3) | 175 (71.7) | ||

| Women | 437 (23.5) | 456 (24.4) | 564 (23.8) | 545 (23.0) | 346 (43.1) | 302 (45.9) | 198 (32.6) | 214 (34.9) | 395 (30.7) | 229 (34.1) | 142 (30.7) | 69 (28.3) | ||

| NYHA functional classification, % | ||||||||||||||

| II | 75.1 | 75.0 | 67.7 | 67.4 | 62.0 | 67.1 | ||||||||

| III | 24.4 | 24.4 | 31.5 | 31.7 | 5.5 | 3.8 | ||||||||

| IV | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| Mean LVEF, % | 27.7 (6.0) | 27.2 (6.1) | 31.2 (6.7) | 30.9 (6.9) | 35 (28–47) | 35 (28–45) | ||||||||

| HFpEF, % | 127 (20.9) | 129 (21.0) | 680 (52.9) | 327 (48.6) | 399 (46.8) | 409 (46.9) | ||||||||

| HFrEF, % | 481 (79.1) | 485 (79.0) | 319 (24.8) | 159 (23.7) | 318 (37.3) | 353 (40.4) | ||||||||

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 1887 (1077–3429) | 1926 (1153–3525) | 1428 (857–2655) | 1446 (857–2641) | 1817 (845–3659) | 1741 (843–3582) | ||||||||

| Hospitalization for heart failure | 577 (31.0) | 574 (30.7) | 1124 (47.4) | 1127 (47.5) | ||||||||||

| Diabetes b | 927 (49.8) | 929 (49.8) | 1075 (45.3) | 1064 (44.9) | 803 (100%) | 658 (100%) | 25 (4.1) | 20 (3.3) | 1286 (100) | 672 (100) | 462 (100) | 244 (100) | ||

| Duration of diabetes, years | 11.9 (7.9) | 12.2 (7.7) | 11.9 (8.0) | 12.3 (7.8) | ||||||||||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 d | 61.8 (21.7) | 62.2 (21.5) | 66.0 (19.6) | 65.5 (19.3) | 72.7 (19.5) | 73.3 (19.8) | 49.2 (39.5–61.2) | 50.5 (40.5–64.6) | 68.4 (20.2) | 69.3 (20.7) | ||||

| Heart failure medications, n (%) | ||||||||||||||

| ACE inhibitor | 867 (46.5) | 836 (44.8) | 1332 (56.1) | 1329 (56.1) | 680 (84.7) | 572 (86.9) | 254 (41.8) | 241 (39.3) | 1078 (83.8) | 573 (85.3) | 406 (87.9) | 206 (84.4) | ||

| ARB | 451 (24.2) | 457 (24.5) | 675 (28.4) | 632 (26.7) | 245 (40.3) | 270 (44.0) | ||||||||

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 1306 (70.1) | 1355 (72.6) | 1696 (71.5) | 1674 (70.6) | 403 (66.3) | 385 (62.7) | 253 (19.7) | 113 (16.8) | 116 (25.1) | 53 (21.7) | ||||

| ARNI | 340 (18.3) | 387 (20.7) | 250 (10.5) | 258 (10.9) | 93 (15.3) | 112 (18.2) | ||||||||

| ICD or CRT‐D | 578 (31.0%) | 593 (31.8%) | 622 (26.2%) | 620 (26.1%) | ||||||||||

| CRT‐D or CRT‐P | 220 (11.8%) | 222 (11.9%) | 190 (8.0%) | 164 (6.9%) | ||||||||||

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; CRT‐D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; CRT‐P, cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

Data are reported as n (%), mean (SD), or median (interquartile range).

Aggregate baseline data reported of patients with HF on dapagliflozin and placebo regimen.

For SOLOIST‐WHF, within 3 months before randomization. For EMPEROR‐REDUCED and DAPA‐HF, a combination of medical history and pretreated glycated haemoglobin.

For VERTIS‐CV and DECLARE‐TIMI 58, an ejection fraction <45% with known HF was considered as HFrEF; for SOLOIST‐WHF, an ejection fraction <50% was considered HFrEF.

Determined by Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula.

Results for the overall heart failure cohort

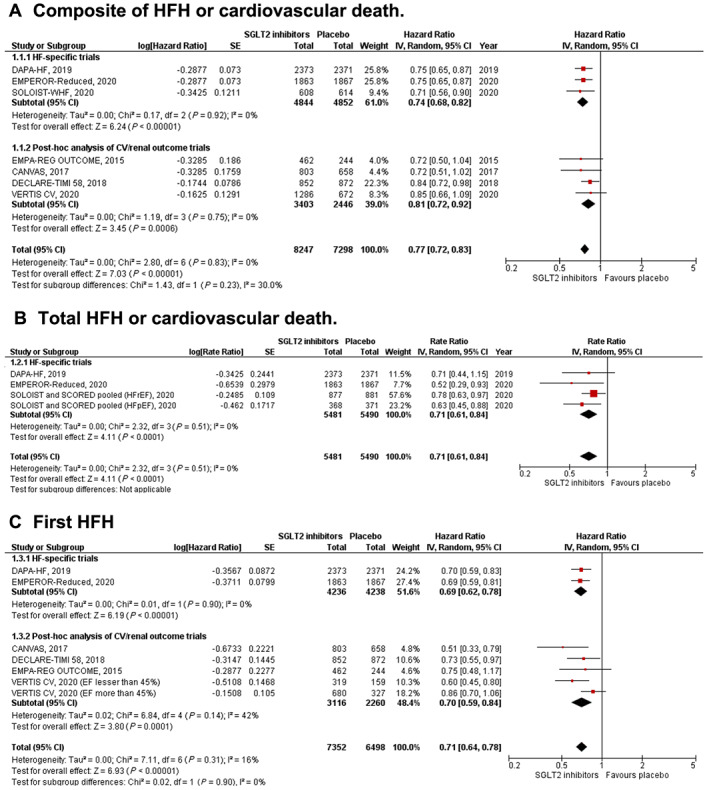

First heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death (Figure 1 A)

Figure 1.

Forest plot displaying the effects of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors vs. placebo in an overall cohort of heart failure (HF) patients, for the following outcomes: (A) composite of first HF hospitalization (HFH) or cardiovascular death; (B) total (first and recurrent) HFH or cardiovascular death; (C) first HFH; (D) cardiovascular death; (E) all‐cause death; and (F) renal composite.

SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the composite of first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death [HR: 0.77 (0.72–0.83); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. The findings from HF‐specific trials and post hoc analyses were consistent (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.23).

Total heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death (Figure 1 B)

SGLT2 inhibitors resulted in a significant reduction in total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death [rate ratio: 0.71 (0.61–0.84); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. This outcome was only reported by HF‐specific trials.

First heart failure hospitalization (Figure 1 C)

SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with a significant reduction in first HF hospitalization [HR: 0.71 (0.64–0.78); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. This finding was seen in both HF‐specific trials and post hoc subgroup studies (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.90).

Cardiovascular death (Figure 1 D)

SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the incidence of cardiovascular death [HR: 0.87 (0.79–0.96); P = 0.005; I 2 = 0%]. The findings were consistent in HF‐specific trials and post hoc studies (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.97).

All‐cause death (Figure 1 E)

SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of all‐cause death in the overall HF cohort compared with placebo [HR: 0.89 (0.82–0.96); P = 0.004; I 2 = 0%]. HF‐specific trials and post hoc studies of cardiovascular trials showed similar results on subgroup analyses (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.44).

Renal composite (Figure 1 F)

The occurrence of the composite renal endpoint was lower with SGLT2 inhibitor use [HR: 0.60 (0.48–0.75); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. This finding was consistent in both HF‐specific trials and post hoc analyses of cardiovascular trials (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.80).

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

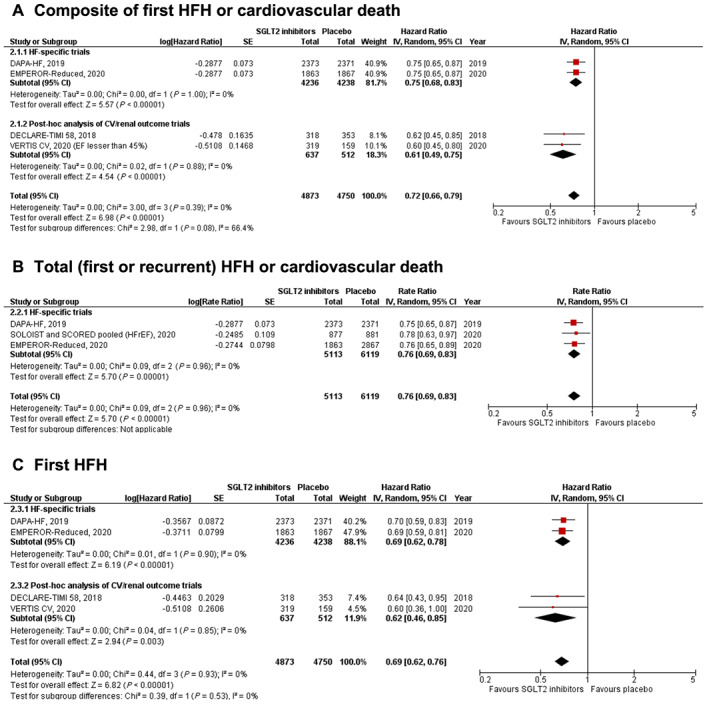

First heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death (Figure 2 A)

Figure 2.

Forest plot displaying the effects of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors vs. placebo in patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction, for the following outcomes: (A) composite of first HF hospitalization (HFH) or cardiovascular death; (B) total (first and recurrent) HFH or cardiovascular death; (C) first HFH; (D) cardiovascular death; (E) all‐cause death; and (F) renal composite.

SGLT2 inhibitors resulted in a significant reduction in the composite of first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death [HR: 0.72 (0.66–0.79); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. The findings from HF‐specific trials and post hoc studies were consistent (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.08).

Total heart failure hospitalizations or cardiovascular death (Figure 2 B)

SGLT2 inhibitors resulted in a significant reduction in total HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death [rate ratio: 0.76 (0.69–0.83); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. This outcome was only reported by HF‐specific trials.

First heart failure hospitalization (Figure 2 C)

SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with a significant reduction in first HF hospitalization [HR: 0.69 (0.62–0.76); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. This finding was seen in both HF‐specific trials and post hoc subgroup studies (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.53).

Cardiovascular death (Figure 2 D)

SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the incidence of cardiovascular death in HFrEF patients [HR: 0.83 (0.71–0.98); P = 0.03; I 2 = 26%]. The findings were consistent in HF‐specific trials and post hoc studies (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.53).

All‐cause death (Figure 2 E)

SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of all‐cause death in the overall HF cohort, when compared with placebo [HR: 0.84 (0.72–0.97); P = 0.02; I 2 = 32%]. HF‐specific trials and post hoc studies of cardiovascular trials were similar for this result (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.48).

Renal composite (Figure 2 F)

The occurrence of the composite renal endpoint was lower with SGLT2 inhibitor use compared with placebo [HR: 0.63 (0.43–0.91); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%]. This finding was only reported by HF‐specific trials.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

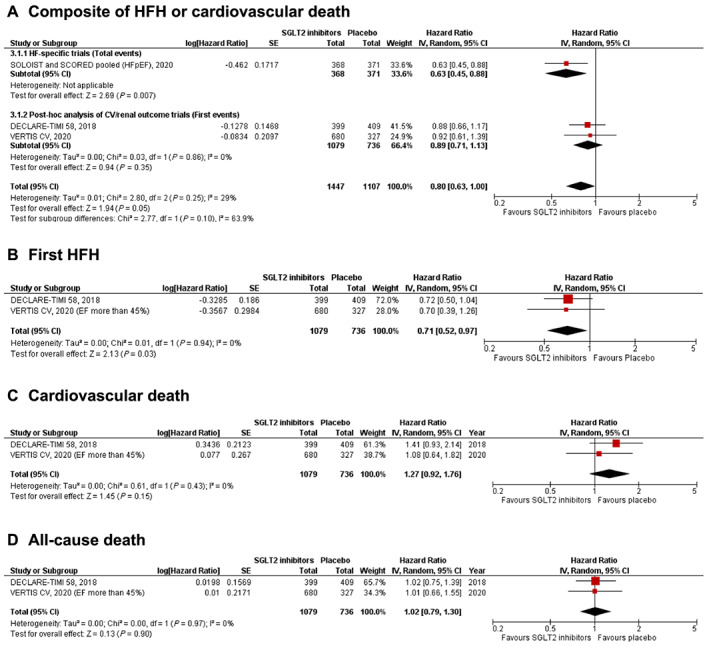

Heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death (Figure 3 A)

Figure 3.

Forest plot displaying the effects of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors vs. placebo in patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction, for the following outcomes: (A) composite of HF hospitalization (HFH) or cardiovascular death; (B) first HFH; (C) cardiovascular death; and (D) all‐cause death.

Data from the DECLARE‐TIMI 58 trial and VERTIS CV trial were combined with pooled data from SOLOIST‐WHF and SCORED trials for this outcome. A borderline significant reduction in the composite of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death was seen with SGLT2 inhibitor use [HR: 0.80 (0.63–1.00); P = 0.05; I 2 = 29%]. However, this analysis was only exploratory, as the outcome reported for the SOLOIST‐WHF and SCORED trials (total HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death) was different from the outcome reported by the other two trials (first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death). Upon sensitivity analysis by excluding SOLOIST‐WHF/SCORED data, the results became non‐significant but continued to trend towards a benefit with SGLT2 inhibitors [HR: 0.89 (0.71–1.13); P = 0.35; I 2 = 0%].

First heart failure hospitalization (Figure 3 B)

This outcome was reported by two post hoc studies from DECLARE‐TIMI 58 and VERTIS‐CV. A significant reduction in first HF hospitalization was seen with SGLT2 inhibitors [HR: 0.71 (0.52–0.97); P = 0.03; I 2 = 0%].

Cardiovascular death (Figure 3 C)

This outcome was reported by two post hoc studies from DECLARE‐TIMI 58 and VERTIS‐CV. There was no significant difference between the SGLT2 inhibitor and placebo groups in the incidence of cardiovascular death amongst HFpEF patients [HR: 1.27 (0.92–1.76); P = 0.15; I 2 = 0%].

All‐cause death Figure 3 D)

This outcome was reported by two post hoc studies from DECLARE‐TIMI 58 and VERTIS‐CV. There was no significant difference between the SGLT2 inhibitor arm and the placebo arm in the incidence of all‐cause death [HR: 1.27 (0.92–1.76); P = 0.15; I 2 = 0%].

Subgroup analysis

The detailed forest plots displaying subgroup analyses are presented in the Supporting Information. For all outcomes in the overall HF population (Supporting Information, Figure S2 ) as well as the HFrEF population (Supporting Information, Figure S3 ), no subgroup effect was seen upon stratification by DM status. Similarly, age (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.55), sex (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.49), and angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor use (P‐value for subgroup differences = 0.52) were not found to modify the treatment effect on the composite endpoint of first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death amongst the HFrEF population.

Safety

In the overall cohort, the incidence of treatment‐emergent serious adverse events [RR: 0.88 (0.84–0.91); P < 0.001; I 2 = 0%] and risk of acute kidney injury [RR: 0.63 (0.45–0.87); P = 0.006; I 2 = 14%] was significantly lower in the SGLT2 inhibitor arm. There was no significant difference between the SGLT2 inhibitor and placebo groups in the rate of discontinuation due to adverse events [RR: 1.07 (0.91–1.25); P = 0.40; I 2 = 0%]. SGLT2 inhibitors did not significantly increase the risk of volume depletion [RR: 1.11 (0.98–1.25); P = 0.11; I 2 = 0%], hypotension [RR: 1.05 (0.84–1.32); P = 0.65; I 2 = 0%], hyperkalaemia [RR: 0.79 (0.49–1.29); P = 0.35; I 2 = 0%], major hypoglycaemia [RR: 1.09 (0.84–1.42); P = 0.53; I 2 = 9%], bone fractures [RR: 1.11 (0.89–1.39); P = 0.36; I 2 = 0%], and urinary tract infections [RR: 1.08 (0.87–1.35); P = 0.48; I 2 = 0%]. SGLT2 inhibitor use was associated with a significant increase in the risk of amputations [RR: 1.57 (1.04–2.35); P = 0.03; I 2 = 0%].

Discussion

In this comprehensive analysis including almost 17 000 HF patients, SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, HF hospitalization, and renal outcomes. These findings remained consistent when the HFrEF population was analysed separately and also when the patients were stratified according to DM status. A trend towards better HF hospitalization‐related outcomes was seen in the HFpEF subpopulation; however, this finding should be considered exploratory rather than definitive due to availability of scarce and heterogeneous data. In comparison with placebo, SGLT2 inhibitors were not found to increase the risk of serious adverse events or discontinuation due to adverse events.

Important differences between the three HF‐specific trials must be kept in mind. The EMPEROR‐Reduced trial enrolled sicker patients with higher N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide concentrations and lower estimated glomerular filtration rate. The SOLOIST‐WHF trial randomized patients with DM and HF irrespective of ejection fraction who were admitted for worsening HF to either sotagliflozin or placebo. 8 Sotagliflozin differs from other SGLT2 inhibitors given its additional SGLT1 inhibiting properties. The remarkable consistency across the three trials for all outcomes evaluated in this meta‐analysis is reassuring, yet more data are necessary for patients with HFpEF. Furthermore, post hoc analyses of cardiovascular trials are also consistent with HF‐specific trials, further reinforcing the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors.

All three HF‐specific trials showed significant reductions in the composite of first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. While DAPA‐HF trial showed a nominally significant reduction in cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality, EMPEROR‐Reduced and SOLOIST‐WHF did not. However, none of these trials were powered to study mortality. Meta‐analysis of these trials demonstrates a significant reduction and cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality. Results from post hoc analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials further support the mortality benefit in HF patients. Our findings also indicate that the mortality benefit persists regardless of DM status.

Unlike HFrEF, the effects of SGLT2 inhibition in HFpEF patients remain unclear. Current evidence with SGLT2 inhibitors, albeit limited, is encouraging. Combined results from the SOLOIST‐WHF and SCORED trials, as well as findings from subgroup analyses of VERTIS‐CV and DECLARE‐TIMI 58, suggest potential reductions in the composite of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. Two ongoing SGLT2 inhibitor trials [EMPEROR‐PRESEVED (EMPagliflozin outcomE tRial in Patients With chrOnic heaRt Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) (NCT03057951) and DELIVER (Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the LIVEs of Patients with PReserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure) (NCT01297257)] will provide further clarity.

There are some limitations in this analysis. The analysis for the HFpEF cohort should only be viewed as exploratory, as this analysis was underpowered, and the data were heterogeneous. In particular, for the composite outcome of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death, recurrent event data from the SOLOIST‐WHF and SCORED trials were pooled with time‐to‐first‐event data from the VERTIS‐CV and DECLARE‐TIMI 58 trials. While these data are distinct, simulations have shown that point estimates for both are usually similar. 27 The definition of HFpEF varied across trials, with VERTIS‐CV and DECLARE‐TIMI 58 using a left ventricular ejection fraction >45% as a cut‐off for HFpEF, while the SOLOIST‐WHF/SCORED trials used a threshold of left ventricular ejection fraction >50%. Due to these differences, a sensitivity analysis by removing SOLOIST‐WHF/SCORED data was also conducted. We did not do a correction for multiplicity of subgroup testing; hence, our subgroup analysis should be considered hypothesis generating. Finally, although a random‐effects model was used to account for methodological heterogeneity, certain differences across studies may limit interpretation. This includes the use of different SGLT2 inhibitor subtypes, varied proportions of men and women, differences in background therapy, baseline risk severity of patients enrolled, and discrepancies in the definition of safety and renal endpoints across trials.

In conclusion, this updated meta‐analysis of ~17 000 HF patients shows that SGLT2 inhibitors significantly decrease HF hospitalizations, adverse renal outcomes, and mortality in patients with HF. These findings remained consistent in patients with HFrEF and in both diabetics and non‐diabetics. Encouraging trend for benefit was observed in patients with HFpEF. Our findings reinforce that all patients with HF, regardless of DM status, may benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors.

Conflict of interest

J.B. is a consultant for Abbott, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squib, CVRx, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Relypsa, and Vifor. S.J.G. was supported by Heart Failure Society of America/Emergency Medicine Foundation Acute Heart Failure Young Investigator Award funded by Novartis, has received research support from Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Novartis, and serves on an advisory board for Amgen. M.V. is supported by the KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst (NIH/NCATS Award UL 1TR002541), serves on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, and Relypsa, and participates on clinical endpoint committees for studies sponsored by Galmed, Novartis, and the NIH. T.F. reports personal fees from Novartis, Bayer, Janssen, SGS, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Galapagos, Penumbra, Parexel, Vifor, BiosenseWebster, CSL Behring, Fresenius Kabi, Coherex Medical, and LivaNova. G.F. participated in committees of trials and registries sponsored by BI, Bayer, Medtronic, Servier, Novartis, and Vifor. A.J.S.C. reports honoraria and/or lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Actimed, Cardiac Dimensions, CVRx, Enopace, Faraday, Gore, Impulse Dynamics, Respicardia, Stealth Peptides, V‐Wave, Corvia, Arena, and ESN Cleer. S.D.A. has received research support from Vifor International & Abbott Vascular and fees for consultancy and/or speaking from Astra‐Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Respicardia, Impulse Dynamics, Janssen, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor International. All other authors report no disclosures.

Supporting information

Table S1. Detailed search strategy for each database.

Table S2. Quality Assessment of included trials.

Figure S1. PRISMA flow chart.

Figure S2. Forest plots displaying subgroup analysis according to DM status in the overall cohort of HF patients for the following outcomes: (A) composite of first HFH or cardiovascular death*; (B) total (first and recurrent) HFH or cardiovascular death; (C) First HFH; (D) cardiovascular death; (E) all‐cause death; (F) Renal composite.

Figure S3. Forest plots displaying subgroup analysis according to DM status in the cohort of HFrEF patients for the following outcomes: (A) composite of first HFH or cardiovascular death*; (B) total (first and recurrent) HFH or cardiovascular death; (C) First HFH; (D) cardiovascular death; (E) all‐cause death; (F) Renal composite.

Butler, J. , Usman, M. S. , Khan, M. S. , Greene, S. J. , Friede, T. , Vaduganathan, M. , Filippatos, G. , Coats, A. J. S. , and Anker, S. D. (2020) Efficacy and safety of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure: systematic review and meta‐analysis. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 3298–3309. 10.1002/ehf2.13169.

Contributor Information

Javed Butler, Email: jbutler4@umc.edu.

Stefan D. Anker, Email: s.anker@cachexia.de.

References

- 1. Tentolouris A, Vlachakis P, Tzeravini E, Eleftheriadou I, Tentolouris N. SGLT2 inhibitors: a review of their antidiabetic and cardioprotective effects. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Usman MS, Siddiqi TJ, Memon MM, Khan MS, Rawasia WF, Talha Ayub M, Sreenivasan J, Golzar Y. Sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018; 25: 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthews DR. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Ruff CT, Gause‐Nilsson IAM, Fredriksson M, Johansson PA, Langkilde AM, Sabatine MS. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Chiang CE, Chopra VK, de Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukát A, Ge J, Howlett JG, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman CEA, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O'Meara E, Petrie MC, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Held C, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Bengtsson O, Sjöstrand M, Langkilde AM. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Kimura K, Schnee J, Zeller C, Cotton D, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure E, Giannetti N, Janssens S, Zhang J, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Kaul S, Brunner‐La Rocca HP, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone S, Pina I, Ponikowski P, Sattar N, Senni M, Seronde MF, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Wanner C, Zannad F. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Lewis JB, Riddle MC, Voors AA, Metra M, Lund LH, Komajda M, Testani JM, Wilcox CS, Ponikowski P, Lopes RD, Verma S, Lapuerta P, Pitt B. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Brueckmann M, Ofstad AP, Pfarr E, Jamal W, Packer M. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta‐analysis of the EMPEROR‐Reduced and DAPA‐HF trials. Lancet 2020; 396: 819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamani N, Usman MS, Akhtar T, Fatima K, Asmi N, Khan MS. Sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitors for the prevention of heart failure in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020; 27: 667–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, Im K, Goodrich EL, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Sabatine MS. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. The Lancet 2019; 393: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salah HM, Al'Aref SJ, Khan MS, Al‐Hawwas M, Vallurupalli S, Mehta JL, Mounsey JP, Greene SJ, McGuire DK, Lopes RD, Fudim M. Effect of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on cardiovascular and kidney outcomes—systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials. Am Heart J 2021; 232: 10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arnott C, Li Q, Kang A, Neuen BL, Bompoint S, Lam CSP, Rodgers A, Mahaffey KW, Cannon CP, Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B. Sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9: e014908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins JPTGS. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011.

- 16. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed‐effect and random‐effects models for meta‐analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010; 1: 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petrie MC, Verma S, Docherty KF, Inzucchi SE, Anand I, Belohlávek J, Böhm M, Chiang CE, Chopra VK, de Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukát A, Ge J, Howlett J, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman CEA, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O'Meara E, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Sjöstrand M, Solomon SD, Johanson P, Greasley PJ, Boulton D, Bengtsson O, Jhund PS, McMurray JJV. Effect of dapagliflozin on worsening heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure with and without diabetes. JAMA 2020; 323: 1353–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Khan MS, Marx N, Lam CSP, Schnaidt S, Ofstad AP, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Bocchi E, Ponikowski P, Perrone SV, Januzzi JL, Verma S, Böhm M, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Zannad F, Packer M. Effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with heart failure by baseline diabetes status—results from the EMPEROR‐Reduced trial. Circulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo‐Jack S, Mancuso J, Huyck S, Masiukiewicz U, Charbonnel B, Frederich R, Gallo S, Cosentino F, Shih WJ, Gantz I, Terra SG, Cherney DZI, McGuire DK. Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1425–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rådholm K, Figtree G, Perkovic V, Solomon SD, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Barrett TD, Shaw W, Desai M, Matthews DR, Neal B. Canagliflozin and heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from the CANVAS program. Circulation 2018; 138: 458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fitchett D, Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Hantel S, Salsali A, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE. Heart failure outcomes with empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk: results of the EMPA‐REG OUTCOME® trial. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 1526–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, Zelniker TA, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, Kuder J, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Bonaca MP, Ruff CT, Desai AS, Goto S, Johansson PA, Gause‐Nilsson I, Johanson P, Langkilde AM, Raz I, Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD. Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2019; 139: 2528–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cosentino F, Cannon CP, Cherney DZI, Masiukiewicz U, Pratley R, Dagogo Jack S, Frederich R, Charbonnel B, Mancuso J, Shih WJ, Terra SG, Cater NB, Gantz I, McGuire DK. Efficacy of ertugliflozin on heart failure‐related events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: results of the VERTIS CV trial. Circulation 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Pitt B, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Lewis JB, Riddle MC, Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod MN, Cherney DZI, Dwyer JP, Scirica BM, Bailey CJ, Díaz R, Ray KK, Udell JA, Lopes RD, Lapuerta P, Steg PG. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Claggett B, Pocock S, Wei LJ, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Comparison of time‐to‐first event and recurrent‐event methods in randomized clinical trials. Circulation 2018; 138: 570–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Detailed search strategy for each database.

Table S2. Quality Assessment of included trials.

Figure S1. PRISMA flow chart.

Figure S2. Forest plots displaying subgroup analysis according to DM status in the overall cohort of HF patients for the following outcomes: (A) composite of first HFH or cardiovascular death*; (B) total (first and recurrent) HFH or cardiovascular death; (C) First HFH; (D) cardiovascular death; (E) all‐cause death; (F) Renal composite.

Figure S3. Forest plots displaying subgroup analysis according to DM status in the cohort of HFrEF patients for the following outcomes: (A) composite of first HFH or cardiovascular death*; (B) total (first and recurrent) HFH or cardiovascular death; (C) First HFH; (D) cardiovascular death; (E) all‐cause death; (F) Renal composite.