Abstract

Introduction:

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) causes high mortality in humans. No vaccines are approved for use in humans; therefore, a consistent effort to develop safe and effective MERS vaccines is needed.

Areas covered:

This review describes the structure of MERS-CoV and the function of its proteins, summarizes MERS vaccine candidates under preclinical study (based on spike and non-spike structural proteins, inactivated virus, and live-attenuated virus), and highlights potential problems that could prevent these vaccines entering clinical trials. It provides guidance for the development of safe and effective MERS-CoV vaccines.

Expert opinion:

Although many MERS-CoV vaccines have been developed, most remain at the preclinical stage. Some vaccines demonstrate immunogenicity and efficacy in animal models, while others have potential adverse effects or low efficacy against high-dose or divergent virus strains. Novel strategies are needed to design safe and effective MERS vaccines to induce broad-spectrum immune responses and improve protective efficacy against multiple strains of MERS-CoV and MERS-like coronaviruses with pandemic potential. More funds should be invested to move vaccine candidates into human clinical trials.

Keywords: Coronavirus, MERS-CoV, spike protein, structural proteins, non-structural proteins, vaccines, preclinical studies

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to the family of Coronaviridae, and consist of alpha-CoV, beta-CoV, gamma-CoV, and delta-CoV genera [1]. Three highly pathogenic human CoVs have caused significant infections in humans, including severe acute respiratory syndrome CoV (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV (MERS-CoV), and the newly identified SARS-CoV-2 (also known as 2019-nCoV), all of which are affiliated to the genus beta-CoV. But phylogenetically, MERS-CoV is distinctive from SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2: MERS-CoV is a member in lineage C, whereas SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 belong to lineage B, of beta-CoV [2,3]. SARS-CoV was first reported in Guangdong, China, in 2002, leading to global outbreaks in 2003 with about 10% mortality [4], whereas SARS-CoV-2 was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and is causing the current worldwide COVID-19 pandemic with around 3.5% mortality [5,6]. MERS-CoV was first isolated from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia in 2012 [7]. Since then, the virus has been identified in 27 countries. Around 2,494 laboratory-confirmed cases, including 858 associated deaths, have been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), with a global mortality rate of about 34.4% [8]. MERS-CoV caused an outbreak of hospital-associated human infections in South Korea in 2015, with a fatality rate of 20.4% [9,10]. Nevertheless, the majority of MERS cases have been identified in Saudi Arabia, which has the highest mortality rate (37.1%) [8].

MERS-CoV is a zoonotic virus which recognizes dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4, CD26) as its functional receptor [11,12], whereas SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV recognize angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as their respective receptor [13,14]. Increasing evidence shows that similar to SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV also originated from bats; indeed, bats are the natural reservoir [15–19]. Dromedary camels are a potential intermediate host [20,21]. A large number of dromedary camels in the Middle East and Africa are MERS-CoV seropositive or have neutralizing antibodies [22–24]. MERS-CoV may replicate in the upper respiratory tract and lungs of dromedary camels, leading to upper respiratory tract infections [25,26]. MERS-CoV is transmitted frequently among camels [27], increasing the possibility for camel-to-human transmission. Indeed, the transmission of MERS-CoV from camels to humans has been demonstrated in camel workers; persons having direct or indirect contact with infected camels may have a higher risk of MERS-CoV infection [21,28–30]. Human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV has been limited; most cases result from household-based infections or from exposure through health-care facilities [31,32]. MERS is still a global concern because the number of MERS-CoV-infected human and camel cases continues to increase. Currently, no MERS vaccines have been approved for use in humans; therefore, effective and safe vaccines are urgently needed to control MERS-CoV infection in humans. In consideration of the limited human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV and its high prevalence and infection rates in camels, novel camel vaccines also need to be developed or existing vaccines need to deploy to prevent and control MERS-CoV infection in camels, and reduce or block camel-to-human transmission.

In this review, we will introduce briefly the structure and function of MERS-CoV and its associated proteins, describe currently developed MERS vaccines under preclinical evaluation, and illustrate the need for improving the efficacy of existing vaccines and progressing promising vaccine candidates from preclinical studies to clinical trials.

2. Structure of MERS-CoV and function of its related proteins

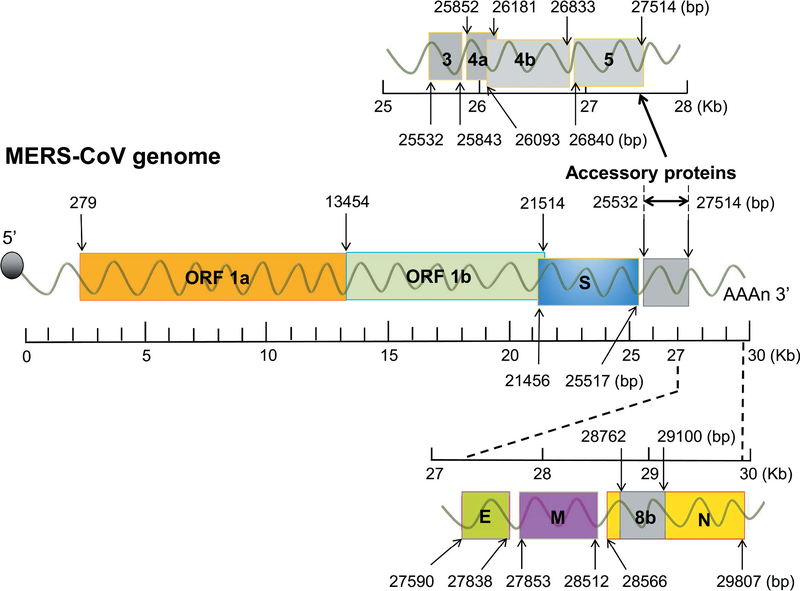

Similar to other CoVs, the MERS-CoV genome contains a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA of about 30,000 nucleotides, which encodes more than 10 open reading frames (ORFs) [33]. The genome encodes four structural proteins (spike (S), nucleocapsid (N), membrane (M), and envelope (E)), 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1–16), which result from ORF 1a- and 1b-translated polyprotein 1a (pp1a) and pp1ab, and five accessory proteins (ORF3, ORF4a, ORF4b, ORF5, and ORF8b) [34] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of MERS-CoV genome and its encoded proteins. The rulers are shown as kilo base pair (Kb). The lengths of ORF 1a/1b, structural proteins (S, N, M, and E), and accessory proteins (3, 4a, 4b, 5 and 8b) are indicated as base pair (bp). E, envelope; M, membrane; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; N, nucleocapsid; ORF 1a and 1b, open reading frame 1a and 1b; S, spike.

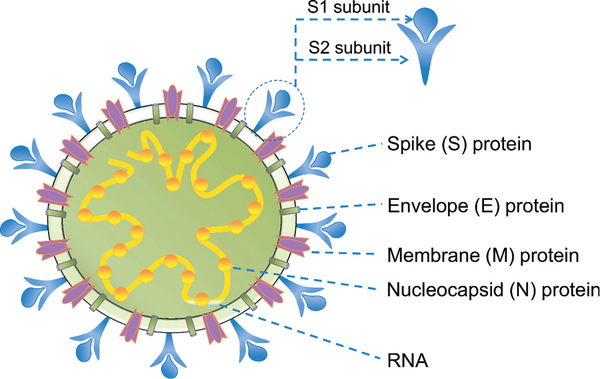

The structure and/or function of the four structural proteins, particularly the S protein, have been studied in detail. Each structural protein plays a role in the formation of virus particles. A schematic diagram of the MERS-CoV structure is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of MERS-CoV structure. MERS-CoV structural proteins (S, N, M, and E) are shown. The S protein, a glycoprotein on the virion surface, consists of S1 and S2 subunits. Viral RNA is located inside the virion.

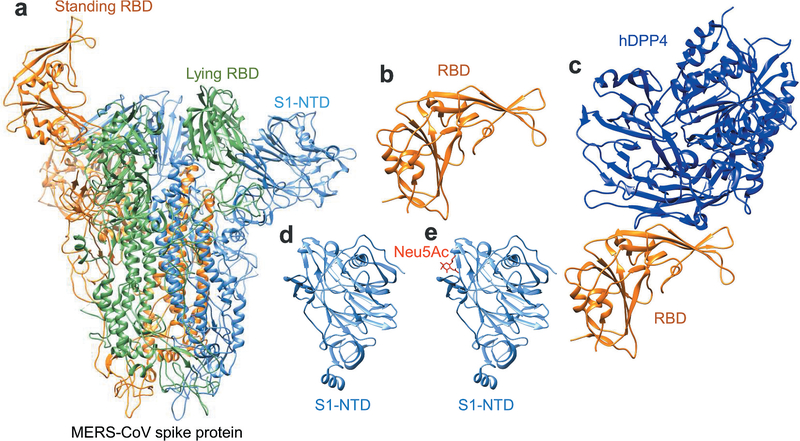

The S protein of MERS-CoV plays the most important role in viral infection and pathogenesis. It extends from the viral membrane, giving the virion a coronal appearance. The S protein mediates the entry of MERS-CoV into target cells. It comprises two subunits: the S1 subunit at the N-terminus and the S2 subunit at the C-terminus [35,36]. The S1 subunit comprises an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD), also known as the receptor-binding domain (RBD) [36,37]. The NTD binds to attachment factors expressing α2, 3-sialic acids [38–40], whereas the CTD (RBD) mediates binding of the virus to the host cellular receptor DPP4 [34,38]. The S2 subunit mediates fusion between the virus and host cell membranes, followed by the release of viral RNA into the target cell [34,41]. MERS-CoV receptor DPP4 is a serine peptidase containing a α/β hydrolytic enzyme domain that can be cleaved into dipeptides [42]. The RBD in MERS-CoV S1 subunit interacts with the β-propeller domain of the DPP4 to form the S-DPP4 complex. Eleven post-lysosomes in the β-propeller domain play a key role in lysing S1/S2 enzyme cleavage sites such that MERS-CoV fuses with the host cell [36,43,44]. MERS-CoV is believed to enter host cells through the mediation by proteases such as transmembrane serine protease, TMPRSS2, on the cell surface or cathepsin L in the endosome [45–47]. Tetraspanin (CD9) forms complexes with the DPP4 receptor and TMPRSS2 to facilitate entry of MERS-CoV [48]. The crystal or cryo-EM structures of the trimeric MERS-CoV S protein, RBD, and RBD-DPP4 complex, as well as those of S1-NTD and its complex with sialoside attachment receptors [36,37,40,49–51], have been solved (Figure 3, made using UCSF Chimera [52]).

Figure 3.

Structures of MERS-CoV S protein and its fragments complexed with viral receptors. (a) Structure of MERS-CoV trimeric S protein. It is presented by ribbon model and colored in orange, green and cornflower blue for each monomer (PDB code 5X5F). One standing RBD (in orange), one lying RBD (in green), and one S1-NTD (in cornflower blue) are labeled separately. (b-c) Structures of MERS-CoV RBD (in orange) and MERS-CoV RBD-hDPP4 complex (RBD in orange and hDPP4 in blue) (PDB code 4KR0) are presented by ribbon model. (d and e) Structures of MERS-CoV S1-NTD and MERS-CoV S1-NTD-Neu5Ac complex are presented by ribbon model (PDB code 6Q04). hDPP4, human dipeptidyl peptidase 4; S1-NTD, N-terminal domain of S1 subunit; RBD, receptor-binding domain; S, spike. UCSF Chimera was used to generate the figures [52].

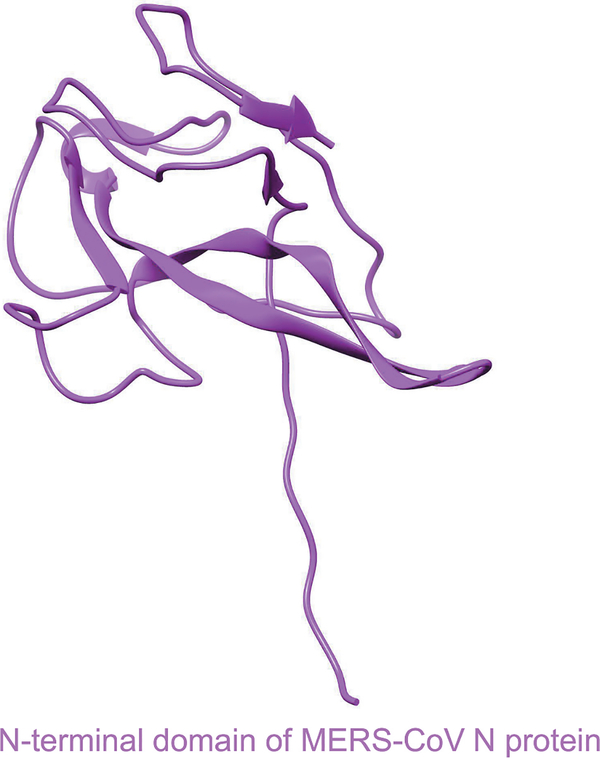

The other three structural proteins (N, M, and E) of MERS-CoV have different functions during the viral life cycle and pathogenesis [34]. For example, the N protein is essential for RNA synthesis, viral replication, virion assembly, and post-translational modification, whereas the M protein interacts with the N protein to play a role in virion assembly [53]. The E protein forms ion channels in lipid bilayers and is associated with virulence; it plays a key role in virion assembly, viral budding, and release [34,53–55]. The crystal structure of the NTD of MERS-CoV N protein has been determined [56,57] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Structure of N-terminal domain (NTD) of MERS-CoV N protein. It is presented by ribbon (PDB code 4UD1). N, nucleocapsid protein. UCSF Chimera was used to generate the figure [52].

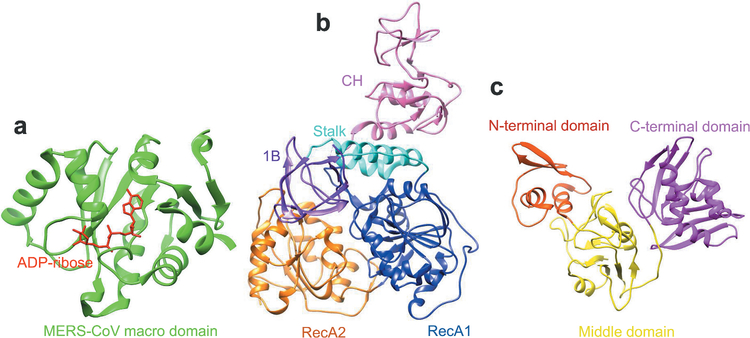

The structure and/or function of several non-structural proteins (nsps) of MERS-CoVs have been identified [48]. For example, the nsp3 protein contains a conserved macro domain that binds efficiently to adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribose [58]. Nsp13 is a helicase with multiple domains [59]. Nsp15 is an endoribonuclease with high affinity for the nsp7/8 complex [60]. Nsp16 is needed for interferon resistance and viral pathogenesis [61]. The crystal structures of MERS-CoV nsp3 macro protein complexed with ADP-ribose, as well as MERS-CoV nsp13 and nsp15 proteins, have been identified [58–60] (Figure 5), providing valuable information and increasing our understanding of the function of these proteins. Generally, the accessory proteins of MERS-CoV antagonize host antiviral responses and are important for helping the virus evade host innate immune responses [55,62], among which ORF 3 to ORF 5 are associated with virulence [63].

Figure 5.

Structures of MERS-CoV non-structural proteins. (A) Structure of MERS-CoV nsp3 macro domain in complex with ADP-ribose. Both MERS-CoV macro domain and ADP-ribose are presented by ribbon model in green and red, separately (PDB code 5DUS). (B) Structure of MERS-CoV nsp13 protein. It is presented in ribbon, which contains CH (pink), stalk (cyan), 1B (purple), RecA1 (blue) and RecA2 (orange) domains (PDB code 5WWP). (C) Structure of MERS-CoV nsp15 protein. It consists of N-terminal domain (orange red), middle domain (yellow), and C-terminal domain (magenta) (PDB code 5YVD). UCSF Chimera was used to generate the figures [52].

3. MERS-CoV vaccine candidates under preclinical development

MERS-CoV continues to infect humans with high fatality rates. A number of vaccines have been developed, which demonstrate immunogenicity and/or efficacy against MERS-CoV infection in available animal models; however, most of these vaccines are at the preclinical development stage. The following paragraphs summarize the candidate MERS vaccines under preclinical investigation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of current MERS vaccines under preclinical developmenta

| Vaccine type | Name | Target | Animals | Immunogenicity and efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical MERS vaccines based on MERS-CoV S protein | |||||

| DNA | MERS pS pS1 pcDNA3.1-S1 |

Full-length S Full-length S S1 S1 |

Mice, camels, or NHPs | Induced MERS-CoV S/S1/RBD-specific Abs, T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against infection of divergent pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV, protecting Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice and NHPs from MERS-CoV challenge | [66,70,71] |

| Viral vector | |||||

| MVA | MVA-MERS-S | Full-length S | Mice or camels | Induced MERS-CoV S/S1-specific Abs, T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against live MERS-CoV infection, protecting Ad-hDPP4-transduced mice and dromedary camels from MERS-CoV challenge; also elicited cross-neutralizing Abs in the immunized camels against MVA viral vector and camelpox virus | [67,73,75,79] |

| Ad (Human) | rAd/Spike rAd/NTD rAd/RBD rAd5-S1/F/CD40L |

Full-length S S-NTD S-RBD S1 |

Mice | Induced MERS-CoV S1-specific Abs (IgG and IgA), T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against infection of pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV, protecting hDPP4-Tg mice from MERS-CoV challenge | [74,81,82] |

| Ad (Chimpanzee) | ChAdOx1 MERS AdC68-S |

Full-length S Full-length S |

Mice or camels | Induced MERS-CoV S1-specific Abs (IgG, IgA), T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against infection of pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV, protecting hDPP4-KI mice and camels from challenge of wildtype and mouse-adapted MERS-CoVs; neutralizing Abs and T-cell responses increased after boost with a MERS MVA vaccine | [83–85] |

| VSV | VSVΔG-MERS | Full-length S | NHPs | Induced MERS-CoV S-specific T-cell response and neutralizing Abs; protective efficacy is unknown | [77] |

| MV | MVvac2-MERS-S MVvac2-MERS-solS |

Full-length S Truncated S |

Mice | Induced MERS-CoV S-specific T-cell response and neutralizing Abs against live MERS-CoV infection, protecting Ad-hDPP4 (ADV-hDPP4)-transduced mice from MERS-CoV challenge; also elicited MV-specific T-cell response and neutralizing Abs against MV virus | [78,87] |

| Subunit | |||||

| Protein | rRBD RBD-Fc RBD-Fd T579N |

S-RBD S-RBD S-RBD S-RBD |

Mice, rabbits, or NHPs | Maintained good antigenicity and functionality to bind MERS-CoV RBD-specific mAbs and hDPP4 receptor; induced MERS-CoV S1/RBD-specific Abs (IgG, IgA), T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against infection of divergent strains of pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV and mAb escape mutants, protecting Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice and hDPP4-Tg mice from high-dose MERS-CoV challenge | [68,90,91,96–98] |

| S1 | S1 | Mice, NHPs, camels, or alpacas | Induced neutralizing antibodies against infection of pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV, conferring complete protection of alpacas and delayed viral shedding in the upper respiratory tract of dromedary camels from MERS-CoV challenge, and reducing MERS-CoV-caused pneumonia in NHPs | [72,92] | |

| MERS S-2P | S-ectodomain | Mice | Induced neutralizing Abs against infection of multiple strains of pseudotyped MERS-CoV | [49] | |

| rNTD | S-NTD | Mice | Induced MERS-CoV S-NTD-specific Abs, T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against infection of pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV, protecting Ad5-DPP4-transduced mice from MERS-CoV challenge | [104] | |

| VLP | sVLP cVLPs |

Full-length S S-RBD S + E + M |

Mice or NHPs | VLPs expressing S/RBD protein induced MERS-CoV S/RBD-specific Abs, T-cell response, and/or neutralizing Abs against pseudotyped MERS-CoV infection; VLPs expressing S, E, and M proteins elicited RBD-specific Abs, T-cell (Th1) response, and neutralizing Abs against live MERS-CoV infection | [64,105,106] |

| BLP | RLP3-GEM | S-RBD | Mice | Induced MERS-CoV RBD-specific Abs (IgG, IgA), T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against pseudotyped MERS-CoV infection | [65] |

| Nanoparticle | MERS-CoV Spike | Full-length S | Mice | Induced MERS-CoV S-specific Abs and neutralizing Abs against live MERS-CoV infection, protecting Ad-hDPP4-transduced mice from MERS-CoV challenge | [69,107,109] |

| Human Ad5 + Nanoparticle | Ad5/MERS + Spike nanoparticle |

Full-length S Full-length S |

Mice | Heterologous prime with Ad5/MERS and boost with S nanoparticles induced MERS-CoV S-specific Abs, T-cell response, and neutralizing Abs against live MERS-CoV infection, protecting Ad5/hDPP4 mice from MERS-CoV challenge | [109] |

| Preclinical MERS vaccines based on MERS-CoV N protein | |||||

| Viral vector | |||||

| MVA | MVA-MERS-N | Full-length N | Mice | Induced MERS-CoV N-specific T-cell (CD8+) response and identified a N-specific T-cell (CD8+) epitope in mice | [110] |

| MV | MVvac2-MERS-N | Full-length N | Mice | Induced MERS-CoV N-specific T-cell response | [78] |

Abs, antibodies; Ad, adenovirus; BLP, bacterium-like particle; E, envelope; hDPP4, human dipeptidyl peptidase 4; hDPP4-KI, hDPP4-knock-in; hDPP4-Tg, human DPP4-transgenic; M, membrane; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV, MERS coronavirus; MV, measles virus; MVA, modified Vaccinia virus Ankara; N, nucleocapsid; NHPs, non-human primates; NTD, N-terminal domain; RBD, receptor-binding domain; S, spike; VLP, virus-like particle; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

3.1. Preclinical MERS-CoV vaccines based on the viral S structural protein

The S protein mediates receptor recognition and viral entry into host cells; thus, it is the primary target for inducing effective immune responses to MERS-CoV infection. Antibodies targeting the S protein play a key role in controlling MERS-CoV; by contrast, S protein-induced cellular immune responses are not necessary to prevent MERS-CoV infection [34,64]. A number of S protein-targeting vaccines are under preclinical development, and are based on MERS-CoV DNA, viral vectors, proteins, virus-like particles (VLPs), bacterium-like particles (BLPs), and nanoparticles [65–69).

3.1.1. DNA vaccines

Several DNA vaccines encoding the MERS-CoV S protein or its S1 fragment have been investigated for immunogenicity and/or protection in animal models such as mice, camels, and non-human primates (NHPs) [66,70–72]. A pcDNA3.1-vectored DNA vaccine encoding the MERS-CoV S1 subunit (pcDNA3.1-S1) induced S-specific antibodies, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immune responses, and neutralizing antibodies in mice, and protected Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice from MERS-CoV challenge with reduced or cleared viral loads in the lung tissues [70]. Although injection of mice with full-length S (pS) or S1-subunit (pS1)-based DNA vaccines expressed in the pcDNA3.1 vector induced S1-specific antibodies with neutralizing activity against human and camel strains of MERS-CoV, only pS1 elicited S1-specific cellular immune responses [71]. Nevertheless, other studies indicate that a synthetic anti-S DNA vaccine (MERS) based on the pVax1 vector and an IgE signal peptide induced S-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, antibody responses, and neutralizing antibodies in mice, camels, and NHPs; indeed, they protected vaccinated NHPs against challenge with MERS-CoV, showing no, or minor, infiltration in the lung [66]. These studies suggest that different vectors and/or signal peptides used to generate DNA vaccines might affect the immunogenicity of DNA-based MERS vaccines.

3.1.2. Viral-vectored vaccines

A variety of viral vectors, including Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA), adenovirus (Ad), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), and measles virus (MV), have been designed based on MERS-CoV S and/or its fragments and subsequently evaluated for immunogenicity and/or protection against MERS-CoV infection in animal models, including mice, camels, and NHPs [67,73–78].

The immunogenicity and protective efficacy induced by a modified MVA expressing MERS-CoV full-length S protein (MVA-MERS-S) have been evaluated in mice and camels [67,73,75,79]. The vaccine induced neutralizing antibodies and CD8+ T cell responses in mice, and protected Ad-hDPP4-transduced mice from infection by MERS-CoV, with reduced level of RNA copies and minimal lesions in the lung tissues [73,75]. The vaccine also elicited mucosal immune responses in dromedary camels, thereby protecting them against MERS-CoV. Camels showed reduced viral titers and viral RNA copy numbers, and protection correlated positively with the titer of serum neutralizing antibodies [67].

Recombinant adenovirus (rAd)-based MERS vaccines expressing full-length S protein, S1, NTD, and RBD have been investigated extensively in preclinical studies [74,80–82]. Among them, human adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) is the most popular Ad vector used to develop MERS vaccines [74,76,81,82]. A rAd5 vector expressing the full-length S protein (rAd/Spike) induced higher titers of neutralizing antibodies and stronger cellular immune responses than a rAd vector expressing NTD (rAd/NTD) or RBD (rAd/RBD); this vaccine also elicited IgA antibodies with neutralizing activity when administered through the intranasal and sublingual routes (not through the intramuscular route), as well as memory CD8+ T cells when administered via the intranasal route [82]. These reports suggest that different lengths of S protein and different immunization routes affect the immunogenicity of Ad5-vectored MERS vaccines. In addition, a single dose of a rAd5 vaccine expressing CD40-targeted S1 protein (rAd5-S1/F/CD40L) induced IgG and neutralizing antibodies at levels similar to those induced by two doses of rAd5-S1 lacking CD40L; also, it completely protected hDPP4-transgenic (hDPP4-Tg) mice against challenge with MERS-CoV, preventing vaccine-associated pulmonary pathology with no evidence of perivascular hemorrhage, which was observed in the same mice immunized with rAd5-S1 [81]. These results suggest that the incorporation of CD40L increases the efficacy of rAd5-based MERS vaccines but without causing immunopathology.

Except for human Ad5, chimpanzee adenoviruses (including AdC68 and ChAdOx1) have been evaluated as viral vectors for MERS vaccines. Administration of a single dose of ChAdOx1 or AdC68 expressing MERS-CoV full-length S protein (ChAdOx1 MERS or AdC68-S) induced serum antibody responses, nasal neutralizing antibodies, and/or cellular immune responses in dromedary camels or mice, thereby protecting camels and hDPP4-knock-in (hDPP4-KI) mice from MERS-CoV infection and infection with mouse-adapted MERS-CoV, with reduced, or undetectable, viral replication [83,84]. Notably, a ChAdOx1 MERS vaccine containing the human tissue plasminogen activator gene (tPA) signal peptide increases the production of neutralizing antibodies in mice to a greater extent than ChAdOx1 MERS without tPA, and a single dose of this vaccine containing tPA-induced antibody responses similar to those induced by two doses of MVA MERS with tPA [85]. In particular, neutralizing antibodies and cellular immune responses elicited by ChAdOx1 MERS-tPA can be boosted by MVA MERS-tPA [85]. These studies suggest that viral vectors and signal peptides may affect the immunogenicity induced by chimpanzee Ad-vectored MERS vaccines.

VSV-vectored MERS vaccines expressing full-length S protein and RBD have been developed and tested for immunogenicity in animal models, including mice and NHPs [77,86]. A MERS-CoV S-expressed VSV vaccine (VSVΔG-MERS) was designed in which the VSV G gene was replaced with the MERS-CoV S gene [77]. A single dose of this vaccine induced neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses in NHPs; nevertheless, its protective efficacy in animal models is unknown. Comparison of the immunogenicity of five different versions of the MERS-CoV S protein and RBD fused to (or not) the transmembrane domain of VSV G protein demonstrated that only full-length S protein and the membrane form of RBD delivered via rAd5 (i.e., rAd5-S, rAd5-S-G, and rAd5-RBD-G) induced anti-MERS-CoV neutralizing antibodies [86]. These studies suggest the possibility of combining S and/or RBD-based VSV vaccines with other viral-vectored vaccines.

MV-based MERS-CoV vaccines expressing MERS-CoV full-length S protein (MVvac2-MERS-S) and truncated S protein, which is a soluble form lacking the transmembrane (MVvac2-MERS-solS), respectively, have been developed [78,87]. The soluble protein variant can be taken up better by B cells and thus induces humoral immune responses more efficiently. MVvac2-MERS-S and MVvac2-MERS-solS induced anti-MERS-CoV neutralizing antibodies in addition to MERS-CoV S-specific cellular immune responses in type I interferon receptor-deficient (IFNAR−/−) CD46Ge mice, thereby protecting mice transduced with the Ad-hDPP4 receptor (ADV-hDPP4) from MERS-CoV challenge, with reduced viral replication in the lung [87]. Notably, these MV-based MERS vaccines also elicited MV-specific neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses, in addition to inducing antibodies targeting MERS-CoV [78,87].

3.1.3. Protein-based vaccines

Protein-based MERS vaccines based on the RBD (i.e., CTD), S1, and full-length S proteins are under preclinical development and most show immunogenicity and/or protection against MERS-CoV infection in animal models such as mice, rabbits, alpacas, camels, and/or NHPs [68,88–92].

Protein-based MERS vaccines targeting the RBD have been studied extensively and are summarized in detail in a previous review article [93]. Administration of an RBD protein containing MERS-CoV S residues 358–588 bound to MERS-CoV receptor DPP4 elicited antibodies that were able to neutralize MERS-CoV infection [94]. In addition, immunization with a recombinant RBD (rRBD) protein (residues 367–606) in combination with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant and cysteine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODN) elicited RBD-specific antibodies and T cell responses in mice, along with low levels of neutralizing antibodies [95]. It also induced robust and sustained immune responses (but provided only partial protection) in rhesus macaques (NHPs), thereby alleviating pneumonia and decreasing viral loads in the lung, trachea, and oropharyngeal swabs [91]. In addition, an RBD fragment comprising residues 377–588 is a critical neutralizing domain, and RBD proteins containing this fragment fused to either the Fc of human IgG (RBD-Fc) or the Foldon (Fd) trimeric motif (RBD-Fd) bound strongly to the DPP4 receptor; in mice and/or rabbits, these fusion proteins elicited potent antibody responses and/or neutralizing activity against divergent strains of MERS-CoV infections from different time periods and hosts (humans and camels) [90,96–99]. Also, a stable CHO-expressed RBD-Fc protein protected hDPP4-Tg mice from MERS-CoV challenge without induction of immunological toxicity or eosinophilic immune enhancement [98]. Moreover, MF59 is an ideal adjuvant that potently increases the ability of the RBD protein to elicit strong antibody responses and high titers of neutralizing antibodies [100]. In particular, the RBD protein, when used at an optimal antigen dose, immunization dose, and immunization interval (two doses at 4-week intervals), elicited high-titer, long-lasting neutralizing antibodies in mice, and protected hDPP4-Tg mice from MERS-CoV infection, preventing lung damage and inflammatory cell infiltration. In addition, this protection was positively associated with the titer of serum neutralizing antibodies [101,102]. Nevertheless, RBD proteins containing wild-type sequences could not provide complete protection (<100% survival rate) of hDPP4-Tg mice against high-dose MERS-CoV infection [97,102,103]. When a glycan probe was introduced into an appropriate position (i.e., the non-neutralizing epitope at residue 579) in the wild-type RBD sequence to generate a mutant RBD protein (T579N), the mutant bound strongly to a number of conformation-dependent neutralizing antibodies and to the DPP4 receptor, thereby eliciting highly potent neutralizing antibody responses that completely (100% survival rate) protected all vaccinated hDPP4-Tg mice against challenge with high-dose MERS-CoV [68]. These studies suggest the importance and potential to design structure-based MERS vaccines with enhanced efficacy by masking the non-neutralizing epitopes and preserving the related neutralizing epitopes.

In addition to the RBD, MERS-CoV S protein and the S1 subunit can serve as additional targets for the development of subunit vaccines against MERS-CoV infection. These proteins also contain the RBD; thus, they can bind to the host receptor DPP4 and mediate MERS-CoV entry into target cells. Several protein-based MERS vaccines have been designed using MERS-CoV S1 and S as antigens. These have been tested preclinically for immunogenicity and/or efficacy [49,72,92]. The ectodomain of both the S protein and S1 subunits can elicit neutralizing antibodies in mice, NHPs, dromedary camels, and/or alpacas, although the immunogenicity and efficacy are different in various animal models [49,72,92]. For example, while adjuvanted MERS-CoV S1 protein confers complete protection from challenge by MERS-CoV in alpacas, it results in decreased and delayed viral shedding in the upper respiratory tract of dromedary camels; the protective efficacy is positively associated with serum neutralizing antibody titers [92]. In addition, two doses of a S1 subunit protein or two doses of a full-length S DNA boosted with one dose of S1 protein elicited neutralizing antibodies in mice and NHPs, which were effective against divergent strains of pseudotyped and live MERS-CoV; these antibodies protected NHPs against MERS-CoV-induced pneumonia [72].

Other fragments of MERS-CoV S protein that have potential as alternative vaccine targets include NTD and S2. The NTD protein induces specific humoral and cellular immune responses, which reduce lung disease symptoms in Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice infected with MERS-CoV [104]. A neutralizing mAb can be generated to target only the S2 subunit [72]. Notably, compared with the full-length S and RBD proteins, these regions generally elicit no, or relatively low-titer, neutralizing antibodies and/or low-level protection against MERS-CoV.

3.1.4. VLP and BLP-based vaccines

Only a few MERS vaccines are based on VLPs and BLPs; several of these express the MERS-CoV full-length S protein or RBD, and some are constructed using the S, E, and M structural proteins [64,105,106]. These candidates have been assessed for immunogenicity in animal models, including mice and NHPs; however, their protective efficacy against MERS-CoV infection has not been evaluated in vivo.

A chimeric VLP generated by fusing the MERS-CoV S protein with the matrix protein 1 (M1) protein of H5N1 influenza virus elicited MERS-CoV S-specific antibodies in mice, which showed neutralizing activity against pseudotyped MERS-CoV [105]. Also, a chimeric, spherical VLP (sVLP) was constructed by fusing the canine parvovirus VP2 structural protein gene to the MERS-CoV RBD [64]. This fusion induced RBD-specific antibodies, cellular immune responses, and neutralizing antibodies in mice, which inhibited entry of pseudotyped MERS-CoV into the target cell [64]. Furthermore, a VLP expressing MERS-CoV S, E, and M proteins conjugated with an aluminum adjuvant elicited T-helper 1 (Th1)-mediated immune responses and RBD-specific antibodies in NHPs, thereby neutralizing infection with live MERS-CoV [106].

A BLP-based MERS-CoV vaccine (RLP3-GEM) has been constructed as an alternative to VLP-based MERS vaccines; the former harbors an RBD linked through three protein anchors (RLP3) and uses gram-positive enhancer matrix (GEM) as a substrate [65]. This vaccine induced antibody, cellular, and mucosal immune responses in immunized mice when adjuvanted with GEL01.

3.1.5. Nanoparticle-based vaccines

Several nanoparticle-based vaccines expressing the MERS-CoV full-length S protein have been designed and generated in insect cells and then evaluated for immunogenicity and/or efficacy in mice [69,107]. Surfactant treatment and mechanical extrusion of insect cells expressing S protein promote the formation of nanovesicles, providing the basis for optimal production of nanoparticle vaccines [108]. A full-length S-expressing nanoparticle generated in the insect cell expression system induced S-specific antibodies with neutralizing activity, particularly when conjugated with Matrix M1 adjuvant, thereby protecting immunized Ad-hDPP4-transduced mice from MERS-CoV infection, with reduced viral replication in the lung [69,107]. It is noted that nanoparticle vaccines can be incorporated into other types of MERS vaccines to improve their immunogenicity. For example, heterologous priming with rAd5 encoding full-length S protein (Ad5/MERS), followed by boosting with full-length S protein nanoparticles formulated with an aluminum adjuvant, triggered both Th1 and Th2 immune responses that protected mice against MERS-CoV challenge [109].

3.2. Preclinical vaccines based on non-S structural proteins of MERS-CoV

Among the four structural proteins of MERS-CoV, the S protein is the most important with respect to developing MERS vaccines. In addition to the S protein, the N protein may serve as an alternative vaccine target since it is highly conserved among different virus strains, and vaccines based on the N protein show immunogenicity in immunized mice. For example, MVA or MV vector-based recombinant vaccines expressing the MERS-CoV N protein (MVA-MERS-N; MVvac2-MERS-N) induce MERS-CoV N-specific T cell (including CD8+ T cell) responses in mice [78,110]. To date, it appears that no other MERS-CoV structural proteins, including E and M, have been used as targets to develop MERS vaccines. It may be possible to combine the E and M proteins with the S protein to form VLP-based MERS vaccines [107].

3.3. Preclinical vaccines based on inactivated virus

The potential of inactivated MERS-CoV virus as a candidate vaccine has been studied [111]. When adjuvanted with aluminum and CpG, inactivated MERS-CoV induced S-specific IgG antibodies with neutralizing activity (similar to those induced by S protein containing the extracellular domain) as well as E-, M-, and N-specific antibodies, which protected Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice from MERS-CoV challenge [111,112]. Nevertheless, hDPP4-Tg mice immunized with inactivated MERS-CoV develop lung immunopathology after challenge with live MERS-CoV, despite elicitation of neutralizing antibodies and reduced viral titers [112].

3.4. Preclinical vaccines based on live-attenuated virus lacking structural, non-structural, or accessory proteins

MERS-CoV ORF 3–5 accessory proteins, the E structural protein, and the nsp16 non-structural protein are associated with virulence or pathogenesis. However, a recombinant MERS-CoV lacking ORF 3–5 reduced viral titers in cell culture [63]. Also, an engineered mutant MERS-CoV lacking the E gene lost virulence at early passages, although it could be rescued and propagated in cells expressing the E protein in trans [55]. Furthermore, a key mutation (D130A) in nsp16 resulted in significant attenuation of MERS-CoV in primary human airway cell cultures and in vivo [61]. These studies provide a rationalized platform for the rapid design of live-attenuated MERS-CoV vaccines with reduced virulence or pathogenesis.

4. Conclusion

The continuing threat of MERS-CoV infection in humans highlights the need to develop safe and effective vaccines. In this review, we described the structure of MERS-CoV and the function of its major proteins, and summarized current MERS candidate vaccines that are under preclinical development, focusing on their immunogenicity and protective efficacy in available animal models. These vaccines are based on the viral S structural protein, the non-S structural proteins, inactivated virus, and live-attenuated virus. Since the S protein is the major target for vaccines against MERS-CoV, vaccines based on the S protein are further classified as DNA, viral vectors, proteins, VLPs, BLPs, and nanoparticles. Overall, this review will provide guidance in the design and development of safe and efficacious vaccines against MERS-CoV. The approaches described in this review could also turn out to be useful in the design and development of safe and efficacious vaccines against other coronaviruses with pandemic potential.

5. Expert opinion

MERS-CoV, an emerging human CoV, is a severe threat to global public health, making it necessary to take continuous and efficient action to control viral infection. Vaccination is one of the most effective strategies to fight against MERS-CoV infection. A variety of MERS vaccines have been developed since the emergence of MERS-CoV in 2012 [1,113]; however, the immunogenicity, tolerability and/or safety of only a few of these vaccines have been evaluated in clinical trials. For example, a DNA vaccine expressing MERS-CoV full-length S protein (GLS-5300) has been tested in a phase I clinical trial; the vaccine induced S1-specific antibodies, T cell responses, and neutralizing antibodies [114]. However, the vaccine can cause injection-site reactions, infections, and systemic symptoms such as headache, malaise, or fatigue [114]. Other MERS vaccines that have been examined in phase I clinical trials include ChAdOx1 (MERS002) [115] and MVA-MERS-S [116], all of which are based on viral vectors expressing the S protein of MERS-CoV.

Almost all other vaccines against MERS-CoV are still under preclinical investigation [113] and the majority of the reported preclinical MERS vaccines are based on the viral structural S protein, including its RBD fragment. Studies of SARS-CoV show that unlike S protein RBD-based vaccines, which elicit neutralizing antibodies and protect mice from lethal SARS-CoV infection [117,118], some SARS-CoV vaccines targeting the full-length S protein may induce antibody-dependent enhancement, in which the antibodies failed to neutralize, but rather enhance, SARS-CoV infection [119,120]. Other reports have linked S-based SARS vaccines with increased inflammatory and immunopathological effects, leading to severe tissue damage [121]. Therefore, the design of novel and safe MERS-CoV vaccines, based on S protein, and particularly its RBD, will require innovative approaches such as the removal or masking of non-neutralizing epitopes and improvements in overall neutralizing ability. In addition, other regions of the S protein, such as S2 or S protein lacking the RBD, may be alternative targets for the design of MERS vaccines. In addition, hDPP4-Tg mice immunized with inactivated MERS-CoV vaccines develop significant lung pathology after virus challenge, although neutralizing antibodies and reduced viral titers are detected in these mice [112]. These studies point out the safety concerns related to the vaccines based on inactivated viruses.

Among all MERS vaccines, viral-vectored vaccines and subunit vaccines are the most extensively developed. In addition to inducing MERS-CoV-specific antibody responses and/or neutralizing antibodies, viral-vectored MERS vaccines, including those based on the MVA and MV, induce neutralizing antibodies and/or T cell responses targeting the viral vectors themselves [67,78,87]. In some cases, such antiviral vector immunity can be beneficial to individuals due to the dual usage of these vaccines as protection against diseases other than MERS [67]. Nevertheless, in the case of using human Ad (such as Ad5), there is a risk of potential side effects, and the presence of pre-existing immunity may affect the generation of subsequent vaccine-specific immune responses. As an alternative approach, chimpanzee Ad vectors can be used to eliminate potential unfavorable immune responses induced by human Ad-vectored MERS vaccines [84].

It should be noted that some protein-based MERS subunit vaccines have limitations due to their low immunogenicity and/or poor efficacy; as such they provide incomplete protection against high-dose MERS-CoV challenge or infection by divergent MERS-CoV strains. Thus, increasing the immunogenicity and/or protective efficacy of these preclinically developed MERS vaccines is warranted. Novel strategies are needed to design MERS subunit vaccines with enhanced efficiency. For example, modification of viral antigens, such as the S protein or its subunit domains, can be used to construct trimeric vaccines with increased stability, or structurally designed subunit vaccines that provide advanced protection [49,50,68]. Other strategies, such as producing multimeric or chimeric antigens, or combining MERS proteins with other immune enhancers, can be considered to develop highly potent MERS subunit vaccines.

Currently, a number of animal models have been developed for the evaluation of efficacy of MERS-CoV candidate vaccines. These include Ad5-hDPP4-transduced mice, hDPP4-KI mice, hDPP4-Tg mice, camels, alpacas, and NHPs [66,103,122–127]. A successful candidate vaccine will need to be evaluated in a lethal animal model, such as hDPP4-Tg mice infected with wildtype MERS-CoV, or hDPP4-KI mice infected with a mouse-adapted MERS-CoV, in which key parameters such as animal survival and immunopathology can be extensively investigated. In addition, before moving to human clinical trials, the vaccines should also be detected for protective efficacy and the related potential pathology in NHPs, an animal model most closely related to humans and capable of emulating the symptoms or immunopathology in humans. Ideally, a successful MERS candidate vaccine is expected to induce strong immune responses with high-titer neutralizing antibodies that completely protect immunized animals from infection of high-dose and divergent MERS-CoV strains, but without inducing lung damage, eosinophilic infiltration, inflammatory cell infiltration, or other lung pathologies.

In addition to MERS-CoV, other MERS-like CoVs have been identified. Similar to MERS-CoV, these bat-originated CoVs also use DPP4 as the receptor to enter hDPP4-expressing cells [128,129], thereby causing MERS-like diseases in humans. Therefore, it is expected that future MERS vaccines will have the ability to induce broad-spectrum immune responses, neutralizing antibodies, and/or protective efficacy against multiple strains of MERS-CoV and MERS-like CoVs with pandemic potential. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 is currently infecting people and the number of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection is increasing globally [6]. Different from MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 has more rapid human-to-human transmission, resulting in growing human infections in Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific regions [6]. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that SARS-CoV-2 potentially recognizes ACE2 in several animal species, including pigs, ferrets, cats, and NHPs [130]. Animal infection studies indicate that ferrets, cats, and NHPs, but not dogs, pigs, chickens, or ducks, are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 [131]. Particularly, ferret and NHP models could be developed to evaluate the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines [131–133]. Although SARS-CoV-2 does not recognize mouse ACE2, transgenic mice expressing the hACE2 receptor (hACE2-Tg) are susceptible [134]. Recently, mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 strains that infect wild-type mice have been established, which provide a convenient and economic approach for evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 [135]. As expected, researchers throughout the world are working around the clock to develop COVID-19 vaccines, some of which, including mRNA-based (mRNA-1273), DNA-based (INO-4800), viral-vectored (Ad5-nCoV, LV-SMENP-DC, and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19), and inactivated SARS-CoV-2 (CoronaVac) vaccines, are being tested in clinical trials [136]. The successful experience for rapid clinical test of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines will provide guidance for moving MERS-CoV vaccines from preclinical studies to clinical trials.

To summarize, although a variety of MERS vaccines have been developed, most are still at the preclinical stage and most have been tested only in small animal models such as mice. These vaccines need to show improved immunogenicity and efficacy with easy preparation and production, reduced cost, and manufacturing capability, to be evaluated in vivo with respect to safety, tolerability, and toxicity, and to be investigated for immunogenicity and protection in large animal models prior to human trials. Over the next five years, we anticipate the development of safer and more effective MERS vaccines with low-cost, easy-preparation, and high manufacturing capability for clinical use. Of these, vaccines targeting the viral structural S protein are likely to show the greatest potential for further development. Although herd immunity may be considered as an alternative approach for the prevention of MERS-CoV infection, this strategy may not be applicable to MERS in view of its high mortality (~34.4%), which is about ten times that of COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2. Because of the potential for cross-species transmission of MERS-like CoVs, more MERS vaccines that provide effective cross-protection against multiple MERS-CoV strains and MERS-like CoVs will be needed to prevent future pandemics. Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 and the pandemic potential of SARS-like or MERS-like CoVs, pharmaceutical companies and government funding agencies are backing financially programs aimed at accelerating the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and/or universal or pan-CoV vaccines. For example, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has invested funds to support the development of COVID-19 vaccines in collaboration with global health authorities and vaccine developers, via various sources, such as CEPI internal sources through the COVID-19 Call for Proposal process (CFP2R), clinical trial databases (ClinicalTrials.gov), and funder databases (BARDA) [137]. It is hoped that they will invest more funds to implement human trials of preclinical MERS vaccines that show high immunogenicity, strong efficacy, low-cost, and no toxicity. Nevertheless, owing to limited funds, strict regulation by the FDA and other regulatory agencies, and the high cost of testing immunogenicity, tolerability, and safety in humans, there appears to be a long way to go before preclinical MERS vaccines can progress to clinical trials.

Article highlights.

MERS-CoV, an emerging human coronavirus (CoV), belongs to the same β-genus as SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. But MERS-CoV is distinctive from SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2: it is a member in lineage C, whereas SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are associated with lineage B, of β-CoV genus. MERS-CoV causes severe infections in humans, with a global fatality rate of about 34.4%; thus, there is an urgent need to design and develop novel vaccines that protect against MERS-CoV infection.

MERS-CoV is a zoonotic CoV originating from bats, utilizing dromedary camels as its most important intermediate host. Camel-to-human and human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV has been identified, although transmission between humans is limited.

The genome of MERS-CoV encodes four major structural proteins (spike (S), nucleocapsid (S), membrane (M), and envelope (E)), 16 nsps, and five accessory proteins. The structure and/or function of some of these proteins have been determined, thereby providing a basis for the design of effective MERS vaccines.

MERS-CoV recognizes human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) as its cellular receptor to bind to target cells via the receptor-binding domain (RBD) within the S protein, thereby mediating virus entry and membrane fusion through the S2 region of the S protein. In addition to MERS-CoV, several MERS-like CoVs may also utilize hDPP4 as the receptor for cell entry.

Most currently developed MERS vaccines are under preclinical development; these vaccines are based on the MERS-CoV S protein, non-S structural proteins (such as N protein), inactivated virus, or live-attenuated virus.

MERS-CoV S protein is an important target for the development of MERS vaccines; the majority of the currently designed MERS vaccines are based on this protein. These vaccines can be further classified as DNA, viral vector, protein (subunit), VLP, BLP, and nanoparticle vaccines, most of which have been evaluated for immunogenicity and/or efficacy in mice. Some have been tested in camels and/or NHPs.

MERS vaccines of each type have both advantages and disadvantages. Novel strategies are needed to design safe and effective vaccines to eliminate potential harmful effects, and preserve and/or improve the immunogenicity and efficacy of current MERS vaccines.

At present, no MERS vaccines have been approved for use in humans, and only a very limited number (including those based on DNA and viral vectors) have been tested for immunogenicity and/or safety in phase I clinical trials. Lacking of sufficient funds prevents the progression of vaccines from preclinical studies to clinical trials. Therefore, more funding from all sources is anticipated to speed up progress to testing in humans.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants [R01AI137472, R01AI157975, and R01AI139092].

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Footnotes

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Du L, Tai W, Zhou Y, et al. Vaccines for the prevention against the threat of MERS-CoV. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(9):1123–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan J, Lau S, Woo P. The emerging novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: the “knowns” and “unknowns”. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112(7):372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du L, He Y, Zhou Y, et al. The spike protein of SARS-CoV–a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(3):226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382 (8):727–733.•• A report on the emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update. [cited August 24, 2020]. Available from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200824-weekly-epi-update.pdf?sfvrsn=806986d1_4.

- 7.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, et al. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814–1820.•• A report on the isolation of MERS-CoV from human.

- 8.WHO. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). [cited 2019] Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/.

- 9.Park JE, Jung S, Kim A, et al. MERS transmission and risk factors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015;6(4):269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li F, Du L. MERS coronavirus: an emerging zoonotic virus. Viruses. 2019;11(7):E663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495(7440):251–254.•• A report about identification of MERS-CoV receptor dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4).

- 13.Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, et al. Structure basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581(7807):221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426 (6965):450–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, Qi J, Yuan Y, et al. Bat origins of MERS-CoV supported by bat coronavirus HKU4 usage of human receptor CD26. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(3):328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Du L, Liu C, et al. Receptor usage and cell entry of bat coronavirus HKU4 provide insight into bat-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(34):12516–12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Liu C, Du L, et al. Two mutations were critical for bat-to-human transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2015;89(17):9119–9123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo PCY, Lau SKP, Chen Y, et al. Rapid detection of MERS coronavirus-like viruses in bats: pote1ntial for tracking MERS coronavirus transmission and animal origin. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olival KJ, Hosseini PR, Zambrana-Torrelio, et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature. 2017;546(7660):646–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(2):140–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA, et al. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2014;370 (26):2499–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayali G, Peiris M. A more detailed picture of the epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):495–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller MA, Corman VM, Jores J, et al. MERS coronavirus neutralizing antibodies in camels, Eastern Africa, 1983–1997. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(12):2093–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller MA, Meyer B, Corman VM, et al. Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide, cross-sectional, serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adney DR, van Doremalen N, Brown VR, et al. Replication and shedding of MERS-CoV in upper respiratory tract of inoculated dromedary camels. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(12):1999–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalafalla AI, Lu X, Al-Mubarak AI, et al. MERS-CoV in upper respiratory tract and lungs of dromedary camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(7):1153–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Killerby ME, Biggs HM, Midgley CM, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(2):191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Memish ZA, Cotten M, Meyer B, et al. Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(6):1012–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikkema RS, Farag E, Himatt S, et al. Risk factors for primary Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in camel workers in Qatar during 2013–2014: a case-control study. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(11):1702–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alshukairi AN, Zheng J, Zhao J, et al. High prevalence of MERS-CoV infection in camel workers in Saudi Arabia. mBio. 2018;9(5):e01985–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drosten C, Meyer B, Muller MA, et al. Transmission of MERS-coronavirus in household contacts. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KH, Tandi TE, Choi JW, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in South Korea, 2015: epidemiology, characteristics and public health implications. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(2):207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio. 2012;3(6):e00473–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du L, Yang Y, Zhou Y, et al. MERS-CoV spike protein: a key target for antivirals. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21(2):131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang N, Jiang S, Du L. Current advancements and potential strategies in the development of MERS-CoV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(6):761–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu G, Hu Y, Wang Q, et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature. 2013;500(7461):227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Rajashankar KR, Yang Y, et al. Crystal structure of the receptor-binding domain from newly emerged Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2013;87(19):10777–10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W, Hulswit RJG, Widjaja I, et al. Identification of sialic acid-binding function for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(40): E8508–E8517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widagdo W, Okba NMA, Li W, et al. Species-specific colocalization of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus attachment and entry receptors.. J Virol. 2019;93(16):e00107–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park YJ, Walls AC, Wang Z, et al. Structures of MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein in complex with sialoside attachment receptors. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019;26(12):1151–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu L, Liu Q, Zhu Y, et al. Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3067.•• A report about identification of a MERS-CoV S-based fusion inhibitor.

- 42.Boonacker E, Van Noorden CJ. The multifunctional or moonlighting protein CD26/DPPIV. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82(2):53–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang N, Shi X, Jiang L, et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013;23(8):986–993.•• A report about the structure of MERS-CoV RBD complexed with viral receptor human DPP4.

- 44.Bosch BJ, Raj VS, Haagmans BL. Spiking the MERS-coronavirus receptor. Cell Res. 2013;23(9):1069–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirato K, Kawase M, Matsuyama S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection mediated by the transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J Virol. 2013;87(23):12552–12561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kleine-Weber H, Elzayat MT, Hoffmann M, et al. Functional analysis of potential cleavage sites in the MERS-coronavirus spike protein. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qian Z, Dominguez SR, Holmes KV. Role of the spike glycoprotein of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in virus entry and syncytia formation. PloS One. 2013;8(10):e76469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Earnest JT, Hantak MP, Li K, et al. The tetraspanin CD9 facilitates MERS-coronavirus entry by scaffolding host cell receptors and proteases. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(7):e1006546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pallesen J, Wang N, Corbett KS, et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(35):E7348–E7357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan Y, Cao D, Zhang Y, et al. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang N, Rosen O, Wang L, et al. Structural definition of a neutralization-sensitive epitope on the MERS-CoV S1-NTD. Cell Rep. 2019;28(13):3395–3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goddard TD, Huang CC, Frrrin TE. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. J Struct Biol. 2007;157(1):281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li YH, Hu CY, Wu NP, et al. Molecular characteristics, functions, and related pathogenicity of MERS-CoV proteins. Engineering. 2019;5(5):940–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Surya W, Li Y, Verdia-Baguena C, et al. MERS coronavirus envelope protein has a single transmembrane domain that forms pentameric ion channels. Virus Res. 2015;201:61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Almazan F, DeDiego ML, Sola I, et al. Engineering a replication-competent, propagation-defective Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as a vaccine candidate. mBio. 2013;4(5): e00650–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papageorgiou N, Lichiere J, Baklouti A, et al. Structural characterization of the N-terminal part of the MERS-CoV nucleocapsid by X-ray diffraction and small-angle X-ray scattering. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2016;72(Pt 2):192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang YS, Chang CK, Hou MH. Crystallographic analysis of the N-terminal domain of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2015;71(Pt 8):977–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho CC, Lin MH, Chuang CY, et al. Macro domain from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is an efficient ADP-ribose binding module: Crystal structure and biochemical studies. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(10):4894–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hao W, Wojdyla JA, Zhao R, et al. Crystal structure of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13 (6):e1006474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang L, Li L, Yan L, et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of endoribonuclease Nsp15 encoded by Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2018;92(22):e00893–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menachery VD, Gralinski LE, Mitchell HD, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 16 is necessary for interferon resistance and viral pathogenesis. mSphere. 2017;2 (6):e00346–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee JY, Bae S, Myoung J. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus-encoded ORF8b strongly antagonizes IFN-beta promoter activation: its implication for vaccine design. J Microbiol. 2019;57(9):803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scobey T, Yount BL, Sims AC, et al. Reverse genetics with a full-length infectious cDNA of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110 (40):16157–16162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang C, Zheng X, Gai W, et al. Novel chimeric virus-like particles vaccine displaying MERS-CoV receptor-binding domain induce specific humoral and cellular immune response in mice. Antiviral Res. 2017;140:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li E, Chi H, Huang P, et al. A novel bacterium-like particle vaccine displaying the MERS-CoV receptor-binding domain induces specific mucosal and systemic immune responses in mice. Viruses. 2019;11 (9):E799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muthumani K, Falzarano D, Reuschel EL, et al. A synthetic consensus anti-spike protein DNA vaccine induces protective immunity against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in non-human primates. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(301):301ra132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haagmans BL, van den Brand JM, Raj VS, et al. An orthopoxvirus-based vaccine reduces virus excretion after MERS-CoV infection in dromedary camels. Science. 2016;351 (6268):77–81.•• A reprot describing a viral-vectored MERS-CoV vaccine.

- 68.Du L, Tai W, Yang Y, et al. Introduction of neutralizing immunogenicity index to the rational design of MERS coronavirus subunit vaccines. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13473.•• A report describing an RBD protein-based MERS-CoV vaccine with improved efficacy.

- 69.Coleman CM, Venkataraman T, Liu YV, et al. MERS-CoV spike nanoparticles protect mice from MERS-CoV infection. Vaccine. 2017;35 (12):1586–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chi H, Zheng X, Wang X, et al. DNA vaccine encoding Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus S1 protein induces protective immune responses in mice. Vaccine. 2017;35(16):2069–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al-Amri SS, Abbas AT, Siddiq LA, et al. Immunogenicity of candidate MERS-CoV DNA vaccines based on the spike protein. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang L, Shi W, Joyce MG, et al. Evaluation of candidate vaccine approaches for MERS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Volz A, Kupke A, Song F, et al. Protective efficacy of recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara delivering Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. J Virol. 2015;89 (16):8651–8656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guo X, Deng Y, Chen H, et al. Systemic and mucosal immunity in mice elicited by a single immunization with human adenovirus type 5 or 41 vector-based vaccines carrying the spike protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Immunology. 2015;145(4):476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Song F, Fux R, Provacia LB, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein delivered by modified vaccinia virus Ankara efficiently induces virus-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87(21):11950–11954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ababneh M, Alrwashdeh M, Khalifeh M. Recombinant adenoviral vaccine encoding the spike 1 subunit of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus elicits strong humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. Vet World. 2019;12(10):1554–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu R, Wang J, Shao Y, et al. A recombinant VSV-vectored MERS-CoV vaccine induces neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in rhesus monkeys after single dose immunization. Antiviral Res. 2018;150:30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bodmer BS, Fiedler AH, Hanauer JRH, et al. Live-attenuated bivalent measles virus-derived vaccines targeting Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus induce robust and multifunctional T cell responses against both viruses in an appropriate mouse model. Virology. 2018;521:99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Langenmayer MC, Lulf-Averhoff AT, Adam-Neumair S, et al. Distribution and absence of generalized lesions in mice following single dose intramuscular inoculation of the vaccine candidate MVA-MERS-S. Biologicals. 2018;54:58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim E, Okada K, Kenniston T, et al. Immunogenicity of an adenoviral-based Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2014;32(45):5975–5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hashem AM, Algaissi A, Agrawal AS, et al. A highly immunogenic, protective, and safe adenovirus-based vaccine expressing Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus S1-CD40L fusion protein in a transgenic human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 mouse model. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(10):1558–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim MH, Kim HJ, Chang J. Superior immune responses induced by intranasal immunization with recombinant adenovirus-based vaccine expressing full-length spike protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alharbi NK, Qasim I, Almasoud A, et al. Humoral immunogenicity and efficacy of a single dose of ChAdOx1 MERS vaccine candidate in dromedary camels. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jia W, Channappanavar R, Zhang C, et al. Single intranasal immunization with chimpanzee adenovirus-based vaccine induces sustained and protective immunity against MERS-CoV infection. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):760–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alharbi NK, Padron-Regalado E, Thompson CP, et al. ChAdOx1 and MVA based vaccine candidates against MERS-CoV elicit neutralizing antibodies and cellular immune responses in mice. Vaccine. 2017;35(30):3780–3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ozharovskaia TA, Zubkova OV, Dolzhikova IV, et al. Immunogenicity of different forms of Middle East respiratory syndrome S glycoprotein. Acta Naturae. 2019;11(1):38–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malczyk AH, Kupke A, Prufer S, et al. A highly immunogenic and protective Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine based on a recombinant measles virus vaccine platform. J Virol. 2015;89(22):11654–11667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Du L, Zhao G, Kou Z, et al. Identification of a receptor-binding domain in the S protein of the novel human coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an essential target for vaccine development. J Virol. 2013;87(17):9939–9942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ma C, Li Y, Wang L, et al. Intranasal vaccination with recombinant receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein induces much stronger local mucosal immune responses than subcutaneous immunization: Implication for designing novel mucosal MERS vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32(18):2100–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ma C, Wang L, Tao X, et al. Searching for an ideal vaccine candidate among different MERS coronavirus receptor-binding fragments–the importance of immunofocusing in subunit vaccine design. Vaccine. 2014;32(46):6170–6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lan J, Yao Y, Deng Y, et al. Recombinant receptor binding domain protein induces partial protective immunity in rhesus macaques against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus challenge. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(10):1438–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adney DR, Wang L, van Doremalen N, et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein vaccine in dromedary camels and alpacas. Viruses. 2019;11(3):E212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou Y, Yang Y, Huang J, et al. Advances in MERS-CoV vaccines and therapeutics based on the receptor-binding domain. Viruses. 2019;11(1):E60.• A report summarizing the MERS-CoV RBD-based vaccines and therapeutics.

- 94.Mou H, Raj VS, van Kuppeveld FJ, et al. The receptor binding domain of the new Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus maps to a 231-residue region in the spike protein that efficiently elicits neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87(16):9379–9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lan J, Deng Y, Chen H, et al. Tailoring subunit vaccine immunity with adjuvant combinations and delivery routes using the Middle East respiratory coronavirus (MERS-CoV) receptor-binding domain as an antigen. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tai W, Wang Y, Fett CA, et al. Recombinant receptor-binding domains of multiple Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses (MERS-CoVs) induce cross-neutralizing antibodies against divergent human and camel MERS-CoVs and antibody escape mutants. J Virol. 2016;91(1):e01651–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tai W, Zhao G, Sun S, et al. A recombinant receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV in trimeric form protects human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) transgenic mice from MERS-CoV infection. Virology. 2016;499:375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nyon MP, Du L, Tseng CK, et al. Engineering a stable CHO cell line for the expression of a MERS-coronavirus vaccine antigen. Vaccine. 2018;36(14):1853–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Du L, Kou Z, Ma C, et al. A truncated receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein potently inhibits MERS-CoV infection and induces strong neutralizing antibody responses: implication for developing therapeutics and vaccines. PloS One. 2013;8(12):e81587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang N, Channappanavar R, Ma C, et al. Identification of an ideal adjuvant for receptor-binding domain-based subunit vaccines against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13(2):180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tang J, Zhang N, Tao X, et al. Optimization of antigen dose for a receptor-binding domain-based subunit vaccine against MERS coronavirus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(5):1244–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang Y, Tai W, Yang J, et al. Receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV with optimal immunogen dosage and immunization interval protects human transgenic mice from MERS-CoV infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(7):1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tao X, Garron T, Agrawal AS, et al. Characterization and demonstration of the value of a lethal mouse model of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection and disease. J Virol. 2015;90(1):57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jiaming L, Yanfeng Y, Yao D, et al. The recombinant N-terminal domain of spike proteins is a potential vaccine against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection. Vaccine. 2017;35(1):10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lan J, Deng Y, Song J, et al. Significant spike-specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies in mice induced by a novel chimeric virus-like particle vaccine candidate for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Virol Sin. 2018;33(5):453–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang C, Zheng X, Gai W, et al. MERS-CoV virus-like particles produced in insect cells induce specific humoral and cellular immunity in rhesus macaques. Oncotarget. 2017;8(8):12686–12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Coleman CM, Liu YV, Mu H, et al. Purified coronavirus spike protein nanoparticles induce coronavirus neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 2014;32(26):3169–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kato T, Takami Y, Kumar Deo V, et al. Preparation of virus-like particle mimetic nanovesicles displaying the S protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus using insect cells. J Biotechnol. 2019;306:177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jung SY, Kang KW, Lee EY, et al. Heterologous prime-boost vaccination with adenoviral vector and protein nanoparticles induces both Th1 and Th2 responses against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Vaccine. 2018;36(24):3468–3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Veit S, Jany S, Fux R, et al. CD8+ T cells responding to the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein delivered by Vaccinia virus MVA in mice. Viruses. 2018;10(12):E718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Deng Y, Lan J, Bao L, et al. Enhanced protection in mice induced by immunization with inactivated whole viruses compare to spike protein of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Agrawal AS, Tao X, Algaissi A, et al. Immunization with inactivated Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine leads to lung immunopathology on challenge with live virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(9):2351–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhou Y, Jiang S, Du L. Prospects for a MERS-CoV spike vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(8):677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Modjarrad K, Roberts CC, Mills KT, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an anti-Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus DNA vaccine: a phase 1, open-label, single-arm, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(9):1013–1022.• A report about the phase I clinical trial of a DNA-based MERS-CoV vaccine.

- 115.A clinical trial to determine the safety and immunogenicity of healthy candidate MERS-CoV vaccine (MERS002). [cited Dec 26, 2019]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04170829.• A report describing the status of phase I clinical trial of a MERS-CoV vaccine based on viral vector (ChAdOx1).

- 116.Safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of vaccine candidate MVA-MERS-S. [cited Dec 26, 2019]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03615911.• A report describing the status of phase I clinical trial of a MERS-CoV vaccine based on viral vector (MVA).

- 117.Chen WH, Tao X, Agrawal A, et al. Yeast-expressed SARS-CoV recombinant receptor-binding domain (RBD219-N1) formulated with alum induces protective immunity and reduces immune enhancement. bioRxiv. 2020;098079 DOI: 10.1101/2020.05.15.098079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chen WH, Du L, Chag SM, et al. Yeast-expressed recombinant protein of the receptor-binding domain in SARS-CoV spike protein with deglycosylated forms as a SARS vaccine candidate. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(3):648–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]