Abstract

Background & Aims:

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy fails to provide adequate symptom control in up to 50% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. While a proportion do not require ongoing PPI therapy, a diagnostic approach to identify candidates appropriate for PPI cessation is not available. This study aimed to examine the clinical utility of prolonged wireless reflux monitoring to predict ability to discontinue PPI.

Methods:

This double-blinded clinical trial performed over three years at two centers enrolled adults with troublesome esophageal symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, and/or chest pain and inadequate PPI response. Participants underwent prolonged wireless reflux monitoring (off PPI for ≥7 days) and a three-week PPI cessation intervention. Primary outcome was tolerance of PPI cessation (discontinued or resumed PPI). Symptom burden was quantified using the Reflux Symptom Questionnaire electronic Diary (RESQ-eD).

Results:

Of 128 enrolled, 100 participants met inclusion criteria (mean age 48.6 years; 41 male). Thirty-four (34%) participants discontinued PPI. The strongest predictor of PPI discontinuation was number of days with acid exposure time (AET)>4.0% (OR 1.82;p<0.001). Participants with 0 days of AET>4.0% had a 10 times increased odds of discontinuing PPI than participants with 4 days of AET>4.0%. Reduction in symptom burden was greater among the discontinued versus resumed PPI group (RESQ-eD: −43.7% vs −5.3%;p=0.04).

Conclusion:

Among patients with typical reflux symptoms, inadequate PPI response, and absence of severe esophagitis, acid exposure on reflux monitoring predicted ability to discontinue PPI without symptom escalation. Upfront reflux monitoring off acid suppression can limit unnecessary PPI use and guide personalized management.

Trial Registry:

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Bravo

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects up to 30% of the adult US population and is among the most frequent gastrointestinal diagnoses in both primary care and sub-specialty settings.1–3 Clinically, GERD is suspected based on patient report of troublesome esophageal symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, and non-cardiac chest pain.2 First-line management relies on empiric trials of acid suppression, namely proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, and consequently, PPIs are among the most widely prescribed class of medications worldwide.2, 3 However, up to 50% of patients do not derive adequate symptom relief with PPI therapy, incurring substantial health care burden, with annual drug costs for PPIs alone exceeding $12 billion, and annual US health care expenditures of GERD accounting for up to $20 billion.3–6 Since 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign has sought to minimize unneeded PPI use for GERD symptoms.7 Rising concerns regarding risks of long-term PPI use have further motivated patients and the medical community to reduce PPI utilization.8, 9 Unfortunately, validated approaches to identify appropriate candidates for PPI cessation are not available.

Prolonged wireless reflux monitoring is widely utilized to quantify esophageal acid exposure and assess associations between reflux episodes and patient reported symptoms.10 A large proportion of symptomatic patients with inadequate PPI response have normal levels of esophageal acid exposure on reflux monitoring.3, 4, 11, 12 However, the clinical utility of reflux monitoring to guide management, especially whether patients with normal reflux monitoring will tolerate cessation of PPI therapy, remains unknown. We hypothesize that prolonged reflux monitoring reliably identifies appropriate candidates for PPI cessation. In this prospective clinical trial, we aimed to examine the clinical utility of prolonged wireless reflux monitoring to predict ability to discontinue PPI therapy among a population of patients with gastro-esophageal reflux symptoms and inadequate PPI response.

METHODS

Study Design

This double-blind single-arm clinical trial was conducted over three years (May 2017 to May 2020) at two tertiary-care centers (Lead site: Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Second site: Washington University, St. Louis, MO). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at participating sites and registered with clinicaltrials.gov NCT03202537. This overarching trial (NIH R01 DK092217–04) enrolled adults with gastro-esophageal reflux symptoms and inadequate response to PPI therapy in order to assess the clinical utility of esophageal physiologic tools. The analysis presented in this paper focused on performance of prolonged reflux monitoring to predict ability to stop PPI therapy for three weeks.

Study Population

Adult patients with troublesome symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and non-cardiac chest pain, defined as at least two episodes per week according to the Montreal definition, that remained symptomatic despite a compliant trial of single-dose PPI therapy for at least 8 weeks were eligible for enrollment. Patients may have also experienced concurrent extra-esophageal symptoms such as cough, globus, sore throat, or dysphonia, however patients with isolated extra-esophageal symptoms were not included. Exclusionary criteria included active severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles C or D), long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (≥3cm in length), prior foregut surgery, signs or symptoms of heart disease, pregnancy, manometric evidence of a major motility disorder according to Chicago Classification version 3.013), or >15 eosinophils per high power field on esophageal biopsies obtained for endoscopic signs of eosinophilic esophagitis. Patients with insufficient pH monitoring time captured (at least 14 hours/day for ≥ 3 days) were also excluded. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study Protocol & Intervention

The study intervention was PPI cessation for three weeks. After remaining off PPI therapy for one week participants underwent 96-hour wireless reflux monitoring. Subsequently, participants were instructed to refrain from resuming PPI therapy for an additional two weeks unless esophageal symptoms escalated to the extent that maximal over the counter antacid utilization did not provide adequate symptom control. Participants and study investigators were blind to results of reflux testing during the intervention.

Wireless pH Monitoring

During a sedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, the wireless pH delivery catheter system (Bravo; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) was introduced transorally and the pH capsule was positioned 6 cm proximal to the endoscopically identified squamocolumnar junction, corresponding to 5cm above the proximal border of the lower esophageal sphincter. Once the system was in appropriate position, the external portable vacuum pump was switched on to apply suction to the well of the capsule and suck in adjacent esophageal mucosa. After 30 seconds, the plastic safety guard was removed and the activation button was depressed. Participants were instructed to remain within 3 feet of the pager-sized receiver at all times, continue usual activities, remain off PPI, and log symptoms/meals in a written and electronic diary. Participants returned the wireless pH study receiver 96 hours later.

Esophageal Physiologic Tests

As a part of the study protocol, participants also underwent high-resolution impedance esophageal manometry and 24-hour multi-channel intraluminal impedance-pH monitoring on PPI, either at the time of enrollment prior to PPI cessation or at a later date following the PPI cessation trial per patient and/or site preference.

Patient Reported Symptoms

At enrollment participants completed the GerdQ instrument, a six-item validated questionnaire evaluating reflux symptoms with a 7-day recall period with scores ranging from 0 to 18, where higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.14, 15 Participants also completed the Reflux Symptom Questionnaire electronic Diary (RESQ-eD) during the daytime and nighttime at four time points during the study: on PPI at time of enrollment and off PPI at week one, two and three. The RESQ-eD is a validated electronic symptom diary for use in patients with symptoms of GERD and inadequate response to PPI developed in line with FDA guidance on patient-reported outcomes which measures symptom intensity ranging from 0 to 5 for 13 symptoms in the morning and before bedtime, with a 7-day recall period, where higher scores indicate higher symptom burden.16 The study coordinator contacted participants weekly for four weeks to monitor symptoms, collect questionnaire scores, and determine whether PPI therapy was resumed.

Data Source & Measurement

Data for all participants were electronically collected in a uniform de-identified dataset through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) hosted at the lead study site with multi-site access for the secondary participating center. Data collected for participants included demographics, endoscopic findings (presence/degree of erosive esophagitis, hiatal hernia size), eosinophil count on esophageal biopsy, questionnaire scores, and PPI use. Reflux monitoring data analyzed by a blinded external investigator using manufacturer software (AccuView Reflux Software; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) included monitoring time, total and daily acid exposure time (AET; percent time esophageal acid exposure is below pH of 4.0), DeMeester score, number of reflux events, longest reflux event, symptoms reported, symptom index (proportion of symptoms associated with a reflux episode; optimal threshold > 50%) and symptom association probability (a statistical calculation expressing the probability that symptom events and reflux episodes are associated; ≥5% considered positive).10 All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was status of PPI use during the study intervention, categorized as discontinued PPI or resumed PPI. Secondary outcomes included change in symptoms during the study intervention measured by absolute and percentage change in RESQ-eD score, and presence of objective GERD on reflux monitoring.

Sample Size

The target sample size for this analysis was 100 participants. Anticipating successful PPI discontinuation in approximately 70% of participants with 0 days positive AET compared to 40% of participants with ≥1 day positive AET, a sample size of 84 would provide a type I error rate of 0.05 and power of 80%.

Data Analysis

All data are summarized as count (percent) or mean (standard deviation) for categorical or continuous variables, respectively. The primary analysis aimed to assess the potential utility of various demographic, clinical, and physiological measures on reflux monitoring to predict outcome of PPI cessation. Univariate logistic regression models were fit with summaries including the odds ratio with its confidence interval and p-value and c-statistic. The c-statistic represents the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) corresponding to the logistic regression model. AET as measured over the course of four days of reflux monitoring was also classified by number of days with acid exposure above 4.0, 5.0, or 6.0% to examine if an optimal combination could identify those likely to discontinue PPI. Two-sample t-tests assuming unequal variances were used to compare means between PPI cessation groups. A secondary analysis assessed the predictor of symptom severity measured by RESQ-eD at baseline and change throughout the study with the outcome of GERD or no GERD using univariate logistic regression models. All figures and analyses were conducted using R v3.6.0 (Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

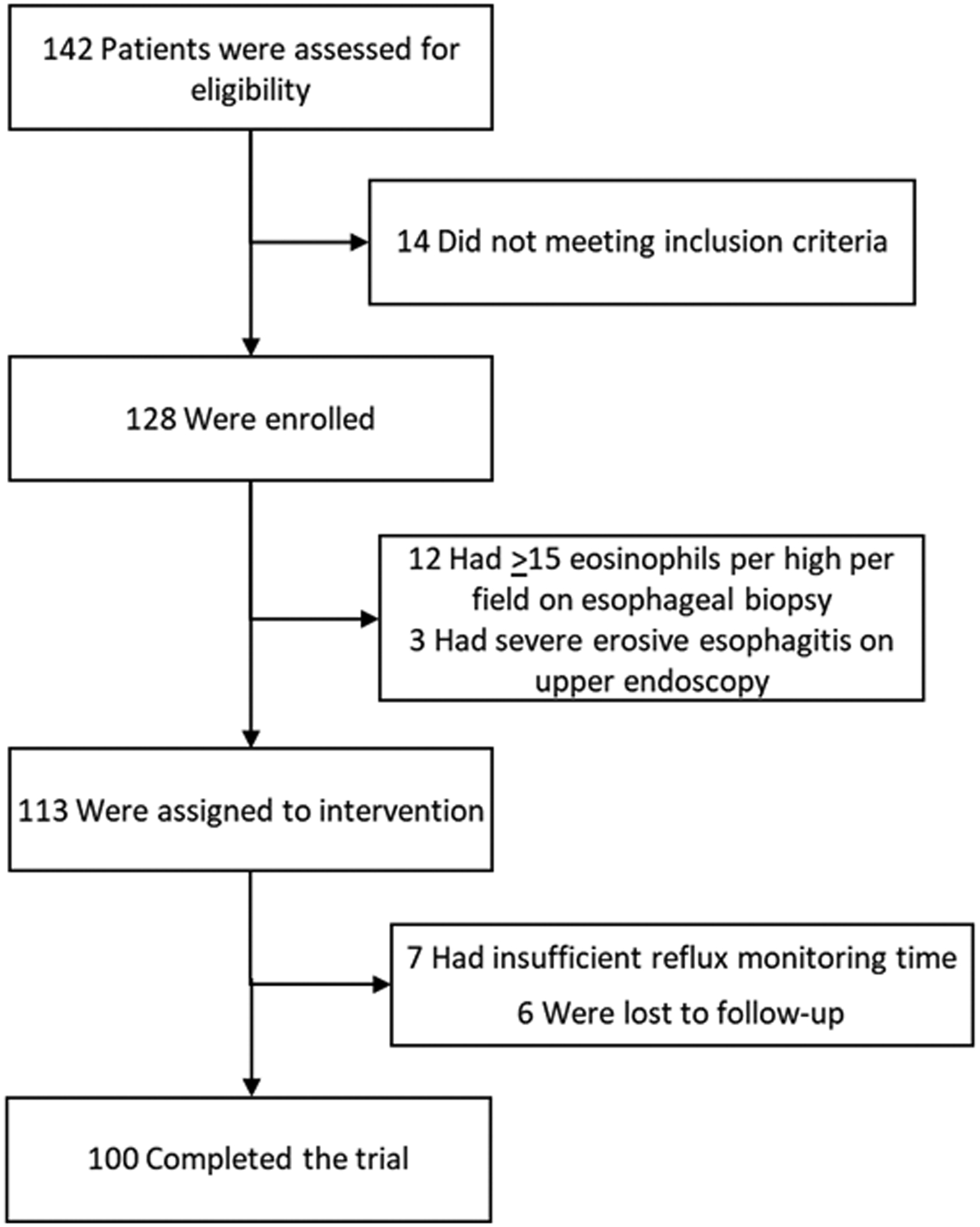

Of 142 patients screened, 128 met eligibility and provided informed consent of which 100 participants met inclusion criteria, completed the study and are included in the analysis (Figure 1). Among the included participants, 41% were male with a mean age of 48.6 years (SD 14.9) and mean body mass index of 27.1 kg/m2 (SD 5.5). Participants reported a mean GerdQ score of 8.6 (SD 4.2) at intake. On upper endoscopy 30 participants had erosive esophagitis (16 Los Angeles A and 14 Los Angeles B esophagitis) and 27 participants had a hiatal hernia. Mean reflux monitoring time was 3.4 days (SD 0.3) with a mean total esophageal AET of 5.8% (SD 3.8) and mean DeMeester score 21.6 (SD 13.6) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment and Inclusion of Patients

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics & Factors Associated with Outcome of PPI Cessation Intervention

| Predictor | All Subjects (n 100) | PPI Discontinued (n 34) | PPI Resumed (n 66) |

OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 48.6 (14.9) | 47.7 (14.3) | 49.0 (15.3) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.68 |

| Male | 41 (41%) | 13 (38.2%) | 28 (42.4%) | 1.19 (0.51, 2.82) | 0.69 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.1 (5.48) | 27.4 (4.7) | 27.0 (5.9) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.79 |

| Hiatal hernia | 27 (27%) | 10 (29.4%) | 17 (25.8%) | 0.83 (0.33, 2.14) | 0.70 |

| Esophagitis | |||||

| Los Angeles A | 16 (16%) | 4 (11.8%) | 12 (18.2%) | Reference | |

| Los Angeles B | 14 (14%) | 5 (14.7%) | 9 (13.6%) | 0.60 (0.12, 2.90) | 0.53 |

| None | 70 (70%) | 25 (73.5%) | 45 (68.2%) | 0.60 (0.15, 1.93) | 0.42 |

| Baseline symptoms | |||||

| Index RESQ-eD Score | 19.1 (11.8) | 12.0 (9.6) | 17.8 (11.7) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 0.02 |

| Index GerdQ Score | 8.6 (4.23) | 7.2 (3.0) | 9.3 (4.6) | 1.19 (1.04, 1.39) | 0.02 |

| Heartburn | 68 (68%) | 22 (64.7%) | 46 (69.7%) | 1.25 (0.51, 3.01) | 0.61 |

| Regurgitation | 38 (38%) | 10 (29.4%) | 28 (42.4%) | 1.77 (0.74, 4.42) | 0.21 |

| Chest pain | 38 (38%) | 16 (47.1%) | 22 (33.3%) | 0.56 (0.24, 1.31) | 0.18 |

| Wireless pH monitoring | |||||

| AET Total, % | 5.8 (3.8) | 4.3 (3.6) | 6.6 (3.6) | 1.21 (1.07, 1.39) | 0.01 |

| DeMeester Score | 21.6 (13.6) | 16.2 (12.6) | 24.3 (13.4) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.10) | 0.01 |

| DeMeester Score > 14.2 | 67 (67%) | 17 (50%) | 50 (76%) | 3.12 (1.31, 7.63) | 0.01 |

| Number Reflux Events | 127 (80.2) | 104.3 (80.6) | 138.2 (78.1) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.05 |

| Longest Reflux Event, min | 32.0 (24.8) | 22.7 (16.8) | 36.9 (26.9) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.06) | 0.01 |

| Lowest Daily AET | 3.0 (2.72) | 2.0 (2.4) | 3.5 (2.8) | 1.28 (1.07, 1.57) | 0.01 |

| Highest Daily AET | 9.82 (6.48) | 7.4 (5.4) | 11.1 (6.6) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.22) | 0.01 |

| Number of Days AET >4.0% | 2.2 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.3) | 1.82 (1.34, 2.56) | <0.01 |

| Number of Days AET >5.0% | 1.9 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.4) | 1.73 (1.27, 2.44) | <0.01 |

| Number of Days AET >6.0% | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.4) | 1.65 (1.20, 2.37) | <0.01 |

| AET > 4 for 1+ Days | 82 (82%) | 22 (65%) | 60 (91%) | 5.45 (1.88, 17.37) | <0.01 |

| AET > 4 for 2+ Days | 66 (66%) | 14 (41%) | 52 (79%) | 5.31 (2.19, 13.44) | <0.01 |

| AET > 4 for 3+ Days | 46 (46%) | 8 (24%) | 38 (58%) | 4.41 (1.80, 11.78) | <0.01 |

| AET > 4 for 4+ Days | 30 (30%) | 5 (15%) | 25 (38%) | 3.54 (1.29, 11.45) | 0.02 |

| Symptom index for heartburn | 19.1 (24.3) | 12.6 (22.9) | 22.5 (24.5) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.06 |

| Symptom index for regurgitation | 11.1 (24.1) | 8.7 (24.8) | 12.4 (23.9) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.47 |

| Symptom index for chest pain | 6.0 (17.9) | 4.3 (17.5) | 6.8 (18.1) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.52 |

| SAP for heartburn | 44.8 (47.4) | 30.2 (44.9) | 52.3 (47.2) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.03 |

| SAP for regurgitation | 20.8 (35.2) | 13.6 (33.2) | 24.5 (40.8) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.18 |

| SAP for chest pain | 14.0 (31.7) | 10.8 (26.7) | 15.7 (34.0) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.47 |

| SAP > 95% for heartburn, regurgitation or chest pain | 46 (46%) | 11 (32%) | 35 (53%) | 2.36 (1.01, 5.77) | 0.052 |

| Change in RESQeD Score from Baseline | |||||

| Absolute change week 1 | 1.11 (8.04) | 2.14 (8.78) | −0.58 (6.43) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.12) | 0.142 |

| Absolute change week 2 | −2.35 (8.97) | −1.41 (9.9) | −3.9 (7.07) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.231 |

| Absolute change week 3 | −4.52 (10.1) | −3.21 (10.8) | −6.69 (8.58) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 0.150 |

| Percent change week 1, % | 15.2 (67.4) | 24.7 (75.7) | −0.45 (48.0) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.106 |

| Percent change week 2, % | −5.71 (73.3) | 4.09 (75.3) | −21.7 (68.3) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.135 |

| Percent change week 3, % | −19.8 (78.8) | −5.31 (86.4) | −43.7 (58.1) | 1.01 (1.002, 1.02) | 0.039 |

Acid exposure time (AET); Symptom association probability (SAP)

Outcome of PPI Cessation

Thirty-four (34%) participants discontinued PPI and 66 resumed PPI. Compared to the discontinued PPI group, participants that resumed PPI reported higher mean baseline RESQ-eD scores (17.8 (SD 11.7) vs 12.0 (9.6); p=0.02) and GerdQ scores (9.3 (4.6) vs 7.2 (3.0); p=0.01).

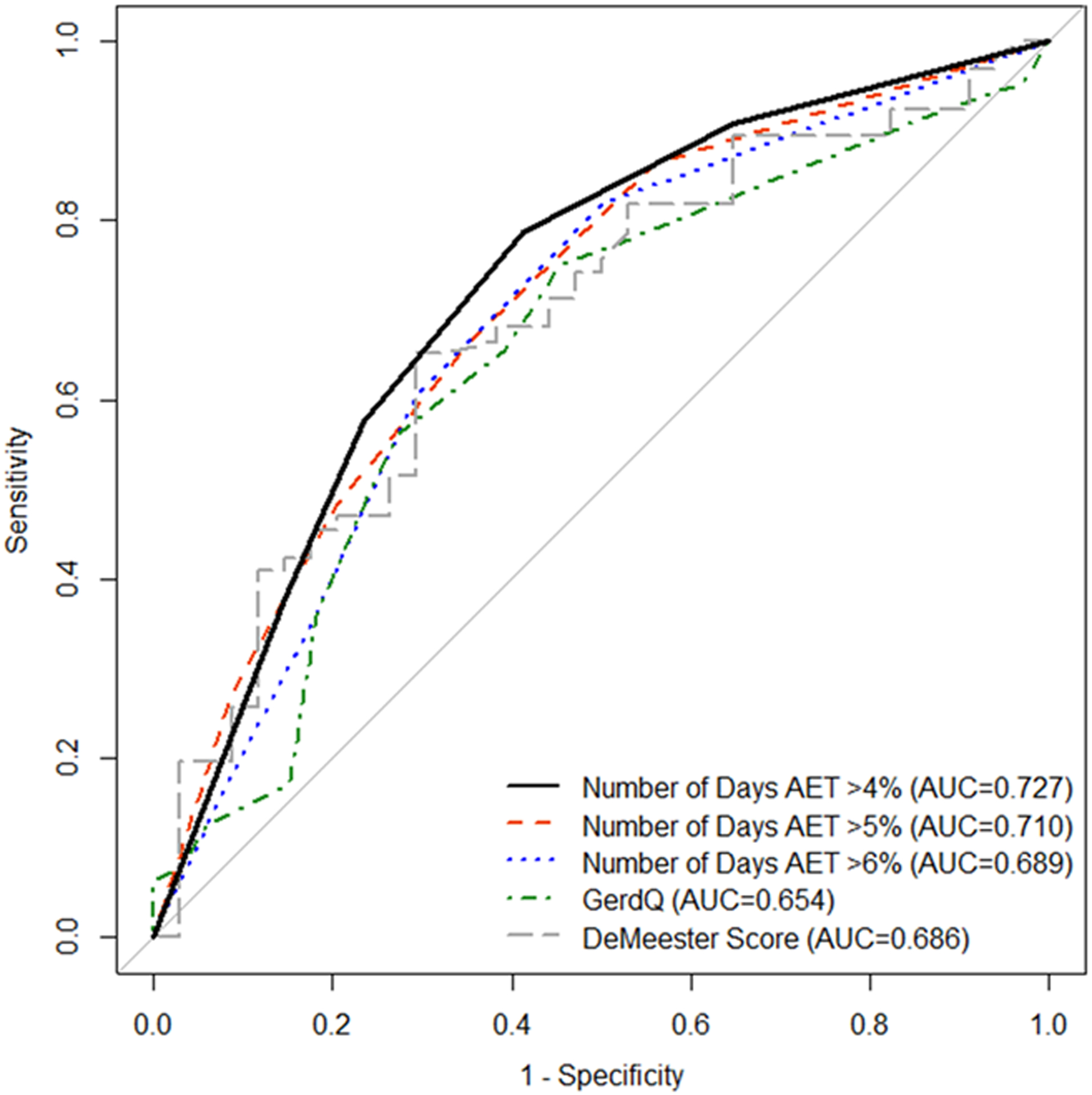

Primary Analysis: Association Between Reflux Monitoring and Outcome of PPI Cessation

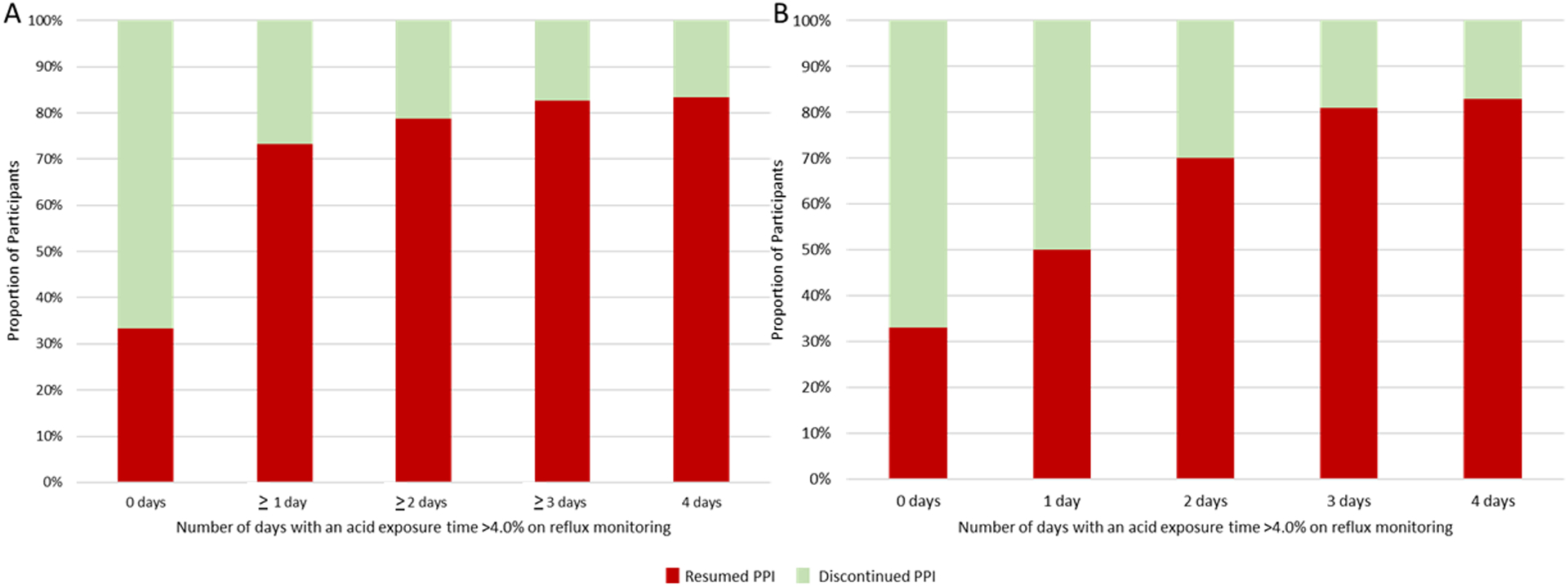

All reflux monitoring data were associated with outcome of PPI cessation. Total AET was significantly higher in the resumed PPI group compared to the discontinued PPI group (6.6% (SD 3.6) vs 4.3% (SD 3.6); p<0.01). The strongest predictor of PPI discontinuation was number of days with AET >4.0% in which every additional day with AET >4.0% was associated with a 1.8 increased odds of PPI resumption (OR 1.82 (95% CI 1.34, 2.56); p<0.01) with an AUC of 0.73 (95% CI 0.62, 0.83) (Figure 2). For instance, the odds of discontinuing PPI for participants with zero days of an AET >4.0% was 10 times greater than participants with AET >4.0% across all four days (OR 10.0 (95% CI 2.70, 43.32); p<0.01) (Figure 3). An AET >4.0% for 2 or more days maximized prognostic performance (OR 5.31 (95% CI 2.19, 13.44); p<0.001) with an AUC of 0.69, 79% sensitivity and 59% specificity for ability to discontinue PPI therapy. As such, in subsequent analyses below, objective GERD is defined as AET >4.0% for 2 or more days.

Figure 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristics for Outcome of PPI Cessation Intervention.

Figure 3.

Ability to Discontinue PPI Based on Number of Days with Elevated Acid Exposure.

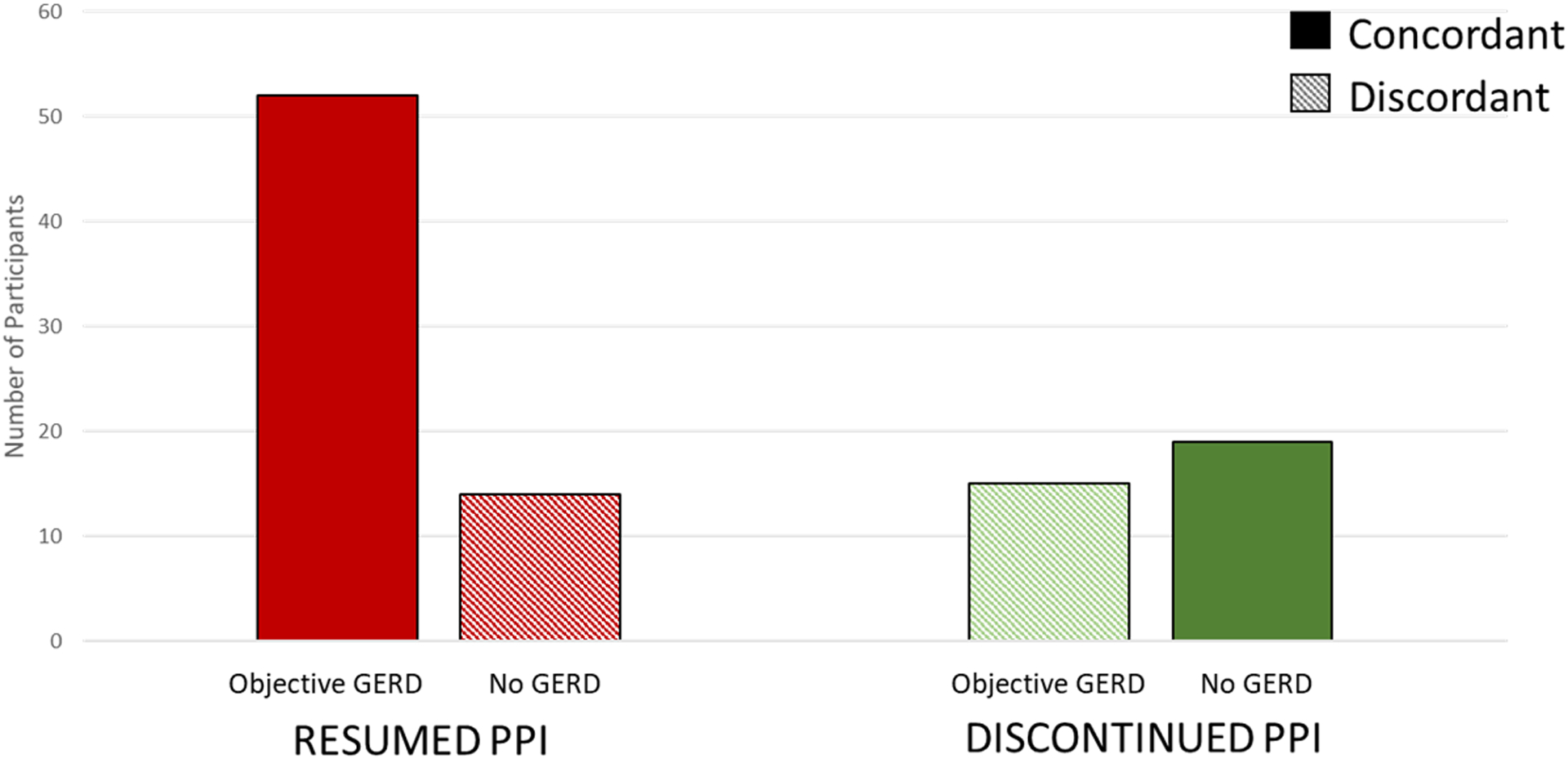

Figure 4 examines the relationship between outcome of PPI cessation (resumed or discontinued PPI) and results of reflux monitoring (objective GERD or no GERD). Overall, 71% of results on reflux monitoring were concordant with outcome (resumed PPI/objective GERD or discontinued PPI/no GERD). Among 29 discordant cases, 14 participants without GERD resumed PPI and 15 participants with objective GERD discontinued PPI, 7 (47%) of which had erosive esophagitis. Among the 14 participants with Los Angeles B esophagitis, 13 (93%) had objective GERD (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 4.

Agreement Between Reflux Monitoring and Outcome of PPI Cessation

Symptom Severity During Study Intervention

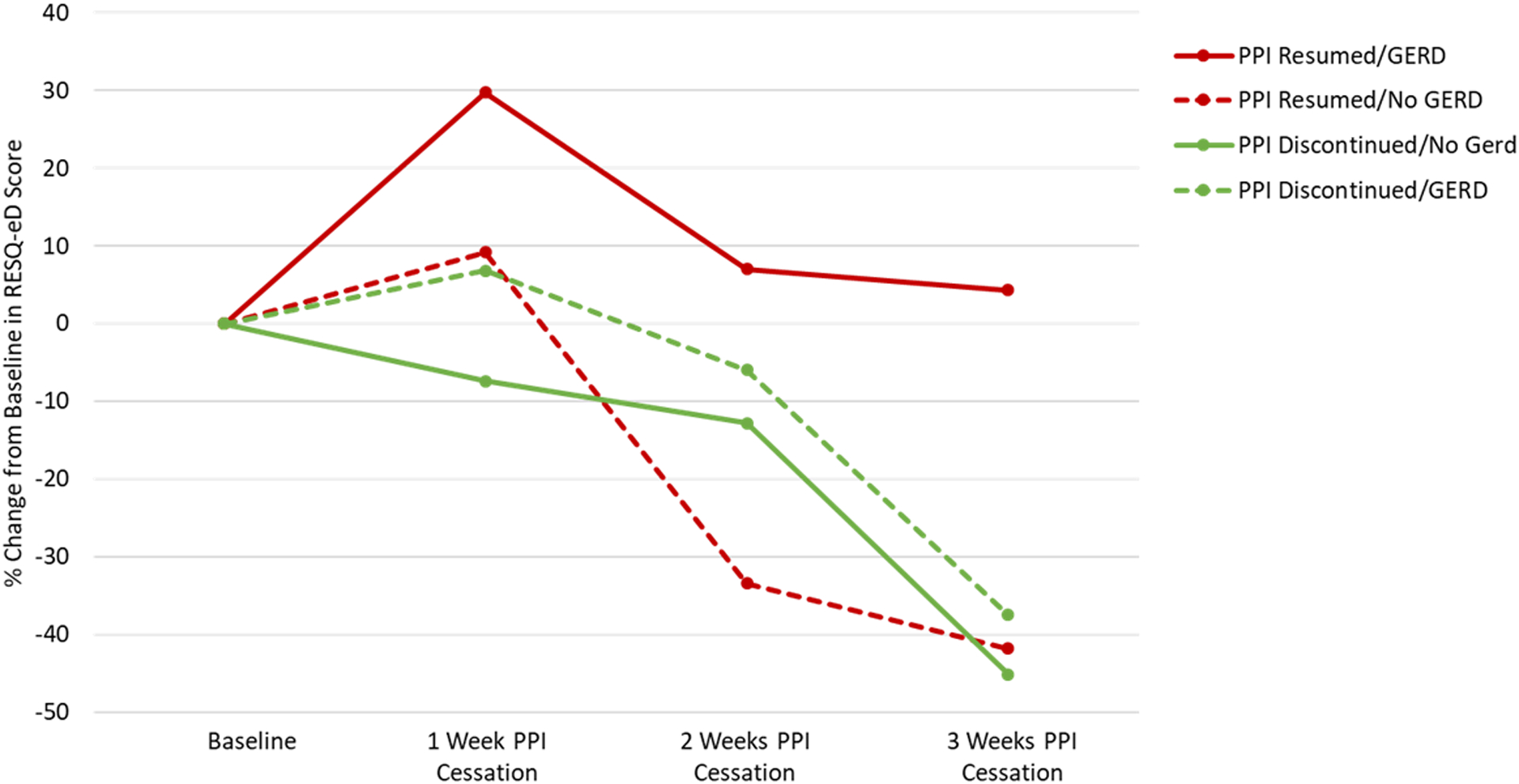

From baseline to end of intervention, the mean RESQ-eD score decreased by 19.8% (SD 78.8). The RESQ-eD decreased for all participant subgroups except those that resumed PPI and had objective GERD (Figure 5). Reduction in RESQ-eD was greater among participants with objective GERD compared to no GERD (−42.1% (49.3) vs −7.0% (SD 89.6); p=0.03).

Figure 5.

Patient Reported RESQ-eD Scores Throughout PPI Cessation Intervention

DISCUSSION

Inadequate symptom relief with PPI therapy among patients experiencing gastro-esophageal reflux symptoms is a common occurrence and contributes a substantial health care burden in terms of inappropriate PPI utilization, delay in appropriate management and health care costs. This is the first blinded prospective clinical trial to utilize relevant clinical outcomes, including ability to discontinue PPI therapy and symptom severity off PPI, to determine the utility of prolonged wireless reflux monitoring. Our results establish that prolonged reflux monitoring off PPI is clinically useful to guide the management of patients with inadequate PPI response. Of 100 participants, 34% tolerated PPI cessation throughout the study. Acid exposure time greater than 4.0% on reflux monitoring was an important physiomarker in predicting ability to discontinue PPI. Patients with negative wireless reflux monitoring, defined as 0 days with acid exposure time >4.0%, had 10 times the odds of tolerating PPI discontinuation compared to those with all 4 days positive. Overall, the threshold of 2 or more days of acid exposure time >4.0% was most predictive of the ability to refrain from PPI resumption. Patients that discontinued PPI also reported greater reduction in symptom burden compared to those that resumed PPI, however symptom scores alone did not predict which patients were able to discontinue their PPI therapy. Results from this study support the upfront use of prolonged wireless reflux monitoring to provide a personalized approach to the management of patients with inadequate PPI response.

Importantly, this study validates esophageal acid exposure as a reliable physiomarker of GERD and is the first to demonstrate the prognostic ability of acid exposure to predict response to PPI cessation.4, 17 The high negative predictive value of reflux monitoring observed in this study could translate to PPI discontinuation in over one third of symptomatic patients with inadequate response to PPI. This shift in management could have tremendous implications for patient care as well as health care utilization. Prior cost models estimate considerable cost saving with upfront prolonged wireless reflux monitoring compared to empiric PPI therapy, ranging between $1,048 to $15,853 per patient.18, 19 As such, findings from this study could conservatively translate to a cost-saving of $35,632 per 100 symptomatic patients with inadequate PPI response. While the concept of upfront reflux monitoring for inadequate PPI response is endorsed by the American College of Gastroenterology and American Gastroenterological Association, guidelines are based on very low level of evidence and expert opinion, and clinical practice frequently differs from societal recommendations.20–22 Our study is the first trial to demonstrate the clinical utility of upfront measurement of acid exposure to guide PPI management for the population with inadequate PPI response.

Further, this study highlights shortcomings of directing anti-reflux management based on patient reported symptoms or tolerance of PPI cessation alone. In this study, outcome of PPI cessation was incongruent with objective acid exposure in 29% of cases. Among 15 patients with elevated acid exposure who discontinued PPI therapy, 47% had erosive esophagitis on endoscopy. It is plausible that fear of long-term PPI use drove PPI discontinuation in this group of patients with erosive reflux disease.8 Nonetheless, it is well established that maintenance PPI therapy in erosive reflux disease reduces risk of progression to Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma.20, 23–25 Hence, reliance on patient reported symptoms or tolerance of PPI cessation alone without objective reflux monitoring data could result in deleterious outcomes. Further, while not considered conclusive for GERD in the Lyon consensus, this study highlights that Los Angeles B esophagitis is suggestive of objective pathologic GERD.

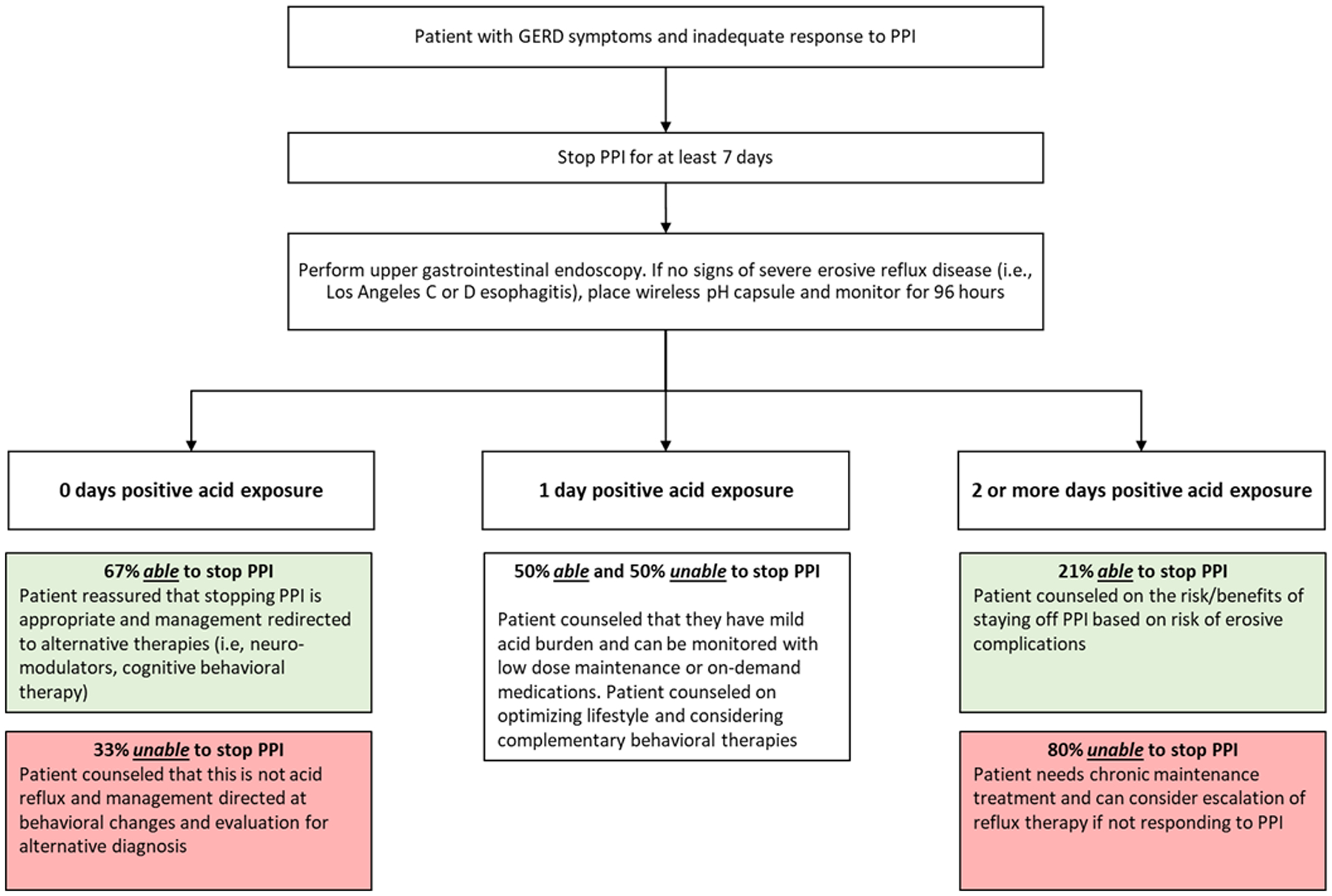

Figure 6 conceptualizes the implications of these results for the care paradigm of symptomatic patients with inadequate response to PPI therapy. Upfront prolonged reflux monitoring allows for phenotyping the patient and utilizing a personalized management approach.26 Patients with normal acid exposure over four days can be reassured on the appropriateness of PPI cessation with evaluation redirected toward alternative etiologies. The majority will be able to stop PPI without exacerbation of symptoms. In some cases, functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity may drive persistent symptoms, for which a growing body of literature and experiences support the efficacy of psychological interventions (i.e, hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic neuromodulation.4, 11, 12, 27–32 On the other hand, most patients with two or more days with elevated acid exposure will require ongoing acid suppression, and possibly escalation of anti-reflux management.33 Patients with mild elevation in acid exposure may demonstrate varying ability to stop PPI therapy. This group should be counseled that acid exposure is mild with therapeutic focus on lifestyle optimization, particularly weight management, complemented by behavioral or pharmacologic treatment as needed. For those unable to tolerate PPI cessation, on-demand or titration to lowest effective dose of PPI is reasonable.20, 34, 35 This conceptual model is based on clinical experience coupled with results from this study, and outcomes of a phenotype guided personalized management approach to GERD requires evaluation in a future phenotype stratified clinical trial. Further, predictors of PPI requirement should similarly be studied in a population with extra-esophageal symptoms such as dysphonia, sore throat, and cough since the patient population in our current study was limited to patients experiencing typical symptoms of reflux.

Figure 6.

Conceptual Paradigm of Diagnostic Evaluation and Management for Patients with GERD Symptoms and Inadequate Symptom Response to PPI Therapy

This study design attempted to address limitations inherent to this study. Given the potential of rebound gastric acid secretion within 7 days of PPI cessation, the duration of PPI cessation intervention was 21 days as symptoms typically return one week after discontinuing PPI and erosive esophagitis changes and inflammation present two weeks after discontinuing PPI therapy in erosive esophagitis healed while on PPI.36 This potential is also minimized since 75% of patients had been off PPI therapy for at least 10 days prior to their endoscopy. Lack of a placebo arm in this single-arm trial may introduce response bias among participants, however, this study aimed to determine symptom response during PPI cessation without knowledge of acid exposure as opposed to whether acid exposure could predict symptoms on acid suppression. Blinding the participant and study investigators to reflux monitoring data, and the external analyst to outcome minimized potential biases. Multiple measures were evaluated statistically, which increases the potential of a type I error rate. While the study was conducted at tertiary care referral centers, the results should be generalizable to health care settings that manage patients with symptoms of GERD. The clinician should be aware of practical limitations inherent to wireless and catheter based reflux monitoring including potential for misplacement of the wireless capsule and that exclusion of meals to avoid intra-meal acid exposure relies on patient reported mealtimes. Further, unlike catheter based impedance-pH monitoring, wireless reflux monitoring does not capture weakly or non-acidic reflux events, which risks potential for a negative wireless reflux monitoring study for a patient with non-acidic volume predominant GERD pathology.

In conclusion, this prospective double-blind clinical trial of 100 patients with inadequate PPI response highlights the strong association between acid exposure data measured on prolonged wireless reflux monitoring and a patient’s ability to successfully stop PPI therapy without symptom exacerbation. This study is the first of its kind to provide high-level evidence in support of early reflux monitoring off acid suppression in order to phenotype the patient with inadequate PPI response, and personalize care accordingly. A phenotype guided care approach for patients with suspected GERD and inadequate PPI response has tremendous implications for health-related quality of life and resource utilization associated with GERD.

Supplementary Material

Research Funding Support:

This study was funded by NIH R01 DK092217-04 (PI: Pandolfino)

Abbreviations:

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- PPI

Proton pump inhibitor

- RESQ-eD

Reflux Symptom Questionnaire electronic Diary

- AET

Acid exposure time

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- AUC

Area under curve

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

RY: Consultant: Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Diversatek; Research support: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; Advisory Board: Phatom Pharmaceuticals

CPG: Consultant: Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, Iso-Thrive, Quintiles

DAC: Consultant: Medtronic

PJK: Research support: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; Advisory Board: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals

MFV: Consultant: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Diversatek, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Daewood

Patent on mucosal integrity by Vanderbilt

JEP: Consultant: Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Diversatek; Research support: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Takeda; Advisory Board: Medtronic, Diversatek; Stock Options: Crospon Inc

MM, BDN, JT, AJ, LK, AK: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, et al. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731–1741 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900–20; quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delshad SD, Almario CV, Chey WD, et al. Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Proton Pump Inhibitor-Refractory Symptoms. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1250–1261 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized Trial of Medical versus Surgical Treatment for Refractory Heartburn. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1513–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G, Smout AJ. Management of the patient with incomplete response to PPI therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:401–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, et al. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foundation A American Gastroenterological Assoc - Treating GERD | Choosing Wisely. Volume 2020, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurlander JE, Kennedy JK, Rubenstein JH, et al. Patients’ Perceptions of Proton Pump Inhibitor Risks and Attempts at Discontinuation: A National Survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurlander JE, Rubenstein JH, Richardson CR, et al. Physicians’ Perceptions of Proton Pump Inhibitor Risks and Recommendations to Discontinue: A National Survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut 2018;67:1351–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdallah J, George N, Yamasaki T, et al. Most Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Who Failed Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy Also Have Functional Esophageal Disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1073–1080 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadlapati R, Tye M, Keefer L, et al. Psychosocial Distress and Quality of Life Impairment Are Associated With Symptom Severity in PPI Non-Responders With Normal Impedance-pH Profiles. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut 2010;59:714–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonasson C, Wernersson B, Hoff DA, et al. Validation of the GerdQ questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:564–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vakil N, Bjorck K, Denison H, et al. Validation of the reflux symptom questionnaire electronic diary in partial responders to proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2012;3:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Parameters on Esophageal pH-Impedance Monitoring That Predict Outcomes of Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:884–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afaneh C, Zoghbi V, Finnerty BM, et al. BRAVO esophageal pH monitoring: more cost-effective than empiric medical therapy for suspected gastroesophageal reflux. Surg Endosc 2016;30:3454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WC, Yeh YC, Lacy BE, et al. Timely confirmation of gastro-esophageal reflux disease via pH monitoring: estimating budget impact on managed care organizations. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1317–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:308–28; quiz 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1383–1391, 1391 e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gyawali CP, Carlson DC, Chen JW, et al. Esophageal Physiologic Testing American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh S, Garg SK, Singh PP, et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2014;63:1229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G. Failure of reflux inhibitors in clinical trials: bad drugs or wrong patients? Gut 2012;61:1501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:30–50; quiz 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yadlapati R, Pandolfino JE. Personalized Approach in the Work-up and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2020;30:227–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riehl ME, Chen JW. The Proton Pump Inhibitor Nonresponder: a Behavioral Approach to Improvement and Wellness. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2018;20:34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickman R, Maradey-Romero C, Fass R. The role of pain modulators in esophageal disorders - no pain no gain. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon RO 3rd, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.You LQ, Liu J, Jia L, et al. Effect of low-dose amitriptyline on globus pharyngeus and its side effects. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:7455–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman S, Keefer L, Imam H, et al. Majority of symptoms in esophageal reflux PPI non-responders are not related to reflux. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2015;27:1667–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riehl ME, Kinsinger S, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Role of a health psychologist in the management of functional esophageal complaints. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gawron AJ, Bell R, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Surgical and endoscopic management options for patients with GERD based on proton pump inhibitor symptom response: recommendations from an expert U.S. panel. Gastrointest Endosc 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gyawali CP, Fass R. Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:302–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yadlapati R, Pandolfino JE, Alexeeva O, et al. The Reflux Improvement and Monitoring (TRIM) Program Is Associated With Symptom Improvement and Weight Reduction for Patients With Obesity and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunbar KB, Agoston AT, Odze RD, et al. Association of Acute Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease With Esophageal Histologic Changes. JAMA 2016;315:2104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.