BACKGROUND

NONMEDICAL OPIOID USE AND DRUG INJECTION IN THE U.S. AND RURAL AMERICA

The modern American crisis in nonmedical use of opioids—including prescription painkillers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—highlights interweaving failures in healthcare policy and public health prevention (McCarty et al., 2018). There were 46,802 opioid-related deaths in 2018 in the U.S.—nearly five times as many at the start of the century —with more than 26% of these deaths involving a prescription opioid (N. Wilson, 2020). Although there have been increasingly tighter production regulations have been placed on the pharmaceutical industry, auspicious prescription drug monitoring programs, and broadly implemented, evidence-based public health campaigns, various fissures continue to contribute to the nation’s ongoing opioid crisis and broader challenges—for example, in employment, housing, education etc.—faced by the population of people who use drugs (PWUD) nonmedically (Corrigan & Nieweglowski, 2018).

The opioid crisis is especially pronounced in rural areas, where a confluence of systemic factors, such as a fragmented healthcare system, and social forces, including economic stress and community attitudes, may work to both propel and sustain usage (Bolinski et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2019). Further, rates of drug injection, specifically of opioids, has increased in rural areas (Bruneau et al., 2019; Lerner & Fauci, 2019), intensifying the risk of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDs and Hepatitis C. Stigma related to nonmedical drug use negatively impacts mental and physical health and overall treatment outcomes (Wakeman & Rich, 2018). Presently, little research exists—accounting for America’s unique, modern opioid usage tapestry—examining attitudes on nonmedical opioid use in rural environments (Bolinski et al., 2019). This research gap has thus foreclosed a more lucid understanding of how stigma might impede efforts to stem the current crisis. We attempt to address this gap by assessing views on nonmedical opioid use in rural southern Illinois.

The broad, accelerated patterns of nonmedical opioid use in rural areas such as rural southern Illinois are linked with reduced employment opportunities and a higher density of physically-demanding jobs, such as those in the fields of agriculture and coal mining, which may contribute to chronic pain and opioid prescribing (Thomas et al., 2019). Other factors associated with the rural opioid surge include limited access to healthcare and opioid use disorder treatment (Rigg et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2019). Less studied has been the impact of potentially regressive local attitudes on drug use and harm reduction programming (Keyes et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2018) which we investigate here utilizing a stigma-focused typology, the FINIS (Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma) (Pescosolido et al., 2008).

STIGMA AND NONMEDICAL OPIOID USE IN GEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXTS

For Goffman (Goffman, 2009), stigma was a disenfranchising dynamic or process inclusive of a specific attribute (e.g., a physical marker on the body such as a tattoo) or behavior that situated a person outside of the “norm,” galvanizing the public to view this person as less desirable. In rural areas, stigma against certain atypical individual features or tendencies may generally be more elevated as a consequence of misunderstandings, residents’ limited interactions and restricted information diffusion (Havens et al., 2011), or may simply be due to residents’ resistance to “neutralizing” information—factors which might otherwise confer stigmatizers with a degree of sensitivity or empathy. Relative religious, racial/ethnic and cultural homogeneity often typifying these rural communities that reduce exposure residents may have to “different” people and lifestyles may amplify stigma patterns (Whitehead et al., 2016).

Due to rural areas’ low or condensed population densities, residents’ networks may also be more consolidated and monolithic. Individuals with stigmatized markers may feel more isolated, both morally and criminally policed (Moore & Fraser, 2006), and therefore be less likely to disclose their status or seek support (Fadanelli et al., 2019; Larson & Corrigan, 2010). Indeed, research reveals how stigma depletes access to resources, affects multiple disease outcomes through multiple pathways, and is linked to poorer overall health (Phelan et al., 2014). Substance use stigma is severe and potentially more deleterious than other stigma forms. For example, in a study where participants were read vignettes about PWUD, people who smoke tobacco, or people with obesity, participants were more likely to “distance” themselves from PWUD (Phillips & Shaw, 2013). Other work has demonstrated that PWUD were viewed as more responsible for their condition (i.e. “deservedness”) and dangerous than persons with a mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2009; Muncan et al., 2020). Incorporating interviews with professional stakeholders and PWUD, we investigate how attitudes toward PWUD may foment a broader atmosphere of othering and disenfranchisement for PWUD living in rural southern Illinois.

CONCEPTUAL APPROACH: THE FRAMEWORK INTEGRATING NORMATIVE INFLUENCES ON STIGMA (FINIS)

Although recent research has been conducted on community-level attitudes on drug use and harm reduction (Brown, 2015; S. R. Friedman et al., 2017), this literature has not yet comprehensively considered the modern culture of opioid usage, much of which is associated with prescription opioids (rather than heroin), and contemporary perspectives around syringe exchange programs (SEPs), medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and novel opioid overdose reversal agents such as naloxone. Moreover, this literature has mostly neglected the potentially intricate social, cultural and policy dimensions of drug use, treatment and prevention in rural areas, and how stigma may operate and interact within and across these dimensions to create potentially hostile and unhealthy environments for PWUD.

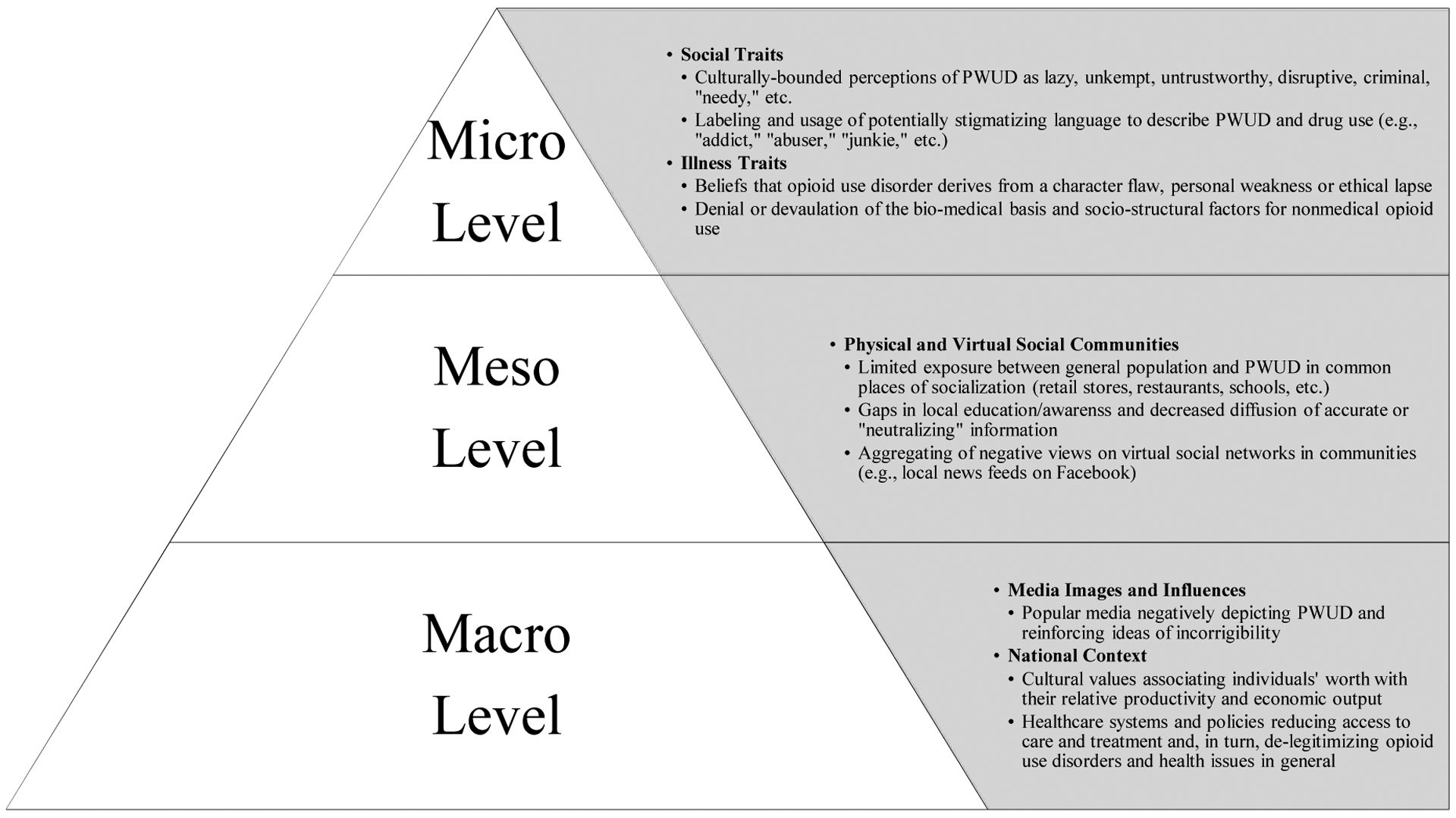

To address these existing limitations, we used the FINIS as a conceptual guide (Pescosolido et al., 2008). According to the FINIS, normative expectations manifesting during the stigmatization process occupy multiple levels of socialization, including “micro or psychological and socio-cultural level or individual factors; meso or social network or organizational level factors; and macro or societal-wide factors” (Pescosolido, Martin, Lang, & Olafsdottir, 2008: 433). These levels operationalize in the form of labeling, stereotyping, othering, status loss and discrimination (Link and Phelan, 2001). At the micro level, PWUD’s social traits (age, class, social distance, etc.) related to status and illness traits (culpability, “contagion” risk, etc.) converge to shape the identification and evaluation of PWUD (Phelan et al., 2014). At the meso level, stigma manifests in interactions (intentional and not) between the labeled or “marked” PWUD and “unmarked” the general population in retail stores, restaurants, public spaces, etc. (Scott, 2018). At the macro level, popular media (TV, newspapers, social media, etc.) and national institutions with power and status may transmit, or fail to counter, negative PWUD depictions (McGinty et al., 2019). Key to the FINIS is the understanding that stigma operates within the complex interplay of community and individual-level factors. Thus, the categories we present are disaggregated for theoretical purposes, but are, in actuality, intertwined and often difficult to untangle.

Guided by the FINIS, we conducted semi-structured interviews with various professional stakeholders, and PWUD, in rural southern Illinois, to investigate and contrast perspectives related to PWUD, nonmedical opioid use, treatment, and harm reduction. Professional stakeholders, such as law enforcement, clinicians, and social workers, often constitute a primary interface for PWUD, routinely crafting and enforcing policies which dramatically affect PWUD treatment and care (Does et al., 2017; Pergolizzi Jr et al., 2018). Sparse research has been conducted, in the present context, with professional stakeholders, making research on them vital to improving our understanding of actors associated with the opioid crisis response. Accordingly, the current analysis may provide valuable insights which professionals and (would-be) advocates can use to combat stigma sources and establish effective primary/secondary prevention efforts for nonmedical opioid use in rural areas.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Setting and Sample

The Delta Rural Health Study (DRHS) is a mixed methods research project focused on contextualizing and understanding patterns and drivers of nonmedical opioid use in the rural, southernmost region of Illinois, or the Illinois Delta Region. This “hotspot,” bordering Missouri to the west, Indiana to the northeast, and Kentucky to the southeast, contains roughly 330,000 individuals across 6,000 square miles. Rural areas in these neighboring states, like those in southern Illinois, face outsized challenges in addressing their distinctive, yet overlapping, opioid crises (Dombrowski et al., 2016).

As part of the DRHS initiative, semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted in 16 southern Illinois counties with various professional stakeholders and a sample of PWUD. To account for and understand the broad array of stakeholders whom encounter PWUD in the course of their professional duties, we recruited from a broad constellation of stakeholder groups, including local law enforcement offices; healthcare and drug treatment entities; emergency medical services (EMS); courts; and community-based organizations.

To participate, stakeholders had to be >18 years old, employed by one of the aforementioned entities and have at least some exposure to clients/patients etc. whom were PWUD. Additionally, we interviewed PWUD in the region; this sample helped theoretically situate and contextualize commentary from the stakeholders, and vice-versa. Eligibility criteria for PWUD included: > 15 years old and used any opioid non-medically by any route in the past 30 days or injected any drug, including opioids in the past 30 days.

Procedures

The DRHS interviews were conducted in-person between June 2018 and February 2019 by interviewers trained in qualitative methods. Participants were paid $40 for their time. Interview questions sought to characterize factors associated with attitudes and behaviors in relation to PWUD and nonmedical opioid use/drug injection. Other interview topics addressed respondents’ perceptions on harm reduction strategies (e.g., SEPs) and MOUD, such as buprenorphinenaloxone (Suboxone®), a partial opioid agonist used to treat opioid use disorders, and naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal medication.

Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted roughly one hour. Following each interview, the interviewer created an observational memo outlining key perceptions, prominent topics, and respondent dispositions (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007). Interview audios were professionally transcribed and then cleaned and coded using NVivo 12 (Melbourne, Australia).

Analysis followed an inductive approach, in accord with the FINIS (Pescosolido et al., 2008). Specifically, following a close reading of the transcripts and determination of general organizational domains using conceptual anchors screened from the interview guide and the FINIS, a provisional codebook was developed. Codes were systematically refined. To establish a measure of consistency, the primary coder (XX) and a second coder (XY) coded a subset of transcripts (n=5) and exchanged suggestions where appropriate. Additionally, member-checking, the process of confirming emergent findings through consultation with “insiders” (Carlson, 2010), was conducted with existing participants and members of the DRHS Community Advisory Board to bring greater interpretive precision. All DRHS procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Chicago. Consent was obtained from all participants.

FINDINGS

A total of 52 participants, including 30 professional stakeholders and 22 PWUD, were interviewed. The stakeholder sample was 53% male and 93% White, and comprised individuals working in local healthcare entities and hospitals (n=8), drug treatment facilities (n=6), law enforcement and probation offices (n=4), health departments (n=4), community and faith-based organizations (n=3), courts (n=2), and EMS (n=2). Stakeholder participants held a range of positions within their respective organizations, including roles in leadership/management, administration, outreach, and direct services. Given the few organizations and professionals engaging the PWUD population in the study area, no additional, potentially-identifying details are provided to protect participants’ identities. Of the 22 participating PWUD, 14 (63.6%) were male and 20 (90.9%) were White. The average age of PWUD (± SD) was 36.4 years old (± 8.7), with an age range of 25 to 60 years old. Further, most PWUD had a high school diploma or less (54.5%) and received public assistance (77.3%). Most PWUD used multiple drugs, or engaged in polydrug use, including opioids as well non-opioids, such as crack and amphetamines. Pseudonyms are used to relay the narratives of participants. PWUD are further identified by their age, race and gender.

Briefly, themes were bracketed around the following three dimensions of stigma as associated with FINIS (Figure 1); Micro-level: Personal perceptions of PWUD and nonmedical opioid use; Meso-level: Community operationalization of stigma against PWUD and nonmedical opioid use; and Macro-level: Professional and community stigma relationship with prevention and treatment systems.

Figure 1.

Applying the FINIS to Assess Influences behind Perceptions and Behaviors toward Nonmedical Opioid Use

1.Adapted from Pescosolido et al., 2008

MICRO LEVEL: PERSONAL PERCEPTIONS OF PWUD

THE PERCEIVED MORAL AND CHARACTER FLAWS OF PWUD

Stakeholders offered mixed impressions on opioid use and PWUD in their respective communities and the broader southern Illinois region, often situating this discussion in terms of morality and character, and labeling PWUD due to their perceived social traits and opioid use traits (illness traits). Opinions were typically drawn and articulated using fungible distinctions between PWUD, as individuals, and the individual act of using opioids. As Marvin, the director of a pain clinic, demonstrates:

“Nobody typically says, ‘I’m gonna get addicted today.’ It happens rather insidiously. So, it’s not a character flaw that people’s respond to these drugs a certain way. It’s not ‘cause you chose it, or you’re a bad person; or ‘Oh, those damn addicts!’ These are real human beings with this physiology in the brain going on that is like an illness.”

Unsurprisingly, compared to other stakeholder groups, healthcare providers more commonly invoked the biomedical basis for drug use (i.e., that the etiology of drug use is largely biological or genetic in nature) versus a strictly sociocultural explanatory model. Although the biomedical model, which gave way to diagnosis of “substance use disorders,” has benefited PWUD by opening avenues for treatment, there may be unintended consequences. For example the model’s focus on individuals (and individuals’ responsibility for help-seeking) often negates larger structural issues, such as limited access to healthcare, that place PWUD at risk for negative health outcomes (Sturmberg & Martin, 2016).

Potentially stigmatizing labels for drug use (Kelly et al., 2016)—terms like “addict,” “abuser,” “pill-popper,” and “dirty” (as in opposition to “clean,” unsullied), etc.—appeared throughout the interviews, among both stakeholders, in characterizing PWUD, and PWUD, in some cases, characterizing themselves and other PWUD. Frank, a pharmacist who described himself as a PWUD advocate, illustrates this dichotomy, noting, “The old adage is that there’s a moral slash character flaw of addicts that they can stop using and abusing drugs whenever they want to, is wrong. The brain imaging that we can show nowadays is highly proficient at showing that alcohol, drugs, opioids, even marijuana, affect the brain.” As Frank further illustrated, stereotypes about what constituted common PWUD markers still colored and tempered the dispositions of even advocates:

“There are those patients that throw up [my] red flag the minute they walk in the door; there are certain drug-seekers who have distinguishing characteristics—primarily, tattoos, earrings. All the things that you’re told by the public media that you’re not supposed to do because it’s stereotyping is actually protecting my pharmacy license; because, if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s probably a duck. […] Everybody in the store behind the [pharmacy] counter knows why they’re wanting to buy some needles; not because they’re diabetic. And so, just initially, that knowledge and that stigma comes to the front immediately. ‘Is it right?’ ‘No.’ But it’s just human nature.”

In the above quote, Frank describes identifiable markers (and behaviors) on persons that lead him to label them as substance users, indicating that he then reflexively makes assumptions about the perceived ‘drug-seekers’. Frank perceives the stereotyping of PWUD as mere ‘human nature,’ while discussing the tension presented by media’s anti-stigma bent. This idea, that stereotyping is a deep-rooted part of human nature, showcases a belief on stigma’s purported inevitability (Bogdan & Taylor, 1989) and is deepened by Frank’s suggestion that stereotyping was incidentally a protective and preemptive act necessary to maintain his pharmacist license. This, and the chasm in appropriate, or “politically correct,” drug use language (Carroll, 2019), further reflects a broader process of separation (Link & Phelan, 2001).

Interestingly, many PWUD we interviewed adopted similar vernacular to describe themselves. Dale, a 39-year-old White male who said he injected opioids and methamphetamine, explained his challenges navigating what he perceived as a biased court system, noting “I know how to go about filing motions and everything else—just because I’m a meth-head don’t mean I’m not smart.” Like most other PWUD we interviewed, Dale also frequently referred to himself as an “addict,” seemingly internalizing this typology while also combating projections on its social meaning, inferring that this language was commonly used by institutions to describe PWUD. This dynamic is further discussed in the next section.

PROBLEMATIZING THE CAPACITY AND WILLPOWER OF PWUD

Some of the more cutting and adversarial perceptions on nonmedical opioid use and PWUD came from law enforcement officials, EMS workers, and probation officers. These dispositions appeared to partially arise from the relative frequency and intensity of their PWUD encounters, which typically occurred during stops and arrests for suspected criminal activity, and emergency overdose calls, etc. This dynamic aligned with other recent research on first responder burnout (Pike et al., 2019) and recalls Hughes’ idea of “dirty work” (Hughes, 1962). For these stakeholders, normative values such as “picking yourself up by the bootstraps” were particularly salient. Zachary, a long-tenured sheriff, explained the following, stressing that his views resonated with most of his local law enforcement colleagues:

“I look down on [PWUD]. I wish I didn’t; I try not to. I try to be a good Christian, and I try to be an empathetic individual. […] It’s just exhausting and draining, and a lot of the times I don’t feel like what we’re doing is worth it. […] I just don’t see how life would ever be that bad. To me, it’s just simple; quit doing drugs, clean up your act, get a job, use that job to better your education, use that education to better your job.”

These attitudes on the preventability of drug usage, and PWUD’s sensitivity to their existence, may have consequences. In describing her experience interacting with police and EMS during several overdose episodes, Bethany, a White 31-year-old female who reported using heroin, warned that, “More people end up hurt because they don’t wanna call the law. Because they know they’re just gonna fuck with them. They’re just gonna treat them like shit, like drug addicts.” This viewpoint, enlivened by the commentary of clinicians we spoke to, shows how PWUD perceptions of being proscriptively labeled and positioned may make them susceptible to mistreatment and, in turn, healthcare disengagement.

Vanessa, a clinical treatment manager for PWUD, observed the following scenario as common, emphasizing the frustration and resignation that clinicians may experience in working with PWUD:

“The doctor wants to get out of there as quickly as possible; maybe the [PWUD] has bad hygiene, maybe they’re being disruptive. […] Clients who we have go to the doctor’s office with [are] more likely to be seen as noncompliant: ‘Oh, well you’re not going to follow my recommendations anyway, I’m not going to bother helping you or prescribing you with this because I know your history is you’ve never done that. I’ve suggested this, this, and this. You never follow through; you don’t take your medication.’ So, I think that they’re stigmatized, and I think because of that they receive less good care.”

This statement, illustrating the internal justifications for discriminating, highlights the arc of weakened cultural health capital—i.e., trust, empathy and effort from clinical professionals (Shim, 2010)—and status loss that PWUD may incur in clinical settings. Nevertheless, as Vanessa alludes, factors contributing to stigma and discrimination, two distinctive forces, have cross-cutting dimensions: that is, drug use may be believed to correspond to other specific individual features (e.g., hygiene, behavior, etc.) which may be equally, or perhaps even more, abhorred and consequential in the enactment of stigma or discrimination. Thus, negative views of PWUD may reflect an amalgamation of negative views on one’s drug usage trait which simply reify negative views on traits thought to cascade or be borne from one’s drug usage.

As Benjamin, a hospital director, explained, clinicians’ feelings of frustration and futility were especially palpable, and seemingly unavoidable, in exchanges with suspected or known ‘drug seekers.’ Here, stigma may organically propagate in response to cues a PWUD gives off through “aberrant” behavior: “One of the most frustrating things can be when [PWUD] paint a picture before you go in and say ‘This is our drug-seeker.’ Sometimes, I’d rather not know until afterwards. […] You can reel it back 90%, but you’ve already colored that picture a little bit.” Benjamin further noted: “It doesn’t matter who they are and what they look like or anything. You’re going to think a little bit differently about them. It changes. You’d see it the most when physicians are tired and busy. […] It just depends on if they gave [you] Snickers before and they treat [you] nicely. ‘Why is he here?’ ‘Why are you messing with the system?’ ‘Why are you bogging down the system? It’s costing taxpayer dollars.’”

While recognizing stigma’s situational dimension (i.e., stigma may not be enacted when a clinician is in good spirits), multiple respondents perceived the source of this broader orientation as more fixed. Kerry, a 43-year-old White male who reported injecting opioids recounts his experiences receiving substance use treatment at various regional hospitals: “Over the years, I have been looked down on because I was an addict, and [I was] treated different in a hospital. I don’t think that’s right. Your job is to treat the problem, but you had so many addicts going in there and trying to work the system to get free pain pills […] that makes it look bad for the people that actually kind of need them.” The contrasting commentary from Benjamin and Kerry—who partially sympathizes with vigilant clinicians but advocates finely separating treatment of his condition from treatment of him as a patient—speaks to the commodification of the person (the patient), highlighting the clash of social pathologizing and economic incentivization in the American healthcare system (Timmermans & Almeling, 2009).

The interviews revealed multiple facets of stigma emanating from the micro-level–colorful labels, poignant stereotypes, and a separation of “us,” the hardworking and upstanding, and “them” the irresponsible, difficult and parasitic drains on our time, energy and resources. Here, status loss was evident in views of PWUD as less deserving and through signals of professionals’ inclination to freely exclude or discriminate against PWUD. Vitally, these dynamics highlight the degree to which stigma attitudes are constructed from, or on top of, a broader distaste for individuals deemed unkempt, unruly etc. (i.e., deviant and outside of the “norm”), perceptions which vary widely across class and culture (Speltini & Passini, 2014).

MESO LEVEL: COMMUNITY OPERATIONALIZATION OF STIGMA AGAINST PWUD AND NONMEDICAL OPIOID USE

SMALL TOWNS AND BIG RUMORS

Respondents felt residents in their respective communities harbored at least some angst towards PWUD. This dynamic was described as being broadened and deepened due to contracted population densities in their respective communities and the sense that “everyone knows everyone.” As Darryl, an EMS supervisor argues, “If somebody is labeled an addict, then this is Small Town, USA; this is the heart of the heartland, here: So, I don’t wanna come off and say we’re judgmental here, but it’s too small of an area. If Jack Smith’s an addict today—Jack Smith’s probably gonna be an addict 20 years from now, in some people’s eyes.” Further highlighting how rurality shaped the extent to which PWUD could otherwise avoid public scrutiny for their actions or achieve anonymity (Stewart et al., 2015), Darryl observes:

“It’s not like in New York City, or Chicago, where you tuck around the corner and no one really knows who you are. Around here, people know who people are; and you get arrested, your mug shot or whatever, it’s gonna go in the paper. When you only have [a certain number of] people living in an area, ‘Oh, yeah, I know Jack Smith. Yeah, I’ve heard of that guy before, blah, blah. Isn’t he from so-and-so? Oh yeah: He’s a doper.’”

This commentary illuminates how, in rural settings, as compared to urban or even suburban settings, available information about certain individual attributes may be more binary in nature and more easily penetrate and spread across residents’ networks. In turn, stigmatizing labels may become harder to dodge (or dislodge) and, once applied, harder to shed (Larson & Corrigan, 2010).

Claudine, a mental health counselor, corroborated Darryl’s sentiment, while emphasizing how social media operated in her small community context by contributing to the efficient genesis and spread of stigmatizing narratives: “It’s a small town, so if you’re arrested, it’s put in the paper. They put the arrest reports on Facebook. Facebook has a lot of gossip. So, I think that once you get that reputation, it’s really hard, especially if you have charges; you can’t work lots of times.” Alec, a 33 year-old White male who described a history of using oxycodone and heroin, mirrors this point, expressing difficulties finding a job due, in part, to his past convictions: “These two felonies are kicking my ass because they had it plastered all over the news that [I was a felon] and shit. This ain’t a very big town, so, it’s rough.” The framing of these real world and virtual spaces as reactionary and unforgiving further speaks to the recurrence or permanence of stigma (Ezell et al., 2018), highlighting the multiple communities that PWUD must traverse and how information flow in these spaces can curb fulfilment of one’s basic needs (e.g., employment, housing, education, etc.). Importantly, negative attitudes towards PWUD often operate through criminalization ideology which, in turn, is facilitated through proxies of discrimination according to race, class and status (Fraser & Moore, 2011; Keane, 2009)—as seen, for example, in America’s War on Drugs.

STIGMA GRADIENTS AND STIGMA BINARIES

Multiple respondents, like Claudine, argued that community views on drug use were often dependent on the specific drug being used, emphasizing how status loss may further deepen based on drug usage characteristics: “If you inject, you’re the worst of the worst, and it’s not too much longer before they ‘go down’ fairly quickly.” Some, however, saw a silver lining to this hierarchy, while acknowledging contradictions. For example, Wendy, a health department official, explained how methamphetamine use and drug injection remained highly stigmatized in her community, while opioid use was slowly being normalized in media, thus making it a less stigmatized drug: “The media puts out [information and] I think the person’s perception of a meth (methamphetamine) user is, ‘Yuck! Trash! You’re low class,’ and basically disgusting. Whereas a person who becomes opioid-addicted or dependent, ‘It’s not their fault.’ So, blame is diverted from that person.” Nevertheless, Wendy and most other respondents agreed that all types of nonmedical drug use—and all administration routes—were viewed unfavorably by community members. These attitudes may persist even within and between individual drug use communities. As Alyssa, a 38-year-old Black woman who reported opioid and crack use, explained, “The only thing different in snorting powder and smoking crack is the baking soda to ‘rock it up.’ ‘So, you callin’ me a crack-head when you are a powder-head?’ If you smoke premios (cigars), they think they are better; they think they are elite. And then the heroin and ecstasy, they have their own little circle, just like everywhere else. [And] the coke-heads think they are better [than heroin users].”

Throughout the interviews, multiple respondents highlighted a unique role for community-based organizations, such as faith-based organizations, in identifying and addressing this kind of network-bounded stigma. Simultaneously, respondents described barriers in tackling stigma present within these fields and among their colleagues. As Debra, a pastor, indicates, broader religious dogma around the morality of drug use was elevated among other pastoral leaders in the region and contributed to a stigmatizing atmosphere in local church networks:

“I’m not as typical for pastors here. I see opioid addiction as a medical issue, not a sign of spiritual weakness or ethical fault or something. Most people who are addicted are people who got that way without kind of realizing what they were doing with legal prescriptions and then, you know, falling down the rabbit hole […] Something came up at the ministerial [group] a couple months ago about a local politician who had a DUI, and several of the pastors there were like, ‘Well, I’ll never vote for him again,’ and so I think there are definitely those who [believe] addiction is a moral failing.”

Here, Debra, highlighting her own potentially delicate position outside of the pastoral norm speaks to an implicit litmus test in religiosity which involves abstaining from opioid use. Debra further observed a “difference in education level and exposure to [harm reduction] ideas” among these faith-based leaders in explaining how socioeconomic factors and information gaps may help routinize drug use stigmatization in the region. Further, as she explains, being marked as an “addict” could easily precipitate associative leaps into one’s character and personal quality (or qualifications) which could, in turn, negate the otherwise laudable traits of the individual. Inverting sociological logic on the primacy of status in determining drug use acceptability (Galea et al., 2003), this view further suggests that one’s position in society may not act as a reliable buffer against stigma related to one’s drug use.

In terms of more broadly addressing community-level stigma, respondents offered measured guidance, focusing on a need to present the spectrum of “faces” of the opioid crisis. Debra explained that “The [community has] that misconception, and it’s just that evil, dirty person in the alley that’s using [drugs], and they are probably oblivious to whom is actually using syringes. […] So, we’re just going to bring all of these issues to the forefront to let our community know that we do have these concerns and that we need to break out of our bubble [in] thinking that it’s all well here.”

Overall, meso-level stereotyping and associated processes of othering appear to be consistent features of the surveyed region, initiated through networks that are at once highly connected and yet also discernibly uncoupled from broader evidence-based health information networks operating beyond the meso-level. As respondents demonstrated, these dynamics contribute to a climate where general help-seeking may be actively discouraged, and treatment thus made to appear undeserved. In response to this dichotomy, multiple respondents explained that this effort would need to elevate a broad directive to humanize PWUD, their experience and their needs.

MACRO-LEVEL: PROFESSIONAL AND COMMUNITY STIGMA RELATIONSHIP WITH PREVENTION AND TREATMENT SYSTEMS

HARM REDUCTION AS A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD

Respondents’ commentary suggested that they possessed largely positive attitudes towards general “clinic-based” opioid use treatment, though when harm reduction was framed as a form of treatment, support waned. The lion’s share of harm reduction-related stigma was angled at services such as SEPs, with stakeholders grappling with their passive goal to stave off infectious disease transmission and their more immutable goal of not “enabling” drug use. Perry, an ER physician remarks, “There’s something that is just a little repugnant about saying, ‘Here, let me help you out with that; let me help you do that really bad thing you’re doing a little bit safer… Why are we encouraging people to do this thing they shouldn’t do?’” Reluctantly, however, Perry acknowledged that, “If I’m being intellectually honest, if these folks are using anyways, it sure makes sense to have clean needles.” Echoing this about-face, Leo, a probation officer speaking on needle exchanges, emphasizes:

“I’m not too kind on it. To that part where it talks about getting the dirty needles off [the street]? Great. Do I think it could encourage IV use? Yes, just because they can smoke it or whatever, but now they go somewhere and grab a whole bunch of clean needles to go shoot-up themselves. I see it as a two-part: It’s making sure they have clean needles and that they’re using it among themselves and they’re changing out their dirty needles. But they’re still getting the needles. They’re still using the drugs… They’re just getting new needles for next time… the next party day.”

With a similarly fatalistic outlook—namely that harm reduction enabled and indeed streamlined nonmedical opioid use—multiple respondents also expressed misgivings about the usage of naloxone agents to reverse overdoses. Observations here often focused on resistance to the perceived public costs of providing naloxone. Calvin, a probation court administrator, emphasized the existence of broad community antagonism towards public financing of social and safety-net programs, adding that much of this discourse was aired on social media. Referring again to the overlapping of real and virtual communities in the stigmatization process cited by other respondents, Calvin explains:

“I would say that the perception is that people don’t deserve to receive Narcan; that they deserve to die. I mean, I see it played out on social media: Any time there’s a post about that kind of thing from a news source. And, especially if they know that the Narcan is coming from grant money, and they don’t believe their tax money should be used to save people who in their eyes are not worthy of saving. I mean, that is a debate that happens almost daily on social media, which is tragic.”

Of note, most interviews were conducted in communities where the annual household income was well below state and national averages. Not surprisingly, concerns over the financing of social supports and services, such as overdose reversal agents, were often recounted by respondents in resurgent populist terms focusing on PWUD deservedness, agency and economic fairness. Respondents’ narratives highlighted community members’ ideals of PWUD failing to be “productive” citizens. This ideology was frequently rendered in terms of individuals’ obligation to better, or at least maintain, the collective equilibrium through consistent employment, childrearing etc., acts articulated as the baseline properties of a respected and valuable community member (Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2005). Simultaneously, these arguments frequently spoke to the need to exercise great caution whenever taxpayers’ dollars were at stake. These sentiments around deservedness (discussed more in next section) further illustrated the broader public’s resistance toward being active in supporting or otherwise engaging PWUD, thus potentially creating denser patterns of separation between PWUD and the general population.

BALANCING BUDGETS AND MORALS

William, a police commander speaking to laws obligating Illinois police to carry/administer naloxone (Narcan®) (Public Act 099–0480, 2015) and the deservedness theme, explains:

“Police officers aren’t required by law to carry epinephrine for a child who is suffering an anaphylactic reaction to a bee sting, or oral or IV glucose, or IM glucagon for somebody who has suffered a diabetic episode. And these are things that were beyond their control; it’s just nature. So, I personally do not agree with us administering drugs with pretty much no recourse to get the funds back for people who are choosing to induce a medical emergency, and not for people who it’s beyond their control.”

Faye, a health department coordinator, uses similar economics-tinged argumentation in invoking an example from her personal life:

“… [one of my family members], for instance: She’s a diabetic, and she can’t get free syringes. But yet, the drug addict down the street can? And they can get free Narcan®? Why are they getting free stuff when I have condition and need the exact same thing? It’s not really fair. […] They’re trying to get the dirty needles off the street, but it’s not gonna happen. […] My theory: If you can afford the drug, you can afford a ten-cent needle.”

In both passages, the singular revenue-generation prerogative of America’s healthcare system is promoted. In turn, control of one’s health is paradoxically emphasized as a device which PWUD can consciously and conspicuously wield—and waste—but as something that we (the general population or a child needing epinephrine, etc.) can neither wield nor waste. Thus, control (or lack thereof) is situationally stigmatized and often justified through the invocation of perceived analogues to publicly-supported opioid treatment/overdose prevention resources; in their words, it was unfair that Narcan® was “subsidized” by government, while other public health and medical resources—implicitly for more deserving people—were not. Nonetheless, despite the fervor behind these either-or views, most respondents were supportive of “clinic-based” treatments such as MOUD, including methadone and buprenorphine. Of note, at the time of this study, there were fewer than five buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone®) providers in the southern Illinois region, which is substantially below the estimated number necessary to address local population health needs. As Benjamin illustrates, the low adoption of Suboxone®-prescribing in the region may be associated with concerns over costs and training expectations as well as a sentiment that Suboxone® was, for all practical purposes, an opioid equally worthy of ire:

“I personally am not at all interested [in being licensed for Suboxone®]. To get educated for it, I have to pay for it, which seems strange. Also, it’s a street drug, Suboxone®. I see patients come into the ER that abuse Suboxone®. When we do their urine drug screens, it’s methadone-positive or Suboxone®-positive. Why would you give somebody another street drug? I can give them heroin same as Suboxone®. They’re both street drugs that give them a high that they’re abusing, and they come in overdosed on.”

Oliver, a family physician certified to provide Suboxone®, helps contextualize this perspective, further illuminating the public’s and clinicians’ antagonistic views on MOUD:

“[PWUD] face stigma, not only because of their disease, but because of my treatment. There’s a huge misunderstanding of what I’m doing, and it’s still a commonly-held belief, even in the medical community—that what I’m doing is actually giving them [illicit drugs], I’m just like perpetuating their addiction in some sort of controlled manner. It’s like, ‘You’re not really sober unless’ they quit taking my medicine.”

Demonstrating the cultural embeddedness of this (counter-)argument and internalization of its logic, Claire, a 27 year-old White female who reported using opioids, explained that, Suboxone® “still giv[es] you the same effect that the opioids give you and you’re still getting high off of it. So, I don’t understand why all opioid addicts don’t just save their money and go up to get Suboxone®.” In this statement, Claire re-affirms a common position of the community’s anti-MOUD contingent, highlighting a perceived loophole in the opioid use treatment and broader American healthcare ecology, while couching her argument in an intuitively economic context..

DISCUSSION

Findings from this qualitative investigation with multiple professional stakeholder groups and PWUD indicate that stigma against nonmedical opioid use, drug injection and treatment/harm reduction is a large and multifaceted issue in rural communities. In alignment with the FINIS, this widespread stigma manifested at the micro, meso, and macro levels (Pescosolido et al., 2008), corresponding to different levels of labeling, othering, status loss, and discrimination. Professional stakeholder interviews conducted here, corroborated by PWUD interviews, indicate that professionals in rural communities with regular exposure to PWUD may possess attitudes which stand in stark contrast to bio-medical and sociocultural explanatory models for drug use and harm reduction principles (Keane, 2003; J. D. Wilson et al., 2018).

With this in mind, although nearly all respondents indicated that they were aware of the various explanations for nonmedical opioid use, their ultimate stance on the value, agency and deservedness of PWUD varied. Individuals working in professions such as first response may express a sense of futility over the notion that they “have little to no influence over prescribing practices” and thus “can only intervene in a criminal problem, but not to prevent the problem before it becomes criminal” (Green et al., 2013: 679). Substance use disorders often carry with them the singularity of being medicalized conditions that are criminalized in ways deemed both morally unjust and counter to socio-medical “rehabilitation” (Kolla & Strike, 2020). In rural communities like those assessed here, the substance use remediation milieu is saddled by both of these burdens and an implicit obligation to be fiscally neutral.

While aligning prior research on stakeholders’ views on opioid use (Green et al., 2013; Rhodes et al., 2006), the punitive and retributive mentalities presented here are unique in illuminating stakeholders’ vision of themselves as responsible not only for meting-out justice for drug crimes, but also being stewards of rural communities’ limited financial resources. It is worth noting that several studies have found harm reduction to be cost-effective in the context of reducing PWUDs’ HIV/AIDS risk (D. P. Wilson et al., 2015; Wodak & Maher, 2010). Studies outside of the U.S. have identified similar cost-effectiveness attributes in harm reduction programming (Kim et al., 2014; Li et al., 2012). Little, though, is known about the cost-effectiveness of harm reduction in reducing overdose episodes and in modulating related morbidity, a key consideration for future research.

Illustrating that stigma acts as a “bi-directional” force, our results indicate that one’s drug use activity may stir, or simply reflect, (existing) negative impressions of other individual-level traits, including one’s behavior, hygiene, etc.. Thus, divining the ultimate stigma source represents a complex act requiring interrogation of broader social and cultural attitudes on what is normal and acceptable; i.e., meaning-making in the context of intersectional stigma (Turan et al., 2019). Likewise, of note, both stakeholders and PWUD often used what have been regarded as potentially stigmatizing and adversarial labels (e.g., “addict,” “abuse,” “drug-seeking,” etc.) to characterize PWUD and opioid use. This dynamic tentatively suggests that efforts to shift the language used to describe drug use and users (Kelly et al., 2016) have not permeated these communities and indicates that these “old” descriptive labels do not, in the present, necessarily reflect stigmatizing or otherwise harmful attitudes or ideologies. Nevertheless, the stigmatizer’s actions need not be intended to be malicious to be otherwise perceived as such by the individual whom thus feels stigmatized (or discriminated against).

With this in mind, stakeholders frequently depicted PWUD as disruptive, unrefined society members who fail to make discernible contributions to society and—speaking most centrally in the context of economic output—siphon communal resources and monopolize taxpayer-funded services. The capitalistic undertones in the tenor of this discourse animates the process dignity denial of economically disenfranchised populations (S. Friedman et al., 2015). In predominantly working class and formerly manufacturing-centric areas—including rural communities and cities in post-industrial areas, such as the portion of the “Rust Belt” surveyed here—where rapid deindustrialization, agricultural sector downturns, or community disinvestment have been consistent features, negative perceptions of drug use (and PWUD) as forms of economic parasitism may be augmented.

Continuing, multiple respondents’ spoke to the centrality of social media as a fertile space for community education on local opioid use and prevention initiatives. Tailored messages, sensitive to the aforementioned semantic nuances, could be employed on channels like Facebook to disrupt stigmatizing narratives derived from the macro and meso-level—e.g., by explaining linkages between chronic pain from manufacturing jobs and opioid use, the potential public health and economic benefits of harm reduction, etc.

With this in mind, this analysis hints at ways in which stigma may be amplified in the at-once condensed and fragmented networks which characterize rural areas domestically and abroad (Thomas et al., 2019). These networks may exact dire socio-emotional and health consequences for these already precariously-positioned populations by intensifying socioeconomic stressors associated with drug usage and diminishing PWUD’s capacity or willingness to utilize vital emergency services and clinical resources (Corrigan & Nieweglowski, 2018). Therefore, effectively addressing the opioid crisis and these health outcomes will require combatting the stigma processes identified here and denser, more ensconced structural issues in rural communities, chiefly information diffusion, purposeful social isolation, and healthcare access and quality.

There are some limitations to this analysis. First, most participants, like the counties surveyed, were White, and thus, this study may not necessarily reflect perceptions, attitudes and behaviors of communities with greater racial/ethnic diversity. Secondly, the counties being assessed had predominantly lower income populations and as a result the pronounced role of economics in forming perspectives found in this study may not be reflective of dynamics in more economically diverse areas.

In conclusion, juxtaposing commentary from professional stakeholders and PWUD, we found that PWUD in rural areas may experience considerable internalized stigma and stigma from professionals as well as the broader public. An intricate spectrum of psychosocial factors contribute to these stigmatizing attitudes, forces amassing in the context of limited information flow and region-wide socioeconomic marginalization. In turn, the work points to the potential utility of interventions—in particular those aimed at first responders and healthcare professionals—which emphasize the holistic traits of PWUD and deliver coordinated arguments on the moral and economic benefits of harm reduction and treatment.

Research Highlights:

Antagonism for treatment and prevention arises from perceived taxpayer cost burden

Stakeholders often contest the character and agency of PWUD

Stakeholders commonly use potentially stigmatizing terms on drug use/user milieu

Perceived class traits—e.g., appearance/behavior—may activate negative PWUD views

Rural public viewed as unaware of/unsympathetic to PWUD general challenges

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bogdan R, & Taylor SJ (1989). Relationships with severely disabled people: The social construction of humanness. Social Problems, 36(2), 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bolinski R, Ellis K, Zahnd WE, Walters S, McLuckie C, Schneider J, Rodriguez C, Ezell J, Friedman SR, & Pho M (2019). Social norms associated with nonmedical opioid use in rural communities: a systematic review. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 9(6), 1224–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA (2015). Stigma towards marijuana users and heroin users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 47(3), 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Arruda N, Zang G, Jutras-Aswad D, & Roy É (2019). The evolving drug epidemic of prescription opioid injection and its association with HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Montreal, Canada. Addiction, 114(2), 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JA (2010). Avoiding traps in member checking. The Qualitative Report, 15(5), 1102–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SM (2019). Respecting and empowering vulnerable populations: contemporary terminology. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15(3), 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K, & Belgrave LL (2007). Grounded theory. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Kuwabara SA, & O’Shaughnessy J (2009). The public stigma of mental illness and drug addiction: Findings from a stratified random sample. Journal of Social Work, 9(2), 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, & Nieweglowski K (2018). Stigma and the public health agenda for the opioid crisis in America. International Journal of Drug Policy, 59, 44–49. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Does M, Kline-Simon A, Charvat Aguilar N, Marino C, & Campbell C (2017). Stakeholder Engagement in a Patient-Activation Behavioral Intervention for Prescription Opioid Patients (ACTIVATE). Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews, 4(3), 194. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski K, Crawford D, Khan B, & Tyler K (2016). Current rural drug use in the US Midwest. Journal of Drug Abuse, 2(3). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezell JM, Choi C-WJ, Wall MM, & Link BG (2018). Measuring recurring stigma in the lives of individuals with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(1), 27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadanelli M, Cloud DH, Ibragimov U, Ballard AM, Prood N, Young AM, & Cooper HLF (2019). People, places, and stigma: a qualitative study exploring the overdose risk environment in rural Kentucky. International Journal of Drug Policy, 102588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, & Moore D (2011). The drug effect: Health, crime and society. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Rossi D, Mateu-Gelabert P, Nikolopoulos GK, Schneider JA, Smyrnov P, & Stall RD (2017). Interpersonal Attacks on the Dignity of Members of HIV Key Populations: A Descriptive and Exploratory Study. AIDS and Behavior, 21(9), 2561–2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Rossi D, & Ralón G (2015). Dignity denial and social conflicts. Rethinking Marxism, 27(1), 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, & Vlahov D (2003). Contextual determinants of drug use risk behavior: a theoretic framework. Journal of Urban Health, 80(3), iii50–iii58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Bowman SE, Zaller ND, Ray M, Case P, & Heimer R (2013). Barriers to medical provider support for prescription naloxone as overdose antidote for lay responders. Substance Use and Misuse, 48(7), 558–567. 10.3109/10826084.2013.787099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Oser CB, Knudsen HK, Lofwall M, Stoops WW, Walsh SL, Leukefeld CG, & Kral AH (2011). Individual and network factors associated with non-fatal overdose among rural Appalachian drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(1–2), 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EC (1962). Good people and dirty work. Social Problems, 10(1), 3–11. Public Act 099–0480, (2015). http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/99/099-0480.htm [Google Scholar]

- Keane H (2003). Critiques of harm reduction, morality and the promise of human rights. International Journal of Drug Policy, 14(3), 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Keane H (2009). Foucault on methadone: Beyond biopower. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20(5), 450–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Saitz R, & Wakeman S (2016). Language, substance use disorders, and policy: the need to reach consensus on an “addiction-ary.” Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 34(1), 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Brady JE, Havens JR, & Galea S (2014). Understanding the rural-urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid use and abuse in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e52–e59. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Pulkki-Brannstrom A-M, & Skordis-Worrall J (2014). Comparing the cost effectiveness of harm reduction strategies: a case study of the Ukraine. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 12(1), 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolla G, & Strike C (2020). Medicalization under prohibition: the tactics and limits of medicalization in the spaces where people use illicit drugs. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Larson JE, & Corrigan PW (2010). Psychotherapy for self-stigma among rural clients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(5), 524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner AM, & Fauci AS (2019). Opioid Injection in Rural Areas of the United States: A Potential Obstacle to Ending the HIV Epidemic. Jama, 322(11), 1041–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gilmour S, Zhang H, Koyanagi A, & Shibuya K (2012). The epidemiological impact and cost-effectiveness of HIV testing, antiretroviral treatment and harm reduction programs. Aids, 26(16), 2069–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu-Gelabert P, Maslow C, Flom PL, Sandoval M, Bolyard M, & Friedman SR (2005). Keeping it together: stigma, response, and perception of risk in relationships between drug injectors and crack smokers, and other community residents. AIDS Care, 17(7), 802–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Priest KC, & Korthuis PT (2018). Treatment and Prevention of Opioid Use Disorder: Challenges and Opportunities. Ssrn, 0 10.1146/annurevpublhealth-040617-013526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Kennedy-Hendricks A, & Barry CL (2019). Stigma of Addiction in the Media In The Stigma of Addiction (pp. 201–214). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Moore D, & Fraser S (2006). Putting at risk what we know: Reflecting on the drug-using subject in harm reduction and its political implications. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3035–3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muncan B, Walters SM, Ezell J, & Ompad DC (2020). “They look at us like junkies”: influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs in New York City. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi JV Jr, Taylor R Jr, LeQuang JA, & Raffa RB (2018). What’s holding back abuse-deterrent opioid formulations? Considering 12 US stakeholders. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery, 15(6), 567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Lang A, & Olafsdottir S (2008). Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: A framework integrating normative influences on stigma (FINIS). Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 431–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Lucas JW, Ridgeway CL, & Taylor CJ (2014). Stigma, status, and population health. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LA, & Shaw A (2013). Substance use more stigmatized than smoking and obesity. Journal of Substance Use, 18(4), 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pike E, Tillson M, Webster JM, & Staton M (2019). A mixed-methods assessment of the impact of the opioid epidemic on first responder burnout. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Platt L, Sarang A, Vlasov A, Mikhailova L, & Monaghan G (2006). Street policing, injecting drug use and harm reduction in a Russian city: a qualitative study of police perspectives. Journal of Urban Health, 83(5), 911–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg KK, Monnat SM, & Chavez MN (2018). Opioid-related mortality in rural America: geographic heterogeneity and intervention strategies. International Journal of Drug Policy, 57, 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S (2018). A sociology of nothing: Understanding the unmarked. Sociology, 52(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shim JK (2010). Cultural Health Capital: A Theoretical Approach to Understanding Health Care Interactions and the Dynamics of Unequal Treatment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1), 1–15. 10.1177/0022146509361185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speltini G, & Passini S (2014). Cleanliness/dirtiness, purity/impurity as social and psychological issues. Culture & Psychology, 20(2), 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart H, Jameson JP, & Curtin L (2015). The relationship between stigma and self-reported willingness to use mental health services among rural and urban older adults. Psychological Services, 12(2), 141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmberg JP, & Martin CM (2016). Diagnosis–the limiting focus of taxonomy. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 22(1), 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N, van de Ven K, & Mulrooney KJD (2019). The impact of rurality on opioid-related harms: A systematic review of qualitative research. International Journal of Drug Policy, 102607 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans S, & Almeling R (2009). Objectification, standardization, and commodification in health care: a conceptual readjustment. Social Science & Medicine, 69(1), 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, Banik S, Turan B, Crockett KB, Pescosolido B, & Murray SM (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Neitzke-Spruill L, O’Connell D, Highberger J, Martin SS, Walker R, & Anderson TL (2018). Understanding Geographic and Neighborhood Variations in Overdose Death Rates. Journal of Community Health. 10.1007/s10900-018-0583-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, & Rich JD (2018). Barriers to medications for addiction treatment: How stigma kills. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(2), 330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead J, Shaver J, & Stephenson R (2016). Outness, stigma, and primary health care utilization among rural LGBT populations. PloS One, 11(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DP, Donald B, Shattock AJ, Wilson D, & Fraser-Hurt N (2015). The cost-effectiveness of harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, S5–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JD, Berk J, Matson P, Spicyn N, Alvanzo A, Adger H, & Feldman L (2018). A Cross-sectional Survey Using Clinical Vignettes to Examine Overdose Risk Assessment and Willingness to Prescribe Naloxone. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N (2020). Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2017–2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodak A, & Maher L (2010). The effectiveness of harm reduction in preventing HIV among injecting drug users. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin, 21(4), 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]