Abstract

Objective

Adolescent engagement in decision‐making processes in health care and research in the field of chronic respiratory diseases is rare but increasingly recognized as important. The aim of this study was to reflect on adolescents' motives and experiences in the process of establishing an advisory council for adolescents with a chronic respiratory disease.

Methods

A qualitative evaluation study was undertaken to assess the process of starting an advisory youth council in a tertiary hospital in the Netherlands. Data collection consisted of observations of council meetings, in‐depth interviews with youth council members, and moderated group discussions. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis to explore the experiences of the council members (n = 9, aged 12–18 years, all with a chronic respiratory disease). Two‐hour council meetings took place in the hospital to provide solicited and unsolicited advice to improve research and care.

Results

Three themes were identified as motives for adolescents to engage in an advisory council: (1) experience of fun and becoming empowered by their illness; (2) the value of peer support and contact; and (3) being able to contribute to care and research. The council's output consisted of solicited advice on information leaflets for patients, study procedures, and dietary menu options for hospitalized children. The council struggled to have their unsolicited advice heard within the hospital.

Conclusions

Council members experienced engagement as beneficial at the individual, group, and organizational levels. However, meaningful youth engagement requires connectedness with, and official support from, officials at all levels within an organization.

Keywords: adolescents, cystic fibrosis, patient involvement, pediatric asthma, shared decision making

1. INTRODUCTION

It may be challenging to treat adolescents with a chronic respiratory disease. 1 Due to complex biological and psychosocial changes, they think, feel, and act differently than younger children. Services are generally not adapted to this age group, while adolescent patients have specific needs. 2 , 3 At the same time these patients are making the transition from caregiver‐supervised pediatric patients to being young adult patients who need to self‐manage their disease and organize their own health visits. Learning from the experiences of adolescents themselves might help to improve care for this group. Although there is growing attention being paid to the participation of adolescents in decision‐making processes regarding treatment, service improvement, and scientific health and biomedical research, 4 , 5 , 6 it is still rare in clinical practice. In clinical research, funders increasingly encourage, and in the Netherlands even require, researchers to work actively with patients to advance research and clinical care. 7 , 8

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) has been one of the driving forces of child participation. 9 , 10 , 11 The UNCRC advocates that children and adolescents have a right to be heard and considered in any matters affecting them. National legislative frameworks further support children's rights to be actively involved in decision‐making processes that affect them. In the Netherlands, where this study was conducted, children at the age of 12 are considered to have a strong voice in decisions on care and health research (together with their parents), and from the age of 16, they have the right to consent or refuse treatment and/or research. With the emergence of new (burdensome) treatments for children with chronic respiratory diseases and the introduction of “transition” clinics and self‐management programs for adolescents with chronic respiratory diseases, 12 it is more important than ever to engage adolescents with such diseases in healthcare processes and research to address their needs.

In the field of respiratory conditions, a variety of organizations have been successful in involving (adult) patients in international scientific congresses, 13 task forces, research (priority) studies, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 and international consortia. 7 , 19 Despite the growing awareness of its value, the pediatric perspective is often overlooked and there is a lack of knowledge of how to engage children in a meaningful way at an organizational level. 20 Practice shows that youth engagement in hospital settings is not simple. 21 “Adulteration” (dominance of adult perspectives), tokenism (making only a symbolic effect to be inclusive), and pseudo‐participation have been observed as common pitfalls for professionals initiating child participation. There is a lack of studies on the collective experiences of pediatric patient engagement from the perspective of adolescents themselves, and seeking to fill this gap may provide more insights for healthcare providers and researchers on how to involve children in a meaningful way in research and care. We, therefore, aim to explore the experiences of adolescents with a chronic respiratory disease who were involved in a newly established advisory youth council in a tertiary hospital.

2. METHODS

2.1. Advisory youth council

The youth council started in June 2018 and was initiated by the Departments of Pediatric Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine at the Amsterdam University Medical Centers (Amsterdam UMC), a tertiary medical center in the Netherlands, in collaboration with the Department of Ethics, Law, and Humanities for the process evaluation.

The youth council comprised nine members, aged from 12 to 18 years (at the start of the council), five girls and four boys. All of them have (a) chronic respiratory diseases: eight have asthma (ranging from mild to severe) and one has cystic fibrosis (CF; Table 1). Council members were recruited through various channels (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of the youth council participants

| Council members | 9 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12–18 |

| Female/male | 5/4 |

| Educational level | Secondary school (n = 9) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Asthma | 8 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 |

Table 2.

Recruitment channels of the youth council members

| Channel of recruitment | |

|---|---|

| Pediatric pulmonologist | 5 |

| Health psychologist | 1 |

| Mother was a coworker | 1 |

| Mother who participated in the adult advisory board | 1 |

| Lung Foundation Netherlands | 1 |

Every 2–3 months the council members met for 2 h after school in the hospital. During these “pizza‐evenings,” pizzas, and healthy snacks were served and they discussed questions posed by researchers and physicians as well as their own ideas for how to improve care and research. The meeting was moderated by one or two researchers (E. S. and S. V.).

2.2. Council evaluation: Data collection and analysis

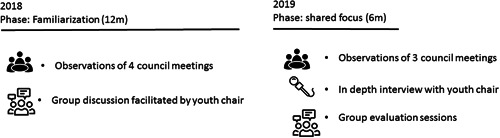

To assess the adolescents' subjective experiences, a qualitative approach was used. Qualitative methods are preferred for gaining an understanding of people's experiences and life‐world contexts. 22 The study comprised two phases (Figure 1). Data collection consisted of observations of council meetings, in‐depth interviews, and group discussions with the adolescents undertaken by an independent researcher (B. G.). In line with the explanatory aim, the observations were not based on a structured protocol, but were open. Topics of the interviews and group‐sessions included members' experiences in the youth council, their motivations (individual and group) and the outcomes (see an example in Table S1).

Figure 1.

Qualitative approaches used during the two phases of the study

The study took place over 22 months, from January 2018 to October 2019, and was conducted by an independent evaluation researcher (B. G.), using thematic analysis, a method for identifying and analyzing patterns in qualitative data. 23 Preliminary findings were discussed with two other independent researchers (C. D. and T. T.) to reach consensus on the identified themes. The process of data collection and analysis was iterative, as the process alternated during the study; the data were analyzed during the process. 24 In this way, the emerging themes could be further explored and validated in the following phase until data saturation was reached.

All patients and parents/caregivers gave their consent for participation. The MRB of the Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, regarded the study as not being subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Confidentiality was maintained using restricted, secure access to the data, destruction of audiotapes the following transcription, and anonymizing the transcripts.

3. RESULTS

The thematic analysis revealed three themes regarding the experience of the adolescents: (1) fun and enabling (in contrast with feeling a patient), (2) peer support and contact, and (3) contributing to care and research.

3.1. Fun and enabling (in contrast with feeling like a patient)

Having pizza together every 2–3 months, going on an annual trip to the national youth pediatric hospital council meeting representing the hospital, or attending research seminars with the facilitators, were perceived as “fun.” Fun is more than feeling happy; it is about laughing, feeling connected, experiencing different vibes, flow, and so on. Especially if the meetings were held during school hours and they were allowed to skip their lessons, they felt “important.” Plus, having a hoodie with a council logo they had designed made them proud. One council member commented: “There are also adolescents that do not participate… poor them, they don't know what they miss, traveling to Groningen [city where the national youth council meeting was held] and pizza every month.”

Moreover, the adolescents' experience was that the youth council provided them a chance to help their peers in the same situation by speaking on their behalf about improvements in child‐ and youth‐friendly hospitals and research. They experienced the powerful feeling that they could contribute to a bigger whole, especially to the position of children with respiratory disease. Through the youth council, the members could contribute in a positive way because of their illness, when most of the time their illness was considered to be disabling. A council member mentioned in an interview: “It is a good format [chatting and advice], since you are not solely thinking ‘oh we are so sad', you are doing something good with it.”

3.2. Peer support and peer contact

For youth council members, one of the most important values of participation was personal support, and the opportunity to chat with peers in an arranged but informal setting. At the start of each session, the members had a pizza together and talked informally about their experiences of illness. This moment of relaxed conversation meant a lot to most of the council members. They feel that they understand each other easily, and exchange tips and tricks about dealing with their illness, for example, how to deal with the heat in the summer, or how to improve compliance. This is perceived as a unique situation because in daily life the council members sometimes feel different from their peers.

A: “Someone who really understands.”

B: “You can tell your other friends, but they won't understand. You feel supported, since you are not the only one.”

C: “Normally we are always the only one.”

The members have a WhatsApp group in which they keep in touch, and some of them also see each other outside the group meetings, for example, for a support visit if one member is admitted to the hospital. This support gives them strength and confidence: “I feel so much more confident since I started this council. It really helped me. I would recommend this [engagement in the council] to other adolescents too.”

3.3. Contributing to care and research

In the first year, getting to know each other and peer support proved most important for the participants. Slowly, and with help of the facilitator's encouragement, the council started to discuss topics that were considered important for the hospital. Care professionals and researchers from the hospital also found the council was most useful for offering advice, for example, they provided advice on the design of pediatric patient information leaflets and consent forms, on the attractiveness of a flyer to attract adolescents to take part in a study, on the attractiveness of a social media account to inform the public about a randomized controlled trial, on the burden of measurements for a proposed pediatric study and on new menus and dietary options for the pediatric hospital (see Figure S1A–D for examples of the output). Besides, they assisted researchers in presenting a scientific poster on the youth council during a national respiratory conference. In the adolescents' experience, in general, adults often use complicated words and wanted to push them into a predetermined direction, based on assumptions of what was best for the adolescents. Although the adolescents felt that the facilitators gave them room for their own input, they felt the power for change was still in the hands of adults. In the words of a council member:

“… very often they [adults in general] try to send you in a direction, but I have my own opinion… like: I think this and it is not that… they should give you an opportunity to say it… often they interrupt me… I am the one with the problem, they need to help me and not draw a conclusion before I have said something.”

After a year, the members started to become impatient. They felt that they could contribute more and were inspired by stories of other councils in annual national meetings of Dutch youth (hospital) councils. They felt eager to provide unsolicited advice on care, for example, making hospital rooms more child‐ and adolescent‐friendly. However, they experienced dependence on hospital health professionals and management. The council was initiated by researchers on respiratory illness and was not formally established as a client council by the hospital management. Consequently, the council had no official “rights” or “position” within the hospital, where there was limited awareness of its existence. In addition, the facilitator(s) were not in a position to make decisions on all the topics that the council members put on their own agenda: “We bring ideas, but then nothing happens. Many people 'like' us, but they don't really do something with it. They do not know how to collaborate with us.” Nevertheless, they did make some small steps. They were even awarded a prize for their initiative by the Dutch Lung Foundation (Professor Peter Sterk participation prize 2019). The council members were eager to continue their engagement and plans. In 2020, the Dutch Child and Hospital Foundation (Stichting Kind & Ziekenhuis) in collaboration with the Dutch Pediatric Society and the Missing Chapter Foundation will start a project to support the embedding of youth councils in Dutch hospitals. Our youth council aims to collaborate in this project to build on the strong base and achieve a sustainable role of the council.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our study provided unique insights into the views of adolescents with chronic respiratory diseases in pediatric patient engagement in a hospital setting. It shows that adolescents participating in a youth council, value group engagement, and experience different benefits, from having fun to peer support and feeling more confident. However, our study also shows that long‐term and meaningful participation requires an organizational shift that moves from an adult‐led agenda towards a youth‐led agenda. There is a need for an organizational climate in which unsolicited advice is valued and facilitated by formal structures to prevent adolescent patients' frustration and demotivation in the longer term. It is, however, interesting to see how important the meetings are for enabling adolescents not to feel alone, feel supported, have fun, and feel important. In that sense, the meetings have been most successful. One could also imagine that in the coming years the council will be more productive since they have built a strong basis with each other.

Previous studies on patient engagement have also shown that this may have an empowering effect on participants 7 , 25 ; it enables them to develop self‐esteem and positive self‐regard, enhances communication skills, and to become active health consumers. In the field of pediatric respiratory medicine, for example, it has been found that a more participatory decision‐making style on the part of the health professionals for asthma patients' visits was associated with greater patient satisfaction. 26

Our study also shows that although peer support was considered important, working towards a common goal and “helping others” were also perceived as essential. The youth council was considered to be more than just a peer‐support intervention. The aim was to make structural improvements in the hospital to make a positive impact on disease outcomes or disease‐related quality of life. 27 How to transform an organization into one that embraces the engagement of adolescent patients is still unclear. There are different frameworks for public engagement, all of which warn about the dangers of tokenism and tick‐box approaches to engagement, and focus on leadership within systems. 28

Although this a unique study on the experiences of adolescent participation in a tertiary hospital, some limitations should be noted. The council members represent only a small subset of the total patient population with chronic respiratory disease in our hospital, although we did try to include adolescents with diverse backgrounds, ages, and disease severity. There was only one CF patient in our council, due to the segregation policy for CF patients in our hospital. Nevertheless, the recent lockdown periods due to the COVID‐19 pandemic made us aware of the possibilities for participation using online meetings, so this would offer possibilities to include more CF patients in the council. In addition, the participatory research approach involved a learning process for adolescents as well as the facilitators. The involvement of other relevant stakeholders in this study could have been a strength and a facilitator could potentially become co‐owner of the engagement of adolescents in the hospital.

An important lesson for clinicians who aim for meaningful adolescent engagement, for example, when implementing transition practices, 1 is that it is essential that voices are not only heard but also acted upon. It should lead to actual changes in policy and practice, such as adapting a management or study protocol or making changes to patient information leaflets. Practice showed that this is not easy and requires a commitment to be embedded within the organization. Similar to our findings, an evaluation of a UK hospital youth council also showed that not being taken seriously as an important barrier to successful pediatric patient engagement. 29 The UK council members valued feedback and evaluation of their ideas to ensure that their investment of time and energy led to actual improvements in the hospital.

Continuous reflection, collaboration with participation experts, and taking into account previously identified lessons for meaningful patient engagement from the patient perspective 7 , 30 , 31 could help researchers and physicians to set up long‐term successful pediatric engagement. This should include adapting information to the target audience and training physicians, researchers, management, and policymakers on adolescent patient engagement.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Barbara Groot and Susanne Vijverberg are responsible for the conception and design of the study. Susanne Vijverberg, Barbara Groot, and Niels Rutjes obtained funding for the study. Elise Slob, Susanne Vijverberg, Niels Rutjes, and Henriette Maitland set‐up the youth council. Elise Slob and Susanne Vijverberg moderated the youth council meetings, while Henriette Maitland chaired the youth council meetings. Data were collected by Barbara Groot. Data were analyzed and/or interpreted by Barbara Groot, Christine Dedding, and Truus Teunissen. Barbara Groot and Susanne Vijverberg drafted the manuscript. All coauthors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the version of the manuscript to be published.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the youth council members; Ahmet, Alysia, Elham, Emmanuel, Helianne, Jonathan, Lennart, and Veere for their valuable contribution. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge Ivo van den Bongaardt, Maud Butter, Erin Smeijsters, and Nienke Sikkens for their help with the organization of the council meetings, and the pediatric pulmonologists and health psychologists from the Emma Children's Hospital, as well as Sandra de Graaf (Lung Foundation Netherlands) for their help with recruitment of the council members.

Groot B, Dedding C, Slob E, et al. Adolescents' experiences with patient engagement in respiratory medicine. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2021;56:211–216. 10.1002/ppul.25150

REFERENCES

- 1. Roberts G, Vazquez‐Ortiz M, Khaleva E, et al. The need for improved transition and services for adolescent and young adult patients with allergy and asthma in all settings. Allergy. 2020. 10.1111/all.14427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vazquez‐Ortiz M, Angier E, Blumchen K, et al. Understanding the challenges faced by adolescents and young adults with allergic conditions: a systematic review. Allergy. 2020;75:1850‐1880. 10.1111/all.14258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roberts G, Vazquez‐Ortiz M, Knibb R, et al. EAACI Guideline on the effective transition of adolescents and young adults with allergy and asthma. Allergy. 2020. 10.1111/all.14459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron‐Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Q Health Care. 2011;24(1):28‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vat LE, Finlay T, Jan Schuitmaker‐Warnaar T, et al. Evaluating the "return on patient engagement initiatives" in medicines research and development: a literature review. Health Expect. 2020;23(1):5‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Schelven F, Boeije H, Mariën V, Rademakers J. Patient and public involvement of young people with a chronic condition in projects in health and social care: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2020;23:789‐801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Supple D, Roberts A, Hudson V, et al. From tokenism to meaningful engagement: best practices in patient involvement in an EU project. Res Involv Engagem. 2015;1(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Teunissen GJ, Visse MA, Laan D, de Boer WI, Rutgers M, Abma TA. Patient involvement in lung foundation research: A seven year longitudinal case study. Health. 2013;5(2):320‐330. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weil LG, Lemer C, Webb E, Hargreaves DS. The voices of children and young people in health: where are we now? Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(10):915‐917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UN Commission on Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of the Child, E/CN.4/RES/1990/74; 1990. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f03d30.html. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 11. Schalkers I, Dedding CWM, Bunders JFG. ‘[I would like] a place to be alone, other than the toilet'—Children's perspectives on paediatric hospital care in the Netherlands. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2066‐2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD009794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smyth D, Powell P, Masefield S. “Patients included” in the European Respiratory Society International Congress. Breathe. 2015;11(4):249‐254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rowbotham NJ, Smith S, Leighton PA, et al. The top 10 research priorities in cystic fibrosis developed by a partnership between people with CF and healthcare providers. Thorax. 2018;73(4):388‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hollin IL, Donaldson SH, Roman C, et al. Beyond the expected: identifying broad research priorities of researchers and the cystic fibrosis community. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(3):375‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noordhoek JJ, Gulmans VAM, Heijerman HGM, van der Ent CK. Aligning patients' needs and research priorities towards a comprehensive CF research program. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(3):382‐384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buzzetti R, Galici V, Cirilli N, et al. Defining research priorities in cystic fibrosis. Can existing knowledge and training in biomedical research affect the choice? J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(3):378‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW, Teerling J, Bunders JFG. Patients' priorities concerning health research: the case of asthma and COPD research in the Netherlands. Health Expect. 2005;8(3):253‐263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Bragt JJMH, Adcock IM, Bel EHD, et al. Characteristics and treatment regimens across ERS SHARP severe asthma registries. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1):1901163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gurung G, Richardson A, Wyeth E, Edmonds L, Derrett S. Child/youth, family and public engagement in paediatric services in high‐income countries: a systematic scoping review. Health Expect. 2020;23(2):261‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schalkers I, Parsons CS, Bunders JF, Dedding C. Health professionals' perspectives on children's and young people's participation in health care: a qualitative multihospital study. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(7‐8):1035‐1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braun V, Clarke V. What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐being. 2014;9:26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 4th ed Sage Publication Ltd; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanghoj S, Pappot H, Hjalgrim LL, Hjerming M, Visler CL, Boisen KA. Impact of service user involvement from the perspective of adolescents and young adults with cancer experience. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019;8(5):534‐539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Coyne I, et al. Provider use of a participatory decision‐making style with youth and caregivers and satisfaction with pediatric asthma visits. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2018;9:147‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kew KM, Carr R, Crossingham I. Lay‐led and peer support interventions for adolescents with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD012331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co‐design pilot. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):785‐801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coad J, Flay J, Aspinall M, Bilverstone B, Coxhead E, Hones B. Evaluating the impact of involving young people in developing children's services in an acute hospital trust. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(23):3115‐3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Wit M, Teunissen T, van Houtum L, Weide M. Development of a standard form for assessing research grant applications from the perspective of patients. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gibbs L, Marinkovic K, Black AL, et al. Kids in action: participatory health research with children In: Wright MT, Kongats K, eds. Participatory Health Research: Voices from Around the World. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018:93‐113. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.