Abstract

Objective

Cardiovascular complications are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). The acquired kinase mutation JAK2V617F plays a central role in these disorders. Mechanisms responsible for cardiovascular dysfunction in MPNs are not fully understood, limiting the effectiveness of current treatment. Vascular endothelial cells (ECs) carrying the JAK2V617F mutation can be detected in patients with MPNs. The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that the JAK2V617F mutation alters endothelial function to promote cardiovascular complications in patients with MPNs.

Approach and Results

We employed murine models of MPN in which the JAK2V617F mutation is expressed in specific cell lineages. When JAK2V617F is expressed in both blood cells and vascular ECs, the mice developed MPN and spontaneous, age‐related dilated cardiomyopathy with an increased risk of sudden death as well as a prothrombotic and vasculopathy phenotype on histology evaluation. In contrast, despite having significantly higher leukocyte and platelet counts than controls, mice with JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells alone did not demonstrate any cardiac dysfunction, suggesting that JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs are required for this cardiovascular disease phenotype. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the JAK2V617F mutation promotes a pro‐adhesive, pro‐inflammatory, and vasculopathy EC phenotype, and mutant ECs respond to flow shear differently than wild‐type ECs.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the JAK2V617F mutation can alter vascular endothelial function to promote cardiovascular complications in MPNs. Therefore, targeting the MPN vasculature represents a promising new therapeutic strategy for patients with MPNs.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, endothelial cells, myeloproliferative disorders, thrombosis, vascular diseases

Essentials.

A JAK2V617F‐positive murine model of MPN develops spontaneous heart failure with a prothrombotic, vasculopathy, and cardiomyopathy phenotype.

Histology evaluation revealed a prothrombotic, vasculopathy, and cardiomyopathy phenotype.

JAK2V617F‐mutant endothelial cells (ECs) are required to develop this cardiovascular disease phenotype.

JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs display a pro‐adhesive and pro‐inflammatory phenotype.

1. INTRODUCTION

The chronic Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal stem cell disorders characterized by hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) expansion and overproduction of mature blood cells. Patients with MPNs suffer from many debilitating complications including both venous and arterial thrombosis, with cardiovascular events being the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. 1 The acquired kinase mutation JAK2V617F plays a central role in these disorders and can be detected in approximately 75% of all patients with an MPN. 2 Mechanisms responsible for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in MPNs remain incomplete, limiting the effectiveness of current treatment.

Recently, several studies have reported that JAK2V617F is one of the common mutations associated with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), which is present in 10% to 20% of people older than 70 years. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Individuals with CHIP progress to malignancy at a rate of ~0.5% per year. 8 , 9 Unexpectedly, CHIP carriers have a two‐ to four‐fold increase in CVDs with worsened clinical outcomes, which rivals or may even exceed those traditional CVD risk factors. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 In particular, individuals with JAK2V617F‐mutant CHIP have 12 times the risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke compared to individuals without any CHIP‐associated mutation. 5 , 7 Therefore, because up to 40% of patients with MPNs develop thrombosis, 1 and MPN‐associated mutation in seemingly healthy individuals is associated with an excess of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, MPN provides an ideal model system to investigate the relationship between hematopoietic mutations and cardiovascular disorders.

Vascular endothelial cells (ECs) play critical roles in the regulation of hemostasis and thrombosis. 10 ECs carrying the JAK2V617F mutation can be detected in isolated (by laser microdissection) liver or spleen ECs in many patients with MPNs. 11 , 12 One study demonstrated that both wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant spleen ECs co‐exist in the same patients and mutant ECs comprise 40% to 100% of all splenic ECs. 12 The mutation can also be detected in 60% to 80% of EC progenitors derived from the hematopoietic lineage and, in some reports based on in vitro culture assays, in endothelial colony‐forming cells from MPN patients. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Previously, to study the effects of the JAK2V617F‐bearing vascular microenvironment on MPN stem cell function, we crossed mice that bear a Cre‐inducible human JAK2V617F gene (FF1) 17 with Tie2‐Cre mice 18 to express JAK2V617F specifically in all hematopoietic cells (including HSPCs) and ECs (Tie2±FF1± or Tie2FF1), 19 so as to model the human diseases in which both the hematopoietic stem cells and ECs harbor the mutation. As we have reported, Tie2FF1 mice develop a myeloproliferative phenotype with leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, significant splenomegaly, and greatly increased numbers of hematopoietic stem cells by 8 weeks of age. 19 , 20 , 21 In this work, we tested the hypothesis that the JAK2V617F mutation alters endothelial function to promote cardiovascular complications in patients with MPNs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Experimental mice

JAK2V617F Flip‐Flop (FF1) mice 17 were provided by Radek Skoda (University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland) and Tie2‐Cre mice 18 by Mark Ginsberg (University of California, San Diego). FF1 mice were crossed with Tie2‐Cre mice to express JAK2V617F specifically in hematopoietic cells and ECs (Tie2±FF1± or Tie2FF1 mice). All mice used were crossed onto a C57BL/6 background and bred in a pathogen‐free mouse facility at Stony Brook University. CD45.1+ congenic mice (SJL) were purchased from Taconic Inc (Albany, NY). All mice were fed a standard chow diet. No randomization or blinding was used to allocate experimental groups. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on mildly anesthetized spontaneously breathing mice (sedated by inhalation of 1% isoflurane, 1 L/min oxygen), using a Vevo 3100 high‐resolution imaging system (VisualSonics Inc, Toronto, Canada). Both parasternal long‐axis and sequential parasternal short‐axis views were obtained to assess global and regional wall motion. Left ventricular (LV) dimensions at end‐systole and end‐diastole and fractional shortening (percent change in LV diameter normalized to end‐diastole) were measured from the parasternal long‐axis view using linear measurements of the LV at the level of the mitral leaflet tips during diastole. LV ejection fraction (EF), LV fractional shortening (FS), and LV mass are measured by using standard formulas for the evaluation of LV systolic function. 22

2.3. Histology

Hearts and lungs were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C while shaking. The tissues were then washed multiple times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature to remove paraformaldehyde. Paraffin sections (5‐μm thickness) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E), reticulin, and Masson's trichrome using reagents and kits from Sigma (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) following standard protocols. Images were taken using an Olympus IX70 microscope or Nikon eclipse 90i microscope.

Diagnosis of microvasculopathy was done by light microscopy. In microvessels (diameter 10–20 μm), both the endothelial layer and the wall (medial) layer were identified. The endothelial layer was defined as the monocell layer at the inner part of the blood vessel wall. Endothelial cells were graded as thickened if the diameter of the cell layer was at least as thick as the endothelial cell cores. The wall layer (media) was defined as the polycell layer adjacent to the endothelium. Stenotic wall thickening was classified if the ratio of luminal radius to wall thickness was < 1. 23

2.4. Stem cell transplantation assays

Six‐ to eight‐week‐old wild‐type (CD45.1) recipient mice were irradiated with two doses of 540 rad 3 hours apart and then received 1 × 106 unfractionated marrow cells from Tie2FF1 or Tie2‐Cre control (CD45.2) donor mice by standard intravenous tail vein injection using a 27G insulin syringe. Peripheral blood was obtained every 4 weeks after transplantation and CD45.2 percentage chimerism and complete blood counts were measured.

2.5. Complete blood counts

Peripheral blood was obtained from the facial vein via submandibular bleeding, collected in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube, and analyzed using a Hemavet 950FS (Drew Scientific).

2.6. Isolation and culture of murine lung and cardiac ECs

Primary murine lung and cardiac EC (CD45−CD31+) isolation was performed as we previously described. 20 , 24 , 25 Briefly, mice were euthanized and the chest was immediately opened through a midline sternotomy. The left ventricle was identified, and the ventricular cavity was entered through the apex with a 27‐gauge needle. The right atrium was identified and an incision was made in the free wall to exsanguinate the animal and to allow the excess perfusate to exit the vascular space. The animal was perfused with 30 mL of cold PBS. The heart and lung tissue were collected and minced finely with scissors. The tissue fragments were digested in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing 1 mg/mL collagenase D (Roche, Switzerland), 1 mg/mL collagenase/dispase (Roche), and 25 U/mL DNase (Sigma) at 37°C for 2 hours with shaking, after which the suspension was homogenized by triturating. The homogenate was filtered through a 70 μm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and pelleted by centrifugation (400 g for 5 minutes). Cells were first depleted for CD45+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) and then positively selected for CD31+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec) using magnetically labeled microbeads according to the manufacturer's protocol. Isolated ECs (CD45−CD31+) were cultured on 1% gelatin‐coated plates in complete EC medium as we previously described, 24 with no medium change for the first 72 hours to allow EC attachment followed by medium change every 2 to 3 days. Cells were re‐selected for CD31+ cells when they reached >70% to 80% confluence (usually after 3–4 days of culture).

2.7. Shear stress application

Primary murine lung ECs (passage 3‐6) were seeded on 1% gelatin‐coated 6‐well culture plates and allowed to grow to confluence. Unidirectional pulsatile shear stress at 60 dyne/cm2 was applied to confluent EC monolayers at 37°C for 1 hour, using a programmable cone and plate shearing device. 26 , 27 The 60 dyne/cm2 shear stress was selected not only because it mimics the hemodynamic stress condition of mouse aortic arch blood flow, 28 but also because it is compatible with our in vitro cell culture. Following shear exposure, EC monolayer was washed with PBS and collected for further testing.

2.8. Assays to examine endothelial cell in vitro angiogenesis

EC tube formation assay was performed as a measure of angiogenesis in vitro. Matrigel® matrix (10 mg/mL, Corning Inc, Corning, NY) were thawed overnight at 4°C and kept on ice until use; 150 μL Matrigel per well was added to pre‐chilled 48‐well culture plate. After gelation at 37°C for 30 minutes, gels were overlaid with 8 × 104 primary murine cardiac ECs (passage 3‐4) in 300ul of complete EC medium with serum‐free expansion medium, or Pf4/FF1 modified Kenney’s freezing medium (MKCM), or control MKCM (all at 1:1 volume ratio). Tube formation was inspected after a period of 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours and images were captured with a phase‐contrast microscope (AMEX‐1200, AMG, Bothell, WA). The quantification of the capillary tube formation was performed using the ImageJ® software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) by counting the number of nodes (branch points), tubes, and loops in four non‐overlapping areas at 10× magnification.

2.9. Flow cytometry analyses of blood and tissue samples

Expression of EC cell adhesion molecules PECAM (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule, or CD31) and E‐selectin was measured by flow cytometry using anti‐mouse PECAM (Clone 390, BD Biosciences) and anti‐mouse E‐selectin (Clone 10E9.6, BD Biosciences) antibodies and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) cytometer. For measurement of circulating monocytes, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were incubated with a cocktail of antibodies against granulocytes (Ly‐6G–FITC, 1A8, Biolegend), myeloid cells (CD11b‐PE, M1/70, Biolegend) and monocyte subsets (Ly‐6C–APC, HK1.4, Biolegend). Ly‐6Chigh monocytes were identified as CD11bhiLy‐6GloLy‐6Chi cells.

2.10. Gene expression analysis by real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used for real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to verify differential expression of Kruppel‐like factors 2 and 4, thrombomodulin, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), interleukin‐1β, interleukin‐6, and epidermal growth factor‐like domain 7 on an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Values obtained were normalized to the endogenous Actin beta (Actb) gene expression and relative fold changes compared to control samples was calculated by the 2ΔΔCT method. All assays were performed in triplicate.

2.11. Transcriptome analysis of cardiac ECs using RNA sequencing

Cardiac ECs (CD45−CD31+) were isolated from Tie2FF1 or Tie2‐Cre control mice by tissue digestion and magnetic bead isolation as described above. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA integrity and quantitation were assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For each sample, 400 ng of RNA was used to generate sequencing libraries using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) following manufacturer's recommendations. The clustering of the index‐coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using PE Cluster Kit cBot‐HS (Illumina) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina platform. Index of the reference genome was built using hisat2 2.1.0 and paired‐end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using HISAT2. HTSeq v0.6.1 was used to count the reads numbers mapped to each gene. Differential expression analysis between wild‐type control ECs (from Tie2‐Cre mice, n = 3) and JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs (from Tie2FF1 mice, n = 3) was performed using the DESeq R package (1.18.0). The resulting P‐values were adjusted using Benjamini and Hochberg's approach for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with an adjusted P‐value < .05 found by DESeq were assigned as differentially expressed. Gene Ontology (GO) (http://www.geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes was implemented by the ClusterProfiler R package. GO terms and KEGG pathways with corrected P‐value less than .05 were considered significantly enriched.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated using the Student t test or Mann‐Whitney test to compare differences between two groups. GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Development of spontaneous heart failure with increased risk of sudden death in the JAK2V617F‐positive Tie2FF1 mice

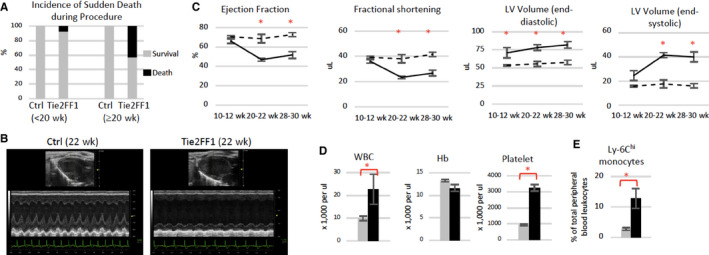

We noticed that there was an increased incidence of sudden death during performance of minor procedures (eg, submandibular bleeding) in Tie2FF1 mice, especially after 20 weeks of age (Figure 1A). This observation prompted us to examine the cardiac function of these mice using transthoracic echocardiography. At 20 weeks of age, Tie2FF1 mice displayed a phenotype of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with significant decreases in LV EF (47% versus 69%, P = .029) and FS (23% versus 38%, P = .029), and increases in LV end‐diastolic volume (78 μL versus 56 μL, P = .029) and end‐systolic volume (41 μL versus 18 μL, P = .029) compared to age‐matched Tie2‐Cre controls. There was no echocardiographic evidence for regional wall motion abnormalities including segmental akinesis, dyskinesis, thinned or scarred wall, suggesting there was no evidence of transmural myocardial infarction. The cardiac dysfunction in Tie2FF1 mice persisted at 30 weeks of age (Figure 1B and C). Because JAK2 is important for normal heart function, 29 , 30 we examined the mice at a younger age to be certain that the cardiovascular dysfunction we observed in Tie2FF1 mice was not due to developmental abnormalities. No significant differences (except a trend of increased LV end‐diastolic volume) in echocardiographic parameters were observed between Tie2FF1 and control mice at 10 weeks of age, suggesting that the DCM we observed in Tie2FF1 mice was likely not due to developmental abnormalities (Figure 1C). In addition, the cardiomyopathy was not due to anemia (which is a cause of high output heart failure), as there were no significant differences in red blood cell count, hemoglobin, or hematocrit level 19 (Figure 1D). The inflammatory Ly‐6Chigh monocytes, which are important participants at various stages of CVD progression and complication, 31 , 32 , 33 were significantly increased in peripheral blood of Tie2FF1 mice compared to controls (Figure 1E).

FIGURE 1.

Development of spontaneous congestive heart failure in Tie2FF1 mice. A, Increased incidence of sudden death in Tie2FF1 mice after 20 weeks of age (n = 14 in each group). B and C, Representative left ventricular echocardiographic tracings (B) and measurement of ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and left ventricular (LV) volume in Tie2 ctrl (dotted line) and Tie2FF1 (black line) mice (C). Results are expressed as mean value ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann‐Whitney test (n = 4 mice in each group at 10–12 weeks and 20–22 weeks, n = 10 mice in each group at 28–30 weeks). D, Blood counts of 20‐ to 22‐week‐old Tie2‐cre control (gray) and Tie2FF1 (black) mice (n = 5–6 in each group). E, Ly‐6Chi (CD11bhiLy‐6GloLy‐6Chi) monocytes in 20‐ to 30‐week‐old Tie2‐cre control (gray) and Tie2FF (black) mice (n = 4 in each group). Statistical significance for (D) and (E) was determined by the Mann‐Whitney test. *P < .05

3.2. JAK2V617F‐positive Tie2FF1 mice have a prothrombotic and vasculopathy phenotype

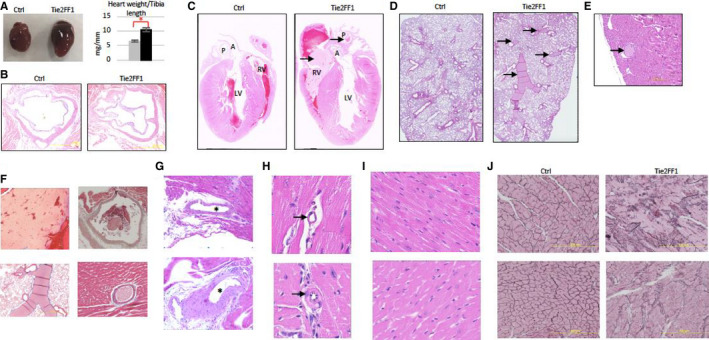

Pathological evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of DCM with significantly increased heart size and heart weight‐to‐tibia length ratio in Tie2/FF1 mice compared to controls (P = .0286; Figure 2A). However, no significant atherosclerotic lesions (Figure 2B) or myocardium infarctions were detected in Tie2FF1 mice, which are consistent with echocardiographic findings.

FIGURE 2.

The JAK2V617F‐positive Tie2FF1 mice have a prothrombotic and vasculopathy phenotype. A, Representative image of heart (left) and heart weight adjusted by tibia length (right) of 20‐ to 30‐week‐old Tie2 ctrl (gray) and Tie2FF1 (black) mice (n = 4–5 in each group). Statistical significance was determined by the Mann‐Whitney test. B, Representative hematoxylin/eosin (H&E)‐stained aortic root area of Tie2‐Cre ctrl and Tie2FF1 mice (magnification 4×). No significant atherosclerotic lesion was detected. C, Representative H&E staining of longitudinal sections of Tie2‐cre control and Tie2FF1 mice. Note the presence of thrombus (arrow) in right ventricle and main pulmonary artery of the Tie2FF1 mice. LV: left ventricle; RV: right ventricle; A: aortic root; P: main pulmonary artery (magnification 10×). D, Representative H&E staining of lung sections from Tie2‐cre control and Tie2FF1 mice. Note the presence of thrombus (arrow) in segment pulmonary arteries of the Tie2FF1 mice (magnification 10×). E, Representative H&E staining of coronary arteriole thrombus from the Tie2FF1 mice (magnification 10×). F, Representative Masson's trichrome staining demonstrates typical fibrin clot in right ventricle (upper left, 4×), pulmonary artery (upper right, 4×), segment pulmonary arteries (bottom left, 4×), and coronary arteriole (bottom right, 40×) of Tie2FF1 mice. G, Representative H&E staining of epicardial coronary arteries (stars) in Tie2‐cre control (top) and Tie2FF1 (bottom) mice. Note significant vascular wall thickening of the epicardial coronary artery in Tie2FF1 mice (magnification 4×). H, Representative H&E staining of intramyocardial coronary arterioles (arrow) in Tie2‐cre control (top) and Tie2FF1 (bottom) mice. Note stenotic lumen narrowing of the arteriole in Tie2FF1 mice (magnification 40×). I, Representative H&E‐stained cardiac sections taken from similar locations of the heart showing enlarged cardiomyocytes in Tie2FF1 mice (bottom) compared to control mice (top) (magnification 40×). J, Representative reticulin staining of cardiac sections taken from similar locations of the heart from control (left) and Tie2FF1 (right) mice are shown (magnification 20×). (For C–I: 5 control mice and 8 Tie2FF1 experiment mice were examined with similar findings; for J: n = 3 mice in each group were examined.) *P < .05

We conducted several studies to determine the cause(s) for the sudden death and DCM phenotypes we observed in Tie2FF1 mice. First, we determined whether the JAK2V617F‐positive Tie2FF1 mice developed spontaneous pulmonary thromboembolism, which is a common cause of sudden death. 34 We found thrombosis in the right ventricle and both main and segment pulmonary arteries in Tie2FF1 mice, while age‐matched Tie2‐cre control mice had no evidence of spontaneous thrombosis in the heart or lungs (Figure 2C, D, and F). In addition, although we did not observe thrombosis in the main (epicardial) coronary arteries, we found thrombosis in scattered coronary arterioles (microvessels) in some of the Tie2FF1 mice examined (Figure 2E and F). Such microvascular thrombosis in the coronary circulation can contribute to the development of dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. 35 , 36 Taken together, these results indicate that the JAK2V617F‐positive Tie2FF1 mice have a prothrombotic phenotype affecting both the arterial and venous circulations.

We next examined the coronary vasculature of both Tie2FF1 and age‐matched Tie2‐cre control mice by light microscopy. Compared to control mice, Tie2FF1 mice demonstrated significant vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and media wall thickening of their epicardial coronary arteries (Figure 2G). In addition, there was significant stenotic lumen narrowing (ie, ratio of luminal radius to wall thickness < 1) involving scattered intramyocardial coronary arterioles in Tie2FF1 mice (Figure 2H). These findings indicate that there is both macro‐ and micro‐vasculopathy in Tie2FF1 mice.

Microscopic examinations of heart sections under high magnification revealed enlarged cardiomyocytes and increased reticulin fibers in Tie2FF1 mice compared to control mice (Figure 2I–J), reflecting the cardiac remodeling effects of both microvascular thrombosis and vasculopathy we observed in these mice. Such pathological cardiac remodeling can further impair cardiac function of Tie2FF1 mice.

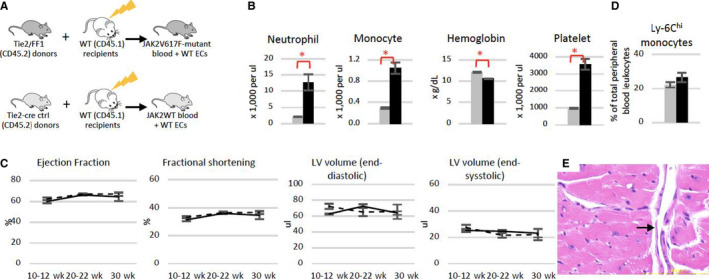

3.3. JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs are required to develop the cardiovascular complications in Tie2FF1 mice

In contrast to other murine models published to date in which cardiovascular diseases only develop when the mice are challenged with additional risk factors, 7 , 32 , 33 , 37 , 38 our Tie2FF1 mice, in which the JAK2V617F mutation is expressed in both blood cells and vascular ECs, develop spontaneous heart failure with increased risk of sudden death when fed a regular chow diet. This difference suggests that mutant ECs can accelerate the cardiovascular pathology in this JAK2V617F‐positive MPN murine model. To begin to address this hypothesis, we generated a chimeric murine model with JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells and wild‐type vascular ECs by transplanting Tie2FF1 marrow cells into wild‐type recipients. The transplantation of Tie2‐cre control marrow cells into wild‐type recipients served as a control (Figure 3A). Recipients of Tie2FF1 marrow developed significant neutrophilia, monocytosis, and thrombocytosis after transplantation (Figure 3B), a peripheral blood phenotype virtually identical to that of primary Tie2FF1 mice. We observed a small decrease in the hemoglobin levels in recipients of Tie2FF1 donor compared to controls, probably due to marrow transplantation‐induced stress hematopoiesis in this particular model. Importantly, echocardiographic evaluation did not reveal any differences in cardiac functional parameters between recipients of Tie2FF1 marrow and recipients of wild‐type marrow during 8‐month follow‐up after transplantation (Figure 3C). There was no difference in peripheral blood Ly‐6Chigh monocyte frequency between recipients of Tie2‐cre marrow and recipients of Tie2FF1 marrow (Figure 3D). Histology examination at the time of harvest did not reveal evidence of spontaneous thrombosis or coronary vasculopathy (Figure 3E). These results suggest that JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells alone are not sufficient to generate the spontaneous CVD phenotype we observed in Tie2FF1 mice; JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs are required.

FIGURE 3.

Normal heart function in mice with JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells and wild‐type vascular endothelial cells. A, Experimental scheme to generate a chimeric murine model with JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells and wild‐type vascular endothelium. B, Blood counts in recipient mice of either Tie2‐cre control (gray) or Tie2FF1 (black) marrow cells 22 weeks after transplantation (n = 5 mice in each group). C, Serial measurements of ejection fraction, fractional shortening, and left ventricular (LV) volumes in recipients of Tie2‐cre control marrow (dotted line) and recipients of Tie2FF1 marrow (black line; n = 5 mice in each group). D, Ly‐6Chi monocytes in recipient mice of Tie2‐Cre control (gray) or Tie2FF1 (black) marrow cells 22 weeks after transplantation (n = 5 mice in each group). E, Representative hematoxylin/eosin staining of intramyocardial coronary arterioles (arrow) in a recipient mouse of Tie2FF1 marrow (magnification 40×). Statistical significance for B–D was determined by the Mann‐Whitney test. *P < .05

3.4. JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs display a pro‐adhesive and pro‐inflammatory phenotype and respond to flow shear stress differently than wild‐type ECs

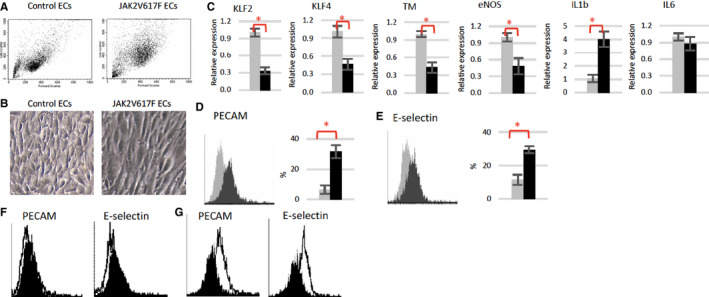

We studied how the JAK2V617F mutation alters endothelial function using primary murine cardiac ECs (CD45−CD31+) isolated from Tie2‐cre control and Tie2FF1 mice. 20 , 25 , 39 First, we examined EC morphology under static culture condition (ie, without flow shear stress). EC cell area correlates with cell stiffness and predicts cellular traction stress, which are involved in cell adhesion and migration. 40 , 41 Both microscopic examination and flow cytometric analysis revealed that JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs are larger than wild‐type ECs when seeded at similar cell density (Figure 4A and B).

FIGURE 4.

JAK2V617F‐mutant quantitative polymerase chain reaction (ECs) display a pro‐adhesive and pro‐inflammatory phenotype. A, Representative flow cytometry dot plots of wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs. Note JAK2V617F ECs have higher forward scatter (ie, increased cell size) and side scatter (ie, increased granularity) compared to wild‐type (WT) ECs. B, Representative bright field images of wild‐type and JAK2V617F ECs (magnification: 10×). C, Gene expression levels in wild‐type (gray) and JAK2V617F (black) murine ECs were measured using real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Gene expression in VF ECs is shown as the fold change compared to WT EC expression, which was set as “1.” D and E, Representative flow cytometry histogram plots and quantitative analysis of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM; D) and E‐selectin (E) expression in un‐sheared wild‐type (gray) and JAK2V617F‐mutant (black) ECs. F and G, Representative flow cytometry histogram plots of PECAM and E‐selectin expression in unsheared (black) vs sheared (white) wild‐type ECs (F) and JAK2V617F ECs (G). *P < .05

We examined the gene expression levels of several key EC function regulators. Kruppel‐like factors 2 (KLF2) and 4 (KLF4) are important regulators of vascular function and confer an anti‐atherogenic and anti‐thrombotic endothelial phenotype. 42 , 43 Both KLF2 (0.3‐fold, P = .007) and KLF4 (0.5‐fold, P = .014) mRNA levels were significantly reduced in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to wild‐type ECs. Thrombomodulin (TM) and eNOS are two downstream targets of KLF2/4 signaling. 43 Thrombomodulin is a vascular endothelial glycoprotein receptor that binds and neutralizes the prothrombotic actions of thrombin, and activates the natural anticoagulant protein C. 44 Disturbances of the thrombomodulin–protein C antithrombotic mechanism are the most important known etiology for clinical disorders of venous thrombosis. 45 eNOS plays an essential role in the regulation of endothelial function through the generation of nitric oxide, which inhibits platelet and leukocyte adhesion to the vessel wall and inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. 46 , 47 Decreased nitric oxide (NO) as a consequence of impairment in eNOS is a hallmark of many CVDs. 48 Consistent with the prothrombotic and vasculopathy phenotype we have observed in Tie2FF1 mice, both TM (0.4‐fold, P = .005) and eNOS (0.5‐fold, P = .031) levels were significantly reduced in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to wild‐type ECs (Figure 4C).

Deregulated JAK2 signaling is associated with chronic inflammation. 49 We measured the levels of interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), two proinflammatory cytokines strongly implicated in promoting CVDs. 7 , 32 , 33 , 37 , 38 , 50 Consistent with the increased inflammatory monocytes (Ly‐6Chigh) in Tie2FF1 mice (Figure 1E), IL‐1β mRNA level was significantly upregulated in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to wild‐type ECs, while no difference was detected in the transcript level of IL‐6 (Figure 4C).

Flow shear stress plays a critical role in endothelial function and atherothrombosis. 51 , 52 We evaluated how the JAK2V617F mutation affects EC response to flow shear stress using primary murine lung ECs (CD45−CD31+) isolated from Tie2‐cre control and Tie2FF1 mice, in part because of their high proliferative activity 53 and close resemblance to cardiac ECs in transcriptional profiling studies. 54 Indeed, similar levels of KLF2/4, TM, eNOS, IL‐1β and IL‐6 deregulation were also obtained in JAK2V617F‐mutant lung ECs (from Tie2FF1 mice) compared to wild‐type lung ECs (from Tie2‐cre mice; data not shown). PECAM and endothelial cell selectin (E‐selection) are two EC adhesion molecules involved in the regulation of thrombus formation, pathogenesis of CVDs, and endothelial response to shear stress. 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 Quantitative flow cytometric analysis revealed that both PECAM (4.9‐fold, P = .038) and E‐selectin (2.6‐fold, P = .038) protein levels were significantly upregulated in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to wild‐type ECs (Figure 4D). We then subjected cultured ECs to pulsatile unidirectional shear stress at 60 dyne/cm2, which mimic the hemodynamic condition of mouse aortic arch blood flow 28 (Figure 4E). We found that both PECAM (2.1‐fold, P = .075) and E‐selectin (2.3‐fold, P = .027) were further upregulated in sheared JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to un‐sheared ECs. In contrast, their levels did not change in wild‐type ECs (Figure 4F and G).

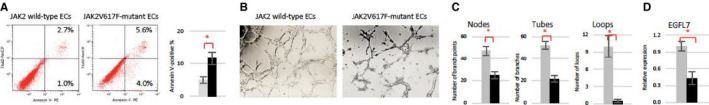

3.5. JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs display a vasculopathy phenotype

As the CVD phenotype does not present in Tie2FF1 mice until after ~20 weeks of age (Figure 1A), we isolated primary murine cardiac ECs (CD45−CD31+) from 22‐ to 24‐week‐old Tie2‐cre and Tie2FF1 mice and examined the effects of JAK2V617F mutation on cardiac EC function. We found that JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs displayed increased cell apoptosis and decreased tube formation (as a measure of in vitro angiogenesis) compared to wild‐type ECs (Figure 5A‐C), which can contribute to the vasculopathy and cardiomyopathy phenotype displayed by the Tie2FF1 mice. Epidermal growth factor‐like domain 7 (EGFL7) is an angiogenic factor exclusively expressed in ECs and controls key steps in vascular tube formation. 60 EGFL7 also represses endothelium activation during inflammatory conditions, and activated endothelium plays an essential part in the adhesion and transendothelial migration of circulating leukocytes into inflamed vascular tissues. 61 We found that EGFL7 mRNA level is significantly reduced in freshly isolated JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs compared to wild‐type ECs (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5.

JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac endothelial cells (ECs) display a vasculopathy phenotype. A, Representative flow cytometry plots (left) and quantitative analysis (right) showing increased apoptosis in cultured JAK2V617F ECs (black bar) compared to wild‐type ECs (gray bar). B, Wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs (8 × 104) were seeded in Matrigel matrix in 48‐well plate. Representative tube formation after a 4‐hour incubation is shown. Magnification: 10×. C, Quantification of tube formation was performed on images taken at 4× magnification by counting the number of nodes (or branch points), tubes, and loops in four non‐overlapping fields. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 4). Data are from one of two independent experiments on two different pairs of cardiac ECs that gave similar results. D, Gene expression level of EGFL7 in wild‐type (gray) and JAK2V617F (black) cardiac ECs measured using real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Gene expression in VF ECs is shown as the fold change compared to the average wild‐type EC expression which was set as “1.” (n = 3 in each group) *P < .05

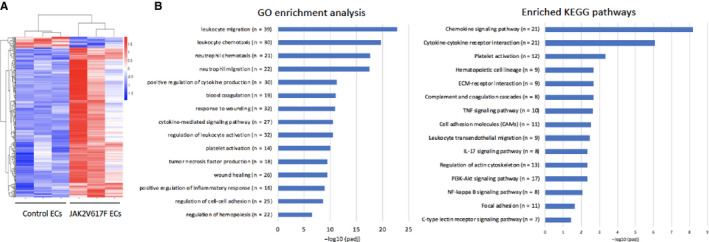

3.6. JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs display a differential expression profile in comparison to wild‐type ECs

To further understand the effects of JAK2V617F mutation on EC function, we performed transcriptomic profiles of wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs using RNA sequencing. Two hundred and thirty‐four genes from a total of 20 698 were differentially expressed (219 up‐ and 15 downregulated) in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to wild‐type ECs. Dysregulation of leukocyte migration/activation/adhesion pathways, platelet activation pathways, and blood coagulation pathways are highly enriched in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs, consistent with the prothrombotic phenotype we have observed in the Tie2FF1 mice. In addition, pathways involved in receptor‐extracellular matrix interaction and leukocyte transendothelial migration/activation were also dysregulated in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs, which can contribute to the vasculopathy phenotype in these mice (Figure 6A and B). These findings supported recent transcriptomic profiling of JAK2V617F‐mutant human ECs derived from induced pluripotent stem cell lines from an MPN patient. 62

FIGURE 6.

Transcriptomic profiling of wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac endothelial cells (ECs). A, Unsupervised hierarchical cluster heatmap of 234 differentially expressed genes between wild‐type and JAK2V617F ECs with an adjusted P‐value < 0.05. B, Differentially enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways in JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs compared to wild‐type control ECs. P values are plotted as the negative of their logarithm

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the substantial progress in our understanding of hemostasis and thrombosis, little is known of the mechanisms that contribute to the hypercoagulability and vascular complications in patients with MPNs, the actual cause of death in the majority of patients who succumb to their illness.

While most of the published studies have focused on mutant blood cells (eg, leukocytes, 33 , 63 , 64 red blood cells 65 , 66 ), two reports highlighted the pro‐adhesive phenotype of JAK2V617F mutant ECs using induced pluripotent stem cell lines from a MPN patient 62 or an endothelial‐specific JAK2V617F‐positive murine model. 67 However, no cardiovascular functional analysis was performed in these two studies. The innovation of our study lies in its growing out of our creating a JAK2V617F‐positive murine model of MPN (Tie2FF1) for other experiments, 20 , 21 where we only expected to see effects of the JAK2V617F‐mutant vascular niche on neoplastic hematopoiesis; unexpectedly, we found that the Tie2FF1 mice, in which the mutation is expressed in both blood cells and vascular ECs, spontaneously develop age‐related DCM with an increased risk of sudden death when fed on a regular chow diet (Figure 1). Pathologic evaluation revealed a prothrombotic, vasculopathy, and cardiomyopathy phenotype in Tie2FF1 mice. No significant myocardium infarctions were detected in Tie2FF1 mice. Therefore, massive pulmonary embolism and/or malignant ventricular arrythmia due to severely decreased LV systolic function are likely the causes of sudden death in these mice, though other causes (eg cerebrovascular events) cannot be excluded. It is important to note that MPN is uncommon before the age of 50 years in human. 68 In our Tie2FF1 mice, despite the presence of JAK2V617F mutation, cardiovascular phenotype (ie, decreased ejection fraction, increased incidence of sudden death) did not present until 20 weeks of age. These observations suggest that the process of aging can modify the cardiovascular risks associated with the JAK2V617F mutation.

Vascular ECs play critical roles in the regulation of hemostasis and thrombosis. 10 Whether endothelial dysfunction contributes to CVDs in CHIP and MPN patients is not known. Over the past 2 years, in studies designed to better understand heart disease in individuals with CHIP, it has been reported that CVD (eg, atherosclerosis, heart failure) can develop in murine models with hematologic mutations (eg, TET2, JAK2V617F) when the mice are challenged with additional risk factors (eg, high‐fat/high‐cholesterol diet, 7 , 37 surgical ligation/constriction of the coronary artery or aorta, 32 , 33 or hyperlipidemia genetic background via knocking‐out of low‐density lipoprotein receptor 38 ). In contrast, our Tie2FF1 mice (with both JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells and JAK2V617F‐mutant vascular ECs) develop CVD spontaneously when fed on regular chow diet. These observations suggest that JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs can accelerate cardiovascular pathology in this murine model of JAK2V617F‐positive MPN. Transplantation of Tie2FF1 bone marrow (with JAK2V617F‐mutant blood cells) into wild‐type mice (with wild‐type vascular ECs) fails to produce cardiac dysfunction, suggesting that JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs are required for the cardiovascular disease phenotype we have observed.

To shed light on the mechanisms underlying the JAK2V617F‐induced endothelial dysfunction, we showed that: (a) both the inflammatory Ly‐6Chigh monocytes, which are important participants at various stages of CVD progression and complication, 31 , 32 , 33 and IL‐1β, a pro‐inflammatory cytokine strongly implicated in promoting CVDs, 8 , 69 are upregulated in the Tie2FF1 mice compared to control mice (Figures 1 and 4); (b) the key endothelial function regulators KLF2, KLF4, TM, eNOS, and EGFL7 levels were significantly downregulated in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs compared to wild‐type ECs (Figures 4 and 5); (c) the cell surface adhesion molecules PECAM and E‐selectin were significantly upregulated in the mutant ECs and JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs respond to flow shear stress differently than wild‐type ECs (Figure 4); and (d) there were significantly increased apoptosis and decreased tube formation of the JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs compared to wild‐type ECs in vitro (Figure 5), and there were both micro‐ and macro‐coronary vasculopathy in the Tie2FF1 mice in vivo (Figure 2). Of particular interest is the downregulation of EGFL7, which is an EC‐exclusive angiogenic factor important for regulating angiogenesis and repressing EC activation during inflammation. 60 , 61 Because deregulated JAK2 signaling is associated with chronic inflammation 49 and there is a pro‐inflammatory phenotype (ie, increased Ly‐6Chigh inflammatory monocytes in peripheral blood and upregulated IL‐1β expression in JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs) in the Tie2FF1 mice, we hypothesize that the JAK2V617F mutation promotes endothelial dysfunction through upregulated inflammatory cytokines (eg IL‐1β) and downregulated angiogenic factors (eg EGFL7). Taken together, these results support our initial hypothesis that JAK2V617F mutation alters endothelial function to promote cardiovascular complications in this MPN‐murine model.

Previously, Shi et al and Zhao et al reported cardiomegaly 70 and vascular thrombosis 65 , 70 on histology examination (no functional evaluation of cardiovascular function was provided) in two JAK2V167F‐positive murine models of MPN in which the mutation is expressed only in blood cells. One possible explanation for the difference between our observation and Shi et al and Zhao et al's studies is the marked erythrocytosis present in their murine models, 65 , 70 which is a primary determinant of blood viscosity and a contributor to vascular complications in patients with MPNs. 71 Due to the limitation of Tie2‐cre murine model which has the Cre recombinase expressed in both hematopoietic cells and endothelial cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that the JAK2V617F mutation alters endothelial–leukocyte interactions 46 , 72 to promote cardiovascular dysfunction in Tie2FF1 mice. While EC mutation is indispensable in our model (Figure 3), JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs alone might not be sufficient to generate the spontaneous cardiovascular phenotype we have observed. Indeed, transcriptomic profiling of wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant cardiac ECs revealed significant upregulation of leukocyte migration, activation, and adhesion pathways in the mutant ECs (Figure 6), suggesting that contribution of altered endothelial–leukocyte interactions may have an important role in JAK2V617F‐induced CVDs. Although we only examined the JAK2V617F mutation in the Tie2FF1 murine model while there are other genetic mutations (eg, MPL, CALR) involved in the human disease, an activated JAK–STAT signaling plays a central role in MPN pathogenesis. 72 An endothelial‐specific Cre model (eg VE‐cadherin‐creERT2) 73 , 74 , 75 will be required to further investigate the mechanistic link between endothelial mutation and the prominent cardiovascular risks seen in patients with JAK2V617F‐positive CHIP and MPNs. In addition, because vascular ECs in patients with MPNs are likely heterogeneous with both normal and JAK2V167F‐mutant ECs, 12 a murine model with chimeric vascular endothelium (ie, with both wild‐type and JAK2V617F‐mutant ECs) will better demonstrate the human disease state.

Though a common origin between blood and endothelium beyond the embryonic stage of development continues to be a subject of intense investigation, hematopoietic mutations can be detected in ECs in many hematologic malignancies including MPNs. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 76 , 77 , 78 Taken together with recent reports of the pro‐adhesive phenotype of JAK2V617F mutant ECs, 62 , 67 our work suggests that the JAK2V617F mutation can alter endothelial function to promote cardiovascular complications including thrombosis, vasculopathy, and cardiomyopathy in MPNs. The findings from this study provide a new approach to investigate vascular pathology in other hematologic malignancies in which ECs are involved in the malignant process. 76 , 77 , 78

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exists.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M Castiglione performed various in vitro and in vivo experiments of the project; C Mazzeo and S Lee performed/assisted various in vitro experiments involving the JAK2V617F‐mutant lung and cardiac ECs; Y‐P Jiang, J‐S Chen, and RZ Lin performed/assisted murine echocardiography studies; W Yin performed/assisted in vitro flow shear stress experiments; KK reviewed data and revised the manuscript; H Zheng assisted various cardiovascular histology analysis, reviewed echocardiography data, and revised the manuscript. H Zhan designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant NIH R01 HL134970 (HZ), VA Career Development Award BX001559 (HZ), and VA Merit Award BX003947 (HZ).

Castiglione M, Jiang Y‐P, Mazzeo C, et al. Endothelial JAK2V617F mutation leads to thrombosis, vasculopathy, and cardiomyopathy in a murine model of myeloproliferative neoplasm. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:3359–3370. 10.1111/jth.15095

Manuscript handled by: Katsue Suzuki‐Inoue

Final decision: Katsue Suzuki‐Inoue, 02 September 2020

REFERENCES

- 1. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Falanga A. Thrombosis in myeloproliferative disorders: pathogenetic facts and speculation. Leukemia. 2008;22:2020‐2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhan H, Kaushansky K. Functional interdependence of hematopoietic stem cells and their niche in oncogene promotion of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 159th biomedical version of "it takes two to tango". Exp Hematol. 2019;70:24‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, et al. Age‐related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20:1472‐1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Genovese G, Kahler AK, Handsaker RE, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood‐cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2477‐2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age‐related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2488‐2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKerrell T, Park N, Moreno T, et al. Leukemia‐associated somatic mutations drive distinct patterns of age‐related clonal hemopoiesis. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1239‐1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:111‐121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Libby P, Ebert BL. CHIP (Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential). Circulation. 2018;138:666‐668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jaiswal S, Ebert BL. Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science. 2019;366:eaan4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu KK, Thiagarajan P. Role of endothelium in thrombosis and hemostasis. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:315‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sozer S, Fiel MI, Schiano T, Xu M, Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R. The presence of JAK2V617F mutation in the liver endothelial cells of patients with Budd‐Chiari syndrome. Blood. 2009;113:5246‐5249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosti V, Villani L, Riboni R, et al. Spleen endothelial cells from patients with myelofibrosis harbor the JAK2V617F mutation. Blood. 2013;121:360‐368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yoder MC, Mead LE, Prater D, et al. Redefining endothelial progenitor cells via clonal analysis and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell principals. Blood. 2007;109:1801‐1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teofili L, Martini M, Iachininoto MG, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells are clonal and exhibit the JAK2(V617F) mutation in a subset of thrombotic patients with Ph‐negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;117:2700‐2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piaggio G, Rosti V, Corselli M, et al. Endothelial colony‐forming cells from patients with chronic myeloproliferative disorders lack the disease‐specific molecular clonality marker. Blood. 2009;114:3127‐3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helman R, Pereira WO, Marti LC, et al. Granulocyte whole exome sequencing and endothelial JAK2V617F in patients with JAK2V617F positive Budd‐Chiari Syndrome without myeloproliferative neoplasm. Br J Haematol. 2018;180:443‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tiedt R, Hao‐Shen H, Sobas MA, et al. Ratio of mutant JAK2‐V617F to wild‐type Jak2 determines the MPD phenotypes in transgenic mice. Blood. 2008;111:3931‐3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Constien R, Forde A, Liliensiek B, et al. Characterization of a novel EGFP reporter mouse to monitor Cre recombination as demonstrated by a Tie2 Cre mouse line. Genesis. 2001;30:36‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Etheridge SL, Roh ME, Cosgrove ME, et al. JAK2V617F‐positive endothelial cells contribute to clotting abnormalities in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2295‐2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhan H, Lin CHS, Segal Y, Kaushansky K. The JAK2V617F‐bearing vascular niche promotes clonal expansion in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2018;32:462‐469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin CHS, Zhang Y, Kaushansky K, Zhan H. JAK2V617F‐bearing vascular niche enhances malignant hematopoietic regeneration following radiation injury. Haematologica. 2018;103:1160‐1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao S, Ho D, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. Echocardiography in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2011;1:71‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hiemann NE, Wellnhofer E, Knosalla C, et al. Prognostic impact of microvasculopathy on survival after heart transplantation: evidence from 9713 endomyocardial biopsies. Circulation. 2007;116:1274‐1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhan H, Ma Y, Lin CH, Kaushansky K. JAK2V617F‐mutant megakaryocytes contribute to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell expansion in a model of murine myeloproliferation. Leukemia. 2016;30:2332‐2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin CH, Kaushansky K, Zhan H. JAK2V617F‐mutant vascular niche contributes to JAK2V617F clonal expansion in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;62:42‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meza D, Abejar L, Rubenstein DA, Yin W. A shearing‐stretching device that can apply physiological fluid shear stress and cyclic stretch concurrently to endothelial cells. J Biomech Eng. 2016;138:4032550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meza D, Shanmugavelayudam SK, Mendoza A, Sanchez C, Rubenstein DA, Yin W. Platelets modulate endothelial cell response to dynamic shear stress through PECAM‐1. Thromb Res. 2017;150:44‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suo J, Ferrara DE, Sorescu D, Guldberg RE, Taylor WR, Giddens DP. Hemodynamic shear stresses in mouse aortas: implications for atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:346‐351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gan XT, Rajapurohitam V, Xue J, et al. Myocardial hypertrophic remodeling and impaired left ventricular function in mice with a cardiac‐specific deletion of Janus kinase 2. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:3202‐3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Foshay K, Rodriguez G, Hoel B, Narayan J, Gallicano GI. JAK2/STAT3 directs cardiomyogenesis within murine embryonic stem cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2005;23:530‐543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161‐166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, et al. Tet2‐mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates heart failure through a mechanism involving the IL‐1beta/NLRP3 inflammasome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:875‐886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sano S, Wang Y, Yura Y, et al. JAK2 (V617F)‐mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates pathological remodeling in murine heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4:684‐697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Giordano NJ, Jansson PS, Young MN, Hagan KA, Kabrhel C. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, stratification, and natural history of pulmonary embolism. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;20:135‐140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwartz RS, Burke A, Farb A, et al. Microemboli and microvascular obstruction in acute coronary thrombosis and sudden coronary death: relation to epicardial plaque histopathology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2167‐2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2825‐2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science. 2017;355:842‐847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang W, Liu W, Fidler T, et al. Macrophage inflammation, erythrophagocytosis, and accelerated atherosclerosis in Jak2 (V617F) mice. Circ Res. 2018;123:e35‐e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhan H, Ma Y, Lin CH, Kaushansky K. JAK2(V617F)‐mutant megakaryocytes contribute to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell expansion in a model of murine myeloproliferation. Leukemia. 2016;30:2332‐2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stroka KM, Aranda‐Espinoza H. Effects of morphology vs. cell‐cell interactions on endothelial cell stiffness. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2011;4:9‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Califano JP, Reinhart‐King CA. Substrate stiffness and cell area predict cellular traction stresses in single cells and cells in contact. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2010;3:68‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. van Thienen JV, Fledderus JO, Dekker RJ, et al. Shear stress sustains atheroprotective endothelial KLF2 expression more potently than statins through mRNA stabilization. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:231‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhou G, Hamik A, Nayak L, et al. Endothelial Kruppel‐like factor 4 protects against atherothrombosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4727‐4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Esmon CT. The protein C anticoagulant pathway. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:135‐145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Svensson PJ, Dahlback B. Resistance to activated protein C as a basis for venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:517‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kubes P, Suzuki M, Granger DN. Nitric oxide: an endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4651‐4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Garg UC, Hassid A. Nitric oxide‐generating vasodilators and 8‐bromo‐cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibit mitogenesis and proliferation of cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1774‐1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Siragusa M, Fleming I. The eNOS signalosome and its link to endothelial dysfunction. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:1125‐1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Perner F, Perner C, Ernst T, Heidel FH. Roles of JAK2 in aging, inflammation, hematopoiesis and malignant transformation. Cells. 2019;8:854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Walsh K. CRISPR‐mediated gene editing to assess the roles of Tet2 and Dnmt3a in clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2018;123:335‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chiu JJ, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:327‐387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bai L, Shyy JYP. Shear stress regulation of endothelium: a double‐edged sword. J Transl Int Med. 2018;6:58‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Basile DP, Yoder MC. Circulating and tissue resident endothelial progenitor cells. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:10‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nolan DJ, Ginsberg M, Israely E, et al. Molecular signatures of tissue‐specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Dev Cell. 2013;26:204‐219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. Endothelial PECAM‐1 and its function in vascular physiology and atherogenic pathology. Exp Mol Pathol. 2016;100:409‐415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harry BL, Sanders JM, Feaver RE, et al. Endothelial cell PECAM‐1 promotes atherosclerotic lesions in areas of disturbed flow in ApoE‐deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:2003‐2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Telen MJ. Cellular adhesion and the endothelium: E‐selectin, L‐selectin, and pan‐selectin inhibitors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:341‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Dixit M, Busse R. Role of PECAM‐1 in the shear‐stress‐induced activation of Akt and the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4103‐4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Huang RB, Eniola‐Adefeso O. Shear stress modulation of IL‐1beta‐induced E‐selectin expression in human endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Parker LH, Schmidt M, Jin SW, et al. The endothelial‐cell‐derived secreted factor Egfl7 regulates vascular tube formation. Nature. 2004;428:754‐758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pinte S, Caetano B, Le Bras A, et al. Endothelial cell activation is regulated by epidermal growth factor‐like domain 7 (Egfl7) during inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:24017‐24028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guadall A, Lesteven E, Letort G, et al. Endothelial cells harbouring the JAK2V617F mutation display pro‐adherent and pro‐thrombotic features. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118:1586‐1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wolach O, Sellar RS, Martinod K, et al. Increased neutrophil extracellular trap formation promotes thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaan8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Edelmann B, Gupta N, Schnoeder TM, et al. JAK2‐V617F promotes venous thrombosis through beta1/beta2 integrin activation. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:4359‐4371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhao B, Mei Y, Cao L, et al. Loss of pleckstrin‐2 reverts lethality and vascular occlusions in JAK2V617F‐positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:125‐140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Poisson J, Tanguy M, Davy H, et al. Erythrocyte‐derived microvesicles induce arterial spasms in JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2630‐2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guy A, Gourdou‐Latyszenok V, Le Lay N, et al. Vascular endothelial cell expression of JAK2(V617F) is sufficient to promote a pro‐thrombotic state due to increased P‐selectin expression. Haematologica. 2019;104:70‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Spivak JL. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2168‐2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Libby P, Everett BM. Novel antiatherosclerotic therapies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:538‐545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shi K, Zhao W, Chen Y, Ho WT, Yang P, Zhao ZJ. Cardiac hypertrophy associated with myeloproliferative neoplasms in JAK2V617F transgenic mice. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pearson TC, Wetherley‐Mein G. Vascular occlusive episodes and venous haematocrit in primary proliferative polycythaemia. Lancet. 1978;2:1219‐1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rampal R, Al‐Shahrour F, Abdel‐Wahab O, et al. Integrated genomic analysis illustrates the central role of JAK‐STAT pathway activation in myeloproliferative neoplasm pathogenesis. Blood. 2014;123:e123‐e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Monvoisin A, Alva JA, Hofmann JJ, Zovein AC, Lane TF, Iruela‐Arispe ML. VE‐cadherin‐CreERT2 transgenic mouse: a model for inducible recombination in the endothelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:3413‐3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sorensen I, Adams RH, Gossler A. DLL1‐mediated Notch activation regulates endothelial identity in mouse fetal arteries. Blood. 2009;113:5680‐5688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kilani B, Gourdou‐Latyszenok V, Guy A, et al. Comparison of endothelial promoter efficiency and specificity in mice reveals a subset of Pdgfb‐positive hematopoietic cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:827‐840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Streubel B, Chott A, Huber D, et al. Lymphoma‐specific genetic aberrations in microvascular endothelial cells in B‐cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:250‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fang B, Zheng C, Liao L, et al. Identification of human chronic myelogenous leukemia progenitor cells with hemangioblastic characteristics. Blood. 2005;105:2733‐2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rigolin GM, Fraulini C, Ciccone M, et al. Neoplastic circulating endothelial cells in multiple myeloma with 13q14 deletion. Blood. 2006;107:2531‐2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]