Abstract

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) methodology standards for qualitative methods and mixed methods research help ensure that research studies are designed and conducted to generate the evidence needed to answer patients’ and clinicians’ questions about which methods work best, for whom, and under what circumstances. This set of standards focuses on factors pertinent to patient centered outcomes research, but it is also useful for providing guidance for other types of clinical research. The standards can be used to develop and evaluate proposals, conduct the research, and interpret findings. The standards were developed following a systematic process: survey the range of key methodological issues and potential standards, narrow inclusion to standards deemed most important, draft preliminary standards, solicit feedback from a content expert panel and the broader public, and use this feedback to develop final standards for review and adoption by PCORI’s board of governors. This article provides an example on how to apply the standards in the preparation of a research proposal.

Rigorous methodologies are critical for ensuring the trustworthiness of research results. This paper will describe the process for synthesizing the current literature providing guidance on the use of qualitative and mixed methods in health research; and the process for development of methodology standards for qualitative and mixed methods used in patient centered outcomes research. Patient centered outcomes research is comparative clinical effectiveness research that aims to evaluate the clinical outcomes resulting from alternative clinical or care delivery approaches for fulfilling specific health and healthcare needs. By focusing on outcomes that are meaningful to patients, studies on patient centered outcomes research strengthen the evidence base and inform the health and healthcare decisions made by patients, clinicians, and other stakeholders.

The methods used in patient centered outcomes research are diverse and often include qualitative methodologies. Broadly, qualitative research is a method of inquiry used to generate and analyze open ended textual data to enhance the understanding of a phenomenon by identifying underlying reasons, opinions, and motivations for behavior. Many different methodologies can be used in qualitative research, each with its own set of frameworks and procedures.1 This multitude of qualitative approaches allows investigators to select and synergize methods with the specific needs associated with the aims of the study.

Qualitative methods can also be used to supplement and understand quantitative results; the integration of these approaches for scientific inquiry and evaluation is known as mixed methods.2 This type of approach is determined a priori, because the research question drives the choice of methods, and draws on the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches to resolve complex and contemporary issues in health services. This strategyis achieved by integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches at the design, methods, interpretation, and reporting levels of research.3 Table 1 lists definitions of qualitative methods, mixed methods, and patient centered outcomes research. The methodology standards described here are intended to improve the rigor and transparency of investigations that include qualitative and mixed methods. The standards apply to designing projects, conducting the studies, and reporting the results. Owing to its focus on patient centered outcomes research, this article is not intended to be a comprehensive summary of the difficulties encountered in the conduct of qualitative and mixed methods research.

Table 1.

Terms and definitions used in the development of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) qualitative and mixed methods research methodology standards

| Term | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Patient centered outcomes research (PCOR) | Research guided by those who will use the information and centered around outcomes important to patients; PCOR studies aim to help patients and caregivers make better informed decisions about the healthcare choices they face | PCORI4 |

| Comparative effectiveness research | Generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care. Comparative effectiveness research aims to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve healthcare at both the individual and population levels | Institute of Medicine5 |

| Qualitative methods research | An approach to inquiry and evaluation that gathers non-numerical data, such as focus groups and interviews, which aims to characterize people’s beliefs, attitudes, experience, behaviors, and interactions to achieve a depth and richness of information about a research area of study | Crabtree and Miller6 |

| Trustworthiness | Extent to which the investigative process establishes the study’s findings are credible, transferable, and confirmable, thereby ensuring reliability of its findings and enabling the replication of the processes and results | Creswell and Miller7 |

| Credibility | Establishing the integrity of the research process to ensure a high level of confidence in the accuracy and validity of the findings | Crabtree and Miller6; Creswell and Miller7 |

| Reflexivity | Process of systematically attending to and recording the process of knowledge construction that addresses the influence or effect of the researcher’s own beliefs and attitudes at every step of the research process | Malterud8 |

| Negative or deviant case analysis | Process of exploring cases that run counter to emerging theories of conclusions, in order to include cases that might not fit an emerging perspective and thereby revising, broadening, or confirming emerging patterns from data analysis | Patton9 |

| Member checking | Validation technique and process of proving or disproving a finding through exploring the credibility of results by returning the data to the participants | Creswell and Poth10 |

| Triangulation | Use of different methods (eg, interviews and focus groups) or experts with different backgrounds (eg, anthropology and nursing) in one study, which enables a richer account of the narrative | Creswell and Poth10; Patton11 |

| Audit trail | Providing detail about data collection and analysis so that readers can fully understand the process, such as a clear definition of methods, meticulous documentation of data collection and data analysis, details on coding strategies, and the codebook development process (eg, when conducting an audit trail for the coding process, researchers document the creation of codes, as well as the collapsing or splitting of codes so that a full inventory of the coding process can be produced) | Creswell and Poth10 |

| Mixed methods research | Inquiry and evaluation that is driven by the research question and a priori deliberately integrates quantitative and qualitative methods from inception to analysis to provide a broader perspective than with a single method approach alone | Creswell et al12 |

| Integration | Process of incorporating or linking qualitative and quantitative components at every level in the research process; from design to methods, interpretation, and reporting, each component of qualitative and quantitative efforts informs and guides the other | Fetters et al3 |

Summary points.

Many publications provide guidance on how to use qualitative and mixed methods in health research

The methodological standards reported here and adopted by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) synthesize and refine various recommendations to improve the design, conduct, and reporting of patient centered, comparative, clinical effectiveness research

PCORI has developed and adopted standards that provide guidance on key areas where research applications and research reports have been deficient in the plans for and use of qualitative and mixed methods in conducting patient centered outcomes research

The standards provide guidance to health researchers to ensure that studies of this research are designed and conducted to generate valid evidence needed to analyze patients’ and clinicians’ questions about what works best, for whom, and under what circumstances

Background

Established by the United States Congress in 201013 and reauthorized in 2019,14 the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funds scientifically rigorous comparative effectiveness research, previously defined as patient centered outcomes research, to improve the quality and relevance of evidence that patients, care givers, clinicians, payers, and policy makers need to make informed healthcare decisions. Such decisions might include choices about which prevention strategies, diagnostic methods, and treatment options are most appropriate based on personal preferences and unique patient characteristics.

PCORI’s focus on patient centeredness and stakeholder engagement in research has generated increased interest in and use of methodologies of qualitative and mixed methods research within comparative effectiveness research studies. Qualitative data have a central role in understanding the human experience. As with any research, the potential for these studies to generate high integrity, evidence based information depends on the quality of the methods and approaches that were used. PCORI’s authorizing legislation places a unique emphasis on ensuring scientific rigor, including the creation of a methodology committee that develops and approves methodology standards to guide PCORI funded research.13 The methodology committee consists of 15 individuals who were appointed by the Comptroller General of the US and the directors of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health. The members of the committee are medical and public health professionals with expertise in study design and methodology for comparative effectiveness research or patient centered outcomes research (https://www.pcori.org/about-us/governance/methodology-committee).

The methodology committee began developing its initial group of methodology standards in 2012 (with adoption by the PCORI’s board of governors that year). Since then, the committee has revised and expanded the standards based on identified methodological issues and input from stakeholders. Before the adoption of the qualitative and mixed methods research standards, the PCORI methodology standards consisted of 56 individual standards in 13 categories.15 The first five categories of the standards are crosscutting and relevant to most studies on patient centered outcomes research, while the other eight categories are applicable depending on a study’s purpose and design.15

Departures from good research practices are partially responsible for weaknesses in the quality and subsequent relevance of research. The PCORI methodology standards provide guidance that helps to ensure that studies on patient centered outcomes research are designed and conducted to generate the evidence needed to answer patients’ and clinicians’ questions about what works best, for whom, and under what circumstances. These standards do not represent a complete, comprehensive set of all requirements for high quality patient centered outcomes research; rather, they cover topics that are likely to contribute to improvements in quality and value. Specifically, the standards focus on selected methodological issues that have substantial deficiencies or inconsistencies regarding how available methods are applied in practice. These methodological issues might include a lack of rigor or inappropriate use of approaches for conducting patient centered outcomes research. As a research funder, PCORI uses the standards in the scientific review of applications, monitoring of funded research projects, and evaluation of final reports of research findings.

Use of qualitative methods has become more prevalent over time. Based on a PubMed search in June 2020 (search terms “qualitative methods” and “mixed methods”), the publication of qualitative and mixed methods studies has grown steadily from 1980 to 2019. From 1980 to 1989, 63 qualitative and 110 mixed methods papers were identified. Between 1990 to 1999, the number of qualitative and mixed methods papers was 420 and 58, respectively; by 2010 to 2019, these numbers increased to 5481 and 17 031, respectively. The prominent increase in publications in recent years could be associated with more sophisticated indexing methods in PubMed as well as the recognition that both qualitative and mixed methods research are important approaches to scientific inquiry within the health sciences. These approaches allow investigators to obtain a more detailed perspective and to incorporate patients’ motivations, beliefs, and values.

Although the use of qualitative and mixed methods research has increased, consensus regarding definitions and application of the methods remain elusive, reflecting wide disciplinary variation.16 17 Many investigators and organizations have attempted to resolve these differences by proposing guidelines and checklists that help define essential components.12 16 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 For example, Treloar et al20 offer direction for qualitative researchers in designing and publishing research by providing a 10 point checklist for assessing the quality of qualitative research in clinical epidemiological studies. Tong et al22 provide a 32 item checklist to help investigators report important aspects of the research process for interviews and focus groups such as the study team, study methods, context of the study, findings, analysis, and interpretations.

The goal of the PCORI Methodology Standards on Qualitative and Mixed Methods is to provide authoritative guidance on the use of these methodologies in comparative effectiveness research and patient centered outcomes research. The purpose of these types of research is to improve the clinical evidence base and, particularly, to help end users understand how the evidence provided by individual research studies can be applied to particular clinical circumstances. Use of qualitative and mixed methods can achieve this goal but can also introduce specific issues that need to be captured in PCORI’s methodological guidance. The previously published guidelines generally have a broader focus and different points of emphasis.

This article describes the process for synthesizing the current literature providing guidance on the use of qualitative and mixed methods in health research; and developing methodology standards for qualitative and mixed methods used in patient centered outcomes research. We then provide an example showing how to apply the standards in the design of a patient centered outcomes research application.

Methodology standards development process

Literature review and synthesis

The purpose of the literature review was to identify published journal articles that defined criteria for rigorous qualitative and mixed methods research in health research. With the guidance of PCORI’s medical librarian, we designed and executed searches in PubMed, and did four different keyword searches for both qualitative and mixed methods (eight searches in total; supplemental table 1). We aimed to identify articles that provided methodological guidance rather than studies that simply used the methods.

We encountered two major challenges. First, qualitative and mixed methods research has a broad set of perspectives.30 31 Second, some medical subject headings (MeSH terms) in our queries were not introduced until recently (eg, “qualitative methods” introduced in 2003, “comparative effectiveness” introduced in 2010), which required us to search for articles by identifying a specific qualitative method (eg, interviews, focus groups) to capture the literature before 2003 (table 1). These challenges could have led to missed publications. To refine and narrow our search results, we applied the following inclusion criteria:

Articles on health services or clinical research, published in English, and published between 1 January 1990 and 14 April 2017

Articles that proposed or discussed a guideline, standard, framework, or set of principles for conducting rigorous qualitative and mixed methods research

Articles that described or discussed the design, methods for, or reporting of qualitative and mixed methods research.

The search queries identified 1933 articles (1070 on qualitative methods and 863 on mixed methods). The initial citation lists were reviewed, and 204 duplicates were removed. Three authors (BG, MH, and AB) manually reviewed the 1729 remaining article abstracts. Titles and abstracts were independently evaluated by each of the three reviewers using the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were adjudicated by an in-person meeting to determine which articles to include. This initial round of review yielded 212 references, for which the full articles were obtained. The full articles were reviewed using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as the abstracts. Most of these articles were studies that had used a qualitative or mixed methods approach but were only reporting on the results of the completed research. Therefore, these articles were not able to inform the development of standards for conducting qualitative and mixed methods research and they were excluded, resulting in the final inclusion of 56 articles (supplemental table 2). Following the original search, the literature was scanned for new articles providing guidance on qualitative and mixed methods, resulting in four articles being added to the final set of literature. These articles come from psychology and health psychology specialties and seek to provide not only minimal standards in relation to qualitative and mixed methods research but also standards for best practice that apply across a wide range of fields.32 33 34 35

Initial set of methodology standards

Using an abstraction form that outlined criteria for qualitative and mixed methods manuscripts and research proposals, we abstracted the articles to identify key themes, recommendations, and guidance under each criterion. Additional information was noted when considered relevant. A comprehensive document was created to include the abstractions and notes for all articles. This document outlined the themes in the literature related to methodological guidance. We began with the broadest set of themes organized into 11 major domains: the theoretical approach, research topics, participants, data collection, analysis and interpretation, data management, validity and reliability, presentation of results, context of research, impact of the researchers (that is, reflexivity), and mixed methods. As our goal was to distill the themes into broad standards that did not overlap with pre-existing PCORI methodology standards, we initially condensed the themes into six qualitative and three mixed methods standards. Following discussion among members of the working group, some standards were combined and two were dropped because of substantial overlap with each other or with previously developed PCORI methodology standards.

The key themes identified from the abstracted information were used as the foundation for the first draft of the new methodology standards. We then further discussed the themes as a team and removed redundancies, refined the labeling of themes, and removed themes deemed extraneous through a team based adjudication process. The draft standards were presented to PCORI’s methodology committee to solicit feedback. Revisions were made on the basis of this feedback.

Expert panel one day workshop

A one day expert panel workshop was held in Washington, DC, on 18 January 2018. Ten individuals regarded as international leaders in qualitative and mixed methods were invited to attend—including those who had created standards previously or had a substantial number of peer reviewed publications reporting qualitative and mixed methods in health research; had many years’ experience as primary researchers; and had served as editors of major textbooks and journals. The panel was selected on the basis of their influence and experience in these methodologies as well as their broad representation from various fields of study. The representation of expertise spanned the fields of healthcare, anthropology, and the social sciences (supplemental table 3).

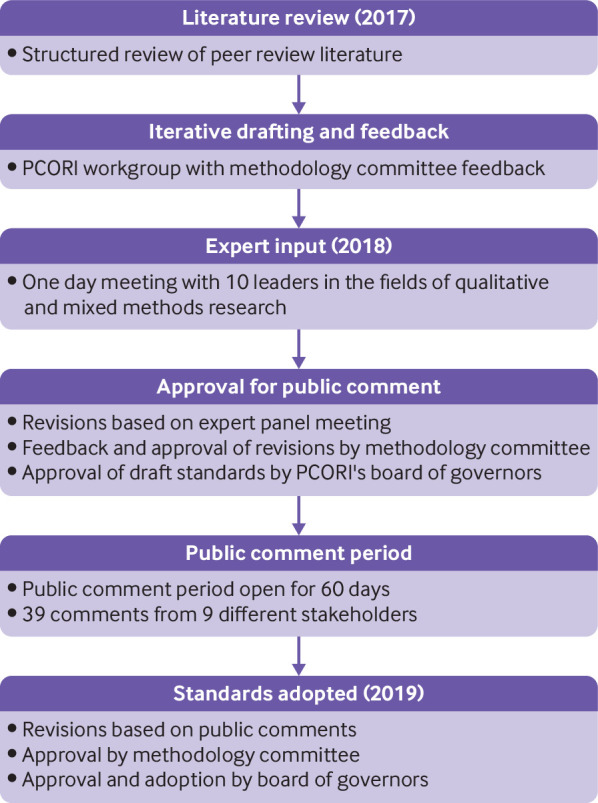

Before the meeting, we emailed the panel members the draft set of qualitative and mixed methods standards, PCORI’s methodology standards document, and the background document describing how the draft standards had been developed. At the meeting, the experts provided extensive feedback, including their recommendations regarding what needs to be done well when using these methodological approaches. The panel emphasized that when conducting mixed methods research, this approach should be selected a priori, based on the research question, and that integration of the mixed approaches is critical at all levels of the research process (from inception to data analysis). The panel emphasized that when conducting qualitative research, flexibility and reflexive iteration should be maintained throughout the process—that is, the sampling, data collection, and data analysis. The main theme from the meeting was that the draft standards were not comprehensive enough to provide guidance for studies on patient centered outcomes research or comparative effectiveness research that involved qualitative and mixed methods. After the conclusion of the workshop, feedback and recommendations were synthesized, and the draft standards were reworked in the spring of 2018 (fig 1). This work resulted in a new set of four qualitative methods standards and three mixed methods standards representing the unique features of each methodology that were not already included in the methodology standards previously adopted by PCORI.

Fig 1.

Process of development and adoption of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) methodology standards on qualitative and mixed methods research

Continued refinement and approval of methodology standards

In late spring 2018, the revised draft methodology standards were presented to PCORI’s methodology committee first by sharing a draft of the standards and then via oral presentation. Feedback from the methodology committee centered around eliminating redundancy in the standards proposed (both across the draft standards and in relation to the previously adopted categories of standards) and making the standards more actionable. The areas where the draft standards overlapped with the current standards were those for formulating research questions, for patient centeredness, and for data integrity and rigorous analyses. Each draft standard was reviewed and assessed by the methodology committee members and the staff workgroup to confirm its unique contribution to PCORI’s methodology standards. After this exercise, each remaining standard was reworded to be primarily action guiding (rather than explanatory). This version of proposed standards was approved by the methodology committee to be sent to PCORI’s board of governors for a vote to approve for public comment. The board of governors approved the standards to be posted for public comment.

The public comment period hosted on PCORI’s website (https://www.pcori.org/engagement/engage-us/provide-input/past-opportunities-provide-input) was held from 24 July 2018 to 21 September 2018. Thirty nine comments were received from nine different stakeholders—seven health researchers, one training institution, and one professional organization. Based on the public comments, minor wording changes were made to most of the draft standards. The final version of the standards underwent review by both the methodology committee and PCORI’s board of governors. The board voted to adopt the final version of the standards on 26 February 2019 (table 2).

Table 2.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) methodology standards for qualitative methods and mixed methods

| Standards for qualitative methods | |

|---|---|

| QM-1: State the qualitative approach to research inquiry, design, and conduct | A. Identify and describe evidence gaps that support the need for a qualitative component(s) of the study B. Identify the qualitative approach (eg, ethnography, grounded theory) that will be used, including the purpose, why it is an appropriate approach to answer the research question(s), and how it will be operationalized C. Describe the types of data to be collected, strategies for data collection (eg, focus groups, observations, interviews, documents, audio or video recordings), and when the data will be collected D. Describe how confidentiality will be maintained through data collection, management, analysis, and reporting E. State the computer software program used to assist with analysis |

| QM-2: Select and justify appropriate qualitative methods sampling strategy | A. Describe and provide the rationale for the sampling strategy (see RQ-3†, RQ-4†, and PC-2‡), including how the strategy flows logically from the qualitative approach and how it fits the research question(s) B. Explain the anticipated sample size, detail any variation in sampling that may occur over the course of study, and state the criteria for deciding when no further sampling is necessary (eg, thematic saturation) C. Describe how the methods will ensure that the data capture the depth of experiences of the participants or phenomenon of interest (see PC-2‡ and PC-3‡) |

| QM-3: Link the qualitative data analysis, interpretations, and conclusions to the study question | A. State who will be involved in the data analysis and interpretation and describe how their qualifications, training, and expertise equip them to understand and address the complexities and challenges unique to qualitative methods B. Describe data analysis procedures and their link to the study’s research questions C. Describe the process by which inferences and themes will be identified and developed as well as how this process is congruent with the chosen qualitative approach and its methodology D. Describe how conclusions will be derived and how they relate to interpretations and content of the original data |

| QM-4: Establish trustworthiness* and credibility of qualitative research | A. State how documentation regarding all phases of the analysis will be captured. Multiple data collection methods (eg, interviews, focus groups, observations) and/or experts with diverse backgrounds can be used to increase trustworthiness, in addition to an inter-coder reliability process B. To enhance credibility, discuss three distinct elements: rigorous techniques and methods, the role of the qualitative researcher, and the value of participants’ perspectives and experiences. Credibility must be explained (see RQ-1†, RQ-2†, and IR-7§) and demonstrated in the analysis in at least one of the following three ways: reflexivity, negative case analysis, and/or member checking |

| Standards for mixed methods research | |

| MM-1: Specify how mixed methods are integrated across design, data sources, and/or data collection phases | A. State which mixed methods approach will be used and describe how it will inform the study procedures B. Describe whether the quantitative and qualitative methods will be sequential, concurrent, or a mixture of both, over time C. Describe how the mixed methods design will integrate qualitative and quantitative approaches at one or more stages of the research process and achieve the intent of the design (eg, by aligning the aims to data collection instruments, procedures and analyses of data, and interpretation of the findings) |

| MM-2: Select and justify appropriate mixed methods sampling strategy | A. Provide a clear description of the relationship between the sampling techniques and the generation of different types of data (eg, numeric or closed ended v narrative or open ended; see RQ-3†, RQ-4†, and QM-2¶) B. Describe the sampling strategies and outline the temporality with which they will take place as they relate to selected qualitative and quantitative methodologies (see IR-1§, IR-2§, PC-2‡, PC-3‡, and QM-1¶), including a justification of the emergence of other samples that may arise during the study, as applicable |

| MM-3: Integrate data analysis, data interpretation, and conclusions | A. Describe the analytic approaches to integration and demonstrate how the analysis plan is congruent with the study design and aims, and that it has been developed based on the methodological approach (eg, either a priori or emergently; see IR-1§, IR-2§, PC-2‡, PC-3‡, QM-1¶, and QM-3¶) B. Identify the order of study components and the points of integration. State who will conduct the integration; describe how their qualifications, training, and expertise equip them to understand and address the complexities and challenges unique to mixed methods analysis; and state how integrated analyses will proceed in terms of the qualitative and quantitative components C. Describe the approach used to interpret integrated data and how conclusions are supported by the context of original qualitative and quantitative findings. Address divergent findings from both qualitative and quantitative components, as well as method-specific biases across the methods (see QM-4¶) |

Trustworthiness focuses on consistency and whether the results would be the same if replicated by others. To determine trustworthiness, describe a detailed audit trail, while maintaining fairness, balance, and neutrality.

Standards for formulating research questions: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#Formulating%20Research%20Questions.

Standards associated with patient centeredness: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#Associated%20with%20Patient-Centeredness.

Standards for data integrity and rigorous analyses: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#Data%20Integrity%20and%20Rigorous%20Analyses.

Standards for qualitative methods: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#QualitativeMethods.

Application of methodology standards in research design

The standards can be used across the research continuum, from research design and application development, conduct of the research, and reporting of research findings. We provide an example for researchers on how these standards can be used in the preparation of a research application (table 3).

Table 3.

Guidance for researchers on how to use Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) methodology standards for qualitative and mixed methods research in application preparation

| Application preparation* | |

|---|---|

| Background | Describe the impact of the condition or phenomenon of interest on the health of individuals and populations. Identify and describe evidence gaps that support the need for a qualitative component (QM-1, A) or mixed methods approach of the study (MM-1, A). State the overall goal that addresses the overarching research problem and proposed research question(s). Ensure that the goal informs the research question(s) and specific aims, leading naturally to a qualitative or mixed methods approach. |

| Research questions and specific aims | State the question(s) the research is designed to address. Describe the specific aims of the study. |

| Significance | Identify rationale for using qualitative or mixed methods data to address the research question and describe how the study findings will enhance the scientific knowledge. |

| Study design or approach | Describe the research strategy or methodological approach, including a clear conceptual framework, theory, or model that anchors the background and significance and informs the design. Identify the qualitative approach (eg, ethnography, grounded theory) that will be used, including the purpose, why it is an appropriate approach to answer the research question(s), and how it will be operationalized (QM-1, B). For mixed methods studies describe whether the quantitative and qualitative methods will be sequential, concurrent, or a mixture of both, over time (MM-1, B). Qualitative sampling: Describe and provide the rationale for the sampling strategy, including how the strategy flows logically from the qualitative approach and how it fits the research question(s) (QM-2, A). Explain the anticipated sample size and state the criteria for deciding when no further sampling is necessary (eg, thematic saturation) (QM-2, B). Describe how the methods will ensure that the data capture the depth of experiences of the participants or phenomenon of interest (QM-2, C). Mixed methods sampling: Provide a clear description of the relationship between the sampling techniques and the generation of different types of data (eg, numeric or closed ended v narrative or open ended) (MM-1, A). Describe the sampling strategies and outline the temporality with which they will take place as they relate to selected qualitative and quantitative methodologies, including a justification of the emergence of other samples that may arise during the study, as applicable (MM-2, B). Qualitative studies: Describe the types of data to be collected, strategies for data collection (eg, focus groups, observations, interviews, documents, audio or video recordings), and when the data will be collected (QM-1, C). Mixed methods studies: Describe how the mixed methods design will integrate qualitative and quantitative approaches at one or more stages of the research process and achieve the intent of the design (eg, by aligning the aims to data collection instruments, procedures and analyses of data, and interpretation of the findings) (MM-1, C). Describe how confidentiality will be maintained through data collection, management, analysis, and reporting (QM-1, D). Trustworthiness focuses on consistency and whether the results would be the same if replicated by others. To determine trustworthiness, describe a detailed audit trail, while maintaining fairness, balance, and neutrality. State how documentation regarding all phases of the analysis will be captured. Multiple data collection methods (eg, interviews, focus groups, observations) and/or experts with diverse backgrounds can be used to increase trustworthiness, in addition to an inter-coder reliability process (QM-4, A). To enhance credibility, discuss three distinct elements: rigorous techniques and methods, the role of the qualitative researcher, and the value of participants’ perspectives and experiences. Credibility must be explained and demonstrated in the analysis in at least one of the following three ways: audit trail, reflexivity, negative case analysis, triangulation, and/or member checking (QM-4, B). |

| Analytic plan | Describe specific plans for data analysis that correspond to major aims. State who will be involved in the data analysis and interpretation and describe how their qualifications, training, and expertise equip them to understand and address the complexities and challenges unique to qualitative methods (QM-3, A). Describe data analysis procedures and their link to the study’s research questions (QM-3, B). This includes data preparation procedures including recording and transcription of data. Coding and theme development strategies should be described. Describe the process by which inferences, and themes will be identified and developed as well as how this process is congruent with the chosen qualitative approach and its methodology (QM-3, C). Describe how conclusions will be derived and how they relate to interpretations and content of the original data (QM-3, D). For mixed methods studies: Describe the analytic approaches to integration and demonstrate how the analysis plan is congruent with the study design and aims, and that it has been developed based on the methodological approach (MM-3, A). Identify the order of study components and the points of integration. State who will conduct the integration; describe how their qualifications, training, and expertise equip them to understand and address the complexities and challenges unique to mixed methods analysis; and state how integrated analyses will proceed in terms of the qualitative and quantitative components (MM-3, B). Describe the approach used to interpret integrated data and how conclusions are supported by the context of original qualitative and quantitative findings. Address divergent findings from both qualitative and quantitative components, as well as method specific biases across the methods (MM-3, C). State the computer software program used to assist with analysis (QM-1, E). |

| Patient and stakeholder engagement | Describe the plan to engage patients and stakeholders meaningfully in the various phases of the proposed research, identify the patient and other stakeholder partners (individuals or organizations) who will be involved, provide the rationale for their inclusion, and outline the scope of their involvement over the course of the project. Refer to the engagement resources page on the PCORI website (www.pcori.org). |

Based on PCORI research plan template (https://www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/announcement/broad-pcori-funding-announcements-cycle-1-2020. PCORI methodology standards can be found at: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards. QM-1=qualitative approach to research inquiry, design, and conduct; QM-2=select and justify appropriate qualitative methods sampling strategy; QM-3=link the qualitative data analysis, interpretation, and conclusions to the study question; QM-4=establish trustworthiness and credibility of qualitative research; MM-1=specify how mixed methods are integrated across design, data sources, and data/or collection phases; MM-2=select and justify appropriate mixed methods sampling strategy; MM-3=integrate data analysis, data interpretation, and conclusions.

QM-1: State the qualitative approach to research inquiry, design, and conduct

Many research proposals on patient centered outcomes research or comparative effectiveness research propose the use of qualitative methods but lack adequate description of and justification for the qualitative approach that will be used. Often the rationale for using qualitative methods is not tied back to the applicable literature and the identified evidence gap, missing the opportunity to link the importance of the approach in capturing the human experience or patient voice in the research aims. The approach to inquiry should be explicitly stated along with the rationale and a description of how it ties to the research question(s). The research proposal should clearly define how the qualitative approach will be operationalized and supports the choice of methods for participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis. Moreover, procedures for data collection should be stated, as well as the types of data to be collected, when data will be collected (that is, one point in time v longitudinal), data management, codebook development, intercoder reliability process, data analysis, and procedures for ensuring full confidentiality.

QM-2: Select and justify appropriate qualitative methods and sampling strategy

While the number of participants who will be recruited for focus groups or in-depth interviews is usually described, the actual sampling strategy is often not stated. The description of the sampling strategy should state how it aligns with the qualitative approach, how it relates to the research question(s), and the variation in sampling that might occur over the course of the study. Furthermore, most research proposals state that data will be collected until thematic saturation is reached, but how this will be determined is omitted. As such, this standard outlines the information essential for understanding who is participating in the study and aims to reduce the likelihood of making unsupported statements, emphasizing transparency in the criteria used to determine the stopping point for recruitment and data collection.

QM-3: Link the qualitative data analysis, interpretations, and conclusions to the study question

Qualitative analysis transforms data into information that can be used by the relevant stakeholder. It is a process of reviewing, synthesizing, and interpreting data to describe and explain the phenomena being studied. The interpretive process occurs at many points in the research process. It begins with making sense of what is heard and observed during data gathering, and then builds understanding of the meaning of the data through data analysis. This is followed by development of a description of the findings that makes sense of the data, in which the researcher’s interpretation of the findings is embedded. Many research proposals state that the data will be coded, but it is unclear by whom, their qualifications, or the process. Very little, if any, description is provided as to how conclusions will be drawn and how they will be related to the original data, and this standard highlights the need for detailed information on the analytical and interpretive processes for qualitative data and its relationship to the overall study.

QM-4: Establish trustworthiness and credibility of qualitative research

The qualitative research design should incorporate elements demonstrating validity and reliability, which are also known by terms such as trustworthiness and credibility. Studies with qualitative components can use several approaches to help ensure the validity and reliability of their findings, including audit trail, reflexivity, negative or deviant case analysis, triangulation, or member checking (see table 1 for definitions).

MM-1: Specify how mixed methods are integrated across design, data sources, and/or data collection phases

This standard requires investigators to declare and support their intent to conduct a mixed methods approach a priori in order to avoid a haphazard approach to the design and resulting data. Use of mixed methods can enhance the study design, by using the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative research as investigators are afforded the use of multiple data collection tools rather than being restricted to one approach. Mixed methods research designs have three key factors: integration of data, relative timing, and implications of linkages for methods in each component. Additionally, the standards for mixed methods, quantitative, and qualitative methodologies must be met in the design, implementation, and reporting stages. This is different from a multimethod research design in which two or more forms of data (qualitative, quantitative, or both) are used to resolve different aspects of the research question independently and are not integrated.

MM-2: Select and justify appropriate mixed methods sampling strategy

Mixed methods research aims to contribute insights and knowledge beyond that obtained from quantitative or qualitative methods only, which should be reflected in the sampling strategies as well as in the design of the study and the research plan. Qualitative and quantitative components can occur simultaneously or sequentially, and researchers must select and justify the most appropriate mixed method sampling strategy and demonstrate that the desired number and type of participants can be achieved with respect to the available time, cost, research team skillset, and resources. Those sampling strategies that are unique to mixed methods (eg, interdependent, independent, and combined) should focus on the depth and breadth of information across research components.

MM-3: Integrate data analysis, data interpretations, and conclusions

Qualitative and quantitative data often are analyzed in isolation, with little thought given to when these analyses should occur or how the analysis, interpretation, and conclusions integrate with one another. There are multiple approaches to integration in the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data (eg, merging, embedding, and connecting). As such, the approach to integration should determine the priority of the qualitative and quantitative components, as well as the temporality with which analysis will take place (eg, sequentially, or concurrently; iterative or otherwise). Either a priori or emergently, where appropriate, researchers should define these characteristics, identify the points of integration, and explain how integrated analyses will proceed with respect to the two components and the selected approach.

Summary

The choice between multiple options for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of health conditions presents a considerable challenge to patients, clinicians, and policy makers as they seek to make informed decisions. Patient centered outcomes research focuses on the pragmatic comparison of two or more health interventions to determine what works best for which patients and populations in which settings.5 The use of qualitative and mixed methods research can enable more robust capture and understanding of information from patients, caregivers, clinicians, and other stakeholders in research, thereby improving the strength, quality, and relevance of findings.4

Despite extensive literature on qualitative and mixed methods research in general, the use of these methodologies in the context of patient centered outcomes research or comparative effectiveness research continues to grow and requires additional guidance. This guidance could facilitate the appropriate design, conduct, analysis, and reporting of these approaches. For example, the need for including multiple stakeholder perspectives, understanding how an intervention was implemented across multiple settings, or documenting the clinical context so decision makers can evaluate whether findings would be transferable to their respective settings pose unique challenges to the rigor and agility of qualitative and mixed methods approaches.

PCORI’s methodology standards for qualitative and mixed methods research represent an opportunity for further strengthening the design, conduct, and reporting of patient centered outcomes research or comparative effectiveness research by providing guidance that encompasses the broad range of methods that stem from various philosophical assumptions, disciplines, and procedures. These standards directly affect factors related to methodological integrity, accuracy, and clarity as identified by PCORI staff, methodology committee members, and merit reviewers in studies on patient centered outcomes research or comparative effectiveness research. The standards are presented at a level accessible to researchers new to qualitative and mixed methods research; however, they are not a substitute for appropriate expertise.

The challenges of ensuring rigorous methodology in the design and conduct of research are not unique to qualitative and mixed methods research, because the imperative to increase value and reduce waste in research design, conduct, and analysis is widely recognized.36 Consistent with such efforts, PCORI recognizes the importance of continued methodological development and evaluation and is committed to listening to the research community and providing updated guidance based on methodological advances and research needs.37

Acknowledgments

We thank the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) methodology committee during this work (Naomi Aronson, Ethan Bach, Stephanie Chang, David Flum, Cynthia Girman, Steven Goodman (chairperson), Mark Helfand, Michael S Lauer, David O Meltzer, Brian S Mittman, Sally C Morton, Robin Newhouse (vice chairperson), Neil R Powe, and Adam Wilcox); and Frances K Barg, Benjamin F Crabtree, Deborah Cohen, Michael Fetters, Suzanne Heurtin-Roberts, Deborah K Padgett, Janice Morse, Lawrence A Palinkas, Vicki L Plano Clark, and Catherine Pope, for participating in the expert panel meeting and consultation.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary material

Contributors: BG led the development of the methodology standards and wrote the first draft of the paper. MH, AB, SZ, EE, DH, and RN made a substantial contribution to all stages of developing the methodology standards. BG, SZ, MH, and AB drafted the methodology standards. DH, EE, and RN gave critical insights into PCORI’s methodology standards development processes and guidance. SZ served as qualitative methods consultant to the workgroup. BG provided project leadership and guidance. MH and AB facilitated the expert panel meeting. SZ is senior author. BG and SZ are the guarantors of this work and accept full responsibility for the finished article and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: No funding was used to support this work. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its board of governors or methodology committee. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/conflicts-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the work being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the work as planned have been explained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and stakeholders were invited to comment on the draft standards during the public comment period held from 24 July 2018 to 21 September 2018. Comments were reviewed and revisions made accordingly. Development of the standards, including the methods, were presented at two PCORI board of governors’ meetings, which are open to the public, recorded, and posted on the PCORI website.

References

- 1. Collins CS, Stockton CM. The central role of theory in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 2018;17:1-10 10.1177/1609406918797475 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications, Inc, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013;48:2134-56. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Patient-centered outcomes research. 2010-19. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-we-support.

- 5. Institute of Medicine Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research. National Academies Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed Sage Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice 2000;39:124-30 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001;358:483-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res 1999;34:1189-208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed Sage Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 4th ed Sage Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Clegg Smith KC, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Best practices for mixed methods research in health sciences. National Institutes of Health, 2011. 10.1037/e566732013-001 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148 Stat. 119 (March 23, 2010).

- 14.Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-94 (20 December 2019).

- 15.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI methodology standards. 2011-19. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards.

- 16. Fetters MD, Molina-Azorin JF. The Journal of Mixed Methods Research starts a new decade: the mixed methods research integration trilogy and its dimensions. J Mixed Methods Res 2017;11:291-307 10.1177/1558689817714066 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aspers P, Corte U. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual Sociol 2019;42:139-60. 10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chapple A, Rogers A. Explicit guidelines for qualitative research: a step in the right direction, a defence of the ‘soft’ option, or a form of sociological imperialism? Fam Pract 1998;15:556-61. 10.1093/fampra/15.6.556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G. Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res 1998;8:341-51. 10.1177/104973239800800305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Treloar C, Champness S, Simpson PL, Higginbotham N. Critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research studies. Indian J Pediatr 2000;67:347-51. 10.1007/BF02820685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cesario S, Morin K, Santa-Donato A. Evaluating the level of evidence of qualitative research. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2002;31:708-14. 10.1177/0884217502239216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349-57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, SQUIRE development group Publication guidelines for quality improvement studies in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. BMJ 2009;338:a3152. 10.1136/bmj.a3152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:529-46. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute. Qualitative methods in implementation science. 2018. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/nci-dccps-implementationscience-whitepaper.pdf

- 27. Burns N. Standards for qualitative research. Nurs Sci Q 1989;2:44-52. 10.1177/089431848900200112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245-51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The guidelines manual. Appendix H: Methodology checklist: qualitative studies. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/resources/the-guidelines-manual-appendices-bi-2549703709/chapter/appendix-h-methodology-checklist-qualitative-studies.

- 30. Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:331-9. 10.1370/afm.818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res 2007;1:112-33 10.1177/1558689806298224 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. American Psychological Association Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. 7th ed American Psychological Association, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, Frost DM, Josselson R, Suárez-Orozco C. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: the APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am Psychol 2018;73:26-46. 10.1037/amp0000151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levitt HM, Motulsky SL, Wertz FJ, Morrow SL, Ponterotto JG. Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology: Promoting methodological integrity. Qual Psychol 2017;4:2-22 10.1037/qup0000082 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shaw RL, Bishop FL, Horwood J, Chilcot J, Arden MA. Enhancing the quality and transparency of qualitative research methods in health psychology. Br J Health Psychol 2019;24:739-45. 10.1111/bjhp.12393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet 2014;383:166-75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The PCORI methodology report. 2019. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Methodology-Report.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material