According to past analyses of prescription and treatment patterns for major depressive disorder (MDD), the majority of MDD patients in Japan have not been treated according to the recommended guidelines. 1 In this context, the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders published the ‘Treatment Guidelines for Major Depressive Disorders’ (GL) in 2012, and the ‘Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE)’ project was launched in 2016, which aimed to standardize medical practice using quality indicators (QI) as indices for the quality of medical practice. 2 , 3

The present study was a cross‐sectional, retrospective study conducted in a total of 84 institutions (36 university hospitals, 23 national/public hospitals, and 25 private hospitals). According to the recommendations of the GL, a total of eight QI (Table S1) were evaluated based on the survey of the treatments and prescriptions at discharge for patients with MDD during the first year (2016–2018) in the participating hospitals. The data were collected by the EGUIDE project members. In this survey, we recorded all types and dosages of psychotropic drugs, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and benzodiazepines. The use of modified electroconvulsive therapy (mECT) and cognitive behavioral therapy were also recorded. The ethics committees of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and each participating university/hospital/clinic approved the entire study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants (psychiatrists who treated the inpatients). The treated inpatients could see the purpose and procedures of the study on websites and could refuse to participate freely (opt‐out).

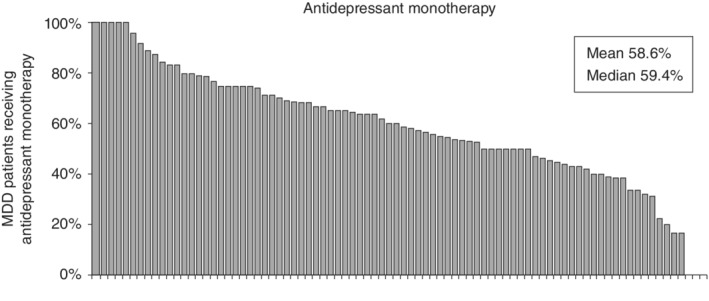

This survey involved a sample of 1283 patients who had been diagnosed with MDD at discharge (Table S2). Values of each QI in all subjects and in each hospital are presented in Table S3. In this study, only 60.2% of patients received antidepressant monotherapy, with a large institutional difference from less than 20% to 100% (Fig. 1). A previous report already confirmed that antidepressant polypharmacy prevailed in Japan, 1 while this is the first report showing a large institutional difference. The proportion of patients who received no prescription of anxiolytics or hypnotics was only 25.1%, which is consistent with the study showing long‐term benzodiazepine use despite the recent clinical guidelines in Japan. 4 Although combination therapy with antidepressants and benzodiazepines may be more effective than therapy with antidepressants alone in the early phase, these effects may not be maintained in the acute or continuous phase. 5 Thus, long‐term benzodiazepine use is not recommended in the GL due to the potential side‐effects. The QI values for each hospital type are presented in Table S4. QI‐1 was significantly higher in university hospitals than in national/public hospitals, while QI‐3, QI‐4, QI‐5, and QI‐6 were significantly higher in university hospitals than in private hospitals. Possible explanations for institutional differences include different instructions from senior psychiatrists regarding prescribing and treatment. Many psychiatry residents included in this study were affiliated with university hospitals and they generally follow the GL rather than prescribing traditions introduced by senior psychiatrists. As regional differences in treatment patterns have been previously reported, 6 , 7 comparisons of QI values between eastern and western Japan are shown in Table S5. There was a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving mECT in eastern Japan (17.6%) compared to that in western Japan (8.4%). Although a compositional difference in hospital type between eastern and western Japan (university: 46.9% vs 37.1%; national/public: 34.7% vs 17.1%; private 18.4% vs 45.7%; χ2‐test P = 0.019) may affect the difference, the difference in the proportion of patients undergoing mECT may stem from different attitudes towards mECT in these regions. The low proportion of patients undergoing mECT treatment in private hospitals (3%) may be because most private hospitals do not have the facilities for mECT. The low proportion of patients undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy in all hospitals (1%) may reflect the low level of provision of cognitive behavioral therapy despite its coverage by Japanese health insurance. 7

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) receiving antidepressant monotherapy (quality indicator‐1) in 84 hospitals. There is a large difference in the proportion of patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy among the hospitals, ranging from less than 20% to 100%.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not assess depressive symptoms using rating scales. Second, this study may have a selection bias because these 84 hospitals may not reflect the treatment and prescription patterns of all hospitals in Japan. The ratio of antidepressant monotherapy may be affected by not only hospital type but also the patient's background, such as refractory episodes, and the difference in positioning and role of the hospital in the community.

In accordance with the GL, we should strive to reduce antidepressant polypharmacy and long‐term use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of MDD in Japan. Based on this baseline survey, we plan to report changes brought by the GL education program. In the future, proper diagnosis and treatment following dissemination of and adherence to the GL will provide suitable circumstances for high‐quality research of MDD. 8 , 9 , 10

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Supporting information

Table S1 The eight quality indicators (QI) used in the present study.

Table S2 Demographic data of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Table S3 Quality indicator (QI) values for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) in the first year of participation. The QI of each patient (n = 1283) is presented. The QI for each hospital (n = 84) was also calculated and is presented as the mean ± SD and the median with interquartile range (IQR).

Table S4 Quality indicator (QI) values for each hospital type in the first year of participation. The QI of five subgroups of the 84 hospitals divided by hospital type (university hospital, national/public hospitals, and private hospitals) are presented as the means ± SD. QI values in each group were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the post‐hoc test (Dunn test). The significance level was set at two‐tailed P < 6.25 × 10−3 because the Bonferroni method was applied. The significance level of the post‐hoc test was set at P < 1.7 × 10−2. Significant P‐values are boldfaced and underlined.

Table S5 Quality indicator (QI) values of eastern Japan and western Japan in the first year of participation. The QI of five subgroups of the 84 hospitals divided by region (eastern Japan, western Japan) are presented as the means ± SD. QI values in each group were compared with the Mann–Whitney U‐test. The significance level was set at two‐tailed P < 6.25 × 10−3 as the Bonferroni method was applied. Significant P‐values are boldfaced and underlined. There was a significant compositional difference in hospital type between eastern and western Japan (university: 46.9% vs 37.1%; national/public: 34.7% vs 17.1%; private: 18.4% vs 45.7%; χ2‐test P = 0.019.

References

- 1. Onishi Y, Hinotsu S, Furukawa TA, Kawakami K. Psychotropic prescription patterns among patients diagnosed with depressive disorder based on claims database in Japan. Clin. Drug Investig. 2013; 33: 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ichihashi K, Hori H, Hasegawa N et al Prescription patterns in patients with schizophrenia in Japan: First‐quality indicator data from the survey of “Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE)” project. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2020; 40: 281–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takaesu Y, Watanabe K, Numata S et al Improvement of psychiatrists’ clinical knowledge of the treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorders using the ‘Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE)’ project: A nationwide dissemination, education, and evaluation study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019; 73: 642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takano A, Ono S, Yamana H et al Factors associated with long‐term prescription of benzodiazepine: A retrospective cohort study using a health insurance database in Japan. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e029641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y et al Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for adults with major depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019; 6: CD001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okumura M, Sameshima T, Awata S et al The present state of electroconvulsive therapy in Japan. Jpn. J. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010; 22: 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayashi Y, Yoshinaga N, Sasaki Y et al How was cognitive behavioural therapy for mood disorder implemented in Japan? A retrospective observational study using the nationwide claims database from FY2010 to FY2015. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e033365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inoue T, Sasai K, Kitagawa T, Nishimura A, Inada I. Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of vortioxetine in Japanese patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020; 74: 140–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akechi T, Kato T, Fujise N et al Why some depressive patients perform suicidal acts and others do not. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019; 73: 660–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sado M, Wada M, Ninomiya A et al Does the rapid response of an antidepressant contribute to better cost‐effectiveness? Comparison between mirtazapine and SSRIs for first‐line treatment of depression in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019; 73: 400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 The eight quality indicators (QI) used in the present study.

Table S2 Demographic data of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Table S3 Quality indicator (QI) values for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) in the first year of participation. The QI of each patient (n = 1283) is presented. The QI for each hospital (n = 84) was also calculated and is presented as the mean ± SD and the median with interquartile range (IQR).

Table S4 Quality indicator (QI) values for each hospital type in the first year of participation. The QI of five subgroups of the 84 hospitals divided by hospital type (university hospital, national/public hospitals, and private hospitals) are presented as the means ± SD. QI values in each group were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the post‐hoc test (Dunn test). The significance level was set at two‐tailed P < 6.25 × 10−3 because the Bonferroni method was applied. The significance level of the post‐hoc test was set at P < 1.7 × 10−2. Significant P‐values are boldfaced and underlined.

Table S5 Quality indicator (QI) values of eastern Japan and western Japan in the first year of participation. The QI of five subgroups of the 84 hospitals divided by region (eastern Japan, western Japan) are presented as the means ± SD. QI values in each group were compared with the Mann–Whitney U‐test. The significance level was set at two‐tailed P < 6.25 × 10−3 as the Bonferroni method was applied. Significant P‐values are boldfaced and underlined. There was a significant compositional difference in hospital type between eastern and western Japan (university: 46.9% vs 37.1%; national/public: 34.7% vs 17.1%; private: 18.4% vs 45.7%; χ2‐test P = 0.019.