Abstract

Aims

We sought to determine sex‐based differences in biomarkers, self‐reported health status, and magnitude of longitudinal changes in measures of reverse cardiac remodelling among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%) treated with sacubitril/valsartan (S/V).

Methods and results

This was a subgroup analysis of patients initiated on S/V in the Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement and Ventricular Remodeling During Entresto Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE‐HF) study. There were 226 (28.5%) women in the study. Though women had lower baseline N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), they had more rapid early reduction in the biomarker after initiation of S/V. Compared to men, women had lower average baseline Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)‐23 Total Symptom score (67.6 vs. 71.9; P = 0.003) but showed greater linear improvement (7.4 vs. 5.5 points; P < 0.001) and faster pace of KCCQ change (P < 0.001) over the course of the trial. Women and men demonstrated similar degrees of reverse left ventricular remodelling following S/V initiation; however, women did so earlier than men with more consistent changes. These results remained unchanged with adjustment for relevant covariates. Reduction in NT‐proBNP was associated with reverse cardiac remodelling in both women and men. Treatment with S/V was well tolerated in all.

Conclusions

In women with HFrEF, treatment with S/V was associated with significant NT‐proBNP reduction, health status improvement and reverse cardiac remodelling.

Keywords: Heart failure, Biomarkers, Remodelling, Sacubitril/valsartan

A summary of differences between women and men in the PROVE‐HF study.

Introduction

Substantial differences exist in the epidemiology, progression, and outcomes of cardiovascular disease in women vs. men. This includes significant sex‐based differences in those with heart failure (HF); women tend to have higher indexed left ventricular (LV) wall thicknesses and worse diastolic function compared to men. 1 Among those with HF and reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF; LV ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%], women tend to clinically present with more significant symptoms, especially those with an ischaemic aetiology of HF. 2 Outcomes in women with HFrEF may also differ from men.

Unfortunately, women tend to be disproportionately underrepresented in clinical trials for HFrEF therapies, posing a substantial challenge to investigating sex‐based differences in responses to favourable treatments for HFrEF. What limited data do exist suggest women generally experience more favourable changes in measures of cardiac reverse remodelling than men following drug and device therapy for HF, 3 , 4 with more improved LVEF, lower LV mass and volume, and markedly attenuated activation of natriuretic peptides. 3 Thus, therapies with favourable effects on measures of cardiac reverse remodelling 5 may exert differential benefits in women with HFrEF, however this has not been previously investigated at a large scale.

Sacubitril/valsartan (S/V), a combined angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), is among the newest guideline‐supported options for treatment of HFrEF 6 reducing risk in patients affected by chronic HFrEF. 7 Most recently, the Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement and Ventricular Remodeling During Entresto Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE‐HF; NCT02887183) study 8 suggested that S/V had favourable effects on measures of cardiac remodelling in patients with chronic HFrEF. Longitudinal changes in measures of cardiac reverse remodelling were also strongly associated with simultaneous reductions in N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) concentrations. Whether sex‐based differences existed in responses to treatment with S/V remains unknown despite guideline recommendations for its use in chronic HFrEF.

In this post hoc analysis of patients with HFrEF enrolled in the PROVE‐HF study, we evaluated sex‐based differences in biomarkers, health status, and remodelling parameters after treatment with S/V.

Methods

All study procedures were approved by each center's Institutional Review Board and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

PROVE‐HF study design and participants

The design of PROVE‐HF has been detailed previously. 9 Briefly, this was a 52‐week, multicentre, open‐label, single‐arm study that enrolled 794 patients with chronic HFrEF who were then initiated and titrated on S/V per United States prescribing information. 8 , 9 Whenever possible, the dose of S/V was titrated to the target dose of 97/103 mg twice daily. After informed consent was obtained, detailed clinical and historical variables were recorded using a standardized case report form. New‐onset HF was defined as diagnosis <60 days from study enrolment. Echocardiographic assessments of LVEF, LV mass, LV volume, and diastolic function were performed at baseline and 6 and 12 months and were read by temporally‐blinded readers at a core laboratory after study procedures had completed. Cardiac reverse remodelling was defined by changes in LVEF, LV end‐diastolic volume index (LVEDVi; normal <76 mL/m2), and LV end‐systolic volume index (LVESVi; normal <30 mL/m2) after S/V initiation. 8

Blood samples were collected from participants at each study visit and sent to a central laboratory for measurement of plasma NT‐proBNP using a commercially available electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (proBNP II, Roche Diagnostics).

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)‐23 was used to collect self‐reported health status and health‐related quality of life (HRQoL); participant responses are scaled into multiple summary scores including the Total Symptom (TS) score, Clinical Summary (CS) score, and Overall Summary (OS) score. The KCCQ‐23 was administered to study participants at baseline, day 14, and months 1, 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12. 9 All adverse events and serious adverse events were recorded; suspected cases of angioedema were evaluated by a central adjudication panel. 8

Present analysis

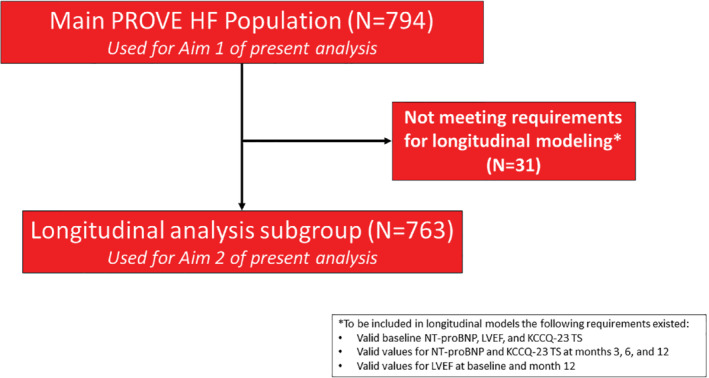

This study was a post hoc analysis of data collected from PROVE‐HF participants with comparisons between the women and men in the study. A study flow diagram is detailed in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Study flow for the present analysis. We sought to characterize baseline and cross‐sectional values as well as longitudinal aspects of change in N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), health status, and cardiac remodelling parameters. KCCQ‐23 TS, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire‐23 Total Symptom score; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

There were two aims to the present study:

Aim 1: To determine the magnitude of sex‐based differences, if any, in patient characteristics and compare values for NT‐proBNP, measures of health status (KCCQ‐23 TS score) and values of cardiac reverse remodelling (i.e. LVEF, LVEDVi, LVESVi) across time points.

Aim 2: To determine whether women and men shared similar trajectories of longitudinal changes in NT‐proBNP, LVEF, and KCCQ‐23 TS score.

For our first study aim, we maximized the use of available data from all cases (n = 794) and report characteristics and values using pairwise deletion. Patient demographics, clinical biomarkers, and echocardiogram data were summarized using scale‐appropriate measures for categorical variables (e.g. counts, percentages) and interval variables [e.g. means ± standard deviations, medians (25th–75th percentile)]. Given the post hoc, non‐prespecified nature of the comparisons, we used Hedge's g to estimate the magnitude of standardized mean differences between sexes rather than chi‐squared or t‐tests; within‐group (paired) differences were estimated using a bias‐adjusted standardizer (δ). The Phi coefficient (rφ) was used to evaluate symmetry in distributions of categorical variables; the Phi coefficient is analogous to a standardized mean difference for interval‐scaled variables. 10

For our second aim, we examined longitudinal associations between sex, NT‐proBNP, LVEF, and KCCQ‐23 TS score were examined using latent growth curve models (LGCMs), similar to other studies 11 , 12 , 13 ; these analyses allow for understanding not only the magnitude and speed of change in serially measured variables, but also inter‐relatedness with potentially associated factors (e.g. NT‐proBNP change and LVEF improvement). The LGCMs were adjusted for ischaemic aetiology, LVEF, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) presence and use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEi/ARB) at baseline. Log‐transformed values for NT‐proBNP were used in all inferential procedures. Associations between covariates were assessed using Pearson correlations (r). To minimize residual variance, for Aim 2, we placed restrictions on the extent of allowable missing data; for these analyses, we included cases with (i) valid baseline value for NT‐proBNP, LVEF, and KCCQ‐23 TS score; (ii) valid values for NT‐proBNP and KCCQ‐23 for month 3, month 6, and month 12; and (iii) valid values for LVEF at baseline and month 12. After implementing restrictions on missing data, 763 patients were included in the second component of our analysis. We used the KCCQ TS score due to multicollinearity with the CS and OS scores; additionally, the TS score is the most proximal to individual metrics and, therefore, represents patient self‐report more directly. Probability thresholds for statistical significance were set at 0.05 using two‐sided tests and standard errors were calculated with bootstrapping using 99% confidence intervals and 1000 subsamples. All analyses were conducted using R v3.5.

Results

Aim 1: characterizing sex‐based differences in baseline and follow‐up variables

Baseline characteristics by participant sex are detailed in Table 1 . Briefly, 226 (28.5%) of the 794 patients enrolled in PROVE‐HF were women. Moderate‐sized differences were observed for HF aetiology with women more likely to have a non‐ischaemic HF aetiology than men (61.5% vs. 40.3%). Small‐to‐moderate‐sized differences were observed regarding use HF therapies at baseline; women were less likely to receive ACEi/ARB (71.7% vs. 77.5%) or prior CRT and implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator placement (8.8% vs. 18.0%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics in men and women enrolled in PROVE‐HF with standardized mean differences (g or rφ)

| Parameter | All patients (n = 794) | Women (n = 226) | Men (n = 568) | Standardized mean differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g or rφ | Category | ||||

| Age, years, median | 66 (57–74) | 65 (57–74) | 66 (58–74) | 0.06 | Small |

| NYHA class symptom severity, n (%) | 0.17 | Small | |||

| II | 558 (70.3) | 165 (73) | 393 (69.2) | ||

| III | 222 (28) | 60 (26.5) | 162 (28.5) | ||

| IV | 14 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 13 (2.3) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median | 30.5 (26.5–35.3) | 30.1 (25.9–36.8) | 30.6 (26.6–34.7) | 0.005 | Small |

| Past medical history, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 699 (88) | 196 (86.7) | 503 (88.6) | 0.11 | Small |

| Coronary revascularization | 376 (47.4) | 68 (30.1) | 308 (54.2) | 0.27 | Small‐moderate |

| Diabetes mellitus | 361 (45.5) | 97 (42.9) | 264 (46.5) | 0.07 | Small |

| Myocardial infarction | 329 (41.4) | 67 (29.6) | 262 (46.1) | 0.35 | Small‐moderate |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 280 (35.3) | 69 (30.5) | 211 (37.1) | 0.14 | Small |

| Ischaemic aetiology for HF, n (%) | 426 (53.7) | 87 (38.5) | 339 (59.7) | 0.43 | Moderate |

| Time since HF diagnosis, months, median (25th–75th) | 50.5 (15.0–109.6) | 51.8 (13.3–112.1) | 50.4 (16.7–106.7) | 0.003 | Small |

| New‐onset HF (<60 days before enrolment), n (%) | 78 (9.8) | 30 (13.3) | 48 (8.5) | 0.16 | Very small |

| Guideline‐directed therapy, n (%) | |||||

| Beta‐blocker | 766 (96.5) | 218 (96.5) | 548 (96.5) | 0.001 | Small |

| ACEi/ARB | 602 (75.8) | 162 (71.7) | 440 (77.5) | 0.21 | Small‐moderate |

| MRA | 336 (42.3) | 98 (43.4) | 238 (41.9) | 0.03 | Small |

| CRT/CRT‐D | 122 (15.4) | 20 (8.8) | 102 (18) | 0.21 | Small‐moderate |

| ICD alone | 226 (28.5) | 56 (24.8) | 170 (29.9) | 0.08 | Small |

| Not taking ACEi/ARB, n (%) | 0.21 | Small‐moderate | |||

| ACEi/ARB naïve (never exposed) | 48 (6) | 22 (9.7) | 26 (4.6) | ||

| Previously taking but not currently | 144 (18.1) | 42 (18.6) | 102 (18) | ||

| Baseline laboratory results | |||||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, median | 62.6 (50.1–75.7) | 60.75 (46.1–74.5) | 63.3 (51.1–76.3) | 0.18 | Small |

| eGFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 353 (44.5) | 110 (48.7) | 243 (42.8) | 0.31 | Small‐moderate |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL, median (25th–75th) | 816 (332–1821) | 659 (278–1735.5) | 863 (380–1866) | 0.02 | Small |

| Baseline vital signs | |||||

| Systolic BP, mmHg, median | 122 (113–134) | 122 (112–134) | 123 (114–134) | 0.06 | Small |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg, median | 76 (69–82) | 74 (68–81) | 76 (70–82) | 0.13 | Small |

| Heart rate, bpm, median | 71 (64–80) | 72 (66–80.8) | 70 (64–79) | 0.21 | Small‐moderate |

| Baseline echo measurements, median (25th–75th) | |||||

| LVEF, % | 28.3 (24.5–32.7) | 30.4 (25.9–33.9) | 27.5 (24.2–32.2) | 0.34 | Small‐moderate |

| LVEDVi, mL/m2 | 86.9 (76.2–100.4) | 81.7 (71.8–95.1) | 89.3 (77.8–101.8) | 0.41 | Moderate |

| LVESVi, mL/m2 | 61.7 (52.0–74.8) | 56.4 (48.5–68.7) | 63.5 (53.6–77.03) | 0.42 | Moderate |

| LAVi, mL/m2 | 37.7 (31.6–46.1) | 35.5 (30.8–44.2) | 38.7 (31.8–46.5) | 0.16 | Small |

| E/E′ | 11.7 (8.8–16) | 12.9 (9.8–16.6) | 11.1 (8.3–15.6) | 0.18 | Small |

| Baseline KCCQ, median (25th–75th) | |||||

| Overall score | 64.6 (46.9–81.2) | 59.6 (41.9–78.6) | 65.9 (47.7–81.8) | 0.18 | Small |

| Clinical Summary score | 69.8 (52–85.8) | 65.2 (45.8–82.8) | 71.4 (53.1–87) | 0.24 | Small‐moderate |

| Total Symptom score | 75.0 (53.1–87.5) | 72.9 (47.9–85.4) | 75.0 (54.7–87.5) | 0.17 | Small |

ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CRT‐D, cardiac resynchronization therapy‐defibrillator; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LAVi, left atrial volume index; LVEDVi, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

At baseline, there were negligible differences in NT‐proBNP concentrations between sexes. In contrast, women had moderately lower baseline values than men for LVEDVi (81.7 mL/m2 vs. 89.3 mL/m2) and LVESVi (56.4 mL/m2 vs. 63.5 mL/m2) with correspondingly higher baseline values for LVEF (30.4% vs. 27.5%). Small‐sized differences were observed for left atrial volume index and E/e′. Negligible differences were observed in the rate of participants who achieved the target dose of 97/103 mg twice daily (67.0% men; 57.8% women).

Cross‐sectional concentrations of NT‐proBNP in women and men from baseline to 12 months are detailed in Table 2 . In both women and men, greatest decreases in NT‐proBNP were seen by 14 days following S/V initiation. Within‐group differences between time points showed that men had greater decreases in NT‐proBNP from baseline to month 3 than women; however, across 12 months of follow‐up, women had more consistent NT‐proBNP reduction (online supplementary Table S1 ).

Table 2.

Median (25th–75th percentile) N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide concentrations across time points in the study as a function of sex

| Time point | Women | n | Men | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 659 (282–1741) | 217 | 863 (383–1886) | 546 |

| Day 14 | 485 (176–1262) | 213 | 537 (267–1378) | 535 |

| Day 30 | 468 (164–1285.75) | 210 | 572.5 (222–1319) | 528 |

| Day 45 | 484 (151–1303) | 204 | 526 (228–1250) | 523 |

| Month 2 | 480 (159–1271) | 200 | 552 (239–1294) | 517 |

| Month 3 | 467 (162–1414) | 202 | 496 (245–1265) | 515 |

| Month 6 | 437 (161–1185) | 192 | 469 (181–1089) | 494 |

| Month 9 | 391 (140–1023) | 186 | 456 (191–1186) | 463 |

| Month 12 | 429 (132–1185) | 193 | 529 (173–1264) | 496 |

Cross‐sectional results for the KCCQ‐23 TS score are detailed in Table 3 . Following initiation of S/V, women had larger early gains in KCCQ‐23 TS scores from baseline to month 3; paired differences at subsequent time points were small or negligible for both sexes (online supplementary Table S1 ).

Table 3.

Median (25th–75th percentile) Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire‐23 Total Summary score across time points in the study as a function of sex

| Time point | Women | n | Men | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 75.0 (54.7–87.5) | 530 | 72.9 (47.9–85.4) | 210 |

| Day 14 | 79.2 (62.5–95.8) | 517 | 77.6 (64.6–89.6) | 204 |

| Day 30 | 83.3 (63.5–96.9) | 513 | 77.6 (61.5–91.7) | 206 |

| Month 2 | 85.4 (67.7–97.9) | 480 | 81.2 (66.7–95.6) | 186 |

| Month 3 | 85.4 (66.7–96.9) | 493 | 81.2 (66.7–91.7) | 197 |

| Month 6 | 85.4 (66.95–97.9) | 486 | 83.3 (68.8–93.8) | 187 |

| Month 9 | 85.4 (69.8–97.9) | 450 | 82.3 (64–93.8) | 179 |

| Month 12 | 86.5 (66.7–97.9) | 481 | 83.3 (62.5–94.3) | 189 |

Values of LVEF, LVEDVi and LVESVi at each time point are detailed in Table 4 and online supplementary Figure S1 . Overall, women and men demonstrated comparable reverse cardiac remodelling after S/V treatment. Similarly, though NT‐proBNP values differed between women and men, they had similar correlation between change in NT‐proBNP and reverse remodelling. Notably, women tended to reverse remodel earlier, with average changes in LVEF, LVESVi, and LVEDVi larger in women from baseline to month 6 (online supplementary Table S1 ). Conversely, changes in these measures from month 6 to month 12 were generally larger among men.

Table 4.

Measures of cardiac remodelling among patients across time points in the study as a function of sex

| Measures | Women (n = 226) | Men (n = 568) |

|---|---|---|

| LVEF | ||

| Baseline | 30.4 (25.9–33.9) | 27.5 (24.1–32.2) |

| Month 6 | 36.1 (30.7–41.5) | 33.3 (27.5–38.2) |

| Month 12 | 40.1 (33.4–47.5) | 36.8 (31.7–44.2) |

| LVEDVi | ||

| Baseline | 82.2 (72.5–95.6) | 89.7 (77.7–101.9) |

| Month 6 | 73.6 (63.1–89.6) | 81.8 (72.0–94.6) |

| Month 12 | 68.8 (57.4–83.4) | 75.5 (65.3–87.9) |

| LVESVi | ||

| Baseline | 56.5 (48.7–69.0) | 63.5 (53.6–77.2) |

| Month 6 | 46.4 (37.3–60.3) | 53.6 (45.1–68.9) |

| Month 12 | 40.9 (30.4–54.1) | 46.8 (37.1–59.6) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDVi, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVESVi, left ventricular end‐systolic volume index.

Among women, higher baseline NT‐proBNP concentrations correlated with lower baseline LVEF (r = −0.55); baseline NT‐proBNP and LVEF had trivial correlations with baseline KCCQ‐23 TS scores (r < 0.10). Among men, higher baseline NT‐proBNP concentrations similarly correlated with lower baseline LVEF (r = −0.45); baseline NT‐proBNP and LVEF values correlated weakly with baseline KCCQ‐23 TS scores (r = −0.12, r = 0.14, respectively).

Aim 2: longitudinal analyses

Among women, baseline values for NT‐proBNP and LVEF were weakly correlated with the subsequent change for each measure (online supplementary Table S1 and Figure S2 ), suggesting the extent of change was unrelated to baseline values. In contrast, after initiation of S/V, the magnitude and speed of change in NT‐proBNP concentrations were more substantially correlated to changes in LVEF (linear: r = −0.70; quadratic: r = 0.43).

Men experienced similar changes in NT‐proBNP concentrations, LVEF, and KCCQ‐23 TS scores over the course of the PROVE‐HF study (online supplementary Table S1 and Figure S2 ). Similar to women, baseline values and the extent of change in NT‐proBNP were weakly correlated (r = 0.19), but unlike in women, baseline values for LVEF were moderately correlated to its subsequent change (r = 0.42). Despite this fact, changes in NT‐proBNP concentrations after S/V initiation were still correlated to changes in LVEF (linear: r = −0.46; quadratic: r = 0.33).

With adjustment for ischaemic aetiology, LVEF, CRT presence and use of ACEi/ARB at baseline, rates of NT‐proBNP change were not significant. Additionally, differences in change in LVEF or associations between NT‐proBNP reduction and LVEF change were not affected with adjustment.

Safety

Treatment with S/V was well tolerated in both women and men (online supplementary Table S2 ).

Discussion

Previous studies have reported differences in biomarkers, health status and reverse remodelling after HF treatment between women and men 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ; however, data were lacking regarding these variables in women and men treated with S/V. In this post hoc analysis from PROVE‐HF of patients with HFrEF initiated on S/V, nearly 30% of subjects were women. Following initiation of S/V, both women and men demonstrated reduction in NT‐proBNP, though women had more consistency in NT‐proBNP change. Women had worse KCCQ‐23 scores than men at baseline but had much larger early gains in KCCQ‐23 scores compared to men after treatment with S/V. Importantly, women and men had similar improvement in cardiac remodelling parameters, but these changes tended to occur earlier in women. When adjusted for important covariates at baseline, these results remained similar. Lastly, S/V was well‐tolerated in both sexes.

The urgency of understanding sex‐based differences in HF cannot be overstated as incidence and prevalence of diagnosis have reached epidemic proportions with rise in both women and men. 14 The cornerstone of treatment of HFrEF entails optimization of therapies that reduce morbidity and mortality, 6 yet most landmark trials serving as basis of guideline recommendations enrolled low percentages of women 15 ; despite this, clinical practice guidelines apply to both women and men. Even with relatively permissive inclusion criteria and executed at a time of heightened urgency to include women in HF trials, it is worth noting that under 30% of subjects in PROVE‐HF were women. As development of therapies to reduce morbidity and mortality in HF continues, future clinical trials must aim for better representation, to ensure any differences in pathophysiology are identified and whether responses to HF therapies differ.

A potential sex‐independent remodelling benefit of S/V for those with HFrEF in this study is important. Beyond those with HFrEF, benefit of S/V on remodelling may not be restricted to those with LVEF <40%. A recent imputed placebo analysis suggests treatment benefits of S/V on risk of adverse cardiovascular events up to an LVEF of 60%, 16 and in those with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), women may benefit more from S/V than men. 17 Whether benefits of S/V in those with HFpEF indicate an effect on remodelling is not clear, however, the risk factors for remodelling differ substantially between HFrEF and HFpEF as does the biology; significant differences exist regarding location and pattern of cell death, microvascular changes, and fibrosis in both forms of HF. 18 More data are needed to understand how S/V affects remodelling across the range of LVEF.

In population‐representative surveys, natriuretic peptide concentrations increase to a lesser extent in women compared to men and only with severe LV dysfunction in women. 3 Despite this, women have greater frequency and larger magnitude of reverse cardiac remodelling compared to men. 3 In animal models, more favourable adaptations to chronic pressure overload have been linked to an attenuated increase in beta‐myosin heavy chain and atrial natriuretic peptide mRNA and a blunted decrease in sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca‐ATPase mRNA in female as compared to male rats. 3 , 19 Consistent with prior findings, women in PROVE‐HF had lower NT‐proBNP at baseline compared to men but despite this finding, women demonstrated similar improvement in cardiac reverse remodelling parameters associated with treatment with S/V. In both sexes, change in NT‐proBNP similarly correlated with improved cardiac remodelling parameters, findings that remained even after adjustment for ischaemic aetiology, LVEF, CRT presence and use of ACEi/ARB at baseline. Thus, despite quantitative differences in these parameters, clinicians should be reassured change in NT‐proBNP following S/V treatment imparts similar information regarding LV remodelling regardless of sex.

In this study, we found that women and men demonstrated comparable changes in LV remodelling parameters by the end of the study, though women showed these changes earlier. Female sex itself may be associated with greater frequency and magnitude of reverse cardiac remodelling compared to men. 20 Whether this reflects other unmeasured differences such as sex‐based variation in medication compliance is unclear. Of importance is the observation that regardless of baseline NT‐proBNP or LVEF, with adjustment for important baseline covariates, the extent of change in both measures was similar between women and men, suggesting a common, sex‐independent effect of S/V.

Women with HFrEF live longer than men; however, their additional years of life are poorer in quality, with greater self‐reported psychological and physical disability. 21 This is reflected in worse health status scores in tools such as the KCCQ. Consistent with this, a recent pooled analysis of 12 058 men and 3357 women enrolled in two recent HFrEF trials reported that women had worse KCCQ‐23 CS scores than men despite similar LVEF and NT‐proBNP. 21 This was unlike PROVE‐HF, where women had higher baseline LVEF and lower NT‐proBNP at baseline compared to men. However, women in PROVE‐HF had worse KCCQ‐23 scores at baseline. Intriguingly, early on after initiation of S/V, there was proportionally greater and more rapid improvement in the KCCQ‐23 scores in women. Further data are needed to better understand sex‐based differences in response to S/V on patient‐reported outcomes.

It has been noted that women have a 1.5‐ to 1.7‐fold greater risk of developing an adverse drug reaction compared with men for unclear reasons. These may include gender‐related differences in pharmacokinetic, immunological and hormonal factors as well as differences in the use of medications by women compared with men. 22 Little is known however about adverse drug reactions in women with HF treated with S/V due to scarcity of data stratified by sex. 23 Indeed, women and men may have different pharmacokinetics; however, it is difficult to know what the optimal maximum concentration of S/V for effect is for women vs. men. We found no difference in adverse events between women and men.

Several limitations exist for our analysis, including the observational, single‐group, open‐label design of the Phase 4 PROVE‐HF trial. Thus, we cannot compare differences in reverse remodelling among those taking S/V vs. ACEi/ARB. The reasons for this relate to the fact S/V was a class I guideline‐recommended treatment, and widely clinically available at the time of study execution, making it untenable to randomize patients. However, the comparison in this study was focused on change in NT‐proBNP, KCCQ‐23, and remodelling parameters between women and men after treatment with S/V; addition of a control group would not have altered the observation that initiation of S/V was associated with a substantial reverse remodelling among women and men in this study. As well, more than 80% of the study participants were taking ACEi/ARB at baseline and yet substantial reverse remodelling was noted. Unfortunately, we do not have baseline doses of ACEi/ARB or beta‐blocker. The comparisons are specific only to women and men with HFrEF treated with S/V and should not be translated to other HF therapies. Though our analysis comprised of a slightly higher percentage of women compared to other recent HFrEF studies, it is nonetheless somewhat limited in power and the first examination of sex‐based differences relative to S/V treatment. As this is a post hoc analysis, risk for residual confounding is present. Additionally, NT‐proBNP was not interpreted in the context of atrial fibrillation prevalence and renal function, both known to affect NT‐proBNP concentrations. Finally, this is a post hoc analysis from PROVE‐HF which carries inherent error of such analyses.

In conclusion, following S/V initiation, women and men both showed clinically similar changes in biomarkers, health status and remodelling parameters. Though similar overall, scrutiny of these changes revealed subtle sex‐based differences in NT‐proBNP reduction, KCCQ‐23 score change, and measures in cardiac reverse remodelling. These results provide clinicians reassuring data regarding potential benefits of ARNI therapy on health status and cardiac remodelling across sexes, while identifying further avenues for translational study of how reverse remodelling differs between women and men.

Funding

N.E.I. is supported in part by the Dennis and Marilyn Barry Research Fund in Cardiology (Boston, MA). J.L.J. is supported in part by the Hutter Family Professorship (Boston, MA).

Conflict of interest: N.E.I. has received honoraria from Roche Diagnostics. G.M.F. has received research grants from NHLBI, American Heart Association, Amgen, Merck, Cytokinetics, and Roche Diagnostics; he has acted as a consultant to Novartis, Amgen, BMS, Cytokinetics, Medtronic, Cardionomic, Relypsa, V‐Wave, Myokardia, Innolife, EBR Systems, Arena, Abbott, Sphingotec, Roche Diagnostics, Alnylam, LivaNova, Rocket Pharma, and SC Pharma. J.B. is a consultant for Abbott, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, CVRx, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Relypsa, Vifor. M.F.P. and C.A.A. are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals. S.D.S. has received research grants from Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Bayer, BMS, Celladon, Cytokinetics, Eidos, Gilead, GSK, Ionis, Lone Star Heart, Mesoblast, MyoKardia, NIH/NHLBI, Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos, and has consulted for Akros, Alnylam, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Cardior, Corvia, Cytokinetics, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Gilead, GSK, Ironwood, Merck, Myokardia, Novartis, Roche, Takeda, Theracos, Quantum Genetics, Cardurion, AoBiome, Janssen, Cardiac Dimensions, Tenaya. J.L.J. is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology, has received grant support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Applied Therapeutics, and Abbott Diagnostics, consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics, and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, CVRx, Janssen, and Takeda. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Strip plots of (A) left ventricular ejection fraction, (B) left ventricular end‐systolic volume index, and (C) left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index across time points as a function of sex.

Figure S2. Correlogram of growth factors for NT‐proBNP, LVEF, and KCCQ‐23 Total Symptom score.

Table S1. Bias‐adjusted estimators of standardized paired mean differences for select measures.

Table S2. Adverse events in women and men treated with sacubitril/valsartan.

References

- 1. Gori M, Lam CS, Gupta DK, Santos AB, Cheng S, Shah AM, Claggett B, Zile MR, Kraigher‐Krainer E, Pieske B, Voors AA, Packer M, Bransford T, Lefkowitz M, McMurray J, Solomon SD; PARAMOUNT Investigators . Sex‐specific cardiovascular structure and function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Kupka MJ, Ho KK, Murabito JM, Vasan RS. Long‐term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1397–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luchner A, Bröckel U, Muscholl M, Hense HW, Döring A, Riegger GA, Schunkert H. Gender‐specific differences of cardiac remodeling in subjects with left ventricular dysfunction: a population‐based study. Cardiovasc Res 2002;53:720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lam CS, Arnott C, Beale AL, Chandramouli C, Hilfiker‐Kleiner D, Kaye DM, Ky B, Santema BT, Sliwa K, Voors AA. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2019;40:3859–3868c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aimo A, Gaggin HK, Barison A, Emdin M, Januzzi JL Jr. Imaging, biomarker, and clinical predictors of cardiac remodeling in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:782–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Januzzi JL Jr, Prescott MF, Butler J, Felker GM, Maisel AS, McCague K, Camacho A, Piña IL, Rocha RA, Shah AM, Williamson KM, Solomon SD; PROVE‐HF Investigators . Association of change in N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide following initiation of sacubitril‐valsartan treatment with cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA 2019;322:1085–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Januzzi JL, Butler J, Fombu E, Maisel A, McCague K, Piña IL, Prescott MF, Riebman JB, Solomon S. Rationale and methods of the Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement, and Ventricular Remodeling During Sacubitril/Valsartan Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE‐HF). Am Heart J 2018;199:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonett D. Interval estimation of standardized mean differences in paired‐samples designs. J Educ Behav Stat 2015;40:366–376. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown AJ, Gandy S, McCrimmon R, Houston JG, Struthers AD, Lang CC. A randomized controlled trial of dapagliflozin on left ventricular hypertrophy in people with type two diabetes: the DAPA‐LVH trial. Eur Heart J 2020;41:3421–3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Lei Y, Leon MB, Smith CR, Svensson LG, Webb JG, Babaliaros VC, Bowers BS, Fearon WF, Herrmann HC, Kapadia S, Kodali SK, Makkar RR, Pichard AD, Cohen DJ; Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) Investigators . Health‐related quality of life after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2011;124:1964–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Vark LC, Lesman‐Leegte I, Baart SJ, Postmus D, Pinto YM, Orsel JG, Westenbrink BD, Brunner‐la Rocca HP, van Miltenburg AJ, Boersma E, Hillege HL, Akkerhuis KM; TRIUMPH Investigators . Prognostic value of serial ST2 measurements in patients with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2378–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Crespillo AP, Allison M, Hemingway H, Cleland JG, McMurray JJ, Rahimi K. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population‐based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet 2018;391:572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pilote L, Raparelli V. Participation of women in clinical trials: not yet time to rest on our laurels. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1970–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaduganathan M, Jhund PS, Claggett BL, Packer M, Widimský J, Seferovic P, Rizkala A, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, McMurray JJ, Solomon SD. A putative placebo analysis of the effects of sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure across the full range of ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2356–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McMurray JJ, Jackson AM, Lam CS, Redfield MM, Anand IS, Ge J, Lefkowitz MP, Maggioni AP, Martinez F, Packer M, Pfeffer MA, Pieske B, Rizkala AR, Sabarwal SV, Shah AM, Shah SJ, Shi VC, van Veldhuisen D, Zannad F, Zile MR, Cikes M, Goncalvesova E, Katova T, Kosztin A, Lelonek M, Sweitzer N, Vardeny O, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Solomon SD. Effects of sacubitril‐valsartan versus valsartan in women compared with men with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: insights from PARAGON‐HF. Circulation 2020;141:338–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simmonds SJ, Cuijpers I, Heymans S, Jones EA. Cellular and molecular differences between HFpEF and HFrEF: a step ahead in an improved pathological understanding. Cell 2020;9:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weinberg EO, Thienelt CD, Katz SE, Bartunek J, Tajima M, Rohrbach S, Douglas PS, Lorell BH. Gender differences in molecular remodeling in pressure overload hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aimo A, Vergaro G, Castiglione V, Barison A, Pasanisi E, Petersen C, Chubuchny V, Giannoni A, Poletti R, Maffei S, Januzzi JL Jr, Passino C, Emdin M. Effect of sex on reverse remodeling in chronic systolic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dewan P, Rørth R, Jhund PS, Shen L, Raparelli V, Petrie MC, Abraham WT, Desai AS, Dickstein K, Køber L, Mogensen UM, Packer M, Rouleau JL, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, McMurray JJ. Differential impact of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rademaker M. Do women have more adverse drug reactions? Am J Clin Dermatol 2001;2:349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bots SH, Groepenhoff F, Eikendal AL, Tannenbaum C, Rochon PA, Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Miller VM, Day D, Asselbergs FW, den Ruijter HM. Adverse drug reactions to guideline‐recommended heart failure drugs in women: a systematic review of the literature. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Strip plots of (A) left ventricular ejection fraction, (B) left ventricular end‐systolic volume index, and (C) left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index across time points as a function of sex.

Figure S2. Correlogram of growth factors for NT‐proBNP, LVEF, and KCCQ‐23 Total Symptom score.

Table S1. Bias‐adjusted estimators of standardized paired mean differences for select measures.

Table S2. Adverse events in women and men treated with sacubitril/valsartan.