SUMMARY

In plants, race‐specific defence against microbial pathogens is facilitated by resistance (R) genes which correspond to specific pathogen avirulence genes. This study reports the cloning of a blackleg R gene from Brassica napus (canola), Rlm9, which encodes a wall‐associated kinase‐like (WAKL) protein, a newly discovered class of race‐specific plant RLK resistance genes. Rlm9 provides race‐specific resistance against isolates of Leptosphaeria maculans carrying the corresponding avirulence gene AvrLm5‐9, representing only the second WAKL‐type R gene described to date. The Rlm9 protein is predicted to be cell membrane‐bound and while not conclusive, our work did not indicate direct interaction with AvrLm5‐9. Rlm9 forms part of a distinct evolutionary family of RLK proteins in B. napus, and while little is yet known about WAKL function, the Brassica–Leptosphaeria pathosystem may prove to be a model system by which the mechanism of fungal avirulence protein recognition by WAKL‐type R genes can be determined.

Keywords: Leptosphaeria maculans, blackleg, Brassica napus, Rlm9, AvrLm5‐9, disease resistance, wall‐associated kinase‐like

Significance Statement

Rlm9 encodes a wall‐associated kinase‐like (WAKL) race‐specific resistance protein, is a member of an emerging class of race‐specific plant receptor‐like kinase resistance genes and is the first of its kind to be cloned from a dicot species.

INTRODUCTION

Plants detect invading microbial pathogens through the perception of ‘danger signals’ (Gust et al., 2017). Perception of microbe‐associated molecular patterns by extracellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), consisting of various receptor‐like kinases (RLKs) and receptor‐like proteins (RLPs), initiates host pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP)‐triggered immunity (PTI), the first layer of defence against pathogens. PRRs also respond to damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as host peptides and oligosaccharide fragments, including pectin‐derived oligogalacturonides, released during pathogen breaching of the plant cell wall (Yang et al., 2012; Zipfel, 2014; Boutrot and Zipfel, 2017). Pathogens have evolved to overcome PTI by secreting small proteins called effectors, which often target components of the plant’s defence pathways. In turn plants are armed with an array of highly diverse resistance (R) genes which encode both cytoplasmic and extracellular receptors to perceive pathogen effectors and trigger a rapid and robust immune response called effector‐triggered immunity (ETI) (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Bent and Mackey, 2008; Stotz et al., 2014). However, PTI and ETI share common signaling pathways (Katagiri and Tsuda, 2010) and the distinction between the two responses is blurred (Thomma et al., 2011; Rodriguez‐Moreno et al., 2018). In light of the ambiguities and commonalities observed, a more general model encompassing all plant immune responses and based on ‘immunogenic patterns’ instead separates responses into extracellular‐ and intercellular‐triggered immunity, based on the point of recognition by the host cell (van der Burgh and Joosten, 2019).

Plant RLK proteins are encoded by a large and diverse gene family which underwent massive expansion after the divergence of the plant and animal lineages (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001). RLKs are defined by a common set of domains; a signal peptide, an extracellular receptor domain, a single transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic kinase domain. The extracellular regions of the proteins vary, and are adapted to the recognition of diverse signals. Based on their conserved intracellular kinase domains, plant RLKs form a monophyletic group distinct from other eukaryotic kinases (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001). Membrane‐bound RLPs, which feature extracellular leucine‐rich repeat domains involved in protein recognition but lack the intracellular kinase domain of RLKs, constitute a class of R proteins that confer resistance upon perception of apoplastic pathogen effectors (Stotz et al., 2014; Jamieson et al., 2018). We previously reported the cloning of two RLP‐type resistance genes, LepR3 and Rlm2, residing in the A genome of the allotetraploid Brassica napus (canola, rapeseed) (Larkan et al., 2013; Larkan et al., 2015), conferring resistance against races of the fungal pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans (Lm) with the matching effectors AvrLm1 and AvrLm2, respectively (Gout et al., 2006; Ghanbarnia et al., 2015). Both LepR3 and Rlm2 pair with the RLK SOBIR1 (Ma and Borhan, 2015; Larkan et al., 2015), as RLPs, lacking any intracellular kinase, require a partner to transmit a signal across the plasma membrane and to activate cytoplasmic signal transduction cascades (Liebrand et al., 2014).

The Brassica R genes Rlm3, Rlm4, Rlm7 and Rlm9 confer race‐specific resistance against blackleg disease caused by L. maculans. They form a tight genetic cluster on chromosome A07 and may possibly be allelic variants of the same R locus (Larkan et al., 2016). The corresponding avirulence (Avr) genes AvrLm3, AvrLm4‐7 and AvrLm5‐9 have been cloned from L. maculans and all encode small cysteine‐rich secreted proteins (Parlange et al., 2009; Plissonneau et al., 2016; Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). Recognition of both AvrLm3 and AvrLm5‐9 by Rlm3 and Rlm9, respectively, is masked in the presence of AvrLm4‐7. However, AvrLm4‐7 neither interferes with the expression of, nor directly interacts with, AvrLm3 or AvrLm5‐9, nor do AvrLm3 and AvrLm5‐9 interact (Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). To investigate this complex system of pathogen recognition we have pursued the cloning of Brassica R genes from the Rlm3/4/7/9 gene cluster. Here we report cloning of Rlm9 from the B. napus cultivar Darmor and show that it encodes a wall‐associated kinase‐like (WAKL) protein, a newly emerging class of race‐specific plant RLK R genes (Keller and Krattinger, 2018).

RESULTS

Rlm9 encodes a wall‐associated kinase‐like protein

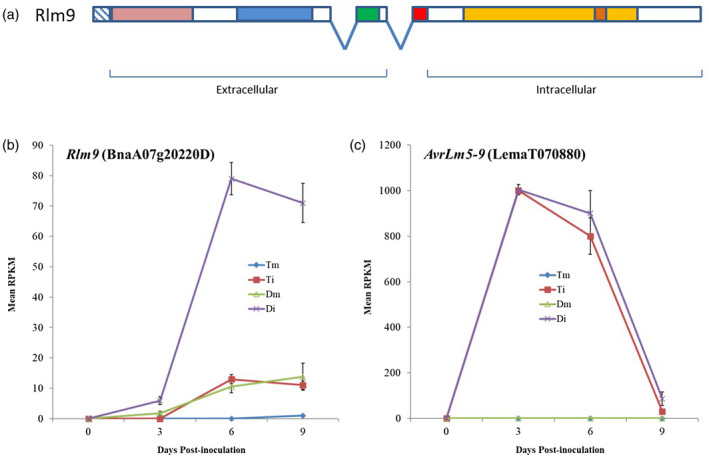

Through molecular mapping, the physical interval of the Rlm9 locus had previously been defined as approximately 4.3 Mb of chromosome A07 (Larkan et al., 2016) of the B. napus reference genome Darmor‐bzh (Chalhoub et al., 2014), an Rlm9 variety. Rlm9 is genetically clustered with the other blackleg R genes Rlm3, Rlm4 and Rlm7, all of which were shown to co‐segregate with the microsatellite marker sR7018 positioned at approximately 16 Mb on chromosome A07 (Larkan et al., 2016). Using this information along with previously generated genomic information for the Rlm3 locus (Mayerhofer et al., 2005) we searched the consensus physical interval of the overlapping Rlm3‐4‐7‐9 maps (230 genes; Larkan et al, 2016) on the B. napus Darmor‐bzh (Rlm9) genome for genes with similarity to R genes and expression in response to pathogen infection. BnaA07g20220D, a WAKL protein encoding gene, was identified as the best candidate for Rlm9. No other defence‐related candidates were identified within the interval (Table S1). Rlm9 is predicted to encode a 794‐amino acid protein with the typical features of the WAKL family of Arabidopsis thaliana (Verica and He, 2002), showing the highest homology to A. thaliana WAKL10 (At1g79680, 69% amino acid identity). The gene contains three exons encoding a transmembrane receptor protein, which contains predicted extracellular domains for pectin‐ and calcium‐binding (wall‐associated receptor kinase galacturonan‐binding [GUB_WAK] and epithelial growth factor [EGF]‐like Ca2+ domains, respectively), a C‐terminal WAK domain and an intracellular serine/threonine protein kinase domain with a guanylyl cyclase (GC) motif (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

(a) Domain organisation of the Rlm9 protein. The protein consists of three exons (introns denoted by ‘V’) and contains a predicted signal peptide (hashed box), extracellular GUB_WAK pectin‐binding (light red), C‐terminal WAK (blue) and EGF‐like Ca2+ (green) domains, a transmembrane motif (red) and an intracellular serine/threonine protein kinase domain (light orange) with a guanylyl cyclase centre (dark orange). (b,c) Expression profile of Rlm9 and AvrLm5‐9 alleles during infection by L. maculans. (b) Mean reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) for mock (m) and L. maculans‐infected (i) cotyledon lesions from B. napus lines Topas DH16516 (T – rlm9) and Darmor (D – Rlm9), showing significant upregulation of Rlm9 between both Dm and Di and between Di and Ti, at all timepoints after zero. (c) Mean RPKM values for fungal AvrLm5‐9 during the same experiment, showing no significant difference in expression between Di and Ti.

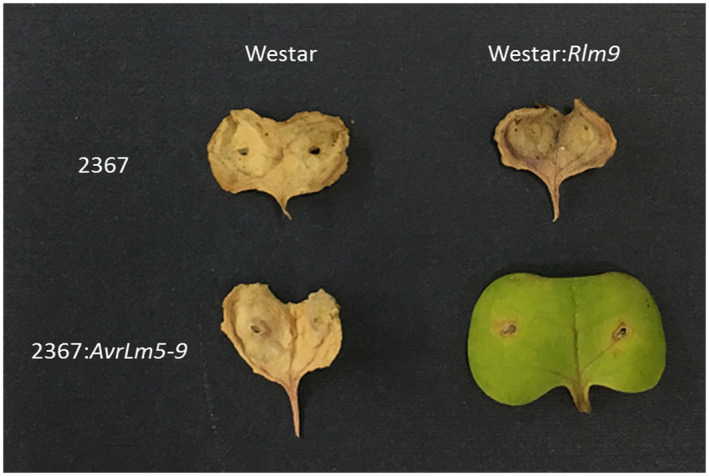

BnaA07g20220D, including native promoter and terminator regions, was isolated from Darmor and transferred to the susceptible B. napus cultivar Westar N‐o‐1. After transgenic events were analysed in the T0 generation by droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR), four independent transgenic lines, carrying between 1 and 9 copies of the transgene, were selected for phenotypic analysis. Selfed seeds of each line (T1) were inoculated with the L. maculans isolate 2367 (avr9; virulent towards Rlm9) and the transgenic L. maculans isolate 2367:AvrLm5‐9 (Avr9; avirulent towards Rlm9; Ghanbarnia et al., 2018) using standard cotyledon infection protocols (Larkan et al., 2013). The race‐specific resistance response was activated in all Westar:BnaA07g20220D transgenic lines, confirming that the WAKL gene is indeed Rlm9 (Figure S1). Further ddPCR analysis of the T1 plants derived from the transgenic line NLA68 (one heterozygous transgene insertion at T0; Table S2) allowed for selection of a T1 plant carrying a single homozygous insertion which was self‐fertilised to produce homozygous T2 seed (hereafter referred to as Westar:Rlm9; Figure 2). Further testing of Westar:Rlm9 with additional transgenic isolates carrying avirulence genes matching other A07 blackleg R genes (2367:AvrLm1, 2367:AvrLm3, 2367:AvrLm4‐7, 2367:AvrLm7) produced only compatible interactions (i.e., host was susceptible to infection; Table S3) as previously demonstrated (Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). Stable expression of the Rlm9 resistance phenotype (hypersensitive response [HR] indicated by blackening around the point of inoculation) was observed in all cases (four inoculations per seedling, four seedlings per test; Figure 2). This reconfirmed both the identity of BnaA07g20220D as Rlm9 and the specificity of the Rlm9–AvrLm5‐9 interaction.

Figure 2.

Transgenic complementation of the Rlm9 phenotype in B. napus. Cotyledons of Westar (no R gene) and a Westar:Rlm9 transgenic line infected with L. maculans, 14 days post‐infection: isolate 2367 (phenotype a9 – virulent towards Rlm9) and the transgenic isolate 2367:AvrLm5‐9 (phenotype A9 – avirulent toward Rlm9).

An identical Rlm9 allele was identified from the genome sequence of B. napus var. Tapidor (Bayer et al., 2017), which also harbours Rlm9 (Larkan et al., 2016) (Table S4). A susceptible allele (rlm9; Table S4) was obtained from the genome sequence (v2.0) of B. napus var. ZS11 (He et al., 2015). The Brassica rapa var. Chiifu homologue (Bra003598 – unknown Rlm9 phenotype) (Wang et al., 2011) was also included for comparison studies. Comparison of the Darmor (resistant) Rlm9 and ZS11 (susceptible) rlm9 proteins (95.72% identity overall, Figure S2) revealed that most of the variation appeared concentrated in the predicted pectin‐binding (GUB_WAK) domains (15 substitutions within the 119‐amino acid domain; 87.39% identity), while the C‐terminal WAK and EGF‐like domains were well conserved (94.69% and 100% identity, respectively).

RNA‐Seq time course analysis revealed a significant upregulation of Rlm9 during L. maculans infection (isolate 00‐100; A2‐3‐5‐6‐(8)‐9‐10‐L1‐L2‐L4) with an approximately 5‐fold increase early in the infection (3 days post‐inoculation, FDR < 0.03) and a nearly 8‐fold increase in transcript abundance detected at 6 days post‐infection (FDR < 0.001) in the Rlm9 variety Darmor when compared to a susceptible (rlm9) variety Topas DH16516 or the mock (water)‐inoculated control. No significant difference was detected in the expression of the fungal AvrLm5‐9 between the inoculated susceptible and resistant lines over the same time course (Figure 1(b)). Expression of the B. napus SOBIR1 and BAK1 genes, previously shown to interact with the B. napus RLP‐type R genes Rlm2 and LepR3 (Larkan et al., 2013; Larkan et al., 2015), was upregulated (up to 15‐fold) during infection of the Rlm2 plants. However, in the infected Rlm9 plants, both the SOBIR1 and BAK1 homologues (six copies each in B. napus) showed little upregulation (1–2 fold), suggesting they may not be involved in the same manner during the WAKL R gene response (Figure S3).

Confirmation of Rlm9 in B. napus varieties

A selection of 22 B. napus cultivars, including many either previously identified as Rlm9 lines or suspected to harbour Rlm9 based on previous differential pathology, and the introgression line Topas‐Rlm9 were tested for the presence of the Rlm9 allele. The presence of Rlm9 was first confirmed via infection with the transgenic L. maculans isolate 2367:AvrLm5‐9, which induced an HR in all 13 Rlm9 lines (Table S4, Figure S4). All lines were susceptible to the non‐transgenic 2367 isolate. The allele was successfully amplified from each of the 13 Rlm9 lines (Table S4), while only weak non‐specific amplicons were produced from non‐Rlm9 lines, including cultivars containing other A07 blackleg R genes (Rlm1, Rlm3, Rlm4 and Rlm7).

No direct physical interaction detected between Rlm9 and either AvrLm5‐9 or AvrLm4‐7

Recently, we reported the cloning of the L. maculans effector AvrLm5‐9 (Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). As previously reported, recognition of AvrLm5‐9 and AvrLm3 by their cognate R proteins, Rlm9 and Rlm3, is masked in the presence of AvrLm4‐7 and this masking effect is neither due to direct interaction between these effector proteins nor due to the suppression of their transcription (Plissonneau et al., 2016; Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). To examine whether AvrLm5‐9 directly interacts with Rlm9, we cloned the extracellular region of Rlm9 in the prey vector pGADT7 and AvrLm5‐9 lacking the signal peptide sequences (ΔspAvrLm5‐9) in the bait vector pGBKT7 for yeast two‐hybrid assay. The assay was performed by co‐transforming the bait and prey constructs into the yeast strain Y2HGold. The combination of the L. maculans effector ΔspAvrLm1 (bait) and its B. napus host‐interacting protein BnMPK9 (Ma et al., 2018) (prey) was used as a positive control. No interaction could be detected between ΔspAvrLm5‐9 and the extracellular region of Rlm9 (Figure S5). To assess whether AvrLm4‐7, which masks the recognition of AvrLm5‐9 by Rlm9, directly interacts with either the extracellular region or the kinase domain of Rlm9 to supress Rlm9‐mediated resistance, we co‐transferred the bait vector pGBKT7:ΔspAvrLm4‐7 and either prey vector pGADT7:Rlm9‐EX or pGADT7:Rlm9‐KD to yeast. As shown in Figure S5 there was no interaction between ΔspAvrLm4‐7 and Rlm9‐EX or Rlm9‐KD, indicating that the masking of Rlm9‐mediated resistance by AvrLm4‐7 is not due to the direct interaction of AvrLm4‐7 and Rlm9.

Evolution of the WAKL gene family in B. napus

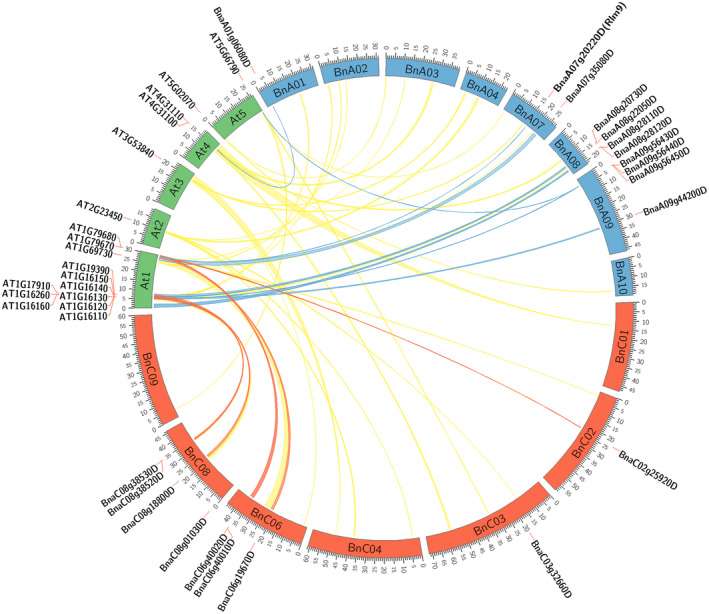

To compare the evolution of the WAKL gene family between A. thaliana and B. napus, predicted WAKL‐encoding genes, those encoding proteins with homology to the external domain of Rlm9, were extracted from the Darmor‐bzh reference B. napus genome. After annotation, 19 additional genes encoding potential functional RLKs (predicted proteins containing Signal Peptide (SP), Trans‐Membrane (TM) and Protein Kinase (PK) domains) were identified. All predicted proteins contained GUB_WAK domains, 18 also contained C‐terminal WAK domains, while 16 of the 19 contained EGF‐Like domains. WAKLs were distinguished from WAKs based on homology to A. thaliana WAKLs, the presence of a C‐terminal WAK domain and the lack of twin EGF domains found in WAKs (Table S5). The predicted B. napus WAKLs were found to be largely clustered on two chromosomes in each of the A (A08 and A09) and C (C06 and C08) genomes (Figure 3). Genomic alignment between syntenic A. thaliana blocks containing 18 of the previously characterised 22 AtWAKLs (Verica and He, 2002) which also encode intact RLKs, and the two genomes of B. napus revealed that almost all of the predicted WAKLs in B. napus are syntenic to the WAKL genes clustered on A. thaliana chromosome 1 (Figure 3). Comparison of WAKL GUB_WAK domains to AtWAK1 showed that none of the four amino acid residues previously identified as contributing to homogalacturonan binding within the AtWAK1 GUB_WAK domain (Decreux et al., 2006) are conserved in either the resistant or susceptible alleles of Rlm9, nor in AtWAKL10, and show generally poor conservation in both WAKL and WAK predicted proteins from B. napus (Figure S6(a)). Phylogenetic analysis for the predicted GUB_WAK domains also suggests that the WAKL proteins are a distinct evolutionary group from WAKs (Figure S6(b)).

Figure 3.

Syntenic alignment of A. thaliana and B. napus WAKL genomic regions. Genomic alignment between A. thaliana genomic blocks containing WAKL genes (‘AT…’ labels) and their syntenic matches in the B. napus A and C genomes. B. napus genes predicted to encode intact WAKL proteins are labelled ‘Bna…’. Syntenic links between A. thaliana and B. napus WAKLs are indicated by blue (A genome) and red (C genome) ribbons. Yellow ribbons indicate syntenic matches where no corresponding B. napus WAKL was found.

DISCUSSION

The number of characterised race‐specific resistance (R) genes has significantly expanded since the cloning of the first R gene in 1992, with the majority of described R genes encoding intracellular nucleotide‐binding domain leucine‐rich repeat/nucleotide binding and oligomerisation domain‐like receptors (Zhang et al., 2017; Kourelis and Van Der Hoorn, 2018). However, a number of cell surface receptor proteins, collectively referred to as plant PRRs, which are involved in the recognition of extracellular plant pathogens, both through PAMPs and specific effectors, have also been identified (Boutrot and Zipfel, 2017). Rlm9 and the recently cloned wheat (Triticum aestivum) Stb6 are the only examples of race‐specific WAKL‐type R genes to be reported to date. Stb6 confers resistance to races of the apoplastic fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici which produce the matching effector AvrStb6, though resistance is semi‐dominant and conferred without a typical HR (Zhong et al., 2017; Saintenac et al., 2018). In contrast, Rlm9 induces a clear, dominant HR at the site of infection, responding to the presence of the L. maculans avirulence protein AvrLm5‐9 (Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). The emergence of WAKL proteins as new players in race‐specific resistance brings with it many fundamental questions. Using yeast two‐hybrid we did not detect a direct interaction between AvrLm5‐9 and Rlm9, which was also reported to be the case between Stb6 and AvrStb6 (Saintenac et al., 2018). Although yeast two‐hybrid is not an optimal test to detect direct interaction of membrane proteins, it is possible that Rlm9 recognition of AvrLm5‐9 is indirect and mediated by a host target molecule. One such molecule could be a DAMP, for example, a pectin monomer. However, the mechanism by which these predicted pectin‐binding proteins function as mediators of race specificity has yet to be determined. The Stb6 protein contains a predicted extracellular GUB_WAK domain but does not contain either the C‐terminal WAK or EGF‐like Ca2+ domains found in Rlm9 and most other WAKL proteins (Saintenac et al., 2018), which suggests that these domains could be dispensable for the WAKL‐mediated effector‐triggered immune response. The concentration of variation in the GUB_WAK domain between the resistant Rlm9 and susceptible rlm9 proteins in comparison to the other well‐conserved extracellular domains (C‐terminal WAK and EGF‐like domains) also suggests that the GUB_WAK domain may play a pivotal role in recognition of AvrLm5‐9. While the GUB_WAK domain of the A. thaliana WAK1 protein has been demonstrated to bind cell‐wall pectins (Decreux and Messiaen, 2005) and WAKL proteins have been suggested to be associated with the cell wall (Verica and He, 2002; Hou et al., 2005), the same pectin‐binding activity has yet to be shown for the predicted GUB_WAK domains of the WAKL proteins, and much research needs to be undertaken before we can determine how these RLKs function. However, at present it should not be assumed that these proteins retain the ability to bind pectin. It may be that the protein originally functioned as a general DAMP receptor, as for AtWAK1 (Brutus et al., 2010), and that these proteins later evolved into a more specialised role in the detection of proteinaceous ligands, in this case AvrLm5‐9. As the conservation between WAKs and WAKLs appears in the EGF and kinase domains, rather than the putative pectin‐binding regions, it may be more appropriate to consider WAKs and WAKLs as subsets of the EGF protein superfamily, rather than grouping both WAKs and WAKLs together as ‘wall‐associated’ proteins (Kohorn, 2016).

In A. thaliana, Rlm9 shares the highest protein homology with WAKL10 (At1g79680.1). AtWAKL10 is co‐expressed with several pathogen response genes during biotic interactions. The protein kinase domain has been shown to be a twin‐domain, also having GC activity (Meier et al., 2010). Rlm9 contains an identical GC motif (SFGVVLAELITGEK) within the PK domain. GCs convert guanosine 5′‐triphosphate (GTP) into guanosine 3′,5′‐cyclic monophosphate (cGMP), an important signaling molecule during biotic interactions (Durner et al., 1998; Gehring and Turek, 2017). Plant cGMP‐binding proteins include several actors in defence response pathways, including hydrogen peroxide production (Donaldson et al., 2016). The potential GC activity of Rlm9 could be a key component of the HR to L. maculans infection. Interestingly, the wheat Stb6 protein, which does not trigger an HR (Saintenac et al., 2018), appears to lack a GC centre in its kinase domain.

A search for WAKL homologues within the B. napus genome showed far fewer intact genes than was expected. B. napus is an amphidiploid hybrid of B. rapa (A genome) and Brassica oleracea (C genome), with each diploid genome having evolved from a hexaploid ancestor, with some gene loss occurring over time (Parkin et al., 2005; Ziolkowski et al., 2006). Therefore, for each single A. thaliana gene there are generally expected to be six homologues within B. napus (Grant et al., 1998). Despite there being 22 WAKLs characterised in A. thaliana (Verica and He, 2002), we were only able to identify 19 intact WAKL genes predicted within the B. napus Darmor sequence which are predicted to retain the SP, TM and PK domains required to function as an RLK (Table S5). This suggests a disproportionate evolution of the genes since the Arabidopsis–Brassica split 20–24 million years ago (Ziolkowski et al., 2006). This may be due to functional redundancy, making many of the WAKL homologues within the amphidiploid genome of B. napus dispensable. The relative abundance of WAKL genes in A. thaliana may also be due to a higher rate of gene expansion, as evidenced by the dense clusters of WAKL homologues and abundant tandem duplications found on A. thaliana chromosome 1 (12 genes total; Verica and He, 2002) which are only partially represented within each of the B. napus A and C genomes as homologues, while several AtWAKLs found on other chromosomes do not appear to be represented by intact genes in B. napus, despite syntenic links between the genomes (Figure 3).

As we recently reported, the recognition of AvrLm5‐9 by Rlm9 is masked in the presence of AvrLm4‐7 (Ghanbarnia et al., 2018). Similarly, AvrLm3 recognition by Rlm3 is also masked in the presence of AvrLm4‐7 (Plissonneau et al., 2016). With the cloning of Rlm9 and the characterisation of the gene as a WAKL we now have the basis for possibly identifying the other three blackleg R genes within the Rlm3/4/7/9 cluster, co‐located on chromosome A07 (Larkan et al., 2016). Though Rlm9 is the only A07 blackleg R gene carried by any of the published B. napus genomes (we identified the same Rlm9 allele in both Darmor (Chalhoub et al., 2014) and Tapidor (Bayer et al., 2017), and showed a lack of specific R genes in ZS11 (He et al., 2015) during this study), previous investigations into the blackleg resistance carried by DH12075, a doubled‐haploid F1‐derived line from Westar (no R gene) and Cresor (Rlm3; Larkan et al., 2016) parents, identified three WAKL genes in the same location. We are currently investigating the allelic variation of the Rlm9 locus in multiple B. napus accessions carrying Rlm3, Rlm4 and Rlm7 through parental‐specific genome resequencing. If these genes prove to be variants or duplications of the same WAKL locus we can potentially gain further insight as to the evolution of WAKL‐type R genes, and the Brassica–Leptosphaeria pathosystem may prove to be a model system by which the mechanism of fungal avirulence protein recognition by WAKLs can be determined.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Candidate identification and transformation

The BnaA07g20220D gene, including 1000 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the predicted coding sequence (4141 bp total), was PCR‐amplified (Q5 High‐Fidelity 2× Master Mix, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) from Darmor DNA, verified by Sanger sequencing and transferred to the Gateway‐compatible transformation vector pMDC123 (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003). The same primers (GW‐DarWAKL F + R; Table S6) were used to survey a selection of B. napus cultivars to confirm the presence of the target allele in multiple Rlm9 sources. The genomic candidate construct was transformed via Agrobacterium into the susceptible B. napus cultivar Westar N‐o‐1 as previously described (Larkan et al., 2013). Homozygous, single‐insertion transgenic plants were selected in the T1 generation using ddPCR (Larkan et al., 2015). Final confirmation of phenotype was performed using the transgenic L. maculans isolate 2367:AvrLm5‐9 (Ghanbarnia et al., 2018) using standard cotyledon infection protocols (Larkan et al., 2013). Briefly, 7‐day‐old cotyledons were wounded once per lobe (four wounds per seedling, four seedlings per test) and inoculated with L. maculans pycnidiospore suspension. The resistance response was rated 14 days post‐inoculation on a 0 (no infection) to 9 (complete necrotic collapse) scale.

Transcript analysis

Transcription time course profiles were generated by RNA‐Seq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for the B. napus cultivars Topas DH16516 (no R gene) and Darmor (Rlm9) during infection with the L. maculans isolate 00–100 (avirulence profile A2‐3‐5‐6‐(8)‐9‐(10)‐L1‐L2‐L4 (Larkan et al., 2016)) with sampling at 0, 3, 6 and 9 days after inoculation. Additional data for the lines Topas‐Rlm2 and Topas‐Rlm3, growth conditions, tissue sampling, RNA processing and read mapping protocols were as previously described (Becker et al., 2019; Haddadi et al., 2019). Confirmation of the predicted coding region and protein sequence was obtained by aligning merged RNA sequencing reads to the Darmor genome sequence using Bowtie2 (http://bowtie‐bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/manual.shtml) and CLC Genomics Workbench 11 (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/clc‐genomics‐workbench/).

Yeast two‐hybrid assay

For the yeast two‐hybrid assay, AvrLm5‐9 lacking the signal peptide sequence was cloned into the pGBKT7 bait vector with primer set ΔspAvrLm5‐9‐NcoI/ΔspAvrLm5‐9‐EcoRI, and AvrLm4‐7 lacking the signal peptide sequence was cloned into pGBKT7 with primer set ΔspAvrLm4‐7NdeI/ΔspAvrLm4‐7‐PstI. The intracellular kinase domain of Rlm9 was cloned into the pGADT7 prey vector with primer set Rlm9‐KD‐NdeI/Rlm9‐KD‐EcoRI and the extracellular region of Rlm9 was cloned into pGADT7 with primer set Rlm9‐EX‐NedI/Rlm9‐EX‐EcoRI (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). All primers are listed in Table S6. We used the matchmaker GLA4 two‐hybrid system and yeast strain Y2HGold (Clontech). The yeast strain Y2HGold was co‐transformed with bait and prey plasmid combinations using lithium‐acetate and polyethylene glycol 3350 following the manufacturer’s manual. Transformants harboring both bait and prey plasmids were selected on plates containing minimal medium lacking Leu and Trp (SD‐WL). Empty prey vector pGBKT7 or pGADT7 used as bait or prey served as controls. pGBKT7:ΔspAvrLm1 and pGADT7:BnMPK9 were used as positive control (Ma et al., 2018). One colony per combination was picked from SD‐WL plates to inoculate 1 ml SD‐WL culture. After 36 h of growth, cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 25 µl 0.9% NaCl from OD600 = 1 to OD600 = 0.00001 and spotted on SD‐WL and SD‐AHWL plates supplemented with 40 μg ml−1 X‐α‐Gal (Clontech) and 200 ng ml−1 Aureobasidin A (Clontech). After 3 days of incubation, the plates were checked for growth and photographed.

Genomic and phylogenetic analyses

Predicted B. napus WAKL protein sequences, matching the extracellular domain of Rlm9, were retrieved from the Darmor‐bzh reference annotation (Chalhoub et al., 2014) using the blastp function (default values) in CLC Genomics Workbench v12. Protein sequences with >20% identity to Rlm9 were annotated using InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/). Only those proteins containing predicted domains required for RLK function (SP, TM and PK) were included as potential functional WAKLs (Table S5). An additional tblastn search comparing all predicted Darmor genes to the annotated A. thaliana proteins was also performed and all genes with best matches to ‘wall‐associated’ proteins were retrieved and analysed as described above. The homology between A. thaliana TAIR10 (Wensel et al., 2011) and Brassica napus Darmor‐bzh (Chalhoub et al., 2014) was visualised using Circos (Krzywinski et al., 2009). Orthologous gene pairs identified from synteny analysis were used to determine regions of homology and intersections with the defined B. napus WAKL genes using BEDTools intersect (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Multiple sequence alignments and dendrograms were produced using CLC Workbench v7.9.1 software.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

NJL and MHB conceived and planned the study. NJL, LM and MD conducted the experiments. PH and MB performed the bioinformatic analysis. IAPP provided the genome sequence and contributed to the data analysis. NJL and MHB prepared the manuscript draft and all authors helped with the revision and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

OPEN RESEARCH BADGES

This article has earned an Open Materials Badge for making publicly available the components of the research methodology needed to reproduce the reported procedure and analysis.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Phenotypic reaction of B. napus lines and T1 transgenics to AvrLm5‐9 transgenic L. maculans isolate.

Figure S2. Protein sequence alignment for resistant and susceptible proteins.

Figure S3. Expression of B. napus SOBIR1 and BAK1 homologues.

Figure S4. Transgenic confirmation of Rlm9 phenotype in B. napus varieties.

Figure S5. Yeast two‐hybrid assay.

Figure S6A . Multiple sequence alignment and dendrogram for GUB_WAK domains.

Table S1. Rlm9 interval of the B. napus genome (Darmor‐bzh).

Table S2. Insert copy number and phenotypic reaction for Rlm9 transgenic B. napus lines.

Table S3. Transgenic Avr–Rlm9 interactions.

Table S4. Rlm9 PCR and pathological interactions for B. napus lines.

Table S5. B. napus WAKL and WAK protein matches.

Table S6. PCR primers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Elena Beynon, Colin Kindrachuk, Gordon Gropp, Catherine Guenther, Justin Skurdal and Erica Boyer for their technical assistance and Delwin Epp for generating the B. napus transgenic lines. Funding support for this project was provided by SaskCanola and Agriculture and Agri‐Food Canada.

Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Agriculture & Agri‐Food Canada.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All relevant data can be found within the manuscript and its supporting materials.

REFERENCES

- Bayer, P.E. , Hurgobin, B. , Golicz, A.A. et al (2017) Assembly and comparison of two closely related Brassica napus genomes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15(12), 1602–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.G. , Haddadi, P. , Wan, J. , Adam, L. , Walker, P. , Larkan, N.J. , Daayf, F. , Borhan, M.H. and Belmonte, M.F. (2019) Transcriptome analysis of Rlm2‐mediated host immunity in the Brassica napus‐Leptosphaeria maculans pathosystem. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 32(8), 1001–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent, A.F. and Mackey, D. (2008) Elicitors, effectors, and R genes: the new paradigm and a lifetime supply of questions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45, 399–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrot, F. and Zipfel, C. (2017) Function, discovery, and exploitation of plant pattern recognition receptors for broad‐spectrum disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 55, 257–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutus, A. , Sicilia, F. , Macone, A. , Cervone, F. and De Lorenzo, G. (2010) A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall‐associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 107(20), 9452–9457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub, B. , Denoeud, F. , Liu, S. et al . (2014) Early allopolyploid evolution in the post‐Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science, 345(6199), 950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M.D. and Grossniklaus, U. (2003) A gateway cloning vector set for high‐throughput functional analysis of genes in planta . Plant Physiol. 133(2), 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreux, A. and Messiaen, J. (2005) Wall‐associated kinase WAK1 interacts with cell wall pectins in a calcium‐induced conformation. Plant Cell Physiol. 46(2), 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreux, A. , Thomas, A. , Spies, B. , Brasseur, R. , Cutsem, P.V. and Messiaen, J. (2006) In vitro characterization of the homogalacturonan‐binding domain of the wall‐associated kinase WAK1 using site‐directed mutagenesis. Phytochemistry, 67(11), 1068–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L. , Meier, S. and Gehring, C. (2016) The Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide interactome. Cell Commun. Signal. 14(1), 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durner, J. , Wendehenne, D. and Klessig, D.F. (1998). Defense gene induction in tobacco by nitric oxide, cyclic GMP, and cyclic ADP‐ribose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 95(17), 10328–10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, C. and Turek, I.S. (2017) Cyclic nucleotide monophosphates and their cyclases in plant signaling. Front. Plant Sci., 8, 1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbarnia, K. , Fudal, I. , Larkan, N.J. , Links, M.G. , Balesdent, M.‐H. , Profotova, B. , Fernando, W.G.D. , Rouxel, T. and Borhan, M.H. (2015) Rapid identification of the Leptosphaeria maculans avirulence gene AvrLm2 using an intraspecific comparative genomics approach. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16(7), 699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbarnia, K. , Ma, L. , Larkan, N.J. , Haddadi, P. , Fernando, W.G.D. and Borhan, M.H. (2018) Leptosphaeria maculans AvrLm9: a new player in the game of hide and seek with AvrLm4‐7. Mol. Plant Pathol., 19(7), 1754–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout, L. , Fudal, I. , Kuhn, M.‐L. , Blaise, F. , Eckert, M. , Cattolico, L. , Balesdent, M.‐H. and Rouxel, T. (2006) Lost in the middle of nowhere: The AvrLm1 avirulence gene of the Dothideomycete Leptosphaeria maculans . Mol. Microbiol. 60(1), 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.R. , McDowell, J.M. , Sharpe, A.G. , de Torres Zabala, M. , Lydiate, D.J. and Dangl, J.L. (1998) Independent deletions of a pathogen‐resistance gene in Brassica and Arabidopsis . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95(26), 15843–15848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust, A.A. , Pruitt, R. and Nürnberger, T. (2017) Sensing danger: key to activating plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 779–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddadi, P. , Larkan, N.J. and Borhan, M.H. (2019) Dissecting R gene and host genetic background effect on the Brassica napus defense response to Leptosphaeria maculans . Sci. Rep. 9(1), 6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Z. , Cheng, F. , Li, Y. , Wang, X. , Parkin, I.A.P. , Chalhoub, B. , Liu, S. and Bancroft, I. (2015) Construction of Brassica A and C genome‐based ordered pan‐transcriptomes for use in rapeseed genomic research. Data in Brief, 4, 357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X. , Tong, H. , Selby, J. , DeWitt, J. , Peng, X. and He, Z.H. (2005) Involvement of a cell wall‐associated kinase, WAKL4,. Arabidopsis mineral responses. Plant Physiol. 139(4), 1704–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, P.A. , Shan, L. and He, P. (2018) Plant cell surface molecular cypher: Receptor‐like proteins and their roles in immunity and development. Plant Sci. 274, 242–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.G. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444(7117), 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, F. and Tsuda, K. (2010) Understanding the plant immune system. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23(12), 1531–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, B. and Krattinger, S.G. (2018) A new player in race‐specific resistance. Nat. Plants, 4(4), 197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohorn, B.D. (2016) Cell wall‐associated kinases and pectin perception. J. Exp. Bot. 67(2), 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourelis, J. and Van Der Hoorn, R.A.L. (2018) Defended to the nines: 25 years of resistance gene cloning identifies nine mechanisms for R protein function. Plant Cell, 30(2), 285–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski, M. , Schein, J. , Birol, I. , Connors, J. , Gascoyne, R. , Horsman, D. , Jones, S.J. and Marra, M.A. (2009) Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19(9), 1639–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkan, N.J. , Lydiate, D.J. , Parkin, I.A.P. , Nelson, M.N. , Epp, D.J. , Cowling, W.A. , Rimmer, S.R. and Borhan, M.H. (2013) The Brassica napus blackleg resistance gene LepR3 encodes a receptor‐like protein triggered by the Leptosphaeria maculans effector AVRLM1. New Phytol. 197(2), 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkan, N.J. , Ma, L. and Borhan, M.H. (2015) The Brassica napus receptor‐like protein RLM2 is encoded by a second allele of the LepR3/Rlm2 blackleg resistance locus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13(7), 983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkan, N.J. , Yu, F. , Lydiate, D.J. , Rimmer, S.R. and Borhan, M.H. (2016) Single R gene introgression lines for accurate dissection of the Brassica ‐ Leptosphaeria pathosystem. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebrand, T.W.H. , van den Burg, H.A. and Joosten, M.H.A.J. (2014) Two for all: Receptor‐associated kinases SOBIR1 and BAK1. Trends Plant Sci. 19(2), 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L. and Borhan, M.H. (2015) The receptor‐like kinase SOBIR1 interacts with Brassica napus LepR3 and is required for Leptosphaeria maculans AvrLm1‐triggered immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L. , Djavaheri, M. , Wang, H. , Larkan, N.J. , Haddadi, P. , Beynon, E. , Gropp, G. and Borhan, M.H. (2018). Leptosphaeria maculans effector protein AvrLm1 modulates plant immunity by enhancing MAP kinase 9 phosphorylation. iScience, 3, 177–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer, R. , Wilde, K. , Mayerhofer, M. , Lydiate, D. , Bansal, V.K. , Good, A.G. and Parkin, I.A.P. (2005) Complexities of chromosome landing in a highly duplicated genome: Toward map‐based cloning of a gene controlling blackleg resistance in Brassica napus . Genetics, 171(4), 1977–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, S. , Ruzvidzo, O. , Morse, M. , Donaldson, L. , Kwezi, L. and Gehring, C. (2010) The Arabidopsis wall associated kinase‐like 10 gene encodes a functional guanylyl cyclase and is co‐expressed with pathogen defense related genes. PLoS One, 5(1), e8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, I.A.P. , Gulden, S.M. , Sharpe, A.G. , Lukens, L. , Trick, M. , Osborn, T.C. and Lydiate, D.J. (2005) Segmental structure of the Brassica napus genome based on comparative analysis with Arabidopsis thaliana . Genetics, 171(2), 765–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlange, F. , Daverdin, G. , Fudal, I. , Kuhn, M.‐L. , Balesdent, M.‐H. , Blaise, F. , Grezes‐Besset, B. and Rouxel, T. (2009) Leptosphaeria maculans avirulence gene AvrLm4‐7 confers a dual recognition specificity by the Rlm4 and Rlm7 resistance genes of oilseed rape, and circumvents Rlm4‐mediated recognition through a single amino acid change. Mol. Microbiol. 71(4), 851–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plissonneau, C. , Daverdin, G. , Ollivier, B. , Blaise, F. , Degrave, A. , Fudal, I. , Rouxel, T. and Balesdent, M.‐H. (2016) A game of hide and seek between avirulence genes AvrLm4‐7 and AvrLm3 in Leptosphaeria maculans . New Phytol. 209(4), 1613–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, A.R. and Hall, I.M. (2010) BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics, 26(6), 841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Moreno, L. , Ebert, M.K. , Bolton, M.D. and Thomma, B.P.H.J. (2018) Tools of the crook‐ infection strategies of fungal plant pathogens. Plant J. 93(4), 664–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saintenac, C. , Lee, W.S. , Cambon, F. et al . (2018) Wheat receptor‐kinase‐like protein Stb6 controls gene‐for‐gene resistance to fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici . Nat. Genet. 50(3), 368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu, S.H. and Bleecker, A.B. (2001) Receptor‐like kinases from Arabidopsis form a monophyletic gene family related to animal receptor kinases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98(19), 10763–10768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz, H.U. , Mitrousia, G.K. , de Wit, P.J.G.M. and Fitt, B.D.L. (2014) Effector‐triggered defence against apoplastic fungal pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 19(8), 491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J. , Nürnberger, T. and Joosten, M.H.A.J. (2011) Of PAMPs and effectors: the blurred PTI‐ETI dichotomy. Plant Cell, 23(1), 4–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burgh, A.M. and Joosten, M.H.A.J. (2019) Plant immunity: thinking outside and inside the box. Trends Plant Sci. 24, 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verica, J.A. and He, Z.H. (2002) The cell wall‐associated kinase (WAK) and WAK‐like kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 129(2), 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Wang, H. , Wang, J. et al . (2011) The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa . Nat. Genet. 43(10), 1035–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensel, A. , Karthikeyan, A.S. , Wilks, C. et al . (2011) The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): Improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(D1), D1202–D1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Deng, F. and Ramonell, K.M. (2012) Receptor‐like kinases and receptor‐like proteins: keys to pathogen recognition and defense signaling in plant innate immunity. Front. Biol. 7(2), 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. , Dodds, P.N. and Bernoux, M. (2017) What do we know about NOD‐like receptors in plant immunity? Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 55, 205–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z. , Marcel, T.C. , Hartmann, F.E. et al . (2017) A small secreted protein in Zymoseptoria tritici is responsible for avirulence on wheat cultivars carrying the Stb6 resistance gene. New Phytol. 214(2), 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowski, P.A. , Kaczmarek, M. , Babula, D. and Sadowski, J. (2006) Genome evolution in Arabidopsis/Brassica: Conservation and divergence of ancient rearranged segments and their breakpoints. Plant J. 47(1), 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel, C. (2014) Plant pattern‐recognition receptors. Trends Immunol. 35(7), 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Phenotypic reaction of B. napus lines and T1 transgenics to AvrLm5‐9 transgenic L. maculans isolate.

Figure S2. Protein sequence alignment for resistant and susceptible proteins.

Figure S3. Expression of B. napus SOBIR1 and BAK1 homologues.

Figure S4. Transgenic confirmation of Rlm9 phenotype in B. napus varieties.

Figure S5. Yeast two‐hybrid assay.

Figure S6A . Multiple sequence alignment and dendrogram for GUB_WAK domains.

Table S1. Rlm9 interval of the B. napus genome (Darmor‐bzh).

Table S2. Insert copy number and phenotypic reaction for Rlm9 transgenic B. napus lines.

Table S3. Transgenic Avr–Rlm9 interactions.

Table S4. Rlm9 PCR and pathological interactions for B. napus lines.

Table S5. B. napus WAKL and WAK protein matches.

Table S6. PCR primers.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data can be found within the manuscript and its supporting materials.