Abstract

Introduction

Patients with haematological malignancies may not be receiving appropriate referrals to palliative care and continuing to have treatments in the end stages of their disease. This systematic review of qualitative research aimed to synthesise healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) views and experiences of palliative care for adult patients with a haematologic malignancy.

Methods

A systematic search strategy was undertaken across eight databases. Thomas and Harden's approach to thematic analysis guided synthesis on the seventeen included studies. GRADE‐GRADEQual guided assessment of confidence in the synthesised findings.

Results

Three analytic themes were identified: (a) “Maybe we can pull another ‘rabbit out of the hat’,” represents doctors’ therapeutic optimism, (b) “To tell or not to tell?” explores doctors’ decision‐making around introducing palliative care, and (c) “Hospice, home or hospital?” describes HCPs concerns about challenges faced by haematology patients at end of life in terms of transfusion support and risk of catastrophic bleeds.

Conclusion

Haematologists value the importance of integrated palliative care but prefer the term “supportive care.” Early integration of supportive care alongside active curative treatment should be the model of choice in haematology settings in order to achieve the best outcomes and improved quality of life.

Keywords: cancer, haematology, healthcare professional, palliative care, qualitative, qualitative evidence synthesis, review

1. INTRODUCTION

Haematological malignancies are a large collection of heterogeneous blood cancers with huge variation in presentation, treatment and prognosis, ranging from acute leukaemias, high‐grade lymphoma and aggressive multiple myeloma to more indolent neoplasms such as low‐grade lymphomas and myelodysplastic syndromes (Ruiz et al., 2018). Intensive chemotherapy is used in the management of many haematological cancers, and this can result in severe and debilitating adverse events (Button, Bolton, et al., 2019a). Patients with haematological malignancies are unique in terms of the challenges they face at end of life (EOL) with bone marrow insufficiency, infections and transfusion requirements.

Palliative care, also referred to as “supportive care,” is focused on good quality of life (QoL) and is defined as treatment, care and support for people with a life‐limiting illness and their family and friends (Marie Curie, 2018). There is substantial evidence to suggest that patients with haematological malignancies are not receiving appropriate or timely referrals to palliative care (Button, Gavin, & Keogh, 2014; Cheng, Sham, Chan, Li, & Au, 2015; Earle et al., 2008; Howell et al., 2010; Joske & McGrath, 2007; Moreno‐Alonso et al., 2018; Odejide, Cronin, Earle, Tulsky, & Abel, 2017). Moreover, for those who do receive palliative care, it tends to happen later than those with non‐haematological malignancy (Manitta, Philip, & Cole‐Sinclair, 2010; Moreno‐Alonso et al., 2018). The reasons for this are many, including the unpredictable illness trajectory associated with haematological malignancies and a persistent view among haematologists associating palliative care with EOL (Le Blanc, 2016), and their belief that home hospice is not suitable due to lack of transfusion support for their patients (Odejide et al., 2017). Moreover, haematologists often prefer to manage palliative care themselves (LeBlanc et al., 2015; Wright & Forbes, 2017) and also delay EOL care because of unrealistic expectations that treatment may be beneficial (Button et al., 2014; Leung et al., 2012; Odejide, Salas Coronado, Watts, Wright, & Abel, 2014). Nevertheless, there is growing evidence of haematologists’ support for integrated palliative care (Cormican & Dowling, 2016; Wright & Forbes, 2017), and recent evidence illustrates the benefit of early palliative care on patients’ QoL (El‐Jawahri et al., 2016; Ofran et al., 2019).

Salvage therapies see many patients continuing to have treatments in the later stages of the disease, which often gives rise to false hope and denial from both patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs, Howell et al., 2010). Most haematology patients face ending life amid escalating technology in the curative system without access to palliative care, and they are more likely to die in hospital following escalation of treatments (Manitta et al., 2010). In one study, intensive chemotherapy with a probable curative intent was given to 69 patients (40.1% of the total sample) in their last seven days before death (Brück et al., 2012). However, it must be noted that the majority of patients in this latter study had a diagnosis of acute leukaemia. In another more recent study, patients who were given chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life were more likely to die in hospital (Soares, Gomes, & Japiassu, 2019). However, actively treating haematology patients in a context where there is no planning for end‐of‐end life causes distress for nurses (Grech, Depares, & Scerri, 2018). Nurses’ concerns on the deterioration of haematology patients are often ignored until patients are in a terminal phase of their disease (Button et al., 2014). Moreover, haematology nurses describe the challenge to providing a good death when patients are on active treatment in a culture of cure, but with the possibility of these patients dying (De Araújo, Da Silva, & Francisco, 2004).

A scoping search to “give a snapshot of the volume and type of evidence available for synthesis” (Boland, Cherry, & Dickson, 2014, p. 21) was undertaken. While this scoping search did not reveal any qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) on this topic, we did find a recent integrative review focused on palliative care in patients with haematological malignancies, which included 25 qualitative studies (out of a total of 99 studies) (Moreno‐Alonso et al., 2018). However, only papers published up to June 2015 were included, and since then, there has been additional qualitative studies published on this topic (e.g., Grech et al., 2018; McCaughan et al., 2019; Morikawa, Shirai, Ochiai, & Miyagawa, 2016; Prod’homme et al., 2018; Wright & Forbes, 2017). QES provides a deep view of a topic and can offer guidance to clinicians, and inform policy and practice (Thorne, 2009). The synthesis of individual qualitative studies presents themes across time and geographical distance, which serve to inform both practice and education. Moreover, a comprehensive synthesis of qualitative research can uncover any areas that require further research (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2010; Tong, Palmer, Craig, & Strippoli, 2016).

The aim of this QES was to identify and synthesise all available qualitative research relating to HCPs views and experiences of palliative care for adult patients with a haematologic malignancy.

2. METHODS

We use the RETREAT criteria‐based review to guide our chosen data synthesis method. RETREAT was devised by Booth et al. (2018) to help researchers choose the most suitable approach and includes the following criteria to guide researchers: Review question–Epistemology–Time/Timescale–Resources–Expertise–Audience and purpose–Type of data. Using these criteria, we adopted Thomas and Harden’s (2008) thematic synthesis approach. Thematic synthesis moves beyond description to create analytical and therefore more interpretive themes (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The ENTREQ statement “Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research” was followed (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, 2012).

2.1. Search strategy

Conducting a search systematically is important as it helps to both reduce bias and also ensures that “a comprehensive body of knowledge” on the chosen topic is identified (Booth, 2016, p. 2). Using the SPICE framework (setting, population, intervention, comparison, evaluation) (Stern, Jordan, & McArthur, 2014), we identified the main concepts and search terms for the research question to guide the search (Table 1). Following this, a “pearl‐growing” approach was adopted to scope out key papers and identify relevant keywords (Booth, 2016, p. 115). We also searched for any topically related qualitative studies and systematic reviews. We created a table to systematically document relevant terms, which also allowed for easier translation across the different databases. Text mining software such as PubReMiner, Yale MeSH Analyzer and Carrot2 were also employed to identify phrases, keywords and medical subject headings. Six databases were systematically searched: EBSCO CINAHL, EMBASE (Embase.com), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycINFO, Web of Science and ProQuest. No date limit was applied to ensure that a complete body of literature was retrieved by the search. In order to retrieve qualitative studies, we explored the ISSG Search Filter Resource (ISSG, n.d.) for guidance on searching for qualitative research. Traditional subject searching of the databases may miss key pieces of information due to the indexing of the term “qualitative,” and it is essential to use alternative methods of searching (Papaioannou, Sutton, Carroll, Booth, & Wong, 2010). Therefore, we undertook supplementary searching of grey literature, theses, reference list checking of key papers, hand searching, following citations in Scopus and Web of Science as well as searching Google Scholar as a control check. Moreover, to ensure rigour and quality control we used the CADTH (McGowan et al., 2016, p. 46) peer review checklist for search strategies, which “can improve the quality and comprehensiveness of the search and reduce errors.”

TABLE 1.

Search strategy: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and epub ahead of print, in‐process and other non‐indexed citations, daily and versions(R)

| # | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp health personnel/ |

| 2 | exp Patient Care Team/ |

| 3 | exp Health Occupations/ |

| 4 | (allied health or doctor* or nurs* or physician* or nursing staff or nursing personnel or therapist* or physiotherapist* or physician* or medical resident* or provider* or practitioner* or GP or skilled health provider* or skilled care or social worker* or intensive care nurs* or critical care nurs* or oncology nurs* or Palliative care team).tw,kf. |

| 5 | ((Nursing adj3 (staff or personnel)) or ((health* or medical) adj3 (staff or professional* or personnel or worker* or workforce))).mp. |

| 6 | or/1−5 |

| 7 | exp Palliative Care/ |

| 8 | Terminal Care/ |

| 9 | exp “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”/ |

| 10 | exp Advance Care Planning/ |

| 11 | exp Terminally Ill/ |

| 12 | (end of life or palliat* or palliat* care or terminal care* or palliat* therap* or EoLC or hospice care).tw,kf. |

| 13 | ((dying adj3 (care or close or comfort or relief or stage)) or (terminal adj3 (care* or ill* or stage or disease)) or (Hospice adj3 (care or program*)) or (bereavement adj3 (support or care))).mp. |

| 14 | or/7−13 |

| 15 | exp Hematologic Neoplasms/ |

| 16 | exp Lymphoma/ |

| 17 | exp Leukemia/ |

| 18 | exp Multiple Myeloma/ |

| 19 | (Leuk?emia or Acute myeloid leuk?emia or acute myelogenous leuk?emia or acute myeloblastic leuk?emia or acute granulocytic leuk?emia or acute non‐lymphocytic leuk?emia or Chronic lymphocytic leuk?emia or Chronic myeloid leuk?emia or chronic myelogenous leuk?emia or Hairy cell leuk?emia or Myelodysplastic syndrome* or MDS or AML or CLL or CML or blood cancer or Myeloma* or Multiple Myeloma or Myelomatosis or myeloproliferat* or myelofibrosis or plasmacytoma* or myeloproliferative neoplasm or myeloid Metaplasia or Hodgkin* or non‐hodgkin* or burkitt* lymph* or lymphosarcoma*).tw,kf. |

| 20 | ((h?ematolog* adj1 neoplas*) or (h?ematolog* adj1 malignan*) or (h?ematolog* adj1 (disease* or disorder* or condition)) or (bone marrow adj1 (neoplasm* or cancer*))).mp. |

| 21 | or/15−20 |

| 22 | 6 and 14 and 21 |

2.2. Screening and study selection

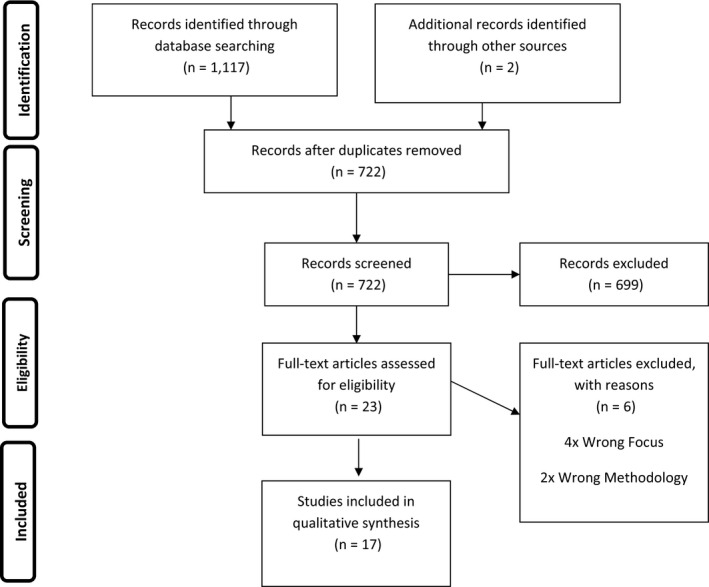

The initial search retrieved 1,117 references. A subsequent quality control check of Google Scholar identified 2 additional studies. All search results were exported into the reference management software, EndNote X9.

Following removal of duplicates, the title and abstract of all 722 remaining papers were screened blindly by two reviewers (MD and PF) in Rayyan, a software for systematic reviews (Olofsson et al., 2017; Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, 2016). Papers were included if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Studies in the English language only.

Qualitative and/or mixed method studies with primary data to include personal experiences or perceptions, interviews, direct observation, focus groups, participation action research, grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, content analysis, thematic analysis, narrative analysis, generic qualitative studies.

Studies involving adult patients ≥18 years.

Studies to include any healthcare professionals’ experiences (doctors, nurses, social workers, physiotherapists).

Studies exploring healthcare professionals’ experiences of and views on palliative care for patients with a haematology malignancy.

Twenty‐three papers meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for full‐text review by the first and second authors. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and six studies were excluded from the review (Figure 1 and Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of article selection through PRISMA (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009)

TABLE 2.

Study characteristics

| # | Author | Year | Country | Design/method | Sample and sampling method | Analysis | Study focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cormican and Dowling | 2016 | Ireland | Descriptive qualitative/semi‐structured individual interviews with patients and focus group interviews (n = 3) with HCPs | Purposive sample | Thematic analysis | To explore the experiences of individuals living with relapsed myeloma and the views of HCPs managing their care |

| 8 patients with relapsed myeloma | |||||||

| 17 healthcare professionals * (consultant haematologists n = 4; specialist registrars n = 2; oncology–haematology nurses n = 6; clinical nurse specialists in haematology n = 4; advanced nurse practitioner haematology n = 1). (*data extracted from HCP population only) | |||||||

| 2 | Dalgaard et al. | 2010 | Denmark | Single‐site, grounded theory approach/fieldwork involving participant observation and interviews with patients, relatives, doctors and nurses | Focus group interviews (n = 4) | Grounded theory approach | To describe the significance of a theme identified from the main study “the status report: palliative care project.” The theme focused on the identifying and clarifying transitions in incurable illness trajectories |

| Focus group interviews with nurses and doctors | Staff at one haematology department: doctors n = 9; ward nurses n = 10; outpatient nurses n = 9 | ||||||

| 3 | Gerlach et al. | 2019 | Germany | Critical realism/semi‐structured interviews | Purposive sampling | Thematic analysis using framework approach | To explore experiences, views and perceptions of haematooncologists on the use of the “Surprise” Question in the haematooncology outpatients’ clinics of a university hospital. The “Surprise” Question had been previously integrated into daily use in the clinics as part of a quantitative study |

| Haematologic oncologists, n = 9 | |||||||

| 4 | Grech et al. | 2018 | Malta | Hermeneutic phenomenological/semi‐structured in‐depth interviews | Purposive sample | Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) | To explore nurses’ experiences of providing end‐of‐life care to patients with haematologic malignancies |

| 5 nurses working in a haematology unit in an acute general hospital | |||||||

| 5 | Le Blanc et al. | 2015 | USA | Multi‐site mixed method/survey and in‐depth interviews | Random sample | Constant comparative approach | To understand and contrast perceptions of palliative care referrals among haematologic and solid tumour oncologists |

| Practicing oncologists from three sites. (n = 43 solid tumour oncologists and n = 23 haematologic oncologists* (*data extracted from haematologic oncologists only) | |||||||

| 6 | Mc Caughan et al. | 2018a | UK | Qualitative descriptive/semi‐structured in‐depth interviews | Purposive and snowball sampling | Inductive thematic analysis | To explore the experiences of clinicians and relatives to determine why hospital deaths predominate in people with a haematological malignancy |

| 45 clinicians involved in the delivery of end‐of‐life care to patients with a haematological malignancy: haematologists (n = 9); haematology nurses (n = 8); palliative care/hospice doctors (n = 6); palliative care nurses (n = 14); general practitioners (GPs) (n = 8); relatives (n = 10)*. (*data extracted from HCP population only) | |||||||

| 7 | Mc Caughan et al. | 2018b | UK | As per McCaughan et al., 2018a above | Purposive sample | Thematic analysis using the “Framework” method | To determine palliative care practitioners’ perspectives regarding the barriers and facilitators influencing haematology patient referrals to specialist palliative care |

| Palliative care clinicians n = 20 (palliative care/hospice doctors (n = 6); palliative care nurses (n = 14) | |||||||

| 8 | Mc Caughan et al. | 2019 | UK | As per McCaughan et al., 2018a above | Purposive sample | Thematic content analysis | To explore haematology nurses' perspectives of their patients’ places of care and death |

| Haematology nurses (n = 8) | |||||||

| 9 | McGrath and Holewa | 2006 | Australia | Descriptive phenomenology/open‐ended interviews | Purposive sample | Thematic analysis managed by QSR NUD* IST | To develop a best practice model for end‐of‐life care by exploring HC professionals’ experiences of terminal care for patients with haematological neoplasms. The findings presented were from the five nursing codes informing the theme “haematology patients do die in the curative system” |

| HC professionals across specialist treatment centres. This study reports of the experiences of acute care nurses (n = 19) only. As part of the main study, others interviewed included: palliative care nurses (n = 4); haematologists (n = 15); palliative care physicians (n = 7); general practitioners (n = 2); allied health professionals (n = 6); leukaemia foundation support workers (n = 10); hospice staff (n = 4) | |||||||

| 10 | McGrath and Holewa | 2007a | Australia | As per McGrath and Holewa 2006 above | Purposive sample | To develop a best practice model for end‐of‐life care by exploring HC professionals’ experiences of terminal care for patients with haematological neoplasms. The findings presented were from the five nursing codes informing the theme “special considerations of haematology patients” | |

| This study reports of the experiences of acute care nurses (n = 19) only | |||||||

| 11 | McGrath and Holewa | 2007b | Australia | As per McGrath and Holewa 2006 above | Purposive sample | To present a model for end‐of‐life care in haematology that has been developed from nursing insights | |

| This study reports of the experiences of acute care nurses (n = 19) and palliative care nurses (n = 4) only | |||||||

| 12 | McGrath and Leahy | 2009 | Australia | As per McGrath and Holewa 2006 above | Purposive sample. This study reports on the views of haematology nurses (n = 17), palliative care nurses (n = 4) and haematologists (n = 15) | To develop a best practice model for end‐of‐life care by exploring HC professionals’ experiences of terminal care for patients with haematological neoplasms. The findings presented were from the theme of catastrophic bleeds during EOL in haematology | |

| 13 | Mollica et al. | 2018 | USA | Grounded theory/semi‐structured interviews | Purposive sample | Team‐based coding method managed using NVivo software | To understand the diverse perspectives of multidisciplinary oncology care providers of palliative care for cancer patients enrolled on clinical trials |

| Multidisciplinary cancer clinical trials (phases 1 and 11), team members (n = 19), including key informants and additional HC staff caring for haematologic and prostate cancer patients | |||||||

| 14 | Morikawa et al. | 2016 | Japan | Qualitative descriptive/semi‐structured in‐depth interviews | Snowball sampling | Content analysis | To assess haematologists and palliative care specialists’ perception of the roles of the hospital‐based palliative care team and the barriers to collaboration between haematologists and palliative care teams on relapse or refractory leukaemia and malignant lymphoma patients’ care |

| Haematologists (n = 11) and palliative care specialists (n = 10) | |||||||

| 15 | Odejide et al. | 2014 | USA | Qualitative descriptive/focus group interviews (n = 4) | Purposeful sampling | Thematic analysis | To explore haematologic oncologists’ perspectives and decision‐making processes regarding end‐of‐life care for people with blood cancers |

| Haematologic oncologists (n = 20) | |||||||

| 16 | Prod'homme et al. | 2018 | France and Belgium | Grounded theory/individual in‐depth interviews | Purposive sampling | Grounded theory approach managed with NVivo 11 software | To determine haematologists’ barriers to end‐of‐life discussions when potentially fatal haematological malignancies recur |

| Haematologists (n = 10) | |||||||

| 17 | Wright and Forbes | 2017 | UK | Qualitative descriptive | Purposive sampling | Grounded theory approach (constant comparison) | To explore the views and perceptions of haematologists towards palliative care |

| Trainee and consultant haematologists (n = 8) |

2.3. Quality assessment

Assessment of methodological limitations was undertaken by the first and third authors in tandem with data extraction using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2017) (Table 3). Furthermore, in order to determine overall confidence in the study findings, the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative (CERQual) research approach was used, guided by each study's methodological limitations, relevance, coherence and adequacy (Lewin et al., 2018). An estimation of high and moderate confidence for the findings was reached (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

CASP (2017) (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) quality assessment table of included studies

| S | Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Is there a clear statement of findings? | How valuable is the research? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cormican and Dowling (2016) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 2 | Dalgaard et al. (2010) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 3 | Gerlach et al. (2019) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4 | Grech et al. (2018) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 5 | LeBlanc et al. (2015) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 6 | McCaughan et al. (2018a) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 7 | McCaughan et al. (2018b) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 8 | McCaughan et al. (2019) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 9, | McGrath and Holewa (2006) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 10 | McGrath and Holewa (2007a) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 11 | McGrath and Holewa (2007b) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 12 | McGrath and Leahy (2009) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 13 | Mollica et al. (2018) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 14 | Morikawa et al. (2016) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 15 | Odejide et al. (2014) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 16 | Prod'homme et al. (2018) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 17 | Wright and Forbes (2017) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

TABLE 4.

Analytic themes and subthemes and confidence in the evidence (Lewin et al., 2018)

| Review finding (analytic themes and subthemes) | Supporting quote | Studies contributing to review findings | Confidence in evidence and explanation of CERQual judgement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maybe we can pull another “rabbit out of the hat” | There is an awful lot of uncertainty around their care [patients with relapsed myeloma] (Nurse: Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 54) | 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 15, 17 | High confidence |

| We're in an area with almost no evidence. How treatment works out is highly individual. Let's say we've two identical’ patients with a relapse of highly malignant lymphoma‐ the one patient may be very chemo‐sensitive and curable, while the other is basically refractory. (Doctor: Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89) | |||

| Unpredictable disease | Eight studies with no concerns about methodological limitations | ||

| Blood cancers are different from solid cancers in terms of their unpredictable nature and chance of cure | … either they are cured within six months and the live maybe 30 more years, or they don't survive the next two weeks (Haemato‐oncologist, Gerlach et al., 2019, p. 535) | Seven studies with no concerns about coherence, relevance and adequacy | |

| I do think their disease trajectory makes it more difficult to, eh, actually predict when they're going to start deteriorating, compared to other cancers (GP, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 79) | One study with minor concerns over coherence and adequacy (17) | ||

| I think with oncology patients … it's a gradual decline and they kind of … decide when enough is enough … but haematology is really fast, in that they become unwell and … the time they spend when it would be like their EOL period, you spend trying to save them, and then all of a sudden … they die really quickly. (Haematology nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 7) | |||

| I don't think it's quite as easy to predict a lot of the trajectories as it is for some of the other malignancies … it's not that simple for the haematologist. (Specialist palliative care doctor: McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 4) | |||

| There's a very definite split between haematology and oncology … oncology moves on … to palliative care services maybe earlier than haematology … With some of the haematology patients that doesn't happen until the very last hours or very last days of life … (Haematology nurse, McCaughan et al., 2019, p. 74) | |||

| I mean, our patients’ conditions can change really quickly (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2007a, p. 167) | |||

| I guess it's because in that group, in the acute “leuk” group, the disease is that aggressive and fast forming. Like they've only been sick for a couple of days or maybe a week and then they're super sick‐ like you feel like you will see them drop dead. (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2007a, p. 167) | |||

| EOL is such a tricky thing in our field; it can change momentarily. I had a patient who had a transplant, he was doing well, but then he relapsed, the disease took off … and he died within a few days … he just had a transplant! It's unpredictable. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398) | |||

| Patients with heme malignancies are generally completely different from patients with solid tumours. A lot of these measures, like no chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life, I would expect them to be different based on the fact that chemotherapy for heme malignancies is generally more effective than chemotherapy for solid tumours; these parameters‐are they applicable to our patient population? (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e403) | |||

| I sometimes joke that haematology is intensive care and oncology is palliative care. And um, obviously that's not true but um … [haematology] is very intensitivist … and if our mind‐set is like that with the first 12 patients on the ward then, you know, it's quite difficult then to … switch. (Haematologist, Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 41) | |||

| Therapeutic optimism | When they [doctors] discontinue treatment there are usually only a few days left. (Nurse, Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 90) | ||

| Haematology doctors display therapeutic optimism in their focus on finding an effective treatment. They will try “latch ditch” treatments to pursue a cure, which often results in patients dying while being actively treated. Some patients are also driven by therapeutic optimism | We know colleagues who never say no [to further treatment]. We have to admit that [not being able to stop treatment] only helps the doctor and can be a defence to avoid engaging in a difficult conversation. (Doctor: Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89) | 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15 | High confidence |

| The trouble is not knowing in advance what might be achieved and what might not … that's quite tricky. (Haematologist, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80) | Seven studies with no concerns about coherence, relevance, adequacy and methodological limitations | ||

| Last ditch treatment (to) pull a patient back from the brink. (Haematologist: McCaughan et al., 2018b, page 3) | |||

| I think haematology wants to keep patients going as long as possible and they don't want to break that bad news. (Palliative care nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80) | |||

| Yeah. You know it's all … cure and not (palliative care) … (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2006, p. 297) | |||

| [There is] a genuine optimism by doctors that they are seeing enough incremental. A patient today, about six weeks ago had pretty well said that there was no hope; was given like less than 5% he was not suitable for transplant. Whilst we were making all these adjustments to his care … his counts returned then all of a sudden the whole scenario changed. (McGrath & Holewa, 2007a, p. 168) | |||

| Patients with haematological malignancies tend to get treated and treated and treated. (Specialist palliative nurse; McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 4) | |||

| Even when they're [patients] on the brink of really being extremely poorly, some weird and wonderful medicines can actually bring them back. (Specialist palliative doctor, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 4) | |||

| You're trying to tell the primary team … a patient said that they want to change their plan … decrease their care, but the primary team is not ready to hear that, yet, or not wanting to hear that, yet, because they had high hopes or plans … (Palliative care Doctor: Mollica et al., 2018, p. 616) | |||

| … in some of these high‐risk [hematologic] patients, you actually can't say that they have no chance of cure. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e403) | |||

| … we live on the tail, this 5% to 10% tail (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398) | |||

| … these are diseases where there are a lot of active drugs, unlike a lot of advanced solid tumours … you are always thinking you can pull some rabbit out the hat; you tend to think that something is going to work. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398) | |||

| You get invested in your patients. We've known a lot of these patients for a long time and we've seen them more than their primary care doctor, and you start of have an unrealistic belief in your ability to control the disease. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e403) | |||

| Nurses’ distress | |||

| Nurses feel distress caring for patients who often die while being actively treated | There was a patient who, even with having a really detailed conversation with a consultant and his family about the poor, poor prognostic outcome of maybe a fourth line chemotherapy … the patient want to, to take it (Specialist Palliative care nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 4) | 1, 2, 4, 6, 9 | Moderate confidence |

| They just want to keep living. You know they don't want to give up. Their QoL may be crap but they just want to keep going (Nurse: Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55) | Five studies with no concerns about relevance and methodological limitations | ||

| You would wonder when the line would be drawn to say you need to spend time with your family and friends … (Nurse, Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55 | Three studies with moderate concerns over coherence and adequacy (1, 6, 9) | ||

| “when they (doctors) discontinue treatment there are usually only a few days left” (Dalgaard, 2010, p. 90) | |||

| If he dies on another ward, it really shocks me, and sometimes I cry … (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 240) | |||

| Is there any need to intubate this patient who is nearing the end? Why do we need to expose him to such an ordeal? Is there really a need for such an ordeal? (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 240) | |||

| Why don't they leave him [patient] to die in piece … he was not responding … to chemotherapy, cycle after cycle … (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 239) | |||

| … the cry of the patient penetrates your heart … it is so distressing (Nurse: Grech et al 2016, p. 240) | |||

| The patient should be left alone without having to do many investigations and blood taking and the other useless treatments … he can then die quietly, with dignity … if we let them … (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 239) | |||

| … it does not even occur to the consultants that they can refer to palliative care; they do not even think about it … no referrals … here they go on till the very end … to cure … it's useless … (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 241) | |||

| Some consultants treat, treat, treat. (Palliative nurse; McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80) | |||

| To tell or not to tell? | It's difficult when you're with a patient that's dying and then you've got to walk out and you've got to walk in the next one and say, “Hi, how are you?”. It's hard especially when that person dies and you've still got the rest of your patients to look after. (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2006. p. 299) | ||

| Age matters | High confidence | ||

| The patient's age is considered when deciding to continue with treatment or introduce palliative care | It's all about‐how can I word it‐giving false signals. We are giving them all this treatment, but we aren't actually telling them “this could be the end of the road”. They are actually going to die, probably. (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2006, p. 298) | 3, 4, 6, 15, 16 | Five studies with no concerns about methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy or relevance |

| Well, with patients who are in close contact, just those patients, who are perhaps only a bit older than me, then it is challenging to allow for myself the “Surprise” question, and to be aware of it. (Haemato‐Oncologist, Gerlach et al., 2019, p. 537) | |||

| When they are young, and if there may be some hope, one should go on fighting as they should have a life ahead of them … (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 241) | |||

| Age plays such a big role; if you've got somebody who is 25 years old, you are going to go down blazing typically, they may get seven or eight lines of chemotherapy because they can take it for a while. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398) | |||

| This guy, 1m85, 100 kg, great shape. Recur, OK, but I didn't talk about dying. But if you've got a 90‐year‐old patient with acute leukaemia, it's not the same thing! And they know it. But for young patients, no! ((Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025) | |||

| … the thrust of AML is completely wrong, if the patient is over 60 or 70 you are never going to cure them. Taking a more palliative, QoL approach would probably be better. (Haematologist, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80). | |||

| Don't want patients to lose hope | It's difficult when there's a discrepancy between what the patient knows and believes and our knowledge and experience’ (Doctor: Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89) | 2, 7, 9, 16 | Moderate confidence |

| Nurses and doctors were concerned that talking to patients about palliative care would result in the patient losing hope | The patients invest a lot of hope in the treatment. We mustn't undermine people's hope. (Nurse: Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89) | Four studies with no concerns about methodological limitations or relevance and moderate concerns about adequacy and coherence | |

| You can't [introduce palliative care] because you would talk away their hope. (Nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2007b, p. 82) | |||

| With a lot of haematological malignancies a percentage of people can be cured … so [end of life care is] not necessarily something you want to ask at the beginning when you're embarking on what might be curative treatment, so it's quite difficult picking the right time to have those conversations. (Specialist palliative care doctor; McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5) | |||

| If the patient doesn't ask, “am I going to die, when I am going to die”. I’m not going to force the truth down their throat. (Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025) | |||

| I never bring up the subject [end‐of‐life] myself because the patient might think “but if she doesn't really in it [treatment] … if she tells me it might not work” (Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1024) | |||

| It's not my job to down our patients. (Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025) | |||

| Palliative care means EOL | We should try to involve palliative care as early as possible to create an opportunity for palliative care to take over trust and understanding with the patient because … my understanding at the moment is that in Ireland many patients think of palliative care as EOL rather than management of complications, side effects or other confinements … (Haematologist: Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55) | 1, 5, 7, 9, 13, 16, 17 | High confidence |

| HCPs believe that patients associate palliative care with EOL | There is a perception [among myeloma patients] that palliative care is the end. (Nurse: Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55) | Seven studies with no concerns about methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy or relevance | |

| When I think of palliative care, I’m thinking end‐of‐life hospice and the patient will pass (Nurse: Mollica et al., 2018, p. 618) | |||

| Sometimes people will say … “The death team” … that it means comfort measures only, end‐of‐life … it can be stigmatized a little bit where people actually think we're coming here to expedite people's death. (Palliative care doctor: Mollica et al., 2018, p. 618) | |||

| Gosh, the Macmillan nurse is here, that means I’m going to die … (Specialist palliative care nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5) | |||

| It (palliative care) comes across as a negative thing for them (haematologists) (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2006, p. 298) | |||

| When you talk about palliative care, [you're] really gonna stop any treatments. (Haematologist, LeBlanc et al., 2015, p. e234) | |||

| Patients see palliative care as “somewhere you go to die” (McCaughan et al., 2018b, p5) | |||

| They [palliative care team] do not propose a “half‐in half‐out” alternative. Either the patient accepts palliative care as an overall exclusive option, or asks palliative care team to come back later if needed. (Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025) | |||

| … I think we still think of it as EOL. (Dr H. Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 41) | |||

| I have worked for a team where a Macmillan nurse wasn't allowed on the ward round, because the consultants felt that meant that the patients might think that some of them were dying (laughs) (Dr B. Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 41) | |||

| Benchmark for transition to palliative care referral | Both the nursing and medical staff must have a deep awareness of the situation before [transition to palliative care] such a conclusion is drawn. (Doctor: Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89) | ||

| Doctors look for signs of worsening QoL as benchmarks to signal an end of treatment and transition to palliative care | If QoL is declining because of drug toxicities, cytopenias, or multiple trips to the hospital. I think that's when it's easier to start talking about EOL care. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398) | 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 16 | High confidence |

| Six studies with no concerns about methodological limitations or relevance | |||

| At some point, when … when you've talked with all your colleagues, when you know there's no drug, no treatment, nothing to propose, well … you have to do it … talk to the person. (Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025) | Four studies with no concerns about relevance adequacy and coherence (2, 5, 15, 16) | ||

| The “Surprise”‐Question was seen as a bridge for specialised palliative care “… the link to think about palliative care became stronger” Because it allows you to think, eh, or virtually assess: “How do I see the prognosis of this patient? To keep this in mind and perhaps talk about it with the patient. I think this makes sense” (Haemo‐Oncologist: Gerlach et al., 2019, p. 535) | Two studies with minor concerns about adequacy and coherence (2, 3) | ||

| The sort of thing we look at is, how many treatments that they have had, when was their last treatment. So they can have had their three cycles of high dose chemotherapy, and they relapsed within how much time. Relapse is even harder to get them into remission, and when some are in remission it will come back even sooner. But I also look at how they are going and the increase in symptoms in the patients, and just that generally look and feel. (Acute care nurse: McGrath and Holowea, 2007a, p. 169) | |||

| How I usually come to the decision of a palliative care referral is: it can either be for patients for whom active oncologic treatment isn't really indicated anymore, either because they've sort of failed all available treatments or they're becoming progressively more symptomatic and their performance status is declining and/or they just don't want to pursue treatment. (Haematologist, LeBlanc et al., 2015, p. e234) | |||

| Hospice, home or hospital? | … here the tendency is for doctors to keep on hoping. When there is full metastasis, and they hesitate to start the morphine pump … you call the doctors, and no one wants to take the responsibility of initiating the morphine pump … it is as if they do not understand you (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 240) | ||

| Interprofessional voices | 4, 7, 8 | ||

| Nurses and palliative care professionals want to be heard | You give your opinion, and the doctors tell you, now we will see (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 240) | Moderate confidence | |

| It's not a face‐to‐face relationship [with haematologists] by us being removed in the hospice and in the community. (Specialist Palliative care Doctor,; McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5) | Three studies with no concerns about methodological limitations and relevance. One study with moderate concerns about coherence and adequacy (7) | ||

| Our relationship is really good … we couldn't go for a period to the ward rounds and referral started to drop off … it's about our visibility … if we're there it reminds them that actually they can ask our advice and referrals go up, when we've a high profile, referrals go up (SPC nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 7) | |||

| It's all about relationship building. We're learning about their speciality as much as they're learning about us and it's just about shared understanding I think … we have a joint clinic once a week … influencing decision making patient by patients … you're seen as more as part of the team. (SPC doctor, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 7) | Two studies with no concerns about adequacy and coherence (4, 8) | ||

| … there is nothing about the active management of a malignant disease that stops palliative care teams getting involved. (SPC doctor, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 7) | |||

| To be honest, sometimes they [haematologists] are very dismissive of us … I mean I was made to feel I want to put everyone into the LCP [Liverpool care pathway] … and I was belittled for that … (Haematology nurse; McCaughan et al., 2019, p. 73) | |||

| Don't want to abandon the patient | … sometimes when you are emotionally involved with the patient you feel you're um, abandoning them or you feel … you've failed them and all of us to some extent feel like that. Rationally you know that's not true (Dr B. Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 43) | ||

| Doctors’ close relationships with their patients contributed to their fear that discharge to hospice or home is abandoning them. They cannot help the patient anymore but fear letting go | The difficulty sometimes … is that by transferring somebody purely to palliative care, you almost feel as if you're washing your hands of them. (Haematology nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81) | 6, 8, 17 | High confidence |

| We've kind of years of quite a strong bond with our patients and I think that's the hard thing then is that when they come towards the end I think they feel they want to stay with us, (Haematology nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81) | Three studies with no concerns about methodology, relevance and coherence. Minor concerns about adequacy | ||

| The current rhetoric that the only good death is a home death is absolute nonsense … and I can see in haematology patients who have been coming in and out of the ward for years … a hospital death may be an appropriate death … and it may be done very well actually. (Haematologist; McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81) | |||

| A lot of people choose to die in hospital … they just feel safe … this is their second home. (Haematology nurse; McCaughan et al., 2019, p. 73) | |||

| … often by then the patients have built up such a relationship with us and I think if we say, “Oh well we'll no longer give you any blood products up on the ward”, they do feel like we've written them off. (Dr E. Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 43) | |||

| Hospice more suitable for solid tumours | Right now, the gap between home hospice and acute care hospitals is just too wide for our patients. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e399) | ||

| HC professionals consider that hospice is more suitable for solid cancers. Haematology patients may need transfusion support that is not available in a hospice setting. Community palliative care may not be ideal for haematology patients where strict criteria for specialist palliative care referral apply | If there were certain designated hospices that would accept patients with advanced hematologic malignancies‐that would provide maybe once a week platelet or red cell transfusions, something reasonable‐that would be the best way to do it. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e403) | ||

| Often there is no bed in the hospice, or they can't deal with transfusion needs. (Haematology consultant; McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81) | 6, 7, 9, 14, 15, 17 | High confidence | |

| I can speak from experience. I only ever had one patient in all of my years say to the doctors, “I don't want any treatment for my acute illness. I want to go home and die”. And that was an elderly nun who I guess was spiritually advanced and could face death quite easily. Every other single patient has been told with these kind of diseases that you can die from this treatment or you can go home. No one has ever said “Oh I want to go home and die” (Acute care nurse, McGrath & Holewa, 2006, p. 298) | Five studies with no concerns about methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy and relevance | ||

| I would be reluctant to be giving blood transfusion at home by myself. And I think a lot of nurses are reluctant to do that. (Nurse: McGrath & Holewa, 2007b, p. 82) | |||

| The hospice is very much, much more able now to transfuse patients, with platelets, which is much more helpful. (Specialist palliative care nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5) | |||

| [the hospice were], I would say, a little bit forceful in saying, “Well if she comes here we're not going to give her any blood products” … but it was partly their attitude about it: “Well with haematology patients you often want us to give blood products and that's not part of our end of life‐of‐life care. We don't do blood tests … that's why we don't have many haematology patients” (Dr H: Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 41) | |||

| Sometimes patients can deteriorate very quickly. Often it's difficult to get them there [hospice] then, so I think it's about … trying to broach the subject, a bit sooner. (Haematology nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 73) | |||

| There is strict criteria for referral to specialist palliative care in the community … she didn't meet the criteria (Specialist palliative care nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5) | |||

| The reality of somebody dying at home can be very, very difficult and very different from the “home sweet home” image you might have. (Haematology nurse, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80 | |||

| We really wanted him to go to the hospice as he was dying, fading away and he would have not have it … he chose to stay on the ward … he wanted to cling onto the blood tests … the reassurance he was still being watched. (Haematologist: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80) | |||

| Concerns over catastrophic bleed | Bleeding would be a big one for patients with HM … you would have to have a robust family and carers to cope with that. (Palliative doctor: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81) | ||

| HC professionals are concerned for patients going home and the risk of how a catastrophic bleed would be managed | We had a leukaemia who died from a massive bleed … completely unexpected, never expected it in a million years, gone through his treatment with no problems, was at home down in the country, umm, and then bled to death in front of his wife. Completely unexpected, we wouldn't have thought that was how he was to die. (Nurse, McGrath & Leahy, 2009, p. 529) | High confidence | |

| There should be more leeway for us to use inpatient hospice services. There has to be a little bit more coverage for that because the death for heme malignancies is more acute with the bleeding. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e403) | 6, 7, 8, 12, 15 | Five studies with no concerns about methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy and relevance | |

| The main clinical problem for haematology patients dying at home is the risk of bleeding which is a very, very unpleasant death. (Acute care nurse; McGrath & Leahy, 2009) | |||

| … somebody goes from well, to critically unwell, to dead, and you can't plan for that, they suffer some sort of complication related to chemotherapy, so bleeding, internal haemorrhage … you can't plan ahead for those (events). (Haematologist, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 79) | |||

| … a patient exsanguinating in front of his family is not very appropriate EOL care. (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e399) |

2.4. Data extraction and thematic analysis

Following Thomas and Harden’s (2008) guidance on analytic theme generation, free line‐by‐line coding of the findings of each of the seventeen studies was undertaken by the first and third authors. Findings from each study included all study participants’ verbatim accounts and the researchers’ interpretations. Subsequent discussion and cross‐checking resulted in merging of themes until the final stage of agreement on three principal analytical themes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Overview of papers

Seventeen qualitative studies were included in this review involving a total of 260 HCPs (118 haematologists, 62 acute care and haematology nurses, 23 palliative care doctors, 18 palliative care nurses and 39 “other professionals”) across five continents: Australia (n = 67), the UK (n = 51), the United States (n = 39), Denmark (n = 28), Malta (n = 28), Japan (n = 21), Ireland (n = 17), France and Belgium (n = 10) and Germany (n = 9).

3.2. Analytic themes

Three analytic themes with subthemes were synthesised from the seventeen studies (Table 4).

3.2.1. Maybe we can pull another “rabbit out of the hat”

HCPs viewed blood cancers very differently from solid cancers because of their unpredictable nature where “treatment is highly individual … one patient may be very chemo‐sensitive and curable, while the other is basically refractory” (Doctor: Dalgaard, Thorsell, & Delmar, 2010, p. 89), “either they are cured within six months and they live maybe 30 more years, or they don't survive the next two weeks” (Haemato‐oncologist: Gerlach, Goebel, Weber, Weber, & Sleeman, 2019, p. 535). There was always a chance of a cure (Cormican & Dowling, 2016; Dalgaard et al., 2010; Gerlach et al., 2019; McCaughan et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2019; McGrath & Holewa, 2007a; Odejide et al., 2014; Wright & Forbes, 2017). There was often no certainty if treatment should be curative or palliative (Dalgaard et al., 2010), and striving for a cure, doctors persisted treating patients right to the end (Dalgaard et al., 2010; Grech et al., 2018; McCaughan et al., 2018a, 2018b; McGrath & Holewa, 2006; Mollica et al., 2018; Odejide et al., 2014). This approach was driven by doctors’ therapeutic optimism (Dalgaard et al., 2010; McCaughan et al., 2018a; McGrath & Holewa, 2007a; Odejide et al., 2014), where even when patients are “on the brink of really being extremely poorly, some weird and wonderful medicines can actually bring them back” (Specialist palliative doctor: McCaughan et al., 2018b), and they (doctors) are “… always thinking you can pull some rabbit out the hat … we live on the tail, this 5% to 10% tail” (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398). However, this “therapeutic optimism” was also driven by some patients: “there was a patient who, even with having a really detailed conversation with a consultant and his family about the poor, poor prognostic outcome of maybe a fourth line chemotherapy … the patient want to, to take it” (Specialist Palliative care nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 4). “They just want to keep living. You know they don't want to give up. Their QoL may be crap but they just want to keep going” (Nurse: Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55).

Because of “lack of clear transition points and treatment late in the pathway,” patients with haematological malignancies “tend to get treated and treated and treated” (Specialist palliative nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 4), and palliative care was introduced very late resulting in patients being actively treated right to the end. Nurses questioned “when the line would be drawn” (Nurse: Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55) and if there was “any need to intubate [patients] … nearing the end? Why do we need to expose [patients] to such an ordeal?” (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 240). In addition, caring for patients who often died on active treatment caused feelings of distress among nurses (Cormican & Dowling, 2016; Dalgaard et al., 2010); Grech et al., 2018; McCaughan et al., 2018a, 2018b; McGrath & Holewa, 2006).

3.2.2. To tell or not to tell?

The patient's age was considered a factor when deciding to continue with treatment or consider discussing the introduction of palliative care (Gerlach et al., 2019; Grech et al., 2018; McCaughan et al., 2018a; Odejide et al., 2014; Prod’homme et al., 2018). “Age plays such a big role: if you've got somebody who is 25 years old, you are going to go down blazing, typically they may get seven or eight lines of chemotherapy because they can take it for a while” (Doctor, Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398) and “when they are young [they] … should go on fighting as they should have a life ahead of them” (Nurse, Grech et al., 2018, p. 241). Whereas with older patients, “… you are never going to cure them. Taking a more palliative, QoL approach would probably be better” (Haematologist, McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80).

Some nurses were concerned that they “would take away their [patients] hope” (Nurse: McGrath & Holewa, 2007b, p. 82) because “patients invest a lot of hope in the treatment [and] we mustn't undermine people's hope” (Nurse: Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89), with the introduction of palliative care. Some haematologists and palliative care doctors were also concerned not to take patients’ hope away and often reluctant to have a conversation about palliative care (Dalgaard et al., 2010; McCaughan et al., 2018b; Prod’homme et al., 2018). “I never bring up the subject [end‐of‐life] … because the patient might think … it (treatment) might not work” (Haematologist: Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1024) and “I’m not going to force the truth [dying] down their throat” (Haematologist Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025). Moreover, the view was that “people can be cured … so it's quite difficult picking the right time to have those conversations” (Specialist palliative care Doctor; McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5).

These concerns were strongly based on HCPs views that patients associated palliative care with EOL (Cormican & Dowling, 2016; LeBlanc et al., 2015; McCaughan et al., 2018b; McGrath & Holewa, 2006; Mollica et al., 2018; Morikawa et al., 2016; Wright & Forbes, 2017), “the death team … to expedite people's death” (Palliative care doctor: Mollica et al., 2018, p. 618), and “somewhere you go to die” (McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5). Some HCPs also expressed their view that palliative care meant EOL (LeBlanc et al., 2015; Mollica et al., 2018; Wright & Forbes, 2017); “I have worked on a team where a Macmillan nurse [palliative care] wasn't allowed on the ward round, because the consultants felt that meant that the patients might think that some of them were dying (laughs)” (Doctor: Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 41).

Nurses and doctors needed “a deep awareness” (Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89) before considering transition to palliative care. Doctors looked for benchmarks to guide them in deciding when it was time to “start talking about EOL [end of life care] care” (Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398), such as “… when you know there's no drug, no treatment, nothing to propose” (Prod’homme et al., 2018, p. 1025) and “if QOL is declining because of drug toxicities, cytopenias, or multiple trips to the hospital” (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e398). While it was sometimes difficult for haematologists to know when to refer to hospital‐based palliative care (Morikawa et al., 2016), decisions for referral were made based on patients’ declining QoL (Odejide et al., 2014), taking time to think about the patient's prognosis by introducing the “Surprise” Question (Gerlach et al., 2019), and how many treatments have been given and their symptoms and declining performance status (LeBlanc et al., 2015; McGrath & Holewa, 2007a).

3.2.3. Hospice, home or hospital?

Explicit communication about the transition to palliative care “allowed an open dialogue with the patient” (Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 90). However, transition to the last palliative phase often happened at the terminal phase (Dalgaard et al., 2010). Interprofessional communication between nurses and doctors often “did not run smoothly” (Dalgaard et al., 2010, p. 89); “you call the doctors, and no one wants to take the responsibility of initiating the morphine pump … it is as if they do not understand you” (Nurse: Grech et al., 2018, p. 240). While doctors focused on treatment, nurses focused on patients’ QoL (Dalgaard et al., 2010) and doctors could be “… very dismissive … I was made to feel I want to put everyone into the LCP [Liverpool care pathway] … and I was belittled for that” (Haematology nurse: McCaughan et al., 2019, p. 73). A need for “relationship building” between palliative care and haematology specialists was highlighted, where “we're learning about their speciality as much as they're learning about us and it's just about shared understanding” (Specialist Palliative Care Doctor; McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 7).

However, there was a concern that the transfer to palliative care was failing patients: “sometimes when you are emotionally involved with the patient you feel you're um abandoning them or you feel … you've failed them” (Doctor “B”: Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 43), making them “feel like we've written them off” (Doctor “E”: Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 43) and “by transferring somebody purely to palliative care, you almost feel as if you're washing your hands of them” (Haematology nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81). “A hospital death may be an appropriate death … and it may be done very well actually” (Haematologist: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81). In addition, it was the view that “a lot of people choose to die in hospital … they [patients] just feel safe … this is their second home” (Haematology nurse, McCaughan et al., 2019, p. 73).

Some haematologists expressed concern that hospice care could not meet the needs of haematological patients because of their transfusion needs (McCaughan et al., 2018a; Odejide et al., 2014; Wright & Forbes, 2017); “Right now, the gap between home hospice and acute care hospitals is just too wide for our patients” (Doctor: Odejide et al., 2014, p. e399), and giving blood products was “not part of [hospice] end‐of‐life care” (Doctor: Wright & Forbes, 2017, p. 41). However, they also agreed that this issue could be overcome if “designated hospices … would provide maybe once a week platelet or red cell transfusion” (Odejide et al., 2014, p. e403). Strict criteria for specialist palliative care in the community were also mentioned as an obstacle for haematology patient referral, “she [patient] didn't meet the criteria” (Specialist Palliative care nurse: McCaughan et al., 2018b, p. 5). Moreover, some patients wanted to stay in hospital for “… the reassurance (of) still being watched” (McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 80).

A major concern for haematologists, nurses, GPs and palliative care doctors was the risk of acute bleeding at home (McCaughan et al., 2018a; McGrath & Leahy, 2009), “which is a very unpleasant death” (Nurse: McGrath & Leahy, 2009, p. 531) and “… you would have to have a robust family and carers to cope with that” (Palliative doctor: McCaughan et al., 2018a, p. 81). Doctors also expressed the concern that “a patient exsanguinating in front of his family is not very appropriate EOL care” (Odejide et al., 2014, p. e399).

4. DISCUSSION

This evidence synthesis is the first known study to synthesise all available qualitative research on HCPs’ views of experiences of palliative care for patients with haematological malignancies. The results show with high confidence (based on the GRADE CERQual) that doctors’ therapeutic optimism and hope of a cure results in many patients with a haematologic malignancy being actively treated until EOL. This finding reflects the challenge of maintaining hope of a cure in the shadow of an unpredictable treatment journey where patients can rapidly deteriorate. Findings elsewhere report the potential for cure for many blood cancers at an advanced stage, unlike most solid cancers which are incurable at an advanced stage (stage IV) (Odejide et al., 2016). Moreover, intensive medical care often continues for these patients even as they approach their final week of life (Brück et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2015; Soares et al., 2019). Doctors’ therapeutic optimism is driven by their commitment to giving hope to their patients, which is at the heart of the doctor–patient relationship (Bressan, Iacoponi, Candido De Assis, & Shergill, 2017) and is one of the core elements of the “art of medicine” (Mambu, 2017). Therapeutic optimism or hope can be defined as a positive emotional outlook on the future resulting in a wish for a particular healthcare outcome (Hallowell et al., 2016). The therapeutic optimism displayed by haematologists appears to be “situational optimism,” which is focused on a particular event or activity and hoping for the best (Jansen, 2011). While most haematologists value a palliative care philosophy (Odejide et al., 2017), they are more willing to refer patients early in their disease trajectory if the term “palliative care” is replaced with “supportive care” (Hui et al., 2015; Tricou et al., 2019). Supportive care alongside active curative treatment can achieve the best results for patients (El‐Jawahri et al., 2016; Potenza, Luppi, Efficace, Bruera, & Bandieri, 2020; Webb, LeBlanc, & El‐Jawahri, 2019). Moreover, some doctors may fear they will take away patients’ hope if they discuss palliative care (Mack & Smith, 2012). Some nurses’ fear of taking patients’ hope away was also evident in this synthesis as was nurses’ expression of distress when patients died while being actively treated. These contrasting views illustrate the complexity of practice and the need for careful consideration of each patient's evolving needs. Moreover, while maintaining patients’ hope is essential, a “false hope” for haematology patients and their families can result (Button et al., 2014, p. 375). Patient expectations also need consideration. Haematology patients have been described as “fighters” who “just want to keep living … and don't want to give up” (Cormican & Dowling, 2016, p. 55).

This synthesis also found (with high confidence) that HCPs considered the patient's age, and signs of deteriorating QoL, when deciding to continue with treatment or considering discussing the introduction of palliative care. Using the patient‐centred Myeloma Patient Outcome Scale can help HCPs assess and monitor symptoms in myeloma patients (Osborne et al., 2015; Ramsenthaler et al., 2017). However, recognising the dying process is difficult, particularly among patients with haematological malignancies because of the possibility of cure at a late stage as well as the possibility of sudden deterioration and death (Cheng et al., 2015; Leung et al., 2012; McCaughan et al., 2019). Button, Chan, Chambers, Butler, and Yates (2016) identified pain, haematopoietic dysfunction, dyspnoea and reduced oral intake being present in the final three months of life for people with a haematologic malignancy. Their work has been further developed to include 11 indicators, (a) advancing age, (b) declining performance status, (c) presence of co‐morbidities, (d) disease status, (e) persistent infections (bacterial and viral), (f) fungal infections, (g) severe graft‐versus‐host disease, (h) requiring high care (i.e., frequent hospitalisations, prolonged hospitalisations), (i) signs of frailty, (j) treatment limitations, and (k) anorexia and/or weight loss (Button, Gavin, et al., 2019). While clinical subjective and objective indicators provide a useful tool for clinicians in determining risk of deteriorating and dying in haematology patients (Button, Gavin, et al., 2019), the possibility of sudden death is a reality for many haematology patients. The unpredictable disease trajectory and haematologists’ lack of time and skills to embark on difficult conversations with patients limit the usefulness of the “Surprise” Question (an intuitive estimate of survival) in this setting (Gerlach et al., 2019). However, training in communication skills and availability of time could result in the “Surprise” Question exploring what is important to patients in terms of their QoL.

We also found, with high confidence, that HCPs were concerned about the risk of catastrophic bleeds and considered hospice care more suitable for patients with non‐haematological malignancies. When compared to patients with solid tumours requiring palliative care, those with haematological malignancies are more likely to exhibit severe neutropenia, leukopenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia (Ishida et al., 2019). Bleeding complications are common at EOL in patients with haematology malignancies (Brück et al., 2012), resulting in significant transfusion requirements for haematology patients at EOL in both hospital and hospice settings in the last week of life (Brück et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2015). Transfusion support is useful in improving symptoms of dyspnoea, fatigue and bleeding (Soares et al., 2019). However, haematologists have expressed concern that hospice care could not meet the needs of patients because of their transfusion needs (McCaughan et al., 2018a; Odejide et al., 2014; Wright & Forbes, 2017). Moreover, when patients need multiple blood and platelet transfusions requiring frequent visits to hospital, haematologists may be reluctant to hand over the care to palliative care (Ofran et al., 2019). While new models of hospice that accommodate transfusion and continuing input from the haematology team are needed (Odejide et al., 2017), there is also a need for clinical guidelines on antibiotic and transfusion use in order to standardise palliative care for patients with haematological malignancies (Cheng et al., 2015; LeBlanc, 2016).

It is known that patients with haematological malignancies are less likely to be offered access to hospice care when compared to patients with solid tumours (Howell et al., 2011; Hui et al., 2015), and when offered, their average length of stay in hospice care before EOL is reported to be 14.8 days (Cheng et al., 2015). Home care is also not an option for the vast majority of haematological patients. Indeed, in a retrospective analysis of 580 patients who received home care, only 2.6% (n = 15) had a haematologic malignancy (Kodama et al., 2009). This is not surprising because these patients are more likely to require intravenous antibiotics and transfusions when compared to patients with solid tumours (Ishida et al., 2019). Risk of accidental falls at home is also higher among patients with haematology malignancies when compared to the general population, and they face a greater risk of developing severe complications (Tendas et al., 2013). Following an analysis of home care for 15 haematological patients, Kodama et al. (2009) suggest that haematology patients requiring frequent transfusion or platelet transfusions due to high risk of bleeding should be excluded from home care, and only patients with indolent disease who can take oral fluids should be offered home care.

Recent attention to the needs of haematology patients stresses that “referral (to palliative care) should be based on needs rather than life expectancy” (Porta‐Sales & Noble, 2019, p. 481). Introducing specific person‐centred palliative care plans for haematology patients attending outpatients has been reported to improve symptoms and significantly decrease visits to the ED and inpatient admissions (Draliuk, Perez, Yosipovich, & Preis, 2016). In addition, early palliative care integrated with standard care is reported to reduce symptom intensity and improve QoL for multiple myeloma patients (Federico et al., 2013). Moreover, evidence from a recent trial on the introduction of early palliative care for patients hospitalised for haematopoietic stem cell transplant showed that patients who received the inpatient palliative care intervention had a smaller decrease in QoL when compared to those who received standard care (El‐Jawahri et al., 2016). Finally, a promising new model of care is reported by Ofran et al. (2019) where a haematology palliative care team works under the supervision of senior haematologists. The team consists of two senior haematologists, nurses from both day and inpatient units, three social workers, two psychologists and one pastoral care provider, and referrals for patient evaluations are made to the nurse coordinator who ensures that a social worker undertakes a screening interview with the patient within 48 hr. None of the palliative care team prescribe or make treatment decisions unless approved by the treating haematologist. Reporting on the model's success after four years in operation, Ofran et al. (2019) highlighted that in 2014 before its introduction, 26/42 (62%) of the patients who died in the department did do while being ventilated, and this figure dropped to 42.5% (20/47) in 2017, without any changes in department staff or treatment protocols.

4.1. Study limitations and directions for new research

This review only included papers in the English language and the studies reflected the views of HC professionals working in Westernised healthcare settings. The findings may not reflect views of HC professionals in non‐Westernised cultures where conversations about palliative care and end‐of‐life care are often not culturally accepted (Dam, 2016). Three papers were reports on one UK study (McCaughan et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2019). Four papers were reports on one Australian study undertaken over fifteen years ago (McGrath & Holewa, 2006, 2007a, 2007b; McGrath & Leahy, 2009); therefore, the views and experiences reflected may have limited clinical relevance in the rapidly changing field of haematology.

While there was a good representation of haematologists and nurses working in haematology settings, representation of palliative care doctors and nurses was limited (n = 41). The methodologies adopted across the studies were mostly descriptive qualitative with only one study adopting a phenomenological approach (Grech et al., 2018). A more in‐depth exploration of HCPs’ experiences would be achieved with a phenomenological design. In addition, the different terminologies used for palliative care across the included studies were a challenge when synthesising the extracted data. Finally, further research is needed on the use of clinical indicators to determine how useful they are in guiding HCPs’ decision‐making regarding palliative care needs of patients.

5. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

This evidence synthesis highlights a need for more integration of palliative care in haematology settings. The model of palliative care proposed by Bruera and Hui (2012) offers an approach for this. This model focuses on identifying people at risk of dying to improve their end‐of‐life care. Nurses spend large amounts of time at patients’ bedside and are ideally placed to assess the factors that indicate if a person is highly likely to deteriorate and die and requires palliative care interventions (Button et al., 2016; Hopprich, Reinholz, Gerlach, & Weber, 2018). While the 11 clinical indicators identified by Button, Gavin, et al., (2019) could be used by both haematologists and specialist nurses as a screening framework to initiate sensitive discussions with patients and their families in both inpatient and outpatient settings, referral to palliative care should ideally be based on needs rather than life expectancy (Porta‐Sales & Noble, 2019). Moreover, this synthesis highlights a need for more co‐operation and communication between HCPs. Haematologists are well aware that “building bridges” with palliative care colleagues can result in “a uniform team,” which better serves patients and their families and reduces the current gaps in end‐of‐life care for patients with haematological malignancies (LeBlanc, 2016, p. 266).

6. NEW CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE

6.1. What we already know

Patients with a haematologic malignancy are not receiving appropriate or timely referrals to palliative care, and for those who do receive appropriate palliative care, it tends to happen later than those with a non‐haematologic malignancy. HCPs are more comfortable referring older patients for palliative care and fear that patients will lose hope if referred to palliative care.

6.2. What we do not know

There is little evidence on HCPs’ experiences of using clinical subjective and objective indicators as a tool for determining risk of deteriorating and dying in haematology patients.

6.3. What our review contributes to existing literature

This is the first known QES of HCPs’ views and experiences of palliative care for patients with a haematologic malignancy. Most of the studies included in this review were published after 2010 suggesting the interest HC professionals have in this area and a concern that improvements in integration between palliative and haematology services are needed. This review is therefore timely as it offers guidance to HCPs on the factors that influence late referral of patients to palliative care and could be used as a framework for discussion within clinical teams.

7. CONCLUSIONS

This QES has highlighted that haematologists often delay introducing palliative care because of their therapeutic optimism, hope of a cure and fear of taking away a patient's hope. While clinical subjective and objective indicators are useful in the assessment of haematology patients’ risk of deteriorating and dying, referral to palliative care should ideally be based on needs rather than life expectancy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Irish Cancer Society for funding to undertake this study (Irish Cancer Society Summer Studentship 2019—Social and Allied Health Sciences).

Dowling M, P Fahy, C Houghton, Smalle M. A qualitative evidence synthesis of healthcare professionals' experiences and views of palliative care for patients with a haematological malignancy. Eur J Cancer Care. 2020;29:1–25. 10.1111/ecc.13316

REFERENCES

- Boland, A. , Cherry, M. G. , & Dickson, R. (2014). Doing a systematic review. A student’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A. , Noyes, J. , Flemming, K. , Gerhardus, A. , Wahlster, P. , van der Wilt, G. J. , … Rehfuess, E. (2018). Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 99, 41–52. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, R. A. , Iacoponi, E. , Candido De Assis, J. , & Shergill, S. S. (2017). Hope is a therapeutic tool. BMJ, 359, 1 10.1136/bmj.j546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brück, P. , Pierzchlewska, M. , Kaluzna‐Oleksy, M. , Lopez, M. E. R. , Rummel, M. , Hoelzer, D. , & Böhme, A. (2012). Dying of hematologic patients—Treatment characteristics in a German University Hospital. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(11), 2895–2902. 10.1007/s00520-012-1417-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruera, E. , & Hui, D. (2012). Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(11), 1261–1269. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button, E. , Bolton, M. , Chan, R. J. , Chambers, S. , Butler, J. , & Yates, P. (2019). A palliative care model and conceptual approach suited to clinical malignant haematology. Palliative Medicine, 33(5), 483–485. 10.1177/0269216318824489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]