Abstract

Objective

The study explores how newly diagnosed patients with acute leukaemia and their patient ambassadors experience the mentorship during the patient ambassador support programme.

Methods

Explorative semi‐structured individual interviews (n = 28) were carried out in patients with acute leukaemia (n = 15) and their patient ambassadors (n = 13). Interpretive description was the methodological framework used for the thematic analysis of the qualitative interview data.

Results

Identified themes were as follows: (a) exchanging life experiences (subthemes: individualised support and a meaningful return); (b) existential cohesion; (c) interreflection; and (d) terms and conditions (subtheme: break in journey). Patients experienced a feeling of being understood, the cohesion leading to hope and a feeling of being able to cope with their situation. Patient ambassadors experienced a sense of meaningfulness and gratitude for life.

Conclusions

Patients and patient ambassadors experienced benefits from the individualised support. Their shared experiences created a connection and mutual mirroring, which led to a sense of hope and gratitude for life. Initiatives that introduce peer‐to‐peer support in newly diagnosed patients with acute leukaemia as part of treatment and in daily clinical practice are crucial. Future studies should further examine the feasibility of peer‐to‐peer support interventions along the trajectory of acute leukaemia.

Keywords: acute leukaemia, mentorship, patient ambassador, peer support, qualitative interviews, social support

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute leukaemia (AL), a malignant disorder of haematopoietic stem cells, is associated with morbidity and mortality (Short, Rytting, & Cortes, 2018). AL is classified into subtypes of acute myeloid or lymphoid leukaemia (AML/ALL) (Hoffman, Silberstein, Heslop, Weitz, & Anastasi, 2018). AML is the most common AL in adults with an incidence in Europe of 5.06 patients per 100.000 people (Roman et al., 2016). ALL has a bimodal distribution with a peak in childhood and then again in midlife with an incidence in Europe of 1.28 patients per 100.000 people.(Hoelzer et al., 2016). The trajectory has an acute onset followed by a significant disease and treatment‐related symptom burden, with a risk of developing psychological distress impacting quality of life (Ferrara & Schiffer, 2013; Leak Bryant, Lee Walton, Shaw‐Kokot, Mayer, & Reeve, 2015; Short et al., 2018; Zimmermann et al., 2013). The psychological morbidity following AL can influence recovery and adaptation of the illness in everyday life (Manitta, Zordan, Cole‐Sinclair, Nandurkar, & Philip, 2011).

Social support is defined as a multidimensional construct that refers to the psychological and material resources available to individuals through their interpersonal relationships (Cohen & Wills, 1985). The most influential theoretical perspective on social support and health outcomes indicates that social support protects people from the influence of stressful events (Cohen & Herbert, 1996; Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Social support increases adherence to treatment and improves health behaviour (Pinquart, Hoffken, Silbereisen, & Wedding, 2007; Shinn, Caplan, Robinson, French, & Caldwell, 1977). In patients with cancer, increased level of social support is associated with fewer psychological symptoms, improved well‐being and quality of life (Kornblith et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2019; Papadopoulou, Johnston, & Themessl‐Huber, 2013).

One‐to‐one peer support is social support that involves a cancer survivor providing emotional and experience‐based support to a patient in an earlier stage of treatment or recovery than the provider of peer support (Pistrang, Jay, Gessler, & Barker, 2012, 2013; Ussher, Kirsten, Butow, & Sandoval, 2006). Peers have the unique opportunity of providing experienced‐based informational, emotional and practical support beyond the scope of health professionals and their own social network (Dennis, 2003). People giving help profit through self‐development by solving their own problems in the process of helping others (Riessman, 1965). A 2015 systematic review (Meyer, Coroiu, & Korner, 2015) found that peer‐to‐peer support led to benefits in psychological adjustment, self‐efficacy and high satisfaction with and acceptance of the support in patients with cancer. Yet, the included studies were exclusively quantitative. Additionally, few studies have focused on the peers’ experiences of mentorship in one‐to‐one interventions, especially in relation to the perspective of the provider of peer support (Pistrang, Jay, Gessler, & Barker, 2013).

The existing evidence on peer‐to‐peer support within cancer is based on other malignancies than haematology, primarily breast and prostate cancer (Hoey, Ieropoli, White, & Jefford, 2008; Meyer et al., 2015). Because of the disease and treatment‐related symptom burden posed by AL, the existing research can, only to a limited extent, be transferred to patients with AL, creating a lack of research and evidence in peer‐to‐peer support interventions for the AL patient group. In the current study exploring the experiences of a peer support intervention, a peer support provider is named a patient ambassador.

The purpose of this study was to explore how newly diagnosed patients with AL and their patient ambassadors experience the mentorship during patient ambassador support as a means to gain new knowledge and insight into this unique support.

2. METHODS

Interpretive description (ID) is applied as a methodological framework in this explorative qualitative study with the objective of informing and improving clinical practice (Thorne, 2016). ID combines aspects from traditional qualitative methods and with its inductive approach focuses on applied science within health science discipline (Thorne, Kirkham, & O'Flynn‐Magee, 2004).

2.1. Setting

This study is part of a feasibility intervention trial investigating patient ambassador support in newly diagnosed patients with AL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03493906). The trial comprises a 12‐week support intervention for newly diagnosed patients with AL provided by patient ambassadors. Patients are included within the first two weeks from time of diagnosis. A patient ambassador in this study is defined as having previously been diagnosed with and treated for AL and is in complete remission. Patient ambassadors have attended an obligatory one‐day preparatory educational course and had the opportunity to attend regular network meetings with supervision from a psychologist. Patients and ambassadors were encouraged to engage in four personal meetings during the intervention; however it was not a requirement.

2.2. Participants and procedures

The sample is based on a purposive strategy to achieve maximal variation and information‐rich interviews, which is why sampling continued until diversity was reached (Thorne, 2016). Participants were approached by the primary investigator, KHN, within two weeks after completing patient ambassador support in the period of June 2018 to January 2019. Inclusion criteria were patients and patient ambassadors who had participated in and completed the intervention within the last two weeks and who were able to understand, speak and read Danish. The exclusion criteria were cognitive disorders and unstable medical conditions. The sample consisted of 28 participants comprising 15 patients and 13 patient ambassadors, with one patient ambassador interviewed twice while having two separate mentorships.

2.3. Data collection

Separate semi‐structured interview guides were developed for patients and for patient ambassadors, based on an evaluation of the existing literature, to identify the theoretical and analytic categories for the topics of research (Tables 1 and 2). The participants had the choice of being interviewed at home (n = 4), at the research facility (n = 8) or at the hospital in connection with a scheduled outpatient visit (n = 16). All interviews were conducted by KHN, lasted 30–90 min, were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

TABLE 1.

Patient interview guide

| Topic | Research questions | Interview questions |

|---|---|---|

| Expectations prior to patient ambassador support | What thoughts and expectations do the patient have in relation to receiving patient ambassador support? |

What thoughts and considerations did you have before getting in contact with your patient ambassador? What expectations did you have prior to having contact with your ambassador? Were these expectations met? Did you experience any discrepancies between your expectations and what you experienced? |

| Experiencing patient ambassador support | How does the patient experience the patient ambassador support? |

How did your contact with your patient ambassador begin? How did you experience the progression of the actual contact? Who took the initiative? What type of contact did you have? What type of contact did you have the most? Which type of contact do you prefer? What type of experience worked the best or worst for you? How often did you have contact with your patient ambassador? How was the match between you and your patient ambassador? How did you experience your relationship with your patient ambassador? What did you talk about during your conversations? What personal experiences from the patient ambassador did you ask about? What specifically worked well? Which conversations were particularly significant? What was difficult/challenging about having a patient ambassador? What did you do when it became difficult or challenging? What conversations were particularly difficult? What do you think about how the program ended? |

| The significance of the support | What significance does the support have for the patient? |

What significance has it had for you to have a patient ambassador during your course of treatment (physically, psychologically, socially, symptoms)? Did you seek support from anyone else besides your ambassador? If yes, who (e.g. a psychologist or priest)? |

| The optimal patient ambassador support programme | What is the optimal patient ambassador support program? |

Did you lack any information or knowledge from your patient ambassador or the primary investigator? To what extent was your patient ambassador sufficiently prepared for his or her role as ambassador? From your experience, what would you consider to be the optimal patient ambassador support program? (context, matching, amount of contact, content) |

TABLE 2.

Patient ambassador interview guide

| Topic | Research questions | Interview questions |

|---|---|---|

| The role as ambassador | How does the ambassador experience his or her role in the supportive and mentoring relationship with the patient? |

What motivated you to volunteer as a patient ambassador? Did your motivation change during or after the program ended? What thoughts and considerations did you have regarding the patient ambassador role? What expectations did you have to your role as patient ambassador? Were these expectations met? Did you experience any discrepancies between your expectations and what you experienced? |

| Patient ambassador support | How does the ambassador experience the patient ambassador support? |

How did your contact with the patient begin? How did you experience the progression of the actual contact? What type of contact did you have? What type of contact did you have the most? What type of contact did you experience worked the best or worst? What was your preference? How often did you have contact with your patient? How was the match between you and your patient? How did you experience your relationship with the patient? What did you talk about during your conversations? What personal experiences did you share? What specifically worked well? Which conversations were particularly of value to the patient (from your perspective)? What was difficult during the program? What did you do when it was difficult? Which conversations were particularly difficult? Did you experience the need to contact to the patient's relatives? What did you think about how the 12‐week program ended? |

| The value of the role as ambassador | What value does the support have for the patient ambassador? | What value did it have for you to be patient ambassador? |

| The need for support as patient ambassador | To what extent is there a need for support as a patient ambassador? |

Did you experience a need for support as a patient ambassador? If yes, what type of support did you need and from whom? Did you participate in the patient ambassador support network meetings? If yes, what impact did these meetings have on you as a patient ambassador? What was especially helpful from these meetings? If no, why did you not participate in the meetings? Did you receive support elsewhere? |

| The optimal patient ambassador support programme | What is the optimal patient ambassador support program? |

How was the patient ambassador training program useful compared to what you experienced? Was there any information, knowledge or support lacking during the program? If yes, explain. How do you think the patient ambassador support program can be improved? |

2.4. Data analysis

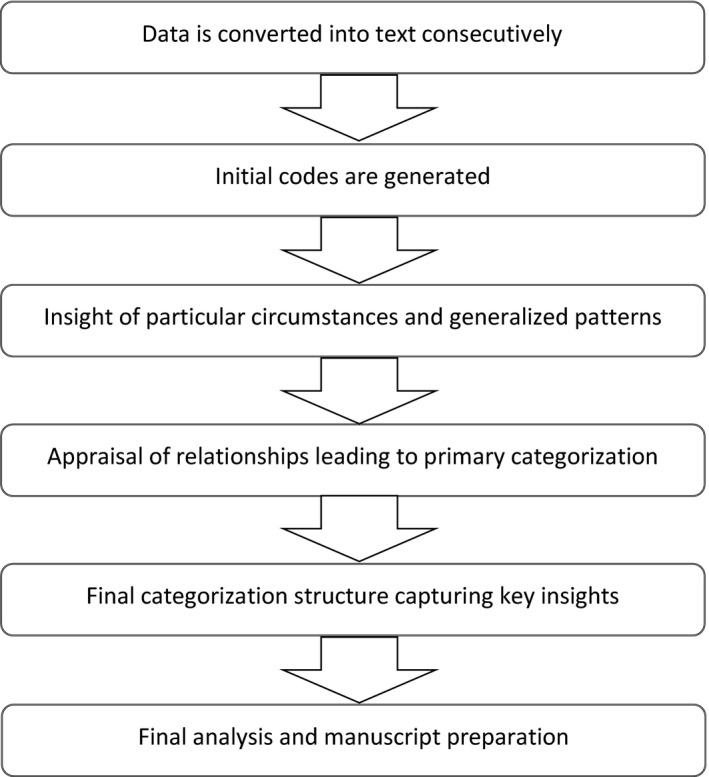

Consistent with ID methodology, data analysis was conducted continuously as interviews were transcribed as the study progressed (Thorne, 2016). Notes on analytical insights were generated from concurrent reflections during data collection and used in the process of analysis (levels one and two). Data were organised and managed by NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version2015, 2015). Thematic analysis was carried out by three researchers: KHN, DO and MJ.(Braun & Clarke, 2006) The analysis comprised six levels (Figure 1) (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, 2017). KHN carried out the six levels, while DO and MJ contributed with triangulation and consensus on coding and the themes at levels four to six.

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of the analysis process. A model on thematic data analysis framed by the interpretive description methodology (Thorne, 2016)

3. FINDINGS

Thirty‐seven participants were screened, and seven patients were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are as follows: too ill (n = 1), palliative care (n = 1), death (n = 3), no established contact (n = 1) and relapse (n = 1). Of the eligible participants approached, one patient and one patient ambassador declined participation due to lack of motivation. The number of participants included was 28, comprising patients (n = 15) and patient ambassadors (n = 13). Tables 3 and 4 present the characteristics of the patients and patient ambassadors. Women made up 67% in patients and 69% in patient ambassadors; age range was 27–73 (mean age, patients: 49 years, patient ambassadors: 51 years); AML was the most frequent diagnosis in patients (73%) compared to patient ambassadors (54%).

TABLE 3.

Patient characteristics

| ID | Gender | Age in years | Diagnosis | Marital status | Level of education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

49 (mean) 27–73 (range) |

5.6 (mean) 3–7 (range) |

||||

| P1 | Male | 27 | ALL | In a relationship | Level 7 |

| P2 | Female | 28 | ALL | In a relationship | Level 7 |

| P3 | Male | 31 | ALL | Married | Level 6 |

| P4 | Male | 32 | AML | In a relationship | Level 5 |

| P5 | Male | 33 | ALL | Married | Level 6 |

| P6 | Female | 33 | AML | Single | Level 6 |

| P7 | Female | 40 | AML | Single | Level 6 |

| P8 | Female | 50 | AML | Married | Level 3 |

| P9 | Male | 51 | AML | Married | Level 7 |

| P10 | Female | 59 | AML | Single | Level 5 |

| P11 | Female | 68 | AML | Married | Level 7 |

| P12 | Female | 70 | AML | Married | Level 5 |

| P13 | Female | 70 | AML | Married | Level 6 |

| P14 | Female | 72 | AML | Married | Level 5 |

| P15 | Female | 73 | AML | Married | Level 5 |

Level of education, is based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ISCED 2011 has nine education levels, from level 0 to level 8.

Abbreviations: ALL, Acute Lymphatic Leukaemia; AML, Acute Myeloid Leukaemia; ID, Personal identification number; Level 0, Early childhood education; Level 1, Primary education; Level 2, Lower secondary education; Level 3, upper secondary education; Level 4, Post‐secondary non‐tertiary education; Level 5, short‐cycle tertiary education; Level 6, Bachelors or equivalent level; Level 7, Masters or equivalent level; Level 8, Doctoral or equivalent level.

TABLE 4.

Patient ambassador characteristics

| ID | Gender | Age in years | Diagnosis | Month since diagnosis | Bone marrow transplant | Marital status | Level of education | Number of patients supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

51 (mean) 26–75 (range) |

40 (mean) 18–90 (range) |

5.6 (mean) 4–7 (range) |

||||||

| A1 | Male | 26 | ALL | 71 | Yes | Single | Level 7 | 1 |

| A2 | Female | 29 | AML | 27 | Yes | In a Relationship | Level 6 | 1 |

| A3 | Male | 39 | ALL | 24 | Yes | Married | Level 4 | 2 |

| A4 | Male | 41 | ALL | 60 | No | Married | Level 5 | 2 |

| A5 | Female | 46 | AML | 44 | No | Married | Level 5 | 1 |

| A6 | Female | 46 | AML | 27 | Yes | Married | Level 5 | 3 |

| A7 | Female | 49 | ALL | 19 | Yes | Single | Level 7 | 2 |

| A8 | Female | 49 | AML | 74 | Yes | Married | Level 4 | 1 |

| A9 | Female | 53 | AML | 27 | Yes | Married | Level 5 | 2 |

| A10 | Female | 66 | ALL | 90 | Yes | Married | Level 6 | 2 |

| A11 | Male | 70 | ALL | 26 | Yes | Married | Level 5 | 1 |

| A12 | Female | 75 | AML | 20 | No | Widowed | Level 7 | 1 |

| A13 | Female | 75 | AML | 18 | Yes | Widowed | Level 7 | 1 |

Level of education, is based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ISCED 2011 has nine education levels, from level 0 to level 8.

Abbreviations: ALL, Acute Lymphatic Leukaemia; AML, Acute Myeloid Leukaemia; ID, Personal identification number; Level 0, Early childhood education; Level 1, Primary education; Level 2, Lower secondary education; Level 3, upper secondary education; Level 4, Post‐secondary non‐tertiary education; Level 5, short‐cycle tertiary education; Level 6, Bachelors or equivalent level; Level 7, Masters or equivalent level; Level 8, Doctoral or equivalent level.

The analysis identified four overarching themes: (a) exchanging life experiences (subthemes: individualised support and a meaningful return); (b) existential cohesion; (c) interreflection; and (d) terms and conditions (subtheme: break in journey).

3.1. Exchanging life experiences

The impact of AL and its treatment on the patient's well‐being determined the type of knowledge and experiences they requested from the patient ambassadors. Some requested information and advice on their treatment, symptoms or side effects, and others expressed a need for support in managing social issues in both family and working life, as well as in handling the practical challenges in everyday life.

I asked her about her social life, because you become isolated when the treatment lasts so long. I stopped working, and that's why I need a social network. She gave me some ideas and inspiration for doing something different. (P11)

Patients expressed a need for support during three phases of treatment: initial treatment, stem cell transplantation and survivorship. The patient ambassadors exchanged experiences with the patients that they had had a need for during their own treatment.

3.1.1. Individualised support

The patient ambassadors coordinated and initiated the support. The content and type of support was individualised depending on the degree of symptom burden, treatment side effects, social conditions and personal preferences. The type of contact (text message, telephone or face to face) was chosen by the patient which was by text message in the beginning. This type of contact was experienced as less committing, created emotional distance and showed consideration for the patients vulnerable and burdened situation.

One, you don´t feel up to par; two, you're tired; three, you feel sick; and four, you don't look that great. Then you just don't feel like having people stop by. Then a text message is great, because it's non‐committal and neutral. But it still gives you the feeling that there's someone thinking of you. (P7)

Conversely, some patient ambassadors experienced the use of text messages required increased reflection. Contact varied from a single long telephone conversation to weekly contact. Satisfaction with the support was independent of the frequency of contact; the patients described the intervention had significant impact on how they had managed their situation. A young man described how the support had an impact on his everyday life:

He also had two small children at the time and was torn away from his family life and unable to be present. Asking him how they managed everyday life and solved these challenges was very useful. You need to gain control of practical tasks before you can adapt to what's happening to you. (P3)

3.1.2. A meaningful return

The patient ambassadors were motivated by having experienced the same support during their own trajectory, and others had experienced an unmet need for this support. They were motivated by the desire that their experiences might help and have a positive impact on certain aspects of life for others in their current situation.

I actually think it's been a nice thing to think about. All the bad experiences, they can be turned into something positive. (A6)

Sharing life experiences was meaningful, because doing so might help make the illness pathway easier.

There's an important message in helping each other. This has been my greatest motivation. It means a lot; it's difficult to put into words. It's not only helping others, but it also helps you to give. (A8)

For these reasons, following and supporting others in their pathway had a therapeutic effect on the patient ambassadors.

3.2. Existential cohesion

Existential cohesion arose in the relationship between patients and patient ambassadors in consequence of their shared experiences with the disease and treatment. This cohesion allowed a unique sharing and mutual reflection on life experiences which evolved into a relationship. The patient ambassador's advice was respected, because it was based on personal experience.

My own friends' responses do not have the same effect on me as his do. He knows exactly what it's like. (P11)

This aspect also presented new opportunities to talk about life and the future with someone who understood their thoughts and feelings.

They expressed a willingness to continue their relationship because of a shared desire to stay abreast of one another's lives and because the patients were interested in continuing the relationship throughout the treatment trajectory.

But how does my story end? It seems a bit strange to stop abruptly. We've talked a lot recently, and then suddenly it would end. It's nice to be followed all the way through. (P8)

Conversely, some patient ambassador's preferred not to have this kind of relationship with their mentee, because they were afraid the disease would worsen someday, creating too much of an emotional burden to continue the relationship.

3.3. Interreflection

Their shared experiences with the disease and treatment enabled mutual reflection. Uncertainty about the future increased the patients' need to mirror themselves in their patient ambassador which resulted in feelings of hope. Meeting someone who has completed treatment and returned to everyday life gave patients strength and hope for the future.

It was nice to meet someone who had come out on the other side. That's just what I needed him for. He was my beacon. (P1)

The patient ambassadors also reflected themselves in the patients, helping to put their own lives into perspective realising how far they had come in their disease trajectory, creating gratitude for life.

It was important for the patient and patient ambassador to be matched according to type of AL, gender and family relationships. Being in the same phase of life was a crucial factor in terms of recognisability and the interreflection of life. A good match between the patient and the patient ambassador was essential in establishing the relationship. A well‐aligned match increased the likelihood that the patient ambassadors experienced thoughts and emotions related to their own course of treatment, though not of an emotionally burdensome nature.

3.4. Terms and conditions

Patients and patient ambassadors entered into the mentorship on unequal terms and conditions. This induced challenges with establishing the relationship due to the patient's vulnerable situation, with some indicating that this challenged their ability to share experiences and feelings with a stranger. The impact of their symptom burden reduced the amount of energy they had to establish and maintain contact, affecting the ability to have face‐to‐face meetings.

When I was well and at home, there were many practical and social things to do. When I was feeling sick, I didn’t have the strength. We had contact during those in‐between periods. (P9)

Regardless, patients experienced the onset of illness as appropriate in relation to their current need for support.

They experienced different levels of expectations prior to establishing their relationship. The patient's vulnerable situation made it difficult for them to recognise their needs, causing them to accept all the help they could get, with very few expectations which were often fulfilled. Ambassadors, on the other hand, had more time to prepare and raise their expectations. One patient ambassador stated:

I just think I had expected and imagined myself being an oracle, someone who could generously share my experiences and help that person having a less difficult course of treatment. (A3)

Some ambassadors said that they did not have a clear sense of whether their role had been significant to the patient. Therefore, receiving patient feedback was crucial regarding having their expectations met.

The patients and patient ambassadors were in different illness and survivorship phases, increasing the risk of an inappropriate exchange of knowledge. “When somebody asks about your disease, it's like pressing a button. I almost blew her over, and now realize I should have shut up.” (A10)

Supervision helped them to deal with any potential challenges and meeting other ambassadors also imparted a feeling of solidarity, helping them not feel alone as a long‐term survivor of AL.

3.4.1. Break in journey

One premise that both groups were aware of was the patient's risk of treatment resistance and the ambassador's risk of relapse. A few mentorships ended prematurely, because the patients were either transferred to palliative care or died. Despite this experience, the patient ambassador wished to mentor a new patient because they felt they still had experiences to share.

Of course, you get emotionally involved, but it doesn't go that deep. What hit me the most was when her husband wrote me that evening to tell me she was gone. (A6)

Another patient ambassador experienced a relapse during the intervention, causing the patient concern because of the ambassador's function as a role model. The worry did not persist, however, and the new circumstances meant that they took a more equal role.

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings provide important insight into patient ambassador support in newly diagnosed patients with AL and their patient ambassadors, shedding light on the benefits and challenges of this support. We found that both patients and patient ambassadors experienced substantial benefit from the support. Patient ambassadors experienced the mentorship as meaningful, and due to their mutual existential cohesion, both groups were able to mirror each other's experiences, creating hope and gratitude for life. An important issue to point out in terms of initiating patient ambassador support is that the patient ambassador relationship is based on unequal. We found that individualised support was essential as a result of the symptom burden and personal preferences.

Research has identified several mechanisms linking social support to health outcomes (Ditzen & Heinrichs, 2014; Pinquart et al., 2007). The stress‐buffering model predicts the level of social support needed to buffer the effects of stressful events in a person's life. In this model, social support is beneficial, because it decreases the negative effects of stress on health outcomes (Cohen & Herbert, 1996; Cohen & Wills, 1985). Our previous research indicates that newly diagnosed patients with AL consider social support, especially from other patients with AL, as a lifeline, helping them to actively manage their new life situation and to regain hope (Norskov, Overgaard, Lomborg, Kjeldsen, & Jarden, 2019). The present study identified various benefits derived from patient ambassador support that may explain the mechanisms linking social support with improved health outcomes in both peer recipients and peer supporters.

Patients experience feelings of uncertainty and a threat to their existence when diagnosed with cancer. A literature review (2007) identified hope as an important factor in the lives of newly diagnosed patients with cancer (Chi, 2007). Hope can help patients deal with uncertainty of their cancer diagnosis (Butt, 2011). Our study consistently indicated that shared experiences result in mutual mirroring, leading to a feeling of hope and belief in their ability to cope with their situation. These findings are comparable with a qualitative study (2012) exploring experiences in peer support recipients that found decreased isolation and increased hope in patients receiving support from peers with a similar cancer diagnosis (Pistrang, Jay, Gessler, & Barker, 2012). Similar results were found in a recent cross‐sectional study (2015) exploring the determinants of hope in patients with cancer, showing that patients who shared their experiences with others were more hopeful (Proserpio et al., 2015). Hope can enhance the capacity of patients with AL to adapt to the life‐threatening disease (Chi, 2007). Our results emphasise that social support enhances hope which, in patients with AL, is crucial because of the often long and fluctuating treatment trajectory.

In accordance with previous research, our results showed that supporting others was meaningful and gave a new perspective on their own lives which led to self‐development (Pistrang et al., 2013; Riessman, 1965; Skirbekk, Korsvold, & Finset, 2018). This is consistent with the results of a qualitative study (2012) exploring the experience of peer supporters, where supporters gained closure (Pistrang et al., 2013). The patient ambassador role becomes a part of their own long‐term psychological recovery and also represents self‐support for the supporter. This is an important aspect since many of the patient ambassadors were long‐term survivors with limited contact to the health care system and survivorship support. Thus, implementing patient ambassador support has a significant impact on recovery and survivorship in long‐term survivors of AL (Margolis et al., 2019).

We identified the match between the patient and patient ambassador to be of pivotal importance for the success of the mentorship. Being in the same phase in life was a critical factor in terms of mirroring life experiences. Similar results have been identified in earlier peer‐to‐peer studies in patients with cancer (Pistrang et al., 2013; Skirbekk et al., 2018). According to social comparison theory, peer support can validate the patient's own feelings, concerns and experiences by using comparisons to cope, to reduce the threat and to find ways to meet challenges (Suls & Miller, 1977). Conversely, we found that a good match increased the patient ambassadors’ reflections on their own trajectory, with past emotions returning, causing some patient ambassadors needing support. However, support from regular network meetings was sufficient to manage these emotions. For this reason, when initiating patient ambassador support, it is essential to have a comprehensive diverse patient ambassador corps to successfully match participants. But, more importantly, it is pivotal to prioritise and arrange regular network meetings, so patient ambassadors have the opportunity to receive supervision.

The AL disease and treatment trajectory is characterised by causing a significant symptom burden challenging the patient's physical, psychological and social well‐being with supportive care needs that vary during the trajectory of treatment (Hall, Sanson‐Fisher, Lynagh, Tzelepis, & D'Este, 2015; Tomaszewski et al., 2016; Zimmermann et al., 2013). Our results suggest that peer‐to‐peer support should be adjusted individually due to variations in symptom burden, supportive care needs and personal preferences regarding type of contact. Importantly, we found that patients with a high symptom burden had difficulty maintaining contact with their patient ambassador even though they needed the support. However, despite limited contact, they experienced that the support had a positive impact on how they managed their situation. This emphasises that individualised support is important as patients' needs and preferences vary along the disease trajectory.

We identified some challenges as a result of the patients and patient ambassadors being on unequal terms and conditions. Despite the risk of becoming critically ill or dying, they agreed that the support was unique and that the unequal conditions should not be considered a barrier for others. This is consistent with a qualitative study (2012) in women with gynaecological cancer, where peer supporters receiving the news of their patient's death would do it again (Pistrang et al., 2013). An updated systematic review (2015) on one‐to‐one peer support in cancer care found similar results and reported that peers who experienced challenges in their role did not feel overwhelmed by their duties, if they had access to supervision (Meyer et al., 2015). It is crucial to include this aspect in the patient ambassador's preparation and education when implementing this type of support in clinical practice.

4.1. Methodological discussion

We used information power to guide and evaluate the study's adequate sample size (Malterud, Siersma, & Guassora, 2015). Consistent with the ID approach, our sample was purposive, which enhanced maximal variation and the selection of information‐rich cases (Thorne et al., 2004). Limitations include that the sample had more women than men as a consequence of the characteristic of eligible participants diagnosed with AL in the feasibility trial in this specific time period from which the participants in the present study were enrolled. The unequal distribution of gender among patient ambassadors was due to the patient's preference for same gender in matching. Our findings do not provide insight into specific demographic characteristics, for example, young adults, sex, level of social network. We recommend that future research focus on these specific characteristics to gain further knowledge about this support and to enhance its applicability in clinical practice. These findings are limited to the experience of peer‐to‐peer support in patients and their ambassadors during the initial period of diagnosis and treatment. Consequently, future studies should explore the experiences of support further along the disease trajectory.

4.2. Conclusion

The findings provide new knowledge on how the mentorship between newly diagnosed patients with AL and their patient ambassadors is experienced during patient ambassador support. The experience‐based knowledge that was exchanged was influenced by how affected the patient was by their symptom burden, life situation and treatment, which meant the support was highly individualised. Shared experiences resulted in a sense of cohesion and mutual mirroring that created feelings of hope and gratitude for life. Supervision of patient ambassadors through network meetings was of crucial importance for managing potential challenges. One‐on‐one peer‐to‐peer support in newly diagnosed patients with AL as part of treatment and in daily clinical practice is important and deserves greater attention. Future studies should examine the feasibility of peer‐to‐peer support interventions during the survivorship trajectory of AL and in patients with other haematological malignancies.

4.3. Practice implications

Our findings provide useful insights for future initiatives involving peer‐to‐peer support and are potentially transferable and valuable to a broader context of patients with cancer or other life‐threatening diseases when implementing peer‐to‐peer support in clinical practice. These results stress the importance of social support from peers with first‐hand experience of the disease and treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study is registered with the Danish Protection Agency (no. VD‐2017–176). Each informant received written and verbal information on the study and assurance of confidentiality according to the principles for research stated in the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained before interviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the participation of patients and acknowledge the volunteer participation of the patient ambassadors involved in this study. Their passion for helping other patients by sharing their experiences was inspiring. This study is part of the Models of Cancer Care Research Program at Copenhagen University Hospital.

Nørskov KH, Overgaard D, Lomborg K, Kjeldsen L, Jarden M. Patient ambassador support: Experiences of the mentorship between newly diagnosed patients with acute leukaemia and their patient ambassadors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2020;29:e13289 10.1111/ecc.13289

Funding information

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butt, C. M. (2011). Hope in adults with cancer: State of the science. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(5), E341–E350. 10.1188/11.onf.e341-e350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, G. C. (2007). The role of hope in patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(2), 415–424. 10.1188/07.onf.415-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , & Herbert, T. B. (1996). Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 113–142. 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. (2003). Peer support within a health care context: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 40(3), 321–332. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen, B. , & Heinrichs, M. (2014). Psychobiology of social support: The social dimension of stress buffering. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 32(1), 149–162. 10.3233/rnn-139008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, F. , & Schiffer, C. A. (2013). Acute myeloid leukaemia in adults. Lancet, 381(9865), 484–495. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61727-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. E. , Sanson‐Fisher, R. W. , Lynagh, M. C. , Tzelepis, F. , & D'Este, C. (2015). What do haematological cancer survivors want help with? A cross‐sectional investigation of unmet supportive care needs. BMC Research Notes, 8, 221 10.1186/s13104-015-1188-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzer, D. , Bassan, R. , Dombret, H. , Fielding, A. , Ribera, J. M. , & Buske, C. (2016). Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Annals of Oncology, 27(suppl 5), v69–v82. 10.1093/annonc/mdw025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey, L. M. , Ieropoli, S. C. , White, V. M. , & Jefford, M. (2008). Systematic review of peer‐support programs for people with cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 70(3), 315–337. 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R. B. , Silberstein, E. J. , Heslop, L. E. , Weitz, J. I. , & Anastasi, J. (2018). Hematology – Basic principles and practice (7th ed.). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith, A. B. , Herndon, J. E. 2nd , Zuckerman, E. , Viscoli, C. M. , Horwitz, R. I. , Cooper, M. R. , … Holland, J. (2001). Social support as a buffer to the psychological impact of stressful life events in women with breast cancer. Cancer, 91(2), 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leak Bryant, A. , Lee Walton, A. , Shaw‐Kokot, J. , Mayer, D. K. , & Reeve, B. B. (2015). Patient‐reported symptoms and quality of life in adults with acute leukemia: A systematic review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), E91–E101. 10.1188/15.onf.e91-e101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y. , Wang, H. , Niu, M. , Zhu, X. , Cai, J. , & Wang, X. (2019). Longitudinal analysis of the relationships between social support and health‐related quality of life in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Cancer Nursing, 42(3), 251–257. 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. , Siersma, V. D. , & Guassora, A. D. (2015). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitta, V. , Zordan, R. , Cole‐Sinclair, M. , Nandurkar, H. , & Philip, J. (2011). The symptom burden of patients with hematological malignancy: A cross‐sectional observational study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 42(3), 432–442. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, M. , Austin, J. , Wu, L. , Valdimarsdottir, H. , Stanton, A. L. , Rowley, S. D. , … Rini, C. (2019). Effects of social support source and effectiveness on stress buffering after stem cell transplant. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26(4), 391–400. 10.1007/s12529-019-09787-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A. , Coroiu, A. , & Korner, A. (2015). One‐to‐one peer support in cancer care: A review of scholarship published between 2007 and 2014. European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl), 24(3), 299–312. 10.1111/ecc.12273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norskov, K. H. , Overgaard, D. , Lomborg, K. , Kjeldsen, L. , & Jarden, M. (2019). Patients' experiences and social support needs following the diagnosis and initial treatment of acute leukemia – A qualitative study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 41, 49–55. 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L. S. , Norris, J. M. , White, D. E. , & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, C. , Johnston, B. , & Themessl‐Huber, M. (2013). The experience of acute leukaemia in adult patients: A qualitative thematic synthesis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17(5), 640–648. 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M. , Hoffken, K. , Silbereisen, R. K. , & Wedding, U. (2007). Social support and survival in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Supportive Care in Cancer, 15(1), 81–87. 10.1007/s00520-006-0114-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrang, N. , Jay, Z. , Gessler, S. , & Barker, C. (2012). Telephone peer support for women with gynaecological cancer: Recipients' perspectives. Psychooncology, 21(10), 1082–1090. 10.1002/pon.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrang, N. , Jay, Z. , Gessler, S. , & Barker, C. (2013). Telephone peer support for women with gynaecological cancer: Benefits and challenges for supporters. Psychooncology, 22(4), 886–894. 10.1002/pon.3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proserpio, T. , Ferrari, A. , Vullo, S. L. , Massimino, M. , Clerici, C. A. , Veneroni, L. , … Mariani, L. (2015). Hope in cancer patients: The relational domain as a crucial factor. Tumori Journal, 101(4), 447–454. 10.5301/tj.5000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd., Version 10 (2015). NVivo. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo‐qualitative‐data‐analysis‐software/home [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, F. (1965). The "helper" therapy principle. Social Work, 10(2), 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, E. , Smith, A. , Appleton, S. , Crouch, S. , Kelly, R. , Kinsey, S. , … Patmore, R. (2016). Myeloid malignancies in the real‐world: Occurrence, progression and survival in the UK's population‐based Haematological Malignancy Research Network 2004–15. Cancer Epidemiology, 42, 186–198. 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, M. , Caplan, R. D. , Robinson, E. A. , French, J. R. Jr , & Caldwell, J. R. (1977). Advances in adherence: Social support and patient education. Urban Health, 6(4), 20–21, 57–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short, N. J. , Rytting, M. E. , & Cortes, J. E. (2018). Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet, 392(10147), 593–606. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31041-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirbekk, H. , Korsvold, L. , & Finset, A. (2018). To support and to be supported. A qualitative study of peer support centres in cancer care in Norway. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(4), 711–716. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls, J. , & Miller, R. (1977). Social comparison theory and research: An overview from 1954. In Social Comparison Processes (pp. 1–17). London: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S. , Kirkham, S. R. , & O'Flynn‐Magee, K. (2004). The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1–11. 10.1177/160940690400300101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, E. L. , Fickley, C. E. , Maddux, L. , Krupnick, R. , Bahceci, E. , Paty, J. , & van Nooten, F. (2016). The patient perspective on living with acute myeloid leukemia. Oncology and Therapy, 4(2), 225–238. 10.1007/s40487-016-0029-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher, J. , Kirsten, L. , Butow, P. , & Sandoval, M. (2006). What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Social Science and Medicine, 62(10), 2565–2576. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, C. , Yuen, D. , Mischitelle, A. , Minden, M. D. , Brandwein, J. M. , Schimmer, A. , … Rodin, G. (2013). Symptom burden and supportive care in patients with acute leukemia. Leukemia Research, 37(7), 731–736. 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]