Abstract

Osteochondroma of the talus is a rare entity that can cause pain, swelling, restriction of movements, synovitis and tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS). We present three such cases with varying presentation. Case 1 presented with synovitis of the ankle along with a bifocal origin of the talar osteochondroma. Case 2 presented with TTS as a result of compression of the posterior tibial nerve. Case 3 presented with deformity of the foot. In all the three cases, the mass was excised en bloc and histologically proven to be osteochondroma. In case 3, the ankle joint was reconstructed with plate, bone graft and arthrodesis of the inferior tibiofibular joint. All the three cases had good clinical outcomes.

Keywords: orthopaedics, oncology

Background

Osteochondroma/exostosis is the most common primary benign tumour of the bone. The common sites for its location are metaphyses of long bones such as the distal femur, proximal tibia and proximal humerus.1 2 There are very few reported cases of solitary osteochondroma of the talus.3–5 We present a series of three cases of talar osteochondroma with different clinical presentations, surgical approaches and intraoperative findings.

Case presentation

Case 1

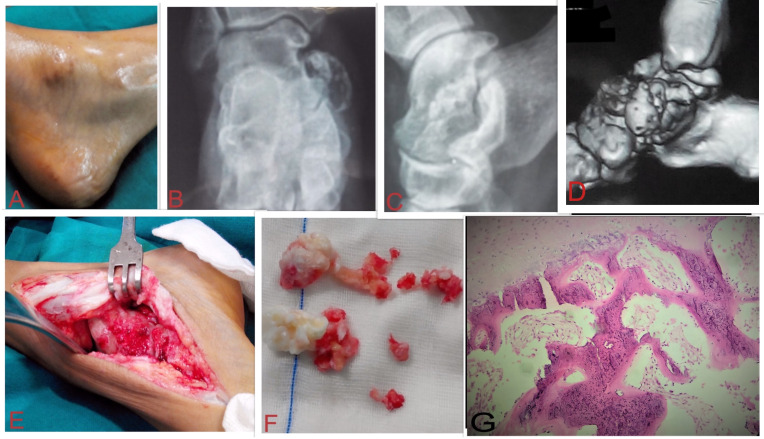

A 25-year-old woman presented with pain and swelling of the right ankle for 8 months. The pain worsened on walking and standing and lessened on taking rest. The swelling was peanut-sized initially and had gradually increased to its current size. Physical examination revealed a bony hard swelling of 4 cm×6 cm arising from the medial aspect of the dome of the talus (figure 1A) with normal overlying temperature and mild tenderness. The finger could not be insinuated between the talus and the swelling. There was boggy swelling around the ankle joint with synovial thickening. Ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion and inversion were restricted. X-rays showed two bony outgrowths—one from the dome of the talus on the medial aspect and the other from the junction of the head and neck on the medial aspect of the talus (figure 1B, C). The tibiotalar, subtalar and talonavicular joint spaces and surrounding bones were normal. These radiographs suggested the medullary continuity of the bony mass with the talus, suggesting osteochondroma. The imaging findings were confirmed on CT scan (figure 1D). MRI could not be done as the patient was claustrophobic.

Figure 1.

Case 1:(A) Bony swelling over the medial aspect of the talus. (B–D) X-rays and 3D-reconstructed CT scanshowed two bony outgrowths, one from the dome of the talus on the medial aspect and the other from the junction of the head and neck on the medial aspect of the talus with medullary continuity. (E) Outgrowth with shiny cartilaginous cap exposed using the anteromedial approach. (F) Excised tumour. (G) Histopathology showed enchondral ossification at the junction of bone and cartilage.

After informed consent, the patient was operated for excision of the exostoses. An anteromedial curvilinear incision was given starting 8 cm proximal and extending till 4 cm distal to the medial malleolus. The outgrowth was seen with shiny cartilage cap (figure 1E). The tumour was removed en bloc on the medial side and in pieces from the dome of the talus, along with some surrounding normal tissue (figure 1F).

The specimen was sent for histopathological examination which confirmed it to be osteochondroma of the talus. There was enchondral ossification at the junction of bone and cartilage (figure 1G). No signs of malignant transformation were seen. Postoperatively, the patient was immobilised for 4 weeks after which non-weight-bearing crutch walking was started and ankle movements were encouraged.

Case 2

A 12-year-old boy presented with gradually increasing swelling over the left ankle for 3 years, pain for 6 months and numbness in the first three toes for 6 months. Physical examination revealed a bony hard swelling of 3 cm×4 cm arising from the posteromedial aspect of the talus. Dorsiflexion was completely restricted and plantar flexion was possible till 20°. Pain exacerbated on inversion stress test. There was numbness in the first, second and third toes with no motor loss. Pressure applied behind the medial malleolus with two fingers for 30 s with forced inversion of the ankle led to tingling sensations in the first three toes. X-rays showed a bony protrusion from the posteromedial aspect of the body of the talus (figure 2A, B). CT scan confirmed its location and showed the medullary continuation of the tumour with the talus (figure 2C). MRI was suggestive of bony protrusion from the dome of the talus with marrow oedema at the superior margin of the calcaneum, the dome of the talus, and lower epiphysial surface of tibia and fibula (figure 2D). Retrocalcaneal loose bodies, and ankle joint effusion and synovial thickening were present.

Figure 2.

Case 2: (A-C) X-rays and CT scan showed a bony protrusion from the posteromedial aspect of the body of the talus with medullary continuation. (D) MRI (STIR/T2 fat sat) showed bony protrusion from the dome of the talus with marrow oedema at the superior margin of the calcaneum, the dome of the talus and lower epiphysial surface of tibia and fibula. (E) Histopathology showed disorganised cancellous bone with cartilaginous cap and focal vascular proliferation. (F) Healed posteromedial surgical scar. (G) Postoperative X-ray. STIR, short tau inversion recovery.

After informed consent, an en bloc excision of the tumour using the posteromedial approach to the ankle joint was done. Intraoperatively, the tumour was found to be compressing the posterior tibial nerve. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of osteochondroma of the talus. It showed disorganised cancellous bone with cartilaginous cap and focal vascular proliferation (figure 2E).

Case 3

An 18-year-old woman presented with swelling over the left ankle for 2 years, and pain and restricted ankle motion for 8 months. The pain was dull aching, and increased with activity and got relieved by rest. The left ankle was deformed. Physical examination revealed a 4 cm×3 cm bony hard swelling over the lateral aspect of the ankle joint which could be palpated both anteriorly and posteriorly to the lateral malleolus (figure 3A). Dorsiflexion of the ankle was possible till 5° and plantar flexion till 10°. The medial arch was increased and the foot appeared to be inverted. There was heel varus on weight-bearing. X-rays showed a bony swelling arising from the anterolateral aspect of the talus and impinging on the fibula (mass effect) (figure 3B, C). CT scan confirmed the location of the swelling and the continuity of its medullary cavity with the parent bone (figure 3D). Joint space was obliterated with no tibiofibular overlap. The ankle mortise was disrupted. MRI was not done due to the stainless steel implant in her opposite tibia.

Figure 3.

Case 3: (A) Swelling over the lateral aspect of the ankle. (B–D) X-rays and CT showed bony swelling arising from the anterolateral aspect of the talus with medullary continuity which was impinging on the fibula. (E) Exposure of the tumour using the posterolateral approach. (F) Excised tumour. (G) Histopathology showed cellular cartilaginous area adjacent to woven bone. (H) Reconstruction of the ankle joint using a one-third fibular plate and cortical screws and arthrodesis of the inferior tibiofibular joint using screws through the plate and bone graft.

The aim of surgery in this patient was excision of the tumour, reconstruction of the ankle joint and a plantigrade foot. A posterolateral incision starting 6 cm proximal from and extending till 2 cm distal to the fibular tip was made. The fibula was osteotomised 5 cm proximal to the tip of the lateral malleolus and everted. The tumour arising from the talus was visible with its shiny cartilaginous cap (figure 3E). En bloc excision of the tumour was done and a part of it was removed from the anterolateral aspect of the talus (figure 3F). For reconstruction, translateral malleolar approach was used. An osteotomy was made 1.5 cm proximal to the tip of lateral malleolus to correct the pressure effect. The ankle joint was reconstructed using a one-third fibular plate and cortical screws, and Ethibond where the screws were not giving purchase. The inferior tibiofibular joint was arthrodesed using screws through the plate and bone graft (figure 3H). This novel technique of reconstruction of ankle joint has not been used in any previous case of talar osteochondroma. Histopathology confirmed it to be osteochondroma of the talus. Cellular cartilaginous area was present adjacent to woven bone (figure 3G). Postoperatively, the limb was kept in an anteroposterior plaster slab. The stitches were removed at 2 weeks.

Outcome and follow-up

Case 1: At the 2-year follow-up, the patient had painless, improved ankle motion.

Case 2: At the 2-year follow-up, the patient had normal ankle range of motion with no tingling or numbness, and a well-healed scar (figure 2F). However, his left foot size was smaller compared with the right foot. His left footwear was one size smaller than the right.

Case 3: At the 2-year follow-up, the foot was plantigrade with dorsiflexion possible till 5° and plantar flexion till 30°. There was no pain on weight-bearing and the patient could perform activities of daily living without any difficulty.

Discussion

Osteochondroma is the most common benign tumour of the bone and is generally seen in the young and adolescent group. The pathoanatomy is not clear. It is thought to be a hamartomatous proliferation of bone and cartilage. Some state it to be arising from growth plate cartilage that grows through the cortex by endochondral ossification under the periosteum.6 The most common sites are around the knee (proximal tibia, distal femur) and proximal humerus.4 7 Osteochondroma of tarsal bones is rare and of talus is even rarer.6 Osteochondroma of the talus was reported in 1984 by Fuselier et al.8 Talar osteochondromas are more common in males (85%).3

Talar osteochondromas are usually asymptomatic but may present with pain, swelling, deformity, tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS), restricted ankle movements, synovitis, numbness of toes and loose bodies.5 We had different presentations in the three cases. Case 1 presented with synovitis around the ankle along with pain, swelling and restricted ankle movements. Case 2 presented with TTS. He had initially presented with swelling around the anteromedial and posterior aspect of the ankle joint. Later on, he had restriction of movements and compression symptoms of posterior tibial nerve on standing and prolonged walking. Eventually, this patient had one size smaller foot on the affected side. As the lesion was causing pressure effect on the growth plate and metaphyseal area, the growth of bone (longitudinal) might have been restricted leading to a decrease in the foot size.

Radiologically, osteochondroma is visualised as a protrusion from the talus in a pedunculated or sessile form. CT scan helps to determine the cortical and medullary continuity of the swelling with talus. MRI is done for better characterisation of the lesion, capped cartilage, soft tissue and neurovascular involvement.9 In our case series, the radiological features were characteristic of talar osteochondroma. Case 1 was unusual because the osteochondroma had a bifocal origin, one arising from the talar body on the anteromedial aspect and another from the medial side at the head–neck junction.

If the bony mass is asymptomatic, prophylactic surgery is not indicated. Surgery is indicated for pain, disturbance of growth, restricted range of motion of the ankle joint, bursitis, loose bodies, peduncle fracture and compression of the neurovascular bundle.10–14 The indications in our case series were pain, decreased ankle range of motion and disturbance of growth. The ankle joint was reconstructed in case 3. Ankle reconstruction following excision of talar osteochondroma has not been previously discussed in the literature. There were important and relevant intraoperative findings in each case. In case 1, besides the bifocal origin of the osteochondroma, there were lots of loose bodies and synovial thickening. In case 2, there were few loose bodies, one of which was adherent to and compressing the posterior tibial nerve. In case 3, the lateral malleolus was deformed due to the pressure effect of the tumour. All patients had painless, fair ankle motion at follow-up with no recurrence.

Patient’s perspective.

Case 1: Initially, the ankle swelling was small in size and I thought that it would go away. But gradually it started to grow and my ankle started getting stiff. I decided to go to the doctor where, after investigations, I was told that it was a benign tumour which needed removal. After surgery, the swelling and pain went away, and now I have no problems in walking, running or squatting.

Father of case 2: Our son had this ankle swelling for a few years but when it started paining and part of his foot started getting numb, we decided to get it checked. We were informed that it was an osteochondroma, which is a tumour of the bone, and it was pressing on the adjacent nerve. We were advised for excision of the tumour. After surgical removal, his symptoms subsided and he resumed school. But gradually his left foot became smaller than his right. The doctors told us that it was probably due to disturbed growth because of the tumour. We are aware that our son needs to be under follow-up to look for any recurrence of the tumour.

Case 3: I was not bothered much by the ankle swelling initially. But gradually it started aching and I could not move my ankle fully. My foot also started to bend inwards. The doctors, after getting the imaging, advised me for surgery. After discussing with my family members, I decided to go ahead with it. The tumour was excised and they also put a plate and bone graft. Gradually after surgery, the pain went away. Although I still cannot move my ankle fully, but I can do all my activities without any difficulty.

Learning points.

Osteochondroma of the talus is a rare entity and can present with pain, swelling, deformity, tarsal tunnel syndrome, restricted ankle movements, synovitis, numbness of toes and loose bodies.

Radiologically, it is visualised as bony protrusion arising from the talus with cortical and medullary continuity.

Surgery is indicated for pain, disturbance of growth, restricted range of motion of the ankle joint, bursitis, loose bodies, peduncle fracture and compression of the neurovascular bundle.

Surgical approach used depends on the location of the talar osteochondroma.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK, IKD and AKJ had the idea of the article, wrote the manuscript and were involved in patients care. PS did the literature search and wrote the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bovée JVMG. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:3. 10.1186/1750-1172-3-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khurana J, Abdul-Karim F. Osteochondroma. World Health Organization classification of tumours : Fletcher C, Krishnan Unni K, Mertens F L, Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. IARC press, 2002: 234–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galanis V, Georgiadi K, Balomenos V, et al. Osteochondroma of the talus in a 19-year-old female: a case report and review of the literature. Foot 2020;42:101635. 10.1016/j.foot.2019.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulkarni AG, Kulkarni GK. Paraarticular osteochondroma of talocalcaneal joint: a case report. Foot 2004;14:210–3. 10.1016/j.foot.2004.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suranigi S, Rengasamy K, Najimudeen S, et al. Extensive osteochondroma of talus presenting as tarsal tunnel syndrome: report of a case and literature review. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2016;4:269–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marco RA, Gitelis S, Brebach GT, et al. Cartilage tumors: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000;8:292–304. 10.5435/00124635-200009000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai A, Mitani S, Okuda K, et al. Ankle tumor in a 5-year-old boy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;406:308–16. 10.1097/00003086-200301000-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuselier CO, Binning T, Kushner D, et al. Solitary osteochondroma of the foot: an in-depth study with case reports. J Foot Surg 1984;23:3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, et al. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2000;20:1407–34. 10.1148/radiographics.20.5.g00se171407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottner F, Rodl R, Kordish I, et al. Surgical treatment of symptomatic osteochondroma. A three- to eight-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003;85:1161–5. 10.1302/0301-620x.85b8.14059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karakaş K, Perçin S, Kıs M. A case of fracture through the Pedunculated osteochondroma. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2000;34:96–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gür S, Altınel E, Gelen T, et al. Osteochondroma (fracture in osteochondroma, villonoduler synovitis in bursa). Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 1996;30:89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karakurt L, Yilmaz E, Varol T, et al. [Solitary osteochondroma of the elbow causing ulnar nerve compression: a case report]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2004;38:291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahveci R, Ergüngör MF, Günaydın A, et al. Lumbar solitary osteochondroma presenting with cauda equina syndrome: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2012;46:468–72. 10.3944/AOTT.2012.2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]