Abstract

Coronary artery angiography has many well-documented complications. Acute pancreatitis is a rarely described complication with potentially life-threatening repercussions. This article reports the case of a woman with acute pancreatitis that occurred within a few minutes after coronary artery angiography. Contrast agent toxicity and cholesterol emboli are the two mechanisms involved in the occurrence of acute pancreatitis after coronary artery angiography.

Keywords: Interventional cardiology, pancreatitis

Background

Coronary artery disease is the most common cardiovascular disease. It is also the leading cause of death in Switzerland.1 Approximately 23 000 diagnostics and/or therapeutic coronary artery angiographies were performed in Switzerland in 2016. This rate is rising steadily, with an average of approximately 1000 additional angiographies per year.2

Access point complications (infection and pseudoaneurysm), cardiac complications (arrhythmias, dissection of the coronary arteries and stenosis of the stent), hypersensitivity to contrast agent, acute renal failure and cholesterol embolism are well-documented complications.

In this report, we describe a case of severe pancreatitis following coronary angiography and discuss its possible physiopathology.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old female patient was admitted to hospital for elective coronary angiography motivated by septal hypokinesis visualised on transthoracic cardiac ultrasound. This examination was performed 3 months prior to admission as a part of the assessment of a transient cerebral ischaemic attack. On admission, she reported dyspnoea on exertion without chest pain. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, history of kidney lithiasis and gallbladder lithiasis requiring cholecystectomy at the age of 49 years, and the cited transient ischaemic attack. She reported occasional alcohol consumption (one glass of wine every month). There was no reported abdominal pain or recent abdominal trauma. Family history did not include recurrent or childhood pancreatitis. Current medications were acetylsalicylic acid, atorvastatin, candesartan, amlodipine, levothyroxine and cholecalciferol. Through a radial approach, 225 mL of iodixanol contrast agent (Visipaquem) was injected. During the coronary artery angiography, tritroncular coronary disease was revealed, requiring the placement of two active stents on the right coronary artery. Intermediate stenosis of the interventricular artery will be treated in a second stage. During a scan time of 18 min, the patient received a total of 7000 IU of unfractionated heparin, 5 mg verapamil, 5 mg adenosine and sedation with 2 mg midazolam and 2 mg morphine.

A few minutes after the procedure, she experienced sudden epigastric pain of intensity 8/10, with radiation to the back associated with vomiting food without haematemesis. She was, therefore, admitted to the internal medicine department for further investigation.

On physical examination, vital signs were normal, and the body mass index was 29 kg/m2. The right wrist showed no haematoma and radial pulse was present. Abdominal examination showed tenderness in the epigastrium with mild guarding. No jaundice was noted. The remainder of the examination, including cardiopulmonary examination, was unremarkable.

Investigations

Laboratory studies showed a leucocyte count of 20×109/L with a C reactive protein of 22 mg/L. The serum lipase was elevated at 267 U/L. Liver tests showed cholestasis without significant cytolysis (γ-glutamyltranspeptidase 173 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 119 U/L, total bilirubin 4 μmol/L, aspartate aminotransferase 43 U/L and alanine aminotransferase 56 U/L). Serum creatinine level was within normal range. Corrected calcium, triglycerides and IgG4 were within the normal range. Lipid profile (low-density lipoprotein 1.99 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein 2.5 mmol/L and total cholesterol 3.8 mmol/L) was within normal range too.

Electrocardiogram showed a regular sinus rhythm without any repolarisation disorder.

Abdominal ultrasound performed immediately showed biliary tract ectasia probably related to the history of cholecystectomy. There were no calculi visualised on the cholangio-MRI performed after 7 days. An abdominal contrast-enhanced CT performed after 48 hours of the presentation showed acute Balthazar C pancreatitis with necrosis within the head and uncinate process, and a necrotic collection along the right paracolic gutter (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abdominal scan showing an area of necrosis (☆) within the head of the pancreas.

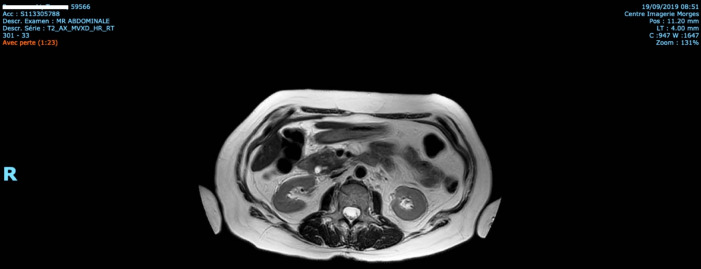

The 2-month control cholangio-MRI showed no obstructive calculi, stable bile duct ectasia and also excluded a tumour of the pancreas (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Abdominal MRI showing bile duct ectasia.

Diagnosis of Balthazar C pancreatitis of undetermined origin was retained.

Treatment

A supportive treatment was initiated with intravenous hydration and WHO level II analgesia. The patient fasted for 5 days (abdominal pain and nausea) with a gradual return to a low-fat diet.

Outcome and follow-up

The evolution was complicated by fever up to 38.5°C persisting for 5 days without haemodynamic instability. Laboratory studies showed accentuation of the inflammatory syndrome (C reactive protein up to 204 mg/L). The patient received antibiotics for a total duration of 14 days (ceftriaxone/metronidazole for 7 days and then ciprofloxacin/metronidazole), without microbiological evidence of infection. There was no organ dysfunction, cholestasis remained stable and the lipase decreased progressively with biological monitoring over 3 days. Hospitalisation lasted 3 weeks.

Six months later, the patient underwent another coronary angiography due to new-onset chest pain, this time without further complication. The contrast product was the same, but at a lower dosage than the first time (160 mL).

Discussion

Acute pancreatitis has many aetiologies, the two most common being alcohol and biliary obstruction (40% of cases each). Other obstructive, post-traumatic, metabolic, drug, infectious, autoimmune, ischaemic and genetic causes are less common (table 1). The aetiology is idiopathic in 10% of cases.3 4

Table 1.

Aetiologies of acute pancreatitis

| Obstructive causes | Biliary stones in choledochus Tumour (head of pancreas, Vater’s ampulla, bile duct and duodenum) Choledocian cyst and choledocele Periampullary duodenal diverticulum Pancreas divisum/annular pancreas Dysfunction of the Oddi sphincter |

| Toxic | Alcohol Scorpion and spider venom |

| Trauma/surgery | Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography Blunt trauma to the abdomen Cardiac surgery |

| Metabolic disorders | Hypertriglyceridaemia Hypercalcaemia |

| Infections | Bacteria: Mycoplasma, Legionella, Leptospira and Salmonella Viruses: Mumps, Coxsackie, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, HIV and hepatitis B virus Parasites: Ascaris, Cryptosporidium and Toxoplasma Fungus: Aspergillus |

| Drugs | Azathioprine, mercaptopurine, didanoside, pentamidine, sulfonamide, tetracyclines, furosemide, oestrogens, valproic acid, aminosalicylates and steroids |

| Autoimmune | Hyper-IgG4 syndrome Vasculitis (systemic lupus erythematosus and periarteritis nodosa) |

| Ischaemic | Hypovolemic shock |

| Mutations | PRSS1 (protease, serine 1) SPINK1 (serine protease inhibitor kazal type 1) CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) |

| Idiopathic |

The hypothesis of a lithiasis migration could not be formally excluded. However, the absence of lithiasis detected on the first ultrasound scan performed immediately after the procedure and the stability of the MRI performed 7 and 72 days later stand against this hypothesis. On the other hand, the temporal relationship between the artery coronarography and the onset of pain is striking.

In rare cases (<5%), drugs are incriminated, including atorvastatin and angiotensin II receptor antagonist, that the patient was taking. This hypothesis seems unlikely in the absence of recurrence or clinical deterioration with the continuation of these medications. Another risk factor that may contribute to the severity of pancreatitis in this patient is being overweight.

To the best of our knowledge, 10 cases of acute pancreatitis following coronary angiography have been reported in the literature.5–7 It is worth noting that these case reports describe abdominal symptoms appearing between H0 and H48 post procedure.

There are two probable physiopathological mechanisms underlying pancreatitis after coronary artery angiography. The first is thought to be related to the formation of cholesterol emboli during catheterisation, while the second concerns the direct toxicity of the contrast material. It may induce inflammation within the pancreas through the activation of NF-κB, calcium signalling pathways and cellular calcineurin as recently illustrated in an experimental model with mice.7 8 Moreover, it may alter the pancreatic microcirculation due to its hyperviscosity, but this mechanism remains controversial.9 10

We searched and excluded signs of clinically visible cholesterol emboli, both through laboratory findings (absence of eosinophilia and renal failure) and on eye fundus examination. Yet, the gold standard for this pathology remains cutaneous or renal biopsy. As these procedures were not performed in our patient, we might not formally exclude it.

The administered product consists of a non-ionic iodinated contrast medium (ie, the iodine is bound to an organic compound) of low osmolarity (290 mOsm/kg H2O), water-soluble, with a concentration of 320 mg/mL. It is worth noting that the same type of contrast agent was used in 2 of the 10 cases. In the other cases, the contrast product was not specified. Dosage of contrast material used in the other cases described ranged from 80 to 160 mL. During coronary angiography with stenting, 80–120 mL are used on average. In our case, the patient received two times the dose used on average. Therefore, an adverse drug reaction (type A), dose-dependant, is possible. However, given the rarity of this reaction in the literature, we cannot definitely conclude on this. Finally, an adverse drug reaction, idiosyncratic (type B), seems unlikely because the patient did not present recurring pancreatitis after a second coronary angiography 6 months later realised with the same contrast product.

Learning points.

In case of digestive symptoms occurring within a few hours post coronary angiography, acute pancreatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Coronarography-induced pancreatitis may be severe and can result in prolonged hospitalisation.

Contrast agent toxicity and cholesterol emboli are the two mechanisms involved in this complication.

Footnotes

Contributors: JK: Drafting the article, conception and design, acquisition of data and interpretation of data. TV: Revising it critically for important intellectual content, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved, and drafting the article. JB: Revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version published. LU: Revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version published. JK and TV: Contributed equally to this paper as first authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Office fédérale de la statistique Causes de décès spécifique. Available: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/etat-sante/mortalite-causes-deces/specifiques.html#par_text [Accessed 25 May 2020].

- 2.Fondation Suisse de Cardiologie Chiffres et données sur les maladies cardio-vasculaires en Suisse, 2016. Available: https://www.swissheart.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Swissheart/Bilder_Inhalt/5.0_Ueber_uns/5.1_Aufgaben_u_Aktivitaeten/Chiffres_et_donnees.pdf [Accessed 25 May 2020].

- 3.Windisch O, Raffoul T, Hansen C, et al. Pancréatite aiguë : quelles nouveautés dans la prise en charge ? Rev Med Suisse 2017;13:1240–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santhi Swaroop Vege UpToDate [Internet]. Etiology of acute pancreatitis. Available: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-of-acute-pancreatitis [Accessed 25 May 2020].

- 5.Gorges R, Ghalayini W, Zughaib M. A case of contrast-induced pancreatitis following cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol 2013;25:E203–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajimaghsoudi M, Zeinali F, Mansouri M, et al. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis following coronary artery angiography: a case report. ARYA Atheroscler 2017;13:156–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orvar K, Johlin FC. Atheromatous embolization resulting in acute pancreatitis after cardiac catheterization and angiographic studies. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1755–61. 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420150131013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin S, Orabi AI, Le T, et al. Exposure to radiocontrast agents induces pancreatic inflammation by activation of nuclear factor-κB, calcium signaling, and calcineurin. Gastroenterology 2015;149:753–64. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kheda M, Brenner L, Riggans D, et al. Pancreatitis following administration of iodixanol in patients on hemodialysis: a pilot study. Clin Nephrol 2010;73:381–4. 10.5414/CNP73381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plock JA, Schmidt J, Anderson SE, Sarr MG, et al. Contrast-Enhanced computed tomography in acute pancreatitis: does contrast medium worsen its course due to impaired microcirculation? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2005;390:156–63. 10.1007/s00423-005-0542-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]