Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although uterine contractions have a diurnal periodicity and increase in frequency during hours of darkness, data on the relationship between sleep duration and sleep timing patterns and preterm birth are limited.

OBJECTIVE

We sought to examine the relationship of self-reported sleep duration and timing in pregnancy with preterm birth.

STUDY DESIGN

In the prospective Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcome Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-be cohort, women completed a survey of sleep patterns at 6–13 weeks gestation (visit 1) and again at 22–29 weeks gestation (visit 3). Additionally, at 16–21 weeks gestation (visit 2), a subgroup completed a weeklong actigraphy recording of their sleep. Weekly averages of self-reported sleep duration and sleep midpoint were calculated. A priori, sleep duration of <7 hours was defined as “short,” and sleep midpoint after 5 AM was defined as “late.” The relationships among these sleep characteristics and all preterm birth and spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation were examined in univariate analyses. Multivariable logistic regressions that controlled for age and body mass index alone (model 1) and with additional covariates (race, smoking, insurance, and employment schedule) following a backward elimination process (model 2) were performed.

RESULTS

Of the 10,038 women who were enrolled, sleep survey data were available on 7524 women at visit 1 and 7668 women at visit 3. The rate of short sleep duration was 17.1% at visit 1 and 20.7% at visit 3. The proportion with a late sleep midpoint was 11.6% at visit 1 and 12.2% at visit 3. There was no significant relationship between self-reported short sleep and preterm birth across all visits. However, self-reported late sleep midpoint (>5 AM) was associated with preterm birth. Women with a late sleep midpoint (>5 AM) in early pregnancy had a preterm birth rate of 9.5%, compared with 6.9% for women with sleep midpoint ≤5 AM (P=.005). Similarly, women with a late sleep midpoint had a higher rate of spontaneous preterm birth (6.2% vs 4.4%; P=.019). Comparable results were observed for women with a late sleep midpoint at visit 3 (all preterm birth 8.9% vs 6.6%; P=.009; spontaneous preterm birth 5.9% vs 4.3%; P=.023). All adjusted analyses on self-reported sleep midpoint (models 1 and 2) maintained statistical significance (P<.05), except for visit 1, model 2 for spontaneous preterm birth (P=.07). The visit 2 objective data from the smaller subgroup (n=782) demonstrated similar trends in preterm birth rates by sleep midpoint status.

CONCLUSION

Self-reported late sleep midpoint in both early and late pregnancy, but not short sleep duration, is associated with an increased rate of preterm birth.

Keywords: pregnancy, preterm birth, sleep duration, sleep midpoint, sleep timing

Mounting experimental and epidemiologic data suggest that, among nonpregnant adults, sleep duration and timing contributes to physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing.1–4 There are particularly strong data that link short sleep duration and shift work, which is a risk factor for insufficient sleep and altered sleep timing, to type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.5,6 Similarly, in pregnancy, shorter sleep duration and later sleep timing have been linked to gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes mellitus.7–9

Although uterine contractions have a diurnal periodicity and increase in frequency during hours of darkness, data on the relationship of sleep duration and timing with preterm birth (PTB) are limited and inconsistent.10,11 Moore et al11 longitudinally studied the prelabor uterine contraction patterns in women with uncomplicated pregnancies, all of whom delivered at term. A significant nighttime clustering of uterine contractions occurred in the hours 8 PM to 8 AM, with 67.4% occurring at night. This diurnal pattern was not evident at <24 weeks gestation but became marked after that time, with a night-to-day ratio of 1.8:1 at 21–24 weeks gestation, 2.3:1 at 28–32 weeks gestation, and 2.0:1 at 38–40 weeks gestation. Some data suggest that disturbed maternal sleep and activity patterns may increase the risk of PTB.12,13 However, many studies have focused on shift work as the exposure and did not examine specifically the sleep and activity patterns that can arise from shift work.14–16

Our objective was to examine the relationship of self-reported sleep duration and timing in pregnancy with PTB in a large cohort of nulliparous women who had sleep assessments at multiple time points in pregnancy.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcome Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b). NuMoM2b was a prospective observational cohort study that was conducted at 8 clinical sites and was managed by a central data coordinating and analysis center.17 Nulliparous women were screened for eligibility in the first trimester of pregnancy and were eligible if they had a viable singleton gestation between 6 weeks+0 days gestation and 13 weeks+6 days gestation. Participants were seen at 3 study visits during pregnancy and 1 study visit at delivery. Study visits 1, 2, and 3 occurred during the following gestational age intervals, respectively: 6 weeks 0 days to 13 weeks 6 days; 16 weeks 0 days to 21 weeks 6 days; and 22 weeks 0 days to 29 weeks 6 days. At study visits 1 and 3, women completed a sleep questionnaire that included questions about the duration and timing of their sleep during the last month. At visit 2, a subset of women enrolled in the Sleep Duration and Continuity Study, an ancillary study of nuMoM2b. This subgroup of women was asked to measure sleep objectively over 7 days with a wrist actigraph, while keeping a subjective sleep log. An actigraphy recording was considered successful if there was a minimum of 5 days recorded, during which there was <4 hours of off-wrist time per a 24-hour period and no off-wrist signal during the time the subject indicated she was in bed. All actigraph files and sleep log data were transmitted securely to a central actigraphy reading center. Actigraphy data were analyzed with Actiware Sleep software (version 5.59; Respironics, Inc, Murrysville, PA). Data were processed through the Actiware Sleep scoring algorithm. The default scoring algorithm was set with 10 minutes of immobile time for sleep start, in reference to the set rest start, and 10 minutes of immobile time for sleep end, in reference to the set rest end. The complete actigraphy scoring and quality control protocol has been described previously.8 This study was approved the Institutional Review Board at each center. All women provided informed written consent before enrollment.

On the visit 1 and 3 sleep questionnaires, women were asked about the timing of their sleep on weekdays/ workdays and weekends with the use of the following 2 questions: “Not including naps, what time do you usually go to bed?” and “Not including naps, what time do you usually wake up?” In addition, women were asked to estimate how many minutes it usually takes for them to fall asleep at bedtime and how many minutes of wake time they typically have during a night’s sleep.“Calculated” sleep duration was estimated as the interval from bedtime to wake time minus the time it took to fall asleep and the time spent awake during the night. This was separately calculated for weekdays/ workdays and weekends. Quality assessments were done on the calculated sleep duration values for weekdays/ workdays and weekends with the use of the following question from the sleep questionnaire: “How many hours of sleep do you usually get per night?” If the reported sleep duration from this additional question was not within 2 hours of the calculated sleep duration, then the times that were used for the calculated sleep duration were run through a series of edit checks to identify and correct potential errors in the selection of AM or PM. If th calculated duration was still not within 2 hours of the reported duration after potential AM/PM errors were edited and the sleep duration was recalculated, then the calculated duration and the corresponding times were set to missing. Weekly average sleep duration was calculated as a weighted average of the weekday/workday and weekend sleep durations with the use of the following formula: (weekday/workday duration×5+weekend duration×2)/7. The midpoint of the sleep period for both weekdays and weekends was also calculated; the sleep start time accounted for the duration of time it took to fall asleep after initiation of bedtime. The weekly average sleep midpoint was calculated as a weighted average of the weekday/workday and weekend sleep midpoints with the use of the following formula: (weekday/ workday midpoint×5+weekend midpoint ×2)/7.

Sleep exposures

Based on previous data in nonpreg nant populations that detailed the relationship between sleep duration and health outcomes, a sleep duration of <7 hours was defined a priori as “short sleep duration.”18 A cutoff of later than 5 AM was defined a priori as a “late sleep midpoint.”19,20 Secondary analyses were also performed with sleep duration divided into 5 categories (<6 hours, 6 to<7 hours, 7 to <8 hours (referent), 8 to <9 hours and ≥9 hours) and with a separate examination of long sleep duration (≥9 vs <9 hours).

Primary outcomes

PTB was defined as delivery at <37 weeks gestation based on well-established dating criteria that included documented crown-rump length measurements by a certified nuMoM2b sonographer between 6 weeks+0 days gestation and 13 weeks+6 days gestation. Spontaneous PTB (sPTB) was a PTB that was due to premature labor or premature rupture of membranes, regardless of subsequent labor augmentation or cesarean delivery. SPTB was documented by chart abstraction by certified research personnel. For both the PTB and sPTB outcomes, pregnancy losses at <20 weeks gestation and pregnancy terminations were excluded.

Analytical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population by the primary dichotomous sleep exposures (sleep duration <7 hours, sleep midpoint >5 AM). Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the distribution of sleep duration and sleep midpoint by baseline demographic variables. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the association of sleep characteristics at all visits with PTB (all and spontaneous). Adjustment covariates chosen a priori were maternal age and prepregnancy body mass index, both of which were entered into regression models as continuous variables (model 1). If the relationship between the sleep exposure variable and the outcome was significant in model 1, an additional analysis was undertaken to consider additional covariates for adjustment. Specifically, a backward stepwise approach was taken to develop a model 2 for the reporting of adjusted odds ratios for the sleep exposure on outcome. Maternal age, body mass index, and a set of exploratory variables were entered in a model and then were evaluated as to whether they should stay in the model based on the significance of their association with the outcome (P<.10) and evidence of confounding on the association of sleep exposure variable and outcome. Exploratory variables were eliminated 1-by-1, by taking the least significant among those with P≥.10 and evaluating the change in the adjusted odds ratio relating the sleep exposure to the outcome with inclusion vs exclusion of the covariate. If exclusion of the exploratory variable resulted in an absolute change of ≥10% in the adjusted odds ratio for the sleep exposure on outcome, then the variable was retained, and the stepwise elimination process was halted. Otherwise the exploratory variable was excluded, and the process was repeated to consider other exploratory variables to be retained or eliminated from the reduced model. We finally arrived at a model 2 for the reporting of adjusted odds ratios for sleep exposure on outcome and for consideration of confounding. Exploratory variables that were considered for inclusion were race/ethnicity (categorized as white, black, Hispanic, Asian, or other), employment schedule (categorized as regular day shift, some form of shift work, or unemployed), insurance status (categorized as commercial insurance or other insurance), and smoking status (self-reported smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy). These variables were chosen given their reported associations with sleep duration and timing and PTB. For all analyses, women with chronic hypertension or pregestational diabetes mellitus were excluded.

All tests were 2-sided single-degree-of-freedom tests and were performed at a nominal significance level of α=.05. No correction was made for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted with SAS statistical software (version 9.3/9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

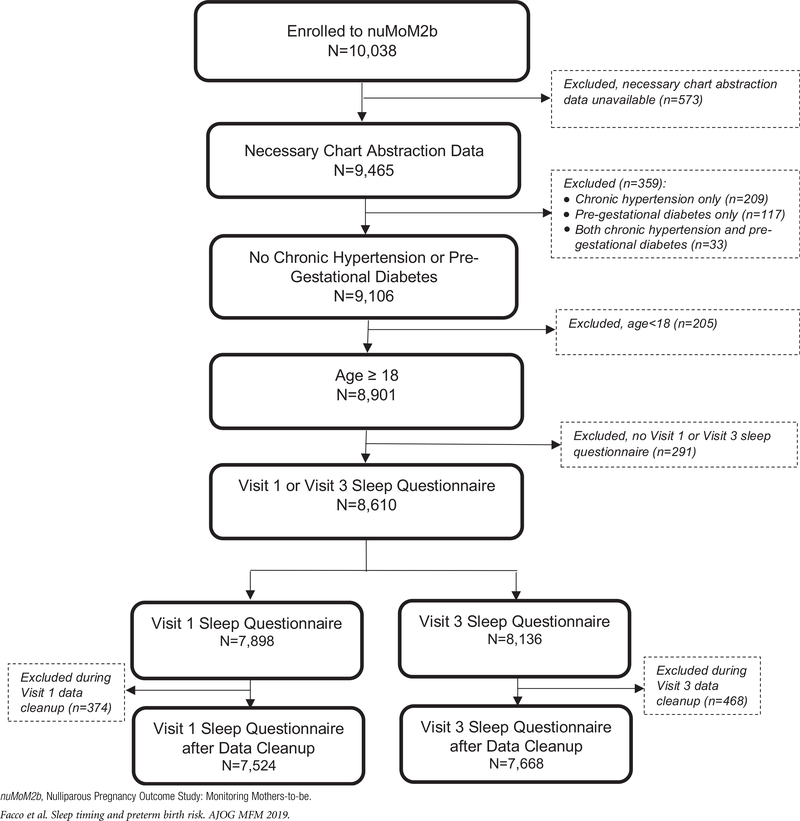

The nuMoM2b study enrolled 10,038 women; the characteristics of the study population have been described (Supplement Table 1).21 In summary, the mean age of women at entry into the study was 27.0 years (standard deviation, 5.7 years). Sixty percent (59.7%) of the women were non-Hispanic white; 14.2% were non-Hispanic black; 16.9% were Hispanic; 4.0% were Asian, and 5.1% were classified as other on race/ethnicity. After data cleaning, valid sleep survey data were available for 7524 women at visit 1 and for 7668 women at visit 3 (Figure 1). Nine-hundred one eligible women enrolled in the Sleep Duration and Quality ancillary study at visit 2, of whom 782 women (86.8%) had valid actigraphy recordings.

FIGURE.

Enrollment and inclusion in analysis

Questionnaire data at visit 1 and visit 3

The distribution of sleep duration and sleep midpoint at visits 1 and 3 are presented in Table 1, as are the associations between sleep duration and sleep midpoint with age, body mass index, race/ethnicity, insurance status, smoking status, and employment schedule.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of subjective sleep duration and sleep midpoint, overall and by demographic characteristics

| Variable | Visit 1: 6–13 weeks gestation (n=7524) | Visit 3: 22–29 weeks gestation (n=7668) |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration, hr | ||

| Overalla | 8.01 (1.44) | 7.86 (1.47) |

| Category, n (%) | ||

| <7 | 1286 (17.1) | 1590 (20.7) |

| ≥7 | 6238 (82.9) | 6078 (79.3) |

| Age, ya | ||

| 18–21 | 8.67 (2.22) | 8.58 (2.29) |

| 22–35 | 7.98 (1.33) | 7.80 (1.34) |

| >35 | 7.70 (1.24) | 7.53 (1.27) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2a | ||

| <25 | 8.04 (1.39) | 7.86 (1.40) |

| 25 to <30 | 8.01 (1.42) | 7.83 (1.48) |

| ≥30 | 7.95 (1.63) | 7.86 (1.68) |

| P valueb | .0005 | .4817 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 7.98 (1.29) | 7.80 (1.31) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 8.06 (2.21) | 8.11 (2.25) |

| Hispanic | 8.33 (1.85) | 8.12 (1.82) |

| Asian | 7.86 (1.27) | 7.75 (1.35) |

| Other | 7.95 (1.68) | 7.83 (1.64) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Insurance statusa | ||

| Commercial insurance | 7.95 (1.30) | 7.75 (1.27) |

| Other insurance | 8.39 (2.08) | 8.33 (2.13) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Smoking status in the 3 mo before pregnancya | ||

| Yes | 8.08 (1.86) | 7.99 (1.94) |

| No | 8.00 (1.38) | 7.83 (1.40) |

| P valueb | .1803 | .0016 |

| Employment schedulea | ||

| Regular day shift | 7.92 (1.19) | 7.75 (1.19) |

| Some form of shift work | 7.95 (1.77) | 7.86 (1.79) |

| Unemployed | 8.64 (1.97) | 8.36 (1.98) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Sleep midpoint, hr:min | ||

| Overalla | 3:14 (1:26) | 3:14 (1:28) |

| Category, n (%) | ||

| >5 am | 876 (11.6) | 936 (12.2) |

| ≤5 am | 6648 (88.4) | 6732 (87.8) |

| Age, ya | ||

| 18–21 | 4:06 (1:54) | 4:07 (1:56) |

| 22–35 | 3:08 (1:18) | 3:07 (1:20) |

| >35 | 2:58 (1:05) | 3:00 (1:03) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2a | ||

| <25 | 3:13 (1:22) | 3:14 (1:24) |

| 25 to <30 | 3:14 (1:29) | 3:14 (1:27) |

| ≥30 | 3:20 (1:39) | 3:15 (1:39) |

| P valueb | .0363 | .5650 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 3:04 (1:13) | 3:04 (1:13) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 3:50 (2:03) | 3:51 (2:06) |

| Hispanic | 3:45 (1:49) | 3:44 (1:46) |

| Asian | 3:22 (1:22) | 3:32 (1:17) |

| Other | 3:20 (1:46) | 3:27 (1:37) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Insurance statusa | ||

| Commercial insurance | 3:03 (1:11) | 3:03 (1:12) |

| Other insurance | 4:00 (1:53) | 4:00 (1:57) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Smoking status in the 3 mo before pregnancya | ||

| Yes | 3:45 (1:56) | 3:42 (1:53) |

| No | 3:10 (1:20) | 3:10 (1:23) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Employment schedulea | ||

| Regular day shift | 2:56 (1:01) | 2:56 (1:02) |

| Some form of shift work | 3:55 (2:06) | 3:54 (2:05) |

| Unemployed | 4:05 (1:42) | 4:01 (1:48) |

| P valueb | <.0001 | <.0001 |

Data are given as median (interquartile range)

Associated with Kruskal-Wallis tests

The associations of self-reported short sleep duration and late sleep midpoint with PTB that were ascertained by questionnaire (weighted average of weekday/weekend) are shown in Table 2. Self-reported short sleep duration at visit 1 was not associated with PTB or sPTB. Short sleep duration at visit 3 was associated with sPTB in univariate analyses but was no longer significant after we controlled for age and body mass index (model 1). Furthermore, in secondary analyses of different sleep duration cutoffs (<6 hours, ≥9 hours), no associations were observed between sleep duration and PTB or sPTB (Supplement Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for all preterm birth < 37 weeks and spontaneous preterm birth < 37 weeks according to subjective sleep assessments at visits 1 and 3

| Sleep characteristic categories | All preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation, estimate (95% confidence interval) | Spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation, estimate (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | Estimate (95% confidence interval) | n/N (%) | Estimate (95% confidence interval) | |||

| Crude odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio: model 1a | Crude odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio: model 1a | |||

| Visit 1 | ||||||

| Sleep duration (calculated), hr | ||||||

| <7 | 104/1284 (8.1) | 1.17 (0.94–1.47) | 1.15 (0.92–1.44) | 64/1284 (5.0) | 1.11 (0.84–1.46) | 1.11 (0.84–1.47) |

| ≥7 | 435/6226 (7.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 282/6225 (4.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| P value | .1598 | .2330 | .4797 | .4629 | ||

| Sleep midpoint | ||||||

| >5 am | 83/874 (9.5) | 1.42 (1.11–1.82) | 1.39 (1.08–1.80) | 54/873 (6.2) | 1.43 (1.06–1.93) | 1.45 (1.06–1.99) |

| ≥5 am | 456/6636 (6.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 292/6636 (4.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| P value | .0049 | .0113 | .0186 | .0193 | ||

| Visit 3 | ||||||

| Sleep duration (calculated), hr | ||||||

| <7 | 125/1587 (7.9) | 1.21 (0.98–1.49) | 1.18 (0.95–1.45) | 86/1586 (5.4) | 1.31 (1.02–1.68) | 1.28 (0.99–1.65) |

| ≥7 | 400/6071 (6.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 255/6071 (4.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| P value | .0710 | .1327 | .0360 | .0579 | ||

| Sleep midpoint | ||||||

| >5 am | 83/932 (8.9) | 1.39 (1.09–1.78) | 1.40 (1.08–1.81) | 55/932 (5.9) | 1.41 (1.05–1.90) | 1.48 (1.09–2.03) |

| ≥5 am | 442/6726 (6.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 286/6725 (4.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| P value | .0085 | .0100 | .0229 | .0130 | ||

Odds ratios are adjusted for age and body mass index.

There was, however, a consistent association between late sleep midpoint and PTB at both visits 1 and 3. At visit 1, women with a late sleep midpoint had a higher rate of PTB (9.5% vs 6.9%; P=.005) and of sPTB (6.2% vs 4.4%; P=.019). Comparable results were observed for women with a late sleep midpoint at visit 3 (all PTB: 8.9% vs 6.6%; P=.009; sPTB: 5.9% vs 4.3%; P=.023) After adjustment for age and body mass index in multivariable analysis, the association of PTB with late sleep midpoint at both visits 1 and 3 remained (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–1.80 for visit 1; adjusted OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.08–1.81 for visit 3). The same was true for sPTB (adjusted OR, 1.45;95% CI, 1.06–1.99 for visit 1; adjusted OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.09–2.03 for visit 3).

Given the results for sleep midpoint in model 1, we evaluated additional covariates using the backward stepwise method described earlier (model 2). Results of these analyses are presented in Table 3. All analyses maintained statistical significance, except for late sleep midpoint at visit 1 for sPTB (P=.07), and there was little evidence of confounding because the adjusted odds ratios changed by <10%.

TABLE 3.

Odds Ratios for all preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation and spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation

| Sleep characteristic | Preterm birth outcome | Model 2 covariates | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | Difference in odds ratio: model 1 vs model 2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1: sleep midpoint >5 am vs ≤5 am | All preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation | Age+body mass index+race+insurance | 1.34 (1.03–1.74) | .0285 | 3.80 |

| Spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation | Age+body mass index+insurance+smoking | 1.34 (0.97–1.85) | .0727 | 8.34 | |

| Visit 3: sleep midpoint >5 am vs ≤5 am | All preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation | Age+body mass index+insurance | 1.32 (1.01–1.72) | .0398 | 6.06 |

| Spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation | Age+body mass index +insurance | 1.38 (1.00–1.91) | .0477 | 7.30 |

Visit 2 objective sleep data

Seven hundred eighty-two women provided 5–7 days of objective sleep data (Table 4). As with the self-reported sleep data, no trends were observed in the relationship between objectively measured short sleep duration and PTB or sPTB. In contrast, the magnitude of associations of objectively measured sleep midpoint with both PTB and sPTB were similar to those noted for subjectively reported sleep midpoint, although the confidence intervals for the odds ratios included one, likely because of the smaller sample size. The rate of PTB was 9.5% for women with a late sleep midpoint compared with 5.8% in women with a sleep midpoint ≤5 AM (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 0.88–3.20), and the rate of sPTB were 5.4% vs 2.8% (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 0.83–4,58).

TABLE 4.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for all preterm birth at <37 weeks gestation and spontaneous preterm birth at <37 weeks gestationa

| Sleep characteristic categories | All preterm birth <37 weeks gestation | Spontaneous preterm birth <37 weeks gestation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | Crude odds ratio estimate (95% confidence interval) | Adjusted odds ratio model 1, estimate (95% confidence interval)b | n/N (%) | Crude odds ratio estimate (95% confidence interval) | Adjusted odds ratio model 1 estimate (95% confidence interval)b | |

| Sleep duration, hr | ||||||

| <7 | 16/218 (7.3) | 1.19 (0.65–2.21) | 1.19 (0.64–2.21) | 7/218 (3.2) | 0.95 (0.39–2.29) | 0.94 (0.39–2.28) |

| ≥7 | 35/563 (6.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 19/563 (3.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| P value | .5693 | .5821 | .9089 | .8962 | ||

| Sleep midpoint | ||||||

| >5 am | 14/148 (9.5) | 1.68 (0.88–3.20) | 1.61 (0.80–3.25) | 8/148 (5.4) | 1.95 (0.83–4.58) | 1.92 (0.77–4.79) |

| ≤5 am | 37/633 (5.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 18/633 (2.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| P value | .1125 | .1852 | .1241 | .1600 | ||

According to objective actigraphy assessment at visit 2

Adjusted for age and body mass index.

Comment

Principal findings

In this analysis, there was no relationship between self-reported short sleep duration, defined as < 7 hours per night, and PTB. In contrast, there was a consistent relationship between self-reported late sleep timing and PTB.

Results in context

Available data are inconsistent regarding the relationship between sleep duration and PTB, although the significant associations that have been reported typically have come from relatively smaller studies. In a single-center study in Seattle, WA, >1200 women at 14 weeks gestation, on average, were asked to report: “Since becoming pregnant, how many hours per night do you sleep.” This study found no differences in gestational age at delivery (categorized as <28, 28–36, 37–40, and >40 weeks gestation) by sleep duration.9 However, smaller studies have reported positive associations. In a case-control study from Peru, short sleep duration (≤6 hours) was associated significantly with spontaneous PTB at <37 weeks gestation (adjusted OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.11–2.19).12 A cross-sectional study from Greece observed a similar association.13 Although not directly measuring sleep duration, a large California database study found that, compared with women without a recorded sleep disorder diagnose, women with insomnia had nearly a 2-fold higher risk of early PTB at <34 weeks gestation (adjusted OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.6).22

Our data demonstrated a consiste relationship between self-reported late sleep midpoint (>5 AM) and PTB and sPTB both at visits 1 and 3. The relationships remained significant, with ORs of between 1.3 and 1.4, after we controlled for age and body mass index and largely after adjustment for other covariates. Although our analyses on the objectively measured sleep characteristics at visit 2 was limited by asample size(n=782) that was nearly one-tenth the size of that for the self-reported data, these objective data, although statistically nonsignificant, corroborated the strength of the association found with the self-reported data. This is consistent with a previously demonstrated strong correlation between objective and subjective sleep timing data in this cohort. The median difference between subjectively (daily diary concurrent with actigraphy) and objectively derived sleep midpoint at visit 2 was 2 minutes, and there was 94.3% agreement in categorizing sleep midpoint as late (>5 AM) or early (≤5 AM).23

Clinical implications

Later sleep timing has physiologic implications. For example, it can lead to increased exposure to artificial light at night and later meal timing, both of which can contribute to circadian misalignment. Circadian misalignment can occur when sleep and wakefulness behaviors do not occur at an appropriate time relative to the timing of the central circadian clock (hypothalamus) and/or relative to the external environment (light-dark cycle).

Most research regarding circadian timing and pregnancy outcomes has not examined sleep-timing patterns specifically but rather has focused on shift work as the specific exposure. I is known that certain forms of shift work may lead to sleep disruption and circadian misalignment. Shift work has been associated with poor health outcomes, especially obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in population-based studies of nonpregnant individuals.24–26 Data regarding shift work and its relationship with pregnancy outcomes has produced inconsistent conclusions for outcomes such as infertility, miscarriage, PTB, and lower birthweight. 14,15 One meta-analysis of 13 studies found no clear or statistically significant relationship between PTB and shift work. The authors noted a slightly elevated risk of PTB for women who reported long work hours (>40 hours/week; OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01–1.54).16 In a separate analysis of 16 studies, Bonzini et al14 found a pooled relative risk for PTB of 1.16 (95% CI, 1.00–1.33). These findings suggest that, even if it were to exist, the overall increased risk of PTB that is associated with shift work exposure per se is small.

However, data on shift work are difficult to interpret because many studies have not distinguished properly between different types of work, and it remains unknown whether it is the type of work or the timing of the shift that is the relevant exposure. Also, focusing on shift work ignores the fact that circadian disruption is not limited to those who are exposed to shift work. In fact, we have shown previously that pregnant women who report shift work and those who women who do not have a regular work schedule because of being unemployed are at the highest risk of having a late sleep midpoint.7 The present study was able to address these limitations by the use of the sleep midpoint as our exposure variable and also by inclusion of a variable for employment schedule (regular day shift, some form of shift work, or unemployed) in our model 2 stepwise regression.

Research implications

Future work to further the understanding of circadian biologic evidence in pregnancy may provide important opportunities for useful risk stratification and the development of novel therapies for the treatment and prevention of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Other experimental data support the notion that circadian rhythm misalignment may contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes. In mammals, the circadian timing system comprises a “master clock” located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus that can influence peripheral clocks in virtually every tissue. The molecular regulation of the biologic clock is based on the transcriptional/translational feedback loop of a network of “clock” genes (ie, Clock, Bmal1, Per1, Per2, Per3, Cry1, and Cry2). These genes are also expressed rhythmically in the human placenta.27 Rhythmic placental production of hormones and cytokines has also been observed.28 In a mouse model of environmental disruption of circadian rhythms with the use of repeated shifts of the light-dark cycle, animals that wee exposed to phase delays and phase advancements had reductions in full-term pregnancy success29.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. The nuMoM2b cohort is a geographically and demographically diverse study population. We prospectively ascertained subjective sleep duration and timing variables at 2 different time points in pregnancy, which limited the potential for ascertainment or recall bias. Additionally, we collected objective data on a subgroup of women, and these data supported the findings that were derived from the subjective sleep data. We were limited, however, in regards to the analysis of objective data because of the relatively smaller sample size. Additionally, our distributions of sleep duration and midpoint did not allow us to examine more extreme sleep phenotypes (eg, sleep duration <6 hours, extreme day-to-day sleep midpoint variability) meaningfully as potential risks factors for PTB. Finally, we recognize that sleep midpoint tendencies differ by various demographic factors. We recognize that, although our sample was racially, economically, and socially diverse, it was composed of only nulliparous women; we did exclude women with chronic hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. This limits the generalizability of our analysis. We acknowledge that, by the nature of the observational design of this study, we are not able to account fully for all confounding and mediating factors, and causality cannot be known. We recognize that observed effects may be mediated by medical, social, physiologic, and environmental factors.

Conclusion

We found that self-reported late sleep midpoint (>5 AM) in both early and late pregnancy, but not short sleep duration (<7 hours), is associated with an increased rate of PTB and sPTB in nulliparous women. An increased understanding of the role of circadian biologic evidence in pregnancy may provide important opportunities for useful risk stratification and the development of novel therapies for the treatment and prevention of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Supplementary Material

AJOG MFM at a Glance

Why was this study conducted?

This study was conducted to examine the relationship of subjectively assessed sleep duration and timing in pregnancy with preterm birth.

Key findings

Self-reported late sleep midpoint (≥5 AM) in both early and late pregnancy, but not short sleep duration, is associated with an increased rate of preterm birth.

What does this add to what is known?

There is limited research regarding circadian rhythms and pregnancy outcomes. Most studies have not specifically examined sleep timing patterns but rather have focused on shift work during pregnancy as the exposure variable. The present study describes an association between late sleep timing and preterm birth. It addresses limitations of previous reports by the use of sleep midpoint as the exposure variable and by the examination of the relationship between this exposure and preterm birth and considers potential confounders that include employment schedule.

Acknowledgments

Supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: U10-HL119991; U10-HL119989; U10-HL120034; U10-HL119990; U10-HL120006; U10-HL119992; U10-HL120019; U10-HL119993; and U10-HL120018; R01HL105549. Supplemental funding for this analysis was provided by the National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research through U10-HL119992; support was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciencese UL-1-TR000124, UL-1-TR000153, and UL-1-TR001108.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Registration number NCT02231398.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

P.P.Z. serves as a consult to Philips Respironics, the makers of the actiwatches that were purchased for use in this study. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Francesca L. Facco, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA.

Corette B. Parker, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Shannon Hunter, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Kathryn J. Reid, Department of Neurology, Gynecology-Maternal Fetal Medicine & Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Phyllis P. Zee, Department of Neurology, Gynecology-Maternal Fetal Medicine & Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

Robert M. Silver, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah and Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, UT.

Grace Pien, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Judith H. Chung, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA.

Judette M. Louis, University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa FL.

David M. Haas, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN.

Chia-Ling Nhan-Chang, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Hyagriv N. Simhan, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA.

Samuel Parry, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Ronald J. Wapner, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN.

George R. Saade, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Texas Medical Branch, University of Texas, Galveston, TX.

Brian M. Mercer, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH.

Melissa Bickus, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA.

Uma M. Reddy, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD.

William A. Grobman, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology-Maternal Fetal Medicine & Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Morselli L, Leproult R, Balbo M, Spiegel K. Role of sleep duration in the regulation of glucose metabolism and appetite. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;24:687–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knutson KL. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;24:731–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullington JM, Haack M, Toth M, Serrador JM, Meier-Ewert HK. Cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009;51: 294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zee PC, Turek FW. Sleep and health: everywhere and in both directions. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1686–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.St-Onge MP, Grandner MA, Brown D, et al. Sleep duration and quality: impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;134:e367–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ 2016;355:i5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Facco FL, Grobman WA, Reid KJ, et al. Objectively measured short sleep duration and later sleep midpoint in pregnancy are associated with a higher risk of gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:447.e1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid KJ, Facco FL, Grobman WA, et al. Sleep during pregnancy: the nuMoM2b Pregnancy and Sleep Duration and Continuity Study. Sleep 2017;40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams MA, Miller RS, Qiu C, Cripe SM, Gelaye B, Enquobahrie D. Associations of early pregnancy sleep duration with trimester-specific blood pressures and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Sleep 2010;33:1363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore TR. Patterns of human uterine contractions: implications for clinical practice. Semin Perinatol 1995;19:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore TR, Iams JD, Creasy RK, Burau KD, Davidson AL. Diurnal and gestational patterns of uterine activity in normal human pregnancy: the Uterine Activity in Pregnancy Working Group. Obstet Gynecol 1994;83:517–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kajeepeta S, Sanchez SE, Gelaye B, et al. Sleep duration, vital exhaustion, and odds of spontaneous preterm birth: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Micheli K, Komninos I, Bagkeris E, et al. Sleep patterns in late pregnancy and risk of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction. Epidemiology 2011;22:738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonzini M, Palmer KT, Coggon D, Carugno M, Cromi A, Ferrario MM. Shift work and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis of currently available epidemiological studies. BJOG 2011;118: 1429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stocker LJ, Macklon NS, Cheong YC, Bewley SJ. Influence of shift work on early reproductive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124: 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Melick MJ, van Beukering MD, Mol BW, Frings-Dresen MH, Hulshof CT. Shift work, long working hours and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2014;87:835–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. NuMoM2b Sleep-Disordered Breathing study: objectives and methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:542.e1–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consensus Conference Panel, Watson NF, Badr MS, et al. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:931–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Juda M, et al. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med Rev 2007;11:429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roenneberg T, Allebrandt KV, Merrow M, Vetter C. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr Biol 2012;22:939–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas DM, Parker CB, Wing DA, et al. A description of the methods of the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: monitoring mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:539.e1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felder JN, Baer RJ, Rand L, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Prather AA. Sleep disorder diagnosis during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facco FL, Parker CB, Hunter S, et al. Association of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes With Self-Reported Measures of Sleep Duration and Timing in Women Who Are Nulliparous. J Clin Sleep Med 2018;14:2047–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gan Y, Yang C, Tong X, et al. Shift work and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Occup Environ Med 2015;72: 72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen AB, Stayner L, Hansen J, Andersen ZJ. Night shift work and incidence of diabetes in the Danish nurse cohort. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monk TH, Buysse DJ. Exposure to shift work as a risk factor for diabetes. J Biol Rhythms 2013;28:356–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez S, Fernandez-Plaza C, et al. Evidence for clock genes circadian rhythms in human full-term placenta. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2015;61: 360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waddell BJ, Wharfe MD, Crew RC, Mark PJ. A rhythmic placenta? Circadian variation, clock genes and placental function. Placenta 2012;33: 533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Summa KC, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW. Environmental perturbation of the circadian clock disrupts pregnancy in the mouse. PLoS One 2012;7:e37668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.