Abstract

Background: Advance care planning (ACP) conversations are an important intervention to provide care consistent with patient goals near the end of life. The emergency department (ED) could serve as an important time and location for these conversations.

Objectives: To determine the feasibility of an ED-based, brief negotiated interview (BNI) to stimulate ACP conversations among seriously ill older adults.

Methods: We conducted a pre/postintervention study in the ED of an urban, tertiary care, academic medical center. From November 2017 to May 2019, we prospectively enrolled adults ≥65 years of age with serious illness. Trained clinicians conducted the intervention. We measured patients' ACP engagement at baseline and follow-up (3 ± 1 weeks) and reviewed electronic medical record documentation of ACP (e.g., medical order for life-sustaining treatment [MOLST]).

Results: We enrolled 51 patients (mean age = 71; SD 12), 41% were female, and 51% of patients had metastatic cancer. Median duration of the intervention was 11.8 minutes; few (6%) of the interventions were interrupted. We completed follow-up for 61% of participants. Patients' self-reported ACP engagement increased from 3.0 to 3.7 out of 5 after the intervention (p < 0.01). Electronic documentation of health care proxy forms increased (75%–94%, n = 48) as did MOLST (0%–19%, n = 48) during the six months after the ED visit.

Conclusion: A novel, ED-based, BNI intervention to stimulate ACP conversations for seriously ill older adults is feasible and may improve ACP engagement and documentation.

Keywords: advance care planning, behavioral intervention, brief negotiated interview, geriatrics, palliative care, serious illness

Introduction

Background

The absence of advance care planning (ACP) conversations among older adults with serious, life-limiting illness (expected mortality of less than 12 months) can be common and may result in avoidable suffering and lower quality of life.1–4 The percentage of patients with advanced cancer who report having ACP conversations, in which values and treatment preferences for serious illness and end-of-life care are discussed, varies significantly (18%–64%), with only 10% of patients on hemodialysis and 3%–11% of stage III and IV heart failure patients reporting ACP conversations.4–7 Most patients have multiple goals and priorities while living with serious illness, and without ACP conversations, many are at risk of receiving care discordant with their wishes.8 Patients with advanced cancer who did not report having ACP conversations were three times as likely to be admitted to the ICU, seven times as likely to receive mechanical ventilation, and eight times as likely to receive attempted resuscitation within their last week of life as those who reported having these conversations.3 ACP conversations are associated with lower probability of dying in the hospital, reduced stress, sustained reduction in anxiety and depression in surviving relatives, and higher likelihood of care provision that reflects patient goals and wishes.9–11 However, only 21% of older adults presenting to the emergency department (ED) have advance directives in place.12

Importance

Within the last six months of life, 75% of older adults with serious illness visit the ED.13 ED visits signal a rapid rate of decline in many patients' illness trajectories.14–16 Although ACP ideally would have occurred before a medical crisis, ED visits can be an opportune time for older adults to start formulating and communicating their goals for future care. ED clinicians recognize this opportunity.17 However, in the time-pressured ED environment, no feasible methods exist to engage seriously ill older adults in ACP.18–20 Therefore, to overcome the barriers and take advantage of this teachable opportunity in the ED, we propose a brief ED-based intervention to motivate seriously ill older adults to complete ACP conversations after leaving the ED.

Goals of this investigation

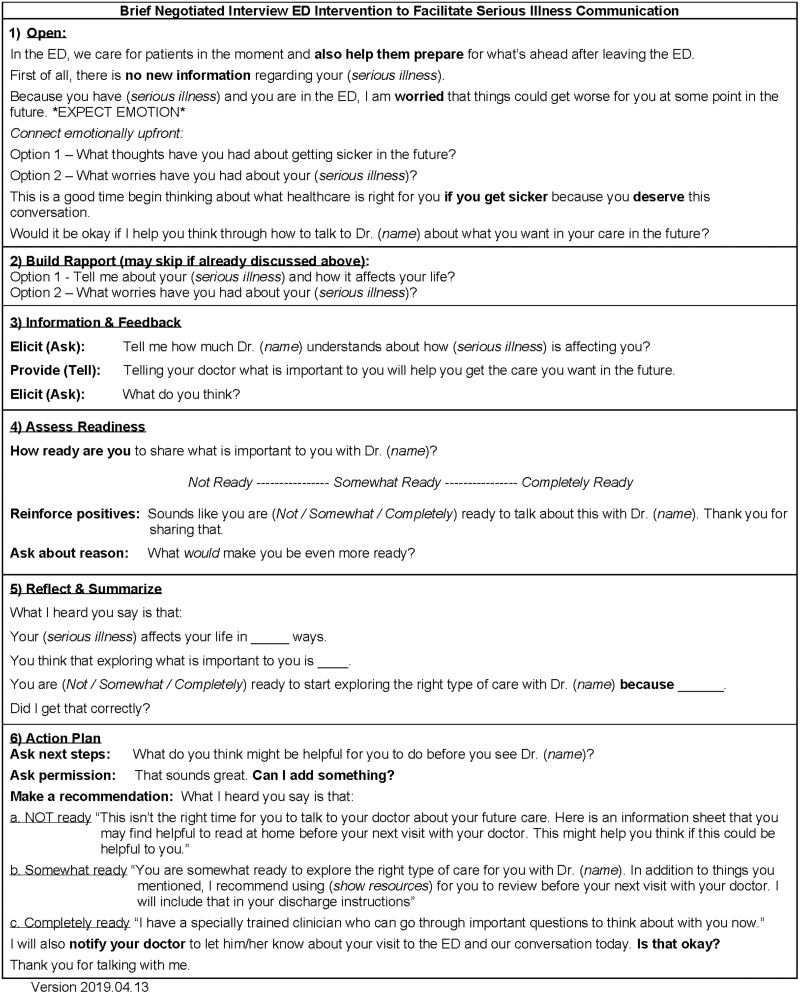

We developed, refined, and tested a brief negotiated interview (BNI) intervention to motivate seriously ill older adults to engage in ACP conversations with their primary outpatient clinicians (Fig. 1).21,22 BNI intervention is a short, scripted, motivational interview by a clinician that explores health behavior change with patients in a respectful, nonjudgmental way. Using clinicians' compassionate curiosity to show respect for patient autonomy, the BNI creates patient engagement and trust in targeted behavior change.23 BNI interventions are tailored to allow busy emergency clinicians to engage patients in addressing an important chronic care issue without conducting a time-consuming, sensitive conversation. In other studies, BNI interventions have demonstrated significant improvement in outcomes for ED patients with substance abuse disorders by helping patients understand the obstacles to and reasons for their medical care.24–27 In this study, we sought to determine the feasibility of conducting a BNI intervention during usual ED care to engage seriously ill older adults in ACP conversations after leaving the ED.

FIG. 1.

BNI script. BNI, Brief negotiated interview.

Methods

Study design

In this feasibility study, we conducted a prospective, one-arm, pre/postintervention study in the ED in an urban, tertiary care, academic medical center. All participants provided verbal informed consent. The study protocol was approved by Partners Human Research Committee. Registration information is available at clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03208530).

Participants

Participants were English-speaking adults 65 years and older with one or more serious illness (metastatic cancer, oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive lung disease, chronic kidney disease on dialysis, New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure). For patients who did not meet the above criteria but were identified as having life-limiting illness, a member of the research team asked each patient's treating ED clinician if they would “be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months” and included them in the study if the clinician stated that they “would not be surprised.”28 Only patients who were in individual patient rooms were considered for the study since the BNI intervention and outcome collection are technically difficult to conduct in hallways. Patients with clearly documented goals for medical care or with a medical order for life-sustaining treatment (MOLST) in the electronic medical record (EMR) were excluded. We also excluded patients determined to lack capacity or considered inappropriate by the treating clinicians (e.g., those in acute emotional or physical distress). During the first six months of the study, we recognized that hypoactive delirium or mild cognitive impairment may be prevalent among older adults in the ED and may not be detected during routine clinical encounters.29–31 These conditions may inhibit adequate execution of an ACP conversation and may also result in difficulty with follow-up. Therefore, for the last 12 months of the study, we added screening for hypoactive delirium (failed inattention item on the validated 3D-CAM32) or mild cognitive impairment (score of ≤2 out of 5 on the Mini-Cog© Cognitive Impairment Assessment33,34) not recognized by ED clinicians and excluded patients who met either of these criteria. This iterative and adaptive process was in line with the features of a feasibility study.35

Procedures

We used convenience sampling from 7 am to 6 pm, two to five days each month to recruit patients in the ED and ED observation unit from November 2017 to May 2019. Trained research assistants (RAs) identified potential participants using the EMR and confirmed initial eligibility with treating clinicians. After verbal consent was obtained from eligible patients, RAs collected responses to the ACP engagement survey as a baseline assessment. For the last 12 months of the study, RAs conducted additional screening and exclusion for cognitive impairment and hypoactive delirium before collection of this survey. A trained physician or physician assistant who was not a member of the patient's treatment team then administered the BNI. More in-depth description of the initial development and testing of the BNI intervention have been described previously.21,22

At the conclusion of the intervention, subjects received a sheet depicting helpful questions to discuss with their primary outpatient clinician. We videorecorded all encounters. Follow-up assessments were conducted through telephone or self-addressed envelope containing the questionnaires after three weeks (±1 week). Four open-ended questions were also asked about barriers to completing ACP conversations after leaving the ED. Participants were compensated with $15 and a certificate of participation.

Measures/outcomes

Feasibility outcomes

We used the standardized feasibility study framework previously described.35

Feasibility of recruitment and retention:

-

1.

Enrollment: >50% of eligible patients in the ED are willing to participate

-

2.

Retention: >50% of enrolled patients are able to complete the outcome assessment.

Feasibility of conducting the intervention

-

1.

Terminations of the intervention: >50% of enrolled patients complete the intervention once initiated in the ED (e.g., not terminated due to clinical decline, etc.).

-

2.

Interruption of the intervention: >50% of the interventions are interrupted less than twice before completion.

-

3.

Duration of the intervention: >50% of the interventions are conducted in less than 10 minutes.

Patient-centered outcomes

Our primary patient-centered outcomes were attitude and actions for ACP related to serious illness measured by a validated four-item ACP Engagement survey before and three weeks (±1 week) after our BNI intervention (Cronbach's α for English-speaking subjects = 0.86).36 The ACP Engagement survey was previously validated for similar studies to test patient responses to ACP interventions.36–38 The ACP engagement survey uses five-point Likert scale responses to measure patient readiness for ACP conversations (Table 1).37,39 We calculated descriptive and summary statistics for all participants. We used an average of the four-item responses for each subject to create a composite ACP score and performed item-by-item analysis of the ACP engagement survey to understand the components within the composite measure. Pre–post analysis was conducted using Wilcoxon's signed-rank tests to detect the change in the composite ACP engagement score as well as change for individual items. We considered a p-value of 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Table 1.

Pre/Postintervention Changes in Patient's Self-Reported Advance Care Planning Engagement and Electronic Medical Record Documentation

| ACP engagement survey, five total pointsa | Preintervention mean score (SD) | One-month postintervention mean score (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1: How ready are you to sign official papers naming a person or group of people to make medical decisions for you? (n = 28) | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.7) | 0.06 |

| Item 2: How ready are you to talk to your decision maker about the kind of medical care you would want if you were very sick or near the end of life? (n = 27) | 4.4 (1.1) | 4.6 (0.9) | 0.17 |

| Item 3: How ready are you to talk to your doctor about the kind of medical care you would want if you were very sick or near the end of life? (n = 28) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.3) | <0.01 |

| Item 4: How ready are you to sign official papers putting your wishes in writing about the kind of medical care you would want if you were very sick or near the end of life? (n = 24) | 3.3 (1.6) | 4.1 (1.3) | 0.06 |

| Composite (n = 24) | 3.8 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.9) | 0.02 |

| EMR documentation (n = 48, IRR = 98%) | Preintervention, no. of patients (%) | Six-month postintervention, no. of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health care proxy form |

36 (75%) |

47 (94%, 67% of whom were admitted to the hospital) |

|

| MOLST form | 0 (0%) | 9 (19%, all of whom were admitted to the hospital) |

Median intervention duration was 11.8 minutes (±4.4 minutes) with three interruptions during the entire study.

1. “I have never thought about it.”

2. “I have thought about it, but I am not ready to do it.”

3. “I am thinking about doing it in the next 6 months”/“I am thinking about doing it over the next few visits.”

4. “I am definitely planning to do it in the next 30 days”/“I am definitely planning to do it at the next visit.”

5. “I have already done it.”

ACP, advance care planning; EMR, electronic medical record; IRR, interrater reliability; MOLST, medical order for life-sustaining treatment; SD, standard deviation.

Our secondary patient-centered outcomes were: (1) qualitative follow-up responses to open-ended questions asking about reasons for presence or absence of ACP-related actions after leaving the ED at one month, and (2) ACP documentation in the EMR (new health care proxy and MOLST forms) within six months of the intervention. Qualitative responses were collected and recorded during a phone conversation. ACP documentation was collected by two RAs who were trained to complete chart abstraction using a refined abstraction codebook.40 To assess interrater reliability (IRR), 10% of the subjects' records (n = 5) were assessed by both reviewers. The reviewers resolved discrepancies by consensus (IRR = 98%).

Results

Feasibility assessment

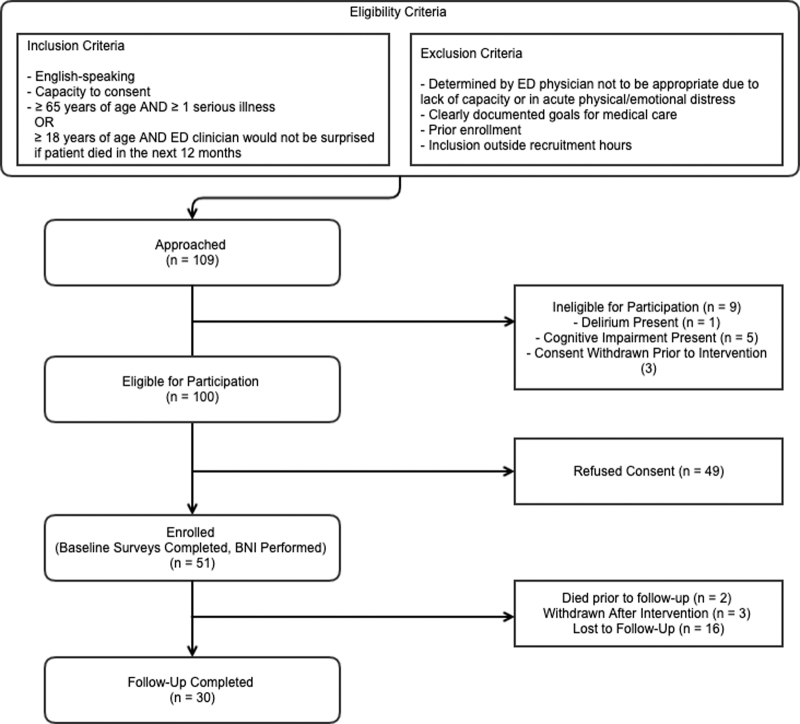

We approached 109 patients and 49 declined to participate. The most common refusal reasons were fatigue or feeling overwhelmed. The last 35 patients were screened for delirium and cognitive impairment. Nine patients were later found ineligible for participation. One failed the delirium screening, five failed the cognitive impairment assessments, and three were withdrawn for worsened clinical condition and/or changed their minds before the intervention. We enrolled 51 patients with mean age of 71 years (SD 12), 41% were female, and 51% of patients had metastatic cancer (Table 2). Clinicians spent a median of 11.8 minutes to complete the intervention, with 33% (17/51) in less than 10 minutes. Three interventions (6%) were interrupted, while no intervention was terminated completely. Among those who received the intervention, two died before the follow-up assessment, and three were withdrawn after the intervention because of increased burden of progressive serious illness after leaving the ED. Of the remaining 46 patients, 16 (35%) were lost to follow-up. During follow-up, 28 (61%) completed the ACP engagement survey and the open-ended questionnaires. The reasons for loss to follow-up included death (n = 2), patient refusal (e.g., “I am too tired from being hospitalized,” n = 3), and difficulty reaching them, despite having several forms of contact information and scheduled appointments (n = 16). Trained RAs performed chart abstraction to record changes in ACP documentation within six months of the intervention for the 48 patients who received the intervention and did not withdraw from the study. A detailed enrollment flowsheet can be found in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics

| Characteristics (N = 51) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 71.09 (12.6) |

| Sex | n (%) |

| Female | 21 (41) |

| Race | n (%) |

| White | 44 (86) |

| Black/African American | 5 (10) |

| Asian | 0 (0) |

| Other | 2 (4) |

| Ethnicity | n (%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (6) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 48 (94) |

| Life-limiting illness | n (%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 26 (51) |

| Oxygen-dependent COPD | 3 (5.9) |

| CKD on dialysis | 5 (9.8) |

| Stage 3 or 4 heart failure | 4 (7.8) |

| <12-Month mortality | 13 (25.5) |

| ED disposition (n = 48) | n (%) |

| Admitted to inpatient | 31 (65) |

| Admitted to observation | 7 (14) |

| Discharged | 10 (21) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department.

FIG. 2.

Study flow chart.

Primary patient-centered outcomes

The composite ACP engagement score increased from 3.8 to 4.3 out of 5 one month after the intervention (p = 0.02). In an item-by-item analysis (Item 3), self-reported readiness increased from 3.0 to 3.7 (p = 0.01, Table 1).

Secondary patient-centered outcomes

Three weeks following the intervention, 30 patients (59%) answered the open-ended questions (Table 3). The most common reason for deferral was fatigue from the burden of serious illness after leaving the ED. Responses to Question 1 identified several potential barriers to completion of ACP conversations. Eighteen patients (60%) answered that they had not spoken to their primary doctor. Common reasons included communication gaps among multiple outpatient clinicians (n = 7), primary focus on immediate health concerns like medication adjustment (n = 6), and lack of scheduled appointment before follow-up (n = 5). In response to Question 2, 25 patients (83%) answered “yes,” commonly stating that these ACP conversations were perceived positively, and the family knew and understood the patient's wishes. Question 3 demonstrated a potential area of improvement, with only 10 patients (34%) answering that they had reviewed the resource. Patients who reviewed the materials stated that they would like more specific questions. Among those who did not review the list, many stated that they did not remember receiving it or that it was misplaced after leaving the hospital. In response to Question 4, 22 (73%) answered “no.” These patients reported satisfaction with the intervention and stated that it was “good” or “easy.” Several patients stated that the process could be improved if their primary outpatient clinicians initiated the ACP conversations. One patient reported a negative response to the intervention and stated that the discussion was “too vague” and “not motivational.” Trained RAs both reviewed five (10%) of the total subjects' EMR to assess IRR for chart abstraction data. The EMR documentation of health care proxy form (75%–94%) and MOLST form (0%–19%) increased during the six months after the intervention (during the index or subsequent visits), mostly in patients who were admitted (IRR 98%, Table 1).

Table 3.

Qualitative Questions

| No. | Prompt |

|---|---|

| 1 | After leaving the ED, have you talked to your primary doctor about what care you would like in the future? |

| (Yes) Would you mind telling us a little bit about that conversation? | |

| (No) We are trying to better understand some of the reasons around why people don't speak to their primary doctor about these issues. Would you mind telling us through some of the reasons that influenced you around not having this discussion? | |

| 2 | After leaving the ED, have you talked to your family/loved ones about what care you would like in the future? |

| (Yes) From your perspective, how did that conversation go? | |

| (No) We are trying to better understand some of the reasons around why people don't speak to their family or loved ones about their future care. From your perspective, what types of things come to mind when you think about not wanting to have this discussion? | |

| 3 | One of the resources that we gave you was a list of questions about your care, have you gone through that list since you left the ED? |

| (Yes) Can you tell me a bit more about when/why you looked over the paper? | |

| (No) Was there anything that could be improved about the list of question that would make it more useful to you? | |

| 4 | Is there anything we can do to make discussions about your care in the future easier? |

| (Yes) Please specify | |

| (No) Is there anything else we should consider as we try to encourage other people to discuss their care in the future? |

Discussion

Among the seriously ill older adults who were approached and met our eligibility criteria in the ED, 51 patients (51%) completed our intervention (median intervention time 11.8 minutes), and 61% of them completed the follow-up survey after one month. Patient's self-reported ACP engagement increased from 3.0 to 3.7 out of 5 after the intervention (p < 0.01, Item 3, Table 1). Patients were more ready to have ACP conversations with family members (83%) than their primary care physicians (40%) during the first month after the intervention. The EMR documentation of health care proxy form (75%–94%) and MOLST form (0%–19%) increased during the six months after the intervention, mostly in patients who were admitted (IRR 98%, Table 1). A brief intervention to engage seriously ill older adults to complete ACP conversation is feasible and may increase patient's ACP engagement after leaving the ED.

This is the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of using BNI to motivate engagement in ACP conversations among seriously ill older adults during their ED visits.22 Although similar studies have attempted to utilize the motivational interview structure in palliative and end-of-life settings, our study is the first to use the ED.41–45 While outpatient settings may be more appropriate for completion of ACP conversations, the ED serves as an important inflection point of illness trajectory for many seriously ill older adults. Our BNI intervention may serve as an important step to facilitate completion of ACP conversations in these other settings.16 In the future, we will consider adding hand-off documentation to inpatient teams after our intervention to facilitate further communication and ACP documentation.

This is also the first study to use the ACP engagement survey to detect the impact of an ACP intervention in the ED. The ACP engagement survey includes responses centered around the stages described by the transtheoretical model of behavior change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance) to measure patients' engagement with and movement between stages of ACP.46 This model has previously been described as an important framework for ACP conversations and allows for the recognition of potential patient-perceived barriers to ACP and their subsequent address.47–49 Our findings suggest that our intervention may guide patients toward the next stage in the ACP behavior change process.

We also learned that close attention to cognitive impairment assessment, compensation for participants at the time of outcome assessment, and use of multiple modalities to complete the follow-up are critical to improving the recruitment and retention of this population in the ED. Given that patients did not recall the paper resource we provided to them, in the future we should consider alternative methods to provide this information. The physical and emotional burden of an ED visit/hospitalization may necessitate alternative methods (i.e., postal mail, email) for delivery of this resource.50

Participant compensation and multiple modalities for follow-ups are necessary to motivate participants to complete the required follow-ups at their convenience.51,52 Further refinement of the intervention is necessary to improve its potential efficacy and scalability. The intervention in this study averaged 11.8 minutes to complete, with 17 (33%) interactions completed in less than 10 minutes. While this might be ideal in nonemergency settings, the mean time to interruption for emergency physicians is 6.4 minutes.53 Therefore, this specific feasibility criterion (duration of the intervention: >50% of the intervention are conducted in less than 10 minutes) was the sole criterion not met in this study.

Our intervention is at the stage IB preliminary testing stage of the Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development,54 which necessitates “best possible setting” to test its potential efficacy. To improve the potential efficacy and scalability for future Phase III and IV studies, further intervention refinement is needed to shorten the intervention duration, include patients with cognitive impairment and their caregivers, and consider alternative models to deliver the intervention (e.g., mimic the specialized board certification process of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners [SANE] to provide higher quality of care55–57). ACP CPT codes 99497 and 99498, established in 2016 by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, reimburse for ACP conversations. The reimbursement amounts range from $75 to $106 (1.40–1.50 RVUs) and may help to ensure sustainability of this intervention.58,59 Furthermore, the population-level impact of providing earlier, better, and more frequent ACP conversations will likely lead to not only delivering goal-concordant care, but also may result in an overall reduction in health care expenditure.8–11,60,61

Limitations

This was a single-site study, utilizing a small sample of patients, and patient population may affect the feasibility. Using specifically trained clinicians to administer the intervention outside of their normal clinical duties may require implementation considerations in the future. Future testing will address these implementation challenges. Given that our intervention is in stage 1B (preliminary testing stage) of the Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development, where any signal toward the desired outcome is valuable, implementation/dissemination concerns are outside the scope of this study.54 Enrollments during the first six months (n = 25) of the study did not include a process for screening and excluding patients with cognitive impairment or delirium. Inclusion of patients with mild cognitive impairment or hypoactive delirium undetected by ED clinicians could have negatively impacted our follow-up rates and biased our results toward null. As a feasibility study intended to demonstrate the feasibility of administering and studying our intervention for future studies, the necessity of cognitive impairment and delirium screening was a worthwhile discovery. Once this work has been completed, we plan to develop strategies in the future to include patients with cognitive impairment and their caregivers.

Conclusion

A brief ACP intervention is feasible to engage seriously ill older adults to complete ACP conversations after leaving the ED, however, efficiency and timing must be addressed in future studies. Our results indicate that patients are willing to participate in this intervention and that the intervention has the potential to increase self-reported ACP engagement, which may be a precursor to ACP execution. Examination of the efficacy of this intervention requires further study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Lauren A. Fellion, PA-C and Ms. Audrey C. Reust, PA-C for administering our intervention with high intervention fidelity and Mr. Askar Myrzakhmetov for assisting with chart abstraction.

Authors' Contributions

S.E.P., M.A.H., N.G., R.S., M.A.S., E.B., J.A.T., S.D.B., and K.O. conceived the article concept. K.O., A.C.R., and L.A.F., conducted the intervention and all authors contributed substantially to intervention administration, study refinement, outcome collections, and analysis. S.E.P., M.A.H., and K.O. drafted the article, and all authors contributed substantially to the article revisions.

Funding Information

Dr. Ouchi is supported by the Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists' Transition to Aging Research award from the National Institute on Aging (R03 AG056449), the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Bernacki RE, Block SD: Communication about serious illness care goals. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. : End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. : Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heyland DK, Allan DE, Rocker G, et al. : Discussing prognosis with patients and their families near the end of life: Impact on satisfaction with end-of-life care. Open Med 2009;3:e101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. : Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: A cluster randomized clinical trial of the Serious Illness Care Program. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD: Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:854–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barclay S, Momen N, Case-Upton S, et al. : End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e49–e62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. : Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476–2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM: Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1211–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Degenholtz HB, Rhee Y, Arnold RM: Brief communication: The relationship between having a living will and dying in place. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W: The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oulton J, Rhodes SM, Howe C, et al. : Advance directives for older adults in the emergency department: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 2015;18:500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. : Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1277–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW, Allen KR: Short-term functional decline and service use in older emergency department patients with blunt injuries. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:679–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Sabbe M, et al. : Characteristics of older adults admitted to the emergency department (ED) and their risk factors for ED readmission based on comprehensive geriatric assessment: A prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagurney JM, Fleischman W, Han L, et al. : Emergency department visits without hospitalization are associated with functional decline in older persons. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:426–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stone SC, Mohanty S, Grudzen CR, et al. : Emergency medicine physicians' perspectives of providing palliative care in an emergency department. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1333–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA, et al. : Am I doing the right thing? Provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:86–93, 93 e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dy SM, Herr K, Bernacki RE, et al. : Methodological research priorities in palliative care and hospice quality measurement. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E: Identifying the population with serious illness: The “Denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med 2018;21(S2):S7–S16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leiter RE, Yusufov M, Hasdianda MA, et al. : Fidelity and feasibility of a brief emergency department intervention to empower adults with serious illness to initiate advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:878–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ouchi K, George N, Revette AC, et al. : Empower seriously ill older adults to formulate their goals for medical care in the emergency department. J Palliat Med 2019;22:267–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Feldman J, et al. : An evidence based alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) curriculum for emergency department (ED) providers improves skills and utilization. Subst Abus 2007;28:79–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. D'Onofrio G, Degutis LC: Screening and brief intervention in the emergency department. Alcohol Res Health 2004;28:63–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. D'Onofrio G, Degutis LC: Integrating Project ASSERT: A screening, intervention, and referral to treatment program for unhealthy alcohol and drug use into an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:903–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. D'Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, et al. : Development and implementation of an emergency practitioner-performed brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:249–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. : Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;313:1636–1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ouchi K, Jambaulikar G, George NR, et al. : The “surprise question” asked of emergency physicians may predict 12-month mortality among older emergency department patients. J Palliat Med 2018;21:236–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elie M, Rousseau F, Cole M, et al. : Prevalence and detection of delirium in elderly emergency department patients. CMAJ 2000;163:977–981 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hustey FM, Meldon SW: The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. : Delirium in older emergency department patients: Recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:193–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O'Connor M, et al. : 3D-CAM: Derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: A cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:554–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilber ST, Lofgren SD, Mager TG, et al. : An evaluation of two screening tools for cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:612–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, et al. : Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: Comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini-Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:871–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Orsmond GI, Cohn ES: The distinctive features of a feasibility study: Objectives and guiding questions. OTJR (Thorofare N J) 2015;35:169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, et al. : Measuring advance care planning: Optimizing the Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:669–681 e668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sudore RL, Boscardin J, Feuz MA, et al. : Effect of the PREPARE Website vs an Easy-to-read advance directive on advance care planning documentation and engagement among veterans: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1102–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, et al. : Outcomes that define successful advance care planning: A Delphi Panel Consensus. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:245–255 e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sudore RL, Stewart AL, Knight SJ, et al. : Development and validation of a questionnaire to detect behavior change in multiple advance care planning behaviors. PLoS One 2013;8:e72465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, et al. : Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med 1996;27:305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ko E, Hohman M, Lee J, et al. : Feasibility and acceptability of a brief motivational stage-tailored intervention to advance care planning: A Pilot Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:834–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Gonzalez K, et al. : Implementing an advance care planning intervention in community settings with older Latinos: A feasibility study. J Palliat Med 2017;20:984–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pollak KI, Childers JW, Arnold RM: Applying motivational interviewing techniques to palliative care communication. J Palliat Med 2011;14:587–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomas ML, Elliott JE, Rao SM, et al. : A randomized, clinical trial of education or motivational-interviewing-based coaching compared to usual care to improve cancer pain management. Oncol Nurs Forum 2012;39:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fried TR, Leung SL, Blakley LA, Martino S: Development and pilot testing of a motivational interview for engagement in advance care planning. J Palliat Med 2018;21:897–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. : A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: Start with patients' self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:31–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. : Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: A descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1006–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levoy K, Salani DA, Buck H: A systematic review and gap analysis of advance care planning intervention components and outcomes among cancer patients using the transtheoretical model of health behavior change. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:118–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB: Older adults in the emergency department: A systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Eemerg Med 2002;39:238–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bernstein SL, Feldman J: Incentives to participate in clinical trials: Practical and ethical considerations. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1197–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Keating NL, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein J, et al. : Randomized trial of $20 versus $50 incentives to increase physician survey response rates. Med Care 2008;46:878–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chisholm CD, Dornfeld AM, Nelson DR, Cordell WH: Work interrupted: A comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, et al. : Reenvisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci 2014;2:22–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Campbell R, Patterson D, Lichty LF: The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs: A review of psychological, medical, legal, and community outcomes. Trauma Violence Abuse 2005;6:313–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sievers V, Murphy S, Miller JJ: Sexual assault evidence collection more accurate when completed by sexual assault nurse examiners: Colorado's experience. J Emerg Nurs 2003;29:511–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Campbell R, Townsend SM, Long SM, et al. : Responding to sexual assault victims' medical and emotional needs: A national study of the services provided by SANE programs. Res Nurs Health 2006;29:384–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. CMS. Advance Care Planning Printer Friendly Version. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/AdvanceCarePlanning.pdf. 2019. (Last accessed April10, 2020)

- 59. CMS. License for Use of Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition (“CPT®”). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/license-agreement.aspx 2019. (Last accessed April12, 2020)

- 60. Starr LT, Ulrich CM, Corey KL, Meghani SH: Associations among end-of-life discussions, health-care utilization, and costs in persons with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2019;36:913–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Klingler C, in der Schmitten J, Marckmann G: Does facilitated advance care planning reduce the costs of care near the end of life? Systematic review and ethical considerations. Palliat Med 2016;30:423–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]