Abstract

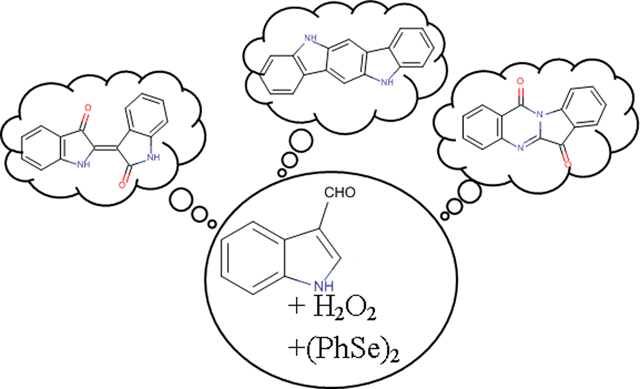

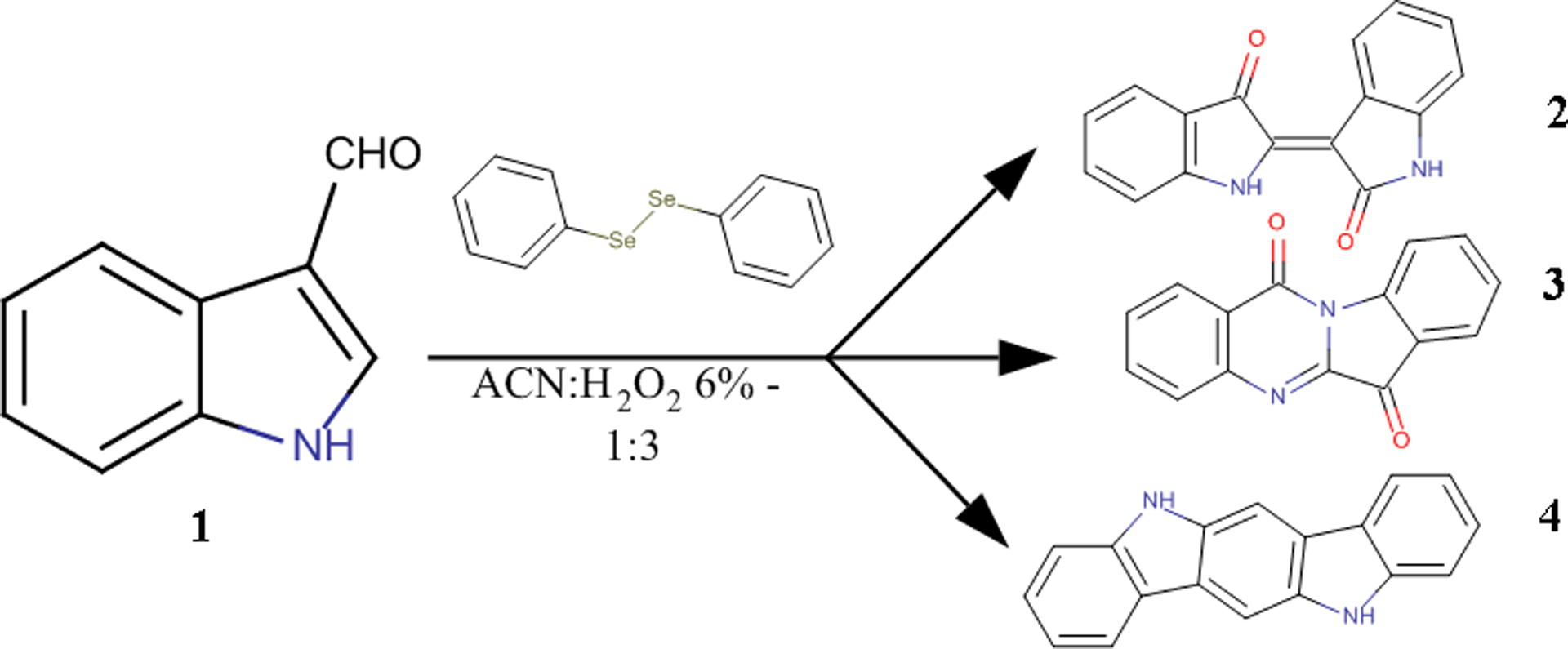

Malassezia furfur isolates from diseased skin preferentially biosynthesize compounds which are among the most active known Aryl-hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) inducers, such as indirubin, tryptanthrin, indolo[3,2-b]carbazole and 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole. In our effort to study their production from Malassezia spp., we investigated the role of indole-3-carbaldehyde (I3A), the most abundant metabolite of Malassezia when grown on tryptophan agar, as a possible starting material for the biosynthesis of the alkaloids. Treatment of I3A with H2O2 and use of catalysts like diphenyldiselenide resulted in the simultaneous one-step transformation of I3A to indirubin and tryptanthrin in good yields. The same reaction was first applied on simple indole and then on substituted indoles and indole-3-carbaldehydes, leading to a series of mono- and bi-substituted indirubins and tryptanthrins bearing halogens, alkyl or carbomethoxy groups. Afterwards, they were evaluated for their AhR agonist activity in recombinant human and mouse hepatoma cell lines containing a stably transfected AhR-response luciferase reporter gene. Among them, 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin was found to be equipotent to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) as an AhR agonist and 3-bromotryptanthrin was 10-times more potent than TCDD in the human HG2L7.5c1 cell line. In contrast, 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin and 3-bromotryptanthrin were ~4,000- and >10,000-times less potent than TCDD in the mouse H1L7.5c3 cell line, respectively, demonstrating that they are species-specific AhR agonists. Involvement of the AhR in the action of 3-bromotryptanthrin was confirmed by the ability of the AhR antagonists CH223191 and SR1 to inhibit 3-bromotryptanthrin-dependent reporter gene induction in human HG2L7.5c1 cells. In conclusion, I3A can be the starting material used by Malassezia for the production of both indirubin and tryptanthrin through an oxidation mechanism and modification of these compounds can produce some highly potent, efficacious and species-selective AhR agonists.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Malassezia yeasts are part of the human skin microbiota that can become pathogenic and cause serious infections such as seborrhoeic dermatitis, pytiriasis versicolor, dandruff and psoriasis.1 Extensive studies have revealed the preferential biosynthesis of indole derivatives by Malassezia furfur isolates from lessional skin which are among the most potent Aryl-hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) activators known, e.g. indirubin, tryptanthrin, indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (ICZ) and 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (6-FICZ).2–4 Although the production of the above AhR activators seems to be a general characteristic of the genus, specific Malasezia species and strains are able to overproduce them and consequently their constant presence in the skin at elevated concentrations has been proposed to be implicated in the development of skin diseases.2,3 However up today there is no available data about the biosynthetic origin of those compounds except that they are related with tryptophan.

Having as ultimate target of future works the inhibition of their overproduction and possibly the inhibition of their toxic effects for skin, we considered as a very important first step to investigate the role of potential biosynthetic precursors and the chemical mechanism that could lead to their production, mimicking what is potentially happening with Malassezia.The first compound that was investigated as a possible starting material for the biosynthesis of the alkaloids was indolo-3-carbaldehyde, I3A (1), the most abundant metabolite of all studied Malassezia strains when cultured with L-tryptophan as single nitrogen source.5, 6

During early trials, the treatment of I3A (1) with H2O2 and acetic acid resulted in intensively colored solutions, suggesting thus the formation of indigoids. The major product was indigo but other indole derivatives such as indirubin (2) could be detected in traces by NMR spectroscopy. Further trials under Baeyer-Villiger oxidation conditions led to increased yield of indirubin (2). This type of reaction is commonly used for the transformation of aromatic ketones and aldehydes to the corresponding esters7 but in this case it led to more complicated structures. For realizing this reaction we chose, among the available oxidants, hydrogen peroxide due to its eco-friendly nature, its natural presence and that exposure to H2O2 occurs in most human cells.8 We also investigated the use of a potential catalyst in order to promote the reaction and enhance the yield of the desirable compounds. A thorough investigation of several parameters led to the discovery of a biomimetic reaction that can possibly explain the common presence of indirubin (2) and tryptanthrin (3) in Malassezia extracts. Complementary to this assumption is a recent publication that indicates the synthesis, from indole-3-acetaldehyde upon treatment with H2O2, of 6-FICZ, another Malassezia metabolite.9 Although we were unable to detect indole-3-acetaldehyde in the extracts of Malassezia species, it is biosynthetically a probable product of tryptophan metabolism.10

At a next step, the above described reaction was applied to several substituted indolic monomers for the preparation of a series of new or known indirubin and tryptanthrin derivatives, having as target the investigation of the structure-activity relationships concerning the AhR activation. Finally, all the synthesized analogues were evaluated for their stimulate AhR-dependent gene expression, leading to the identification of some compounds with significantly increased potency and efficacy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Equipment

All the solvents used during the experimental procedure were of analytical grade or distilled. Aluminum and glass plates, covered with silicon dioxide (Silica gel 60 F254) were used for TLC and preparative TLC respectively and the obtained chromatograms were observed in a CAMAG TLC Visualizer at 254 and 366 nm. All the one- and two-dimensional NMR spectra of the purified compounds, as well as the calculations of the reaction yields, were acquired in a Bruker UltrashieldTM Plus 600MHz NMR.

Initial methodology of the reaction on I3A (1)

0.34 mmol of I3A (1) were dissolved in 1.0 mL distilled DCM while 0.1 mL H2O2 10% and 0.05 mmol of (PhSe)2 were then added in the reaction mixture. The flask was covered with aluminum foil to prevent occurrence of any light-induced side-reactions and the solution was stirred for 1.5 hours at room temperature (rt). Then, the same quantities of catalyst and oxidative reagent were added again and the reaction remained under mechanical stirring overnight at rt. After the formation of a dark-colored solution, MeOH was added in the mixture and it was evaporated to dryness. Then the crude mixture was submitted to column chromatography for the isolation of the produced compounds.

Modification of the reaction and application on I3A (1) and indole (8)

The modified protocol for the investigation of the above reaction was based on a method described by Santoro et al.11 0.4 mmol of I3A (1) or indole (8) were added to a mixture of 2.1 mL H2O2 6% and 0.7 mL acetonitrile containing a catalytic amount of (PhSe)2 (0.04 mmol). The reaction remained under mechanical stirring for 72h at 23°C. The precipitate was filtered, washed with water, then solubilized with THF, collected and evaporated to dryness. The isolation of the synthesized compounds 2 and 3 was performed with preparative TLC and their structure elucidation with NMR spectroscopy.

Optimization of the reaction conditions

For the optimization of the reaction, numerous trials were performed by modifying and investigating parameters such as the oxidative means, the catalyst or the quantity of the reagents. These efforts were carried out in parallel, under the same environmental conditions and by modifying only one parameter at the time. In all cases the starting material was I3A (1) and the mixture was stirred for 72h at 23°C. All the attempts are summarized in Table 1, leading to some interesting remarks and conclusions for this synthesis.

Table 1:

Trials of the biomimetic reaction with modification of the reagents’ quantities

| Entry | Oxidative Means | Catalyst | Quantity of catalyst | Solvent | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H2O2 6% | (PhSe)2 | 10% | ACN | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

| 2 | H2O2 6% | (PhSe)2 | 10% | - | Hyperoxidation |

| 3 | H2O2 6% | - | - | ACN | n.d. |

| 4 | H2O2 6% | (PhSe)2 | 20% | ACN | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

| 5 | H2O2 6% | (PhSe)2 | 50% | ACN | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

| 6 | H2O212% | (PhSe)2 | 10% | ACN | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

| 7 | H2O212% | (PhSe)2 | 10% | - | Hyperoxidation |

| 8 | H2O212% | - | - | ACN | n.d. |

| 9 | H2O212% | (PhSe)2 | 20% | ACN | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

| 10 | H2O212% | (PhSe)2 | 50% | ACN | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

n.d.: not detected

For further examination of the optimal conditions, the environmental conditions were then modified, namely the temperature and the reaction time. The starting material was once again I3A (1) and the reagents the same as the ones referred to entry 1 of Table 1. These experiments are listed in Table 2.

Table 2:

Trials of the biomimetic reaction with modification of the conditions

| Entry | Temperature | Reaction Time | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0–23°C | 72h | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

| 12 | ~10°C | 72h | Lower yield |

| 13 | 40°C | 72h | Lower yield |

| 14 | 23°C | 120h | Indirubin&Tryptanthrin |

Investigation of the reaction mechanism

To explore the mechanism of the reaction and its’ potentials, we then applied the reaction on compounds that bear longer chains in the position 3 of the indolic scaffold (e.g. tryptophan and tryptamine). Moreover, aiming to examine the necessity and the nature of the nitrogen atom in position 1 of the aromatic core, we used benzo[b]thiophene and N-Boc-indolo-3-carbaldehyde as staring materials. In all cases the aforementioned developed protocol was applied.

General protocol for the synthesis of compounds 2–2h and 3–3h

A quantity (0.4 mmol) of the appropriately substituted indolic compound was added to a mixture of 2.1 mL H2O2 6% and 0.7 mL acetonitrile containing a catalytic amount of (PhSe)2 (0.04 mmol). The reaction remained under mechanical stirring for 72h at 23°C. The produced precipitate was filtered, washed with water, then solubilized with THF, collected and evaporated to dryness.

The isolation of the synthesized compounds was performed with preparative TLC and their structure elucidation with NMR Spectroscopy. The synthesized compounds and the reaction yields are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

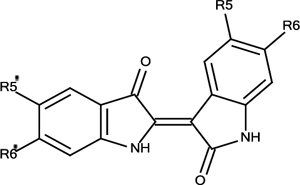

Table 3:

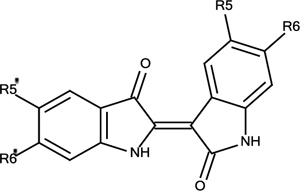

Synthetic Analogues of Indirubin (2)

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Substitution | Yield | |

| 2 | R5=R6=R5’=R6’=H | 5% |

| 2a | R5=R5’=F, R6=R6’=H | 5% |

| 2b | R5=R5’=Cl, R6=R6’=H | 5% |

| 2c | R5=R5’=Br, R6=R6’=H | 6% |

| 2d | R5=R5’=CH3, R6=R6’=H | 6% |

| 2e | R5=R5’=COOCH3, R6=R6’=H | 17% |

| 2f | R5=R5’=H, R6=R6’=Br | 5% |

| 2g | R5=R5’=H, R6=R6’=COOCH3 | 14% |

| 2h | R5=R5’= R6=H, R6’=Br | 5% |

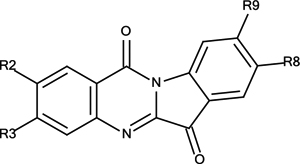

Table 4:

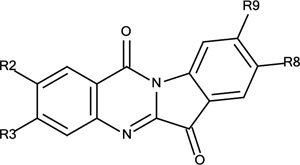

Synthetic Analogues of Tryptanthrin (3)

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Substitution | Yield | |

| 3 | R2=R3=R8=R9=H | 12% |

| 3a | R2=R8=F, R3=R9=H | 16% |

| 3b | R2=R8=Cl, R3=R9=H | 10% |

| 3c | R2=R8=Br, R3=R9=H | 12% |

| 3d | R2=R8=CH3, R3=R9=H | 15% |

| 3e | R2=R8=COOCH3, R3=R9=H | 27% |

| 3f | R2=R8=H, R3=R9=Br | 13% |

| 3g | R2=R8=H, R3=R9=COOCH3 | 18% |

| 3h | R2=R8= R9=H, R3=Br | 12% |

Synthesis of indirubin (2) and tryptanthrin (3):

The general method was followed using as starting material either I3A (1) or indole (8). In both cases the produced alkaloids and their yields were equivalent.

Indirubin (2)

Purple solid; Yield: 5%; Rf=0.50 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 1:1 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Adachi et al.12 and are given in Supporting Information.

Tryptanthrin (3)

Yellow solid; Yield: 12%; Rf=0.63 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 1:1 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Jao et al.13 and are given in Supporting Information.

Synthesis of 5,5’-difluoroindirubin (2a) and 2,8-difluorotryptanthrin (3a):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 5-fluoroindole.

5,5’-difluoroindirubin (2a)

Purple solid; Yield: 5%; Rf=0.18 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid. Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.14 and are given in Supporting Information.

2,8-difluorotryptanthrin (3a)

Yellow solid; Yield: 16%; Rf=0.53 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.15 and are given in Supporting Information.

Synthesis of 5,5’-dichloroindirubin (2b) and 2,8-dichlorotryptanthrin (3b):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 5-chloroindole.

5,5’-dichloroindirubin (2b)

Purple solid; Yield: 5%; Rf=0.21 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Riepl et Urmann16 and are given in Supporting Information.

2,8-dichlorotryptanthrin (3b)

Yellow solid; Yield: 10%; Rf=0.63 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.15 and are given in Supporting Information.

Synthesis of 5,5’-dibromoindirubin (2c) and 2,8-dibromotryptanthrin (3c):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 5-bromoindole.

5,5’-dibromoindirubin (2c)

Purple solid; Yield: 6%; Rf=0.44 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Beauchard et al.17 and are given in Supporting Information.

2,8-dibromotryptanthrin (3c)

Yellow solid; Yield: 12%; Rf=0.64 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.15 and are given in Supporting Information.

Synthesis of 5,5’-dimethylindirubin (2d) and 2,8-dimethylotryptanthrin (3d):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 5-methylindole.

5,5’-dimethylindirubin (2d)

Purple solid; Yield: 6%; Rf=0.23 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.14 and are given in Supporting Information.

2,8-dimethylotryptanthrin (3d)

Yellow solid; Yield: 15%; Rf=0.46 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.15 and are given in Supporting Information.

Synthesis of 5,5’-dicarbomethylindirubin (2e) and 2,8-dicarboxymethylotryptanthrin (3e):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 5-carboxymethylindole.

5,5’-dicarboxymethylindirubin (2e)

Red solid; Yield: 17%; Rf=0.27 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 1:1 + 1.5% acetic acid). 1H-NMR ((CD3)2SO, 600MHz): δ 11.44 (brs, -NH); 11.34 (brs, -NH); 9.45 (d, H-4, J=1.7Hz); 8.18 (brs, H-4’); 8.16 (dd, H-6’, J=8.5Hz, 1.6Hz); 7.93 (dd, H-6, J=8.2Hz, 1.7Hz); 7.54 (d, H-7’, J=8.5Hz); 7.02 (d, H-7, J=8.2Hz); 3.88 (s, 3H, -CH3); 3.86 (s, 3H, -CH3).

2,8-dicarboxymethylotryptanthrin (3e)

Yellow solid; Yield: 27%; Rf=0.52 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 1:1 + 1.5% acetic acid). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600MHz): δ 9.11 (d, H-1, J=1.8Hz); 8.73 (d, H-10, J=8.4Hz); 8.59 (d, H-7, J=1.4Hz); 8.51 (dd, H-3, J=8.4Hz, 1.8Hz); 8.49 (dd, H-9, J=8.4Hz, 1.4Hz); 8.10 (d, H-4, J=8.4Hz); 4.02 (s, 3H, -CH3); 3.99 (s, 3H, -CH3)

Synthesis of 6,6’-dibromoindirubin (2f) and 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin (3f):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 6-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde.

6,6’-dibromoindirubin (2f)

Red solid; Yield: 5%; Rf=0.28 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Clark et Cooksey18 and are given in Supporting Information.

3,9-dibromotryptanthrin (3f)

Yellow solid; Yield: 13%; Rf=0.65 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3 + 1.5% acetic acid). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600MHz): δ 8.84 (d, H-10, J=1.6Hz); 8.28 (d, H-1, J=8.5Hz); 8.19 (d, H-4, J=1.8Hz); 7.80 (dd, H-2, J=8.5Hz, 1.8Hz); 7.70 (d, H-7, J=8.1Hz); 7.61 (dd, H-8, J=8.1Hz, 1.6Hz)

Synthesis of 6,6’-dicarbomethylindirubin (2g) and 3,9-dicarboxymethylotryptanthrin (3g):

The general method was followed using as starting material the 6-carboxymethylindole.

6,6’-dicarboxymethylindirubin (2g)

Purple solid; Yield: 14%; Rf=0.40 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 1:1 + 1.5% acetic acid). 1H-NMR ((CD3)2SO, 600MHz): δ 11.45 (brs, -NH); 11.08 (brs, -NH); 8.82 (d, H-4, J=8.2Hz); 8.06 (brs, H-7’); 7.79 (d, H-4’, J=8.0Hz); 7.67 (d, H-5’, J=8.0Hz); 7.60 (d, H-5, J=8.2Hz); 7.43 (brs, H-7); 3.90 (s, 3H, -CH3); 3.86 (s, 3H, -CH3)

3,9-dicarboxymethylotryptanthrin (3g)

Yellow solid; Yield: 17%; Rf=0.59 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 1:1 + 1.5% acetic acid). Spectral data are in accordance to Wang et al.15 and are given in Supporting Information.

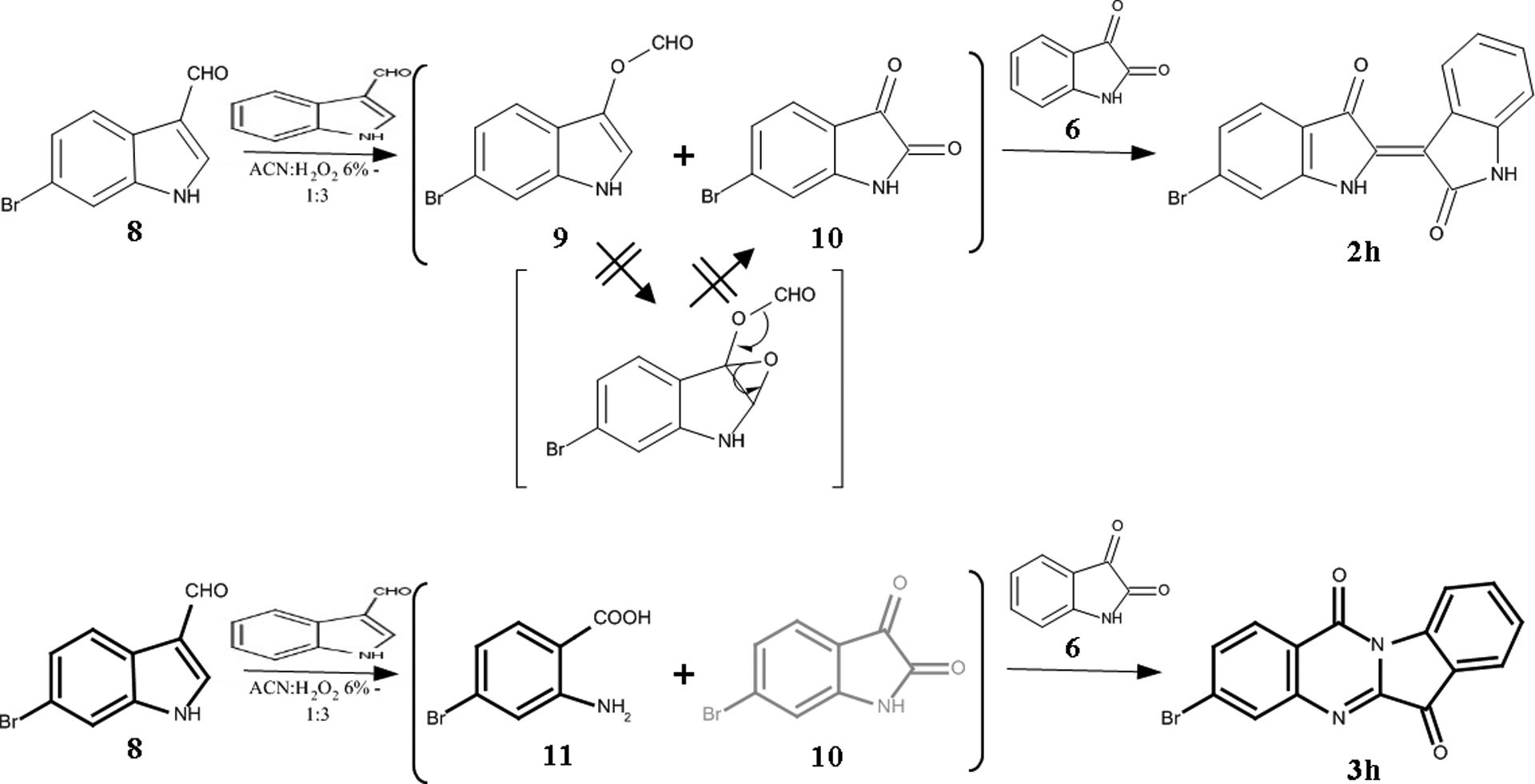

Synthesis of 6’-bromoindirubin (2h) and 3-bromotryptanthrin (3h):

The general method was followed using as starting material equivalent quantities of I3A (1) and 6-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (8). The quantities of all the reagents were doubled.

6’-bromoindirubin (2h)

Purple solid; Yield: 5%; Rf=0.38 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3). Spectral data are in accordance to Clark et Cooksey18 and are given in Supporting Information.

3-bromotryptanthrin (3h)

Yellow solid; Yield: 12%; Rf=0.53 (cyclohexane:EtOAc – 7:3). Spectral data are in accordance to Li et al.19 and are given in Supporting Information.

Calculation of the reaction yields with NMR Spectroscopy

The calculation of the reaction yields was performed using quantitative 1H-NMR spectroscopy in a similar way as previously described for metabolite quantitation in complex natural mixtures.20 The spectra were acquired in solution of the reaction mixtures after the work up described above at specific concentration in (CD3)2SO, where a known quantity of syringaldehyde was added as Internal Standard. Using the peak of the aldehyde group of syringaldehyde at 9.79 ppm for comparison, the ratio of the reactants/products was measured in the reaction mixture.

Protocol for the evaluation of AhR activity

The synthesized alkaloids were evaluated for their ability to activate AhR-dependent gene expression in two different recombinant cell lines (human hepatoma (HG2L7.5c1) and mouse hepatoma (H1L7.5c3),) containing the identical stably transfected AhR-responsive luciferase reporter gene plasmid, pGudLuc7.5.21, 22 The results (EC50 (M)) calculated from concentration-response experiments were compared to those of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), the prototypical and highly potent AhR agonist. The AhR activity protocol was derived from He et al.23 and was as follows:

Human and mouse cell lines were grown in 100-mm tissue culture plates (Corning Glass Works; Corning, NY) using sterile techniques, maintained in culture medium (alpha-minimum essential media (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and G418 (1 mg/mL)) and incubated at >80% humidity and 37°C.

For AhR-dependent gene expression analysis, plates of human or mouse cells (approximately 80–100% confluent) were trypsinized and resuspended in 20 mL culture media. An aliquot (100 μL) of the indicated cell suspension was added into sterile 96-well tissue culture plates (Corning) and plates were incubated for 24 h prior to chemical exposure, allowing cells to attach and reach confluence. Prior to ligand addition, wells were washed with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then cells were incubated with culture media containing DMSO (10 μL/mL) or the indicated concentration of TCDD or test compounds in DMSO for 6h or 24h at 37°C. For AhR antagonist studies, cells were incubated with TCDD or 3-bromotryptanthrin in the absence or presence of the indicated concentration of the AhR antagonist CH223191 (Chembridge Corporation; San Diego, CA) or StemRegenin1 (SR1) (Cayman Chemicals; Ann Arbor, MI)) for 6h at 37°C.

After incubation cells were washed twice with PBS, 100 μL of 1X Lysis buffer (Promega; Madison, WI) was added to each well and the plate shaken at room temperature until cells were lysed (approximately 20 min). Luciferase activity was measured using an automated microplate luminometer (Anthos Lucy2, Austria) in enhanced flash mode with the automatic injection of 50 μL of Promega stabilized luciferase reagent.

RESULTS

Initial methodology of the reaction on I3A (1)

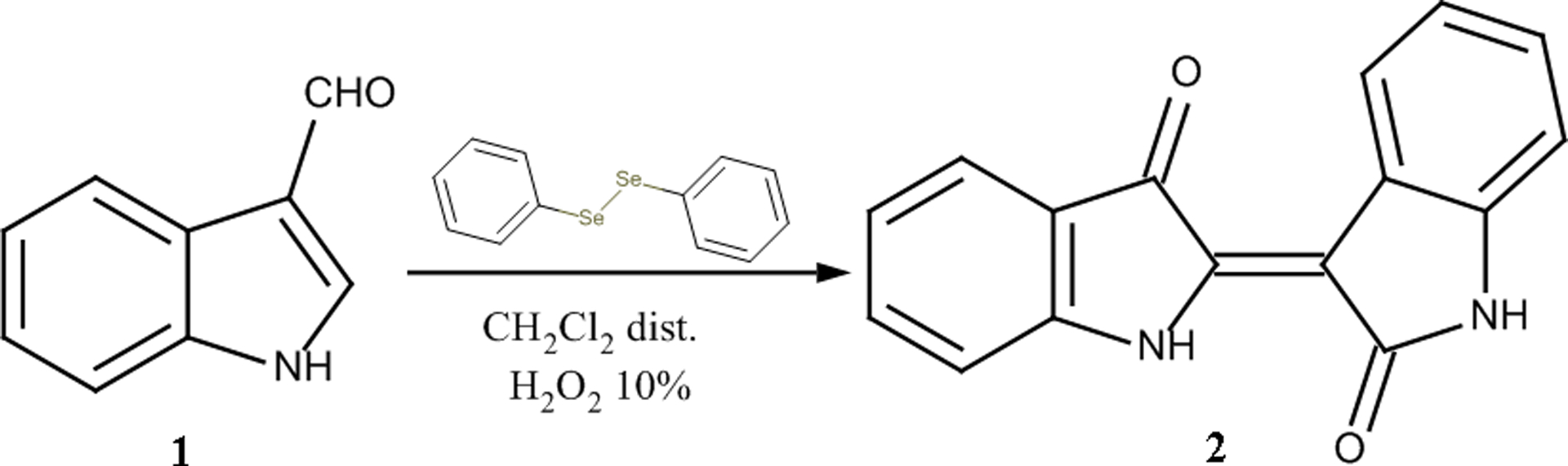

The performance of the initial reaction led to the formation and isolation of indirubin (2) after treatment of I3A (1) with H2O2 under Baeyer-Villiger oxidation conditions (Figure 1). However, several practical difficulties were observed in the above reaction such as the need for renewal of the reagents in the course of the reaction or the way of evaluating its success. Therefore, we investigated the possible ameliorations that could increase the reaction yield.

Figure 1:

Initial attempt for the formation of indirubin (2)

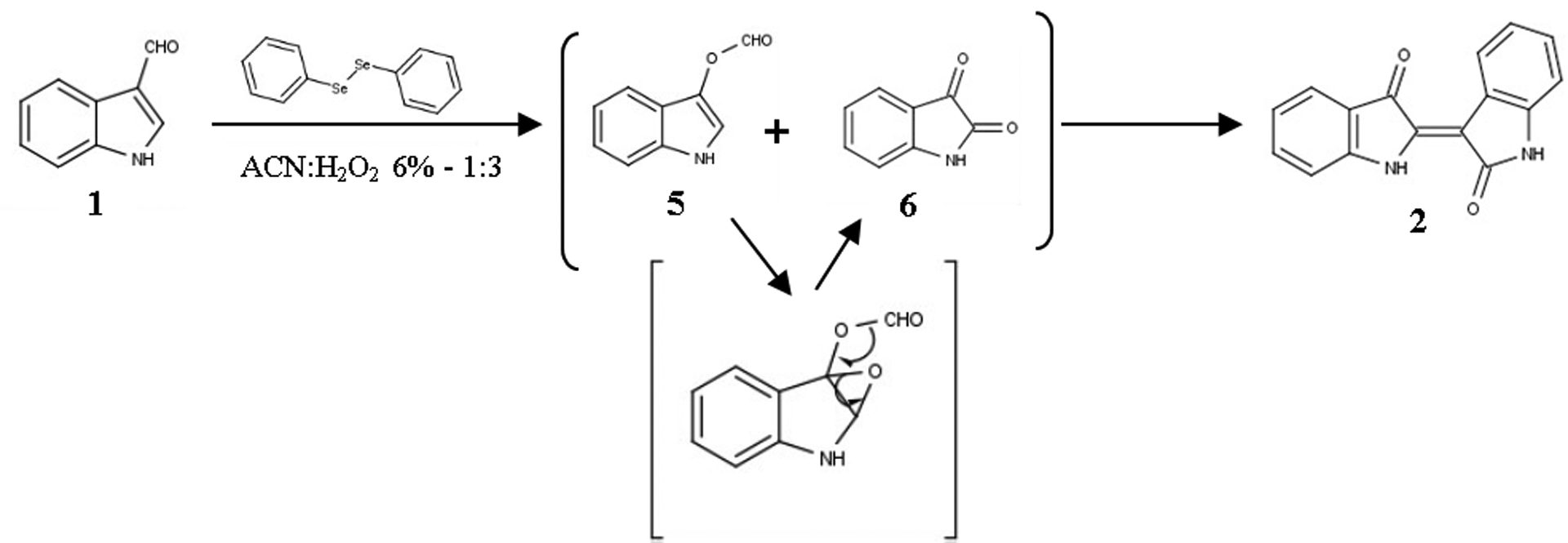

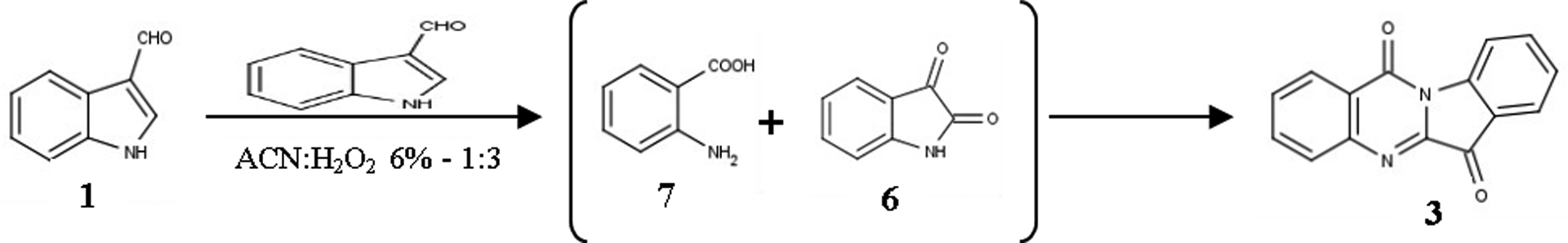

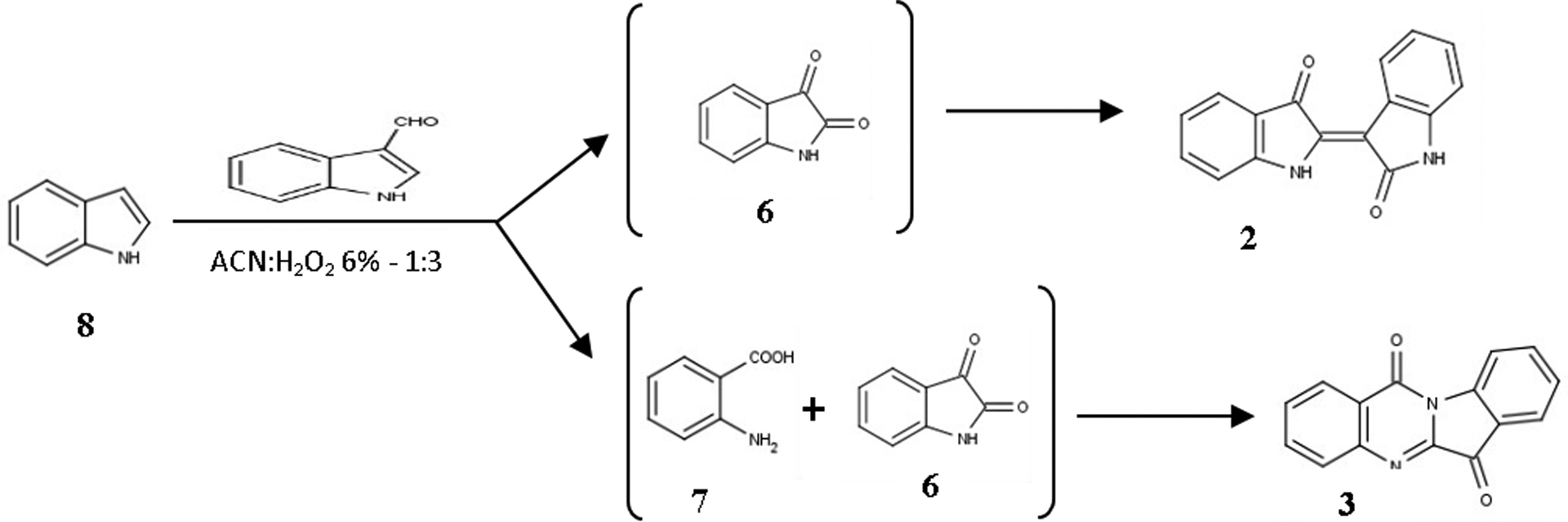

Modification of the reaction and application on I3A (1) and indole (8)

A reaction described by Santoro et al.11 was selected as alternative synthetic approach. It seemed preferable mainly due to its reagents, which were coinciding with the ones used for the transformation of I3A (1) to indirubin (2). According to this protocol, H2O2 has to be at a concentration of 6%, the solvent H2O:ACN in a ratio 3:1 and the optimal conditions are achieved when the selenium derivative is added in a catalytic amount (10%) and the reaction mixture is stirred for 72h at 23°C. This synthetic path is being characterized as an “eco-friendly olefin dihydroxylation”, probably due to the eco-friendly reagents used, and is proposed for the formation of vic diols (cis- or trans-) from the corresponding alkenes.

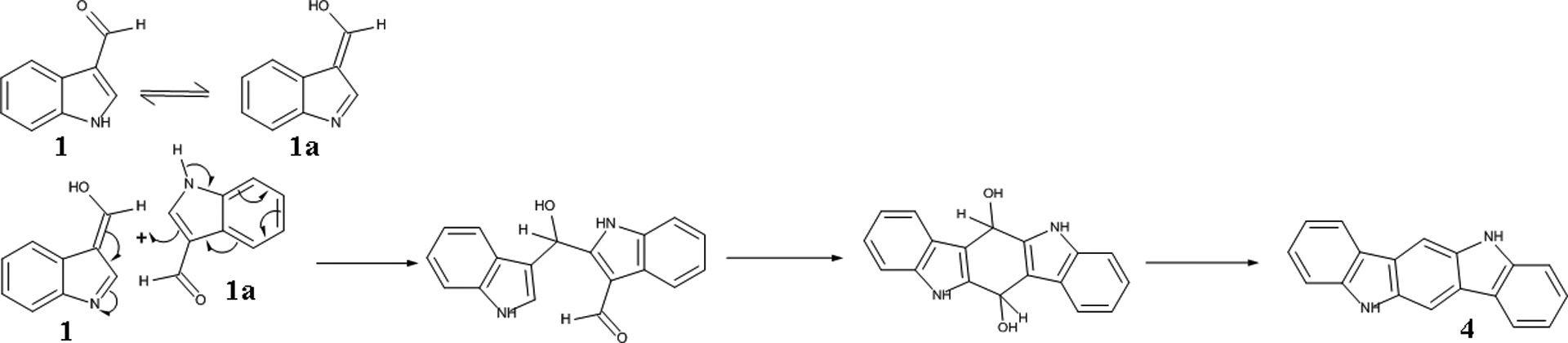

When the above conditions were applied on I3A (1), they resulted once again in the production of indirubin (2) along with a mixture of several co-products where a fluorescent yellow compound was predominant. The yellow compound was isolated and identified as indolo[2,1-b]quinazolin-6,12-dione or tryptanthrin (3) after comparison of its spectroscopic data with literature13. Tryptanthrin (3) is an already known AhR inducer which possesses also significant anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and cytostatic activity.24–30 It has been isolated from many plants as well as the yeast Candida (Yarrowia) lipolytica31–33 and has also been detected and isolated in Malassezia furfur yeasts.3, 4 Additionally, the spectroscopic analysis of the mixture showed the formation of indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4), another known Malassezia metabolite, in traces (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

General scheme of the biomimetic reaction

Those results prompted us to investigate further the optimal conditions for the reaction as well as its mechanism. During this effort, the reaction was also applied on simple indole (8), another abundant metabolite of Malassezia spp.5 and interestingly the formation of the metabolites 2 and 3 was also achieved, while indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4) was not detected.

Optimization of the reaction conditions

The successful application of the oxidation on indole (8) and I3A (1) paved the road for a further investigation of the optimal reaction conditions as well as for the role of each reagent. For this reason, several trials were performed and the attempts are summarized in Table 1. Further details on the optimization of the reaction conditions are presented as supporting information.

Synthesis of tryptanthrin and indirubin derivatives

After the described synthesis was successfully applied on indole (8) and I3A (1) and the optimal reaction conditions were clarified, the next step was the application on substituted indoles and indole-3-carbaldehydes. A wide variety of substituted indole compounds bearing halogens, alkyl-, hydroxyl-, alkoxy-, carboxymethyl- and amino- groups in positions 4, 5, 6 or 7 of the indole ring was chosen to be studied.

The most active among them seemed to be the compounds with substituents in positions 5 or 6 of the core and, especially, the ones that bore halogens, alkyl- and carboxymethyl- groups. This observation let us proceed in the synthesis of all the corresponding bisubstituted indirubins and tryptanthrins in yields that varied from 5 to 17% for indirubins (2–2g) and from 10 to 27% for tryptanthrins (3–3g), depending on the substitution. The highest yields for both molecules were achieved when 5- and 6-carboxymethylindoles were used as reactants. On the contrary, the application of this protocol on indoles bearing easily oxidizable groups (e.g. amino-, cyano-, hydroxyl- or methoxy- groups), led to the formation of dark colored, non-soluble precipitates. Furthermore, the reaction didn’t evolve as predicted when applied on either azaindoles or compounds with substituents in positions 4 or 7 of the indolic core.

Yet, another reaction performed on the mixture of I3A (1) and 6-bromo-I3A resulted in the simultaneous synthesis of all 8 bis-, mono- and unsubstituted analogues of the two alkaloids. Amongst the monosubstituted compounds, the formation of 6’-bromoindirubin and 3-bromotryptanthrin was favored by the reaction conditions, probably due to differences in the kinetics of the reactions.

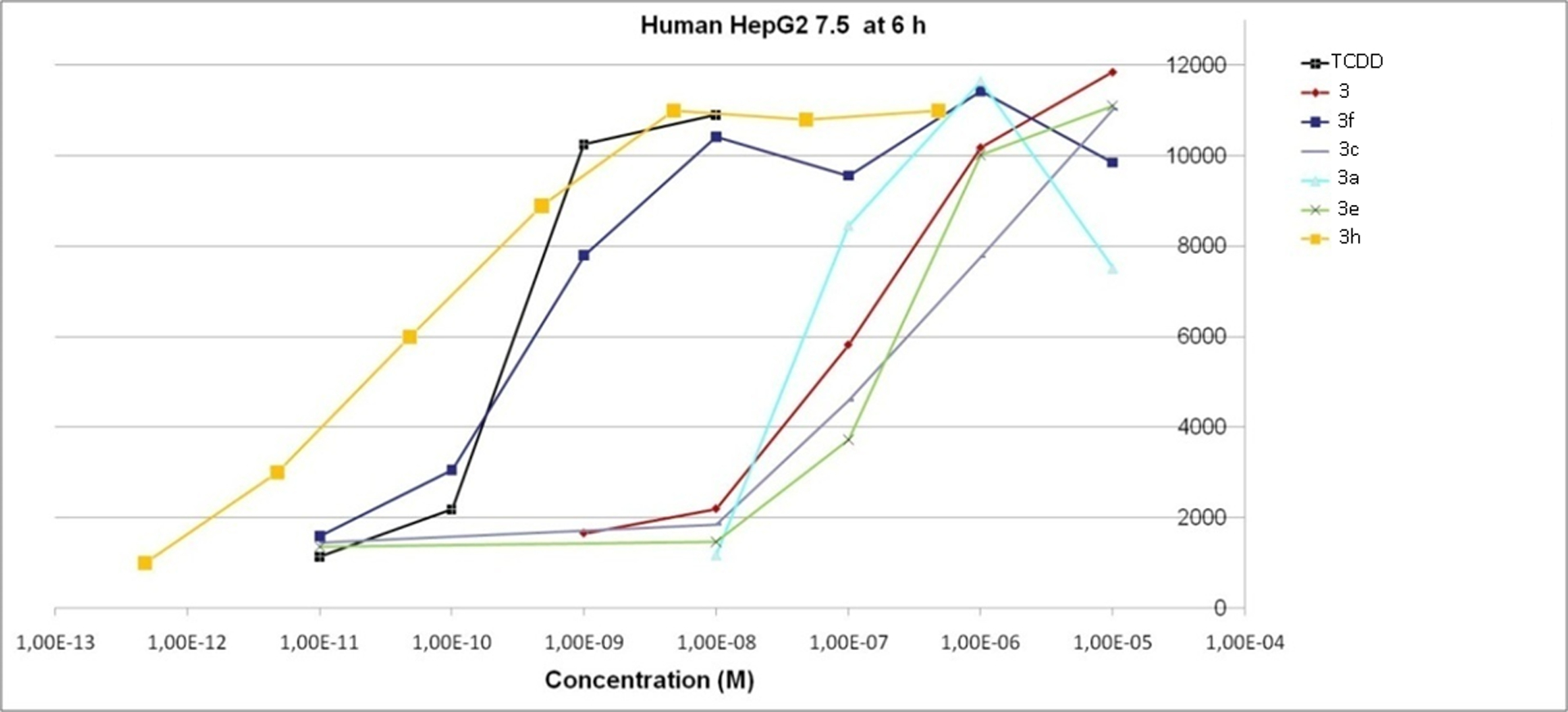

Evaluation of AhR Agonist Activity

The AhR agonist activity of 15 out of the 18 synthesized compounds was evaluated in recombinant HG2L7.5c1 human hepatoma cells containing a stably transfected AhR-responsive luciferase reporter gene.22 Indirubins were tested only in the human cell line due to previous evidence for the high selectivity of indirubins for the human AhR as compared to the mouse AhR.3, 34, 35 In contrast, tryptanthrin analogues were tested in both stably transfected human (HG2L7.5c1) and mouse (H1L7.5c3)hepatoma cell lines, not only to determine their relative potencies and efficacies, but also to evaluate whether these analogues also exhibited a greater selectivity for human AhR compared to mouse AhR. The 6 hour concentration-response results of tryptanthrins obtained using the human HG2L7.5c1 cells are presented in Figure 3. The EC50 (M) results from concentration response curve for the indirubins and tryptanthrins were calculated and compared to the EC50 (M) obtained from TCDD concentration response analysis (Tables 5 and 6).

Figure 3:

Concentration-response analysis of the induction of AhR-dependent luciferase reporter gene expression in human hepatoma (HG2L7.5c1) cells by TCDD, tryptanthrin and tryptanthrin analogues. See Table 4 for specific chemical substitutions.

Table 5:

EC50values for the induction of AhR-dependent gene expression in human hepatoma (HG2L7.5c1) cells by Indirubins

| |

|---|---|

| EC50, 6h Human | |

| 2 | 2.8×10−11 |

| 2a | 1.0×10−9 |

| 2b | 3.0×10−10 |

| 2e | 8.2×10−8 |

| 2f | 8.6×10−10 |

| 2g | 1.0×10−6 |

| TCDD | 5.7×10−10 |

Table 6:

EC50values for the induction of AhR-dependent gene expression in human (HG2L7.5c1) and mouse (H1L7.5c3) hepatoma cell lines by tryptanthrins.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| EC50, 6h Human Cells | EC50, 6h Mouse Cells | |

| 3 | 1.7×10−7 | 8.1×10−7 |

| 3a | 5.4×10−8 | 2.0×10−6 |

| 3b | 8.4×10−8 | 9.1×10−7 |

| 3c | 5.6×10−7 | 3.6×10−6 |

| 3d | 6.8×10−8 | 7.2×10−7 |

| 3e | 4.5×10−7 | 3.7×10−6 |

| 3f | 4.9×10−10 | 3.9×10−7 |

| 3g | Inactive | Inactive |

| 3h | 5.7×10−11 | >1.0×10−6 |

| TCDD | 5.7×10−10 | 1.0×10−10 |

While most of the synthesized indirubins showed very strong activity (two of them (2b, 2f) had potencies comparable to or greater than TCDD), insertion of substituents reduced activity in comparison to the highly potent unsubstituted indirubin (Table 5). Concerning the tryptanthrin analogues, it is clear that this skeleton can afford extremely active derivatives with very simple modifications.

Among the tryptanthrin derivatives (Table 6), 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin (3f) interestingly showed a 350-fold increased potency compared to tryptanthrin (3) in the human HG2L7.5c1 cells and was comparable to the potency of TCDD when evaluated at 6h (EC50 5×10−10M. In contrast, the monosubstituted analogue 3h (3-bromotryptanthrin) was 3,000-times more potent than tryptanthrin and 10 times more potent than TCDD in the human cells. Given the previously documented high degree of selectivity of indirubin for human AhR, as compared to mouse AhR,3,34,35 and similarities in several structural aspects of indirubin and tryptanthrin, the relative potencies of tryptanthrin analogues in human and mouse cells were compared. These analyses revealed that while most tryptanthrin analogues were about 10-fold less potent in the mouse cell line, as compared to that of the human cell line, all were significantly less potent than TCDD in the mouse cells (Table 6, Figure 4). Interesting, 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin and 3-bromotryptanthrin were 4,000- and 10,000-fold less potent in the mouse cells, respectively, than in the human cells, where these compounds were equipotent to or more potent than TCDD (Table 6, Figure 4). These results clearly demonstrate that 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin and 3-bromotryptanthrin are highly potent and efficacious human selective AhR agonists.

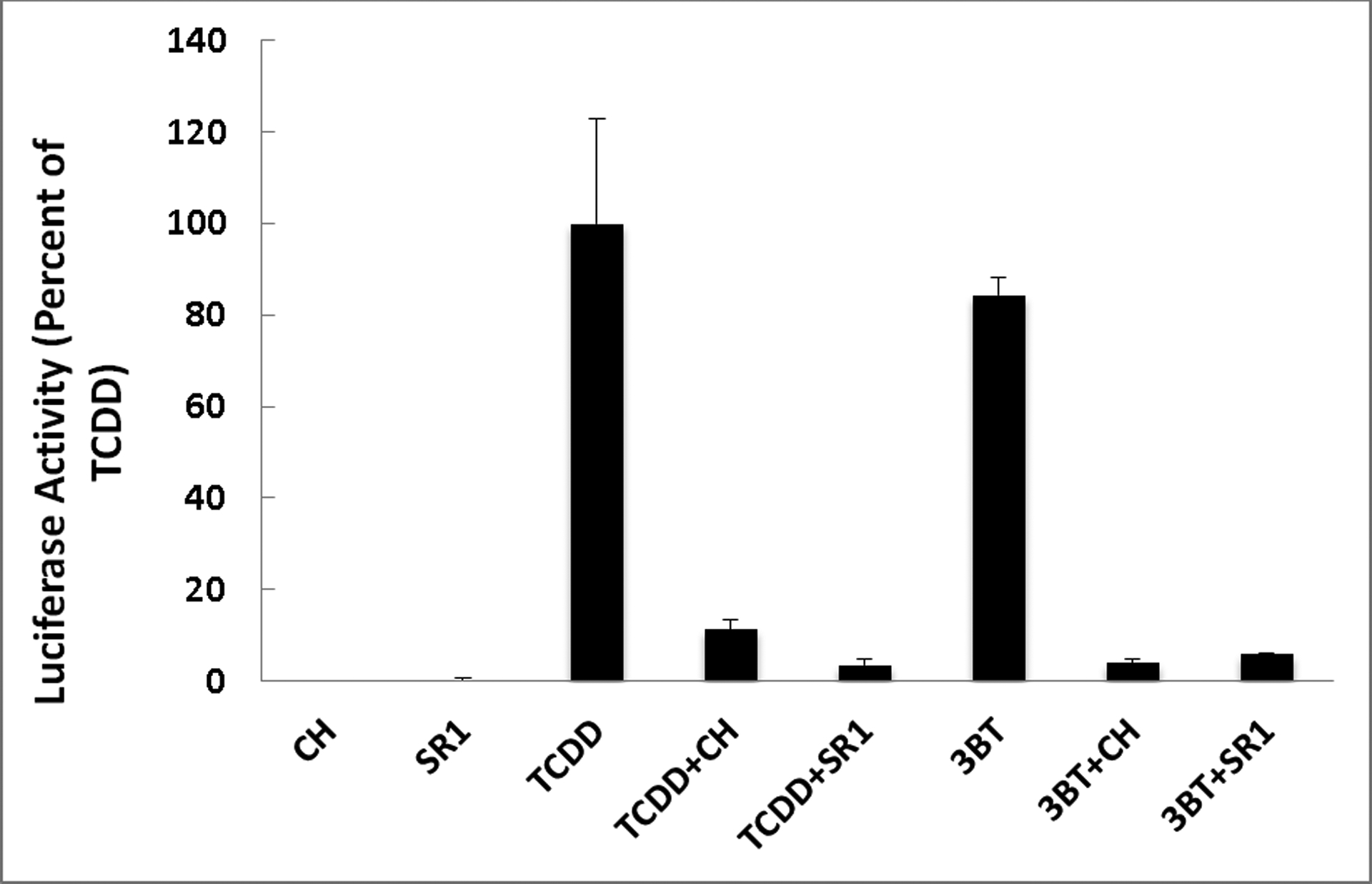

Figure 4:

The AhR antagonists CH223191 (CH) and StemRegenin1 (SR1) inhibit TCDD- and 3BT-dependent induction of luciferase reporter gene expression in recombinant human hepatoma (HG2L7.5c1) cells.

To confirm that the induction of reporter gene expression in human cells was mediated by the AhR, the effect of AhR antagonists (CH223191 and SR136,37 on the induction of reporter gene expression by 3-bromotryptanthrin was examined in the human HG2L7.5c1 cells (Figure 4). These results clearly demonstrate that AhR antagonists inhibit both TCDD- and 3-bromotryptanthrin-dependent reporter gene induction in the human cell line, consistent with these responses being mediated by the AhR

The gene induction experiments were carried out at 6h of incubation due to the metabolic lability of the tryptanthrins.

At 24h of incubation, the EC50 for gene induction in human cells by TCDD remained as low as 3×10−10 M but the potency of tryptanthrins was significantly reduced (EC50s of 10−6 to 10−7) and this results from differences in the metabolism of these compounds. While TCDD cannot be metabolized to any significant degree and therefore its relative potency is retained at 24h, tryptanthrins are metabolized by the CYP enzymes induced in these cells, resulting in induction of AhR-dependent gene expression that is transient, with a maximum peak between 6h and 12h.

Discussion

Here we describe the one-step transformation of the aldehyde 1 and/or indole (8) to the alkaloids indirubin (2) and tryptanthrin (3), under Baeyer-Villiger oxidation conditions.

As already analyzed, the established reaction protocol is the result of an amelioration process, with one of the most important and consistent characteristics to be the catalyst used, diphenyl diselenide, the reaction of which with H2O2 results in the in situ formation of the corresponding seleninic acid (aka Syper method of activation).38–40 The necessity for further investigation and optimization of the procedure led us to perform an extensive bibliographic search on oxidation of indoles and on reactions using either H2O2 as an oxidative means or organic derivatives of selenium as a catalyst, identified a number of different relevant publications.

We chose to follow the procedure as it is described by Santoro et al.11 as it combined the use of H2O2 and diphenyl diselenide with the organoselenic derivatives to be a category of catalysts preferred in several organic reactions due to their easy synthesis and their stability under various conditions. Throughout this protocol, we achieved the one-step transformation of the aldehyde 1 to the alkaloids 2 and 3 in good yields and the compound 4 in traces. This can be considered as a biomimetic reaction, showing for the first time the possible common biosynthetic origin of the three metabolites (Figure 2), assumption that is verified by the synthesis of the same two out of three alkaloids when indole (8), also a metabolite found in abundance in Malassezia cultures, was used as starting material. The one-pot conversion of both I3A (1) and indole (8) to indirubin (2) and tryptanthrin (3) simultaneously via the same oxidative reaction has never been reported.

The up-to-date data on the oxidation of indoles refer to studies conducted in many different ways, using a variety of reagents (usually expensive and difficult to handle) and leading mainly to the formation of the corresponding 2-indolinones or oxindoles.41,42,45,47 In some cases also isatin50 or indigo were formed.48,49 Additional research on the attempted syntheses of the two alkaloids revealed that both are formed by the coupling of an isatin (5) molecule with either 3-acetoxyindole for indirubin (2)53or isatoic anhydride for tryptanthrin (3).31,54,55 Many other alternative paths have been used for the synthesis of 3, including even electrochemical methods and condensation of isatin (5).31, 56–60 A review on the synthetic and medicinal advances for tryptanthrin has been recently published, summarizing most of the available methods for tryptanthrin synthesis.61 Among the most recent publications, some newer interesting methods for the synthesis of thryptanthrin (3) were described that are very similar to the aforementioned biomimetic reaction. In two of them, I3A (1) was submitted to oxidative dimerization using either Oxone in a mixture of water and ACN62 or urea peroxide in toluene.63 Especially the last one is very efficient for tryptanthrin but not for indirubin and probably this is related with the use of toluene and heat that make the reaction conditions much more different than those used in our case which are closer to those of a living organism (aqueous medium and ambient temperature). Three more publications have used indole (8) as starting material which is dimerized either with copper iodide as a catalyst under a continuous flux of oxygen15 or via irradiation by LED light combined with the use of selected catalysts and simultaneous exposure to oxygen.19,64

However, the developed synthetic protocol followed in our case seems to have certain advantages. This synthetic path is being described as an “eco-friendly olefin dihydroxylation” leading to the formation of vic diols from the corresponding alkenes.11 The eco-friendly character of the reaction is of great importance and reassured by the solvents (water and ACN) and the reagents (H2O2 and (PhSe)2) used, that are not harmful for the environment, especially after the treatment of the residue. Other advantages are the simple overall procedure, the low-cost, easily accessible reagents and the possibility of application on a significant number of substrates, comprising both indoles and indole-3-carbaldehydes. All these features, along with the simultaneous formation of two different categories of alkaloids, establish the reaction as an attractive alternative for their synthesis. To the very best of our knowledge, the successful application of the same dimerization reaction on both indole (8) and I3A (1) hasn’t been reported before whereas the parallel synthesis of both indirubin (2) and tryptanthrin (3) has been mentioned only once again,62 where indirubin (2) is referred to as one of the byproducts of the reaction.

The mechanism that mediates the oxidative transformation of I3A (1) and indole (8) is difficult to be confirmed with certainty. A primary concept can be based on the mechanism described by Santoro, involving the formation of an intermediary epoxide which then opens to the cis- or trans- diol11 and the catalyst is reborn through this cycle.

In accordance to the above assumption, we came up with a hypothesis involving the synthesis of 3-indolyl formate (5), which would be originally expected under Bayer-Villiger conditions, and the subsequent formation of an intermediary epoxide on the double bond of the positions 2 and 3. Hydrolysis of the intermediate results in isatin (6), creating thus an equilibrium between the indole derivatives 5 and 6, the coupling of which gives indirubin (3). This mechanism is depicted in Figure 5 and is close to a well-known methodology of indirubin (3) synthesis53 which involves a coupling reaction between 3-acetoxyindole and isatin (6).

Figure 5:

Proposed mechanism for the formation of Indirubin (2)

A quite similar mechanism is proposed for the synthesis of tryptanthrin (3) which is thought to be produced by the coupling reaction between anthranilic acid (7) and isatin (6). As mentioned, isatin (6) is formed in the reaction medium, whereas anthranilic acid (7) can result by the hyperoxidation of either I3A (1) or isatin (6) and subsequent in situ formation of the isatoic anhydride which will be hydrolyzed to yield the acid 7, a hypothesis supported by previous bibliographic data.60 This synthetic path is shown in Figure 6 and the concept behind this proposed mechanism is similar to the ones suggested by the most relevant publications.15, 62, 63,

Figure 6:

Proposed mechanism for the formation of Tryptanthrin (3)

It’s worth mentioning that, like in the case of indirubin (2), the reaction between anthranilic acid (7) and isatin (6) is a common synthetic method for the production of tryptanthrin (3),65,66 with distinct reference to the biosynthesis of the alkaloid.31 However, when an ACN solution of the proposed intermediates isatin (6) and anthranilic acid (7) was stirred for 72h at 23°C none of the desirable alkaloids were formed, suggesting the necessity of an oxidative means in the reaction medium, an assumption that is also in accordance with bibliographic data.60, 65, 66

The aforementioned synthetic schemes represent largely the assumed mechanisms for the transformation of indole (8) to the two alkaloids when the exact same reaction conditions. The hypothesis is slightly altered, involving the condensation of two molecules of the produced isatin (6). This is supported also by recent data that describe the synthesis of indirubins by isatin coupling in reductive conditions.14 The proposed synthetic scheme for this reaction is in Figure 7.

Figure 7:

Proposed mechanism for the transformation of indole (8)

As far as the formation of indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4) is concerned, a different mechanism is proposed, involving the direct coupling of two I3A (1) units (Figure 8) and is based on relevant bibliographic data.9, 67–70 As it has already been mentioned, compound 4 is formed only in the reaction of I3A (1). This observation can be easily explained as indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4) is a molecule with 18 carbon atoms whilst the dimerization of indole (8), can offer only up to 16 carbon atoms in the reaction. On the other hand, in the reaction of I3A (1) the carbon atoms participating are sufficient enough for the formation indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4).

Figure 8:

Proposed mechanism for the formation of Indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4)

Summing up the details of the reaction mechanism, we need to state the importance of the order of addition of the reagents as, according to the general reaction mechanism proposed11, the catalyst has first to be activated meaning that the reaction of the oxidative means with the catalyst has to take place prior to its reaction with the starting material. For this reason, the addition of H2O2 in the solution of the catalyst before the reactant is mandatory.

Finally, examining the products resulting from the reaction on the mixture of I3A (1) and 6-bromo-I3A (8) we observed the favored synthesis of certain compounds; combined with the mechanisms proposed, they can lead to some remarks for the kinetics of the transformations. Given the bibliographic data31, 71 the 6’-substitution on indirubin scaffold derives from the substitution of acetoxyindole and, respectively, the 3-subsitution on tryptanthrin from the anthranilic acid (7). Our observation can suggest that the reaction for the formation of 6-bromoisatin (10) progresses more slowly than the corresponding acetoxyindole (9) and anthranilic acid (11), favoring thus the one for the non-acylated compound (Figure 9). According to this hypothesis, the synthesis of 6’-bromoindirubin (2h) and 3-bromotryptanthrin (3h) seems to be favored compared to the 6- and 9- substituted compounds.

Figure 9:

Proposed mechanism for the formation of the monosubstituted derivatives 2h and 3h

The final step of this work comprised the evaluation of the AhR agonist activity of the purified indirubin and tryptanthrin analogues and revealed some interesting results for these classes of alkaloids. Although most of the synthesized indirubin analogues were relatively potent AhR agonists, all of the resulting compounds were less potent than that of unsubstituted indirubin. Additionally, it was clear that even simple modification of the tryptanthrin skeleton could produce analogues that are extremely potent and efficacious AhR agonists, particularly in the human cell line.

The tryptanthrin structure activity relationship bioassay results in human cells revealed that insertion of bromine at positions 3 and 9 (3f) not only increased the relative potency (EC50) of unsubstituted tryptanthrin (3) from 170 nM to 490 pM, but induced maximal AhR-dependent reporter gene activity (Figure 3). These observations are significant in that the relative potency and efficacy of the 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin as an AhR agonist in human cells is comparable to that of TCDD, the prototypical and one of the most potent known AhR agonists. Even more significant is that a tryptanthrin analogue with only a single bromine at position 3 (3-bromotryptanthrin (3h)) had a relative potency in human cells that was even 10-fold higher (57 pM), not only suggesting that the additional bromine at position 9 in compound 3f actually reduced the overall relative AhR affinity/potency compared to that of compound 3h, but producing a compound that was 10-fold more potent than TCDD. 3-Bromotryptanthrin (3h) was also found to be a highly efficacious AhR agonist, stimulating AhR-dependent reporter gene expression to a level comparable to that produced by a maximally inducing concentration of TCDD (Figure 3). Previous mutagenesis and molecular docking analysis studies have clearly demonstrated that some specific interactions of a ligand with residues within the AhR ligand binding site are critical and can drive ligand-selective interactions,72–75 such that a simple modification like the insertion of a carbomethoxy group in the same scaffold positions (3g) instead of bromine can lead to a completely inactive derivative. While induction of reporter gene expression in the human cells by a given compound strongly suggests that it is an AhR agonist and activates reporter gene expression via the AhR, the role of the AhR in the ability of the most potent tryptanthrin analogue (3-bromotryptanthrin (3h)) was confirmed by demonstrating the ability of two AhR antagonists (CH223191 and SR1) to inhibit the induction response (Figure 4). Together, these analyses have identified two new and novel tryptanthrin analogues (3-bromotryptanthrin and 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin) as highly potent and efficacious agonists of the human AhR and AhR signaling pathway.

Studies from several laboratories have demonstrated that indirubin is a highly potent and efficacious human-selective AhR agonist that induces AhR-dependent gene expression in human cells with an EC50 that is ~10-fold greater than that of TCDD.3, 34, 35, 76 In contrast, in mice or mouse cells, indirubin is ~100-less less potent than TCDD, but still highly efficacious.34, 35, 76 Site-directed mutagenesis and functional analysis studies have identified specific amino acid residues within the mouse and human AhR ligand binding pockets that contributes to this differential specificity and responsiveness.35 The similarities in structual aspects of indirubins and tryptanthrins suggest that similar species differences in tryptanthrin ligand specificity may also exist. Comparison of the relative potencies of the indirubins (3–3h) to stimulate AhR-dependent reporter gene analysis in both human and mouse hepatoma cell lines containing the identical reporter gene plasmid (Table 6) revealed that while the potency of tryptanthrin (3) was comparable between human and mouse cell lines, all tryptanthrin analogues were less potent in the mouse cell lines. The divergent species-specificity was particularly evident for the tryptanthin analogues that were most potent human AhR agonists (i.e., 3-bromotryptanthrin (3h) and 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin (3f)). While 3-bromotryptanthrin (3h) was 10-times more potent than TCDD in human cells, it was 10,000-times less potent than TCDD in the mouse cells; the difference in relative AhR agonist potency between the human and mouse cells was >17,000-fold (Table 6). Similarly, although 3,9-dibromotryptanthrin (3h) was equipotent to that of TCDD in human cells, it was 4,000-times less potent than TCDD in the mouse cells; the difference in relative AhR agonist potency between the human and mouse cells was ~800-fold (Table 6). These results confirm that these two tryptanthrin analogues, like indirubin, are human-selective AhR agonists. However, the AhR antagonist results with 3-bromotryptanthrin suggest that it interacts with residues within the AhR ligand binding pocket in a manner that is distinctly different than that of indirubin. Previous studies have demonstrated that while the AhR antagonist CH223191 could effectively inhibit the ability of TCDD to bind to and activate the AhR, this antagonist had little effect on AhR activation by indirubin,37 suggesting that TCDD and indirubin differentially interact with residues within the AhR ligand binding domain. The ability of CH223191 to inhibit AhR-dependent reporter gene activity by both TCDD and 3-bromotryptanthrin (Figure 5) suggests that binding of 3-bromotryptanthrin to the AhR is more similar to that of TCDD than indirubin, which is not inhibited by CH223191. However, since 3-bromotryptanthrin is a more potent AhR activator of the human AhR than TCDD and a much less potent activator of the mouse AhR than TCDD, 3-bromotryptanthrin must interact with the AhR ligand bidning pocket in a manner similar to, but distinctly different from that of TCDD; the differences in potency of TCDD between the human and mouse cell lines was only ~6-fold (Table 6). These induction and inhibition responses suggest that 3-bromotryptanthrin (and perhaps other tryptanthrins) may represent a novel group of AhR agonists that interact with residues within the AhR ligand binding pocket in a manner distinctly different from TCDD, indirubin and other ligands characterized to date.34, 35, 73–78. However, further detailed QSAR and docking analysis of these analogues into both human and mouse AhR ligand binding sites generated by molecular modeling are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms responsible for the high affinity/potency of selected tryptanthrins and the dramatic species differences in ligand specificity.

Conclusion

The total of the collected data is of significant chemical and toxicological value. The synthesis of all three alkaloids -indirubin (2), tryptanthrin (3) and indolo[3,2-b]carbazole (4)- through the same oxidative mechanism from I3A (1), the main product of L-tryptophan metabolism in Malassezia yeasts, seems to be used also by the fungus for the production of these secondary metabolites which are implicated in the Malassezia-related skin diseases. Taking into consideration that indirubin (2) and tryptanthrin (3) are often together isolated from several plant species, like Isatis spp. and Polygonum tinctorium,78,79 the existence of a common biosynthetic path for the two metabolites is a reasonable hypothesis. The inhibition of the oxidative transformation of I3A to indirubin and tryptanthrin by Malassezia could be a potential future target for the inhibition of Malassezia toxicity to skin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by grants (to MSD) form the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES07685; P42ES004699) and the California Agriculture Experiment Station.

Abbreviations

- AhR

Aryl-hydrocarbon Receptor

- I3A

Indole-3-carbaldehyde

- H2O2

Hydrogen Peroxide

- ICZ

Indolo[3,2-b]carbazole

- 6-FICZ

6-Formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole

- NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- TLC

Thin Layer Chromatography

- DCM

Dichrolomethane

- (PhSe)2

Diphenyl diselenide

- THF

Tetrahydrofuran

- Rf

Retardation factor

- EtOAc

Ethyl Acetate

- (CD3)2SO

Deuterated Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- CDCl3

Deuterated Chloroform

- EC50

Half maximal effective concentration

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin

- α-MEM

alpha-minimum essential media

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- DMSO

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- ACN

Acetonitrile

- CYP

Cytochrome P450

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Analytical data for the synthesized compounds and results of the optimization trials and reaction mechanism investigation

REFERENCES

- (1).Gaitanis G, Magiatis P, Hantschke M, Bassukas ID and Velegraki A (2012) The Malassezia genus in skin and systemic diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 25, 106–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gaitanis G, Magiatis P, Stathopoulou K, Velegraki A, Bassukas I, Alexopoulos E, and Skaltsounis AL (2008) AhR ligands, malassezin, and indolo[3,2-b]carbazole are selectively produced by Malassezia furfur strains isolated from seborrheic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol 128, 1620–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Magiatis P, Pappas P, Gaitanis G, Mexia N, Melliou E, Galanou M, Vlachos C, Stathopoulou K, Skaltsounis AL, Marselos M, Velegraki A, Denison MS, and Bassukas ID (2013) Malassezia Yeasts Produce a Collection of Exceptionally Potent Activators of the Ah (Dioxin) Receptor Detected in Diseased Human Skin. J. Invest. Dermatol 133, 2023–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Mexia N, Gaitanis G, Velegraki A, Soshilov A, Denison MS, and Magiatis P (2015) Pityriazepin and other potent AhR ligands isolated from Malassezia furfur yeasts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 571, 16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wille G, Mayser P, Thoma W, Monsees T, Baumgart A, Schmitz HJ, Schrenk D, Polborn K, and Steglich W (2001) Malassezin-a novel agonist of the Arylhydrocarbon Receptor from the yeast Malassezia furfur. Bioorg. Med. Chem 9, 955–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mexia N, Magiatis P, Gaitanis G, Velegraki A, and Skaltsounis AL (2011) Synthesis, detection and quantification of the highly active AhR ligands tryptanthrin, indirubin and indolo[3,2-b]carbazol in Malassezia yeasts. Planta Med. 77, WSII5. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Syper L (1987) Reaction of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes with hydrogen peroxide catalysed by benzeneseleninic acids and their precursors. Tetrahedron 43, 2853–2871. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Halliwell B, Clement MV, and Long LH (2000) Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 486, 10–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Smirnova A, Wincent E, Vikström Bergander L, Alsberg T, Bergman J, Rannug A and Rannug U (2016) Evidence for New Light-Independent Pathways for Generation of the Endogenous Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist FICZ. Clin. Res. Toxicol 29, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).KanehisaLaboratories. (2018) KEGG PATHWAY: Tryptophan metabolism - Reference pathway, In KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, Kanehisa Laboratories. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Santoro S, Santi C, Sabatini M, Testaferri L, and Tiecco M (2008) Eco-Friendly olefin dihydroxylation catalyzed by diphenyl diselenide. Adv. Synth. Catal 350, 2881–2884. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Adachi J, Yosimoto M, Matsui S, Tagikami H, Fujino J, Kitagawa H, Miller CA, Kato T, Saeki K, and Matsuda T (2001) Indirubin and Indigo Are Potent Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligands Present in Human Urine. J. Biol. Chem 276, 31475–31478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Jao CW, Lin WC, Wu YT, and Wu PL (2008) Isolation, structure elucidation, and synthesis of cytotoxic tryptanthrin analogues from Phaius mishmensis. J. Nat. Prod 71, 1275–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang C, Yan J, Du M, Burlison JA, Li C and Sun Y (2017) One step synthesis of indirubins by reductive coupling of isatins with KBH4. Tetrahedron 73, 2780–2785. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang C, Zhang L, Ren A, Lu P, and Wang Y (2013) Cu-Catalyzed Synthesis of Tryptanthrin derivatives from Substituted Indoles. Org. Lett 15, 2982–2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Riepl HM, and Urmann C (2012) Improved Synthesis of Indirubin Derivatives by Sequential Build-Up of the Indoxyl Unit: First Preparation of Fluorescent Indirubins. Helv. Chim. Acta 95, 1461–1477. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Beauchard A, Ferandin Y, Frère S, Lozach O, Blairvacq M, Meijer L, Thiéry V, and Besson T (2006) Synthesis of novel 5-substituted indirubins as protein kinases inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem 14, 6434–6443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Clark RJH, and Cooksey CJ (1997) Bromoindirubins: the synthesis and properties of minor components of Tyrian purple and the composition of the colorant from Nucella lapillus. J.S.D.C 113, 316–321. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Li X, Huang H, Yu C, Zhang Y, Li H and Wang W (2016) Synthesis of Tryptanthrins by Organocatalytic and Substrate Co-catalyzed Photochemical Condensation of Indoles and Anthranilic Acids with Visible Light and O2. Org. Lett 18, 5744–5747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Karkoula E, Skantzari A, Melliou E, and Magiatis P (2012) Direct Measurement of Oleocanthal and Oleacein Levels in Olive Oil by Quantitative 1H NMR. Establishment of a New Index for the Characterization of Extra Virgin Olive Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem 60, 11696–11703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).He G, Tsutsumi T, Zhao B, Baston DS, Zhao J, Heath-pagliuso S and Denison MS (2011) Third-generation ah receptor-responsive luciferase reporter plasmids: Amplification of dioxin-responsive elements dramatically increases CALUX bioassay sensitivity and responsiveness. Toxicol. Sci 123, 511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Brennan JC, He G, Tsutsumi T, Zhao J, Wirth E, Fulton MH and Denison MS (2015) Development of Species-Specific Ah Receptor-Responsive Third Generation CALUX Cell Lines with Enhanced Responsiveness and Improved Detection Limits. Environ. Sci. Technol 49, 11903–11912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).He G, Zhao J, Brennan JC, Affatato AA, Zhao B, Rice RH and Denison MS (2014) Cell-based assays for identification of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) activators, In Methods in Pharmacology and Toxicology pp 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Schrenk D, Riebniger D, Till M, Vetter S, and Fiedler HP (1997) Tryptanthrins: A novel class of agonists of the Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol 54, 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kimoto T, Yamamoto Y, Hino K, Koya S, Aga H, Hashimoto T, Hanaya T, Arai S, Ikeda M, Fukuda S, and Kurimoto M (1999) Cytotoxic effects of substances in indigo plant (Polygonum tinctorium Lour.) on malignant tumor cells. Nat. Med. (Tokyo, Jpn.) 5 3, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kataoka M, Hirata K, Kunikata T, Ushio S, Iwaki K, Ohashi K, Ikeda M, and Kurimoto M (2001) Antibacterial action of tryptanthrin and kaempferol, isolated from the indigo plant (Polygonum tinctorium Lour.), against Helicobacter pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. J. Gastroenterol 36, 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hamburger M (2002) Isatis tinctoria – From the rediscovery of an ancient medicinal plant towards a novel anti-inflammatory phytopharmaceutical. Phytochem. Rev 1, 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chan HL, Yip HY, Mak NK, and Leung KN (2009) Modulatory effects and action mechanisms of tryptanthrin on Murine Myeloid Leukemia cells. Cell Mol. Immunol 6, 335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bandekar PP, Roopnarine KA, Parekh TR, Mitchell TR, Novak MJ, and Sinden RR (2010) Antimicrobial Activity of Tryptanthrins in Escherichia coli. J. Med. Chem 53, 3558–3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Pergola C, Jazzar B, Rossi A, Northoff H, Hamburger M, Sautebin L, and Werz O (2011) On the inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase product formation by tryptanthrin: mechanistic studies and efficacy in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol 165, 765–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Fiedler E, Fiedler HP, Gerhard A, Keller-Schierlein W, König WA, and Zähner H (1976) Stoffwechselprodukte von mikroorganismen. Synthese und biosynthese substituierter tryptanthrine. Arch. Microbiol 107, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Schindler F, and Zähner H (1972) Tryptanthrine, an antibiotic tryptophan derivative from Candida lipolytica (brief report). Zentralbl. Bakteriol., Abt. 1, Orig. A 220, 457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Batanero B, and Barba F (2006) Electrosynthesis of tryptanthrin. Tetrahedron Lett. 47, 8201–8203. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Flaveny CA, Murray IA, Chiaro CR and Perdew GH. (2009) Ligand selectivity and gene regulation by the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor in transgenic mice. Mol. Pharmacol 75, 1412–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Faber SC, Soshilov AA, Tagliabue SG, Bonati L and Denison MS (2018) Comparative in vitro and in silico analysis of the selectivity of indirubin as a human Ah receptor agonist. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19, E2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Boitano AE, Wang J, Romeo R, Bouchez LC, Parker AE, Sutton SE, Walker JR, Flaveny CA, Perdew GH, Denison MS, Shcultz PG and Cooke MP (2010) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science 329, 1345–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zhao B, DeGroot D, Hayashi A, He G and Denison MS (2010) CH223191 is a ligand-selective antagonist of the Ah (dioxin) Receptor, Toxicol. Sci 117, 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Syper L (1989) The Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of aromatic aldehydes and ketones with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by selenium compounds. A convenient method for the preparation of phenols. Synthesis 3, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- (39).ten Brink GJ, Vis JM, Arends IWCE, and Sheldon RA (2001) Selenium-Catalyzed Oxidations with Aqueous Hydrogen Peroxide. 2. Baeyer-Villiger Reactions in Homogeneous Solution. J. Org. Chem 66, 2429–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kürti L, and Czakó B (2005) Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation/Rearrangement, In In Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis pp 28–29, Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Horng AJ, and Yang SF (1975) Aerobic oxidation of indole-3-acetic acid with bisulfite. Phytochemistry 14, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Desarbre E, Savelon L, Cornec O, and Mérour JY (1996) Oxidation of Indoles and 1,2-Dihydro-3H-indol-3-ones. Tetrahedron 52, 2983–2994. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Jung ME, and Lazarova TI (1997) Efficient synthesis of selectively protected L-Dopa derivatives from L-Tyrosine via Reimer-Tiemann and Dakin reactions. J. Org. Chem 62, 1553–1555. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Manini P, d’Ischia M, Milosa M, and Prota G (1998) Acid-Promoted Competing Pathways in the Oxidative Polymerization of 5,6-Dihydroxyindoles and Related Compounds: Straightforward Cyclotrimerization Routes to Diindolocarbazole Derivatives. J. Org. Chem 63, 7002–7008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Vaskez E, and Payack JF (2005) Conversion of 1-Boc-indoles to 1-Boc-oxindoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 6549–6550. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Meenakshisundaram S, and Sarathi N (2007) Chromium (VI) catalyzed oxidation of indole in aqueous acetic acid. Indian J. Chem., Sect. A: Inorg., Bio-inorg., Phys., Theor. Anal. Chem 46A, 1778–1781. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Enache TA, and Oliveira-Brett AM (2011) Pathways of Electrochemical Oxidation of Indolic Compounds. Electroanal. 23, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Yamamoto Y, Inoue Y, Takaki U, and Suzuki H (2011) Development of a practical one-pot synthesis of indigo from indole. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 84, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lin GH, Chen HP, Huang JH, Liu TT, Lin TK, Wang SJ, Tseng CH, and Shu HY (2012) Identification and characterization of an indigo-producing oxygenase involved in indole 3-acetic acid utilization by Acinetobacter baumannii. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 101, 881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kavery M, Govindasamy C, and Johnson S (2013) A Kinetic Study on the Oxidation of Indole by Peroxomonosulphate in Acetonitrile Solvent. J. Korean Chem. Soc 57, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Skobelev IY, Kudrik EV, Zalomaeva OV Albrieux F, Afanasiev P, Kholdeeva OA, and Sorokin AB (2013) Efficient epoxidation of olefins by H2O2 catalyzed by iron “helmet” phthalocyanines. Chem. Commun 49, 5577–5579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Kumar A, Rao GK, Saleem F, and Singh AK (2012) Organoselenium ligands in catalysis. Dalton Trans. 41, 11949–11977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Meijer L, Skaltsounis AL, Magiatis P, Polychronopoulos P, Knockaert M, Leost M, Ryan XP, Vonica CA, Brivanlou A, Dajani R, Crovace C, Tarricone C, Musacchio A, Roe SM, Pearl L, and Greengard P (2003) GSK-3-Selective Inhibitors Derived from Tyrian Purple Indirubins. Chem. Biol 10, 1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Liu JF, Lee J, Dalton AM, Bi G, Yu L, Baldino CM, McElory E, and Brown M (2005) Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted 3H-quinazolin-4-ones. Tetrahedron Lett. 46, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Bergman J, Lindström JO, and Tilstam U (1985) The structure and properties of some indolic constituents in Couroupita Guianensis Aubl. Tetrahedron 41, 2879–2881. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Friedländer P, and Roschdestwensky N (1915) Über ein Oxidationsprodukt des Indigoblaus. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges 48, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Li Q, Jin J, Chong M, and Song Z (1983) Studies on the antifungal constituent of Qing Dai (Isatis indigotica). Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 14, 440–441. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Moskovkina TV (1997) New synthesis of 6,12-dihydro-6,12-dioxoindolo[2,1-b]quinazoline (tryptanthrine, couropitine A). Russ. J. Org. Chem 33, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Kumar A, Tripathi VD and Kumar P (2011) b-Cyclodextrin catalysed synthesis of tryptanthrin in water. Green Chem. 13, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Jia FC, Zhou ZW, Xu C, Wu YD and Wu AX (2016) Divergent synthesis of quinazolin-4(3H)‑ones and tryptanthrins enabled by a tert-butyl hydroperoxide/K3PO4‑promoted oxidative cyclization of isatins at room temperature. Org. Lett 18, 2942–2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Kaur R, Kaur MS, Rawal RK and Kumar K (2017) Recent synthetic and medicinal perspectives of tryptanthrin. Bioorg. Med. Chem 25, 4533–4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Nelson AC, Kalinowski ES, Jacobson TL, and Grundt P (2013) Formation of tryptanthrin compounds upon Oxone-induced dimerization of indole-3-carbaldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 54, 6804–6806. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Abe T, Itoh T, Choshi T, Hibino S, and Ishikura M (2014) One-pot synthesis of tryptanthrin by the Dakin oxidation of indole-3-carbaldehyde. Tetrahedron Lett. 55, 5268–5270. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Zhang C, Li S, Buresš F, Lee R, Ye X and Jiang Z (2016) Visible Light Photocatalytic Aerobic Oxygenation of Indoles and pH as a Chemoselective Switch. ACS Catal. 6, 6853–6860. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Jahng KC, Kim SI, Kim DH, Seo CS, Son JK, Lee SH, Lee ES and Jahng Y (2008) One-pot synthesis of simple alkaloids: 2,3-Polymethylene-4(3H)-quinazolinones, luotonin A, tryptanthrin, and rutaecarpine. Chem. Pharm. Bull 56, 607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Wang C, Hou B, Zhang N, Sun Y and Liu J (2015) Biomimetic Synthesis of Natural Product Tryptanthrin and Its Derivatives. Chem. J. Chinese U 36, 274–278. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Bergman J (1970) Condensation of indole and formaldehyde in the presence of air and sensitizers. Tetrahedron 26, 3353–3355. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Bergman J, Carlsson R, and Misztal S (1976) The reaction of some indoles and indolines with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone. Acta Chem. Scand 30b, 853–862. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Amat-Guerri F, Martinez-Utrilla, and Pascual C (1984) Condensation of 3-hydroxymethylindoles with 3-substituted indoles. Formation of 2,3′-methylennediidole-derivatives. J. Chem. Res. Synop, 160–161. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Bandgar BP, and Shaikh KA (2016) Molecular iodine-catalyzed efficient and highly rapid synthesis of bis(indolyl)methanes under mild conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 1959–1961. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Polychronopoulos P, Magiatis P, and Skaltsounis A-L (2004) Structural basis for the synthesis of indirubins as potent and selective inhibitors of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 and Cyclin-Dependent Kinases. J. Med. Chem 47, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).DeGroot DE, He G, Fraccalvieri D, Bonati L, Pandini A and Denison MS (2011) AhR Ligands: Promiscuity in Binding and Diversity in Response, In The Ah Receptor in Biology and Toxicology (Pohjanvirta R, Ed.) pp 63–79, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Motto I, Bordogna A, Soshilov A, Denison MS and Bonati L (2011) A new aryl hydrocarbon receptor homology model targeted to improve docking reliability, J. Chem. Info. Modeling 51, 2868–2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Soshilov AA and Denison MS (2014) Ligand promiscuity of aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists and antagonists revealed by site directed mutagenesis, Molec. Cell. Biol 34, 1707–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Giani Tagliabue S, Faber SC, Motta S, Denison MS and Bonati L (2018) Modeling the binding of diverse ligands within the Ah receptor ligand binding domain, Sci. Reports, 9; 10693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Flaveny CA and Perdew GH (2009) Transgenic human AhR mouse reveals differences between human and mouse AhR ligand selectivity, Molec. Cell. Pharmacol 1, 119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Fraccalvieri D, Soshilov AA, Karchner SI, Franks DG, Pandini A, Bonati L, Hahn ME and Denison MS (2013) Comparative analysis of homology models of the Ah receptor ligand binding domain: Verification of structure-function predictions by site-directed mutagenesis of a non-functional AhR. Biochem. 52, 712–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Honda G, Tosirisuk V, and Tabata M (1980) Isolation of an antidermatophytic, tryptanthrin, from the indigo plants, Polygonum tinctorium and Isatis tinctoria. Planta Med. 38, 275–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Hoessel R, Leclerc S, Endicott JA, Nobel ME, Lawrie A, Tunnah P, Leost M, Damiens E, Marie D, Marko D, Niederberger E, Tang W, Eisenbrand G, Meijer L (1999) Indirubin, the active constituent of a Chinese antileukaemia medicine, inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat. Cell Biol 1, 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.