Abstract

Objective:

This study evaluates the efficacy of passive ultrasonic irrigation (PUI) in removing root canal filling material from endodontically treated teeth after using one of two reciprocating systems, Reciproc (VDW, Munich, Germany) or WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), or one nickel-titanium (NiTi) rotary system, ProTaper Universal Retreatment (Dentsply Maillefer).

Methods:

One hundred and twenty straight root canals of extracted human maxillary incisors were instrumented and then obturated. The specimens were divided into six groups (n=20) as follows: Group R, Reciproc R25 instrument without PUI; Group W, WaveOne Primary instrument without PUI; Group PT, ProTaper Universal Retreatment system without PUI; Group R-PUI, Reciproc R25 with PUI; Group W-PUI, WaveOne Primary with PUI and Group PT-PUI, ProTaper Universal Retreatment system with PUI. After removing the filling material, the teeth were cleaved longitudinally and photographed. The total canal space and remaining material were quantified with the aid of an imaging software tool. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to identify significant differences between the groups.

Results:

No statistically significant differences (P>0.05) in residual filling material were observed between the groups.

Conclusion:

The use of PUI did not improve the removal of filling material from the root canals, regardless of the previously used instrumentation system.

Keywords: Nickel-titanium files, passive ultrasonic irrigation, reciprocating motion, retreatment, root canal therapy

HIGHLIGHTS.

It has been suggested that PUI can play an important supplementary role in cleaning the root canal system.

To date, there are few reports comparing reciprocating and rotary systems, with or without PUI and no solvent, regarding their effectiveness in removing root canal filling material.

Filling material was not completely removed by any of the filling removal techniques, all of which exhibited similar performance. Therefore, PUI did not increase the removal of filling material, regardless of the instrumentation system used previously.

INTRODUCTION

Persistent or secondary intraradicular infection is a major cause of endodontic failure, and nonsurgical retreatment is indicated in these cases (1-3). Effective removal of filling material from the root canal system is essential to ensure a successful outcome of the retreatment procedure (4). Performing this procedure effectively has an important clinical impact because it ensures that the instruments and irrigating solutions used during retreatment can reach the entire root canal system, thus promoting better cleaning and disinfection (5).

Several methods are available for removing root canal filling material, including manual files, rotary and reciprocating instruments and sonic or ultrasonic irrigation (6-11). However, all retreatment techniques have been found to leave some residual gutta-percha and sealer on canal walls after re-instrumentation (12).

One instrumentation system specifically developed for this purpose is the ProTaper Universal Retreatment system (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), consisting of instruments D1 (30/.09), D2 (25/.08) and D3 (20/.07) (8, 13).

A reciprocating motion approach was introduced for instrumentation using nickel-titanium instruments fabricated from M-Wire alloy; these are considered to be more resistant than conventional nickel-titanium (NiTi) alloys (14, 15). Two systems incorporating this technology are currently available on the market: Reciproc (VDW, Munich, Germany) and WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer). Both systems can be used with a 25/.08 instrument. The same technique recommended for endodontic treatment with these systems has been applied for retreatment purposes (9, 16, 17). During retreatment, the instruments are used with an in-and-out motion combined with a brushing action against the lateral walls of the canal to remove any residual filling material (16, 18).

Passive ultrasonic irrigation is defined as a small file or smooth wire oscillating freely in the root canal to induce powerful acoustic microstreaming. It has been suggested that PUI can play an important supplementary role in cleaning the root canal system (11). Different methods using PUI to complement the removal of filling material from the root canal system have previously been tested. Fruchi et al. (18) compared the effectiveness of reciprocating systems combined with PUI in removing filling material from curved canals, using xylene as a solvent, whereas Cavenago et al. (19) conducted a similar experiment, further comparing the filling removal effectiveness of reciprocating systems in curved canals using xylene alone and then with or without PUI combined with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl). To date, few reports have compared the effectiveness of reciprocating and rotary systems, with or without PUI or solvent, in removing root canal filling material (20).

Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare the efficacy of PUI for the removal of root canal filling material after using the WaveOne, Reciproc or ProTaper Universal Retreatment systems. The null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference between the systems used for removing filling material with or without PUI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection and specimen preparation

After approval by the institutional research ethics committee (protocol no. 2015/1.079.570), 120 extracted maxillary incisors with fully formed roots, single straight canals with apical patency, angles of curvature of less than 5° (as confirmed radiographically) and no calcification were selected for this study. Curvature angles were evaluated according to the Schneider method (21). The teeth were stored in a 0.1% thymol solution until use. The sample size calculation, based on a type I error of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, indicated an ideal sample size of 16 specimens in each group. Therefore, 20 specimens were used to ensure the reliability of the results.

The teeth were decoronated with a diamond disc (Brasseler USA, Savannah, GA) to obtain a standardised root length of 16 mm. After locating the canal orifice, a size 10 K-file was introduced into the canal until it became visible at the apical foramen with a dental operating microscope (DOM; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) under 12.5X magnification. The working length (WL) was established by subtracting 1 mm from this measurement.

Root canal preparation

All root canals were instrumented by the same operator using the NiTi ProTaper Rotary system (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). The cervical and middle thirds of the canals were enlarged using ProTaper SX and S1 rotary files. Files S1 and S2 were used to instrument the middle and apical thirds until slight resistance was encountered. The canals were finished using instruments F1, F2, F3 and F4 at the WL. All instruments were applied at a speed of 300 rpm and a torque of 3 N as recommended by the manufacturer. The root canals were irrigated with 2.5% NaOCl solution at each instrument change to a total of 25 mL per specimen. After completion of root canal instrumentation, the canals were irrigated with 5 mL 17% ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 3 minutes to remove the smear layer, and a final irrigation was performed with 5 mL 2.5% NaOCl solution.

The root canals were dried with paper points and then filled with gutta-percha M cones (Dentsply Maillefer) and AH Plus Sealer (Dentsply DeTrey, Konstanz, Germany) using the continuous wave of condensation technique with a Touch’n Heat device (SybronEndo, Orange, CA). The gutta-percha cones were previously calibrated with a calibrating ruler (Dentsply Maillefer). In a second stage, the middle and cervical thirds of the canals were filled with plasticised gutta-percha using the Obtura II (SybronEndo) system. Buccolingual and mesiodistal radiographs were acquired with a digital CDR Elite Sensor (Schick Technologies, Long Island City, NY) to assess the filling quality. Specimens showing voids within the fillings were discarded. The coronal access cavities were sealed using a temporary filling material (Cavit-G; 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany). All the specimens were stored at 37 ºC and 100% humidity for 30 days to allow the sealer to set fully.

Filling removal technique

The 120 teeth were randomly divided into 6 groups of 20 using a computerised algorithm (http:// www.random.org). The groups were formed according to the system used for filling removal and according to the irrigation method, with or without PUI, as follows: Group R: R25 instrument of the Reciproc system without PUI; Group W: Primary instrument of the WaveOne system without PUI; Group PT: NiTi rotary instrument of the ProTaper Universal Retreatment system without PUI; Group R-PUI: R25 instrument of the Reciproc system with PUI; Group W-PUI: Primary instrument of the WaveOne system with PUI and Group PT-PUI: NiTi rotary instrument of the ProTaper Universal Retreatment system with PUI.

In group R, the R25 instrument of the Reciproc system was used in the VDW Silver motor ‘RECIPROC ALL’ mode. In group W, the Primary instrument of the WaveOne system was used with the same motor in the ‘WAVEONE ALL’ mode. Both instruments were moved towards the apex using an in-and-out motion, with an amplitude of approximately 3 mm, combined with a brushing action against the lateral walls. The instrument was removed from the canal and cleaned with sterile gauze after three strokes. This procedure was repeated until the instrument reached its WL. The D1, D2 and D3 files of the ProTaper Universal Retreatment system were used sequentially, in an in-and-out motion towards the apex, until the WL was reached. All the instruments were used with a VDW Silver motor at constant speeds of 500 rpm for D1 and of 400 rpm for D2 and D3, with a torque of 3 N. The same operator, who was experienced in all the filling removal techniques tested, performed all the procedures. Both the reciprocating and rotary instruments were used in only one root canal and were then discarded. Irrigation during filling removal was performed using a total of 25 mL 2.5% NaOCl solution per tooth. Irrigation with 5 mL 17% EDTA was performed for 3 minutes to remove the smear layer in each root canal, followed by a final irrigation with 5 mL 2.5% NaOCl introduced with a 30-gauge-needle (tip size 25) 2 mm below the WL.

In the other three groups, PUI was performed after mechanical removal of the filling. PUI was conducted for one minute, in three cycles of 20 s, with an intracanal stainless steel ultrasonic tip (#0.20, taper 0.00) (Irrisafe; Acteon, Merignac, France) at 1 mm below the WL, combined with 17% EDTA solution; an up-and-down motion was employed. The ultrasonic device used was the MTS Ultrasonic Obtura Spartan system (Obtura Spartan Endodontics, Algonquin, IL), set to operate at 30%. After one minute of activation (3 x 20 s), the solution was replenished and remained two minutes inside the root canal, thus maintaining the same EDTA volume (5 mL) and total irrigation time (three minutes) for all groups. A final irrigation with 5 mL 2.5% NaOCl was performed for each specimen, this time without ultrasonic activation, at 2 mm below the WL.

The filling removal procedure was considered complete when no filling material could be seen to adhere to the instrument or to the canal walls, as confirmed by the DOM under 12.5X magnification. No instrument fractures were recorded.

Filling removal assessment

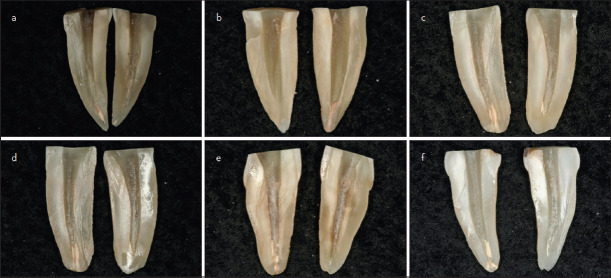

After grooving the buccal and lingual aspects of the teeth with a diamond disc (Brasseler USA), the teeth were cleaved with a spatula. Both root halves were photographed with a digital camera (Sony PC120; Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) coupled to the DOM under 5X magnification (Figure 1). The residual filling material was first assessed by loading the images into imaging software (Image Tool for Windows v. 3.00; University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, USA) and then measuring the area of the remaining filling material relative to the total root canal area. The filling remnants were traced, computed and expressed in square pixels. The mean percentage values relative to the total canal area were then compared.

Figure 1.

a-f. Images representing the cleaning results obtained in each group. (a) WaveOne with PUI, (b) WaveOne without PUI, (c) Reciproc with PUI, (d) Reciproc without PUI, € ProTaper with PUI and, (f) ProTaper without PUI

PUI: passive ultrasonic irrigation

The mean filling material percentage areas were analysed by the Kruskal-Wallis and The Mann-Whitney tests. The calculations were performed with the SAS (Statistical Analysis System) system, release 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA).

RESULTS

Remnants of root canal filling material were observed in all the samples, regardless of the filling removal technique. The mean areas of residual filling material were 4.30% in group R, 2.98% in group W, 3.14% in group PT, 3.28% in group R-PUI, 2.96% in group W-PUI and 3.07% in group PT-PUI (Table 1). No statistically significant difference (P>0.05) was observed between the groups.

TABLE 1.

Mean percentage areas (standard deviations) of residual filling material on canal walls after the application of different filling removal methods

| Group | Mean (Standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Reciproc | 4.30±2.56 |

| WaveOne | 2.98±1.87 |

| ProTaper retreatment | 3.14±1.71 |

| Reciproc+PUI | 3.28±0.60 |

| WaveOne+PUI | 2.96±0.70 |

| ProTaper retreatment+PUI | 3.07±0.92 |

PUI: Passive ultrasonic irrigation, Non-significant difference at the 5% level

DISCUSSION

The success of root canal retreatment is directly related to the maximum removal of filling material. The purpose of the removal technique is to clear areas where pulp tissue or bacteria could remain and cause the previous treatment to fail (22).

Although root canal anatomy varies widely, single-rooted human teeth with canals with round cross-sections were used in this study because such teeth are comparatively easier to standardise for experimentation purposes (16, 23). Moreover, the crowns of the teeth were removed to prevent the influence of anatomical structures on root canal access and to increase the similarity of the canal sizes.

The amount of residual filling material was assessed by sectioning the roots longitudinally into separate halves and photographing the specimens (13, 24). Recent studies have used this methodology to assess the amount of remaining gutta-percha and sealer (9, 16, 23, 25). The ratio of the mean area of the remnant material to the total area of the canal, calculated by a computer program, provides a reliable estimate of the filling material remaining in the root canal system.

In this study, the amount of residual filling material was verified using a DOM under 12.5X magnification, in accordance with a previous study which stressed the importance of using an operating microscope in endodontic retreatment procedures (26). Furthermore, the instruments used to remove the root canal filling material were reapplied until the material could no longer be detected by the operator under this magnification.

There is no consensus regarding the most efficient instrument type for retreatment procedures. Some studies indicate that hand files can remove more filling material, whereas other studies predicate that NiTi rotary systems are more effective; still other studies have found no difference between the methods (6, 7, 17, 23, 27, 28). Although a previous study has shown a reciprocating system to be more effective than rotary files for the removal of root canal filling material, a recent study found no difference between these systems; this finding is in agreement with our results (9, 25).

The D3 instrument (tip size 20) of the ProTaper Universal Retreatment system is the final instrument recommended by the manufacturer, whereas the R25 instrument (tip size 25) of the Reciproc system and the Primary instrument (tip size 25) of the WaveOne system were selected because the tips of these reciprocating instruments are the closest equivalents to the tip of the D3 instrument. Instrumentation up to the WL using larger instruments than those used during initial treatment is required to achieve enhanced cleansing (29).

The presence of root canal filling material after instrumentation with both rotary and reciprocating instruments has also been reported in the literature (9, 16, 18). Thus, irrigation as a complementary procedure should be emphasised to achieve complete removal of root canal filling materials.

Passive ultrasonic irrigation can aid in the removal of residual material by activating the irrigating solution, thereby improving its cleaning efficiency, and by allowing the solution to reach irregularities which may be inaccessible to mechanical action (11). Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of PUI in removing root canal filling material from curved and flattened canals with or without solvent (18-20). Because it can be more difficult to reach all canal walls mechanically in curved and oval canals, the importance of irrigation, including PUI, is heightened in such cases. However, the results of this study showed that PUI, specifically, had no influence on the removal of root canal filling material from maxillary incisors. This may be related to the anatomy of these teeth, which have wide, straight root canals with round cross-sections (30). Observation of this specific anatomy under magnification permitted the operator to inspect the root canal space and remove most of the filling materials with rotary or reciprocating instruments alone.

In the present study, the retreatment procedures were performed without the use of solvent as an adjunct to remove gutta-percha/sealer material. The use of solvent is controversial in the related literature. Cavenago et al. (19) found xylene to be helpful in removing filling material, whereas other studies showed that solvent did not increase gutta-percha/sealer removal from curved or straight canals (8, 18). Recent studies have evaluated different retreatment systems without solvent to prevent the interference of a thin layer of gutta-percha which forms and adheres to the root canal walls (16, 20, 31).

Grischke et al. (10) found that PUI can remove AH Plus root canal sealer from the root canal surface of straight canals with simulated irregularities better than syringe irrigation. The presence of these irregularities may increase the influence of PUI on sealer removal. This study, however, considered the removal of both sealer and gutta-percha materials and used specimens containing canals without visible anatomical irregularities.

De Mello Junior et al. (26) achieved better results when an ultrasonic tip was used as an adjunct to remove gutta-percha/sealer from the root canal space. However, in their study, the presence of residual filling material was evaluated by radiography, and a DOM was used only in the group in which ultrasonic tips were used. In the present study, a DOM was used to evaluate the presence of root canal filling material in all groups, and both rotary and reciprocating instruments were used until no material could be seen inside the root canal space under magnification. It can be concluded that a microscopic evaluation of the remnants, followed by proper procedures for their removal, is an effective way to maintain low levels of residual filling material in straight, short canals with round cross-sections. Further studies should evaluate the influence of PUI on complex anatomies.

CONCLUSION

Passive ultrasonic irrigation did not increase the removal of filling material in straight root canals regardless of the instrumentation system used, confirming the null hypothesis of this study. The filling material was not completely removed by any of the filling removal techniques.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from institutional research ethics committee. (Decision No: 2015/1.079.570).

Informed Consent: N/A.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship Contributions: Concept - C.E.S.B.; Design - M.A.R.; Supervision - M.S.C.; Resource - A.M.V.; Materials - A.S.M.; Data Collection and/or Processing - A.S.K.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - V.O.A.; Literature Search - R.S.C.; Writing - C.E.S.B., M.A.R.; Critical Reviews - C.E.S.B., M.S.C.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siqueira JF., Jr Aetiology of root canal treatment failure:why well-treated teeth can fail. Int Endod J. 2001;34(1):1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças Clinical implications and microbiology of bacterial persistence after treatment procedures. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torabinejad M, Corr R, Handysides R, Shabahang S. Outcomes of nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic surgery:a systematic review. J Endod. 2009;35(7):930–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollo A, Botti G, Prinicipi Goldoni N, Randellini E, Paragliola R, et al. Efficacy of two Ni-Ti systems and hand files for removing gutta-percha from root canals. Int Endod J. 2012;45(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorni FG, Gagliani MM. The outcome of endodontic retreatment:a 2-yr follow-up. J Endod. 2004;30(1):1–4. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenoul G, Meless GD, Pérez F. The efficacy of R-Endo rotary NiTi and stainless-steel hand instruments to remove gutta-percha and Resilon. Int Endod J. 2010;43(2):135–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammad M, Qualtrough A, Silikas N. Three-dimensional evaluation of effectiveness of hand and rotary instrumentation for retreatment of canals filled with different materials. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1370–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi CM, Cunha RS, de Martin AS, Fontana CE, Silveira CF, da Silveira Bueno CE. In vitro evaluation of the effectiveness of ProTaper universal rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal with or without a solvent. J Endod. 2009;35(11):1580–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuolo AS, Mello JE Jr, Cunha RS, Zuolo ML, Bueno CE. Efficacy of reciprocating and rotary techniques for removing filling material during root canal retreatment. Int Endod J. 2013;46(10):947–53. doi: 10.1111/iej.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grischke J, Müller-Heine A, Hülsmann M. The effect of four different irrigation systems in the removal of a root canal sealer. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18(7):1845–51. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Sluis LW, Versluis M, Wu MK, Wesselink PR. Passive ultrasonic irrigation of the root canal:a review of the literature. Int Endod J. 2007;40(6):415–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wennberg A, Orstavik D. Evaluation of alternatives to chloroform in endodontic practice. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1989;5(5):234–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1989.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tasdemir T, Yildirim T, Celik D. Comparative study of removal of current endodontic fillings. J Endod. 2008;34(3):326–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yared G. Canal preparation using only one Ni-Ti rotary instrument:preliminary observations. Int Endod J. 2008;41(4):339–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HC, Kwak SW, Cheung GS, Ko DH, Chung SM, Lee W. Cyclic fatigue and torsional resistance of two new nickel-titanium instruments used in reciprocation motion:Reciproc versus WaveOne. J Endod. 2012;38(4):541–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rios Mde A, Villela AM, Cunha RS, Velasco RC, De Martin AS, Kato AS, et al. Efficacy of 2 reciprocating systems compared with a rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal. J Endod. 2014;40(4):543–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rödig T, Reicherts P, Konietschke F, Dullin C, Hahn W, Hülsmann M. Efficacy of reciprocating and rotary NiTi instruments for retreatment of curved root canals assessed by micro-CT. Int Endod J. 2014;47(10):942–8. doi: 10.1111/iej.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fruchi Lde C, Ordinola-Zapata R, Cavenago BC, Hungaro Duarte MA, Bueno CE, De Martin AS. Efficacy of reciprocating instruments for removing filling material in curved canals obturated with a single-cone technique:a micro-computed tomographic analysis. J Endod. 2014;40(7):1000–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavenago BC, Ordinola-Zapata R, Duarte MA, del Carpio-Perochena AE, Villas-Bôas MH, Marciano MA, et al. Efficacy of xylene and passive ultrasonic irrigation on remaining root filling material during retreatment of anatomically complex teeth. Int Endod J. 2014;47(11):1078–83. doi: 10.1111/iej.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardes RA, Duarte MA, Vivan RR, Alcalde MP, Vasconcelos BC, Bramante CM. Comparison of three retreatment techniques with ultrasonic activation in flattened canals using micro-computed tomography and scanning electron microscopy. Int Endod J. 2015;49(9):890–7. doi: 10.1111/iej.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider SW. A comparison of canal preparations in straight and curved root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;32(2):271–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(71)90230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saad AY, Al-Hadlaq SM, Al-Katheeri NH. Efficacy of two rotary NiTi instruments in the removal of Gutta-Percha during root canal retreatment. J Endod. 2007;33(1):38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colaco AS, Pai VA. Comparative evaluation of the efficiency of manual and rotary gutta-percha removal techniques. J Endod. 2015;41(11):1871–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giuliani V, Cocchetti R, Pagavino G. Efficacy of ProTaper universal retreatment files in removing filling materials during root canal retreatment. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1381–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souza PF, Oliveira Goncalves LC, Franco Marques AA, Sponchiado EC, Junior, Roberti Garcia Lda F, de Carvalho FM. Root canal retreatment using reciprocating and continuous rotary nickel-titanium instruments. Eur J Dent. 2015;9(2):234–9. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.156834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Mello JE, Junior, Cunha RS, Bueno CE, Zuolo ML. Retreatment efficacy of gutta-percha removal using a clinical microscope and ultrasonic instruments:part I--an ex vivo study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(1):e59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zmener O, Pameijer CH, Banegas G. Retreatment efficacy of hand versus automated instrumentation in oval-shaped root canals:an ex vivo study. Int Endod J. 2006;39(7):521–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schirrmeister JF, Wrbas KT, Meyer KM, Altenburger MJ, Hellwig E. Efficacy of different rotary instruments for gutta-percha removal in root canal retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32(5):469–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bramante CM, Fidelis NS, Assumpção TS, Bernardineli N, Garcia RB, Bramante AS, et al. Heat release, time required, and cleaning ability of MTwo R and ProTaper universal retreatment systems in the removal of filling material. J Endod. 2010;36(11):1870–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vertucci FJ, Gegauff A. Root canal morphology of the maxillary first premolar. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;99(2):194–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu LS, Ling JQ, Wei X, Huang XY. Efficacy of ProTaper Universal rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal from root canals. Int Endod J. 2008;41(4):288–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]