Highlights

-

•

A COVID-19 infection risk model from multiple exposure pathways was developed.

-

•

The effectiveness of personal protective equipment in a health-care worker was evaluated.

-

•

Droplet spraying was the major infection pathway, contributing to 60%–86% of cases.

-

•

Hand contact via contaminated surfaces contributed to 9%–32% of cases of infection.

-

•

Personal protective equipment decreased the infection risk by 63%–>99.9%.

Keywords: COVID-19, Health-care, Infection, Multiple pathways, Risk assessment, SARS-CoV-2

Abstract

We assessed the risk of COVID-19 infection in a healthcare worker (HCW) from multiple pathways of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in a health-care setting of short distance of 0.6 m between the HCW and a patient while caring, and evaluated the effectiveness of a face mask and a face shield using a model that combined previous infection-risk models. The multiple pathways of exposure included hand contact via contaminated surfaces and an HCW’s fingers with droplets, droplet spray, and inhalation of inspirable and respirable particles. We assumed a scenario of medium contact time (MCT) and long contact time (LCT) over 1 day of care by an HCW. SARS-CoV-2 in the particles emitted by coughing, breathing, and vocalization (only in the LCT scenario) by the patient were considered. The contribution of the risk of infection of an HCW by SARS-CoV-2 from each pathway to the sum of the risks from all pathways depended on virus concentration in the saliva of the patient. At a virus concentration in the saliva of 101–105 PFU mL−1 concentration in the MCT scenario and 101–104 PFU mL−1 concentration in the LCT scenario, droplet spraying was the major pathway (60%–86%) of infection, followed by hand contact via contaminated surfaces (9%–32%). At a high virus concentration in the saliva (106–108 PFU mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 105–108 PFU mL−1 in the LCT scenario), hand contact via contaminated surfaces was the main contributor (41%–83%) to infection. The contribution of inhalation of inspirable particles was 4%–10% in all assumed cases. The contribution of inhalation of respirable particles increased as the virus concentration in the saliva increased, and reached 5%–27% at the high saliva concentration (107 and 108 PFU mL−1) in the assumed scenarios using higher dose–response function parameter (0.246) and comparable to other pathways, although these were worst and rare cases. Regarding the effectiveness of nonpharmaceutical interventions, the relative risk (RR) of an overall risk for an HCW with an intervention vs. an HCW without intervention was 0.36–0.37, 0.02–0.03, and <4.0 × 10−4 for a face mask, a face shield, and a face mask plus shield, respectively, in the likely median virus concentration in the saliva (102–104 PFU mL−1), suggesting that personal protective equipment decreased the infection risk by 63%–>99.9%. In addition, the RR for a face mask worn by the patient, and a face mask worn by the patient plus increase of air change rate from 2 h−1 to 6 h−1 was <1.0 × 10−4 and <5.0 × 10−5, respectively in the same virus concentration in the saliva. Therefore, by modeling multiple pathways of exposure, the contribution of the infection risk from each pathway and the effectiveness of nonpharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19 were indicated quantitatively, and the importance of the use of a face mask and shield was confirmed.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province of China, in December 2019 (Zhu et al., 2020). The SARS-CoV-2 epidemic rapidly spread worldwide (Chen et al., 2020a) and the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020a). COVID-19 poses a great public health, clinical, economical, and societal burden worldwide.

Human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs mainly through close contact, similar to other respiratory viruses, such as influenza or human coronaviruses (Cheng et al., 2020, Lai et al., 2020, Sungnak et al., 2020, WHO, 2020b). Respiratory viruses can be transmitted via direct and indirect contact (via fomites), and through the air via respiratory droplets and/or airborne particles (Nicas and Sun, 2006, Nicas and Jones, 2009, Tellier et al., 2019). Therefore, the possible exposure pathways for infection by SARS-CoV-2 are: hand contact with virus-contaminated surfaces (fomites) and subsequent handcontact with the conjunctiva, nostrils, or lips; inhalation of viruses carried in airborne particles exhaled by coughing or vocalization that have an aerodynamic diameter (DA) < 10 μm (respirable particles, referred to as droplet nuclei or aerosols); inhalation of viruses carried in airborne particles exhaled by coughing or vocalization that exhibit 10 μm < DA < 100 μm (inspirable particles, referred to as respiratory droplets); and droplet spraying, which is the direct projection of viruses carried in particles exhaled by coughing or vocalization (generally, DA > 100 μm) onto facial target membranes. Respirable particles deposit throughout the respiratory tract, including the alveolar region, whereas inspirable particles deposit in the head airways and tracheobronchial regions only (Oberdörster et al., 2005, USEPA, 2019).

In pathway of hand contact, SARS-CoV-2 remains in the contaminated surfaces for prolonged periods (van Doremalen et al., 2020). In pathway of inhalation of respirable particles, airborne particles carrying SARS-CoV-2 remain suspended in the air for prolonged periods (van Doremalen et al., 2020, Fears et al., 2020), thus allowing infection of susceptible individuals located at a greater distance from the site of expulsion (Morawska and Cao, 2020). Pathways of inhalation of inspirable particles and droplet spray require close contact between infected and susceptible individuals, usually within 1 m of the site of expulsion (WHO, 2020b). According to current evidence, SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted between people through respiratory droplets and contact routes (Burke et al., 2020, Chan et al., 2020, Huang et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020a). However, the possibility of the contribution of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 caused by pathway of inhalation of respirable particles has been suggested and discussed (Anderson et al., 2020, Buonanno et al., 2020, Godri Pollitt et al., 2020, Morawska and Cao, 2020, Stadnytskyi et al., 2020).

In the appropriate control of human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the relative contributions of the pathways of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 detailed above to the risk of COVID-19 have to be quantified, to determine the potential efficacy of interventions using protective equipment, such as partitions, masks, or gloves; human activities or behaviors, such as hand washing or social distancing; environmental cleanup; or ventilation. Adequate human behaviors play a significant role in the prevention of the spread of COVID-19 (Azuma et al., 2020).

The objective of this study was to estimate the relative contribution of each of the exposure pathways to SARS-CoV-2 to the risk of COVID-19. Healthcare workers (HCWs) on the front lines of the care against COVID-19 have an increased risk of COVID-19 compared with individuals in the general community, and HCWs with inadequate access to personal protective equipment (PPE) have an even higher risk (Cheng et al., 2020, Nguyen et al., 2020). Studies have reported that the COVID-19 infection rate among HCWs ranges from 3.5% to 20% of the infected population (Ali et al., 2020, Ha, 2020). Major factors for infection among HCWs include the lack of understanding of the disease and inadequate use and unavailability of PPE (Ali et al., 2020). We set the environmental exposure scenario for a HCW working at a hospital room of a patient with COVID-19. In addition, we examined the effectiveness of various forms of PPE as interventions to decrease the risk of COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Exposure scenario

We assumed that a symptomatic patient was admitted to a hospital room and that, during admission, the patient emitted droplets continuously via coughing and vocalization (in one scenario described below) and breathing. An HCW was assumed to visit the patient’s room periodically and care for the patient. The infection risk of the HCW during an 8 h work shift over 1 day was calculated. We assumed two scenarios of contacting time, namely, a medium contact time (MCT) and a long contact (LCT) scenario. In the MCT scenario, we assumed that the HCW visited the patient room 20 times in 1 day, and each care time was 1 min, based on the survey reported by Cohen et al. (2012) (median time spent in patient’s rooms during each entry of 2 and 3 min, average visiting of 2.8 and 4.5 different patients/hour, and visits of 45% and 17%, by nursing staffs and medical staffs, respectively; median room entries of 5.5 persons/hour). Therefore, the total contact time was 20 min. During the contact time, the HCW did not have a conversation with the patient. In the LCT scenario, the HCW visited the patient room 6 times in 1 day, and each care time was 10 min; thus, the total contact time was 60 min. Moreover, in this scenario, the HCW had a conversation with the patient for 30 min during the contact time. These durations of the contact and conversation were based on the actual infection case of a nurse (Kawada et al., 2020).

2.2. Input parameters of the exposure model

2.2.1. Hospital room environment

We assumed that a patient was admitted to a general single-patient room, rather than a bed in an infectious disease ward, because of the limited number of these beds in case of an acute increase in patients. The room volume was set to 22.7 m3, which is the product of the area per bed in a general hospital (8.7 m2; MHLW, 2009) and the building ceiling height (2.61 m; JBOMA, 2013). The air change rate in the hospital room was set to two per hour (HEAJ, 2013), which is the worst case assumption, considering only the introduction of a minimum volume of outdoor air in a general patient room (without considering circulated air). Infection from hand contact occurs via surfaces in the room. We assumed that the surfaces accessible by the HCW included textile (such as bed sheets) and nontextile (such as a desk) materials around the patient in the room, with a surface area of 9000 and 1000 cm2, respectively (Nicas and Jones, 2009).

2.2.2. Patient with COVID-19 infection

The cough frequency of a COVID-19 infectious patient was set to 30 h−1 (one cough per 2 min), for simplicity, based on the cough frequency of participants infected by a seasonal human coronavirus [mean, 17 (s.d. = 30) coughs during 30 min; Leung et al., 2020]. The saliva volume per one cough was set to 0.044 mL, as calculated using the data pertaining to the number of droplets with a diameter above 1 μm recorded during coughing by Loudon and Roberts (1967) (Nicas et al., 2005, Nicas and Sun, 2006). Moreover, we considered the contribution of particles with a diameter < 1 μm (Morawska et al., 2009). Morawska et al. (2009) reported the concentration of an aerosol with a diameter ranging from 0.3 to 20 μm for specific size distribution modes during expiratory activities, including breathing, vocalization and repeated coughing. We calculated the ratio of the number of particles expelled during repeated coughing with diameter < 1 μm (mode of 0.8 μm) to the sum of that of particles with a diameter > 1 μm (mode of 1.8, 3.5, and 5.5 μm). Subsequently, using this ratio, we extrapolated the number of cough particles with diameter < 1 μm from the data of the total number of particles with diameter from 1 to 20 μm, as calculated based on Loudon and Roberts (1967). The addition of the extrapolated volume of particles < 1 μm to the volume of droplets with a diameter > 1 μm expelled during coughing reported by Loudon and Roberts (1967) yielded a volume of particles from one cough of 0.044 mL, which was used as the input value.

In the LCT scenario, the patient had a conversation with the HCW for 30 min. During this time, the saliva volume per 30 s of talking was set to 0.050 mL, which was calculated using the data of the number of droplets with a diameter > 1 μm during talking reported by Loudon and Roberts (1967) and the concentration of the aerosol emitted during the voiced counting of particles with a diameter < 1 μm (Morawska et al., 2009), as described below. The data of Loudon and Roberts (1967) were the number of droplets produced during counting loudly from one to 100 twice by 3 subjects (total, counting of 600). Therefore, assuming a speed of counting of 1 count per 1 s, one twentieth (30/600) of the total number of particles was assumed as the number of droplets produced during 30 s of talking. In addition, particles emitted during voiced counting with a diameter < 1 μm (Morawska et al., 2009) were also added using the method mentioned above. For simplicity, it was assumed that 30 s of talking and a cough occurred at the same time in close contact. In addition, during the 30 coughs included in the LCT scenario over 60 min, a total 15 min of vocalization was performed by the patient, which corresponded to 30 min of conversation in the LCT scenario by adding the same time of vocalization (15 min) by the HCW.

The SARS-CoV-2 concentration in the saliva was set from 101 to 108 PFU mL−1 (henceforth, PFU mL−1 will be referred to as mL−1) based on the data of patients with COVID-19 infection (To et al., 2020a, To et al., 2020b, Wyllie et al., 2020). The exhalation rate was set to 0.37 m3 h−1, which was estimated as the mean inhalation rate for Japanese males and females while sleeping and resting in a recumbent position (NIRS, 1998), and was used for exposure factor derivation of the mean inhalation rate among Japanese males and females (AIST, 2007).

2.2.3. HCW caring for the patient

The inhalation rate of the HCW was set to 0.91 m3 h−1, which was the estimated rate during standing activity (NIRS, 1998), and was used for exposure factor derivation of the mean inhalation rate of Japanese males and females (AIST, 2007). The distance between the HCW and the patient was set to 0.6 m (Nicas and Jones, 2009), which corresponded to the distance when the HCW carried out caring duties (close contact). The close contact duration was 30 s for each caring time of 1 min in the MCT scenario and 5 min (conversation) for each caring time of 10 min in the LCT scenario.

2.3. Dose–response assessment

To the best of our knowledge, a dose–response relationship for SARS-CoV-2 as a cause of COVID-19 has not been reported. One recent study showed that transgenic (hACE2) mice became infected after timed aerosol exposure to SARS-CoV-2. However, key methodological details (e.g., particle size and quantification of actual aerosol dose) were missing from the report of that study (Bao et al., 2020). Therefore, we employed the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) dose–response model (Mitchell and Weir, 2020) as a surrogate of the SARS-CoV-2 response.

SARS-CoV-2 has many similarities to SARS-CoV. Both viruses are classified as a β-coronavirus, which is an enveloped non-segmented positive-sense RNA virus (subgenus Sarbecovirus, Orthocoronavirinae subfamily) (Guo et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is most closely related to SARS-CoV, indicating that the genomic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV have extremely high homology at the nucleotide level, as they share about 80% of the gene sequence (Zhou et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 uses the same entry-cell receptor, i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), to infect humans, as dose SARS-CoV, and mainly spreads through the respiratory tract. ACE2 regulates both the cross-species and human-to-human transmission of these viruses (Ceccarelli et al., 2020, Guo et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020). The clinical presentation and pathology of COVID-19 greatly resemble those of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by SARS-CoV, including fever, chills, cough, shortness of breath, headache, generalized myalgia, malaise, drowsy, hemoptysis, nausea, confusion, dyspnea, pneumonia (Meo et al., 2020, Xie and Chen, 2020), and intravascular coagulopathy (Giannisa et al., 2020). The mean incubation period (i.e., the period between infection and the onset of symptoms) is about 5 days for SARS-CoV (Hui, 2017) and SARS-CoV-2 (Lauer et al., 2020). Both viruses are transmitted from human-to-human mainly through close contact, respiratory droplets, fomites, and contaminated surfaces (Ceccarelli et al., 2020, van Doremalen et al., 2020). Furthermore, the basic reproduction number (usually denoted by R0) is a very important threshold quantity associated with viral transmissibility. In the early epidemic in China, an R0 of 2–3.6 was reported for SARS-CoV-2 (Ferretti et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020b, Zhao et al., 2020), which was similar to the R0 of 2–5 reported for SARS-CoV in China (Bauch et al., 2005, Chen, 2020, Lipsitch et al., 2003, Wallinga and Teunis, 2004).

Based on these evidences, we assumed that the SARS dose–response model is the best available model to use as a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2 in the present study. Several dose–response studies were examined to determine a recommended dose–response model for SARS (De Albuquerque et al., 2006, DeDiego et al., 2008, Watanabe et al., 2010). The recommended dose–response model for SARS follows the exponential dose–response relationship for exposure dose expressed in PFU and the probability of a response based on the end point of death in mice (De Albuquerque et al., 2006, DeDiego et al., 2008). For translating this animal dose–response relationship into a human dose–response relationship, a generally accepted assumption that a death end point for an animal model may be used for examining the human risk of infection was applied (Haas et al., 2014). The general equation used for the exponential model was as follows:

| (1) |

where R is the risk (probability) of infection, k is the optimized dose–response function parameter (PFU−1), and d is the dose (PFU). We used the median value of 0.00246 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.00135–0.00459] with a normal distribution reported by Mitchell and Weir (2020) as the k value.

The cumulative risk of the morbidity across multiple exposure times was calculated using Eq. (2) (Haas et al., 2014), as follows:

| (2) |

where Rc is the cumulative risk at a given R and n is the cumulative number of the repeated exposure with R.

Mitchell and Weir (2020) provided the dose–response data pertaining to the upper respiratory tract. Therefore, considering the uncertainty in the dose–response data and our estimates of the infectivity of the respirable viral particles deposited in the lower respiratory tract, we assumed alternative ratios of 100:1 and 1:1 for the infectivity of viruses deposited in the lower respiratory tract vs. the upper respiratory tract, based on data on the influenza virus in humans (Alford et al., 1966, Couch et al., 1971, Couch and Kasel, 1983, Murphy et al., 1973). Recent findings on SARS-CoV-2 revealed that the ACE2 was expressed at the highest level in the nose, with decreased expression throughout the lower respiratory tract (approximately 4:1), paralleled by a striking gradient of SARS-CoV-2 infection in proximal (high) vs. distal (low) pulmonary epithelial cultures (Hou et al., 2020). In fact, the alternative ratio of 100:1 for the infectivity of the viruses deposited in the lower respiratory tract vs. the upper respiratory determined in our study may be an overestimation. However, we assumed the ratio of 100:1 for our estimation, as a conservative measure.

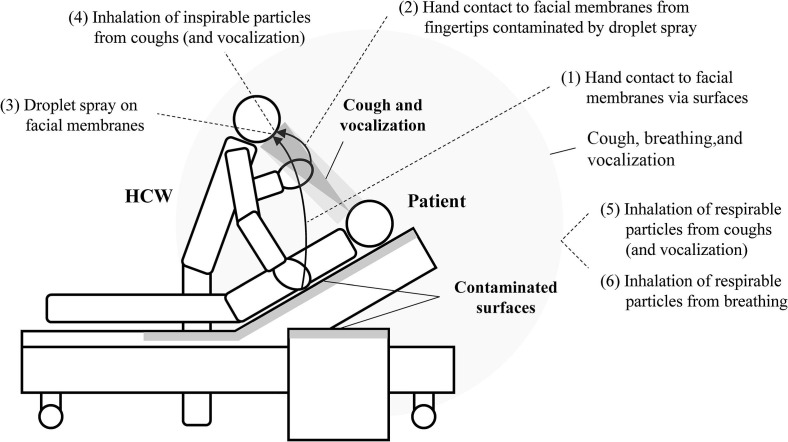

2.4. Exposure modeling

The exposure pathways considered in this study are shown in Fig. 1 . The pathways mentioned above were further subdivided into six pathways, as follows: (1) hand contact with facial membranes via surfaces, (2) hand contact with facial membranes from fingertips contaminated by droplet spray, (3) droplet spray on facial membranes, (4) inhalation of inspirable particles from cough (and vocalization), (5) inhalation of respirable particles from cough (and vocalization), (6) inhalation of respirable particles from breathing. Note that pathway (4) was short-range inhalation and pathways (5) and (6) were long-range inhalation. To do this, for pathways (1) to (5), we used the integrated model of infection risk in a health-care environment developed by Nicas and Sun (2006), with several modifications. This model was used to quantify the relative contribution of four exposure pathways to the influenza infection risk of a person attending to a bed-ridden family member ill with influenza (Nicas and Jones, 2009), thus we also referred the methodology and parameters in this article. Additionally, for pathways (2) to (4) which were close contact pathways, we referred a recent study by Chen et al. (2020b), which modeled the exposure via short range airborne and large droplet sub-routes during close contact and compared them. For pathway (6), we referred a model developed by Buonanno et al. (2020), which estimated airborne viral emission considering respiratory activity (breathing, speaking, whispering, etc.), respirator parameters (such as inhalation rate), and activity level. This model was applied to evaluate the number of people infected by an asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 subject in indoor microenvironments and to investigate the effectiveness of the virus containment measures. The calculation methods of infection risks for the considered exposure pathways are described in detail below.

Fig. 1.

Pathways of exposure considered in the scenarios of the present study.

2.4.1. Hand contact via surfaces and inhalation of respirable particles from cough and vocalization

Viruses emitted from a patient’s cough and vocalization are distributed the room’s air and various indoor surfaces and transferred to the target subject while being decreased by viral inactivation and ventilation. To simulate these dynamics and estimate the amount of virus present in this type of exposure, a Markov chain was used (Nicas and Sun, 2006, Nicas and Jones, 2009, King et al., 2015, Lei et al., 2017). In this model, eight states were assumed: 1, room air; 2, textile surfaces near the patient; 3, nontextile surfaces near the patient; 4, HCW’s hands; 5, HCW’s facial membranes; 6, HCW’s lower respiratory tract; 7, virus rendered noninfectious by environmental degradation; and 8, room exhaust air flow. Viruses were transferred from state i to j with first-order rate constants denoted by λ ij. The description and input values of λ ij are summarized in Table 1 and the detailed derivation is indicated in Table S1. Using λ ij, an 8 × 8 matrix of transfer probability, p ij, after a time step of Δt was calculated (Nicas and Sun, 2006). Subsequently, by multiplying the matrix of p ij n = t / Δt times, the transfer probability after time t, p ij (n), was calculated. A Δt of 1 × 10−4 min was used; thus, n was 10,000 in the case of 1 min, which was the time of care delivered by the HCW during one visit to the patient in the MCT scenario, as mentioned above. The calculation of p ij (n) was performed using the wxMaxima 19.01.2x open-source computer algebra system.

Table 1.

Transfer rate between states (min−1).

| Description | Input value | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| From state 1 (room air) | |||

| λ12 | Deposition rate of respirable particles on textile surfaces | 5.9 × 10−3 | Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ13 | Deposition rate of respirable particles on nontextile surfaces | 6.6 × 10−4 | Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ16 | Rate constant by inhalation by an HCW | 6.7 × 10−4 | AIST, 2007 |

| λ17 | Inactivation rate of SARS-CoV-2 in air | 1.1 × 10−2 | van Doremalen et al., 2020 |

| λ18 | Air change rate | 3.3 × 10−2 | HEAJ, 2013 |

| From state 2 (textile surfaces) | |||

| λ21 | Resuspension from textile surfaces | 0 | Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ24 | Transfer rate from textile surfaces to HCW’s hands | 2.8 × 10−6 | Bean et al., 1982, Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ27 | Inactivation rate of SARS-CoV-2 on textile surfaces | 2.6 × 10−2 | Chin et al., 2020 |

| From state 3 (nontextile surfaces) | |||

| λ31 | Resuspension from nontextile surfaces | 0 | Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ34 | Transfer rate from nontextile surfaces to HCW’s hands | 4.0 × 10−4 | Bean et al., 1982, Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ37 | Inactivation rate of SARS-CoV-2 on nontextile surfaces | 2.1 × 10−3 | van Doremalen et al., 2020 |

| From state 4 (HCW’s hands) | |||

| λ42 | Transfer rate from HCW’s hands to textile surfaces | 2.5 × 10−3 | Bean et al., 1982, Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ43 | Transfer rate from HCW’s hands to nontextile surfaces | 4.0 × 10−2 | Bean et al., 1982, Nicas and Jones, 2009 |

| λ45 | Transfer rate from HCW’s hands to facial membranes | 5.8 × 10−3 | Nicas and Best, 2008, Rusin et al., 2002 |

| λ47 | Inactivation rate of SARS-CoV-2 on HCW’s hands | 2.8 × 10−3 | Hirose et al., 2020 |

Abbreviations: HCW, healthcare worker; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Similar to Nicas and Jones (2009), we assumed three virus loads, i.e., in room air (N 1), on textile surfaces (N 2), and nontextile surfaces (N 3), and assumed that the 0.044 mL of saliva expelled by the patient during a cough were partitioned into 1.4 × 10−6, 0.9, and 0.1, respectively. The partition ratio to N 1 was set to 1.4 × 10−6 in the MCT scenario, which was based on the volume ratio of respirable particles with a diameter < 10 μm to the total volume of droplets in one cough. As mentioned above, the total number of aerosol from one cough with a diameter < 1 μm was extrapolated from the data of Morawska et al. (2009). By adding this volume to the volume of particles with a diameter from 1 to 10 μm, as estimated from the data of the number of droplets expelled during coughing in that diameter range (Loudon and Roberts, 1967), the ratio of the sum of the volume of particles with a diameter < 10 μm to the total volume of particles from one cough [including those with a diameter < 1 μm mentioned above (0.044 mL)] was calculated to be 1.4 × 10−6. In the same way, in the LCT scenario, the partition ratio to N 1 of a vocalization was set to 4.5 × 10−7 using the data of particles emitted from a vocalization corresponding to 30 s of talking. The partition ratio to N 2 and N 3 of 0.9 and 0.1, respectively, was based on the surface area ratio of textile and nontextile surfaces. Other partitions were not considered in this study, such as partition to the surface of the skin and clothes of the HCW, and we assumed that they were partially explained by partition to textile surfaces. The patient was assumed to cough at the same interval; thus, the virus load increased and decreased constantly and was highest just after coughing. Assuming the average virus load during the cough interval to be constant because of the balance of virus loading rate and removal rate, the maximum virus load on each state i (N i, max, i = 1, 2, 3) was calculated as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where RR i is the removal rate of the virus from state i (min−1), i.e., RR 1 = λ 12 + λ 13 + λ 17 + λ 18, RR 2 = λ 27, and RR 3 = λ 37. During this time, virus loss by inhalation by the HCW and patient in the room was not considered because its contribution was negligible; CI is the cough interval (2 min), the inverse of the cough frequency (30 h−1); Pa i is the volume partition ratio of the virus in cough droplets to state i (Pa 1 = 1.4 × 10−6; Pa 2 = 0.9; Pa 3 = 0.1 for the MCT scenario); V saliva is the volume of saliva per one cough (0.044 mL for the MCT scenario); and C saliva is the concentration of the virus in the saliva (mL−1).

The constant average virus load during the cough interval in each state i (N i, ave, i = 1, 2, 3) was calculated as follows:

| (5) |

The exposure dose during the 1 min of caring performed by the HCW was calculated by multiplying the virus load on state i by the transfer probability p ij (n) after 1 min (as calculated above), as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where D h, max and D rpc, max are the maximum exposure doses on the hands and lower respiratory tract of the HCW during the 1 min of caring for the patient, respectively. Moreover, D h, ave and D rpc, ave are the average exposure doses between coughs, respectively. Subsequently, the maximum risk of infection by hand contact and inhalation of respirable particles expelled by coughing during 1 min of care (R1h, max and R1rpc, max, respectively) and the average infection risk between coughs (R1h, ave and R1rpc, ave, respectively) were calculated using Eq. (1), as follows:

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

The k values adopted in this study are described above in Section “2.3. Dose–response assessment.” Cumulative risks were calculated using Eq. (2), as follows:

| (14) |

| (15) |

where N t, wc is the number of 1 min of care with cough and N t, w/oc is that same parameter without cough. We assumed that, during the 8 h work shift, in the MCT scenario, the HCW visited the patient’s room 20 times; thus, the total contact time was 20 min. The patient was assumed to cough once every 2 min. Thus, we assumed that the patient coughed once every 10 out of the 20 visits by the HCW. Therefore, we set N t, wc and N t, w/oc to 10 times, respectively. It should be noted that we assumed that the viruses on the HCW’s hands were removed after each patient visit because of the practice of good hand hygiene.

In the LCT scenario, the total contact time was 60 min during the HCW’s 8 h work shift where the HCW visited the patient 6 times for 10 min each time. Therefore, n of p ij (n) was set to 100,000. In addition, the average virus load during the cough interval may not be constant in the LCT scenario because a patient would talk to the HCW only during the visit. Thus, we considered the transient of the virus load by the patient talking (N i in the LCT scenario) as shown in Fig. S1. Using these averaged N i values during the HCW visit and p ij (100000), exposure doses, the infection risk during 10 min, and the cumulative risks were calculated.

2.4.2. Inhalation of respirable particles from breathing

We assumed that the patient emitted virus-carrying respirable particles by breathing, in addition to coughing and vocalization. The infection risk posed by the viruses emitted by breathing was assessed independently, assuming that the contribution of respirable particles emitted by breathing to the room’s surfaces was negligible. The calculation method was based on Buonanno et al. (2020). First, the emission rate of viruses by breathing (ER v, breath) was estimated as follows:

| (16) |

where ER p is the exhalation rate of the patient (m3 h−1), C rpb, di is the number concentration of respirable particles expelled by breathing with an equilibrium diameter d i (cm−3), and V rpb, di is the volume of respirable particles expelled by breathing (cm3). For ER p, we used a value of 0.37 m3 h−1, as mentioned above. Similar to Buonanno et al. (2020), for C rpb, di, we used the data from Morawska et al. (2009). C rpb, di was 0.084, 0.009, 0.003, and 0.002 cm−3 for d 1 (0.80 μm), d 2 (1.8 μm), d 3 (3.5 μm), and d 4 (5.5 μm), respectively. V rpb, di was calculated assuming that the particles were spheres with twice the equilibrium diameter, because we assumed that the equilibrium diameter is half of the initial diameter by desiccation (Nicas et al., 2005).

The concentration of virus in the air originating from the patient’s breath [C v, air, (mL−1)] was assumed in the steady state and was calculated as follows:

| (17) |

where RR v, air is the removal rate of the virus from the room air (h−1), which is the same as RR 1, a summation of λ 12, λ 13, λ 17, and λ 18 (min−1) (Yang and Marr 2011), and V r is the volume of the hospital room (22.7 m3).

The exposure dose and infection risk of respirable particles by breathing for the HCW during one visit in the MCT scenario (visiting time, t vt = 1 min) (D rpb and R1rpb, respectively) were calculated as follows:

| (18) |

| (19) |

where IR is the inhalation rate of the HCW (1.5 × 10−2 m3 min−1).

The infection risk of respirable particles by breathing during working hours was calculated as follows:

| (20) |

where t ct is the contact time of the HCW during working hours (the number of 1 min, 20 and 60 in the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively).

2.4.3. Inhalation of inspirable particles from cough and vocalization

The size distribution of droplets expelled by one cough and vocalization was obtained from the data reported by Loudon and Roberts (1967) regarding the number of droplets expelled during coughing and talking (Table S2). Chen et al. (2020b) reported that the droplets within the small size group (<75 μm) to the large size group (>400 μm) expelled by the infected person during coughing and talking can reach the facing susceptible person for example within a distance of 0.6 m if the air stream is considered. Therefore, we used the size category for all particles in Table S2 for the inspirable particles, assuming that all sizes of particles approached the face and were inhaled through the nostrils. The exposure dose via the inhalation of inspirable particles after one cough (and one vocalization) in each particle size category i (D ip, i) was calculated as follows:

| (21) |

where V p, i is the volume of a particle in size category i, thus, the product of C saliva and V p, i is the number of viruses contained in one particle in size category i. V p, i was calculated using the methods described in Nicas et al., 2005, Nicas and Sun, 2006; N p, i is the mean number of droplets from one cough in size category i (Table S2), P id is the probability of inhalation of droplets after one cough (and one vocalization) (Table S3), AE i is the aspiration efficiency from nostrils in size category i (calculated using the method in Chen et al. 2020b, Table S2), thus, the product of N p, i, P id, and AE i is the number of inspirable particles inhaled directly via the air stream of coughing and talking in size category i. In addition, we assumed that the particles not deposited on the HCW’s face distributed between the HCW and patient and were inhaled by the HCW. P ip is the probability of inhalation of inspirable particles after one cough (and one vocalization) (0.054, Table S3), DE i is the deposition efficiency on the HCW face in size category i (calculated using the method in Chen et al. 2020b, Table S2). thus, the product of N p, i, P ip, and (1 − DE i) is the number of inhaled inspirable particles which were not deposited on the HCW’s face after one cough (and one vocalization) in size category i. In the MCT scenario, the mean number of droplets from one cough was used as N p, i (Table S2). In the LCT scenario, the number of inhaled inspirable particles from one cough and talking (counting from one to 30) were calculated respectively using the mean number of droplets from one cough and talking and AE i and DE i when coughing and talking (Table S2) and were summed. The counting from one to 30 was assumed to correspond to 30 s of talking by the patient and, for simplicity, it was assumed that 30 s of talking and a cough occurred at the same time, as mentioned above. We used a P id value of 0.0069, and we assumed that the HCW’s mouth was closed while breathing and the air was inhaled only through the nostrils (with a surface area of 2 cm2). The calculation method is indicated in Table S3 (Chen et al., 2020b). Because both (C saliva ∙ V p, i) and (N p, i ∙ P id ∙ AE i + N p, i ∙ P ip ∙ (1 - DE i)) were assumed to follow a Poisson distribution, the product of them did not follow a Poisson distribution. Therefore, the infection risk by inspirable particles from one cough (and one vocalization) (R1ip, i) was calculated using the following equation:

| (22) |

The total risk of inspirable particles (R1ip) was calculated via an inclusion–exclusion method using R1ip, i. The risk calculated above was a conditional probability (HCW approaching the patient). Therefore, R1ip, i was multiplied by the approaching probability [P a = 0.0064, Table S3 (Canova et al., 2020)], and the infection risk by inspirable particles from coughing (and vocalization) during one work shift (R ip) was calculated as follows:

| (23) |

where N c is the number of coughs during the care period, i.e., 10 and 30 in the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively.

2.4.4. Droplet spray to face membranes

As mentioned in the previous subsection, we assumed that the particles of all sizes reached the face membranes of the HCW based on the study by Chen et al. (2020b). Therefore, we used the size category for all particles in Table S2 (Loudon and Roberts, 1967) for the droplet spray. The exposure dose corresponding to droplet spray on face membranes after one cough (and one vocalization) in each particle size category i (D df, i) was estimated as follows:

| (24) |

where P df is the probability of the droplets reaching the face membranes after one cough (and one vocalization) (0.045, Table S3), thus, the product of N p, i, P df, and DE i is the number of droplets that reached the face membranes in size category i. Similar to that described for the inhalation of inspirable particles in Section 2.4.3, the product of (C saliva ∙ V p, i) and (N p, i ∙ P df ∙ DE i) did not follow a Poisson distribution. The infection risk by droplet spray from one cough (and one vocalization) (R1df, i) was calculated using the following equation:

| (25) |

The total risk of droplet spray (R1df) was calculated via an inclusion–exclusion method using R1df, i. The risk calculated above was a conditional probability (HCW facing the patient). Therefore, R1df, i was multiplied by the facing probability (P f = 0.013, Table S3), and the infection risk by droplet spray from coughing (and vocalization) directly during one work shift (R df) was calculated as follows:

| (26) |

2.4.5. Droplet spray to hands and hand contact

In addition to droplet spay to face membranes, we considered droplet spray to hands and, subsequently, to face membranes contacted by fingertips. The exposure dose and infection risk of droplet spray to hands and then to face membranes after one cough (and one vocalization) in each particle size category i (D dh, i and R1dh, i, respectively) were estimated as follows:

| (27) |

where RR h is the removal rate of the virus from the hands (min−1), which is a summation of λ42, λ43, λ45, and λ47, P dh is the probability of reaching the fingertips of the hands after one cough (and one vocalization) (0.035, Table S3), thus, the product of N p, i, P dh, and DE h, i is the number of droplets that reached the HCW’s hands in size category i. We used DE i which is the deposition efficiency on the HCW’s face as the deposition efficiency on the HCW’s hand assuming the size of a head and a hand was same. Because the product of (C saliva ∙ V p, i) and (N p, i ∙ P dh ∙ DE h, i) did not follow a Poisson distribution, as for the inhalation of inspirable particles, the infection risk by droplet spray from one cough (and one vocalization) (R1dh, i) was calculated using the following equation:

| (28) |

The total risk of droplet spray (R1dh) was calculated via an inclusion–exclusion method using R1df, i. The risk calculated above was a conditional probability (HCW facing the patient). Therefore, R1dh, i was multiplied by the facing probability (P f = 0.013, Table S3), and the infection risk by droplet spray from cough (and vocalization) directly during one work shift (R dh) was calculated as follows:

| (29) |

2.4.6. Overall infection risk

The overall infection risk was calculated via an inclusion–exclusion method using R h, R rpc, R rpb, R ip, R df, and R dh.

2.5. Evaluation of intervention effects

To evaluate the effects of nonpharmaceutical interventions, we calculated the infection risk of the HCW while wearing a face mask, a face shield, and a face mask plus a face shield, as well as with the patient wearing a face mask, in the MCT and LCT scenarios. Moreover, we used 0.246 as k for pathways (5) and (6) (inhalation of respirable particles from cough (and vocalization) and from breathing, respectively), to estimate worst case of infection risk. We assumed that a face mask prevents the exposure of the nostrils and lips to hand contact and droplet spray; as a result, virus exposure occurred only on eyes, which decreased the exposure area to 0.4 (6 cm2 / 15 cm2; Chen et al., 2020b) and touching frequency of a hand to facial membranes to one third of that with no PPE (touching frequency of 27% was the eyes and 6% was a combination of the mouth, the nose, and the eyes; Kwok et al., 2015). In addition, we assumed that a face mask reduced the inhalation of particles by the filtration efficiency of particles in each diameter range. The filtration efficiency used in this study was taken from the report by Leonard et al. (2020), which in turn was based on the data for surgical masks described by Chen and Willeke (1992); the data for particles with a size of 4 μm or above, which were not included in Chen and Willeke’s article, were extrapolated. These values are indicated in Table S2, together with particle diameters. Note that, in the case of the HCW wearing a face mask, the filtration efficiency of the equilibrium diameter was used, whereas in the case of the patient wearing a face mask, the filtration efficiency of the initial diameter was used. In addition, we assumed that a face shield would prevent the exposure of face membranes to hand contact, inhalation of particles directly via the air stream of cough and talking, and droplet spray. In turn, the inhalation of particles not deposited on the HCW face was not assumed to be prevented by a face shield; thus, the infection risk of the HCW when wearing a face shield stemmed only from the inhalation of inspirable particles not deposited on the HCW face and respirable particles.

Additionally, to assess the effect of ventilation, we calculated the infection risk of the HCW with an air change rate of 6 h−1 in case of the patient wearing a face mask.

2.6. Calculation methods

Risk estimation of pathways (2), (3), and (4) was performed using the Monte Carlo simulation method to incorporate uncertainty and variability in the risk characterization (Adhikari et al., 2019, Azuma et al., 2013). Calculations were performed using @Risk 8.0 (Palisade Corporation, Ithaca, NY, USA) (n = 105), assuming a Poisson distribution for the number of viruses contained in one particle, the number of inhaled particles, the number droplets that reached the face membranes, and the number of droplets that reached the HCW’s hands.

2.7. Consideration of uncertainties and cumulative risk in a week and a month

Some parameters had uncertainties that could not be controlled by the scenario settings. To consider the uncertainty of virus concentration in the saliva, for example, C saliva was varied from 101 to 108 mL−1 and the infection risk was calculated for each concentration. In addition, as a dose–response function parameter, k of 0.00246 and 0.246 were used for pathways (5) and (6) and a k of 0.00246 was used for all other pathways. Moreover, to consider the variation in saliva volume and k, an upper limit of the infection risk was calculated using saliva volume and particle number + 10%, and the 95 percentile value of k with normal distribution [0.00459 (Mitchell and Weir, 2020) or 0.459 for respirable particles]. In addition, as a lower limit, the infection risk was calculated using saliva volume and particle number − 10%, and the 5 percentile value of k with normal distribution [0.00135 (Mitchell and Weir, 2020) or 0.135 for respirable particles]. These values were indicated in the description of the variation of the infection risk.

Additionally, to assess the risks of repeated exposure of the HCW in longer working periods, the cumulative overall risks in a week (5 days) and a month (20 days) for the MCT scenario using k = 0.246 for pathways (5) and (6) were calculated in cases with and without intervention using Eq. (2).

3. Results

3.1. Estimation of the infection risk

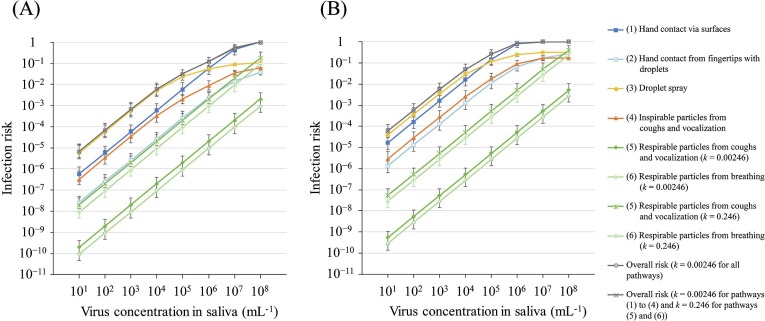

The risks of each pathway and the overall risk depending on C saliva in the MCT and LCT scenarios are shown in Fig. 2 and Tables S4 and S5. The overall risk did not vary largely when using different k values (0.00246 and 0.246) for the infection risk of respirable particles (the differences were within 3% of the mean value). In the MCT scenario, the overall risk was below 0.01 for C saliva of 104 mL−1, 0.12 for C saliva of 106 mL−1, above 0.5 for C saliva of 107 mL−1, and 1.0 for C saliva of 108 mL−1. Moreover, in the LCT scenario, the overall risk was below 0.01 for C saliva of 103 mL−1, 0.27 for C saliva of 105 mL−1, 0.87 for C saliva of 106 mL−1, and 1.0 for C saliva of 107 mL−1 and more. Table S5 also shows the relative risk (RR) of the overall risk in the MCT scenario to that in the LCT scenario. This RR was 7.1–8.5 for C saliva of 101–106 mL−1, suggesting that infection in the LCT scenario is 7.1–8.5 times higher than that in the MCT scenario in the corresponding C saliva.

Fig. 2.

Absolute infection risk from each pathway and overall risk according to the Csaliva in the MCT scenario (A) and the LCT scenario (B). Vocalization was only in the LCT scenario. The upper limit of error bar indicates the infection risk using saliva volume and particle number + 10%, and the 95 percentile value of k with normal distribution and the lower limit of error bar indicates the infection risk using saliva volume and particle number − 10%, and the 5 percentile value of k with normal distribution.

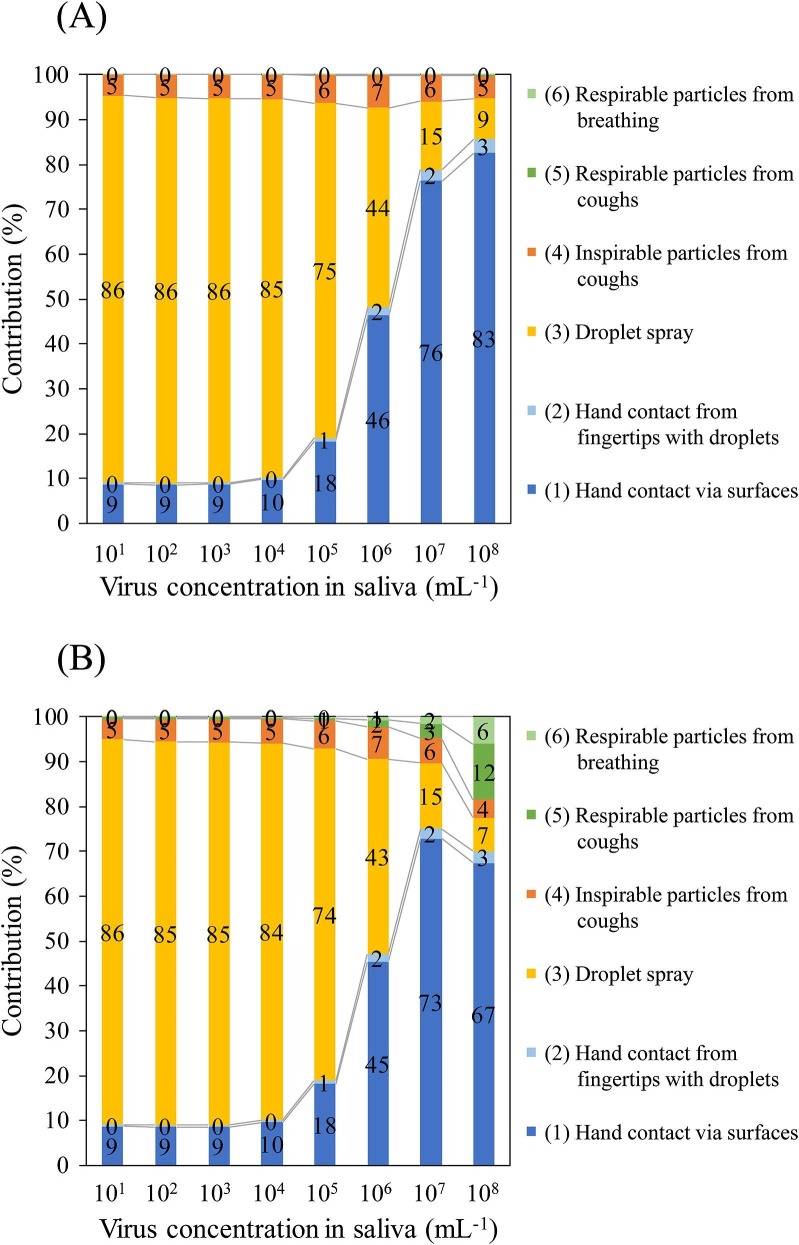

The risks of each pathway and their contribution ratios according to different k values in the MCT and LCT scenarios are shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4 , respectively. Note that the contribution is the ratio of each absolute risk from the pathways to the sum of the absolute risks from all six pathways. In the MCT scenario at C saliva of 101 to 105 mL−1 and in the LCT scenario at C saliva of 101 to 104 mL−1, droplet spray was the major contributing pathway to infection (60%–86%), followed by hand contact via contaminated surfaces (9%–32% contribution) and inhalation of inspirable particles (5%–6% contribution). However, the contribution ratio of droplet spray decreased as the C saliva increased because the increase in the absolute risk of infection from droplet spray that accompanied the increase in C saliva was reduced compared with the other pathways. Therefore, at a high virus concentration in the saliva (106–108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 105–108 mL−1 in the LCT scenario), hand contact via contaminated surfaces was the highest contributor (41%–83%) to infection. The contribution of inhalation of inspirable particles was 4%–10% in all assumed cases. The logarithm of the infection risk of respirable particles from cough (and vocalization) increased linearly according to the C saliva (Fig. 2); thus, their contribution at a C saliva of 107 and 108 mL−1 in the case of k = 0.246 was 3% and 12%–17%, respectively. Similar to that observed for respirable particles from cough (and vocalization), the infection risk of respirable particles from breathing increased, resulting in a contribution at C saliva of 107 and 108 mL−1 in the case of k = 0.246 of 2% and 6%–10%, respectively. Consequently, the sum of the contribution of respirable particles was 5% and 18%–27%, respectively, for C saliva of 107 and 108 mL−1 in the case of k = 0.246. Moreover, the contribution of the infection risk from hand contact from the direct contamination of fingers with droplets was in the range of 0% to 3% in the MCT scenario and 2% to 16% in the LCT scenario at all C saliva.

Fig. 3.

Contribution of the infection risk from each exposure pathway in the MCT scenario using k = 0.00246 for all pathways (A) and k = 0.00246 for pathways (1) to (4) and 0.246 for pathways (5) and (6) (B). The number on the bar indicates the contribution (%).

Fig. 4.

Contribution of the infection risk from each exposure pathway in the LCT scenario using k = 0.00246 for all pathways (A) and k = 0.00246 for pathways (1) to (4) and 0.246 for pathways (5) and (6) (B). The number on the bar indicates the contribution (%).

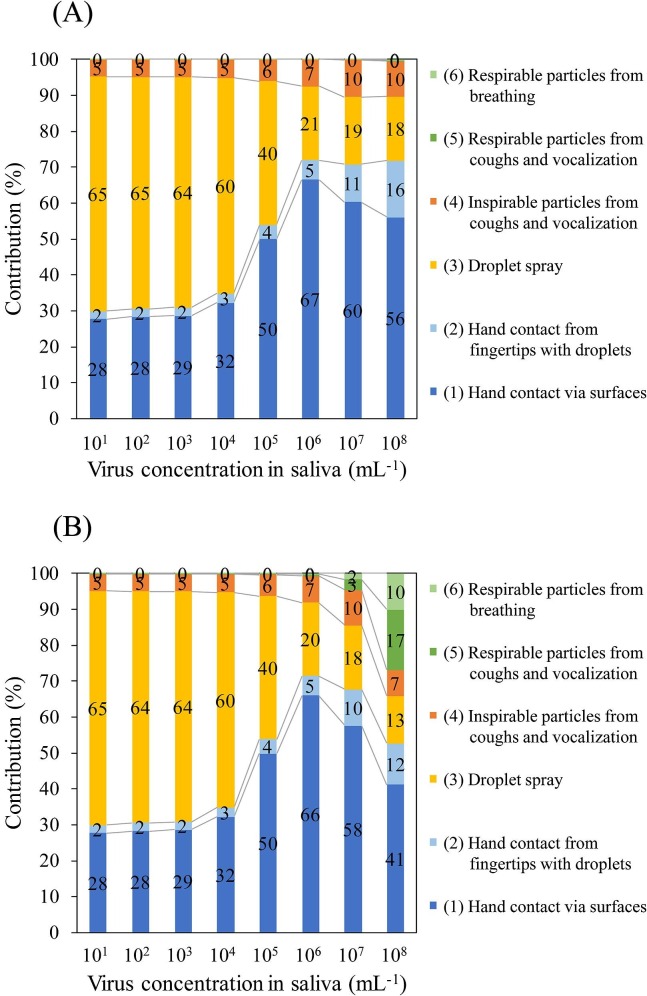

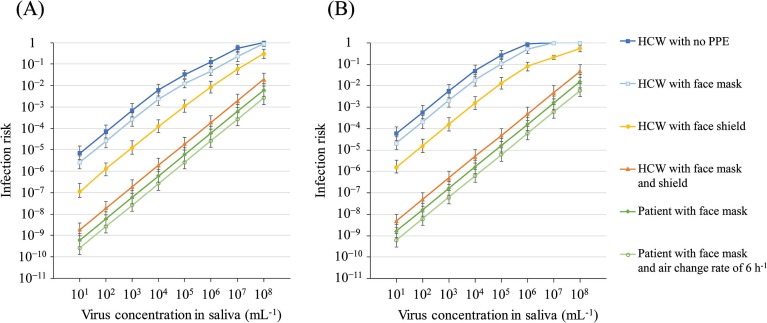

3.2. Effective interventions

The overall risks of infection of the HCW with no PPE, with a face mask, with a face shield, and with a face mask plus a face shield, as well as with the patient wearing a face mask and with the patient wearing a face mask and air change rate of 6 h−1, in the MCT and LCT scenarios are shown in Fig. 5 and Table S6. The contribution ratio from each pathway in each nonpharmaceutical intervention are shown in Figs. S2 to S6. The overall risk of infection of the HCW with a face mask in the MCT and LCT scenarios was decreased compared with that with no PPE, and was 0.01 at C saliva of 105 mL−1, 0.23 at C saliva of 107 mL−1, and 0.88 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario; and 0.02 at C saliva of 104 mL−1, 0.11 at C saliva of 105 mL−1, 0.52 at C saliva of 106 mL−1, and 1.0 at C saliva of 107 mL−1 and more in the LCT scenario, suggesting that, even when wearing a face mask, the HCW becomes infected with a high probability in the case of a patient with a high virus concentration in the saliva; for example, the risk was 0.88 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 1 at C saliva of 107 and 108 mL−1, in the LCT scenario.

Fig. 5.

Overall risk in the presence of nonpharmaceutical interventions in the MCT scenario (A) and the LCT scenario (B) using k = 0.00246 for pathways (1) to (4) and 0.246 for pathways (5) and (6). The upper limit of error bar indicates the overall risk using saliva volume and particle number + 10%, and the 95 percentile value of k with normal distribution and the lower limit of error bar indicates the overall risk using saliva volume and particle number − 10%, and the 5 percentile value of k with normal distribution.

The overall risk of the HCW when wearing a face shield in the MCT and LCT scenarios also decreased compared with that observed with no PPE, and was 0.01 at C saliva of 106 mL−1, 0.06 at C saliva of 107 mL−1, and 0.30 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario; and 0.01 at C saliva of 105 mL−1, 0.08 at C saliva of 106 mL−1, 0.22 at C saliva of 107 mL−1, and 0.56 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the LCT scenario, suggesting that, as for the face mask, even when wearing a face shield, the HCW becomes infected with a high probability in the case of a patient with a high virus concentration in the saliva; for example, 0.30 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 0.22 and 0.56 at C saliva of 107 and 108 mL−1, respectively, in the LCT scenario.

When the HCW wore a face mask plus a face shield, the logarithm of the infection risk increased linearly according to C saliva (Fig. 5) and was below 0.002 at C saliva of 101–107 mL−1 and 0.02 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario, and below 0.005 at C saliva of 101–107 mL−1 and 0.05 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the LCT scenario, suggesting that the infection risk of the HCW when wearing both a face mask and a face shield was reduced by no more than 0.05 (the worst case assumed in this study) because of the prevention of the exposure to hand contact, a part of inhalation of inspirable particles, and droplet spray by the face shield and the reduction of the inhalation of respirable and inspirable particles by the face mask.

When the patient wore a face mask, the overall risk of the HCW was lower compared with HCW wearing a face mask and/or shield, and was below 0.001 and 0.002 at C saliva of 101–107 mL−1 in the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively. The overall risk of infection was highest at C saliva of 108 mL−1, i.e., 0.01 and 0.02 in the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively.

When the patient wore a face mask and the air change rate was 6 h−1, the absolute risk decreased compared with above values and the RR to that when the patient wore a face mask and the air change rate of 2 h−1 (default setting) was approximately 0.4.

3.3. Cumulative overall risk in a week and a month

The cumulative overall risks of infection of the HCW in a week and a month in the MCT scenario are shown in Table S7. The overall risk increased to 0.03 for C saliva of 104 mL−1, 0.98 for C saliva of 107 mL−1, and 1.0 for C saliva of 108 mL−1 in a week, and 0.01 for C saliva of 103 mL−1, 0.93 for C saliva of 106 mL−1, and 1.0 for C saliva of 107 mL−1 and more in a month.

4. Discussion

We calculated the infection risk of COVID-19 from multiple pathways of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in health-care settings and estimated the relative contribution of each pathway. On a whole, the overall risk was 1 for C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 107 mL−1 and greater in the LCT scenario, suggesting that, when the virus concentration in the saliva was high, an HCW with no PPE could be infected during an 8 h work shift, which is more likely in the case of a longer caring time, including when the HCW and patient have a conversation. The relative contribution ratio varied according to C saliva; by combining two scenarios of middle and long contact time, at low to middle C saliva, for example 101–105 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 101–104 mL−1 in the LCT scenario, direct transmission from droplet spray was the predominant contributor to infection (i.e., 60%–86%), whereas the contribution of indirect transmission from hand contact via contaminated surfaces (fomite) increased to 41%–83% at a higher C saliva (106–108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 105–108 mL−1 in the LCT scenario). The contribution ratio of droplet spray decreased as C saliva increased, because, at a high C saliva, the infection risk was almost one if the droplet reached the face membranes; therefore, the infection risk from droplet spray was limited by the probability of the droplets reaching the face membranes. Instead, the contribution of hand contact increased with the increase of C saliva. This tendency of droplet spray was similar to the data obtained for infection with influenza A in a residential bedroom simulated by Nicas and Jones (2009), who concluded that, with the increase in virus saliva concentration, the pathways of inhalation of respirable and inspirable cough particles increase in importance, while the prominence of the pathway of spray of cough droplets onto facial membranes decreases. The contribution ratio of inspirable particles also decreased as C saliva increased, for the same reason as with the droplet spray because particles of all sizes approached the face and were inhaled through the nostrils. Chen et al. (2020b) found that the short-range airborne route of the virus (which corresponds to inhalation of the inspirable particles in the present study) dominates the exposure of respiratory infection during close contact. In the present study, we assumed that the HCW’s mouth was closed when breathing and the air was inhaled only through the nostrils, which was different from Chen et al.’s study. If the HCW’s mouth was open during the periods of patient’s coughing and talking, the contribution of inhalation of inspirable particles would be comparable or more dominant than that of the droplet spray at a distance of 0.6 m between the HCW and patient. In any case, it may be deduced that the direct transmission in close contact by droplet spray and inhalation of inspirable particles would be dominant at low to middle C saliva. Comparing the contribution of each pathways between the scenarios, the contribution ratio of hand contact in the LCT scenario (28%–67%) was higher than that in the MCT scenario (9%–46%) at C saliva of 101–106 mL−1. This is attributed to the difference of frequency of hand hygiene, that is hand hygiene was performed after each patient visit; thus, the virus on the HCW’s hands accumulated during 1 min visit in the MCT scenario and 10 min visit in the LCT scenario. In addition, airborne transmission from patient’s cough and vocalization (only when the patient had a conversation) occurred, with a contribution ratio in the range of 3%–17% in the case of a higher C saliva (107 and 108 mL−1) and a k of 0.246. Moreover, in the same case, airborne transmission from patient’s breathing occurred with a contribution ratio in the range of 2%–10% in the case of a higher C saliva (107 and 108 mL−1) and a k of 0.246. A scientific brief by the WHO (2020c) reported as one of main findings that “urgent high-quality research is needed to elucidate the relative importance of different transmission routes; the role of airborne transmission in the absence of aerosol generating procedures; ” In this study, in accordance with the WHO’s suggestion, we inferred the relative contribution of each pathway of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in a health-care setting based on the current knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 and its related information. Moreover, we suggested that airborne transmission is not negligible if visiting a patient with a high concentration of virus in the saliva.

Regarding the SARS-CoV-2 concentration in the saliva, To et al. (2020a) reported that 2019-nCoV was detected in the initial saliva specimens of 11 patients and that the median viral load of the first available saliva specimens was 3.3 × 106 copies mL−1 (range, 9.9 × 102 to 1.2 × 108 copies mL−1). In addition, To et al. (2020b) reported that the median viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva or other respiratory specimens at presentation was 5.2 log10 copies mL−1 (IQR, 4.1–7.0). Wyllie et al. (2020) reported and indicated that the mean value was 5.58 log10 copies mL−1 (95% CI 5.09–6.07) in the range from < 104 to > 1010. Assuming that the conversion factor from RNA copies to PFU was 103 (Munster et al., 2020, Uhteg et al., 2020), the median SARS-CoV-2 concentration in the saliva is assumed to be between 102 and 104 mL−1 in the range from < 1 to > 107 mL−1 based on the above-mentioned data. Therefore, the range of C saliva set in this study (from 101 to 108 mL−1) almost overlapped with the possible concentration of virus in the saliva of patients with COVID-19. At the probable median concentration of 102–104 mL−1, the predominant pathway was droplet spray (>80%), followed by the contribution of hand contact via surfaces (9%–10%) in the MCT scenario, suggesting that droplet spray and hand contact are the most likely transmission pathways of SARS-CoV-2, similar to that reported previously (Burke et al., 2020, Chan et al., 2020, Huang et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020a).

Bao et al. (2020) performed a simulation of three transmission modes, i.e., close contact, respiratory droplets, and aerosol routes, of SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory using hACE2 mice. They found that the virus could be highly transmitted among naive hACE2 mice via close contact (7 out of 13 naive hACE2 mice in the same cage with 3 infected mice showed seropositivity). Regarding respiratory droplets, among 10 naive hACE2 mice separated by grids from 3 infected mice, 3 showed seropositivity. Via aerosol inoculation, hACE2 mice could not be experimentally infected. Close contact is an accumulation mode for various transmission routes (Bao et al., 2020). Therefore, we can assume that the risk of close contact is the overall risk, and using absolute risk of droplet transmission (3/10) and overall risk (7/13) and considering inclusion and exclusion of contact transmission, the contribution of droplet transmission was calculated as 47%, which indicated that droplet transmission is the major pathway of infection of SARS-CoV-2. This tendency was consistent with the data calculated in the present study. Mice contact virus via the hair by grooming, which makes the risk of close contact higher and the contribution of droplet transmission lower compared with humans. This assumption also consistent with the results in the present study.

By modeling multiple exposure pathways, the effectiveness of various interventions could be assessed. Table 2 show the RR compared with the absolute risk of infection of the HCW with no PPE in addition to the overall risks for the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively. Note that a k value of 0.246 was used for pathways (5) and (6). In the case when the HCW wore a face mask, the RR was 0.37–0.42 at C saliva of 101–107 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 0.36–0.40 at C saliva of 101–105 mL−1 in the LCT scenario because the exposure dose of the highly contributing pathways of hand contact and droplet spray (Fig. S2) decreased to approximately one third (touching frequency of a hand to facial membranes) and 0.4 (area proportion of eyes to face membranes), respectively. This was because of the decrease of the exposure area of the face membranes to only the eyes (where the nostrils and lips were covered by the face mask). The RR was 0.88 at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and 0.59–1.0 at C saliva of 106–108 mL−1 in the LCT scenario, because in the case of a high C saliva, the absolute risk was close to 1 and did not increase over 1; thus, the RR of the HCW when wearing a face mask became relatively higher. In the case when the HCW wore a face shield, the RR was below 0.1 at C saliva of 101–106 mL−1 and increased from 0.11 to 0.30 at C saliva of 107–108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario. It was below 0.1 at C saliva of 101–106 mL−1 and increased from 0.22 to 0.56 at C saliva of 107–108 mL−1 in the LCT scenario. This was because the infection risk from the inhalation of inspirable and respirable particles increased according to C saliva (the contributions were in Fig. S3), which could not be prevented completely by wearing a face shield; therefore, the RR increased depending on C saliva.

Table 2.

Relative risk (RR) of overall risk by nonpharmaceutical interventions to no intervention in the MCT and LCT scenarios.

|

Csaliva (mL−1) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | |

| MCT scenario | ||||||||

| HCW with a face mask | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.88 |

| HCW with a face shield | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.020 | 0.033 | 0.070 | 0.11 | 0.30 |

| HCW with a face mask and shield | 2.8 × 10−4 | 2.7 × 10−4 | 2.8 × 10−4 | 3.1 × 10−4 | 5.9 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 3.6 × 10−3 | 0.019 |

| Patient with a face mask | 8.7 × 10−5 | 8.6 × 10−5 | 8.7 × 10−5 | 9.8 × 10−5 | 1.8 × 10−4 | 4.9 × 10−4 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 6.0 × 10−3 |

| Patient with a face mask and air change rate of 6 h−1 | 3.8 × 10−5 | 3.8 × 10−5 | 3.8 × 10−5 | 4.3 × 10−5 | 8.1 × 10−5 | 2.2 × 10−4 | 4.9 × 10−4 | 2.6 × 10−3 |

| LCT scenario | ||||||||

| HCW with a face mask | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| HCW with a face shield | 0.026 | 0.027 | 0.028 | 0.031 | 0.048 | 0.095 | 0.22 | 0.56 |

| HCW with a face mask and shield | 8.4 × 10−5 | 8.6 × 10−5 | 8.7 × 10−5 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 1.8 × 10−4 | 5.6 × 10−4 | 4.9 × 10−3 | 0.048 |

| Patient with a face mask | 2.8 × 10−5 | 2.8 × 10−5 | 2.9 × 10−5 | 3.3 × 10−5 | 5.9 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 0.016 |

| Patient with a face mask and air change rate of 6 h−1 | 1.0 × 10−5 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−5 | 2.2 × 10−5 | 7.0 × 10−5 | 6.1 × 10−4 | 6.1 × 10−3 |

RR to the overall risk of an HCW with no PPE in the MCT scenario using k = 0.00246 for pathways (1) to (4) and k = 0.246 for pathways (5) and (6). Abbreviations: HCW, healthcare worker; LCT, long contact time; MCT, medium contact time; PPE, personal protective equipment; RR, relative risk.

In the above-mentioned assumed range of 102–104 mL−1 of C saliva, the RR was 0.36–0.37, 0.02–0.03, and < 4.0 × 10−4 for an HCW wearing a face mask, a face shield, and both of them, respectively, suggesting that PPE decreased the infection risk by 63% to > 99.9%. These results also suggest that the effectiveness of face shields may be better than that of face masks. However, if the concentration of the virus in the patient’s saliva is high, e.g., C saliva of 107–108 mL−1, the absolute risk and RR of an HCW wearing a face shield increased, i.e., 0.06–0.56 and 0.11–0.56, respectively. Therefore, the combination of a face mask with a shield would be necessary in health-care settings. When the patient wore a face mask, the RR and infection risk were < 1.0 × 10−4 at C saliva of 102–104 mL−1 in the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively; thus, the use of face masks by patients is effective. Nevertheless, it may be difficult for the patient to use a mask at any time, and the patient may remove the mask unconsciously when talking with a HCW. Therefore, the use of PPE by HCWs is mandatory. The residual risk when the patient wore a face mask was mainly attributed to inhalation of respirable particles (Fig. S5) and the absolute overall risk was 0.01 and 0.02 for C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT and LCT scenarios, respectively (Table S6), which was not negligible. The effective intervention for respirable particles is ventilation. The results showed that the overall risk with the use of a patient mask decreased linearly depending on the air change rate (approximately 0.4 of when the patient wore a face mask and the air change rate was 2 h−1). The RR was < 5.0 × 10−5 at C saliva of 102–104 mL−1. These results suggested the effectiveness of ventilation for respirable particles.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV in health-care and non-health-care settings were conducted by Chu et al. (2020). For comparison with the results of this study, we referred to the RR and absolute risk values, i.e., face masks including surgical masks and N95 respirators could result in a large reduction in risk (RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.45; absolute risk, 3.1% with face mask vs. 17.4% with no face mask as a total; RR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.41 in health-care settings; and RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.79 in non-health-care settings). Considering the absolute risk value, 17.4% is near the value of 0.12 (12%) observed at C saliva of 106 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and between 0.049 and 0.27 (4.9%–27%) at C saliva of 104–105 mL−1 in the LCT scenario (Table S6). A direct comparison is difficult because the exposure time may have been different between the simulated data of 1 day and the epidemiological data of varying lengths of time; however, assuming that, the contribution ratios of each exposure pathway was maintained in the possible C saliva range because of the linear relationship between the absolute risks and the exposure amounts, the corresponding RR of an HCW wearing a face mask was 0.38 and 0.37–0.40 (Table 2) and the absolute risk was 0.047 (4.7%) and 0.018–0.11 (1.8%–11%) (Table S6), which were similar to the RR of 0.34 and around the absolute risk of 3.1% reported for face masks in the review, respectively. In addition, eye protection, including visors, face shields, and goggles, was also associated with a lower infection risk (RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.52; absolute risk, 5.5% with eye protection vs. 16.0% with no eye protection). An absolute risk of 16.0% is also close to the value of 0.12 (12%) observed at C saliva of 106 mL−1 in the MCT scenario and between 0.049 and 0.27 (4.9%–27%) at C saliva of 104–105 mL−1 in the LCT scenario (Table S6). The corresponding RR of an HCW wearing a face shield was 0.07 and 0.03–0.05 (Table 2) and the absolute risk was 0.009 (0.9%) and 0.002–0.013 (0.2%–1.3%) (Table S6), which were lower than the RR of 0.34 and the absolute risk of 5.5% afforded by eye protection (as reported in the review). This is because we simulated the effectiveness of a face shield, which can protect the whole face area, resulting in a higher RR compared with the RR afforded by eye protection, including equipment that partially protects the face. In addition, the RR of an HCW wearing a face mask and shield, as well as when the patient wore a face mask, were < 2.0 × 10−3 and < 5.0 × 10−4, respectively at these C saliva.

The settings of the LCT scenario were based on an actual case of COVID-19 infection in a health-care setting. Based on the report of this infection status, it was speculated that droplets from a patient attached to the nurse’s hands for some reason, and that the nurse was infected by touching the face (Kawada et al., 2020). Therefore, we considered the infection risk from hand contact via fingers directly contaminated by droplets, in addition to hand contact via contaminated surfaces, resulting in a contribution ratio of 2% to 16%; moreover, the sum of the contribution of the risk of hand contact from two assumed pathways was in the range of 30% to 72% in the LCT scenario, suggesting that hand contact is a possible pathway of infection in the context of care with a longer contact time, including conversation.

Our study had several limitations. We used alternative data for which the data of SARS-CoV-2 has not been available so far, such as the dose–response function parameter k and the transfer rate between the HCW’s hands and surfaces or facial membranes (λ24, λ34, λ42, λ43, and λ45). The alternative data were selected from equivalent values of surrogates based on their similarity to SARS-CoV-2, as much as possible. In addition, k for inhalation of respirable particles was 100 times more than that for other pathways as a conservative measure, which may overestimate the risk associated with inhalation of respirable particles. When using k value of 10 times than that of other pathways, the risk and contribution of respirable particles decreases to approximately one tenth (e.g., the absolute risk and the contribution were 0.003 and 1% in C saliva of 107 mL−1 and 0.03 and 2% for C saliva of 108 mL−1, respectively, in the MCT scenario). It is more reasonable to assume that the risk and contribution of respirable particles varied between those by 10 to 100 times of k (e.g., the absolute risk and the contribution were from 0.003 to 0.03 and from 1% to 5% at C saliva of 107 mL−1 and from 0.03 to 0.27 and from 2% to 18% at C saliva of 108 mL−1 in the MCT scenario). Moreover, it should be noted that considered virus concentration in the saliva of 107 and 108 mL−1 were rare cases (Wyllie et al., 2020). In the present study, we only considered the close contact distance of 0.6 m between the HCW and the patient and the effect by the difference of the distance was not considered. Therefore, the results obtained in the present study cannot be generalized to other settings and scenarios of different distance between the susceptible person and the infected person. The results are valid for possible health-care settings in the physical distance of 0.6 m while caring. In other settings with a longer distance such as dining at a restaurant, the contributions from each infection pathway may be different from the conclusions in this study, thus we would further study scenarios of the other settings in the future study. To consider the uncertainties attributed to these limitations, the exposure modeling and risk assessment in the present study were simplified including a variety of cases in health-care settings. The consistency between our data and those reported by other studies using animal experiments, epidemiological data, and clinical findings may confirm the probability of the parameters and models. Thus, we deduced that the results described the typical and possible cases of the risk of COVID-19 from multiple pathways of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 of HCWs in health-care settings. Finally, to improve the accuracy of the model, it is desirable to update to data pertaining to SARS-CoV-2 in future studies.

5. Conclusion

A risk assessment of COVID-19 infection in an HCW via multiple pathways of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in health-care settings of short distance of 0.6 m between the HCW and a patient while caring at a virus concentration in the saliva of 101–104 mL−1 revealed that droplet spray was the major pathway contributing to infection, followed by hand contact via contaminated surfaces. At a high virus concentration in saliva (from 106 to 108 mL−1), hand contact via contaminated surfaces was the most prominent pathway. The contribution of the inhalation of respirable particles increased with the increase of virus concentration in the saliva and was comparable to those of other pathways at the high virus concentration in saliva in the assumed scenarios, although these were worst and rare cases. The results of the assessment of the effectiveness of nonpharmaceutical interventions suggest that, to reduce the infection risk sufficiently, HCWs should use both a face mask and a face shield. The major contributing factors for infection among HCWs include the lack of understanding of the disease, inadequate use and unavailability of PPE, and uncertain diagnostic criteria. Improved knowledge on the characteristics of the infectious disease, adequate education and training of HCWs, sufficient stocks of PPE, and adequate preventive behaviors are essential for the prevention of COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, based on the method used in this study, the infection risks in other settings of concern such as dining at a restaurant which includes different parameters of physical distance, etc. should be clarified in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Atsushi Mizukoshi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Chikako Nakama: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Jiro Okumura: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Kenichi Azuma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Resources, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by an ALL-KINDAI UNIVERSITY SUPPORT PROJECT AGAINST COVID-19 (Research project 5) provided by the Kindai University. We thank Dr. Shoichi Morimoto, SHINRYO Corporation for his helpful comments on the ventilation systems of health-care settings.

Handling Editor: Xavier Querol

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106338.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adhikari U., Chabrelie A., Weir M., Boehnke K., McKenzie E., Ikner L., Wang M., Wang Q., Young K., Haas C.N., Rose J., Mitchell J. A case study evaluating the risk of infection from Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in a hospital setting through bioaerosols. Risk Anal. 2019;39(12):2608–2624. doi: 10.1111/risa.13389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIST Research Center for Chemical Risk Management, 2007. Inhalation rates. In Japanese Exposure Factors Handbook p.1 Available from: https://unit.aist.go.jp/riss/crm/exposurefactors/documents/factor/body/breathing_rate.pdf. accessed on August 12, 2020.

- Alford, R.H., Kasel, J.A., Gerone, .P.J, Knight, V., 1966. Human influenza resulting from aerosol inhalation. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 122, 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ali S., Noreen S., Farooq I., Bugshan A., Vohra F. Risk assessment of healthcare workers at the frontline against COVID-19. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020;36:S99–S103. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E.L., Turnham P., Griffin J.R., Clarke C.C. Consideration of the aerosol transmission for COVID-19 and public health. Risk Anal. 2020;40:902–907. doi: 10.1111/risa.13500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K., Uchiyama I., Okumura J. Assessing the risk of Legionnaires’ disease: The inhalation exposure model and the estimated risk in residential bathrooms. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013;65:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K., Kagi N., Kim H., Hayashi M. Impact of climate and ambient air pollution on the epidemic growth during COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Environ. Res. 2020;110042 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L., Gao H., Deng W., Lv Q., Yu H., Liu M., Yu P., Liu J., Qu Y., Gong S., Lin K., Qi F., Xu Y., Li F., Xiao C., Xue J., Song Z., Xiang Z., Wang G., Wang S., Liu X., Zhao W., Han Y., Wei Q., Qin C. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 via close contact and respiratory droplets among hACE2 mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;jiaa281 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch C.T., Lloyd-Smith J.O., Coffee M.P., Galvani A.P. Dynamically modeling SARS and other newly emerging respiratory illnesses: past, present, and future. Epidemiol. (Cambridge. 2005;Mass) 16:791–801. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181633.80269.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean B., Moore B.M., Sterner B., Peterson L.R., Gerding D.N., Balfour H.H., Jr. Survival of influenza viruses on environmental surfaces. J. Infect. Dis. 1982;146(1):47–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno G., Stabile L., Morawska L. Estimation of airborne viral emission: Quanta emission rate of SARS-CoV-2 for infection risk assessment. Environ. Int. 2020;141 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, R.M., Midgley, C.M., Dratch, A., Fenstersheib, M., Haupt, T., Holshue, M., et al., Active monitoring of persons exposed to patients with confirmed COVID-19 — United States, January–February 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 245–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Canova V., Lederer Schläpfer H., Piso R.J., Droll A., Fenner L., Hoffmann T., Hoffmann M. Transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 to healthcare workers -observational results of a primary care hospital contact tracing. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020;150 doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli M., Berretta M., Rullo E.V., Nunnari G., Cacopardo B. Differences and similarities between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-CoronaVirus (CoV) and SARS-CoV-2. Would a rose by another name smell as sweet? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:2781–2783. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]